Abstract

This paper proposes a novel control strategy for stand-alone doubly fed induction generator (DFIG)-based wind energy systems by integrating fractional-order operators into a fuzzy logic control (FLC) framework. Conventional FLC approaches typically use integer-order operators, which may restrict the system’s adaptability and dynamic performance. In this work, the standard integral and derivative components are replaced with fractional-order counterparts, resulting in a fractional-order fuzzy logic (FOFL) controller with a more flexible and tunable control architecture. This enhancement enables finer adjustment of the system response and improved robustness against external disturbances. The FOFL controller is applied within a direct voltage control (DVC) scheme to control the stator voltage and frequency. The performance of the proposed FOFL-DVC strategy is validated through simulation in MATLAB/Simulink and real-time experimental testing using a dSPACE-1104 platform. Results demonstrate that the FOFL-DVC strategy achieves high performance under both steady-state and transient conditions, ensuring stable operation under various wind speed and load disturbance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, considerable research and industrial efforts have been directed toward enhancing the performance, reliability, and integration of wind energy systems within modern power grids. Grid-connected wind turbines now operate under increasingly complex and dynamic conditions, including high wind variability, changing load demands, and strict grid code requirements1,2. To address these challenges, a wide range of intelligent control strategies and optimization frameworks have been developed. For example, a two-stage performance evaluation model was employed to assess the relative operational efficiency of wind power plants in India’s electricity sector, providing insights into performance benchmarking and regulatory planning3. Additionally, nature-inspired metaheuristic algorithms such as bacterial foraging optimization (BFOA)4 and whale optimization algorithm (WOA)5 have been successfully applied to tune controllers that suppress subsynchronous torsional oscillations in series-compensated wind farms, thereby improving system stability and reliability. Complementing these advancements6, hybrid renewable energy configurations, particularly wind, PV systems, have been proposed as flexible static compensators capable of supporting multimachine power systems during disturbances7. These intelligent hybrid systems improve overall voltage stability and enhance dynamic response by leveraging the complementary characteristics of different renewable sources8. Collectively, these developments highlight the critical importance of advanced control and optimization techniques in maximizing the reliability, stability, and grid compatibility of wind energy conversion systems (WECSs)8.

Despite this progress in grid-connected applications9,10,11, there is a growing need to explore the autonomous capabilities of wind energy systems, particularly in off-grid and isolated contexts. Wind generators must also be capable of delivering stable power to local loads during grid outages or in remote areas without access to centralized electricity infrastructure12,13. This is especially important in rural electrification initiatives and microgrid developments, where wind energy can serve as a standalone solution for decentralized power generation14. In such configurations, maintaining constant voltage and frequency at the stator terminals becomes a challenging yet essential requirement, particularly under fluctuating wind conditions and variable load profiles15,16. These operational demands have motivated increasing research into standalone wind energy systems, where control strategies must adapt in real-time to ensure robust and reliable performance without grid support.

Although permanent magnet synchronous generators (PMSGs) have gained widespread adoption in modern wind turbine systems, particularly in offshore, doubly-fed induction generators (DFIGs) remain the predominant choice for onshore wind farms, accounting for over 58% of the global onshore wind capacity17. This continued preference is largely attributed to the DFIG’s use of partial-scale converters, which process only 25–30% of the total generator power12,18. This configuration significantly reduces capital costs, minimizes switching losses, and simplifies power electronics design. Moreover, a key technical advantage of the DFIG topology is its ability to operate within a variable-speed range of ± 30% around synchronous speed13, enhancing energy capture efficiency under varying wind conditions while maintaining a compact and cost-effective system architecture.

Most control strategies used to supervise DFIGs are primarily based on field-oriented control (FOC) or direct voltage control (DVC) schemes19,20. DVC is known for its easy structure, and less parameter reliance, which has attracted a wide range of academic and industrial communities. This conventional approach employ proportional–integral (PI) controllers, however, due to their fixed parameters, linear PI controllers may not satisfy control needs when confronted with parameter uncertainty and/or external perturbations16. Moreover, in20, DVC was employed to control the stand-alone DFIG, where the findings demonstrated that this strategy exhibits drawbacks in the form of torque and power ripples, as well as poor current quality, which is undesirable.

Nonlinear control techniques have been suggested as effective ways to manage electric machines, with one of their key advantages being their long-term reliability21. In the literature, several nonlinear control strategies for standalone DFIGs are provided, such as backstepping control22, first or second sliding mode control (SMC)23,24, controllers based on H∞ theory25, and passivity-based control26. These approaches typically outperform linear strategies in terms of minimizing torque ripples and improving current quality21. However, the growing complexity of these systems creates challenges that result in higher costs and more difficult maintenance. Specifically, backstepping control in fusion processes depends heavily on the machine’s mathematical model, which presents certain limitations22.

In recent years, fuzzy control technique has been effectively applied in several engineering fields, including control of motor drives27, active power filter28, photovoltaic systems29, robotic navigation30, smart grids31, and so on. Fuzzy logic is well-regarded for its durability, effectiveness, and its ability to simplify the process by avoiding complex mathematical models. Using straightforward IF–THEN rules that reflect human reasoning, it excels in handling the nonlinearities and uncertainties typically found in control systems32. Studies have indicated that fuzzy logic controllers (FLCs) are more effective than conventional methods27,33,34. However, despite these advantages, classical FLCs also present several challenges and limitations in electrical control applications. They rely heavily on human expertise, which may be incomplete compared to systematic mathematical approaches32. Additionally, the absence of a general theoretical framework defining stability and robustness, due to the lack of a precise mathematical model, limits their applicability in complex systems29,32. FLCs can also suffer from inconsistencies in rule definitions, leading to contradictory decision-making. Furthermore, in high-dimensional and complex processes, the fuzzification and defuzzification stages can introduce computational delays, affecting real-time performance34. To address these drawbacks and enhance system accuracy and robustness, researchers have explored hybrid approaches that combine fuzzy logic with other techniques such as neural networks35, genetic algorithms36,37, sliding mode control38, and conventional control strategies39. In this work, we propose and validate a combination of fractional theory with fuzzy logic for DFIG-based stand-alone wind systems. This hybrid approach enhances adaptability, stability, and overall performance, mitigating the inherent limitations of classical FLCs. While fractional-order fuzzy logic controllers (FO-FLCs) have been investigated in several renewable energy contexts, particularly in photovoltaic systems, motor drives, and grid-tied wind applications, they remain largely unexplored in the domain of stand-alone DFIG-based wind energy systems. Most existing studies emphasize either simulation-based validation or grid-connected operation, often overlooking the control challenges introduced by the absence of grid support, such as maintaining voltage and frequency stability under rapid wind and load fluctuations. This work distinguishes itself by applying a fractional-order fuzzy logic-based direct voltage control (FOFL-DVC) strategy specifically tailored for stand-alone DFIG configurations, achieving robust stator voltage regulation without relying on grid synchronization. Unlike previous FO-FLC applications, the proposed controller is implemented and experimentally validated in real time using a dSPACE 1104 platform. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is one of the first real-time FO-FLC implementations in a wind energy context, filling a notable gap in the literature.

