Abstract

This study focuses on the failure analysis of hybrid woven jute and glass fiber-reinforced structural composite tubes with circumferential circular holes under quasi-static testing. Process parameters were optimized to obtain outputs including maximum stress, energy absorption, and specific energy absorption by considering hole diameter, length of the tube, and number of holes drilled as input. Results portray that the crash behaviour of the composite tubes was dependent on the number of holes drilled on the circumference and the analysis of variance results revealed that the interaction between all the process parameters affected the output variables. Energy absorption and specific energy absorption were found to be maximum for the composite tubes of 70 mm length drilled with 4 holes each of diameter 12 mm. Optimal energy absorption of hybrid composite tubes was 87.11 J and the specific energy absorption was 1.527 J/g. A regression model was also developed to predict energy absorption and specific energy absorption. Confirmation experiments portrayed an appreciable correlation between the predicted and experimental values with a less than 5 % margin of error for energy absorption and a less than 2 % margin of error for specific energy absorption. The failure mechanism of the hybrid composite tubes was analyzed using photographs of the composite tubes from which the major failure mechanism was observed to be buckling failure through longitudinal crack propagation. Such short composite columns find their applications in roll-over protection in automobiles, as retrofits in construction applications and developing modular structural designs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Structural composite columns fabricated using fiber-reinforced composites are majorly utilized in wooden columns1, civil engineering columns2,3, and automobile engineering4. Short composite columns find their application in various load bearing structures in the above applications like crash box and so on5. In terms of flexural stiffness, compressive, and tensile strength, hybrid jute fiber-reinforced polymer composites outperformed simple jute fiber composites6. It was also stated in various literature that the orientation of the jute fibers either in fiber form or in woven mat form influenced the mechanical properties much. Warp and weft orientation of the jute fibers rendered maximum mechanical properties while the unidirectional jute fiber composites had better axial mechanical properties. Besides, the orientation of fibers influenced the mechanical properties by enhancing the load bearing capacity of the fibers and the stress transfer between the various layers. It was also stated that the inner and outer laminates experienced variable stress values as far as the axial testing is considered7,8

Some studies used aluminium circular tubes and carbon fiber-reinforced polymer (FRP) composites for manufacturing hybrid composite tubes, and it was observed that the total weight of the tubes was reduced because of the effect of hybridization. Specific energy absorption (SEA) and energy absorption (EA) were evaluated for the composite tubes. Results portrayed that the SEA of the hybrid composite tubes was 38% more than the pure aluminium tubes whereas the failure mechanism of the composite tubes followed the mechanism of clean material energy absorption. The energy absorption of hybrid composite tubes fabricated in various shapes was evaluated under dynamic loading conditions both through numerical analysis and experimental methods and both the results were compared. A better correlation was observed between the two results in most cases. It was also found from various studies that the foam-filled hybrid composite tubes exhibited better energy absorption than the unfilled tubes irrespective of the fiber-reinforced composite type9,10,11,12. The glass-fiber-reinforced tube had the best SEA capabilities, with the lowest initial peak load value and the most stability in progressive crushing behaviour13,14. The energy absorption capability was purely based on the right fiber orientation. In impact crushing testing, the energy absorption capability was observed to be slightly lower than in quasi-static crushing tests9. Four different composite tubes with varying cross-sections were fabricated and subjected to crash behaviour analysis and the experimental design was carried out using the design of experiments. It was found from the results that the SEA increased with the increase in the perimeter of the composite tube and the cross-sectional parameters played an influential role in determining the energy absorption of the composite tubes15.

The reinforcements and plies stacking sequence were used in a hybrid structure that of one layer of jute fiber with one layer of glass or carbon fiber which greatly improved all crashworthiness parameters16. Corrugated aluminium alloy AA6060 was used for making taper cylindrical tubes and was subjected to numerical analysis for evaluating the SEA characteristics. It was found from the results that the rate of corrugations decreased the initial peak loads at higher wavelengths17. The crash behaviour of single and bi-tubal polygonal-shaped aluminum composite tubes was investigated using tubes filled with foams, with a foam density of 0.38 g/cc. This resulted in a high average crushing force. The crosshead speed during testing was changed between 5, 15, and 25 m/s. When compared with the numerical findings, the SEA was reported to be higher at 25 m/s crosshead velocity. Lateral loading conditions rendered lower energy absorption when compared with the axial loading conditions18,19,20.

Conical-shaped tubes of lengths 200 and 136 mm with varying thicknesses along the inner diameter in the bigger end were prepared by some researchers. It was found that the 200 mm length tube with 1.90 mm thickness absorbed a maximum energy of 14 kJ. From the numerical simulation results of crashworthiness tests, the tube with 1.57 mm thickness was found to possess maximum value21. In some other research works, a carbon fiber mat was wound around a aluminium circular tube and subjected to three-point flexural tests. It exhibited a quasi-static crash value of 17 kN. Crashworthiness indicators were improved by increasing the length of the composite tube from 150 to 300 mm. At a carbon fiber woven mat orientation of − 45°/45°, the greatest crashworthiness indicators were discovered. Using the discrete optimization technique, the tube length and orientation angle (optimum) was obtained as 225 mm and 45º respectively22. A foam-filled aluminium alloy tube wound with a carbon fiber hybrid epoxy composite was used to create the hybrid sandwich tube. The SEA and mean effective force were found highest value in the sandwich tube with a CFRP tube outside23. Some aluminium-based short composite square columns were studied with varying thickness and concluded that the foil thickness was directly proportional to crash force and maximum energy absorption24,25. In some other research works, short composite columns such as bi-tubular columns and sandwich columns were fabricated and concluded that hexagonal shaped columns and metal/fiber interface exhibited higher crash force and impact strength26,27,28. Some researchers fabricated lightweight cylindrical composite tubes with glass and kenaf fibers for aeronautical and automobile applications. Their crashworthiness behaviour suggested that the replacement of one kenaf layer with a glass layer enhanced the crash resistance of the composite tubes significantly. It was also stated that the reduction of loading rate decreased the crashworthiness behaviour of the composite tubes, and the tubes filled with foams exhibited higher energy absorption and peak force when compared with the unfilled tubes29,30,31.

