Abstract

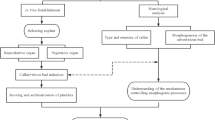

Tea, one of the world’s three major non-alcoholic beverages, sustains enormous annual consumption globally. However, the growth and development time of tea trees is long, the planting is affected by time and region, and it is not conducive to the diversification and innovation of tea varieties. To establish an efficient in vitro regeneration system for tea plant, the effects of culture conditions and plant growth regulators (PGRs) on adventitious bud differentiation and rooting were investigated in this study. The large-leaf tea variety ‘Yunkang 10’ was used for explant collection and the MS (Murashige and Skoog) medium was adopted as the basal medium. Callus induction peaked at 100% on the MS medium supplemented with 3.0 mg/L 6-benzylaminopurine (BAP) and 0.2 mg/L naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA). Optimal subculture occurred on MS + 3.0 mg/L BAP + 0.3 mg/L NAA + 3.0 mg/L gibberellic acid (GA3), while maximal proliferation (> 300% increase) used MS + 0.2 mg/L BAP + 0.1 mg/L NAA + 3.0 mg/L GA3. Nine-month-old calli showed highest bud differentiation (24.73% per callus) on MS + 2.0 mg/L BAP + 0.2 mg/L NAA and adventitious bud proliferation reached 89.64% on MS + 1.5 mg/L BAP + 0.1 mg/L NAA. Paraffin sectioning of calli at different stages confirmed adventitious bud origin. For the rooting induction rate, it peaked at 78.56% on 1/8 MS + 3.0 mg/L indole-3-butyric acid (IBA). Then the tissue cultured seedlings were moved into the field, and the transplantation using soil: humus: perlite = 6:3:1 achieved 71.11% survival. Further Start Codon Targeted (SCoT) marker analysis confirmed the genetic fidelity in the regenerated tea plants. The optimized system developed here enhances tea propagation and supports future genetic engineering efforts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tea, one of the most famous flavored and therapeutic non-alcoholic beverages, is consumed by two-thirds of the people all over the world due to its unique taste and health benefits1,2,3. Both the fresh leaves and processed products of tea plants are rich in polyphenols, polysaccharides and theanine, which provide various health effects, including anti-bacterial, anti-viral, anti-inflammatory, anti-aging, anti-cancer and anti-allergy4,5,6,7. The tea plant (Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze) is an important cash crop. Currently, the global tea cultivation area is more than 5.31 million hectares, and the annual output of tea products is approximately 6.3 million tons with an economic value of more than 17 billion US dollars8. With the development of tea industry, the cultivation and preservation of high-quality germplasm resources is particularly important. However, accumulation of viruses occurs in tea plants during the process of asexual propagation (grafting or cutting), resulting in low plant vitality and consequent reduced quality of processing products9. In vitro plant tissue culture techniques have the advantages of high genetic stability and adaptability, thus facilitate genetic improvement and breeding. Therefore, it is necessary to develop in vitro culture techniques for the proliferation of critical genetic resources of tea plants .

The ‘Yunkang 10’ variety (C. sinensis var. assamica cv. Yunkang 10), originated from Yunnan Province, China, belongs to the large-leaf tea species10. It was bred and certified as a state-level variety in 1987. Due to the characteristics of high yield, excellent quality, strong resistance to stress and wide adaptability, it is an ideal raw material for processing into Pu’er tea, green tea and black tea, the plant tissue culture of tea plant has made some progress in callus culture and preservation of germplasm resources. However, its application is still limited for the scarce of stable or efficient of the regeneration system11. Although researchers have produced some complete plants from mature embryos of tea plants using a callus induction protocol, the adventitious bud differentiation rate was only 14.2%12. Predecessors induced somatic embryos in tea (Camellia sinensis L. assamica × sinensis), but these embryos did not differentiate into buds13. Most previous studies used cotyledon explants, mature seeds, and stem segments of tea plants with axillary buds as explants, which were easier to differentiate buds. Still, there are few reports on the regeneration of the stem segment without axillary buds14,15,16. The plant tissue culture of tea plant has many problems such as an extended period, limited materials, and a low callus induction rate17. The tea plant is cross-pollinating, so it is difficult to obtain pure lines by self-crossing, which brings considerable obstacles to its genetic breeding11,18.

The lack of an efficient regeneration system has dramatically hindered the research on the genetic transformation of tea plants. The in vitro plant culture technology can not only be used to produce a large number of excellent clonal plants but also to overcome barriers, such as the influence of season and environment, which is of great significance for the conservation and improvement of germplasm resources19. Here, we established an efficient in vitro regeneration system of the large-leaf tea plant from stems without axillary buds to lay a foundation for the study of the genetic transformation of tea plants.

As one of the main methods to identify crop varieties, DNA molecular marker technology is widely used in tea plant’s genetic relationship identification20. The Start Codon Targeted (SCoT) marker is a novel molecular marker developed by Collard21. Based on the principle of initiation codon (ATG) in plant genes flanking conserved sequences, single primers were designed to amplify target genes. The SCoT markers have the advantages of easy development, low cost, high repeatability, and examining plant’s total genome randomly22,23. Therefore, the SCoT molecular markers were selected for the genetic fidelity detection of tea plants in this study.

