Abstract

Foam has been widely used for enhanced oil recovery (EOR) and CO2 sequestration due to its ability to improve sweep efficiency and control gas mobility. However, foam instability poses challenges for long-term applications. While nanoparticles have been explored as foam stabilizers, their high cost and limited availability hinder large-scale use. This study investigates red mud-derived nanoparticles (RMNPs), synthesized from industrial waste, as an affordable and sustainable alternative to traditional foam stabilizers. RMNPs were produced by ball milling at varying milling durations, achieving sizes below 200 nm. Characterization of the RMNPs was conducted using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX), zeta potential measurements, and particle size analysis. Foaming solutions were prepared with alpha-olefin sulfonate (AOS) anionic surfactant, with and without the RMNPs, in deionized water, seawater, and brines (NaCl and CaCl2), covering pH 3–11. Foam stability was evaluated via handshake tests and dynamic foam analyses using nitrogen and carbon dioxide gases. Results showed that incorporating RMNPs significantly enhanced foam stability, increasing foam half-life by up to 60% with nitrogen and 57% with CO2. Nanoparticles milled for 30 h yielded optimal performance, forming fine and uniform bubble structures. Zeta potential analysis confirmed strong hydrophilic properties of the RMNPs, promoting stability in aqueous solutions. pH sensitivity tests indicated optimal stability at pH 4–5, while highly acidic conditions (pH 3) negatively affected stability. This work highlights the potential of red mud-derived nanoparticles as a low-cost stabilizer for foam applications in EOR and CO2 sequestration, supporting further optimization under reservoir conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Injection of CO2 into underground geological formations has been proven effective technology, not only for enhanced oil recovery (EOR) applications, but also for permanent CO2 geo-sequestration. CO2-EOR has gained increasing attention due to the growing need to sequester large volumes of CO2 generated by anthropogenic activities, such as power generation1. The injected CO2 can be injected continuously or by alternation with water through the water-alternating-gas (WAG) injection mode2. However, the significant difference between the viscosity and density of the injected CO2 and reservoir fluids renders the process inefficient3. The low viscosity of CO2 (0.01–0.1 cP) compared with that of crude oil, whose viscosity is more than 10 cP in some reservoirs, results in viscous fingering, early CO2 breakthrough, and, ultimately, poor sweep efficiency4,5. Many approaches have been developed to mitigate the problem of viscous fingering, one of which involves using CO2 foams instead of continuously injecting CO26.

Foam is a two-phase fluid comprising a dispersion of a nonwetting gas in a continuous wetting liquid phase. The liquid phase is primarily a surfactant solution with a specific surfactant concentration, particularly above the critical micelle concentration (CMC)7,8. The gas bubbles in foams are separated from each other by a liquid film called foam lamellae, which forms the outer membrane of the gas bubbles9. The foam lamellas are stabilized by surfactants, which adsorb at the gas-water interface. The role of foam in the EOR process lies in two simultaneous factors: boosting the apparent viscosity of gas and reducing its relative permeability4,10. By trapping CO2 into bubbles, the foam increases flow resistance in porous media, inhibits gas channeling, and improves sweep efficiency and CO2 sequestration capacity11. However, the inherent thermodynamic instability of foam, caused by the deformable and fragile films of surfactant-stabilized bubbles, often leads to gas-liquid separation in porous media, thereby limiting its effectiveness12. Additionally, the adsorption of surfactants onto rock surfaces and their partitioning into crude oil further hinder the effective long-distance propagation of foam13. Foam destabilization occurs through three primary mechanisms: drainage, coarsening, and coalescence. Drainage refers to the gravity-driven removal of liquid from between bubbles, which promotes gas diffusion from smaller to larger bubbles (coarsening) and leads to the rupture of thin films separating adjacent bubbles (coalescence)14,15. Surface-active particles can simultaneously counteract all three destabilization mechanisms, enhancing foam stability16. Therefore, the use of amphiphilic materials such as polymers, surfactants, nanoparticles, or a combination of these can alleviate the instability of foam17,18.

The advancement in nanoscience over the past years has led to the introduction of nanoparticles (NPs) and nanomaterials (NMs) for foam stabilization, especially for applications in harsh underground conditions that compromise the stability of surfactants. Nanoparticles have been utilized to improve foam performance in the foam flooding process, with their foaming properties receiving considerable attention in recent years19,20,21. According to Chaudhry et al.22nanoparticles produced from clays, oxides, and organic and inorganic materials have demonstrated significant potential for stabilizing emulsion and foam by adsorbing at fluid-fluid interfaces, due to their high adsorption energy and thermo-chemical stability23,24. Nanoparticles with varying surface chemistries can serve as sole stabilizers for foams in bulk systems and porous media25,26. In addition to reducing the interfacial tension, the mixtures of surfactants and nanoparticles strongly adhere to the gas/water contact area, increasing the “structural disjoining pressure” and the interfacial area18,27. Moreover, the primary mechanism through which nanoparticles prevent foam coalescence, for example, is by limiting gas diffusion between bubbles, thereby enhancing the durability of each bubble28. More details based on foam stabilization with nanoparticles can be found elsewhere29. In this context, tremendous efforts have been devoted to developing various nanoparticles and nanomaterials to enhance foam stability. NPs can stabilize foam and withstand harsh reservoir conditions, resulting in lower mobility in porous media than CO2 alone. Among the nanoparticles that have been utilized for foam stabilization are silica oxide (SiO2), aluminum dioxide (Al2O3), Iron oxides (Fe2O3), zirconium oxide (ZrO2), titanium dioxide (TiO2), calcium carbonate (CaCO3)21,30,31,32.

Despite their effectiveness in improving foam stability, the commercial application of this technology requires cost-effective alternative nanoparticles that can be produced in the large quantities necessary for foam stabilization at the field scale33. Additionally, most commercially available nanoparticles exhibit either extreme hydrophobicity or hydrophilicity, rendering them non-surface active. In such instances, in-situ surface activation of nanoparticles presents a cost-effective alternative34. Researchers have explored the development of nanoparticles derived from readily available waste materials with no economic value to alleviate the cost and availability challenges associated with previously tested nanomaterials. This approach focuses on developing cost-effective nanomaterials and contributes to managing the waste materials, such as fly ash, red mud, and steel slag, that are produced in substantial quantities35,36,37. Most waste materials predominantly contain high proportions of key metals used as nanoparticles for foam stabilization, such as silica oxide, aluminum oxide, and iron oxide, making them excellent candidates for producing foam-stabilizing nanomaterials38,39,40. Therefore, utilizing these materials for the purpose of nanomaterial production would offer substantial economic and environmental benefits.

The development of nanoparticles from fly ash for foam stabilization has been proven effective by many researchers. The primary challenge in producing nanoparticles from fly ash lies in the technical complexities of the process41. Lee et al.33 explored the use of fly ash NPs for foam stabilization. Fly ash NPs were produced through two-stage grinding. It was observed that stable foam could not be attained when using a solution of 0.02 wt% Dodecyltrimethylammonium Bromide (DTAB) without the fly ash NPs. However, treating the fly ash nanoparticles with 0.02 wt% DTAB significantly increased the hydrophobicity of the NPs, resulting in better foamability and foam stability. Singh et al.13 utilized the ball milling process to produce nanoparticles from fly ash for CO2 foam stabilization and mobility control applications. At various concentrations, different surfactants, including anionic, cationic, and nonionic surfactants, were tested. Visualization of foam texture showed a fine texture using thermally treated fly ash (TTFA) nanoparticles combined with an anionic or nonionic surfactant at low concentrations. The flooding experiments demonstrated that the developed nanoparticles enhanced the anionic surfactant’s foam stability and resistance factor in the absence of oil. Adverse effects on foam stability were observed in the Berea rock sample when TTFA nanoparticles were added to the nonionic surfactant. Building upon the previous studies, Eftekhari et al.42 used high-frequency ultrasonic grinding to produce nanoparticles at a size of 100–200 nm from fly ash for foam stabilization. The foam’s foamability, strength, and stability generated by combining alpha olefin sulfonate (AOS) surfactant with the produced nanoparticles were investigated, both with and without oil. The results showed that the foam stability was improved when using a small concentration of the nanoparticles in the presence of oil. Additionally, the strength of the foam was better, as demonstrated by the core-flooding experiments through the Bentheimer core sample, which showed higher liquid recovery from the core. Using a two-stage grinding process, Guo et al.43 produced 40–80 nm fly ash nanoparticles to stabilize CO2 foam for EOR applications as part of carbon capture, utilization, and storage. Transmission electron microscopy and dynamic light scattering were used to characterize the uniformity and size of the dispersion of the NPs. Flow experiments were conducted using a microfluidic device based on a 2D representation of Berea sandstone rock. The produced NPs were combined with a mixture of the AOS and lauramidopropyl betaine (LAPB) surfactants, which showed significant foam stability with a half-life of up to 280 min. The displacement experiments using the NPs-assisted foam resulted in over 90% recovery of the additional oil after waterflooding through the microfluidic setup. Further research studies have also been published to investigate the use of fly ash as a source of nanomaterials for foam stabilization44,45,46,47. Further optimizing foam stabilization with fly ash nanoparticles remains necessary.