From all the above discussions, it could be stated that the composite tubes were fabricated in various shapes such as cylindrical, polygonal, and bi-tubular with different materials including steel, glass, and aluminium-based polymer composites, and were subjected to quasi-static compression tests to evaluate the crashworthiness behaviour. The crash behaviors were studied using various thicknesses, diameters, and testing speeds. However, jute-based and hybrid composite tubes with natural-synthetic fiber composites were the least studied in the literature. Alongside this, the hybrid fiber-reinforced composite tube with a circumferential drilled hole is yet to be investigated, and the optimization of crash behaviour has not yet been evaluated by modifying design variables. Accordingly, the goal of the current work is to develop jute and glass fiber woven mat reinforced epoxy composite tubes with circumferential drilled holes with various drill hole diameters (D), tube lengths (L), and the number of drilled holes (H). The tubes were subjected to uniaxial static compression and the energy absorption (EA) and specific energy absorption (SEA) were determined. Optimization is also carried out to optimize the process parameters for begetting maximum EA and SEA values.

Materials and experiments

Materials used

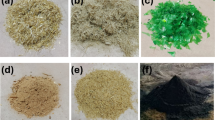

A bi-directional woven jute yarn mat with 700 mm width, 1 ± 0.15 mm thickness, 8 yarn/cm density in weft and warp directions and 1250 mm length was acquired from Parthipan Weaving Industry in Erode, Tamil Nadu, India (Fig. 1a). Figure 1b shows the Woven roving glass mat (0°/90°/45° orientations) with 400 GSM density, 1250 mm width, 0.4 mm thickness and 625 mm length from Covai Seenu & Company, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India. It was stated in the earlier works that these orientations for natural and synthetic fibers rendered better mechanical properties32,33

Commercially used Epoxy resin LY550 and hardener HY550 were purchased from Covai Seenu and Company, Coimbatore. Table 1 enlists the various properties of epoxy resin.

Hybrid composite tube fabrication

The Jute fiber mat, glass fiber mat, and epoxy resin were used to fabricate the hybrid fiber-reinforced polymer tube with 40% volume fraction of fibers. The epoxy resin and hardener were first carefully mixed at a 10:1 ratio. The wooden table was covered with a plastic cover and the jute and glass fiber mats were placed one above the other after coating both sides of the mat. The process was repeated for the remaining glass and jute fiber mats until the required number of layers were stacked. A total of six layers with glass layer sandwiched by jute layers were used to attain a composite tube of 3 mm uniform wall thickness. A wooden roller was used to make the composite tube. A polyvinylchloride (PVC) tube of 70 mm external diameter was inserted into the wooden roller and tightly clamped. The releasing agent was applied on the PVC tube and the wet fiber mat was placed on the PVC tube. Following that, the two halves of the PVC tube were covered with the wet mats on the wooden roller, and using a simple C-clamping approach, the composite mixture was tightly clamped. The resin leak was arrested by using the tick tabs on both corners of the base PVC tube and the curing time was maintained at 8 h for all the composite tubes. Figure 2 shows the fabricated hybrid composite tubes after removing them from the dies and sizing them as per the required lengths. The preformed composite tubes had a 300 mm overall length, 70 mm and 76 mm as inner and outer diameters respectively. Different hybrid composite tube lengths of 70 mm, 140 mm and 210 mm were developed based on aspect ratio ranging in between 1 and 3 respectively.

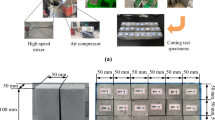

The circumferential sides of the fabricated composite tubes were drilled with holes of varying diameters and numbers. Drill hole diameters (d) were varied between 8, 10, and 12 mm, as well as drill hole placements on the various sides of the tubes, the number of the holes on the tubes are 2, 4, and 6 respectively. The dimensions of the composite tubes, the hole dimensions and the hole positions were selected based on the real-world application and the values were suitably scaled down as per the availability of the resources. Figure 3 depicts the modeled schematic of the various positions along the circumference of the composite tubes35 .

Quasi-static compression test

The uniaxial quasi-static compression test was performed in a servo universal testing machine (Model: TUF-C-1000), as shown in Fig. 4, with 1000 kN capacity. The compression tests were carried out at room temperature with a crosshead speed of 10 mm/min21. A total of 2 specimens were fabricated for each configuration and tests were carried out. During the tests, the linear crash compressive displacement of the composite tubes was measured using a rotary encoder. Test data including the load and displacement from a load cell and an encoder respectively were obtained using a data acquisition system. These values were entered into a data gathering system, and a load versus displacement graph was plotted.