This study aims to investigate the effects of different PGRs combinations on callus induction, adventitious bud differentiation, and plant regeneration of the ‘Yunkang 10’ tea plant. In this paper, an efficient regeneration system of ‘Yunkang 10’ tea plants was established, it laid a foundation for further improving tea quality and genetic engineering.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and culture condition

The tissue materials of ‘Yunkang 10’ tea plants were obtained from the laboratory of Southwest Forestry University, Yunnan Province, China, and were used in this study. MS (Murashige and Skoog, 1962) medium comprising 3% (w/v) sucrose as the carbon source and 0.8% (w/v) agar as the solidifying agent were used as the basal medium in this study, and the pH of the medium was adjusted to 5.8 before autoclaving at 121 °C for 20 min. The medium was supplemented with varying concentrations of the PGRs, including BAP (6-benzylaminopurine), IBA (indole-3-butyric acid), NAA (naphthaleneacetic acid), and GA3 (gibberellic acid 3). All the plant growth regulators were originated from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). The artificial climate condition was programmed with 70% relative humidity, the illumination intensity of 2 000 Lux, 16/8-h light/dark cycle, and 25 ± 2 °C.

Callus induction and proliferation

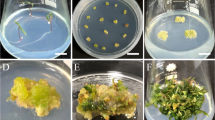

The stem segments of the eight-month-old healthy tissue culture tea plants (Fig. 1a) were used as explants. The stem segments (excluding axillary buds) were cut into a size of about 0.5 cm by a sterile scalpel on the clean bench and then inoculated on the MS medium. To determine the optimal concentration of PGRs for callus induction, a base of MS medium with different concentrations of PGRs, including BAP (0, 1.5, 2.0, 3.0 mg/L) and NAA (0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3 mg/L). Callus induction was conducted under dark conditions at 25 ± 2 °C, and the statistical data collection was performed after 30 d of culture. Callus percentage induction (%) = (the number of callus explants/the number of inoculated explants) × 100%. The status of the callus was observed and recorded periodically.

In vitro regeneration process of the tea plant: (a) Eight-month-old tissue culture plants. (b) Dumbbell-shaped, loose and dark green callus. (c) Compact and white callus. (d) Loose granular, light green callus. (e) Compact, dark green callus. (f) Callus with adventitious buds. (g) Plant was further differentiated into plantlet. (h) Plants was transplanted into field.

In the process of callus subculture, the aged calli were removed, and the well growing calli were cut into a size of about 0.5 cm in diameter, and then transferred to the same fresh medium. The calli were subcultured every 30 d, and the proliferation coefficient was calculated after 30 d of culture. Callus proliferation coefficient = the volume of callus at 30 d/the volume of callus at inoculation. For callus proliferation, MS medium with different concentrations of PGRs including BAP (1.0, 2.0, 3.0 mg/L), NAA (0.1, 0.2, 0.3 mg/L) and GA3 (0, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0 mg/L).

Adventitious bud induction and proliferation

To induce adventitious buds, the calli of different ages were inoculated on MS medium with varying concentrations of BAP (0, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0 mg/L) and NAA (0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3 mg/L). The calli of different ages included 3, 6, and 9 months (after 3, 6, or 9 times of callus subculture) were inoculated on the adventitious bud induction medium. The adventitious bud differentiation rate was calculated after 30 d of culture. Adventitious bud differentiation rate (%) = (the number of calli with adventitious buds/the number of inoculated calli) × 100%.

When the buds grew to 2–3 cm, the buds were clipped into MS medium containing BAP (1.0, 1.5, 2.0 mg/L) and NAA (0.05, 0.1 mg/L) for bud proliferation. The proliferation coefficient of buds was calculated after 30 d of culture. Proliferation coefficient = the number of effective buds/the number of inoculated buds.

Histological analysis

To clearly understand the dynamics of morphogenesis, sample sections were taken at four periods, including callus stage in loose state, compact, budding differentiation, and the leaf formation stage. The calli were cut into 20 mm × 20 mm squares and fixed in fixative solution (formaldehyde 5 mL, glacia lacetic acid 5 mL, 70% alcohol 90 mL) for 24 h, dehydrated with hierarchical alcohol for 60 min, removed with xylene, embedded in paraffin, and then sliced with a rotary slicer (Zhongyi Youxin Technology Co. Ltd., Beijing, China). The slices were stained with hematoxylin for 10 min, blued with warm water for 2 min, washed with 70% alcohol for 2 min, and stained with eosin for 1 min. Then, they were sequentially washed with 80%, 95%, and 100% ethanol solution and dried naturally. Finally, a drop of neutral gum was placed near the tissue, and the cover glass was gently covered with air drying and preserved. The images were captured under the light microscope (Eclipse50i, Nikon).

Root induction

When the adventitious shoots grew to 3–4 cm, they were inoculated on the rooting medium. The root induction was carried out with MS, 1/2 MS, 1/4 MS, 1/8 MS, 1/16 MS, and IBA (1.0, 2.0, 3.0 mg/L). After 30 days of culture, the root length was measured, and the rooting rate was calculated. Rooting rate (%) = (number of rooted seedling / number of grafted seedlings) × 100%.

Transplanting of tissue culture plants

The rooted tissue culture seedlings were moved into the greenhouse for about 20 days. The lighting intensity of the greenhouse was 4000 Lux, and the shading degree was 50%-70%. After opening the bottles, tissue culture plants were kept stationary for 3 days at 70% relative humidity, 2000 Lux illumination intensity, 16/8 h light/dark cycle, and 25 ± 2 °C. Soil, humus, and perlite were mixed in proportions (4.5:4.5:1; 6:3:1; 3:6:1) as a composite substrate and poured into seedling pots. The tissue-cultured tea seedlings were taken out from the culture bottle and put into the substrate. Finally, it was moved to the greenhouse. Transplantation survival rate (%) = (number of healthy growth lines/number of transplantation lines) × 100%.