Another waste material is red mud, also known as bauxite residue, which is produced in large quantities as a byproduct of the Bayer process, a key process in the aluminum manufacturing industry48,49. On average, the production of one ton of alumina results in 1.0–1.5 tons of red mud, resulting in a global accumulation of over 66 million tons of red mud annually from aluminum manufacturing50,51. Extensive global research has also been conducted to develop cost-effective and sustainable methods for repurposing red mud waste. Researchers have explored various practical applications for red mud, including agriculture, construction, water management, pipeline coating, and waste gas treatment. Red mud has been utilized as an acidic soil amendment and in the production of bricks, ceramics, tiles, glazes, and polymer composite panels as a wood substitute52,53,54,55,56. Other applications include iron-rich cement, radiopaque materials, and CO2 sequestration using liquid carbon dioxide57,58,59. Red mud has also been utilized in the oil and gas upstream sector for oil well cement and drilling fluids applications60,61. However, these applications fall short of effectively utilizing the large quantities of red mud produced each year, most of which is discarded in ponds or landfills, leading to serious environmental and health concerns. Given the ever-increasing production of red mud, exploring alternative methods for its utilization is crucial.

Motivated by the successful use of fly ash waste material in producing nanomaterials for foam stabilization, red mud, with similar primary constituents such as silicon oxide, aluminum oxide, and iron oxide, could be a promising yet underexplored alternative. Several studies have reported the synthesis of nanomaterials from red mud for various applications. Most of these works focus on extracting metal oxides or applying red mud-derived nanoparticles in construction, water treatment, or catalyst production40,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69. Although Occhicone et al.66 recommended the use of the nano-magnetic material derived from red mud for application in the CO2 capture process, no real application was reported. Therefore, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, no published work has addressed the utilization of red mud-derived nanoparticles specifically for foam stabilization. Therefore, red mud was utilized in this work as a sustainable and cost-effective source for producing nanoparticles to stabilize foam.

This work involves synthesizing and characterizing red mud nanoparticles (RMNPs). Different characterization methods were employed to reveal the composition, size, morphology, and shape of the raw red mud and the produced RMNPs. Solutions prepared with AOS anionic surfactant were then blended with the produced RMNPs to prepare different foam solutions at various salinities, pH levels, and particle sizes. Zeta potential measurements and particle size analysis were also conducted to assess the stability of the solutions and the particle size of the RMNPs, respectively. Handshake tests were performed to provide preliminary insights about foam behavior with and without RMNPs. Finally, a dynamic foam analyzer was then used to evaluate the behavior and structure of foam generated with solutions blended with the RMNPs using either CO2 or N2. This study is the first to explore the use of red mud in producing nanoparticles specifically for foam stabilization. The findings highlight the potential of RMNPs as effective foam stabilizers, with promising results that warrant further research to optimize their performance under different conditions.

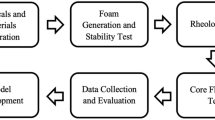

Methodology

The workflow involves the synthesis of the RMNPs from the as-received red mud using the ball-milling process. The produced RMNPs were characterized for their size, shape, composition, and morphology using different characterization techniques. The characteristics of foam generated with and without incorporating the RMNPs were evaluated using handshake tests and the ambient dynamic foam analyzer using different base solutions and different gases. The following subsections provide a detailed description of the experimental work conducted in this study. Figure 1 illustrates a summary of the workflow and key experimental steps undertaken. The photos of all the equipment and instruments used in this work are shown in Figure S1 in the supporting file.

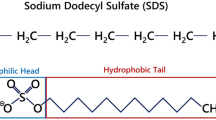

Materials

The red mud utilized in this study is a byproduct of the alumina production industry, sourced from a local alumina plant in Saudi Arabia. The anionic surfactant Alpha Olefin Sulphonate, provided by Sunita Hydrocolloids Inc., was used as the base for the foaming solutions. Salts of laboratory grade, purchased from different suppliers (e.g., Sigma Aldrich), were also used to prepare the various brines. Nitrogen and CO2 gases, supplied by a local gas company at high purity, were also used in this work in the foaming experiments using the dynamic foam analyzer.

Synthesis of red mud nanoparticles

The red mud raw powder was dried at 100 ℃ for 2 h to remove moisture before being ball-milled in a planetary ball mill (Micro Mill PULVERISETTE 7 premium line, FRITSCH-International). The dried red mud powder was placed in WC vials with WC balls of 5 mm diameter at a ball-to-powder ratio of 10:1. The milling process was conducted at 300 RPM under an argon atmosphere for 30 h, with samples collected at 6-h intervals for characterization.

Characterization of the red mud and produced RMNPs

The raw red mud sample was initially characterized using X-ray diffraction (XRD) with the EMPYREAN Diffractometer, Malvern PANalytical. The instrument operated over a 2θ range of 4°–70°, with an angular step size of 0.01°, indicating the incremental angle between successive measurements. Data acquisition was carried out at 45 kV and 40 mA. The resulting diffraction data were processed and quantified using the Rietveld refinement method implemented in HighScore Plus software. The system was equipped with a Pixcel1D detector, a reflection–transmission spinner sample stage, and a copper (Cu) X-ray source, generating Kα1 radiation at a wavelength of 1.54060 Å and Kα2 radiation at 1.54443 Å. These settings represent the default configuration commonly used in all XRD analyses70,71. X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis was also performed on the as-received red mud for elemental characterization. Particle size analysis was carried out using Anton Paar Litesizer 500 instrument. The produced nanoparticles were also characterized using energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) coupled with scanning electron microscopy (SEM). For this purpose, a Zeiss GeminiSEM 450 high-performance variable pressure Scanning Electron Microscope, equipped with a Schottky type field emission gun, was utilized, where 5 kV and 15 kV were applied to acquire the SEM and the EDX images, respectively. Further settings of the measurements are shown in the SEM and EDX images in the results section. The SEM provides visualization of the particles, showing their size, morphology, and shape after different grinding times. The EDX allows for the analysis of the chemical composition of the nanoparticles. Platinum was used as the coating material for the samples prepared for the SEM-EDX analysis.

Preparation of foaming solutions

Preparation of surfactant solutions

Different base fluids were used to prepare the surfactant solutions at AOS concentration of 0.5 wt%. The base fluids include deionized water (DIW), seawater brine (SWB), NaCl brine, and CaCl2. The prepared seawater was prepared by dissolving lab-grade salts in DIW at a concentration simulating the composition of Arabian Gulf water (see Table 1)72. NaCl brines were also prepared by dissolving NaCl in DIW at concentrations from 1 to 5 wt%. Similarly, CaCl2 solutions were prepared at concentrations of 0.1 and 0.15 wt%. The AOS was added to each fluid and left on a magnetic stirrer for sufficient time to ensure complete dissolution.

Preparation of solutions with RMNPs

The AOS solutions were then blended with the RMNPs at a concentration of 0.1 wt%, which is the most common concentration of NPs used for foam stabilization. The predetermined amounts of the RMNPs and the surfactant solution were mixed using magnetic stirrers and left overnight to ensure appropriate mixing. To ensure consistent experiments, the pH of the solutions was adjusted to the neutral range (~ 7) to eliminate the effect of pH on the tests where pH is not investigated. Therefore, for pH adjustment, a diluted hydrochloric acid (HCl) solution was gradually added to each solution while stirring.

To prevent the agglomeration of the RMNPs and, hence, reduce their size in the suspension, the solutions were put in an Ultrasonic Cleaner (Branson 8800 MH 20.8 L). The containers containing the foaming solutions with the RMNPs were properly sealed and immersed in the water path and left for sonication at predetermined times, where the sonication time was also examined. After sonication, the solutions were also allowed to settle down the suspensions of large particles, and the top part of the solutions was separated and used for the intended experiment.

Preliminary assessments

The stability and behavior of the prepared foaming solutions with and without the RMNPs were initially evaluated through zeta potential measurements and particle size analysis. Zeta potential (ζ) measurements were conducted to investigate the charge and hydrophobicity/hydrophilicity of the red mud nanoparticles. The measurements were performed using the Anton Paar Litesizer 500 instrument, which also allows measuring the particles’ size through dynamic light scattering, with a size range of approximately 3.8 nm to 100 μm. This method was, therefore, utilized to characterize the size of the produced nanoparticles. The prepared solutions containing the RMNPs were left to allow the large particles to settle, and the measurements were performed on the upper part of the solutions.