The crashworthiness performance of the composite tubes was calculated using the acquired data. The EA and SEA values were calculated from the acquired peak crash loads. As depicted in Fig. 5, the zone in which the maximum load (Pmax) reaches is the pre-crush zone (i.e., the first half of the curve). The post-crush zone is the second section. The compaction zone is the third zone. From the load versus displacement curves of the composite tubes containing circumferential drilled holes, the pre-crush zone was obtained with a maximum load of Pmax and a single falling curve post-crush zone.

The following equations are used to determine crashworthiness indicators35. The area under the displacement curve was considered while calculating the EA values and the mass of the tubes were included to calculate the SEA values.

-

The peak load (Pmax) in kN was taken from the above curve.

-

The crash stress (σ) was calculated using the following Eq. 1.

$$\upsigma =\frac{{P}_{max}}{{A}_{0}-{A}_{i}}$$(1)where, Ao = Area (outside diameter).Ai = Area (inside diameter)

-

Energy absorption (EA) can be calculated using the following equation

$$\text{EA}= \frac{1}{2}{P}_{max}\delta \left(l\right)$$(2)where, \(\delta\)(l) = Displacement during the crash (m).

-

Specific Energy absorption (SEA) can be calculated using the following Eq. 3.

$$\text{SEA}=\frac{EA}{m}(J/g)$$(3)m = mass of the hybrid composite tube (g).

Optimization of design variables

The independent variables for the composite circular tube’s crashworthiness study were chosen based on process understanding and are enlisted in Table 2. The chosen process variables were the length of the composite tube (L), the diameter of the hole (d), and the number of circumferential holes made (n) and these parameters were expected to have a direct impact on the crashworthiness behaviour of the composite tube. Taguchi’s design of experiments (DOE) was adopted and the control variables were investigated for their interaction effects also. The experimental design was carried out using an L27 orthogonal array and crashworthiness tests were conducted on 27 different composite tubes.

Results and discussion

Quasistatic load versus displacement

Figure 6 depicts the load vs. displacement curves of the quasi-static compression test carried out on the hybrid composite tubes. The progression of these curves exhibited only one peak owing to the availability of the holes drilled on the hybrid composite tubes. It could be observed from the compression peaks that the crash load and displacement varied linearly. Circumference of the composite tubes experienced major stress concentration due to the circumferential holes, with maximal stress created around the perimeter of the holes as the load gradually applied. For the composite tube of 70 mm length, the Pmax value was obtained for the tube with 6 number of holes of 8 mm diameter whereas for the composite tubes of 140 mm length, the peak load was obtained for the tube with 4 and 2 holes of 10 mm and 12 mm respectively. In the case of the composite tube with 210 mm length, the tube with 4 holes of 10 mm diameter could bear the maximum compressive load. The load-carrying capacity of the tube decreased as the length was increased, and the displacement increased from 6.25 to 7.49 mm for the tube of length 70 mm and 140 mm respectively and this is governed by the diameter of the drilled hole. These curves experience a fall owing to the initiation of material fracture demonstrating a steady-state crash.

Table 3 shows the results of quasi-static compression tests. The table displays the variables like composite tube length, the diameter of the drilled hole (d), and the number of circumferential holes (H). The inner diameter of the tubes was constantly kept at 70 mm. Specific energy absorption (SEA) and energy absorption (EA) are the measured output variables of the compression test.

Influence of process variables on energy absorption

Figure 7 displays the variation of EA values with the n, L and d values for the composite tubes. It could be observed from the values that the EA value of the 70 mm composite tube increases with the ‘n’ and ‘d’ values. It could be possibly due to the fracture initiation in the middle and uniform propagation of the same throughout the tube holes. The highest value of EA was exhibited by composite tubes with four 8 mm drilled holes owing to the uniform crack propagation and progressive tube failure. The EA values reduced with the increase in number of drilled holes beyond four which could be due to the non-propagation of the failure crack linearly in between the drilled holes. For the composite tube of length 70 mm, the EA values increased by 52.4% and decreased by 63.45% for four and six holes respectively with 8 mm diameter. In the case of 10 mm diameter holes, the values increased by 58% and decreased by 59.8% for four and six holes respectively while the EA values decreased by 37% and increased by 18.4% for four and six holes respectively with 12 mm hole diameter.

In the case of the 140 mm composite tube, the stress uniformly distributed around the drilled holes and the fracture failure was observed to be completely linear leading to the higher EA for the tubes with four and six 8 mm diameter holes. However, the lack of linear failure, the EA is found to be very low at four holes. In the case of an 8 mm diameter hole, the EA value increased by 36.6% and 31.2% for the composite tubes with four and six holes respectively while for a 10 mm diameter hole, the values increased by 13.7% and 35.1% respectively. An increase of 7% EA and a decrease of 25.6% was witnessed for four and six 12 mm diameter holes respectively.