DNA isolation and genetic fidelity analysis by SCoT

The whole plant genomic DNA was extracted from 500 mg leaf samples of three randomly selected regenerated lines and the mother plant of ‘Yunkang 10’ by using the Super Plant Genomic DNA Kit (Tiangen Biotech Co. Ltd., Beijing, China). They were tested by three randomly selected SCoT primers from the reports of Srivastava et al. (2020). The total volume of 20 µL PCR reaction was carried out containing 1 µL plant DNA (25–30 ng), 2 µL primer, 10 µL Green Taq PCR Mix (Nanjing Vazyme Biotech Co. Ltd., Nanjing, China), and 7 µL ddH2O. The PCR amplifications were performed on a thermal cycler (Eppendorf, Germany) programmed for initial denaturation at 94 °C for 3 min, 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 50 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 2 min; final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. The amplified PCR products were separated by agarose gel (2%) using TAE (1 ×) buffer with 70 V for 1 h, and documented using a gel documentation system (Bio-Rad, USA). The sizes of the amplified PCR products were determined against a 100 bp—2 kb DNA Marker (TaKaRa, Japan).

Statistical analysis

SPSS 25.0 was used for data analysis and chart production. Tissue culture plant proliferation, callus induction, callus proliferation, bud differentiation, bud proliferation, rooting and seedling transplantation and seedling hardening were repeated three times, with at least 30 explants. Statistical significance was tested by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with P < 0.05 and determined by Duncan’s multiple interval test.

Results

Callus induction and proliferation

Callus appeared after 15 days of culture, and the callus induction rate was 87.22%—100.00%. All combinations of BAP and NAA successfully induced callus, but no callus was produced when no PGRs were added to the culture medium (Table 1). The callus induction rate was the lowest at 87.22%, and MS + 2.0 mg/L BAP + 0.1 mg/L NAA produced dense white callus. The results showed that when the BAP concentration was 2.0 mg/L, changes in NAA concentration had no significant effect on the induction rate of callus. Still, the characteristics of the callus were different, including dense, white and loose, light green. MS + 1.5 mg/L BAP + 0.2 mg/L NAA induced loose granular and light green callus with an induction rate of 100%. MS + 3.0 mg/L BAP + 0.2 mg/L NAA produced the highest callus induction rate (100%), inducing dumbbell-shaped, loose and dark green callus (Fig. 1b). According to the callus induction rate and callus status, MS + 3.0 mg/L BAP + 0.2 mg/L NAA is the best medium for callus induction in tea plant stem segments.

The proliferation coefficient and the growth status of callus were improved with the increase of BAP concentration. GA3 concentration exerted a synergistic effect in promoting callus growth (Table 2). MS + 3.0 mg/L BAP + 0.3 mg/L NAA + 3.0 mg/L GA3 showed the best growth status characterized by the loose granular, light green callus, and it showed the highest proliferation coefficient (2.60) of callus, which was considered to be the optimal medium for the callus subculture. On the whole, with the subculture, the callus was compact and white after subcultures of 3 times (Fig. 1c), loose and light green after subcultures of 6 times (Fig. 1d), and became compact and dark green after subcultures of 9 times (Fig. 1e).

Proliferation of adventitious shoots

The medium with the addition of GA3 promoted the growth speed of tissue culture plants, while the proliferation coefficient decreased (Table 3). MS + 0.2 mg/L BAP + 0.1 mg/L NAA + 3.0 mg/L GA3 showed the fastest growth speed, but they only excessive growth, and their proliferation coefficient was poor. MS + 1.5 mg/L BAP + 0.2 mg/L NAA and MS + 2.0 mg/L BAP + 0.2 mg/L NAA showed the highest proliferation coefficient, reaching 4. 33 (Table 3). The height of the combination of MS + 1.5 mg/L BAP + 0.2 mg/L NAA in adventitious shoots was 4. 36 ± 0.34b which is better than MS + 2.0 mg/L BAP + 0.2 mg/L NAA. Considering comprehensively, MS + 1.5 mg/L BAP + 0.2 mg/L NAA was regarded the best medium for the proliferation of adventitious shoots.

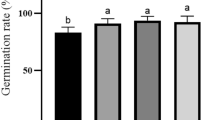

Bud differentiation and proliferation

The callus at the age of 3 or 6 months could not differentiate into buds; however, after 9 times of callus subculture, the adventitious buds appeared (Fig. 1f). Generally, the green callus differentiated more quickly than the white ones. The bud differentiation rate in cultures inoculated on MS + 1.0 mg/L BAP + 0.1 mg/L NAA was 0, the same as that of MS without PGRs. It was shown that when the concentration of BAP was too low (1.0 mg/L) or too high (3.0 mg/L), the adventitious bud differentiation rate was not ideal. We found that the best concentration of BAP was 2.0 mg/L, which significantly increased the bud differentiation rate compared with the other two concentrations. The ratio of BAP and NAA was crucial for the bud differentiation. In this study, when the ratio of BAP to NAA was high (2.0/0.1) or low (2.0/0.3), the bud differentiation rate was low. The highest bud differentiation rate was observed when the ratio of BAP to NAA was tenfold (2.0/0.2), which was significantly higher (P < 0.05) than that of other media (Fig. 2). Therefore, MS + 2.0 mg/L BAP + 0.2 mg/L NAA was the best medium for the bud differentiation.