Fractional calculus known for its robustness, ease of implementation, and capacity to greatly enhance the dynamic response of systems compared to conventional methods39. This method has demonstrated remarkable efficacy in theoretical and practical contexts, particularly in the design of advanced control systems, owing to the flexibility provided by the fractional operator40. Its use has been effective in a number of technical domains41,42,43. For example, recent research has shown that fractional order calculus integration can improve the efficiency of conventional controllers. A PI controller was optimized in44 for the control of asynchronous generators using the fractional-order method. In comparison to the FOC approach, the simulation findings showed a decrease in torque ripples, a drop in total harmonic distortion (THD), and an increase in the system durability. These outcomes confirm the aspect of fractional calculus in enhancing the control system properties, making them more efficient and performing better.

This study introduces and experimentally validates an advanced control strategy, fractional-order fuzzy logic direct voltage control (FOFL-DVC), designed for stand-alone DFIG-based wind energy systems. By combining the flexibility of fuzzy logic with the enhanced tuning capabilities of fractional-order calculus, the FOFL-DVC approach achieves robust voltage and frequency regulation across a wide range of operating conditions. Real-time implementation on a 3-kW DFIG using a dSPACE 1104 platform confirms the practical viability of the method. The results demonstrate that the FOFL-DVC scheme delivers superior performance in both steady-state and dynamic conditions, particularly under fluctuating wind and load scenarios.

This paper is organized into six main sections. “WECS Configuration and Modeling” section describes the configuration and modeling of the stand-alone DFIG-based WECS. “Design of the proposed FOFL controller” section introduces the proposed fractional-order fuzzy logic (FOFL) controller, including its design and implementation. “Rotor side converter: proposed DVC based on FOFL controller” section details the application of the proposed strategy for direct voltage control (DVC) of the Rotor Side Converter. “Simulation and experimental results” section presents simulation and experimental results validating the proposed control scheme. Finally, “Conclusion” section concludes the paper with key findings.

WECS configuration and modeling

Stand-alone DFIG configuration

In wind energy conversion systems (WECS), there are two principal stator connection schemes in DFIG-based systems. The first is the grid-connected configuration, where the stator is connected to the grid, requiring synchronization between the stator and grid45. The second is the stand-alone configuration, where the stator is directly connected to the load, forming a micro-grid13,46. This topology eliminates the need for synchronization between the stator and load, and the DFIG generates power based on consumer demand without operating under maximum power point tracking (MPPT) conditions.

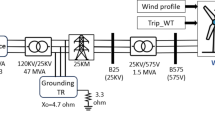

Figure 1 illustrates the proposed configuration for a stand-alone WECS based on a DFIG. The system includes a back-to-back converter with two-level IGBT-based voltage-fed converters: the rotor side converter (RSC) and the grid side converter (GSC). The primary objective of the RSC control in stand-alone operation is to keep the stator voltage and frequency constant, independent of variations in load and wind speed. The GSC’s role is to stabilize the DC link voltage at a constant value, and it is typically controlled by a voltage control (VC) strategy. Depending on the rotor speed relative to the synchronous speed (1500 rpm for a 4-pole machine at 50 Hz), the DFIG operates in different modes. When the rotor speed is below synchronous speed, the slip is positive (s > 0), indicating sub-synchronous operation, and the rotor absorbs power via the back-to-back converter. Conversely, when the rotor speed exceeds synchronous speed, the slip becomes negative (s < 0), representing super-synchronous operation, during which the rotor injects power back through the converter.

Wind turbine mathematical model

The power input to the wind turbine can be defined as47,48:

where ρ denotes air density, Sw is the swept area of the turbine blades, and v refers to the wind speed.

The wind turbine’s mechanical power output (illustrated schematically in Fig. 2) can be described by the following expression:

here the power coefficient (\({C}_{p}\)), which indicates the efficiency of the wind turbine’s energy conversion, is a nonlinear function of the tip speed ratio (TSR or λ) and blade pitch angle β. G represents the gearbox ratio.

The tip speed ratio (λ) is defined as the ratio between the rotational speed of the wind turbine blades and the wind speed. It is calculated as follows:

Here, R denotes the blade radius, and \({\Omega }_{t}\) represents the angular speed of the turbine. The power coefficient \({C}_{p}\) (λ, β) can be described using the following expression47,48:

Equation 4 captures the key aerodynamic effects of tip speed ratio and pitch angle while maintaining a balance between modeling accuracy and computational simplicity. The power coefficient curve \({C}_{p}(\lambda , \beta )\) was plotted in MATLAB/Simulink for various pitch angles (\(\beta^\circ\)), as shown in Fig. 3.

DFIG dynamic model

The dynamical model of the DFIG can be expressed using the following state equations in the dq synchronous reference frame13, with the d-axis aligned with the stator flux vector.