For the 210 mm composite tube of, the tube with a 10 mm diameter hole and six drill holes has the highest EA. A uniform stress distribution in the composite tube with a 10 mm diameter hole was observed and failure by fracture was linear when compared with the composite tube with an 8 mm diameter hole. The EA is found to be very low for all the composite tubes with 8 mm diameter holes due to the non-uniform failure and high stress concentration was also observed when the drill diameter is increased. For a 210 mm specimen length, an increase of -0.18% and 10.8% for an 8 mm diameter hole, 29.7% and 0.8% for a 10 mm diameter hole, and 4.5% and -10.2% for a 12 mm diameter hole with four and six holes respectively. It could also be noted that the EA for all composite tubes with six holes was found to be lesser for higher diameters except for 8 mm and 10 mm diameter holes in 70 mm tube lengths. This could be attributed to the sharing of the stress concentration zones between the holes. Overall, from all the test results, it could be noted that the maximum EA was obtained for the composite tube with a length of 70 mm containing six holes of diameter 10 mm despite the growth in EA. Owing to the lower stress concentrations around the drilled holes, the EA was lower for all other tubes.

Influence of process variables on specific energy absorption

Figure 8 displays the variation of specific energy absorption (SEA) with the number of circumferential holes, the length of the tube, and the diameter of the drilled hole. The SEA was found to increase with the number of drilled holes of 8 mm and 10 mm diameter while it decreased for the composites with 12 mm diameter holes as observed in Fig. 8a. This could be due to the circumferential failure of composite tubes and the propagation of the fracture cracks in between the drilled holes which resulted in increased stress concentration in the vicinity of the holes. From Fig. 8a, it could also be noted that the SEA was higher for the tubes containing six holes (for 8 mm and 10 mm diameter holes) which could be due to the central position of holes subtending 90 º between them and the linear crack propagation between the holes. The value of SEA decreased for the composite tube with six holes of 12 mm diameter. While considering the increase in SEA values between the two, four, and six holes, all the composite tubes with any length and any diameter hole witnessed an increase in SEA value where the least increment was noted to be for the composite tube with six holes of 12 mm diameter when compared with two holes of the same diameter.

In Fig. 8b, due to the gradual fracture failure of the tubes with 140 mm length, the 2,4 and 6-hole tubes have a gradual increase in SEA values. For the composite tubes with four holes, fracture propagation was observed in between the drilled holes which minimized the value of SEA. Increased hole diameter lowered the SEA at 12 mm drill diameter owing to repeated crack propagation in the composite tubes. The highest value of SEA was exhibited by the composite tube with 6 holes each of diameter 10 mm. For 140 mm composite tube, the SEA value increased by 79% and 76% for 8 mm diameter holes and by 32% and 126% for 10 mm diameter holes for the tubes with four and six holes respectively. In the case of a 12 mm diameter hole, the SEA value was found to be increased by 6.8% and decreased by 40% for the tube with four and six holes respectively.

As far as the 210 mm composite tubes are concerned, the value of SEA was found to be maximum for the tubes with 6 holes of 8 mm drill diameter. On the other hand, unlike the tubes with 8 mm diameter holes, since the crack propagation occurred near loading areas, the tubes drilled with 10 mm and 12 mm diameter holes exhibited lower SEA values. As a result, compressive stress was distributed evenly throughout the composite tube and resulted in lower stress levels around the drilled holes. However, if the hole size was increased to 12 mm, the results did not improve as much as increasing the hole size for 10 mm. In the case of 210 mm composite tube, the SEA was found to be increased by 6% and 23% for 8 mm diameter holes and by 41.1% and 16.7% for 10 mm diameter holes for the tubes with four and six holes respectively. In the case of a 12 mm diameter hole, the SEA value was found to be increased by 13% and decreased by 2.1% for the tube with four and six holes respectively.

From Fig. 8d-f, it could be observed that the SEA reduced when two additional holes were drilled along the entire length of the composite tube. The SEA values portrayed that the occurrence of multiple fractures along the longitudinal side and propagation of the crack in between the holes due to higher stress concentration levels decreased the values for the composite tubes when the diameter of the drilled hole increased beyond 8 mm. Figure 8e, f shows that there was a drastic change in the value of SEA when the number of circumferential holes and their position was modified. The variation of SEA was governed by the increase in diameter of the drill rather than increasing the number of drilled holes on the composite tubes. It was also noted that the increase in length of the composite tube decreased the value of SEA owing to the non-uniform crack propagation amidst the drilled holes. Overall, the composite tube with 70 mm length and six drilled holes each of 10 mm diameter exhibited the highest value of SEA due to the uniform propagation of the fracture crack amidst the drilled holes.

For two drilled holes, the increase in SEA was about 14.7% and 88.52% between 10 and 12 mm hole diameter respectively at 70 mm length, 26.5% and 13.3% between 10 and 12 mm hole diameter at 140 mm length, and a decrease of 19.4% and 12.2% between 10 and 12 mm hole diameter at 210 mm length. For four drilled holes, an increase in SEA value of 83.8% and 98% was observed between 10 and 12 mm diameter holes at a length of 70 mm, 6% decrease and 60.7% increase between 10 and 12 mm respectively at 140 mm tube length, and an increase of 7.3% and a decrease of 17.6% was observed respectively for 210 mm composite tube length. For six drilled holes, the SEA values decreased by 66.3% and 39.7% at a length of 70 mm, a decrease of 27.1% and 25.4% for 10 mm and 12 mm diameter holes respectively at 140 mm, and 34.9% and 29.7% for 10 mm and 12 mm diameter holes respectively at 210 mm. all the above percentage variations were calculated by taking the SEA value of 8 mm diameter hole as a reference.

