Abstract

The potential risks of osteoarthritis (OA) progression in the lateral compartment during the progression of medial knee OA and after medial unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) remain to be elucidated. Thus, five medial knee OA models with different progression stages and one medial UKA model were established using the finite element method to investigate the biomechanical differences of lateral compartment articular cartilage (AC). The AC and meniscus were constructed by fibril-reinforced biphasic material, and the real biphasic contact conditions were adopted. The results showed that biomechanical differences in lateral compartments were within 2% between the healthy knee model (OARSI 0–1) and early medial knee OA models (OARSI 2–3). However, in advanced medial knee OA (OARSI 4.5), up to a 7.0% increase in stress and a 22.2% increase in a strain of the lateral compartment AC were predicted. After medial UKA surgery, the maximum shear strain of the lateral compartment AC was reduced by about 22.2% when compared with advanced medial knee OA. In conclusion, the progression of medial knee OA may cause OA development in the lateral compartment. In contrast, medial UKA surgery might help to lower the risks of OA progression in the lateral compartment when in the advanced medial knee OA stage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a common degenerative joint disease. During the progression of knee OA, articular cartilage (AC) and meniscus will degenerate, be partly worn out and finally lost1,2. The medial osteoarthritis is more likely to be induced, as it carries more loads than the lateral side3,4. At the end stage of medial knee OA, unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) is recognized as an effective treatment method4.

Medial knee OA and medial UKA not only change the biomechanical behaviours in the diseased compartment, but also influence the lateral compartment4,5, which might induce lateral knee OA eventually. Previous histologic analysis of AC6 has shown that patients with obvious medial knee OA might also have mild lateral knee OA. After medial UKA surgery, OA progression in the lateral compartment, one of the main postoperative indications, accounts for approximately 30% of UKA revisions7. However, the biomechanics of the lateral compartment AC during the progression of medial knee OA and after medial UKA remain to be quantified. According to previous studies8,9, investigating the biomechanical behaviours of AC could help to understand the potential risk of initial knee OA. For example, the excessive stresses and strains might be associated with the death of the chondrocyte, the degeneration of collagen and the damage of AC10,11. Therefore, studying the biomechanical behaviours of AC could help to understand the potential risk of OA progression in the lateral compartment during the progression of medial knee OA and after medial UKA.

AC is a soft tissue covering the end of diarthrodial joints and distributes stresses to the bones12. AC could be represented as a fibril-reinforced biphasic material that consists of a porous solid matrix saturated by a large proportion of interstitial fluid and reinforced by collagen fibres12. It is usually characterised by three zones: surface zone (SZ, 10–20%), middle zone (MZ, 40–60%) and deep zone (DZ, almost 30%)12. The degeneration of AC, usually starting from SZ to DZ1, may result in joint pain and disability1,12. The material properties of AC are altered significantly with the progression of OA, including the depletion of proteoglycan, degradation of collagen fibre and disorganisation of the fibrillar direction12,13,14,15. Due to the above changes, the mechanical properties of AC would become softer in compression and weaker in tension3,12. In addition, the water content and the permeability of AC would be elevated12, which indicates the reduction in fluid pressurisation and the load support capability of AC.

Recently, the finite element (FE) method has been widely adopted to investigate the biomechanical behaviours of the knee or AC16,17,18, as it is challenging to obtain the biomechanical performance within the knee or AC through experimental methods. FE method could help to analyze the biomechanics of the tissue, including stresses and strains, non-invasively. In most knee FE models17,18,19, AC is simplified as a mono-phase material like isotropic elastic. However, the biomechanical behaviours of AC are strongly modulated by the fluid-solid interaction20, the depth-dependent properties21, and the collagen network22,23. Therefore, the depth-dependent fibril-reinforced biphasic AC model should be adopted to provide more realistic biomechanical information than the mono-phase AC model.