BAP and NAA synergistically induce the proliferation of adventitious buds. MS + 1.5 mg/L + 0.1 mg/L NAA has the highest proliferation coefficient (3.20) (Table 4) and the best growth condition. Under MS + 1.5 mg/L BAP + 0.05 mg/L NAA treatment, shoots with a secondary proliferation coefficient (2.00) grew well. When the BAP concentration is 1.0 or 2.0 mg/L, the proliferation coefficient is low, and the growth status is poor. Therefore, MS + 1.5 mg/L BAP + 0.1 mg/L NAA is an ideal shoot proliferation medium.

Histological analysis

In the early stages of organogenesis, the meristem centers were visible (Fig. 3). These tissue centers showed intense mitotic activity, leading to cell differentiation of the callus. The embryogenic callus was characterized by small cells, regular shape, large nucleus, dense arrangement, and high density of starch (Fig. 3a). In the region of callus formation, the epidermal cell layer of explants was differentiated into buds, and the differentiated buds contained protruding bud primordia (Fig. 3a-d). The more mature cells in the stem meristem formed the apical meristems and leaf primordiums (Fig. 3b-c). The stem tissues were splendidly differentiated and the leaf vasculars were formed (Fig. 3d). The paraffin section analysis showed that the adventitious buds could be successfully induced from the stem segments without axillary buds of tea plant.

Root induction

MS medium with a low concentration was more suitable for rooting tea plant tissue culture. MS + 1.0 mg/L IBA and 1/2 MS + 1.0 mg/L IBA did not generate roots, when the concentration of MS was reduced to 1/4, 1/8, or 1/16 without the addition of PGRs (Table 5), the test-tube plantlet were rooted (Fig. 1g). The highest rooting rate of 80% was achieved when tea plants were cultured on 1/8 MS + 3.0 mg/L IBA (Fig. 4a). With the increase of the IBA concentration, there was no significant difference in the rooting percentage and the root length (Fig. 4a,b), indicating that the concentration of IBA had no significant effect on the rooting of test-tube plantlet.

Transplantation of tissue culture plants

The survival rate of transplanted tissue culture plants is affected by the proportion of substrate. When the ratio of original soil, humus soil, and perlite was 6:3:1, the survival rate was the highest, reaching 71.11% (Table 6). When the content of raw soil was more significant than humus, and the transplant survival rate was high, and the status of seedlings was better than other combinations (Fig. 1h); when it was equal to or less than humus, the transplant survival rate was low.

The different letters indicate significant differences at P < 0.05 in Duncan’s test, each data represent mean ± standard error.

Genetic fidelity analysis

A total of 15 clear bands were amplified by three SCoT primers. Primers SCoT 1, SCoT 2 and SCoT 3 amplified 5, 6 and 4 clear bands, respectively, with the approximate range from 450 to 2500 bp size (Fig. 5) (Table 7). Compared with the mother plant, the in vitro regenerated lines had no notable bands, indicating that the regenerated tea plants were the same as the mother plant. The results showed no genetic variation in the regeneration of tea plants, which confirmed that the regeneration study was successful.

Discussion

In this study, the stem segments of the ‘Yunkang 10’ tea cultivar, devoid of axillary buds, were selected as explants for the purpose of identifying the most conducive conditions for callus induction, cellular differentiation, and the subsequent development of roots. Following the processes of rooting, the refinement of seedlings, and transplantation, fully regenerated plants were successfully cultivated. Consequently, a preliminary regenerative framework for the ‘Yunkang 10’ tea plants has been established.

Effects of different hormones on callus and adventitious buds of the tea plant

Different hormones have a significant effect on the induction of callus and adventitious buds in tea plants. The study shows that stem segments are more suitable than leaves for tissue culture because of their higher callus induction rate and better growth status24.The use of different types, concentrations and proportions of PGRs had a significant impact on the formation of tissue, development and organ differentiation of tea plants15. Someone reported that the synergistic effect of betaine and ABA on tea plant seed explants further improved the induction response25. MS medium containing 3.0 mg/L BAP + 0.1 mg/L NAA was the best medium for somatic embryogenesis26. When added at appropriate concentrations, BA could regulate cell cycle and cell division, stimulate adventitious bud proliferation13. It was observed that the callus induction rate was significantly higher (P < 0.05) when cytokinin and auxin were used together than when they were used alone27. In this study, we have set up multiple PGR combinations. Different concentrations of BAP and NAA induce different rates of callus induction. Some researchers used ‘ZiKui’ tea with hypocotyl as explants medium as WPM + 2.00 mg/L 6-BA + 0.10 mg/L IBA for callus induction, the efficiency was 91.85%28. However, we used stem segments of ‘Yunkang 10’ without axillary buds as explants and a combination medium of 3.0 mg/L BAP + 0.2 mg/L NAA for callus induction, with the highest callus induction rate of 100%. This fully demonstrates that our callus system is highly efficient.