Handshake tests were also conducted to assess the role of RMNPs in foam stabilization. Different sets of solutions were tested to investigate different parameters, including the grinding time of the RMNPs (i.e., size and shape), salinity, and pH. The tests were conducted by adding 5 mL of each foaming solution to long (15 cm) capped test tubes (Fisherbrand®) with a capacity of around 30 mL. Each tube was hand-shaken for around 10–15 s. The tubes were then left on the bench, and the foam behavior was continuously monitored; images of the foam were also taken. The following subsections provide details of the tested set of solutions. To ensure rigorous evaluation, all experimental conditions were replicated with and without the inclusion of RMNPs, enabling a clear assessment of their specific impact on foam behavior.

Role of ball milling and sonication times

As mentioned previously, the ball milling time continued for 30 h, and the samples were collected at 6-h intervals for characterization. This resulted in five samples of the milled RMNPs and the raw red mud (i.e., the result is a total of 6 samples). Therefore, each sample was used to prepare a foaming solution in DIW or SWB, where the zeta potential and particle size were analyzed. The effect of sonication time was also investigated (i.e., 4, 6, and 8 h for DIW and 2, 4, and 6 h for SWB), and the measurements were performed after each sonication stage.

Effect of pH

pH is an important parameter that affects the performance of nanoparticles in foam stabilization. Therefore, different acidity and alkalinity cases were studied. The tests were performed at different pHs ranging from 3 to 11. For acidic solutions, the pH was adjusted by gradually adding diluted HCl to each solution while stirring until the desired pH was reached. For basic solutions, a diluted solution of KOH was used to increase the pH by gradual addition to the foaming solution while stirring.

Effect of salinity

The varying composition of electrolytes in formation water, along with high salinity, makes salinity a critical factor influencing foam generation and stability. It affects not only surfactant adsorption at the interface but also the stability of nanoparticles within the system73. Therefore, the effects of salinity and different salts on the performance of foams with and without RMNPs were investigated using five solutions of NaCl (1–5 wt%), two solutions of CaCl2, a solution of seawater, and a solution of double-concentrated seawater.

Foam structure analysis

Figure 2 shows a schematic diagram of the dynamic foam analyzer (DFA) manufactured by KRÜSS Scientific, Germany. The setup consists mainly of a glass column, height sensors, a gas source, a camera, and a data acquisition system. The 2D foam structure is visualized by a prism that is attached to the glass column, while the bubble size is measured through a calibration grid. The height and volume of the foam are detected and measured using a line sensor with the aid of a linear light-emitting diode (LED) panel. The measurements begin by gently adding 50 mL of the foaming solution into the bottom of the glass column using a syringe. The foam was generated by injecting gas (either CO2 or nitrogen) from the bottom of the column at an injection rate of 0.7 L/min. Filter paper with a size ranging from 16 to 50 μm is used at the bottom of the column to help uniformly generate the foam74. The results are analyzed using the DFA software, which provides bubble size, bubble count, foam height, foam volume, and their decay with time. The tests performed using the foam analyzer include three sets of experiments as summarized in Table 2.

Results and discussion

The following subsections present and discuss the results of the complete analysis and experimental work conducted to evaluate the role of the red mud-derived nanoparticles in foam stabilization. These include the results of characterization of the Raw RM and RMNPs, the results from preliminary assessments, and the results from the dynamic foam analyzer.

Characterization of the raw RM and synthesized RMNPs

The red mud’s chemical composition, structure, morphology, and particle size were analyzed using different analytical tools such as XRD, XRF, SEM-EDX, and a particle size analyzer.

The XRF analysis was used to reveal the oxide composition of the red mud sample used to produce RMNPs. The oxide composition of the Raw RM sample using XRF is depicted in Fig. 3. The error bars correspond to the standard deviation of the measurements. The concentrations are as follows: Fe2O3 (42.97 ± 3.82%), Al2O3 (32.91 ± 1.79%), SiO2 (17.61 ± 1.32%), CaO (4.81 ± 1.1%), and minor of other elements. The XRD analysis of the received red mud, illustrated in Fig. 4, confirms the existence of various crystalline phases, predominantly Fe2O3 (hematite), Al2O3 (alumina), CaCO3 (calcium carbonate), SiO2 (silica), TiO2 (titanium dioxide), and Na₈Al₆Si₆O2₄Cl2 (sodalite). Hematite is the predominant phase, as evidenced by its pronounced diffraction peaks, confirming the higher iron content of red mud, a defining characteristic of bauxite residue. The presence of alumina indicates residual aluminum from the Bayer process, whereas the sodium aluminosilicate phase (sodalite/cancrinite) results from the reaction of silica and alumina with sodium hydroxide under higher temperatures. The presence of calcium carbonate is due to the addition of lime during processing. The crystalline structure of these phases indicates considerable stability.

SEM imaging was performed to characterize the particle size distribution and morphology of the red mud at various milling times. Figure 5 presents the SEM images of the as-received red mud (Fig. 5a) and ball-milled RMNPs at different milling times, including 6 h (Fig. 5b), 12 h (Fig. 5c), 18 h (Fig. 5d), 24 h (Fig. 5e), and 30 h (Fig. 5f) with a scale of 400 nanometers. The images show that the as-received red mud consists of equiaxed particles with nearly spherical shapes. Figure 5b and c reveal the presence of some agglomerations at the early stage of milling due to particle refinement and competing mechanisms of particle welding and fracture. In addition, nanoparticles were combined into agglomerates, which were held together by weaker forces such as electrostatics, van der Waals, and capillary effects. With extended milling time, the particle assize refined and decreased up to 30 milling hours, contributing to increasing surface area (Fig. 5f).

Overall, the SEM images showed that the nanoparticles derived from the red mud utilized in this study appear in needle- or fibril-shaped particles along with equiaxed particles. However, prior studies using red mud indicate that the shape of the red mud particles may vary depending on the source of the red mud and the treatment type. Therefore, some studies showed that red mud particles can be spherical-shaped69,75,76needle- or fibril-shaped40,77sheet-like78or crystalline-like68,79 particles. The needle- or fibril-shaped particles offer a higher specific surface area than spherical particles, due to their high aspect ratio and numerous contact points. As a result, they can form highly entangled networks even at low concentrations, enhancing the strength and elasticity of the interfacial film on the surface of foam80. Additionally, the unique shape of elongated particles allows them to create osmotic networks more efficiently than spherical particles, which typically interact at a single point. The aggregation of fibrous particles can significantly enhance the viscosity of the suspension, contributing to the formation of a more stable foam81. This network formation also increases the solution’s viscosity by trapping liquid within its structure, thereby altering the system’s rheological behavior32.

Energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) analyzed the elemental composition of RMNPs, shown in Fig. S2 of the supplementary file. The EDX was conducted on various spectra from RMNPs to examine differently shaped particles. The table below the image highlights key elements: Fe, Al, Si, Ca, and Na. EDX results confirm that primary elements from the original red mud are retained, supporting the structural integrity of milled particles.

A particle size analyzer was used to determine the precise particle size distribution of the red mud milled for 30 h. The distribution (D) is represented by three different values: D10 indicates 10% of particles smaller than the captured data. D50 represents the median particle size distribution, while D90 indicates that 90% of all particles are smaller than the captured data size. The analysis revealed a D10 of 131 nm, D50 of 203 nm, and D90 of 321 nm.

Results of the preliminary assessments

Effect of milling and sonication times

Preliminary assessments were conducted at different stages of testing the RMNPs derived at different milling times. Figure 6 shows the nanoparticles’ hydrodynamic diameter, representing the average size of particles in the suspension. The 0 h in the milling time represents the raw red mud (RawRM), which was used as received. Without sonication, all the nanoparticles showed an average particle size greater than 300 nanometers, even after milling for 4 h. However, the sonication of the samples at different times showed that smaller nanoparticles could be produced from the red mud agglomerated together due to electrostatic attractions. Different derived RMNPs from varying milling durations also exhibited distinct average particle sizes after sonication. While some derived RMNPs achieved the smallest average particle size of around 200 nm after 4 h (e.g., 0 h-RM, 6 h-RMNPs, and 24 h-RMNPs), others required 8 h of sonication time to reach this low average particle size (i.e., 12 h-RMNPs). However, 6 h of sonication time resulted in larger particles and re-agglomeration of particles, which was observed in most of the produced RMNPs, except for the 12-h-RMNPs.

