Abstract

Despite the impact of pregnancy and parity on the prevalence of metabolic diseases, there are limited epidemiologic data regarding the association between parity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). We examined the association between parity, parity number, and NAFLD risk in pre- and postmenopausal women using data representing the entire Korean population. This cohort included 28,003 women (13,145 premenopausal and 14,858 postmenopausal) from the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. NAFLD was defined by the hepatic steatosis index. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was used to calculate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The prevalence of NAFLD was 21.0% (15.3% in premenopausal women and 26.1% in postmenopausal women). In premenopausal women, parity increased the odds of NAFLD in the unadjusted model (OR 1.72, 95% CI 1.49–2.00), but after adjustment for potential confounders, including obesity, it exhibited a protective effect (OR 0.61, 95% CI 0.46–0.80). This finding was consistent when participants were divided into low parity (1–2 births) and high parity (3 or more births) groups (OR 0.59, 95% CI 0.45–0.79, and OR 0.64, 95% CI 0.47–0.87, respectively). In postmenopausal women, there was no significant statistical association between parity and NAFLD. These findings remained consistent across several sensitivity analyses excluding potential risk factors and in subgroup analyses. After adjusting for various confounding parameters, including obesity, parity was associated with a lower risk of NAFLD in premenopausal women. This suggests a protective effect of parity on NAFLD in premenopausal women, provided that appropriate body weight and other metabolic risk factors are maintained after delivery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common chronic liver disease, with an estimated prevalence of 38% worldwide, and is rapidly increasing alongside global obesity and sedentary lifestyle trends1. The incidence and prevalence of NAFLD have been rising in younger populations in recent years2. Since young adults with NAFLD have a longer life expectancy than older adults, they are at an increased risk of developing complications associated with NAFLD, such as liver cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and cardiovascular disease.

Reproductive factors, such as menstruation cycles, menopause status, parity, and breastfeeding, are known to be associated with NAFLD in women3,4. Although the biological mechanisms underlying these factors in NAFLD development are not fully understood, they suggest a close relationship between reproductive hormones, including estrogen, and NAFLD5. Few studies have examined the association between parity and NAFLD. A Multiethnic Cohort Study of 19,636 women aged 45 to 75 years found that parity was associated with increased odds of NAFLD6. However, most study participants (83%) were postmenopausal, and parity was categorized in a binary manner, without considering parity number. Another study from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey-III, including 3,502 women aged 19 to 49 years, found that women with NAFLD had higher odds of parity compared to controls, but the statistical significance disappeared after adjusting for confounding factors, including obesity7. These studies were mainly based on Western populations, whereas in Asians, a significant proportion of patients with NAFLD are not obese, with a prevalence rate of 5–45%8.

Given the limited epidemiological data on the association between parity and NAFLD risk and the potential confounding effects of menopausal status and other reproductive factors, a large-scale study effectively controlling for these confounding factors is needed. Therefore, in this study, we examined the impact of parity and parity number on NAFLD risk, stratified by menopausal status, using data from a nationwide population-based cohort.

Materials and methods

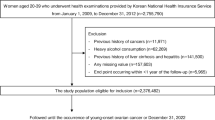

Study design and population

The Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) is a nationwide, population-based, cross-sectional observational study that represents the general Korean population. It includes data from health examinations along with anthropometric measurements, blood sampling, and questionnaires on lifestyle, behavior, and reproductive history. Details of the cohort have been previously described9.

We included women over 19 years of age who participated in KNHANES from 2010 to 2021 (n = 42,010). Among them, we excluded women with chronic liver disease (n = 1,683), heavy alcohol consumption (n = 3,085), malignancy (n = 2,004), current pregnancy and/or breastfeeding (n = 696), and missing data (n = 7,790). Finally, 28,003 women were eligible for analysis. This study was approved by the Ewha University Institutional Review Board in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (SEUMC2023-09–009).

Measurements of variables and definitions

Trained health interviewers conducted surveys to collect information on reproductive factors, including parity status, number of parities, breastfeeding status and duration, age at menarche, and age at menopause. Given that menopause significantly affects metabolic parameters and NAFLD, analyses were conducted separately based on menopausal status. Menopause was defined as a period of no menstruation for at least 12 months. Information on age, body mass index (BMI, calculated as weight (kg) divided by height squared (m2)), waist circumference (WC), systolic and diastolic blood pressure, household income, educational level, physical activity, smoking, alcohol consumption, and history of chronic liver disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia was also collected.