Stator and rotor voltages in d-q frame:

Stator and rotor fluxes in d-q frame:

The expression for the electromagnetic torque is:

The associated dynamic equation is:

where \({R}_{s}\), \({R}_{r}\), \({L}_{s}\) and \({L}_{r}\) denote the stator and rotor resistances and inductances, respectively, and \({L}_{m}\) represents the mutual inductance. The terms \({V}_{sd}\), \({V}_{sq}\), \({V}_{rd}\), \({V}_{rq}\), \({i}_{sd}\), \({i}_{sq}\), \({i}_{rd}\), \({i}_{rq}\), \({\varphi }_{sd}\), \({\varphi }_{sq}\), \({\varphi }_{rd}\) and \({\varphi }_{rq}\) correspond to the d- and q-axis components of stator and rotor voltages, currents, and magnetic fluxes, respectively.

The torques \({T}_{em}\), \({T}_{r}\), \({T}_{vis}\), \({T}_{aero}\) and \({T}_{g}\) represent the electromagnetic, load, viscous friction, aerodynamic, and gearbox torques. The inertias \({J}_{g}\), \({J}_{t}\) and \({J}\) refer to the generator, turbine, and total system inertia, respectively. \({\Omega }_{mec}\) is the mechanical speed, \(f\) is the friction coefficient, and \(G\) is the gain of gearbox. \(p\) is the number of pole pairs, ωs, ωm, and ωr are, respectively, the pulsation of the stator, the rotor and slip (\({\omega }_{r}={\omega }_{s}-{\omega }_{m})\).

Grid side converter (GSC): vector control

A vector control (VC) strategy is adopted for GSC, as shown in Fig. 4, to maintain the DC-link voltage at a constant level and ensure efficient power exchange between the RSC and the GSC. The VC method aligns the control frame with the grid voltage using a d–q transformation, enabling independent control of active and reactive power49,50.

The rectified current from the GSC is given by:

where \({S}_{11},{S}_{12}\) and \({S}_{13}\) are the switching states of the rectifier, and \({I}_{ga},{I}_{gb}\) and \({I}_{gc}\) are the network phase currents.

The switching signals are generated using a two-level hysteresis current controller (Fig. 4), which compares the measured grid currents \({I}_{gabc}\) with their corresponding reference values \({I}_{gabc\_ref}\) A hysteresis band of Δi = ± 0.01 A is selected to achieve a suitable trade-off between switching frequency and current ripple.

The capacitor’s DC voltage is determined by:

The DC-link voltage reference is given by:

Here \({I}_{d{c}_{-}GSC}\) and \({I}_{d{c}_{-}RSC}\) indicate the DC currents flowing to or from the GSC and RSC. A DC capacitor is implemented to suppress voltage oscillations and stabilize the DC-link voltage.

To regulate the DC-link voltage via the GSC, a PI controller is designed using the pole placement technique based on a first-order model of the capacitor dynamics, approximated as \(\left(s\right)=\frac{1}{C.s}\) . The controller gains are chosen to achieve a critically damped second-order closed-loop response with a desired natural frequency of \(\omega =200rad/s\). The proportional and integral gains are derived from the standard second-order characteristic equation \({C}^{2} \cdot s+{K}_{p} \cdot s+{K}_{i}\) and are given:

where ζ is the damping ratio, ω the desired natural frequency, and C the DC-link capacitance. This approach ensures a stable and fast voltage regulation without excessive overshoot.

Design of the proposed FOFL controller

Fractional-order (FO) concepts

Fractional calculus generalizes classical differentiation and integration to non-integer (fractional) orders. The fundamental operator \({}_{\alpha }{}{D}_{t}^{\lambda }\) of order \(\lambda \in \mathcal{R}\), defined over the interval [\(\alpha ,t\)], is denoted by51,52:

One of the most widely used definition of fractional calculus in control applications is the Grunwald–Letnikov formulation53. The definition of λ-order calculus for a continuous function \(f\left(t\right)\) can be described as follows:

where \(\left(\begin{array}{c}\lambda \\ j\end{array}\right)=\frac{\Gamma (\lambda +1)}{\Gamma \left(j+1\right) \cdot \Gamma (\lambda -j+1)}\) and Γ is the gamma function.

The coefficient \({{w}_{j}}^{\lambda }\) can be calculated more simply using the following recurrence formula39,53:

Equation (13) unifies fractional differential (when \(\lambda\)>0) and integral operations (when \(\lambda\)<0). The rounding operation \(\left[\frac{t-\alpha }{h}\right]\) ensures proper discretization, and h is the time step size.

Assuming zero initial conditions and the initial time t = 0, the Laplace transform of a fractional derivative or integral with constant coefficients can be represented as \(:\)

where s is the Laplace variable and \(F\left(s\right)\) is the Laplace transform of \(f\left(t\right)\).

Structure of the proposed FOFL controller

In this study, a robust and high-performance control strategy is proposed by integrating fractional calculus into a fuzzy logic controller. While conventional FLC schemes33 rely on integer-order integration and differentiation, the proposed fractional-order fuzzy logic (FOFL) controller introduces fractional operators \({}_{0}{}{D}_{t}^{{\varvec{\mu}}}\) and \({}_{0}{}{D}_{t}^{-\lambda }\) in the derivative and integrative paths, respectively, as represented in Fig. 5.

The FOFL controller receives two inputs: the normalized error \(e(t)\) and its fractional derivative \({}_{0}{}{D}_{t}^{\mu }e(t)\). These are processed by a fuzzy inference system (FIS), and the resulting control signal is scaled and fractionally integrated to produce the final output \(u\_ref\left(t\right)\). Input scaling factors GE and GCE normalize the inputs to ensure that are compatible with the universe of discourse defined by the membership functions, resulting in normalized variables E and \(\dot{E}\). An output gain \({G}_{CU}\) adjusts the intermediate fuzzy output before integration to maintain appropriate control amplitude.

The time-domain expression of the controller can be described by the following equation:

The parameters λ and µ are the integral-order operator and the differential-order operator, respectively. The values of λ and μ can calculated with optimization algorithm. In this study, are chosen manually tuned (between 0 and 1) based on desired system response.