In this study, GA3 was added in callus proliferation medium, which was beneficial to callus proliferation. It has been shown that GA3 enhances shoot elongation through internodal extension29. Gibberellin (GA3) is a plant hormone that requires a small amount of gibberellin to promote the growth and development of plants. Therefore, at the appropriate time, appropriate concentration, and appropriate exogenous application of growth regulators, favorable conditions can be induced in specific crops30,31. During cereal germination, GA causes the accumulation of mRNAs encoding hydrolytic enzymes involved in the mobilization of stored macromolecules which provide nutrients for the growing seedling32,33. The results showed that the multiplication coefficient of the medium added with GA3 increased significantly. The highest proliferation coefficient was 2.60, which was significantly higher (P < 0.05) than without GA3, and the callus status was outstanding.

Obtaining many adventitious buds was the critical step to achieving rapid tissue proliferation. Studies have shown that different plants exhibit varying hormone responses, necessitating optimization based on specific species. It was reported that the combination of 1 mg/L BAP + 0.05 mg/L NAA had the highest regeneration rate (100%) in the Dragon’s Head plant34. It was found in the experiment of Prunus persica, MS + 1.5 mg/L 6-BA + 0.1 mg/L IBA was the best combination for inducing adventitious buds with an induction rate of 82.9%35. In this study, the concentration and proportion of BAP and NAA were vital for the induction and proliferation of the adventitious buds. A high ratio of cytokinin to auxin was known to promote the bud differentiation36, the highest bud differentiation rate was obtained in this study when the ratio of BAP to NAA concentration was tenfold, the bud differentiation rate was the highest, which was 24.73%. Compared with ‘ZiKui’ tea with hypocotyl as explants as the explants culture medium MS + 2.0 mg/L 6-BA + 0.1 mg/L NAA and the bud differentiation rate was 19.03%28. Our system greatly improves the bud differentiation rate.

Concentration of basal MS medium affects healing tissue induction for rooting

In this study, the main factor affecting the rooting of in vitro seedlings was the concentration of MS medium; semi-strength MS medium has been shown to be more favorable for root formation in many plants than full strength MS medium37. Low concentration of nutrients in the culture medium is beneficial to rooting, which may be because too much nutrients also cause high osmotic pressure, which is unfavorable to the physiological state of cells and limits cell division38. Several studies have shown that the use of growth factors (IBA or NAA) can promote normal rooting in some plants39,40. Application of IBA induces adventitious roots, due to an increase in the biosynthesis of IAA41. Furthermore, auxin receptors in the formation of rhizomes have different affinities, and plant growth regulators have varying root-inducing abilities42. It was clearly pointed out that semi-strength MS medium can significantly promote the rooting of acacia trees43, which may be because high concentration of inorganic salts inhibit callus formation. Furthermore, 1/2 MS combined with IBA hormone has the best rooting effect44. The rooting rate could increase to about 95.22% when 1/2 MS + 0.2 mg/L IBA medium for Tussilago farfara45. It has also been shown that some plants can be successfully rooted on media that do not contain auxins46,47. In this study, no roots were formed when the MS medium concentration was higher than 1/4, the best formula was 1/8 MS + 3.0 mg/L IBA.

Physiological age affects callus differentiation and bud formation

The results showed that the number of successional cultures and physiological age of histocultured plants affected the differentiation of callus tissues and bud formation. It was found that when the number of generations of callus was less, the proliferation ratio of callus increased with the number of generations48, and the browning rate gradually decreased. Among them, the callus with 4 generations had the best growth condition in culture, and the embryogenic callus of ryegrass (Lolium perenne) has a high regenerative capacity in vitro culture studies, it tends to lose its embryogenic nature during subsequent cultures49. Long-term subculturing (typically exceeding 13 passages) significantly impacts the morphogenesis capacity and genetic stability of callus tissue. For instance, after over one year of subculture, most materials exhibit substantial alterations in both morphogenesis capability and genetic stability50. In the experiment of golden thread vine (Tetrastigma hemsleyanum), the regeneration rate began to decrease after 4 generations, and the differentiation ability was completely lost in the 15th generation51. The long-term culture of bird axle grass (Lotus corniculatus) also confirmed that although the callus tissue kept for 1.5–2.5 years had the ability to regenerate, the bud regeneration rate decreased sharply after this time limit52. However, there are exceptions; for instance, It was observed that the leaf clusters of Paeonia ostii ‘Feng Dan’ began to develop and elongate after 11 to 12 subcultures53. After one year of cultivation on callus proliferation medium, the differentiation potential of herbaceous bamboo (Mniochloa abersend) increased54. The research on the embryogenic callus of Vanilla showed that after 24 consecutive generations over two years, the somatic embryos still maintained a high regeneration rate (over 80%)55. In the present study, the age of 3- 6-months callus had no ability to differentiate into buds, but after nine callus subcultures, adventitious buds appeared. This may be due to the accumulation of physiological age and changes in starch content and hormone levels in callus tissues, which increased the activity of callus tissues after multiple subcultures56,57. The different conclusions may also be attributed to differences in the use of various organs as explants to establish plant regeneration systems, as well as differences in plant types.

Discussion of the start codon targeted and histology

In this study, the somatic embryos were generated indirectly through callus. Indirect somatic cell embryogenesis is the main way to indirectly generate somatic cells from callus tissue. This process not only has an advantage in quantity, but also shows high efficiency in regeneration rate and plant quality58. The observations are in agreement with the findings of previous studies where embryogenic calli exposed meristematic cells with high division rates and isodiametric cells with small, and dense cytoplasm59. The compact, small, and isodiametric cells with dense cytoplasm indicate that the calli were embryogenic and high density of starch was an important condition for plant organogenesis60. Histological analysis provides information for the ultrastructure of calli for the purpose of selecting embryogenic calli for further regeneration processes61. In the process of tea plants callus formation, the parenchyma cells around the medium, small veins and the main veins of the mesophyll were initiated first, which were divided after dedifferentiation, then formed meristematic cell clusters, finally formed callus. Next, somatic embryos were generated from callus, and the number of somatic embryos was large, which continued to differentiate and proliferate.