Participants underwent venous blood sampling after fasting for over 8 h. Samples were transported to a Central Testing Institute in Seoul, South Korea, following standardized procedures and were analyzed within 24 h. Laboratory data collected included triglycerides (TG), total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, glucose, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), HBsAg, and HCV antibody.

Chronic liver disease was defined by the presence of positive HBsAg or HCV antibodies in blood tests or a history of liver cirrhosis as reported in the medical history questionnaire. Heavy alcohol consumption was defined as consuming 20 g or more of alcohol per day. Type 2 diabetes mellitus was defined by a fasting glucose level of ≥ 126 mg/dL or a history of diabetes in the medical history questionnaire. Hypertension was defined by blood pressure ≥ 140/90 mmHg or a history of hypertension. Hyperlipidemia was defined by total cholesterol ≥ 240 mg/dL or a history of hyperlipidemia.

Definition of NAFLD

NAFLD was defined using the hepatic steatosis index (HSI), calculated with the following formula: 8 × AST/ALT + BMI (+ 2 if diabetes mellitus, + 2 if female), with HSI > 36.0 considered indicative of NAFLD10.

Statistical methods

Baseline characteristics of the study population are presented as mean ± SD for continuous variables and as numbers (%) for categorical variables. Participants were categorized into groups based on parity status (with or without parity) and, for those with parity, further divided into two groups: parity of 1–2 births and 3 or more births. Variable comparisons among groups were performed using Student’s t-test for two-group comparisons, analysis of variance (ANOVA) for three or more groups, and chi-square tests for categorical variables. When ANOVA indicated a significant difference among parity groups, post hoc pairwise comparisons were performed using the Tukey–Kramer method. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was conducted to evaluate the association between parity and/or parity number and NAFLD. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated, adjusting for age and WC in Model 1; household income, educational level, physical exercise, smoking, and alcohol consumption in Model 2; and systolic blood pressure, glucose, triglycerides, HDL cholesterol, age at menarche, and age at menopause (for postmenopausal women) in Model 3. All P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.4 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the study population according to menopausal status are shown in Table 1. Among premenopausal women, those with higher parity were generally older and had higher BMI, WC, systolic blood pressure, and diastolic blood pressure than those without parity. They also had a higher proportion of low household income and low educational attainment. Although a higher proportion of these women did not drink alcohol, there was no statistically significant difference in smoking rates. There were increasing trends in triglyceride, total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, glucose, AST, and ALT levels, and the prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia also increased with parity.

In postmenopausal women, there were no differences in BMI, systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure among the groups; however, there was a tendency for increased WC and a higher proportion of low educational attainment and non-smoking status as parity increased. There was no clear difference in levels of triglycerides, total cholesterol, glucose, AST, and ALT. However, the prevalence of hyperlipidemia decreased, and the prevalence of diabetes and hypertension was lowest in the 1–2 parity group, followed by the no-parity and 3 or more parity groups. Women with parity had a later age at menopause compared to those without parity. These baseline characteristics showed similar trends when stratified by parity (Supplementary Table 1).

In premenopausal women, we further analyzed baseline characteristics stratified by the combination of parity and NAFLD status. Women with parity and NAFLD were oldest, followed by those with parity without NAFLD no parity with NAFLD, and no parity without NAFLD. Waist circumference, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and levels of triglycerides, total cholesterol, and fasting glucose were highest in women with parity and NAFLD, followed by no parity with NAFLD, parity without NAFLD, and no parity without NAFLD (Supplementary Table 2).