Several knee OA and UKA models constructed by the FE method could be reviewed3,5,22. Mononen et al. constructed a 2D knee joint to study the effect of the collagen network of degenerated AC on stress distribution22. Later, they extended their method to a 3D FE model and found out that OA in the medial femoral AC would increase the strains of the medial and lateral femoral AC5. In the study of Y. Dabiri and L.P. Li3, the depth-dependent fibril-reinforced biphasic AC model was constructed, and the material properties were adjusted to construct the degenerated AC model in the medial compartment. However, only a tiny femoral vertical displacement (0.1 mm) was applied to their model, which could not represent the physiological loads within the joint during daily activity. In recent years, Mononen et al. developed cartilage degeneration algorithms to predict proteoglycan loss and collagen degeneration in OA knees under physiological loads9,24. However, the above research works did not adopt the actual biphasic contact conditions. The fluid flow of the contact region would depend on the fluid pressure difference across the interface, and the free-draining boundary was implemented in the non-contacting area25,26. In addition, the biomechanical changes in the healthy lateral compartment of the medial knee OA model have not been well quantified in previous studies3,5,9, as they paid more attention to the degenerated medial compartment AC. As for UKA models, AC was constructed using mono-phase material using the FE method to study the biomechanics or kinematics of the knee with different implant positions and designs4,17,27. Up to now, AC has not been represented using fibril-reinforced biphasic material in UKA models16,21,23.

To sum up, the potential risks of OA progression in the lateral compartment during the progression of medial knee OA and after medial UKA surgery remain to be quantified under real biphasic contact conditions. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the biomechanical changes of lateral compartment AC during the progression of medial knee OA and after medial UKA surgery using the FE method.

Materials and methods

Healthy knee model

A right knee joint of a 70-year-old 77.1 kg female donor from the Open Knee Project28, verified in the previous study29, was adopted in this study. Magnetic resonance images of this knee joint at full extension position were captured by a 1.0 Tesla extremity scanner28. The geometric model of the knee joint, including femur, tibia, AC, menisci and ligaments, was reconstructed, as shown in Fig. 1.

The bones were meshed using quadrilateral shell elements, while the other tissues meshed using hexahedral elements. With the mesh in use, all models’ changes in the peak contact pressure and fluid pressure were less than 5% by doubling the mesh density. The final edge length of the hexahedral element used was within the range of 0.5–1.0 mm.

As for the material of bone and AC, the femur and tibia were considered rigid as the bone’s stiffness is much higher than other tissues29. AC was defined as a fibril-reinforced biphasic material23, with Neo-Hookean nonlinear material as its non-fibril matrix.

The strain-energy function (W) of neo-Hookean material was defined as formulated30:

where J is the relative volume (determinant of deformation gradient); I1 is the first invariant of the right Cauchy-Green deformation tensor; \(\mu\) and \(\lambda\) are the Lamé parameters, which are calculated by Poisson’s ratio v and Young’s modulus E:

The fibrillar strain-energy function was defined as followed30,31:

where \(\:\xi\:\) represents the measure of the fibrillar modulus, and the elasticity of the fibre at the origin stage is \(\:4\xi\:\)32; \(\alpha\) denotes the coefficient of the exponential argument, and \(\beta\) is the power of the exponential argument; \({I_n}\) denotes the square of the fibre stretch.

When \(\alpha\)→ 0, a power law would produce in Eqs. (3),

In order to convert the stress from compression to tension continuously, \(\alpha\)= 0 and \(\beta\) = 2 were selected in this study21,30.

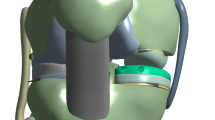

Moreover, the properties of AC were considered as depth-dependent based on previous studies21,33,34. For example, Young’s modulus33, Poisson’s ratio34, water volume fraction35 and permeability34,36,37 (Table 1) are depth-dependent. The fibrillar direction also varied across the depth of AC, which had been used and validated in previous studies23. As shown in Fig. 1, fibres were (1) parallel to the surface of AC, and oriented according to the split-line in the SZ; (2) equally applied to three orthogonal directions to construct the randomly distributed fibrillar pattern in the MZ; (3) perpendicular to the AC surface in the DZ.

The permeability of AC (k) was strain-dependent38, and it decreased exponentially as follows38:

where k0 describes the initial permeability in the original state; \({\varphi _s}\) denotes the solid volume fraction of AC; M is the exponential strain-dependent constant, and \({\alpha _e}\) denotes the power-law exponent. According to the previous experiment38, M = 4.638 and \({\alpha _e}\) = 0.0848 were selected to produce strain-dependent permeability.

As for the material of the meniscus, it was also defined as fibril-reinforced biphasic material29. The fibres within the meniscus were oriented in circumferential and radial directions.

As for the material of ligaments, they were considered as fibril-reinforced material, with Mooney-Rivlin nonlinear material as the non-fibril matrix (Table 2). The strain-energy function of the ligament was defined as follows28,30,39,40:

where \(\:{C}_{1}\) and \(\:{C}_{2}\) represent Mooney-Rivlin constants; \(\:{C}_{3}-{C}_{6}\) represent fibrillar function constants; \(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{I}}_{1}\) and \(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{I}}_{2}\) are first and second invariants of the deviatoric right Cauchy-Green deformation tensor, respectively; Ei is the exponential integral function; K is the Bulk modulus; F is the strain energy density component; \(\:\stackrel{\sim}{\lambda\:}\) is the deviatoric part of the stretch along the fibrillar direction and \(\:{{\uplambda\:}}_{m}\) is the straightened fibre stretch.