The parameters λ and μ provide additional degrees of freedom compared to classical FLCs, allowing a more refined control strategy. The fractional differentiation order (μ) enhances sensitivity to system dynamics, enabling faster reaction to disturbances. The fractional integration order (λ) influences the memory effect, allowing a smoother control action by accumulating past information.

Figure 6 shows a λ-µ plane of the suggested FOFL controller. For λ = 1 and µ = 1, the controller is simplified to a traditional integer-order fuzzy logic controller. However, if λ and µ are chosen arbitrarily, then FOFL controller will cover the entire plane, offering a more flexible control strategy tailored to system requirements.

Fractional-order operator implementation

Fractional-order (FO) systems are characterized by their infinite-dimensional nature, which poses a significant challenge for real-time implementation in digital control systems. To make fractional operators practically usable, numerical approximation techniques must be employed. In this work, the Oustaloup’s recursive approximation (ORA) method is used to approximate both the fractional integral and fractional derivative operators. ORA effectively models the FO operator over a specified frequency band using a high-order rational transfer function53.

The approximation of the fractional-order operator \({s}^{\lambda }\) over a frequency band [\({\omega }_{b}{,\omega }_{h}\)] is given by:

where, s is the Laplace variable. \({\widehat{s}}_{\left[{\omega }_{b},{\omega }_{h}\right]}^{\lambda }\) denotes the approximated version of \({s}^{\lambda }\) over a finite frequency band [\({\omega }_{b}{,\omega }_{h}\)]. The parameters \({\omega }_{k}\), and \(\omega_{k}^{\prime }\) are the poles and zeros of the approximation filter, \(K\) is the gain and N is the filter order. These are computed using:

The FOFL controller can thus be expressed in the frequency domain as:

where \(e\left(\text{s}\right)\) and \(u\_ref\left(s\right)\) are the error and output signals in the Laplace domain. The terms \({\widehat{s}}_{\left[{\omega }_{b},{\omega }_{h}\right]}^{-\lambda }\) and \({\widehat{s}}_{\left[{\omega }_{b},{\omega }_{h}\right]}^{\mu }\) represent the rational approximations of the fractional integral and derivative operators, respectively. The implementation of the fractional-order operators is facilitated using the FOMCON (Fractional-Order Modeling and Control) toolbox in MATLAB, which offers a comprehensive framework for modeling, simulation, and real-time deployment of fractional-order control systems.

Rotor side converter: proposed DVC based on FOFL controller

Direct voltage control (DVC)

The RSC control is based on direct voltage control (DVC) to provide decoupling between the current control loops by aligning the stator flux with the d-axis16,54. This alignment simplifies the dynamics and control design of the DFIG system. By neglecting the rotor resistance and applying Eqs. (5 and 7), the system’s behavior is effectively described, as shown in:

That is:

Therefore, the reference stator voltage is defined as:

where the stator voltage magnitude of the DFIG is regulated by controlling the d-axis rotor current \({i}_{rd}\_ref\).

For a stand-alone DFIG system, the generator supplies power according to the load demand. Therefore, the q-axis rotor current reference \({i}_{rq}\_ref\) is derived from the active power component of the stator current \({i}_{sq}\) and can be calculated as:

To ensure that the stator output frequency fs remains fixed at the desired value of 50 Hz, it is necessary to synchronize the stator variables with the rotating dq reference frame. This is achieved using the Park transformation applied to the three-phase stator quantities.

The proposed fractional order fuzzy logic (FOFL) regulator applied in DVC

The proposed FOFL controller is implemented within a direct voltage control (DVC) scheme to regulate the stator voltage of the DFIG. Figure 7a illustrates the overall control architecture of the FOFL-DVC system, while Fig. 7b presents a detailed schematic of the FOFL controller integrated within the DVC loop. The FOFL block includes the fractional derivative operator (μ), fuzzy logic system, and fractional integrator (λ), enabling adaptive and robust voltage regulation.

In this control strategy, the FOFL controller generates the reference value of the rotor current \({i}_{rd}\_ref\), which is used to generate the control pulses for RSC. The control law in the Laplace domain is:

In this expression, \({e}_{{V}_{s}}(\text{s})={V}_{s}\_\text{ref}(\text{s})-{V}_{s}\_mes(s)\) represents the stator voltage error. This error signal \({e}_{{V}_{s}}(\text{s})\), along with its fractional derivative \({\widehat{s}}_{\left[{\omega }_{b},{\omega }_{h}\right]}^{\mu } \cdot {e}_{{V}_{s}}\left(\text{s}\right)\), serves as input to the fuzzy inference system (FIS). The fractional integral operator \({\widehat{s}}_{\left[{\omega }_{b},{\omega }_{h}\right]}^{-\lambda }\) and derivative \({\widehat{s}}_{\left[{\omega }_{b},{\omega }_{h}\right]}^{\upmu }\) are implemented using Oustaloup’s recursive approximation. In this study the frequency bands is chosen as \(\omega \in [{10}^{-3},{10}^{3}]\) rad/s, with a filter order of N = 5. This configuration ensures a balance between accuracy and computational efficiency.

The input and output scaling factors (\({G}_{E}\), \({G}_{CE}\) and \({G}_{CI}\)) were initially estimated based on normalized input–output behavior and later fine-tuned through simulation. The fractional orders \(\lambda\) and \(\mu\) were manually selected within the interval [0, 1] through simulation, and further optimized by observing the dynamic and steady-state performance under variable load and wind conditions. This provides a simple and accessible means to optimize controller performance without structural change.

For the fuzzy inference system (FIS), the control process is structured into three fundamental stages: fuzzification, rule-based inference, and defuzzification. In the fuzzification stage, triangular membership functions (MFs) are chosen for both inputs and outputs, with trapezoidal functions applied at the boundaries to address extreme values, as illustrated in Fig. 8. The rationale for this choice is based on several factors, such as triangular MFs are simple to implement, require minimal parameters, and offer robustness over a broad range of input and output values without compromising accuracy. Additionally, their interpretability enhances usability and understanding. The fuzzy rule base uses twenty-five control rules, as outlined in Table 1. In choosing these rules, a balance between the complexity of the controller and the predicted error is taken into account. In the defuzzification process, linguistic outputs from the inference mechanism are converted into numerical values using the center of gravity method34.