Discussion of failure mechanism

A structure can be termed as a proper crashworthy structure if it can absorb the maximum amount of crash energy with a controlled design of the structure and this can be achieved by incorporating novel structural alterations and design of the composite tubes. Accordingly, drilled holes were introduced in the current composite tubes as a new design concept. The crashworthiness of the jute/glass hybrid composite tubes was considered by assuming the tube as an energy-absorbing structure for which the understanding of the failure mechanism of the structure is inevitable. The load changes as a displacement decreased for the tube for specimens that had undergone buckling failure, resulting in continuous retardation35,36, and a similar progressive failure was detailed for the carbon fiber tube in the previous studies16,23. Buckling failure was also termed catastrophic failure in some studies. The tube buckles at first, and then catastrophic collapse occurs when the tube reaches its maximum peak stress. During tests including various tube lengths, the diameter, and the hole numbers, these failure modes were observed in jute/glass mat hybrid fiber composite tubes37,38.

Figures 9, 10, 11 shows crushed composite tubes before and after crash failure in buckling mode. In Fig. 9a1, under quasi-static compressive strain, an early crack induced in the composite tube with an 8 mm diameter hole, and buckling began at the later stage in the composite tubes in which the drilled holes were at an angle of 180°. When the number of drilled holes increased to four and the angle between them was changed to 90° (as seen in Fig. 9a2), the buckling crack propagation initiated between the drilled holes and the failure mode of the composite tubes were observed to be gradual buckling failure. As shown in Fig. 9a3, when the number of holes was increased to six and by modifying the angular position of the holes with an angle of 45 º between them, the crack propagation occurred at the top and bottom of the hole and a rapid buckling failure occurred owing to the increase in the n value. At 140 mm composite tube length, the drilled hole was positioned at the center of the tube, and the angular distance between the holes was 180º (Fig. 9b2), the initial fracture spread amidst the tube holes, and the crack propagation occurred throughout tube specimen owing to the failure by rapid buckling. Beyond the n value of 6, a similar problem occurred (Fig. 9b3) and the buckling initiated from the middle of the composite tube. The formation of cracks between the holes at 4 holes (Fig. 9b2), the buckling and catastrophic collapse did not occur. The initial fracture propagation for the composite tube with 210 mm length and six holes with 8 mm diameter was found at the center, and the failure crack traveled to another hole due to propagative catastrophic failure. Buckling failure occurred at the tube specimen with 2 and 4 holes (Fig. 9c1–c3 when the composite tube reached its maximum compressive load.

Crash behaviour of hybrid composite tubes with 8 mm drilled holes (a1) 70 mm length with 2 holes, (a2) 70 mm length with 4 holes, (a3) 70 mm length with 6 holes, (b1) 140 mm length with 2 holes, (b2) 140 mm length with 4 holes, (b3) 140 mm length with 6 holes, (c1) 210 mm length with 2 holes, (c2) 210 mm length with 4 holes, (c3) 210 mm length with 6 holes.

Crash behaviour of hybrid composite tubes with 10 mm drilled holes (a1) 70 mm length with 2 holes, (a2) 70 mm length with 4 holes, (a3) 70 mm length with 6 holes, (b1) 140 mm length with 2 holes, (b2) 140 mm length with 4 holes, (b3) 140 mm length with 6 holes, (c1) 210 mm length with 2 holes, (c2) 210 mm length with 4 holes, (c3) 210 mm length with 6 holes.

Crash behaviour of hybrid composite tubes with 12 mm drilled holes (a1) 70 mm length with 2 holes, (a2) 70 mm length with 4 holes, (a3) 70 mm length with 6 holes, (b1) 140 mm length with 2 holes, (b2) 140 mm length with 4 holes, (b3) 140 mm length with 6 holes, (c1) 210 mm length with 2 holes, (c2) 210 mm length with 4 holes, (c3) 210 mm length with 6 holes.

Figure 10 depicts the quasi-static compressive loading of composite tubes with 10 mm drilled holes. Figure 10(a1) depicts tube buckling due to rapid fracture propagation in the tube’s center and in between the circumferential holes. However, when the number of drilled holes on the tube’s circumference was increased (Fig. 10a2), the crack initiation and propagation also expedited, resulting in catastrophic collapse once peck crank force was reached. In the case of six drilled holes at an angle of 45º between them (Fig. 10a3), the crack began in the center hole and spread to the bottom through the holes, eventually resulting in the tube collapsing. As shown in Fig. 10b1, b2, for the composite tubes of 140 mm length containing two and four drilled holes, the initial fracture crack development was at the tube center, and the propagation was along the vertical axis of the holes resulting in a gradual buckling failure. Figure 10b3 depicts a catastrophic tube collapse that occurs quickly. For 210 mm tubes with 4 and 6 holes, failure occurred in a similar way (Fig. 10c1, c2). For the composite tube with a higher length and two angular holes with 180 º between them (Fig. 10c3), the failure occurred in the tube center, with no buckling failure visible throughout the tube. Figure 11 depicts the mechanism of failure of the composite tube with 12 mm diameter drilled holes. As seen in Fig. 11a1, the initial fracture propagated towards the center of the tube and through the gap between the drilled holes, progressing through the longitudinal side owing to higher stress concentration in the hole vicinity and higher drill diameters which reduced the rate of the buckling failure. The fracture was propagated from the center of the hole in the case of composite tubes with four and six drilled holes and due to the presence of a higher quantity of holes and their angular location, the composite tubes did not experience the buckling failure which can be seen in Fig. 11a2, a3. Numerous fractures occurred in the surroundings of the tube due to increased stress concentration as witnessed in Fig. 11b1–b3, c1–c3.