Medial knee OA model

To simulate the progression of medial knee OA, the material properties, as well as the geometries of medial AC and medial meniscus (MM), were modified according to previous studies1,2,3,22. As shown in Table 1, Young’s modulus of the non-fibrillar matrix and the fibrillar modulus were decreased by 70% and 75%, respectively; the permeability was increased by 70%; the solid volume fraction was reduced by 5%; the fibres were randomly distributed in degenerated AC3,41,42. The changes in material properties of degenerated MM were similar to that of degenerated AC2. Besides, in the advanced OA situation, the medial AC zones and MM were removed to simulate the worn-out compartment1,2.

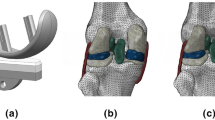

The progression of medial knee OA were classified according to the Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) histopathological grading system1: healthy (OARSI 0–1), early OA (OARSI 2–3) and advanced OA (OARSI 4-4.5). Model 1 (OARSI 0–1): healthy knee; Model 2 (OARSI 2): the degeneration only occurred in medial SZ; Model 3 (OARSI 3): the degeneration occurred in medial SZ and MZ; Model 4 (OARSI 4): the degeneration occurred in medial MD, DZ and MM, and meanwhile, medial SZ was removed to simulate the worn-out AC; Model 5 (OARSI 4.5): the degeneration occurred in medial DZ, meanwhile, medial SZ, MZ and MM were removed to simulate an extreme OA case. During the progression of medial knee OA, the softness and wear of cartilage and meniscus can lead to a slightly varus knee. All the cases were summarised in Table 3 and presented in Fig. 2.

UKA model

The UKA model was established based on a fixed-bearing UKA system. The femoral component and tibial tray sizes were chosen according to the dimensions of the femur and tibia. During medial UKA, the knee joint was realigned by implanting the UKA system to an ideal position supervised by two experienced UKA surgeons (Fig. 2). The heights of the femoral compartment and tibial tray coincided with the bone contour of the initial healthy knee joint.

As for UKA component materials, the femoral component, tibial tray, and insert were made of cobalt-chromium-molybdenum alloy (CoCrMo), titanium alloy (Ti6Al4V) and ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene (UHMWPE), respectively (Table 4). They were modeled as linear elastic isotropic materials. The medial UKA model was denoted as Model 6.

Loading and boundary conditions

First, we validated the knee model. The vertical displacement of the femur and the contact pressure of the AC of Model 1 under 1000 N and 1500 N compressive loads were compared with previous experimental results (Tables 5 and 6). The tibia was fully fixed in all directions, and the rotation of the femur was fixed in the flexion-extension direction. The compressive loads were applied to the reference point of the femur, which was located at the position of 5 mm medial to the joint center. This 5 mm offset was based on the previous study29 and met the ISO standard (ISO 14243–1:2009) for the TKA wear test.

Second, the healthy knee, medial knee OA and medial UKA models were simulated. One whole gait cycle was simulated in Model 1. We compared the results with the maximum load-only scenario in this gait cycle. The speed of this gait cycle was one cycle per second. Simulating the maximum load in the gait cycle would save much computational time while providing less than 3% variations in the predicted stress and strain. So, due to the prolonged computational period required in biphasic contact models, only the maximum load during daily walking activity (ISO 14243–1:2009) was simulated. For the femur, the rotations in the flexion-extension direction and internal-external direction, and the translation in the anterior-posterior direction were adjusted to determine the corresponding position of the femur to the tibia based on the anatomical flexion axis and kinematics data (ISO 14243–1:2009)28. The maximum load of the gait cycle was normalized to three times body weight (3 BW) compressive load and applied to Models 1 to 6 in 0.01 s43.

All the models were analysed using FEBio44, and their mechanical outputs, such as stresses and strains, were analysed. The backside of the AC and the ends of the ligaments were fixed on bones. Meniscal attachments on the tibial plateau were modeled as linear springs with a total stiffness of 2000 N/mm at each horn45,46. In order to represent the bone cement in UKA models, the components were fully bonded to the bones4. The biphasic contacts between femoral AC and tibial AC and between AC and meniscus were assumed to be frictionless23. On the AC and menisci surfaces, fluid could flow between touching regions depending on the fluid pressure difference across the interface and flow out freely at the non-contacting area25,26,29. The contact between the articular surface of UKA components was set with a friction coefficient of 0.044.