Simulation and experimental results

This section presents both simulation and experimental results to validate the proposed FOFL-DVC strategy. The simulation model was created using MATLAB/Simulink along with SimPowerSystems, while the experimental results were gathered from a test platform built in the laboratory. The DFIG characteristics used in both simulations and experiments are detailed in the supplementary tables (Tables S1 to S3). Figure 9 illustrates the experimental test bench, which comprises the following components: (1) PC with ControlDesk interface, used to monitor and manage the real-time control system via MATLAB/Simulink, (2) Tektronix TDS3014B 4-channel digital oscilloscope (100 MHz bandwidth, 1.25 GS/s sampling rate), (3) Emulated wind turbine using a 3 kW induction motor, (4) DFIG, rated at 3 kW, (5) Three-phase resistive load rated at 4 kW/400 V, (6) Three-phase power supply based on a three-phase autotransformer, (7) RSC using a two-level inverter used to perform the compensation, composed of six SEMIKRON SKM50GB123D IGBT modules (50 A, 1200 V) connected to a common DC-link capacitor, (8) Grid-side converter (GSC) using a similar two-level rectifier with six SKM50GB123D modules, (9) dSPACE 1104 DSP board, featuring 12-bit ADCs and 16-bit PWM resolution, (10) DC power Supply 5 V and 15 V adaptation circuit, (11) Voltage sensors (GW Instek GDP-025 differential probes), (12) Hall-effect current sensors (LEM PR30) for phase current measurement, offering approximately 100 kHz bandwidth, 66 mV/A sensitivity, and approximately 10 mA resolution when interfaced with the dSPACE ADCs, (13) Analog current sensors, (14) Signal adaptation circuit to convert control signals from 5 to 15 V for compatibility with IGBT gate drivers, (15) Manual switch for operational control, and (16) Encoder 1024 for speed measurement.

The control system was executed in real time on the dSPACE 1104 board, with a sampling time of 100 μs. The same sampling interval (Ts = 100 μs) was also used in the simulation environment to ensure consistent conditions for performance comparison. All tests were conducted under identical operating scenarios. This setup provides an effective environment for validating the proposed FOFL-DVC strategy in real time.

Test I: stator voltage reference variation

The proposed FOFL-DVC strategy was evaluated for its ability to track a step change in the reference stator voltage, which increased from 150 to 250 V, while the system operated under a fixed load condition of 30% rated power and fixed wind speed 1200 rpm. Figures 10 and 11 present the simulation and experimental results, respectively, of the proposed FOFL-DVC strategy in regulating the stator voltage during a step change in the reference voltage.

Figures 10a and b) and 11a–c illustrate the stator voltage amplitude Vs and its reference, as well as the direct-axis rotor current idr. Upon increasing the stator voltage reference, the output voltage Vs tracked the new setpoint with no overshoot or undershoot, and a fast settling time of 37 ms. This fast and accurate voltage tracking reflects the superior response time and dynamic stability of the proposed FOFL-based controller. Meanwhile, the d-axis rotor current idr smoothly increased from 7.2 to 12.3 A, showing excellent tracking of the control objective and highlighting the controller’s ability to respond rapidly to voltage reference variations without introducing oscillations.

Figures 10c and 11d and e depict the rotor current dynamics. The controller effectively adjusted the rotor excitation during the voltage step increased from 5 to a peak 8 A, maintaining stability and smooth transitions in current waveforms. The absence of overshoot and oscillations demonstrates the robustness and precision of the FOFL control law, even during sudden changes in the system reference.

Figure 11f–g show the evolution of stator active and reactive powers. As the voltage increased, the active power Ps rose from 150 to 410 W, confirming that the system effectively supplied the load demand. Importantly, the reactive power Qs remained stable at approximately 0 W. This result reflects the control system’s ability to manage reactive power effectively, prevent unwanted oscillations, and maintain a high power factor.

Figures 10d and 11h–i present the stator phase voltage waveforms. The stator voltage increased rapidly in response to the reference change while maintaining a purely sinusoidal waveform. The narrow tolerance band and low harmonic distortion confirm that the FOFL-DVC maintains high power quality and smooth waveform characteristics, even during abrupt dynamic events. The strong agreement between simulation and experimental data validates the efficacy and practical feasibility of the proposed controller for robust voltage regulation in stand-alone DFIG wind energy systems.

Test II: load variation

The performance of the proposed controller is evaluated under load changes. During this test, the DFIG operated at a fixed rotor speed of 1200 rpm, and the stator voltage reference was maintained at 150 V. The load was varied between 30 and 40% of the rated power to evaluate the system’s dynamic response. Figures 12 and 13 present the simulation and experimental results, respectively, of the proposed FOFL-DVC control strategy under conditions of sudden load variation. Figure 14 shows the THD results of the rotor current and stator voltage during load variation.

Figures 12a and b and 13a–c illustrate the stator voltage response Vs and the tracking behavior of the direct-axis rotor current ird. In both cases, the system achieved excellent voltage regulation with only a slight overshoot, followed by rapid disturbance rejection. This fast and precise tracking demonstrates the effectiveness of the FOFL controller in stabilizing the stator voltage under dynamic load conditions. The direct rotor current ird increased smoothly from 7.4 to 9 A, closely following its reference in both the simulation and experimental results, indicating accurate current regulation.

Figures 12c and 13d–e depict the rotor current dynamics in three phases. The current increased from 5 to a peak of approximately 6 A during the load step. The waveform transitions were smooth and well-regulated, with no overshoots or oscillations observed in either set of results.

Figures 12d and 13f–g present the evolution of stator active and reactive power. The active power increased from 150 to 220 W in accordance with the higher load demand, while the reactive power remained effectively stable at zero despite the increased load demand, with only minor ripples of ± 20 Var during the transition.

Figure 13h–i displays the stator current response. The stator current increased proportionally from 1 A to 1.5 A during the load transition, with minimal distortion.