It can be posited that sonication alone might be sufficient to generate nanoparticles from unprocessed red mud, thereby rendering milling an unnecessary step. Nevertheless, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images indicate that nanoparticles synthesized from raw red mud predominantly display a needle-like morphology. These needle-shaped particles may induce a phenomenon known as the “needling effect,” which can negatively impact the stability of the foam. This effect transpires when sharp particles penetrate the foam-water interface, leading to a rapid collapse of the foam and expediting its deterioration82. Consequently, milling is imperative, not only for reducing particle size but also for altering their shape and morphology, which will significantly affect foam stability, as substantiated by the SEM images.

Figure 6 also displays the corresponding zeta potential for the solution prepared using RMNPs at different milling and sonication times in DIW. Zeta potential is considered an effective measure of particle charge, as directly measuring the surface charge of particles is not feasible83. Therefore, the measurements indicate that the red mud particles are hydrophilic due to the negative values of the zeta potential. The measured zeta potential of the red mud in DIW water without the AOS is -21.6 ± 0.47 mV. The magnitude of the zeta potential increased to 50 mV when used with the AOS. The increase in the magnitude with the AOS reflects the increased hydrophilicity and, hence, more stability in suspension. In addition, the figure shows large magnitudes of zeta potential even at high average particle sizes, which also shows increasing the magnitude of zeta potential with the decrease in the hydrodynamic diameter for each set. This relation is important, as the zeta potential can provide an indication of the average particle size, suggesting that large particles should be avoided to prevent blockage in the porous media. This agrees with the suggestion of Eftekhari et al.42 who stated that the particles may agglomerate and form large particles that result in blockage in the porous media, as in the case of fly ash nanoparticles, as inferred from the zeta potential measurements.

Images of the generated foam through handshaking using RMNPs that were produced at different milling times are shown in Fig. 7. The shaking was performed after the last sonication time of 8 h for the DIW-based solutions. In each image, the vial at the most left contains the solution without the RMNPs while the remaining are those that are blended with RMNPs. The solutions prepared in DIW only showed slight variations in the behavior of the foam generated by handshaking with and without the RMNPs. However, including the 18 h-RMNPs produced weak foam with a small volume compared to the other RMNPs. This could be attributed to the disappearance of the needle-shaped particles as demonstrated by the SEM images. The reddish color in the liquid phase shown by the vials containing the RMNPs reflects the stability of the RMNPs in the suspension, where the RMNPs remained in suspension for a long time.

Figure 8 shows the hydrodynamic diameter and zeta potential of the solution prepared in SWB with RMNPs at different milling and sonication times. Without sonication, all the nanoparticles showed an average particle size greater than 1,000 nanometers (1 μm), even after milling for a long time. The results also show that the sonication of the samples could not deagglomerate the particles and still showed hydrodynamic diameters closer to 1 μm, except for samples milled for 12 h, 24 h, and 30 h. These samples exhibited a hydrodynamic diameter of approximately 100 nm after only 2 h of sonication. Other samples required sonication for almost 6 h to achieve hydrodynamic diameters close to 100 nm. From this, we conclude that, for preparing solutions in SWB, milling times of 12 h, 24, or 30 h should be selected for synthesizing the RMNPs. The selection of the best choice will be based on the performance of the foam, which is discussed later. The magnitudes of the zeta potential for all samples are close to 20 mV, reflecting the influence of salinity on the stability of the suspensions. In saline solutions, the anionic AOS surfactant forms negatively charged micelles due to the presence of electrolytes. These micelles create an electric double layer, influencing their interaction with RMNPs. Given the negative charge of RMNPs, the surfactant micelles likely generate a negative background potential, causing electrostatic repulsion between the surfactant and RMNPs. This repulsion pushes the particles closer together, promoting their agglomeration84. This behavior was reflected in the zeta potential, which showed a decreased magnitude, and in the particle size analysis, which indicated larger average particle sizes.

Unlike the solutions prepared in DIW, the figure shows no direct relationship between the average particle size (hydrodynamic diameter) and zeta potential, where increasing the particle size does not correspond to a decrease in the magnitude of zeta potential. This can be related to the discussion of Liu et al.84 who stated that the decrease in zeta potential does not necessarily correlate with the increase in the average particle size of silica nanoparticle suspensions in saline solutions. As a result, the agglomeration of nanoparticles should not be expected even at low magnitudes of zeta potential because the decrease in the repulsive interaction can be larger than the attractive interactions.

Images of the generated foam by hand-shaking for solutions prepared in SWB with and without the RMNPs, which were produced at different milling times, are shown in Fig. 9. The shaking was performed after the last sonication time of 6 h. Initially, the solutions prepared in SWB only showed slight variations in the behavior of the foam generated by handshaking with and without the RMNPs (0 min). As time progressed, the foam generated with solutions containing the RMNPs showed better foam texture than those without the RMNPs (5 min). After 15 min, the foam, including the 30 h-RMNPs, showed the finest structure among the other used RMNPs. This implies that the 30 h-RMNPs are the best choice for preparing foaming solutions in SWB. A light reddish color is observed in the liquid phase of the vials containing the RMNPs, attributed to the influence of salinity on the stability of the RMNPs, resulting in fewer particles remaining in suspension.

pH effect

Figure 10 shows the effect of the pH on the zeta potential of the foaming solutions containing RMNPs with DIW as the base fluid for all solutions. The results show that the zeta potential was minimum (-43 mV) at a low pH of 3. This is because a large amount of diluted HCl had to be added to the solution to reach this pH value, although the AOS solution in DIW was stable at this pH. The leaching of the RM was caused by the addition of HCl, resulting in an initial increase in pH as HCl was added to the solution. The solutions exhibited good stability near neutral pH, with the pH values decreasing and then increasing. Even without adjusting the pH of the solution to neutral, the solutions are still in the stabilized region (i.e., pH = 9, ζ > 50 mV).

Images of the generated foam through handshaking using RMNPs at different pH are shown in Fig. 11. In each image and for each pH, the vial to the left of each pH set is for the solution without the RMNPs, while that to the right is for the solution with the RMNPs. The images show that the pH of the foam generated by the handshaking did not significantly influence it. However, the images indicate that the foam generated with RMNP-containing solutions at a pH of 3 was unstable, with a significantly lower foam volume than other solutions, including the AOS solution without RMNPs. The pH tests indicated that optimal foamability occurs at a pH of 4–5, corresponding to the highest zeta potential, as indicated by the handshake test. It is also clear from the color of the liquid in each vial, where those with a clear reddish color correspond to pH levels of 4, 5, or 9.

Salinity effect

Figure 12 shows the zeta potential of the foaming solution prepared in different base fluids with varying salinities. For the DIW-based solutions, the magnitude of ζ was around 50 mV. The use of NaCl reduced the magnitude of zeta potential, which decreased from around 39 mV at 1% NaCl to 25 mV at 5% NaCl. Images of the generated foam through handshaking using RMNPs at different salinities and NaCl at different concentrations are shown in Fig. 13. Similarly, in each image and for each brine set, the vial to the left of the brine set is for the solution without the RMNPs, while that to the right is for the solution with the RMNPs. Better foam is obtained when using RMNPs. The improvement in the performance is more pronounced at higher concentrations of NaCl, demonstrating the effectiveness of the RMNPs in enhancing foam properties at extreme salinity conditions.

For solutions prepared in CaCl2 brines, the magnitude of zeta potential was around 22 mV at 0.10% CaCl2 and around 18 at 0.15% CaCl2. The foam generated using CaCl2 solutions is shown in the four vials to the left of each image in Fig. 14. The images show that using RMNPs resulted in better foam performance generated by handshaking. The other four vials to the right of each image in Fig. 14 also show the foam generated from solutions prepared in SWB and double-concentration SWB. The images also show improved foam performance when the RMNPs are incorporated compared to those without the RMNPs.

Foam structure analysis results

This section presents the results of foam analysis conducted using the ambient dynamic foam analyzer. It is divided into two subsections: one covering the results of foam generated with nitrogen and the other focusing on foam generated with CO2. The experimental design incorporated appropriate control samples by systematically comparing each foaming solution with and without RMNPs under identical testing conditions, ensuring data reproducibility and clarity in interpreting the nanoparticle effect.

Foam generated with N2

Figure 15 summarizes the results from the height analysis of foam generated by nitrogen injection through various foaming solutions. The figure displays the foam half-life (tH50%), initial foam volume, and the liquid drainage half-life time (tFLS50%). Foams’ half-life is an important parameter that reflects the stability of foam. It represents the time at which foam loses 50% of its height or volume85. The liquid drainage half-life (tFLS50%) corresponds to the time required for the foam to drain 50% of the liquid content. Foam liquid stability (FLS) indicates the foam’s ability to retain liquid, which directly influences its dryness level86. For the interpretation of tH50% and tFLS50%, the higher these values are, the better the stability of foam is87. The initial foam volume represents the volume of foam generated once the gas injection through the porous filter paper ceases. It indicates the foamability of foaming solutions, representing their ability to generate foam irrespective of their specific properties.