Optimization of design variables

The following sections deal with the optimization of considered process parameters like hole diameter, number of holes and tube length for obtaining maximum energy absorption and maximum specific energy absorption. Taguchi’s DOE and Analyss of Variance (ANOVA) are used for the experimental design and optimization of the design variables.

Effect of process variables on EA

Table 4 shows the S/N ratio for all the conducted experiments and Table 5 shows the S/N ratio for EA. The higher the S/N ratio for a process parameter, the better the dimensions. The tube length appears to be the most impacted characteristic for EA. The parametric levels rendering the maximum value of EA have been taken as the optimal parameters. The EA of the composite tubes was highly governed by the L value followed by the n value. However, the impact of d value on EA was minimal. To predict the process parameters by developing a non-linear regression model, main effects and interaction plots were made based on the S/N ratio of the EA by considering the ‘larger the better’ objective function.

Figure 12 depict the main effect and interaction plot for the S/N ratio values of EA. The values of EA were found to vary with the design parameters and the center line in Fig. 12 denotes the average value of EA. Since the ‘larger the better’ objective function has been chosen, the optimal values from the main effects plot were chosen from the highest point of the curves. By changing the diameter of the holes, the variation of the EA values was found to be linear while the tube length had the most significant impact on the output. From the interaction plot, the interaction between the design variables was deduced. If the interaction values are greater, the chosen parameters would have higher significance. From both curves, the best control parameter value was determined to be the composite tube with 70 mm length and drilled with four holes of 12 mm diameter. As observed from Fig. 11a2, the tube collapse was initiated at the point of loading, and no catastrophic failure was observed. Hence it could be inferred that the composite tube length is directly proportional to the value of EA.

Table 6 shows the analysis of variance (ANOVA) values for EA. It displays the individual and interaction effects of all factors, as well as the proportion of the control parameter’s contribution to EA. The analysis was carried out with a 95% level of confidence34. As a result, the criteria on EA for crash tube creation are quite important. The number of circumferential holes had a higher influence on EA with a contribution percentage (Pc) of 3.49. However, the interaction between the d value and the n value was found to have the greatest influence on EA followed by the second-order interaction between the n value and the d value. Though the L value individually has the least contribution, its interaction with other process parameters had a greater influence on the EA of the composite tube. On the whole, the number of holes influenced the energy absorption of the short composite tubes. The increase in length increased the energy absorption while the a large increase in hole diameter increased the energy absorption.

Effect of process variables on SEA

Table 7 shows the S/N ratio value for SEA. The tube length appears to be the most impactful parameter for SEA. Like EA, SEA was also highly influenced by the L value followed by the n value while d value had the least influence.

Figure 13 depict the main effect and interaction plot for the S/N ratio values of SEA. The values of SEA were found to vary with the design parameters. The variations in the levels of n, d and L values were found to be linear with the variation of SEA, and a higher variation of SEA was observed in between the composite tube lengths of 70 mm and 140 mm. The interaction of the design variables with SEA values depicts the following: the greater the value, the better the control parameters are chosen. The optimal values were deduced as the composite tube length of 70 mm with six circumferential holes, each of 10 mm diameter.

Table 8 shows the results of the ANOVA for SEA. It displays the individual and interaction effects of all factors, as well as the proportion of the control parameter’s contribution to EA. The analysis was carried out with a 95% level of confidence34. Individually, L value greatly influenced the SEA with the highest Pc. The interaction between the L value and the n value had a greater influence on SEA followed by the interaction between all the considered process variables like L, d and n.

Regression equation and confirmation test

MINITAB 19 was used to develop the regression model and carry out the optimization processes. The relationship between the chosen process variable and the response variable was demonstrated by the developed model. The following is the regression model for EA and SEA for hybrid composite tubes.

Equation (4) demonstrates that the EA linked with the design variables is positive, suggesting that the EA grows as the control parameters are increased. Equation (5) demonstrates that when the L value and the n value increase, the value of SEA also increases, but it decreases the diameter of the hole. Table 9 shows the parameters used in the optimization process to calculate the error between experimental and predicted results, as well as the confirmation test. The composite tubes were developed based on a confirmation test in the optimization process and the quasi-static compressive test was performed based on the table data. Table 10 shows the percentage error predicated between the experimental results and regression values. The predicated error for EA and SEA were in the normal level. The parameters shown in Table 10 are best suited for making the hybrid fiber reinforced composite tubes.

Conclusions

The glass and jute fiber woven mat hybrid epoxy composite tubes were fabricated using hand layup technique followed by rolling . The quasi-static compressive tests was performed on the tubes and predicted the crashworthiness indicators with the effect of introducing the drilled holes of different diameters and positions.

-

The energy absorption of the composite tubes was found to increase with the number of circumferential holes and the maximum value was attained for the composite tube of length 70 mm and 140 mm with four holes of diameter 12 mm. When the length of the composite tube increased beyond 140 mm, the energy absorption decreased due to the development of multiple non-linear cracks.