Lastly, Figs. 12e and 13j–k show the frequency, electromagnetic torque and slip angle behavior. The stator frequency remained locked at 50 Hz. The torque rose from 2 to 5 Nm in both cases, with only minor ripples during the transition. The smooth torque profile and the absence of mechanical oscillations highlight the mechanical stability of the system and the effectiveness of the FOFL-DVC in minimizing stress during dynamic events.

Test III: wind speed variation

To further evaluate the stability of the proposed FOFL-DVC strategy, system responses were analyzed under varying wind speed conditions. Figures 15 and 16 present the simulation and experimental results of the proposed FOFL-DVC strategy under wind speed variation, evaluating its robustness and adaptability. Figure 16 presents the experimental results of the proposed FOFL-DVC strategy under wind speed variation, evaluating its robustness and adaptability. The rotor speed increased from 1350 RPM to 1650 rpm, while the stator voltage reference was kept constant at 150 V and the load fixed (30% of rated power).

Figures 15b and 16a,1 and 2 shows that the stator voltage amplitude remained stable during the speed transition, with the FOFL-DVC maintaining accurate regulation despite mechanical disturbances. This stability during speed variations demonstrates the control system’s effectiveness in managing both mechanical and electrical behaviors. The experimental results clearly align with the simulation outcomes, demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed control method under wind speed variations. Figure 15c and 16b,1 and 2 confirms that the stator voltage waveform remained sinusoidal and unaffected by speed variation, highlighting the control scheme’s ability to preserve voltage quality.

Figures 15d and 16c,1 and 2 present the rotor current behavior. The measured rotor current ira_mes aligned perfectly with the reference current ira_ref. A phase reversal was observed due to the transition from sub-synchronous to super-synchronous operation. The current tracking was precise, with excellent transient response, demonstrating the robustness of the FOFL-DVC under dynamic conditions. The synchronization between the actual and reference currents highlights the control strategy’s precise tracking and adaptive capabilities, ensuring smooth torque and power delivery despite variations in speed.

Figure 16d and e show that the stator active power remained constant, as expected under a fixed-load condition in a stand-alone setup. Both parameters exhibited minor fluctuations but remained stable, with active power stabilized at 500 W and reactive power at 0VAR. The slip angle reversed direction during the transition to super-synchronous mode and the stator frequency remained perfectly stable at 50 Hz.

Overall, the results validate the effectiveness of the FOFL-DVC control strategy across various operating conditions. Its capability to maintain accurate voltage regulation and ensure stable current control with minimal ripple confirms the robustness of the proposed method. Furthermore, it consistently demonstrates faster dynamic responses and lower steady-state errors. These findings underscore the potential of the control scheme to enhance power quality, making it particularly well-suited for stand-alone wind energy applications.

Performance comparison

Table 2 provides a brief comparison of control strategies in stand-alone modes based on experimental results. Several criteria have been considered to highlight the advantages and disadvantages of each control method. For certain performance indicators marked with (/), the corresponding numerical data were unfortunately unavailable.

Conclusion

This paper introduced and experimentally validated a fractional-order fuzzy logic direct voltage control (FOFL-DVC) technique for stand-alone DFIGs supplying local AC loads. The proposed control approach combines fuzzy logic, which provides adaptability to system variations, with fractional-order control, which enhances precision and dynamic performance. This combination allows the system to respond effectively to changes in load and wind speed without requiring an exact mathematical model. The FOFL-DVC was tested through both simulations and real-time experiments on a 3 kW DFIG prototype, confirming its ability to maintain stable operation under different conditions. The controller successfully tracked voltage reference changes without overshoot or undershoot, ensuring precise voltage regulation. It also maintained a stable stator voltage at 150 V during load variations, even when the rotor speed fluctuated. Additionally, under wind speed changes, the stator voltage remained steady as the rotor speed varied. Expectedly, the experimental results were similar to the simulations, validating the proposed control strategy’s effectiveness in real-world conditions. These findings demonstrate the FOFL-DVC’s robustness in ensuring voltage stability, minimizing harmonic distortion, and effectively regulating power delivery. However, the FOFL controller does have some limitations. The tuning of fractional-order parameters introduces additional complexity and computation compared to conventional controllers. Future work should focus on real-time adaptive tuning methods, long-term stability assessments, and the extension of this approach to grid-connected systems to further enhance its applicability.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Yousefzadeh, M. & Ahmadi Kamarposhti, M. Wind energy conversion systems: A review on aerodynamic, electrical and control aspects, recent trends, comparisons and insights. In Energy and Environmental Aspects of Emerging Technologies for Smart Grid (ed. Salkuti, S. R.) (Springer, 2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-18389-8_2.

Alex. Global Wind Report 2024. Global Wind Energy Council https://gwec.net/global-wind-report-2024/ (2024).

Sağlam, Ü. A two-stage data envelopment analysis model for efficiency assessments of 39 state’s wind power in the United States. Energy Convers. Manag. 146, 52–67 (2017).

Bakir, H., Merabet, A., Dhar, R. K. & Kulaksiz, A. A. Bacteria foraging optimisation algorithm based optimal control for doubly-fed induction generator wind energy system. IET Renew. Power Gener. 14, 1850–1859 (2020).

Kumar, R., Singh, R., Ashfaq, H., Singh, S. K. & Badoni, M. Power system stability enhancement by damping and control of Sub-synchronous torsional oscillations using Whale optimization algorithm based Type-2 wind turbines. ISA Trans. 108, 240–256 (2021).

Chaudhuri, A., Datta, R., Kumar, M. P., Davim, J. P. & Pramanik, S. Energy conversion strategies for wind energy system: Electrical mechanical and Material Aspects. Materials 15, 1232 (2022).

Kumar, R. et al. An intelligent Hybrid Wind–PV farm as a static compensator for overall stability and control of multimachine power system. ISA Trans. 123, 286–302 (2022).

Wang, L., Vo, Q.-S. & Prokhorov, A. V. Stability improvement of a multimachine power system connected with a large-scale hybrid wind-photovoltaic farm using a supercapacitor. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 54, 50–60 (2018).