For solutions prepared in DIW, foam half-life time was approximately 756 s for solutions prepared with AOS only. The addition of 6 h-RMNPs increased the foam half-life to around 1,211 s, enhancing foam stability by approximately 60%. Incorporating 30 h-RMNPs resulted in a slight 5% increase in foam’s half-life, with a corresponding foam half-life of 794 s. For SWB-based solutions, the foam half-life was approximately 1,285 s for the solution without the RMNPs. Incorporating 30 h-RMNPs significantly improved foam stability by approximately 36%, increasing the foam half-life to 1,743 s. However, adding 6 h-RMNPs had an adverse effect, reducing the foam’s half-life to 950 s, necessitating further investigations and demonstrating that the 30 h-RMNPs are the optimal option for foam stabilization. The foam half-life time of the 3%-NaCl-based solutions was approximately 461 s without RMNPs. Adding 30 h-RMNPs significantly enhanced foam stability by more than 57%, increasing the foam half-life time to 727 s.

For the initial foam volume, no significant difference was observed among the foam volumes in all the base fluid groups; solutions prepared in DIW resulted in a similar foam volume, ranging from 203 to 260 mL. Solutions prepared in SWB had initial foam volume ranging from 209 to 253 mL, while those prepared in 3% NaCl had foam volume of around 200 mL. The slight variation in the foamability of all foaming solutions should not be considered significant, especially given the possibility of experimental errors. Therefore, it can be concluded that salinity and the presence or absence of RMNPs have no notable effect on foamability. Furthermore, it is important to emphasize that foamability does not necessarily correlate with foam stability. A similar observation is noticed with the liquid drainage half-life time, where all DIW-based solutions resulted in foams with the same tFLS50% of around 112 s. Foams generated with SWB- or 3%-NaCl-based solutions showed no significant variations in the tFLS50%, with an average value of around 80 s.

Figure 16 presents the initial mean-bubble area (MBA, µm2) of foams generated with the different foaming solutions using N2. It provides insight into the initial texture of the generated foam and its coarseness, where a large MBA corresponds to a coarse foam. For foams generated with DIW-based solutions, there is no specific trend for the initial mean bubble area. However, the least MBA corresponds to the solution that incorporated the 6 h-RMNPs (11,000 µm2), reflecting the effectiveness of the 6 h-RMNPs in improving the structure of the foam generated by these solutions. For foams generated with SWB-based solutions, the initial mean bubble area for the foam without the RMNPs was the highest, indicating a foam with coarse bubbles. However, incorporating the RMNPs resulted in finer bubbles due to the decreased initial mean bubble area, with the least initial mean bubble area corresponding to the solution that incorporated the 30 h-RMNPs (19,000 μm²). Finally, for foams generated with 3%-NaCl-based solutions, there was a slight increase in the mean bubble area when incorporating the RMNPs.

Figure 17 summarizes the initial bubble count per unit area (mm−2) and initial bubble radius (µm) of foam generated by nitrogen injection through the different foaming solutions. For foams generated with solutions prepared in DIW, the highest initial bubble count corresponds to the solutions with 6 h-RMNPs, with an initial bubble count of around 90 mm−2. There are no significant variations in the initial average bubble radius for the foam generated with all solutions prepared in DIW. However, the better foam corresponds to foam where 6 h-RMNPs are incorporated, due to the smallest initial average bubble radius of 55 μm. For foams generated with solutions prepared in SWB, the bubble count increased from approximately 39 mm−2 for the foam without RMNPs to 56 mm−2 and 53 mm−2 for foams with 6-h-RMNPs and 30-h-RMNPs, respectively. The average bubble radius was around 79 μm for foam without the RMNPs. Blending the solution with the RMNPs resulted in a smaller initial average bubble radius of less than 75 μm for both 6-hr-RMNPs and 30-hr-RMNPs, indicating a finer foam and, hence, a better foam structure when including the RMNPs. For the 3%-NaCl-based solutions, however, there was no improvement in the foam structure with the RMNPs, as indicated by the initial bubble count and the initial average bubble radii.

Figure 18 shows the bubble count behavior for solutions prepared in DIW (left) and SWB (right) over time. The curves indicate that the bubble number for cases without RMNPs declines faster than for those with RMNPs. To illustrate, the left figure shows that the bubble count for the foam generated with the plain AOS solution in DIW declined sharply for around 12 min, after which the decline became gentle. For the cases where the RMNPs are included, the decline was sharp for only around 8.5 min after which the bubble count decline became slow. Overall, as time progresses, the bubble counts for foams generated with solutions containing RMNPs are higher than those without the RMNPs, with the 30 h-RMNPs exhibiting the highest bubble count. To illustrate, a larger bubble count per unit area indicates the persistence of bubbles with small sizes and, hence, finer bubbles over time. The dominance of finer bubbles also corresponds to higher foam density and better foam rheology88. For foam generated with solutions prepared in SWB, the decrease in the bubble count for the solution without RMNPs and with the 30 h-RMNPs was almost the same. However, the highest number of bubbles with time corresponds to 30 h-RMNPs, reflecting better foam structure with RMNPs.

Figure 19 illustrates the mean bubble area alongside the average bubble radius for solutions prepared in DIW. The curves representing the mean bubble area with time exhibit a two-stage pattern. In the initial phase, the mean bubble area experiences a rapid increase, followed by a gradual increase in a subsequent stage. Both stages demonstrate an almost linear relationship with time. These observations suggest that the foam initially coarsens at a rapid rate, which subsequently slows over time. The results indicate a considerable increase in the mean bubble area within the first 10 min, followed by a slight increase in the mean bubble area thereafter. To evaluate the inclusion of the RMNPs, it is evident that lower mean bubble areas correspond to foams generated with solutions containing RMNPs. Given that the mean bubble area indicates the coarsening rate of the bubbles over time, this suggests that the inclusion of RMNPs effectively reduced the coarsening rate of the foam. The average bubble radii also consistently increased throughout the experiment, as illustrated in the accompanying figure to the right.

The results of the mean bubble area and average bubble radius of foams generated with solutions prepared in SWB are illustrated in Fig. 20. The figure on the left indicates that the mean bubble area sharply increased over time, stabilizing after approximately 13 min. Notably, the foam containing the 6 h-RMNPs demonstrated the highest mean bubble area and largest average bubble radius, whereas the formulation prepared with the 30-h-RMNPs displayed the lowest mean bubble area alongside the largest average bubble radius. The 30-h-RMNPs represent the optimal choice for foam stabilization in SWB-based solutions. The average bubble radii over time, depicted to the right of the figure, further illustrate similar sharp increases in the average bubble radii as time progresses. The results of the structural analysis of the foam generated with the 3%-NaCl-based solutions with N2 are provided in the supplementary file (Figs. S3 and S4).

Figures 19 and 20 also show that the overall structure of foams generated with solutions prepared in the SWB is relatively better than that of foams generated with DIW-based solutions. According to Tang et al.29unlike surfactants, previous observations on nanoparticle-enhanced foams showed that increasing salinity does not adversely affect the stability of nanoparticle-reinforced foams but instead increases foam stability until reaching a critical salt concentration89,90,91,92. To illustrate, in nanoparticle-stabilized foams, the presence of electrolytes leads to the compression of the diffuse electric double layer (EDL) surrounding the particle surfaces, which in turn reduces the electrostatic repulsion. An appropriate concentration of salt ions promotes particle adsorption at the gas-liquid interface, boosting the energy barrier between bubbles, preventing coalescence, and enhancing foam stability. Additionally, higher salinity promotes the aggregation of nanoparticles, leading to the formation of weak particle gels with limited yield stress, which serves as a crucial mechanism for improving foam stability93,94. These observations explain the relatively better performance of foams generated with solutions prepared in SWB.

A visualization of the bubble structure behavior of the foam is shown in Table 3 for solutions prepared in DIW using N2 injection. The images clearly show poor performance with the foam generated where the RMNPs are not utilized. This is due to the non-uniform distribution of bubble sizes and the rapid appearance of large bubbles. However, adding either the 6 h-RMNPs or the 30 h-RMNPs resulted in a better foam structure, demonstrated by the larger number of small bubbles and the slowness in their coarsening for more than 20 min. The small bubbles persisted longer than the foam without the RMNPs in these cases. For solutions prepared in SWB, the images presented in Table 4 show a poor performance with the foam generated in the absence of the RMNPs. This is related to the nonuniform distribution of the bubble sizes and the fast appearance of the large bubbles after 10 min. However, the addition of the 30 h-RMNPs resulted in a better foam structure as indicated by the larger number of small bubbles, which also persisted for more than 20 min. The enhanced foam structure can be attributed to the role of RMNPs in slowing lamella thinning, which prevents bubble coalescence by reducing gas diffusion and limiting liquid drainage28,95. Since the liquid drainage was almost the same for the cases with and without the RMNPs as seen in the previous discussions, it can be concluded that incorporating the RMNPs could reduce gas diffusion between bubbles. Finally, for foams generated with solutions prepared in 3% NaCl, Table 5 shows images with finer bubbles generated when incorporating the 30 h-RMNPs for 15 min with uniform distributions of sizes. This structure continued for more than 15 min. However, the absence of the RMNPs caused a fast coarsening of the foam starting after 10 min, after which the large bubbles started to appear, and the bubble size distribution became nonuniform.