Risk of NAFLD according to parity and parity number

Of the 28,003 women included in the analysis, 5,889 (21.0%) met the criteria for NAFLD (Table 2). In the premenopausal group, women with parity had higher odds of NAFLD compared to those without parity in an unadjusted model (OR 1.72, 95% CI 1.49–2.00). However, after adjusting for age, the odds decreased to 1.03 (95% CI 0.86–1.23), and after adjusting for WC, the odds significantly decreased (OR 0.63, 95% CI 0.48–0.83). This protective effect remained significant after adjusting for multiple variables, including household income, educational level, physical exercise, smoking, alcohol consumption, systolic blood pressure, glucose, TG, HDL cholesterol, and age at menarche (OR 0.61, 95% CI 0.46–0.80). The odds of NAFLD significantly decreased in both the 1–2 parity and 3 or more parity groups compared to those without parity after fully adjusting for confounding factors. In postmenopausal women, there was no statistically significant association between parity and NAFLD. A similar trend was observed when parity was categorized as 1, 2, and ≥ 3 (Supplementary Table 3).

Three sensitivity analyses were conducted to test the robustness of the results. First, we excluded women with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Second, we excluded women with hyperlipidemia. Third, we excluded women with cardiovascular disease. Forth, we excluded women who were underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2). Similar protective effects of parity on NAFLD odds were observed in premenopausal women after adjusting for multiple confounding factors (Supplementary Table 4).

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analysis was performed stratified by age, BMI, WC, systolic blood pressure, triglyceride levels, glucose levels, income, education, smoking, alcohol, age at menarche, and age at menopause. After full adjustment, there were no statistically significant interactions between subgroups in either premenopausal or postmenopausal women (Fig. 1).

Discussion

In this nationwide population-based cohort of 28,003 women, parity was negatively associated with NAFLD in premenopausal women. This protective effect persisted after adjusting for multiple variables, including obesity and other metabolic parameters, and remained even with an increase in parity number. The impact of parity on NAFLD did not vary according to age, obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, or hyperglycemic status. In postmenopausal women, a trend toward a negative association between parity and NAFLD was observed, but it did not reach statistical significance.

Few studies have investigated the association between parity and NAFLD. In the Multiethnic Cohort study of 19,363 women, parity was significantly associated with increased odds of NAFLD6. In contrast to our study, the participants were aged 45 to 75 years, mostly postmenopausal. The diagnosis of NAFLD was conducted using ICD-9 or ICD-10 codes, and parity was categorized into nulliparity and ever-parity groups, without consideration of the number of parities. We analyzed NAFLD risk by parity, stratified by premenopausal and postmenopausal status, as menopause critically impacts NAFLD and its severity11. Additionally, NAFLD diagnosis using only ICD codes may have low accuracy and miss undiagnosed cases, so we used the validated NAFLD index, HSI12. Consequently, although there was no statistical difference in postmenopausal women, parity showed a protective effect against NAFLD in premenopausal women. Another study from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey-III with 3,502 women aged 19 to 49 years found that women with NAFLD had higher odds of parity compared to controls, though the statistical significance disappeared after adjusting for confounding factors, including obesity7. This study differs from ours in that it used parity as the dependent variable in patients with chronic liver disease, including NAFLD, considering various confounding factors.

In this study, baseline characteristics showed that as parity or its number increased, women tended to be obese and had higher levels of glucose, triglycerides, cholesterol, AST, and ALT, as well as a higher prevalence of metabolic comorbidities. This is consistent with previous studies showing an association between parity and an increased risk of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes mellitus13,14. In a meta-analysis of 15 studies, the odds ratio for metabolic syndrome in parous versus nulliparous women was 1.31 (95% CI = 0.91–1.88)13. However, the relationship between parity and metabolic syndrome remains inconsistent, with some investigators questioning its strength15. For example, a Korean study initially observed a positive relationship between parity and metabolic syndrome, but this relationship was not maintained after adjusting for confounding factors, including age and BMI16. In our unadjusted model, women with parity showed higher odds of NAFLD compared to nulliparous women. However, after adjusting for age and WC, the results were reversed, and this inverse association remained significant after adjusting for additional confounders in premenopausal women. These findings suggest that the initial positive association may have been primarily attributable to confounding variables—particularly central obesity and socioeconomic status—which were more prevalent among women with parity group. When these factors were adequately controlled for, the direction of the association reversed, implying that parity itself may not be harmful, and could potentially have a beneficial role in NAFLD under healthy metabolic conditions.