Benamor, A., Benchouia, M. T., Srairi, K. & Benbouzid, M. E. H. A new rooted tree optimization algorithm for indirect power control of wind turbine based on a doubly-fed induction generator. ISA Trans. 88, 296–306 (2019).

Alruwaili, O. & Mohamed, M. Performance improvement of rotor current controller in doubly fed induction generation wind turbine with artificial intelligence methods. Energy Rep. 11, 2236–2254 (2024).

Liu, G., Liu, J. & Liu, A. A two-stage subsynchronous oscillation assessment method for DFIG-based wind farm grid-connected system. Sci. Rep. 14, 22290 (2024).

Chabani, M. S., Benchouia, M. T., Golea, A. & Becherif, M. Finite-state predictive current control of a standalone DFIG-based wind power generation systems: Simulation and experimental analysis. J. Control Autom. Electr. Syst. 32, 1332–1343 (2021).

Rostami, M., Madani, S. M. & Ademi, S. Sensorless closed-loop voltage and frequency control of stand-alone DFIGs introducing direct flux-vector control. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 67, 6078–6088 (2020).

Akbar, F., Syamsuddin, S., Andonal, N. & Nazir, R. Operation simulation of doubly fed induction generator (DFIG) as stand alone generator. In 2019 IEEE Conference on Energy Conversion (CENCON) 47–52 https://doi.org/10.1109/CENCON47160.2019.8974678. (2019).

Chen, W.-L. & Hsu, Y.-Y. Experimental evaluation of an isolated induction generator with voltage and frequency control. In International Symposium on Power Electronics, Electrical Drives, Automation and Motion, 2006. SPEEDAM 2006. 497–502 https://doi.org/10.1109/SPEEDAM.2006.1649823. (2006).

Touaiti, B., Azza, H. ben & Jemli, M. Control scheme for stand-alone DFIG feeding an isolated load. In 2019 10th International Renewable Energy Congress (IREC) 1–6 https://doi.org/10.1109/IREC.2019.8754515. (2019).

Muyeen, S. M. Wind energy conversion systems (Springer, 2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-2201-2.

Justo, J. J., Mwasilu, F. & Jung, J.-W. Doubly-fed induction generator based wind turbines: A comprehensive review of fault ride-through strategies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 45, 447–467 (2015).

Jenkal, H., Bossoufi, B., Boulezhar, A., Lilane, A. & Hariss, S. Vector control of a doubly fed induction generator wind turbine. Mater. Today Proc. 30, 976–980 (2020).

Imtiyaz, T., Bakhsh, F. I. & Jain, A. Modelling and analysis of vector controlled doubly fed induction generator (DFIG). In Power Electronics and High Voltage in Smart Grid (eds Gupta, A. R. et al.) 255–268 (Springer, 2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-7393-1_21.

Chojaa, H. et al. Advanced control techniques for doubly-fed induction generators based wind energy conversion systems. In 2022 Global Energy Conference (GEC) 282–287 (IEEE, Batman, Turkey, 2022). https://doi.org/10.1109/GEC55014.2022.9987088.

Morawiec, M., Blecharz, K. & Lewicki, A. Sensorless rotor position estimation of doubly fed induction generator based on backstepping technique. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron 67, 5889–5899 (2020).

Barkia, A. et al. A comparative study of PI and Sliding mode controllers for autonomous wind energy conversion system based on DFIG. In 2016 17th International Conference on Sciences and Techniques of Automatic Control and Computer Engineering (STA) 612–617 https://doi.org/10.1109/STA.2016.7952039. (2016).

Guo, L., Wang, D., Peng, Z. & Diao, L. Improved super-twisting sliding mode control of a stand-alone DFIG-DC system with harmonic current suppression. IET Power Electron. 13, 1311–1320 (2020).

Belfedal, C. et al. Robust control of doubly fed induction generator for stand-alone applications. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 80, 230–239 (2010).

Wu, W. J. & Xue, H. Passivity-based control strategies of doubly fed induction wind power generator without speed sensors. Appl. Mech. Mater. 380–384, 3124–3128 (2013).

Manuel, N. L., İnanç, N. & Lüy, M. Control and performance analyses of a DC motor using optimized PIDs and fuzzy logic controller. Results Control Optim. 13, 100306 (2023).

Benchouia, M. T., Ghadbane, I., Golea, A., Srairi, K. & Benbouzid, M. E. H. Implementation of adaptive fuzzy logic and PI controllers to regulate the DC bus voltage of shunt active power filter. Appl. Soft Comput. 28, 125–131 (2015).

Bacha, M., Terki, A. & Bacha, M. Comparative study of real-time photovoltaic fault diagnosis using artificial intelligence: Fuzzy logic and neural network approaches. Energy Sources Part Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 46, 13536–13560 (2024).

Masmoudi, M. S., Krichen, N., Masmoudi, M. & Derbel, N. Fuzzy logic controllers design for omnidirectional mobile robot navigation. Appl. Soft Comput. 49, 901–919 (2016).

Baz, A., Logeshwaran, J., Natarajan, Y. & Patel, S. K. Deep fuzzy nets approach for energy efficiency optimization in smart grids. Appl. Soft Comput. 161, 111724 (2024).

Chabani, M. S. et al. Takagi-Sugeno fuzzy logic controller for DFIG operating in the stand-alone mode: Simulations and experimental investigation. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 48, 14605–14620 (2023).

Nethaji, G. & Kathirvelan, J. Performance comparison between PID and Fuzzy logic controllers for the hardware implementation of traditional high voltage DC-DC boost converter. Heliyon 10, e36750 (2024).

Bahgat, M., Ezzat, M., Attia, M. A., Mekhamer, S. F. & Elbehairy, N. M. Comparative analysis of PI and fuzzy logic controller for grid connected wind turbine under normal and fault conditions. Sci. Rep. 15, 1954 (2025).

Arifin, Md. S., Uddin, M. N. & Wang, W. Neuro-fuzzy adaptive direct torque and flux control of a grid-connected DFIG-WECS with improved dynamic performance. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 59, 7692–7700 (2023).