Foam generated with CO2

Figure 21 summarizes the results of the height analysis of foam generated by CO2 injection through different foaming solutions. The figure displays the foam half-life, initial foam volume, and liquid drainage half-life (tFLS50%). For foams generated with solutions prepared in DIW, the foam half-life time was approximately 251 s for the plain AOS solution without the RMNPs. Blending the solutions with the 6 h-RMNPs increased the foam half-life to about 285 s, representing a 14% improvement in foam stability. The addition of 30 h-RMNPs also resulted in a slight increase of 10%, with a corresponding foam half-life of 275 s. For SWB-based solutions, the foam half-life was approximately 683 s without RMNPs. Including the 30 h-RMNPs, which had no significant impact on foam stability, yielding a half-life of 653 s. Similar to the N2 case, adding 6 h-RMNPs adversely affected foam stability, reducing the half-life to 338 s. The half-life of foam generated with the 3%-NaCl-based solutions was approximately 280 s without RMNPs. Adding 30 h-RMNPs significantly improved foam stability by more than 57%, increasing the foam half-life time to 442 s. For foam volume, no significant difference was observed in the foam volume in all the base fluid groups; that is, foam generated with solutions prepared in DIW resulted in a similar foam volume of around 200 mL, foam generated with solutions prepared in SWB had initial foam volume ranging from 200 to 250 mL, while foam generated with solutions prepared in 3% NaCl had initial foam volume ranging from 230 to 300 mL. A similar conclusion is therefore drawn regarding the foamability of the foaming solutions with the CO2 as in the case of N2. However, the foam volume generated by CO2 is less than that generated by N2 at the same gas injection rate (0.7 L/h). This is because the density of CO2 (1.97 kg/m3) is higher than that of N2 (1.25 kg/m3), and foaming requires exceeding the minimum superficial velocity, which depends on the gas type. To illustrate, higher gas density necessitates increasing the injection velocity and rate to achieve the same foam volume obtained by a lighter gas. Hence, a denser gas demands a higher velocity to initiate foam generation96. For the liquid drainage half-life time, the DIW-based solution showed the same tFLS50% of around 90 s while the SWB- and 3%-NaCl-based solutions showed tFLS50% of around 85 s.

Figure 22 presents the initial mean-bubble area (µm2) of foams generated with the different tested solutions using CO2. For foams generated with DIW-based solutions, similar to the N2 case, there is no clear trend for the initial mean bubble area. However, the least mean bubble area corresponds to the solution that incorporated the RMNPs with foam, including the 30 h-RMNPs, which resulted in the least initial mean bubble area. For foams generated with SWB-based solutions, the initial mean bubble area for the foam without the RMNPs was the highest. However, incorporating the 6 h-RMNPs resulted in the least initial mean bubble area. For foams generated with 3%-NaCl-based solutions, there are no changes in the initial mean bubble area with and without incorporating the RMNPs.

Figure 23 provides a summary of the structure analysis of the foam generated by CO2 injection through the different foaming solutions. For foams generated with solutions prepared in DIW, the highest initial bubble count corresponds to the solutions with 30 h-RMNPs, with a total bubble count of around 72 mm− 2. There are no significant variations in the initial average bubble radius for the foam generated with all solutions prepared in DIW. The largest initial average bubble radius was approximately 70 μm, corresponding to the foam with the 6-hr-RMNPs. However, incorporating the 30 h-RMNPs resulted in a foam with an initial average bubble radius of 65 μm, which is almost identical to that without the RMNPs.

For solutions prepared in SWB, the foam generated where RMNPs are not included has an initial bubble count of around 43 mm− 2 and the adjacent initial average bubble radius was the highest with a value greater than 80 μm. Incorporating the 6 h-RMNPs or the 30 h-RMNPs resulted in foam with initial bubble counts of 58 mm− 2 or 51 mm− 2, respectively. The corresponding initial average bubble radii for incorporating either the 6 h-RMNPs or the 30 h-RMNPs are 70 μm and 75 μm, respectively. Interpreting these results in isolation may be misleading since they indicate that incorporating the 6 h-RMNPs results in better foam structure due to the larger initial bubble count and the least initial average bubble radius. However, the foam half-life time with the 6 h-RMNPs was lower than the plain AOS surfactant, and the foam decayed rapidly. Therefore, compiling all results from foam stability and foam structure analysis is essential to gain deeper insights and a more comprehensive assessment of the foam properties and behavior. For the foam generated with the 3%-NaCl-based solutions, there is no noticeable change in the formability where the initial bubble counts and the initial average bubble size were 48 mm− 2 and 78 μm, respectively, for foams with and without the RMNPs.

The behavior of foam bubble count with time is shown in Fig. 24 for foams generated with solutions prepared in DIW and SWB. It can be seen from the figure that the bubble count for the case where RMNPs are not present is reducing at a rate sharper than the cases where RMNPs are incorporated. To illustrate, Fig. 24-left shows a significant drop in the bubble count within 200 s for the case without the RMNPs. Using either the 6 h-RMNPs or 30 h-RMNPS resulted in a slow decline in the bubble for more than 200 s, after which the bubble count stabilized. Moreover, the bubble count in cases where RMNPs are present is higher than in cases where no RMNPs were used. For foams generated with SWB-based solutions, Fig. 24-right shows a sharp decline of the bubble count and the complete disappearance of the bubble count in less than 500 s when the 6 h-RMNPs were used. The use of the 30 h-RMNP resulted in a trend similar to that of the plain AOS solution, with a slightly higher bubble count. The bubble count declined sharply in the first 500 s and then decreased slowly. Overall, incorporating the RMNPs resulted in a better bubble count with time and, hence, a better foam structure, as a higher bubble number corresponds to higher foam density and better foam rheology.

For solutions prepared in DIW, the mean bubble area of the foam generated with the plain AOS solution increased sharply for the first 200 s and reached a maximum value after around 270 s (Fig. 25-left). The MBA then decreased due to the disappearance of the bubbles. Using either the 6 h-RMNPs or the 30 h-RMNPs resulted in a gradual increase in the MBA until after 250 s, after which the MBA stabilized. Similar trends were observed in the average bubble radii, which increased sharply for the foam without the RMNPs. The increase was steady for solutions incorporating either the 6 h-RMNPs or the 30 h-RMNPs. Overall, the incorporation of the RMNPs resulted in a lower MBA, indicating that the use of the RMNPs reduced the coarsening rate of CO2 foam.

For foam generated with the solutions prepared in SWB, the results of the mean bubble area and average bubble radius are shown in Fig. 26. The figure to the left shows that the mean bubble area sharply increased with time, with the sharpest increase corresponding to the foam with the 6 h-RMNPs. The MBA sharply increased in less than 400 s, after which it started to level off, and the foam ultimately disappeared. For the foam without the RMNPs and the 30-h-RMNPs, the MBA increased sharply in the first 500 s, followed by a gradual increase in the MBA. Overall, using the 30 h-RMNPs resulted in foam exhibiting the least MBA with time compared to that without the RMNPs. The figure to the right shows the average bubble radius, which shows a continuous increase for the foams with and without the RMNPs. The foam generated with a solution containing the 6 h-RMNPs showed the largest average bubble radius, while that containing the 30 h-RMNPs showed the least average bubble radius. These observations indicate that the 30 h-RMNPs is the best choice for CO2 foam stabilization in SWB-based solutions. The results of the structural analysis of the foam generated with the 3%-NaCl-based solutions with CO2 are also provided in the supplementary file (Figs. 5S and 6S).

A visualization of the bubble structure behavior of the foam is presented in Table 6 for solutions prepared in deionized water (DIW) using CO2 injection. The images clearly show a poor performance with the foam generated when the RMNPs are not utilized, where the foam starts to coarsen after 3 min, resulting in fewer bubble counts. However, adding either the 6 h-RMNPs or the 30 h-RMNPs resulted in a better foam structure for more than 10 min. This is indicated by the larger number of bubbles and the slowness in their coarsening. Despite the coarsening of the bubbles in the case of the RMNPs, the bubble size distributions remain uniform throughout the experiment.