-

The specific energy absorption value increased with the number of circumferential holes and the diameter of the hole, and the maximum value was attained for the composite tube of length 70 mm with four holes of diameter 10 mm. During the test, only a few samples exhibited catastrophic and buckling failure patterns.

-

Optimization results portray the number of drill holes had a greater influence on the energy absorption of the tubes, followed by the composite tube length and diameter of the holes. The tube length had greater influence on specific energy absorption. In the case of energy absorption, the composite tube of length 70 mm with four holes each of 12 mm diameter at 90 º angular distance was the optimal combination whereas for the specific energy absorption, the composite tube with 70 mm length having four holes each of 10 mm diameter with 180 º angular distance was the optimal combination.

-

Confirmation tests portrayed a better correlation between the experimental and predicted values and the error values was well within the range of 5 % significant limit. From the experiments, it was found that the composite tubes mostly failed due to crack initiation and propagation between the holes, and buckling and brittle failure were the predominant failure modes.

-

Though the composite tubes were analyzed using simplified optimization techniques, the results portray the application of the developed composite tubes to medium-load structural applications. However, a comprehensive analysis of the process parameters can be made using some modern tools and the composite tubes can be developed based on the obtained results. Such composite tubes can find their application in diverse components including automobile crash boxes, bumpers, energy absorption buffers in railway coaches, seismic dampers for buildings and blast protection panels for unmanned vehicles.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Cheshmeh, E., Karbon, M., Eyvazian, A., Jung, D.W., Habibi, M., & Safarpour, M. Buckling and vibration analysis of FG-CNTRC plate subjected to thermo-mechanical load based on higher order shear deformation theory. Mech. Based Design Struct. Mach. pp. 1–24 (2020)

Nikkhah, H., Baroutaji, A. & Olabi, A. G. Crashworthiness design and optimisation of windowed tubes under axial impact loading. Thin-Walled Struct. 142, 132–148 (2019).

Fox, T. A. Flow visualization at the center of a cross composed of tubes. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 11(2), 160–162 (1990).

Chen, Z. H., Rong, B. & Fafitis, A. Axial compression stability of a crisscross section column composed of concrete-filled square steel tubes. J. Mech. Mater. Struct. 4(10), 1787–1799 (2010).

Zhang, L. et al. Crashworthiness of GFRP/aluminum hybrid square tubes under quasi-static compression and single/repeated impact. E-Polymers 24(1), 20240101 (2024).

Gogna, E., Kumar, R., Sahoo, A.K., & Panda, A. A comprehensive review on jute fiber reinforced composites. Adv. Indust. Product. Eng. pp. 459–467 (2019)

Bhuiyan, A. A. H., Hossain, M. F., Rana, M. S. & Ferdous, M. S. Impact of fiber orientations, stacking sequences and ageing on mechanical properties of woven jute-kevlar hybrid composites. Results Mater. 20, 100477 (2023).

Sahu, D. P. & Mohanty, S. C. Static and dynamic analysis of polyethylene terephthalate foam core and different natural fiber-reinforced laminated composite-based sandwich plates through experimental and numerical simulation. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 32(13), 3066–3085 (2025).

Alkhatib, S. E., Tarlochan, F. & Eyvazian, A. Collapse behavior of thin-walled corrugated tapered tubes. Eng. Struct. 150, 674–692 (2017).

Zhou, J. K., Lin, W. K., Guo, S. X., Zeng, J. J. & Bai, Y. L. Behavior of FRP-confined FRP spiral reinforced concrete square columns (FCFRCs) under axial compression. J. Build. Eng. 45, 103452 (2022).

Mohamed, A. S. et al. Experimental analysis of additively manufactured thin-walled heat-treated circular tubes with slits using AlSi10Mg alloy by quasi-static axial crushing test. Thin-Walled Struct. 138, 404–414 (2019).

Magliaro, J., Mohammadkhani, P., Rahimidehgolan, F., Altenhof, W. & Alpas, A. T. Influence of extruded tubing and foam-filler material pairing on the energy absorption of composite AA6061/PVC structures. Materials 16(18), 6282 (2023).

Bakar, M. S. A., Salit, M. S., Yusoff, M. Z. M., Zainudin, E. S. & Ya, H. H. The crashworthiness performance of stacking sequence on filament wound hybrid composite energy absorption tube subjected to quasi-static compression load. J. Market. Res. 9(1), 654–666 (2020).

Gao, H., Wang, L., Chen, B., & Yan, M. Axial compressive behavior of GFRP tube-reinforced concrete-steel double skin tubular columns. J. Build. Eng. p. 106973 (2023)

Zhang, H. & Zhang, X. Crashworthiness performance of conical tubes with nonlinear thickness distribution. Thin-Walled Struct. 99, 35–44 (2016).

Attia, M. A., Abd-El-Baky, M. A., Hassan, M. A., SebEAy, T. A. & Mahdi, E. Crashworthiness characteristics of carbon–jute–glass reinforced epoxy composite circular tubes. Polym. Compos. 39(S4), 2245–2261 (2018).

Sun, G., Wang, Z., Yu, H., Gong, Z. & Li, Q. Experimental and numerical investigation into the crashworthiness of metal-foam-composite hybrid structures. Compos. Struct. 209, 535–547 (2019).

Mert, S. K., Demiral, M., Altin, M., Acar, E. & Güler, M. A. Experimental and numerical investigation on the crashworthiness optimization of thin-walled aluminum tubes considering damage criteria. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 43(2), 113 (2021).