Results

The vertical displacements of the femur under 1000 N and 1500 N loads were presented in Table 5, along with the results of previous experimental and computational studies. The vertical displacements of the femur in this study were in the range of existing experimental and computational studies.

The peak contact pressures of the AC on the medial and lateral compartments under 1000 N load were compared with the results in the literature (in Table 6). The comparison results show that the AC’s contact pressures on the medial and lateral compartments agree well with previous experimental and computational studies. In a seminal study investigating the biomechanical implications of collagen fiber orientation distribution of articular cartilage on knee joint response, peak contact stresses of 2.5 MPa were recorded under 700 N axial loading conditions50. The investigation employed identical computational modeling protocols derived from the Open Knee Project, ensuring direct methodological comparability with the present study.

The peak fluid pressure, effective solid stress, and compressive strain in the medial and lateral femoral cartilage compartments of Model 1 are shown in Fig. 3. The variation of fluid pressure and solid effective stress demonstrated variation patterns that closely followed the applied loading profile.

The fluid pressure of AC and the fluid diffusion within the AC in the coronal plane in Model 1 are shown in Fig. 4. The maximum fluid pressure was located in the medial compartment, with a maximum value of 9.56 MPa, as shown in Fig. 4a. In Fig. 4b, the direction of fluid diffusion depended on the fluid pressure difference, and the fluid could flow across the contact interface.

The comparisons of the effective solid stress (= Von Mises Stress) of the lateral femoral and tibial AC in Models 1 to 6 under 3 BW load are shown in Fig. 5. The maximum effective stresses were increased during the progression of medial knee OA. In early medial knee OA (OARSI 2–3), less than a 2% increase in the maximum effective solid stress can be observed in Models 2 and 3. However, in advanced medial knee OA (OARSI 4.5), the maximum effective solid stress of Model 5 was increased markedly by 6.5%. After medial UKA surgery, the maximum effective solid stress of Model 6 was the same as that of Model 5, but a significant decrease in stress in the SZ of Model 6 can be observed.

The comparisons of the compressive strain of the lateral femoral AC in the axial plane and the coronal plane in Models 1 to 6 under 3 BW load are shown in Fig. 6. The maximum compressive strain was also increased during the progression of medial knee OA. In early medial knee OA (OARSI 2–3), less than a 2% increase in the maximum compressive strain was shown in Models 2 and 3. However, in advanced medial knee OA (OARSI 4.5), the maximum compressive strain of Model 5 was increased by 4.3%. After medial UKA surgery, the maximum compressive strain of Model 6 was similar to that of Model 4.

The maximum shear stress and the maximum principal stress of the lateral compartment AC are shown in Fig. 7. In all models, the stresses were increased along with the depth of AC. The stresses were also increased during the progression of medial knee OA. In early medial knee OA (OARSI 2–3), only a slight increase in the stresses can be observed in Models 2 and 3. However, in advanced medial knee OA (OARSI 4-4.5), the stresses in the SZ, MZ, and DZ increased markedly. For example, the maximum principal stress in the DZ of Model 5 was increased by 7.0% and higher than the average yield stress56. After medial UKA surgery, the stresses in the DZ of Model 6 were similar to the stresses in the DZ of Model 5. However, a considerable decrease in the stresses in the SZ and MZ of Model 6 can be observed.

The maximum shear strain and the maximum principal strain of the lateral compartment AC are shown in Fig. 8. In all models, the strains in the SZ were higher than the strains in the MZ and DZ. The maximum strains in the SZ were also increased during the progression of medial knee OA. In early medial knee OA (OARSI 2–3), the strains of the lateral compartment AC were similar to the results of the healthy knee (OARSI 0–1). However, in advanced medial knee OA (OARSI 4-4.5), the strains in the SZ increased considerably. For example, the maximum principal strain in the SZ of Model 5 was increased by 22.2% and became higher than the average yield strain56. After medial UKA surgery, the strains in the SZ of Model 6 decreased dramatically, becoming similar to the healthy knee results (OARSI 0–1).

Discussion

In this study, the healthy knee, medial knee OA, and medial UKA models were constructed and simulated under actual biphasic contact conditions. The biomechanical behaviours of the lateral compartment AC during the progression of medial knee OA and after medial UKA surgery were studied.