For solutions prepared in SWB, the images presented in Table 7 show the structure of the foam generated by CO2 injection. The images also show a poor performance with the foam generated in the absence of RMNPs as the bubbles started to coarsen after 20 min. However, the incorporation of the 30 h-RMNPs improved the structure of the foam, resulting in finer bubbles with a uniform distribution. The coarsening of the bubbles began after 40 min, resulting in a uniform distribution of bubbles. The incorporation of the 6 h-RMNPs did not do well with the structure of the foam, as the foam disappeared in the first 10 min. Finally, for solutions prepared in 3% NaCl, Table 8 provides a visualization of the structure of the generated foam resulting from CO2 injection. The images show finer bubbles generated when incorporating the 30 h-RMNPs for 5 min with a uniform distribution of sizes. This structure continued for around 10 min. However, the absence of RMNPs caused a fast coarsening of the foam, starting in 5 min, when the large bubbles started to appear, and the bubble size distribution became nonuniform. In both cases, the foam completely disappeared after 15 min.

Conclusions

This study investigated the synthesis and application of red mud-derived nanoparticles (RMNPs) as a sustainable and cost-effective solution for enhancing foam stability in enhanced oil recovery (EOR) and CO2 sequestration processes. A comprehensive experimental approach was employed, involving nanoparticle production, multi-technique characterization, and evaluation of foam performance under varying salinity, pH, and gas conditions. The following are the main findings:

-

1.

The RMNPs exhibited needle and fibril shapes along with equiaxed particles with sizes of approximately 200 nm, enhancing their surface interaction.

-

2.

The optimal milling time for RMNPs synthesis was 30 h, particularly for application in saline solutions.

-

3.

Foam stability peaked at a pH of 5, whereas extreme acidic conditions (pH 3) adversely affected the stability of the RMNPs-blended solutions.

-

4.

Foam stability significantly improved with RMNPs, extending foam half-life by up to 60% and 57% in nitrogen- and CO2-based experiments, respectively.

-

5.

Foams containing the RMNPs exhibited a higher bubble count, suggesting the sustained presence of smaller bubbles and a finer bubble structure. The dominance of finer bubbles corresponds to higher foam density and better foam rheology.

-

6.

RMNPs-enhanced foams performed better at high salinity, outperforming conventional foam solutions.

The novelty of this work lies in the first-time demonstration that red mud, a widely available industrial waste, can be effectively repurposed into functional nanoparticles for foam stabilization, offering a low-cost and environmentally beneficial material for subsurface energy applications.

Future research should optimize RMNPs loading to balance foam stability, injectivity, and cost under dynamic flow conditions. Additionally, the performance of RMNPs-stabilized foam should be evaluated under simulated reservoir conditions, particularly at high temperatures and pressures, to validate its thermal resilience and structural integrity in extreme environments. These studies are vital for translating laboratory findings into practical applications, ensuring reliability and promoting waste valorization.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. The raw data files will be available upon request.

References

Mansha, M. et al. Advancements in nanoparticle-based stabilization of CO2 foam: current trends, challenges, and future prospects. J. Mol. Liq. 391, 123364 (2023).

Massarweh, O. & Abushaikha, A. S. A review of recent developments in CO2 mobility control in enhanced oil recovery. Petroleum 8, 291–317 (2022).

Al-Azani, K., Abu-Khamsin, S. A. & Sultan, A. S. Experimental study of blending CO2 with triethyl citrate for mitigating gravity override during reservoir flooding. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 46, 6787–6796 (2021).

Xue, Z., Panthi, K., Fei, Y., Johnston, K. P. & Mohanty, K. K. CO2-Soluble ionic surfactants and CO2 foams for high-temperature and high-salinity sandstone reservoirs. Energy Fuels. 29, 5750–5760 (2015).

Al-Azani, K. H., Abu-Khamsin, S. A. & Sultan, A. S. Solubilities of carbon dioxide in ethyl benzoate and triethyl citrate at high temperatures and pressures. J. Chem. Eng. Data. 65, 1857–1868 (2020).

Enick, R. M., Olsen, D. K., Ammer, J. R. & Schuller, W. Mobility and conformance control for CO2 EOR via thickeners, foams, and gels---a literature review of 40 years of research and pilot tests, in SPE Improved Oil Recovery Symposium SPE-154122-MSSociety of Petroleum Engineers, Tulsa, Oklahoma, USA, (2012). https://doi.org/10.2118/154122-MS

Moradpour, N., Yang, J. & Tsai, P. A. Liquid foam: fundamentals, rheology, and applications of foam displacement in porous structures. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 74, 101845 (2024).

Atteia, O. et al. Application of foams as a remediation and blocking agent, in Advances in the characterisation and remediation of sites contaminated with petroleum hydrocarbons (eds García-Rincón, J., Gatsios, E., Lenhard, R. J., Atekwana, E. A. & Naidu, R.) 591–622 (Springer International Publishing, Cham). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-34447-3_17. (2024).

Ibrahim, A. F. & Nasr-El-Din, H. A. CO2 Foam for enhanced oil recovery applications, in Foams-emerging technologies (eds. Xu, H., Yang, C. & Jing, D.) Ch. 7IntechOpen, Rijeka, (2019). https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.89301

Hirasaki, G. J. & Lawson, J. B. Mechanisms of foam flow in porous media: apparent viscosity in smooth capillaries. Soc. Pet. Eng. J. 25, 176–190 (1985).

Li, R. F., Yan, W., Liu, S., Hirasaki, G. J. & Miller, C. A. Foam mobility control for surfactant enhanced oil recovery. SPE J. 15, 928–942 (2010).

Srivastava, A. et al. Effects of silica nanoparticles and polymers on foam stability with sodium dodecylbenzene sulfonate in water–liquid paraffin oil emulsions at high temperatures. J. Mol. Liq. 241, 1069–1078 (2017).

Singh, R. et al. Fly ash nanoparticle-stabilized CO2-in-water foams for gas mobility control applications. SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition D011S009R005 Preprint at (2015). https://doi.org/10.2118/175057-MS

Briceño-Ahumada, Z. & Langevin, D. On the influence of surfactant on the coarsening of aqueous foams. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 244, 124–131 (2017).

Wang, J., Nguyen, A. V. & Farrokhpay, S. A critical review of the growth, drainage and collapse of foams. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 228, 55–70 (2016).

Jangir, K., Kumar, U., Suniya, N. K., Singh, N. & Parihar, K. Enhancing the aqueous foam stability using nanoparticles: a review. World J. Chem. Educ. 10, 84–90 (2022).

Pal, N., Verma, A., Ojha, K. & Mandal, A. Nanoparticle-modified gemini surfactant foams as efficient displacing fluids for enhanced oil recovery. J. Mol. Liq. 310, 113193 (2020).

Sun, L. et al. Recent advances of surfactant-stabilized N2/CO2 foams in enhanced oil recovery. Fuel 241, 83–93 (2019).

Khani, O., Mohammadi, M., Khaz’ali, A. R. & Aghdam, M. A. Effect of pH value and zeta potential on the stability of CO2 foam stabilized by SDS surfactant and SiO2, ZnO and Fe2O3 nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 15, 10302 (2025).

Sun, Y. et al. Research progress of nanoparticles enhanced carbon dioxide foam stability and assisted carbon dioxide storage: a review. Chem. Eng. J. 495, 153177 (2024).

Zhang, Y. et al. Nanoparticles as foam stabilizer: mechanism, control parameters and application in foam flooding for enhanced oil recovery. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 202, 108561 (2021).

Chaudhry, A. U. et al. Recent advancements in novel nanoparticles as foam stabilizer: prospects in EOR and CO2 sequestration. J. Mol. Liq. 407, 125209 (2024).

Xu, L. et al. Synergy of surface-treated nanoparticle and anionic-nonionic surfactant on stabilization of natural gas foams. Colloids Surf. Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 550, 176–185 (2018).

Shojaei, M. J., Osei-Bonsu, K., Richman, S., Grassia, P. & Shokri, N. Foam stability influenced by displaced fluids and by pore size of porous media. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 58, 1068–1074 (2019).

Espinosa, D., Caldelas, F., Johnston, K., Bryant, S. L. & Huh, C. Nanoparticle-stabilized supercritical CO2 foams for potential mobility control applications. SPE Improved Oil Recovery Symposium SPE-129925-MS Preprint at (2010). https://doi.org/10.2118/129925-MS

Binks, B. P. & Horozov, T. S. Aqueous foams stabilized solely by silica nanoparticles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44, 3722–3725 (2005).