Elnaghi, B. E., Ismaiel, A. M., El Sayed Abdel-Kader, F., Abelwhab, M. N. & Mohammed, R. H. Validation of energy valley optimization for adaptive fuzzy logic controller of DFIG-based wind turbines. Sci. Rep. 15, 711 (2025).

Venkatanarayana, B. & Rosalina, K. M. A new MPPT mechanism based on multi-verse optimization algorithm tuned FLC for photovoltaic systems. Sci. Rep. 14, 28066 (2024).

Saihi, L. et al. Fuzzy-sliding mode control second order of wind turbine based on DFIG. In 2022 10th International Conference on Smart Grid (icSmartGrid) 296–300 https://doi.org/10.1109/icSmartGrid55722.2022.9848587. (2022).

Liu, D. et al. Fuzzy self-tuning fractional order PD permanent magnet synchronous motor speed control based on torque compensation. Sci. Rep. 15, 2141 (2025).

Benbouhenni, H. et al. Application of fractional-order synergetic-proportional integral controller based on PSO algorithm to improve the output power of the wind turbine power system. Sci. Rep. 14, 609 (2024).

Ekinci, S. et al. Optimized FOPID controller for steam condenser system in power plants using the sinh-cosh optimizer. Sci. Rep. 15, 6876 (2025).

Vijayakumar, S. & Sudhakar, N. Golden eagle optimized fractional-order PI controller design for a PFC SEPIC converter in EV charging. Sci. Rep. 14, 20954 (2024).

Mousavi, Y. & Alfi, A. A memetic algorithm applied to trajectory control by tuning of fractional order proportional-integral-derivative controllers. Appl. Soft Comput. 36, 599–617 (2015).

Karad, S. G. et al. Optimal design of fractional order vector controller using hardware-in-loop (HIL) and opal RT for wind energy system. IEEE Access 12, 35033–35047 (2024).

Dida, A., Merahi, F. & Mekhilef, S. New grid synchronization and power control scheme of doubly-fed induction generator based wind turbine system using fuzzy logic control. Comput. Electr. Eng. 84, 106647 (2020).

Mebkhouta, T. et al. Sensorless finite set predictive current control with MRAS estimation for optimized performance of standalone DFIG in wind energy systems. Results Eng. 24, 103622 (2024).

Phan, V.-T., Nguyen, D.-T., Trinh, Q.-N., Nguyen, C.-L. & Logenthiran, T. Harmonics rejection in stand-alone doubly-fed induction generators with nonlinear loads. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 31, 815–817 (2016).

Phan, V.-T. & Lee, H.-H. Stationary frame control scheme for a stand-alone doubly fed induction generator system with effective harmonic voltages rejection. IET Electr. Power Appl. 5, 697–707 (2011).

Abad, G., López, J., Rodríguez, M. A., Marroyo, L. & Iwanski, G. Doubly Fed Induction Machine: Modeling and Control for Wind Energy Generation (Wiley, 2011). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118104965.

Amrane, F., Francois, B. & Chaiba, A. Experimental investigation of efficient and simple wind-turbine based on DFIG-direct power control using LCL-filter for stand-alone mode. ISA Trans. 125, 631–664 (2022).

Marszałek, K., Domański, A. & Milik, A. Usage of fractional order PIλ Dμ controller as AQM algorithm. Sci. Rep. 13, 18537 (2023).

Jmal, A., Naifar, O., Ben Makhlouf, A., Derbel, N. & Hammami, M. A. A brief overview on fractional order systems in control theory. In Fractional Order Systems—Control Theory and Applications: Fundamentals and Applications (eds Naifar, O. & Ben Makhlouf, A.) 29–47 (Springer, 2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-71446-8_3.

Petráš, I. Fractional-Order Nonlinear Systems: Modeling, Analysis and Simulation (Springer, 2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-18101-6.

Amrane, F., Chaiba, A., Francois, B. & Babes, B. Experimental design of stand-alone field oriented control for WECS in variable speed DFIG-based on hysteresis current controller. In 2017 15th International Conference on Electrical Machines, Drives and Power Systems (ELMA) 304–308 https://doi.org/10.1109/ELMA.2017.7955453. (2017).

Zhang, Y., Hu, J. & Zhu, J. Three-vectors-based predictive direct power control of the doubly fed induction generator for wind energy applications. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 29, 3485–3500 (2014).

Misra, H., Gundavarapu, A. & Jain, A. K. Control scheme for DC voltage regulation of stand-alone DFIG-DC system. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 64, 2700–2708 (2017).

Marques, G. D. & Iacchetti, M. F. Sensorless frequency and voltage control in the stand-alone DFIG-DC system. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 64, 1949–1957 (2017).

Chabani, M. S., Benchouia, M. T., Golea, A., Abdealziz, A. Y. & Mossa, M. A. A new sensor-less voltage and frequency control of stand-alone DFIG based dead-beat direct-rotor flux control-experimental validation. ISA Trans. 158, 715–734 (2025).

Bouchafaa, F., Beriber, D. & Boucherit, M. S. Modeling and control of a gird connected PV generation system. In 18th Mediterranean Conference on Control and Automation, MED’10 315–320 https://doi.org/10.1109/MED.2010.5547687. (2010).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, F.B., M.A., A.A., and M.T.B.; methodology, F.B., M.A., K.A., M.T.B, M.B., and T.G.; software, F.B., K.A., M.T.B, M.B., B.M.A., and T.G.; validation, M.A., A.A., and B.M.A.; formal analysis, M.A., A.A., K.A., M.T.B., B.M.A., M.B, and T.G.; investigation, K.A., M.T.B., B.M.A., M.B., and T.G.; writing—original draft preparation, F.B., M.A., A.A., K.A., M.T.B., B.M.A, M.B., and T.G.; supervision, M.T.B., and T.G.; project administration, T.G.; funding acquisition, K.A., T.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Boucetta, F., Alturki, M., Albaker, A. et al. Robust direct voltage control of stand-alone DFIG wind systems using a fractional-order fuzzy logic approach. Sci Rep 15, 28762 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11910-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11910-1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Robust low complexity multisurface super twisting sliding mode control for DFIG systems

Scientific Reports (2025)