Despite a trend towards a negative correlation, there were no statistically significant differences in NAFLD risk by parity in postmenopausal women. This may be due to the influence of complex factors acting over a longer period compared to premenopausal women, potentially diluting the protective effect of parity on NAFLD. Menopause is accompanied by significant hormonal changes and metabolic deterioration17, suggesting that the protective effect of parity against NAFLD may be overshadowed by menopausal changes.

The underlying mechanism linking parity and NAFLD is not fully understood. The liver is a major organ involved in regulating energy balance and homeostasis, and it interacts bidirectionally with the reproductive system5,18. Men and postmenopausal women show higher incidences of NAFLD/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) than premenopausal women, and studies support a potential protective role of estradiol in liver diseases19. Estrogen receptors (ERs) are expressed in hepatocytes, and the binding of ERα and 17β-Estradiol (E2) influences liver transcriptional regulators, such as nuclear factor erythroid-2-related factor (NrF2), fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21), and farnesoid X receptor (FXR), enhancing lipid metabolism and inhibiting lipogenesis and gluconeogenesis20,21,22. Experimental studies demonstrate estrogen’s protective effect on NAFLD development and progression. For instance, female mice with ERα knockdown exhibit hepatic TG accumulation, while mice with ERα overexpression show amelioration of hepatic steatosis through increased hepatic small heterodimer partner expression20. Estradiol treatment has improved insulin resistance and reduced hepatic fat accumulation by suppressing lipogenesis-related genes in obese female ob/ob mice23. G protein-coupled estrogen receptor 1 (GPER1), associated with metabolic diseases such as obesity and diabetes, is a membrane estrogen receptor. In an NAFLD/NASH mouse model, hepatocyte-specific GPER1 knockout exacerbated hepatic lipid accumulation, inflammation, fibrosis, and insulin resistance, while GPER1 activation mitigated these effects via the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) pathway24. Additionally, hepatic stellate cells incubated with estrogen showed reduced collagen synthesis and delayed liver fibrosis in an oxidative stress environment by suppressing NADH/NADPH oxidase activity, which generates reactive oxygen species, and by inactivating transforming growth factor (TGF)β1 transcription25.

During pregnancy, the placenta produces large amounts of hormones, including estrogen, to sustain pregnancy, causing metabolic changes to promote energy and nutrient storage26. It has been reported that 14–20% of women retain pregnancy-related weight gain postpartum, leading to potential health risks27. A recent meta-analysis of 18 studies found that higher gestational weight gain results in short- and long-term postpartum weight retention28. Weight gain during midlife is a significant predictor of metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. However, many women report challenges in losing postpartum weight in both the short- and long-term29. One cohort study found that excessive gestational weight gain resulted in long-term abdominal obesity, increasing the risk of cardiometabolic diseases in women 4–12 years postpartum30. Another study over 21 years reported that women with excessive pregnancy weight gain had an increased risk of diabetes later in life, likely mediated by postpartum weight retention29. Walter et al. demonstrated that higher total and first-trimester gestational weight gain were associated with higher systolic blood pressure and larger WC at 3 and 7 years postpartum31. A meta-analysis of 17 studies reported a positive association between parity and pre-pregnancy BMI, but postpartum weight retention findings were inconsistent32. While pregnancy results in a transient positive energy balance and weight gain, which can elevate long-term risks for metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes mellitus if not managed postpartum13,14, our results demonstrated that, after adjusting for mediating factors such as central obesity and metabolic dysregulation, parity was associated with a protective effect against NAFLD. This finding suggests that parity itself may mitigate the risk of NAFLD through hormonal changes and related metabolic effects. Therefore, managing postpartum weight gain and metabolic risk factors may be important for the prevention of NAFLD. Although several postpartum weight loss interventions have shown efficacy, most studies have focused on Western women; further validation is needed in diverse ethnic groups27.