Sahu, D. P., Das, R., Prusty, J. K. & Mohanty, S. C. Frequency analysis of skew sandwich plates with polyethylene terephthalate foam-core and carbon/basalt fiber-reinforced hybrid face layers using ANFIS model and experimental validation. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. https://doi.org/10.1080/15376494.2024.2438910 (2024).

Praveen Kumar, A., & Vetrivel Sezhian, M. Lateral crashworthiness performance of a novel hybrid composite bi-tubular structures—an experimental study. In Recent Advances in Materials Technologies: Select Proceedings of ICEMT 2021 (pp. 407–414). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore. (2022)

Estrada, Q. et al. Effect of radial clearance and holes as crush initiators on the crashworthiness performance of bi-tubular profiles. Thin-Walled Struct. 140, 43–59 (2019).

Bambach, M. R. Experiments and crushing mechanism analysis of hybrid square metal tubes with filament wound CFRP. Compos C Open Access 6, 100194 (2021).

Yalçın, M.M., & İskender Özsoy, M. Lateral compression behavior of expanded polypropylene foam-filled carbon fiber reinforced polymer and aluminum/carbon fiber reinforced polymer composite tubes: an experimental study. J. Reinforced Plast. Compos. (2023)

Gao, X., Zhang, Z., Xu, J. & Su, S. Mechanical behavior of CFRP confined seawater sea-sand recycled concrete-filled circular aluminum-alloy tube columns under axial compression. Constr. Build. Mater. 397, 132355 (2023).

Kumar, A. P. & Sundaram, M. S. An axial crushing characteristics of hybrid kenaf/glass fabric wrapped aluminium capped tubes under static loading. Int. J. Mech. Product. Eng. Res. Dev. 8(6), 201–206 (2018).

Bhardawaj, S., Sharma, R.C., & Sharma, S.K. Development and advancement in the wheel-rail rolling contact mechanics. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. (2019)

Rajak, D. K., Mahajan, N. N. & Linul, E. Crashworthiness performance and microstructural characteristics of foam-filled thin-walled tubes under diverse strain rate. J. Alloy. Compd. 775, 675–689 (2019).

Wei, Y., Chen, S., Tang, S., Zheng, K. & Wang, J. Mechanical behavior of bamboo composite tubes under axial compression. Constr. Build. Mater. 339, 127681 (2022).

Supian, A. B. M. et al. Crashworthiness response of filament wound kenaf/glass fibre-reinforced epoxy composite tubes with influence of stacking sequence under intermediate-velocity impact load. Fibers Polym. 23, 223–233 (2021).

Kumar, A. P., Shunmugasundaram, M., Sivasankar, S. & Sankar, L. P. Numerical analysis on the axial deformation and energy absorption behaviour of tri-tubular structures. Mater. Today Proc. 27, 866–870 (2020).

Rufini, R., Di Pietro, O. & Di Schino, A. Predictive simulation of plastic processing of welded stainless steel pipes. Metals 8(7), 519 (2018).

Gairola, S., Chaitanya, S., Kaushik, D., Sinha, S. & Singh, I. Static and dynamic mechanical behavior of intra-hybrid jute/sisal-reinforced polypropylene composites: effect of stacking sequence. Polym. Compos. 45(8), 7049–7058 (2024).

Namer, N. S. M. & Ali, A. J. H. Mechanical properties of multi-layer woven E-glass/epoxy in variable fiber-mat directions. J. Tech. 5(2), 52–60 (2023).

Patel, R. V., Yadav, A. & Winczek, J. Physical, mechanical, and thermal properties of natural fiber-reinforced epoxy composites for construction and automotive applications. Appl. Sci. 13(8), 5126 (2023).

Sathishkumar, T. P., Satheeshkumar, S., Bhuvaneshkumar, K., Sanjay, M. R. & Siengchin, S. Crashworthiness characterization of jute fiber woven mat reinforced epoxy composite tube for structural application using Taguchi’s method. Int. J. Crashworthiness 27(5), 1351–1367 (2022).

Eyvazian, A., Tran, T. N. & Hamouda, A. M. Experimental and theoretical studies on axially crushed corrugated metal tubes. Int. J. Non-Linear Mech. 101, 86–94 (2018).

Ma, Q. et al. Axial and radial crushing behaviour of thin-walled carbon fiber-reinforced polymer tubes fabricated by the real-time winding angle measurement system. Forces Mech. 10, 100170 (2023).

Praveen Kumar, A. & Sathish Kumar, M. Deformation characteristics of press-formed cylindrical tubes with shallow and hemispherical caps for frontal crash protective structures. Int. J. Protect. Struct. https://doi.org/10.1177/2041419619830701 (2019).

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors equally contributed in bringing up this manuscript. TPS, SS – Data collection ,Writing: Original draft, Validation; LRK, SS – Writing: Original Draft, Reviewing and Editing, Supervision; TPS – Experimentation, Resources; LRK, MSK – Resources, Validation and Supervision, Funding.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Authors declare no potential conflict of interest existing between them.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sivalingam, S., Sathishkumar, T.P., Rajeshkumar, L. et al. Failure analysis of hybrid fiber reinforced polymer composite tubes subjected to quasi-static compressive load: an experimental study. Sci Rep 15, 26966 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12242-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12242-w