Somaclonal variation refers to the genetic material variation or epigenetic variation in the cultured cells or plants during long-term continuous culture, which is not conducive to maintaining the genetic consistency of clonal offspring62,63. It is crucial to check the variation of regenerated plants. SCoT markers also have broad application prospects in crop improvement, genetic resources conservation and utilization64. Studies showed that SCoT markers could be used for genetic basic research on tea plants65. This study employed SCoT labeling technology, where the initiation codon (ATG) serves as the starting point for gene translation. The flanking sequences of this codon are highly conserved and consistency66. No deletions or insertions were observed in PCR amplification bands, indicating no DNA-level mutations occurred during the in vitro regeneration of tea plants. The regeneration system proposed in this study can be used for tea production and subsequent development.

Conclusion

This study utilized the large-leaf tea plant ‘Yunkang 10’ as a model organism, selecting its axillary bud-free stem segments as explants. Through experiments at different stages of regeneration, we systematically screened optimal conditions for inducing callus formation, bud differentiation, and rooting. The final optimized results were: MS medium with 3.0 mg/L BAP and 0.2 mg/L NAA, MS medium with 1.5 mg/L BAP and 0.2 mg/L NAA for optimal bud differentiation, and 1/8 MS medium with 3.0 mg/LIBA for optimal rooting. Subsequent seedling cultivation and transplantation successfully produced complete regenerated plants. SCoT molecular marker analysis confirmed no DNA-level mutations in the regenerated tea plants. As Yunnan Province’s tea industry predominantly relies on high-value large-leaf varieties with widespread market appeal, our efficient in vitro regeneration system using ‘Yunkang 10’ will provide technical support for developing rapid propagation systems, genetic transformation, and variety improvement in industrialized tea production.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Chen, J. D. et al. The chromosome-scale genome reveals the evolution and diversification after the recent tetraploidization event in tea plant. Hortic. Res. 7(1), 63 (2020).

Jiang, C. K. et al. Non-volatile metabolic profiling and regulatory network analysis in fresh shoots of tea plant and its wild relatives. Front. Plant Sci. 12, 746972 (2021).

Ma, L. L. et al. Analysis of the biochemical and volatile components of Qianlincha and Qiandingcha prepared from Eurya alata Kobuski and Camellia cuspidate. Agronomy 11(4), 657 (2021).

Hazarika, R. R. & Chaturvedi, R. Establishment of dedifferentiated callus of haploid origin from unfertilized ovaries of tea (Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze) as a potential source of total phenolics and antioxidant activity. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Plant. 49, 60–69 (2013).

Soni, R. P., Katoch, M., Kumar, A., Ladohiya, R. & Verma, P. Tea: Production, composition, consumption and its potential as an antioxidant and antimicrobial agent. Int. J. food. Ferment. Technol. 5, 95–106 (2015).

Chen, Y. Y. et al. Characterization of functional proteases from flowers of tea (Camellia sinensis) plants. J. Funct. Foods. 25, 149–159 (2016).

Huang, F. F. et al.. Relationship between theanine, catechins and related genes reveals accumulation mechanism during spring and summer in tea plant (Camellia sinensis L). Sci. Hortic. 2022, 302 (2022).

Chen, S. et al. Gene mining and genomics-assisted breeding empowered by the pangenome of tea plant Camellia sinensis. Nat. Plants 9(12), 1986–1999 (2023).

Tian, A. L. et al. Research progresses on culture types in vitro and applications of tea plant. J. Henan Agric. Sci. 46(5), 1–7 (2017).

Li, M. W., Shen, Y., Ling, T. J., Ho, C. T. & Xie, Z. W. Analysis of differentiated chemical Components between Zijuan Purple Tea and Yunkang Green Tea by UHPLC–Orbitrap–MS/MS Combined with Chemometrics. Foods (Basel, Switzerland) 10(5), 1070 (2021).

Mondal, T. K., Amita, B., Malathi, L. & Paramvir, S. A. Recent advances of tea (Camellia sinensis) biotechnology. Plant Cell Tiss Org Cult. 76, 195–254 (2004).

Cai, H. Y., Jiang, C. J., Wang, Z. X. & Wan, X. C. Study on the induced plantlet from mature embryo of tea plant. J. Biol. 24, 21–23 (2007).

Ghanati, F. & Ishkaa, M. R. Investigation of the interaction between abscisic acid (ABA) and excess benzyladenine (BA) on the formation of shoot in tissue culture of tea (Camellia sinensis L). Int. J. Plant. Prod. 3, 7–14 (2009).

Bano, Z., Rajaratnam, S. & Mohanty, B. D. Somatic embryogenesis in cotyledon culture of tea (Thea sinensis L). J. Hort. Sci. 66, 465–470 (1991).

Sun, J. et al. Shoot basal ends as novel explants for in vitro plantlet regeneration in an elite clone of tea. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotech. 87, 71–76 (2012).

Tian, A. L. et al. Tissue culture and rapid propagation of Camellia sinensis Dahongpao. Plant Physiol. 53, 619–624 (2017).