A key strength of this study is its large sample size from a nationwide population-based database, reflecting the entire Korean population. Recognizing that menopause is a period of rapid changes in anthropometric and metabolic parameters in women, we analyzed data separately by premenopausal and postmenopausal status. Additionally, we extensively adjusted for confounding factors, including anthropometric, metabolic, and reproductive/gynecological parameters. However, the study has limitations. First, its cross-sectional design makes it challenging to assess causal relationships. Second, NAFLD was diagnosed by HSI, not a standard method such as liver biopsy or ultrasonography. Although these methods offer greater diagnostic accuracy for NAFLD, they are not feasible in large-scale epidemiological studies. Other NAFLD indices such as the fatty liver index (FLI) could not be used due to missing variables such as gamma-glutamyl transferase. Nevertheless, HSI has been validated as a reliable index for NAFLD in several large epidemiological studies4,12. Third, data on menstruation status, parity, and other gynecological factors were self-reported. Fourth, we could not confirm infertility in nulliparous women, such as polycystic ovary syndrome, which is associated with NAFLD and may have influenced our findings. Lastly, as the study was conducted on the Korean population, additional research is required to generalize findings to other ethnicities or countries.

In conclusion, parity was associated with a lower risk of NAFLD in Korean premenopausal women. This association was consistent across parity numbers and was independent of other risk factors, including obesity and other metabolic parameters. Since premenopausal women have a relatively long-life expectancy, the development of NAFLD during this period increases their exposure to liver-related complications and cardiometabolic diseases over time. It is thus crucial to identify risk or protective factors for NAFLD in this population. Further studies are warranted to clarify the underlying biological mechanisms and validate these results in other populations.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- ALT:

-

Alanine aminotransferase

- AMPK:

-

AMP-activated protein kinase

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- AST:

-

Aspartate aminotransferase

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- E2:

-

17β-Estradiol

- ER:

-

Estrogen receptor

- FGF21:

-

Fibroblast growth factor 21

- FXR:

-

Farnesoid X receptor

- GPER1:

-

G protein-coupled estrogen receptor 1

- HDL:

-

High-density lipoprotein

- HSI:

-

Hepatic steatosis index

- KNHANES:

-

Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- LDL:

-

Low-density lipoprotein

- NAFLD:

-

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- NASH:

-

Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

- NrF2:

-

Nuclear factor erythroid-2-related factor

- TG:

-

Triglycerides

- TGF:

-

Transforming growth factor

- WC:

-

Waist circumference

References

Younossi, Z. M. et al. The global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH): a systematic review. Hepatology 77, 1335–1347 (2023).

Paik, J. M. et al. Global burden of NAFLD and chronic liver disease among adolescents and young adults. Hepatology 75, 1204–1217 (2022).

Ajmera, V. H. et al. Longer lactation duration is associated with decreased prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in women. J. Hepatol. 70, 126–132 (2019).

Park, Y. et al. The association between breastfeeding and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in parous women: A nation-wide cohort study. Hepatology 74, 2988–2997 (2021).

Mahboobifard, F. et al. Estrogen as a key regulator of energy homeostasis and metabolic health. Biomed. Pharmacother. 156, 113808 (2022).

Wang, J. et al. Associations Between Reproductive and Hormone-Related Factors and Risk of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in a Multiethnic Population. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 19(1258–1266), e1251 (2021).

Golabi, P. et al. Association of parity in patients with chronic liver disease. Ann. Hepatol. 17, 1035–1041 (2018).

Eslam, M., Chen, F. & George, J. NAFLD in lean asians. Clin. Liver Dis (Hoboken) 16, 240–243 (2020).

Kweon, S. et al. Data resource profile: The Korea national health and nutrition examination survey (KNHANES). Int. J. Epidemiol. 43, 69–77 (2014).

Lee, J. H. et al. Hepatic steatosis index: a simple screening tool reflecting nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Dig. Liver Dis. 42, 503–508 (2010).

Yang, J. D. et al. Gender and menopause impact severity of fibrosis among patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology 59, 1406–1414 (2014).

Meffert, P. J. et al. Development, external validation, and comparative assessment of a new diagnostic score for hepatic steatosis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 109, 1404–1414 (2014).

Sun, M. H. et al. Parity and Metabolic Syndrome Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 15 Observational Studies With 62,095 Women. Front. Med. (Lausanne) 9, 926944 (2022).

Guo, P., Zhou, Q., Ren, L., Chen, Y. & Hui, Y. Higher parity is associated with increased risk of Type 2 diabetes mellitus in women: A linear dose-response meta-analysis of cohort studies. J. Diabetes Complications 31, 58–66 (2017).