Hurtado, Y., Franco, C. A., Riazi, M. & Cortés, F. B. Improving the stability of nitrogen foams using silica nanoparticles coated with polyethylene glycol. J. Mol. Liq. 300, 112256 (2020).

Hurtado, Y. et al. Effects of surface acidity and Polarity of SiO2 nanoparticles on the foam stabilization applied to natural gas flooding in tight gas-Condensate reservoirs. Energy Fuels. 32, 5824–5833 (2018).

Tang, X. C., Li, Y. Q., Liu, Z. Y. & Zhang, N. Nanoparticle-reinforced foam system for enhanced oil recovery (EOR): mechanistic review and perspective. Pet. Sci. 20, 2282–2304 (2023).

Rognmo, A. U., Horjen, H. & Fernø, M. A. Nanotechnology for improved CO2 utilization in CCS: laboratory study of CO2-foam flow and silica nanoparticle retention in porous media. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 64, 113–118 (2017).

San, J., Wang, S., Yu, J., Liu, N. & Lee, R. Nanoparticle-stabilized carbon dioxide foam used in enhanced oil recovery: effect of different ions and temperatures. SPE J. 22, 1416–1423 (2017).

Sun, J. et al. Recent advances in nanomaterial-stabilized pickering foam: mechanism, classification, properties, and applications. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 328, 103177 (2024).

Lee, D., Cho, H., Lee, J., Huh, C. & Mohanty, K. Fly Ash nanoparticles as a CO2 foam stabilizer. Powder Technol. 283, 77–84 (2015).

Cui, Z. G., Cui, C. F., Zhu, Y. & Binks, B. P. Multiple phase inversion of emulsions stabilized by in situ surface activation of CaCO3 nanoparticles via adsorption of fatty acids. Langmuir 28, 314–320 (2012).

Abdelbasir, S. M., McCourt, K. M., Lee, C. M. & Vanegas, D. C. Waste-Derived nanoparticles: synthesis approaches, environmental applications, and sustainability considerations. Front. Chem. 8, 782 (2020).

Bobicki, E. R., Liu, Q., Xu, Z. & Zeng, H. Carbon capture and storage using alkaline industrial wastes. Prog Energy Combust. Sci. 38, 302–320 (2012).

Xie, W. H., Li, H., Yang, M., He, L. N. & Li, H. R. CO2 capture and utilization with solid waste. Green. Chem. Eng. 3, 199–209 (2022).

Samal, S. Utilization of red mud as a source for metal ions—a review. Materials 14, 2211. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14092211 (2021).

Wang, C. et al. Accelerated CO2 mineralization technology using fly Ash as Raw material: recent research advances. Chem. Eng. J. 488, 150676 (2024).

Ahmed, S., Meng, T. & Taha, M. Utilization of red mud for producing a high strength binder by composition optimization and nano strengthening. Nanotechnol. Rev. 9, 396–409 (2020).

Yekeen, N. et al. A comprehensive review of experimental studies of nanoparticles-stabilized foam for enhanced oil recovery. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 164, 43–74 (2018).

Eftekhari, A. A., Krastev, R. & Farajzadeh, R. Foam stabilized by fly Ash nanoparticles for enhancing oil recovery. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 54, 12482–12491 (2015).

Guo, F., He, J., Johnson, P. A. & Aryana, S. A. Stabilization of CO2 foam using by-product fly Ash and recyclable iron oxide nanoparticles to improve carbon utilization in EOR processes. Sustain. Energy Fuels. 1, 814–822 (2017).

Wang, T., Fan, H., Yang, W. & Meng, Z. Stabilization mechanism of fly Ash three-phase foam and its sealing capacity on fractured reservoirs. Fuel 264, 116832 (2020).

Phong, G. M., Pilus, M., Mustaffa, R., Thangavel, A., Mohamed, N. M. & L. & Relationship between fly Ash nanoparticle-stabilized-foam and oil production in core displacement and simulation studies. Fuel 266, 117033 (2020).

Lv, Q., Zhou, T., Zhang, X., Guo, X. & Dong, Z. Storage of CO2 and coal fly ash using pickering foam for enhanced oil recovery. SPE International Conference on Oilfield Chemistry D021S008R004 Preprint at (2021). https://doi.org/10.2118/204330-MS

Rezaee, M., Hosseini-Nasab, S. M., Fahimpour, J. & Sharifi, M. New insight on improving foam stability and foam flooding using fly-ash in the presence of crude oil. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 214, 110534 (2022).

Li, L. Y. A study of iron mineral transformation to reduce red mud tailings. Waste Manag. 21, 525–534 (2001).

Genç-Fuhrman, H., Tjell, J. C. & McConchie, D. Adsorption of arsenic from water using activated neutralized red mud. Environ. Sci. Technol. 38, 2428–2434 (2004).

Yang, J. & Xiao, B. Development of unsintered construction materials from red mud wastes produced in the sintering alumina process. Constr. Build. Mater. 22, 2299–2307 (2008).

Agrawal, A., Sahu, K. K. & Pandey, B. D. Solid waste management in non-ferrous industries in India. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 42, 99–120 (2004).

Amritphale, S. S. & Patel, M. Utilization of red mud, fly ash for manufacturing bricks with pyrophyllite. Silic. Ind. 52, 31–35 (1987).

Ayres, R. U., Holmberg, J. & Andersson, B. Materials and the global environment: waste mining in the 21st century. MRS Bull. 26, 477–480 (2001).

Asokan, P., Saxena, M. & Asolekar, S. R. Coal combustion residues—environmental implications and recycling potentials. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 43, 239–262 (2005).

Yalçin, N. & Sevinç, V. Utilization of bauxite waste in ceramic glazes. Ceram. Int. 26, 485–493 (2000).

Sglavo, V. M. et al. Bauxite ‘red mud’ in the ceramic industry. Part 2: production of clay-based ceramics. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 20, 245–252 (2000).

Yadav, V. S. et al. Sequestration of carbon dioxide (CO2) using red mud. J. Hazard. Mater. 176, 1044–1050 (2010).

Amritphale, S. S., Anshul, A. & Chandra, N. Ramakrishnan, N. A novel process for making radiopaque materials using bauxite—red mud. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 27, 1945–1951 (2007).

Singh, M., Upadhayay, S. N. & Prasad, P. M. Preparation of iron rich cements using red mud. Cem. Concr Res. 27, 1037–1046 (1997).

AlBoraikan, R., Bageri, B. & Solling, T. I. Innovative applications of red mud: converting an environmental challenge to a drilling asset. ACS Omega. 8, 614–625 (2023).

Mahmoud, A. A. & Elkatatny, S. Using red mud to achieve sustainable well cement with balanced performance and eco-friendliness. ADIPEC https://doi.org/10.2118/222245-MS (2024). D021S051R002 Preprint at.

Çetinkaya, Z. & Kalem, V. Production of red mud based nanofibers and their potential in arsenate removal from waste water. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 43, 1079–1088 (2022).

Judith, J. V. & Vasudevan, N. Synthesis of nanomaterial from industrial waste and its application in environmental pollutant remediation. Environ. Eng. Res. 27, 200670–200672 (2022).

Deshmukh, S. et al. Red mud-reduced graphene oxide nanocomposites for the electrochemical sensing of arsenic. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 3, 4084–4090 (2020).

Sun, H. et al. Synthesis and properties of red mud-based nanoferrite clinker. J. Nanomater. 3617050 (2019).

Occhicone, A. et al. Production and characterization of nano-magnetic material through different red mud reduction processes. Mater. Chem. Phys. 328, 129950 (2024).

Roy, J. S. et al. Potential use of smartly engineered red mud nanoparticles for removal of arsenate and pathogens from drinking water. SN Appl. Sci. 2, 796 (2020).

Wang, J. et al. Preparation of nano red mud gels using red mud for the encapsulation and stabilization of arsenic in arsenic-bearing gypsum sludge. Sep. Purif. Technol. 341, 126680 (2024).

Amiri-zirtol, L. & Gholami, A. Innovative synthesis of nano-magnetic bio-organocatalysts from red mud waste for green polyhydroquinoline derivatives synthesis. Sci. Rep. 14, 26143 (2024).

Ahmed, A., Mahmoud, A. A. & Elkatatny, S. The combined effect of nanoclay powder and curing time on the properties of class G cement. Geofluids 7316335 (2023).

Amao, A. O., Al-Otaibi, B. & Al-Ramadan, K. High-resolution X-ray diffraction datasets: carbonates. Data Brief. 42, 108204 (2022).

Al-Azani, K. et al. Synergistic performance of an in-house synthesized cationic gemini surfactant for enhanced oil recovery under harsh conditions. Fuel 374, 132359 (2024).

Amani, P., Miller, R., Javadi, A. & Firouzi, M. Pickering foams and parameters influencing their characteristics. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 301, 102606 (2022).