Akula, A. & Dodd, W. A. Direct somatic embryogenesis in a selected tea clone, ‘TRI-2025’ (Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze) from nodal explants. Plant Cell Rep. 17, 804–809 (1998).

Bhattacharya, A., Nagar, P. K. & Ahuja, P. S. Seed development in Camellia sinensis (L) O. Kuntze. Seed Sci. Res. 12, 39–46 (2002).

Singh, R., Rai, M. K. & Kumari, N. Somatic embryogenesis and plant regeneration in Sapindus mukorossi Gaertn from leaf-derived callus induced with 6-benzylaminopurine. Appl. Biochem. Biotech. 177, 498–510 (2015).

Lin, W. D., Chen, Z. D., Sun, W. J. & Yang, R. X. Analysis of genetic diversity of Fujian tea varieties by SCoT markers. J. Tea Sci. 38, 43–57 (2018).

Collard, B. Y. & Mackill, D. Start Codon Targeted (SCoT) polymorphism: A simple, novel DNA marker technique for generating gene-targeted markers in plants. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 27, 86–93 (2009).

Chirumamilla, P., Gopu, C., Jogam, P. & Taduri, S. Highly efficient rapid micropropagation and assessment of genetic fidelity of regenerants by ISSR and SCoT markers of Solanum khasianum Clarke. Plant Cell Tissue Org. Cult. 144, 397–407 (2021).

Buer, H., Rula, S., Wang, Z. Y., Fang, S. & Bai, Y. E. Analysis of genetic diversity in Prunus sibirica L. in inner Mongolia using SCoT molecular markers. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 69, 1057–1068 (2022).

Wang, Y. Effects of different hormone ratios on tissue culture of tea seedlings. J. Anhui Agri. Sci. 34(14), 3312–3313 (2006).

Akula, A., Akula, C. & Bateson, M. Betaine a novel candidate for rapid induction of somatic embryogenesis in tea (Camellia sinensis (L) O Kuntze). Plant Growth Regul. 30, 241–246 (2000).

Seran, T. H., Hirimburegama, K. & Gunasekare, M. T. K. Somatic embryogenesis from embryogenic leaf callus of tea. (Camellia sinensis L) Tropical Agric. Res. 18 (2006).

Okello, D. et al. Indirect in vitro regeneration of the medicinal plant, Aspilia africana, and histological assessment at different developmental stages. Front. Plant Sci. 12, 797721 (2021).

Jin, J. et al. Establishment of an efficient regeneration system of ‘ZiKui’ tea with hypocotyl as explants. Sci. Rep. 14, 11603 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. Efficient culture protocol for plant regeneration from petiole explants of physiologically mature trees of Jatropha curcas L. Biotechnol. Biotech. Eq. 29(3), 479–488 (2015).

Deotale, R. D., Mask, V. G., Sorte, N. V., Chimurkar, B. S. & Yerne, A. Z. Effect of GA3 and IAA onmorpho-physiological parameters of soybean. J. Soils Crops. 8(1), 91–94 (1998).

Abd, E. I. Effect of phosphorus, boron, GA3 and their interactions on growth, flowering, pod setting, abscission and both green pod and seed yields of broad been (Vicia faba L.) plant. Alexandr. J. Agrc. Res. 42(3), 311–332 (1997).

Brown, P. H. & Ho, D.T.-H. Barley aleurone layers secrete a nuclease in response to gibberellic acid. Plant Physiol. 82, 801–806 (1986).

Hammerton, R. W. & Ho, D.T.-H. Hormonal regulation of the development of protease and carboxypeptidase activities in barley aleurone layers. Plant Physiol. 80, 692–697 (1986).

Ebrahimzadegan, R. & Maroufi, A. In vitro regeneration and Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation of Dragon’s Head plant (Lallemantia iberica). Sci. Rep. 12, 1–12 (2022).

Han, S. S., Zhang, L. Y. & He, Q. Study on tissue culture and protoplast preparation of nectarine(Prunus persica var Nectarine). J. Southwest Univ. Nat. Sci. 37(05), 23–30 (2015).

Jia, Y. et al. Callus induction and haploid plant regeneration from baby primrose (Primula forbesii Franch) anther culture. Sci. Hortic. 176, 273–281 (2014).

Soni, M. & Kaur, R. Rapid in vitro propagation, conservation and analysis of genetic stability of Viola pilosa. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants. 20, 95–101 (2014).

Asadak. Chloroplast: Formation of activeoxygenan ditsscavenging. Methods Enzymol. 105, 422–429 (1984).

Annika, E. K., Nathan, D. & Roberto, G. L. A foliar spray application of indole-3-butyric acid promotes rooting of herbaceous annual cuttings similarly or better than a basal dip. Sci. Hortic. 304, 111298 (2022).

Lorenzo, F. et al. Indole-3-butyric acid promotes adventitious rooting in Arabidopsis thaliana thin cell layers by conversion into indole-3-acetic acid and stimulation of anthranilate synthase activity. BMC Plant Biol. 17, 121 (2017).

Woodward, A. W. & Bartel, B. Auxin: Regulation, action, and interaction. Ann Bot. 95, 707–735 (2005).

Tereso, S. et al. Improved in vitro rooting of Prunusdulcis Mill. Cultivars. Biologiaplanarum. 52, 437–444 (2008).

Gonçalves, S., Correia, P. J., Martins-Loução, M. A. & Romano, A. A new medium formulation for in vitro rooting of carob tree based on leaf macronutrients concentrations. Biol. Plant. 49(2), 277–280 (2005).