Shi, M., Zhou, X., Zheng, C. & Pan, Y. The association between parity and metabolic syndrome and its components in normal-weight postmenopausal women in China. BMC Endocr. Disord 21, 8 (2021).

Cho, G. J. et al. The relationship between reproductive factors and metabolic syndrome in Korean postmenopausal women: Korea National Health and Nutrition Survey 2005. Menopause 16, 998–1003 (2009).

Nappi, R. E., Chedraui, P., Lambrinoudaki, I. & Simoncini, T. Menopause: a cardiometabolic transition. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 10, 442–456 (2022).

Pafili, K. et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease through the female lifespan: the role of sex hormones. J. Endocrinol. Invest 45, 1609–1623 (2022).

Lee C, Kim J, Jung Y. Potential Therapeutic Application of Estrogen in Gender Disparity of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease/Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Cells, 8 (2019).

Wang, X. et al. Hepatic estrogen receptor alpha improves hepatosteatosis through upregulation of small heterodimer partner. J. Hepatol. 63, 183–190 (2015).

Rui, W. et al. Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2-Related Factor 2 deficiency results in amplification of the liver fat-lowering effect of Estrogen. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 358, 14–21 (2016).

Hua, L. et al. Identification of hepatic fibroblast growth factor 21 as a mediator in 17beta-estradiol-induced white adipose tissue browning. FASEB J. 32, 5602–5611 (2018).

Gao, H. et al. Long-term administration of estradiol decreases expression of hepatic lipogenic genes and improves insulin sensitivity in ob/ob mice: a possible mechanism is through direct regulation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3. Mol. Endocrinol. 20, 1287–1299 (2006).

Li, L. et al. G protein-coupled estrogen receptor 1 ameliorates nonalcoholic steatohepatitis through targeting AMPK-dependent signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 300, 105661 (2024).

Itagaki, T. et al. Opposing effects of oestradiol and progesterone on intracellular pathways and activation processes in the oxidative stress induced activation of cultured rat hepatic stellate cells. Gut 54, 1782–1789 (2005).

Ladyman, S. R., Augustine, R. A. & Grattan, D. R. Hormone interactions regulating energy balance during pregnancy. J. Neuroendocrinol. 22, 805–817 (2010).

Walker, L. O. Managing excessive weight gain during pregnancy and the postpartum period. J. Obstet Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs 36, 490–500 (2007).

Meyer, D., Gjika, E., Raab, R., Michel, S. K. F. & Hauner, H. How does gestational weight gain influence short- and long-term postpartum weight retention? An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 25, e13679 (2024).

Al Mamun, A. et al. Association between gestational weight gain and postpartum diabetes: evidence from a community based large cohort study. PLoS ONE 8, e75679 (2013).

McClure, C. K., Catov, J. M., Ness, R. & Bodnar, L. M. Associations between gestational weight gain and BMI, abdominal adiposity, and traditional measures of cardiometabolic risk in mothers 8 y postpartum. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 98, 1218–1225 (2013).

Walter, J. R. et al. Associations of trimester-specific gestational weight gain with maternal adiposity and systolic blood pressure at 3 and 7 years postpartum. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 212(499), e491–e412 (2015).

Hill, B. et al. Is parity a risk factor for excessive weight gain during pregnancy and postpartum weight retention? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 18, 755–764 (2017).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (RS-2023–00220894). Additional support was provided by Korea University Guro Hospital (Z2300011) and a grant funded by Korea University (K2409361, K2428001, K2508621).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Concept and design: S.H.H., K.M.C. Statistical analysis: S.Y.H. Data interpretation: S.H.H., S.Y.H., K.M.C. Data collection and management: S.H.H., S.Y.H. Manuscript writing: S.H.H., K.M.C. Supervision and critical review: J.H.Y., N.H.K., H.J.Y., J.A.S., S.G.K., N.H.K., S.H.B.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hong, Sh., Hwang, S.Y., Yu, J.H. et al. The impact of parity on the risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease defined by hepatic steatosis index: A nationwide cohort study. Sci Rep 15, 26972 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11976-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11976-x