Dewir, Y. H., El-Mahrouk, M. E., Murthy, H. N. & Paek, K. Y. Micropropagation of Cattleya: Improved in vitro rooting and acclimatization. Hortic. Environ. Biotechnol. 56(1), 89–93 (2015).

Ren, J. W., Lei, Y. & Li, X. L. Tissue culture of callus and establishment of regeneration system of Tussilago farfara petiole. China J. Chin. Mater. Med. 42, 3895–3900 (2017).

Derya, G., Muhammad, A. & Sebahattin, Ö. In vitro rooting without exogenous auxins and acclimatization of Fritillaria species of Turkey. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 22, S140 (2011).

Megumi, M. et al. Plant regeneration from cell suspension-derived protoplasts of Primula malacoides and Primula obconica. Plant Sci. 160(6), 1221–1228 (2001).

Jin, X. L., Wang, Z., Liu, X. M. & Du, H. Y. Optimization of Subculture Conditions of Eucommia ulmoides Callus. Journal of Henan Agricultural Sciences 43(5), 138–141 (2014).

Newell, C. A. & Gray, J. C. Regeneration from leaf-base explants of Lolium perenne L And Lolium multiflorum L. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 80(2), 233–237 (2005).

Liu, L. M., Tang, H. R. & Liu, J. Morphogenetic capacity and genetic stability of tissue in vitro cultures in long-term subculturing. Biotechnol. Bull. 05, 22–27 (2008).

Peng, X., Zhang, T. & Zhang, J. Effect of subculture times on genetic fidelity, endogenous hormone level and pharmaceutical potential of Tetrastigma hemsleyanum callus. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Culture 122(1), 67–77 (2015).

Orshinsky, B. R. & Tomes, D. T. Effect of Long-term Culture and Low Temperature Incubation on Plant Regeneration from a Callus Line of Birdsfoot Trefoil (Lotus corniculatus L). J. Plant Physiol. 119(5), 389–397 (1985).

Xu, L., Cheng, F. Y. & Zhong, Y. Efficient plant regeneration via meristematic nodule culture in Paeonia ostii ‘Feng Dan’. Plant Cell, Tissue Organ Cult. 149(3), 599–608 (2022).

Zang, Q. L. et al. Callus induction and plant regeneration from lateral shoots of herbaceous bamboo Mniochloa abersend. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 92(2), 168–174 (2016).

Yang, B. B., Xia, H. P. & Ma, Z. R. Study on tissue culture of Vanilla. Acta Prataculturae Sinic 16(4), 93–99 (2007).

Ahmad, A. et al. The effects of genotypes and media composition on callogenesis, regeneration and cell suspension culture of chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla L.). PeerJ. 9, e11464 (2021).

Diaz-Sala, X. Molecular dissection of the regenerative capacity of forest tree species: Special focus on conifers. Front. Plant Sci. 9, 193 (2019).

Wei, D. X., Zhang, T., Zheng, Y. Y. & Yu, X. N. Histocytology observation on the somatic embryogenesis in herbaceous peony callus. Bull. Bot. Res. 38(01), 56–63 (2018).

Vega, R., Vásquez, N., Espinoza, A. M., Gatica, A. M. & Valdez-Melara, M. Histology of somatic embryogenesis in rice (Oryza sativa cv. 5272). Rev. Biol. Trop. 57, 141–150 (2009).

Kim, Y. G. et al. Histological assessment of regenerating plants at callus, shoot organogenesis and plantlet stages during the in vitro micropropagation of Asparagus cochinchinensis. Plant Cell Tissue Org. Cult. 144, 421–433 (2021).

Oliveira, E. J. et al. Morpho-histological, histochemical, and molecular evidences related to cellular reprogramming during somatic embryogenesis of the model grass Brachypodium distachyon. Protoplasma 254, 2017–2034 (2017).

Neelakandan, A. K. & Wang, K. Recent progress in the understanding of tissue culture-induced genome level changes in plants and potential applications. Plant Cell Rep. 31, 597–620 (2012).

Shan, X. H., Li, Y. D., Tan, M. & Zhao, Q. Tissue culture-induced alteration in cytosine methylation in new rice recombinant inbred lines. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 11(19), 4338–4344 (2012).

Rai, M. K. Start codon targeted (SCoT) polymorphism marker in plant genome analysis: Current status and prospects. Planta 257, 34 (2023).

Chen, X., Zhang, Y., Li, J., Xi, Y. J. & Zhang, Y. Q. Genetic diversity analysis of tea germplasm in Shaanxi Province based on SCoT marker. J. Tea Sci. 36(2), 131–138 (2016).

Sawant, S. V. et al. Conserved nucleotide sequences in highly expressed genes in plants. J. Genet. 78, 123–131 (1999).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by Technology talent and platform plan (202305AF150058), Science and technology innovation team (202204AC100001-TD01) and Scientific Research Fund project of Yunnan Education Department, China (2024Y587).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TW conceived the idea. XLZ, HMZ, and ML performed the experiments. ML, ML, and HMZ analyzed the data. ML and XLZ wrote the primary draft, which was further augmented, edited, and improved by LFY and TW. All the authors read and approved this article for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Xl., Lu, M., Li, M. et al. Efficient callus induction and regeneration of tea plant (Camellia sinensis). Sci Rep 15, 26848 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12271-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12271-5