Before constructing the medial knee OA and UKA models, the validity of the fibril-reinforced biphasic knee model was tested by comparing the predicted results in this study using data from previous experimental and computational studies. The displacement of the femur and the peak contact pressure of the AC were widely adopted to prove the reasonability of the models in many computational studies29,54, as they represent the overall stiffness of the knee joint and local congruity of the two opposing surfaces48, respectively. Although more accurate AC model validation (including parameter variation) needs to be further developed in future studies, the parameter variation of the AC model has a limited effect on this study’s conclusion. Because all models’ initial parameters are consistent, and the changes in material properties of different OA models are modified based on the initial values. If parameter variation exists, for example, when the elastic modulus is large, the biomechanical results of all models (such as stress or strain) will increase or decrease accordingly, so the deviation of the model parameters has little impact on the conclusions of this paper. Furthermore, our knee model successfully adopted the actual biphasic contact conditions. As shown in Fig. 4, the fluid diffusion of the contact area would depend on the fluid pressure difference across the interface, and the free-draining boundary was implemented in the non-contacting area21. In addition, gradually reduced fluid pressurisation in medial tibial AC can be observed during the progression of medial knee OA, which is also in good agreement with the previous study3.

The comparisons between the healthy knee and the medial knee OA showed that the effect of medial knee OA on the biomechanics of lateral compartment AC was minimal at the early OA stage but became marked at the late OA stage. In early medial knee OA models (OARSI 2–3), the stress and strain of the lateral compartment AC were similar to the results of the healthy knee model. However, in the advanced medial knee OA model (OARSI 4.5), the stress of the lateral compartment AC was increased markedly. According to previous studies8,9,57, excessive local stress could be the reason for tissue fibrillation and chondrocytes’ death. In addition, the maximum principal strain of the lateral compartment AC in advanced medial knee OA model (OARSI 4.5) was higher than the average yield strain56, which might result in collagen degeneration and superficial disruptions56,58. Therefore, the increasing stress and strain of the lateral compartment AC in advanced medial knee OA (OARSI 4.5) might be the potential risk of OA development in the lateral compartment5.

After medial UKA surgery, biomechanics of the lateral compartment AC altered markedly. Firstly, the strain of the lateral compartment AC in UKA models was considerably reduced compared with the untreated advanced medial knee OA model (OARSI 4.5). Secondly, the stresses in the SZ and MZ were reduced. Overall, although the maximum stresses in the DZ remained similar to those of the advanced medial knee OA model, other biomechanical behaviours, such as the maximum stresses and strains in the SZ of the lateral compartment AC, were improved after medial UKA surgery. Therefore, medial UKA surgery can help to lower the risks of OA progression in the lateral compartment during the advanced medial knee OA stage.

In our study, three main innovations are noteworthy. Firstly, the present study adopted the actual biphasic contact conditions, which have not been achieved in other OA knee joint models3,5,9,22. Secondly, medial UKA models with fibril-reinforced biphasic AC and meniscus in lateral compartment AC were simulated for the first time. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, fibril-reinforced biphasic AC and meniscus have not been implemented in previous UKA models. Thirdly, in most previous models of degenerated AC3,5,22, the matrix loss of AC and meniscus at the end-stage of the medial compartment was not considered. But in the current study, both the mechanical properties and geometries of medial AC and MM were modified to simulate the progression of medial knee OA based on OARSI Osteoarthritis Cartilage Histopathology Assessment System of AC1 and histological assessment of meniscus2.

Some limitations still exist in the present study. First, we only simulated the maximum load during the gait instead of a whole gait cycle. Because biphasic knee joint models require a prolonged simulation period, focusing on the maximum load during the gait could significantly reduce computational costs. Since this paper aims to investigate the potential risk of OA progression in the lateral compartment under actual biphasic contact conditions and walking is the most frequent activity during one day, the maximum loading stage in a gait cycle is the most interesting. In this study, parameters including maximum stress and strain of AC occur at the peak loading stage in one gait cycle, which agrees well with the previous study45. However, if higher demanding loading conditions such as climbing stairs or getting up out of a chair are considered, our models’ predicted stress and strain would nonlinearly increase3,59. Under these situations, the biomechanical changes and the risk of OA progression in the lateral compartment AC might be enlarged. Second, the anisotropic permeability reported in other AC models3,21, which affects the time-dependent behaviour of AC, was not considered. As prolonged loading is not within the areas of interest in the current study and the time-dependent behaviour of AC is minimal over short-term loading60, the effect of the anisotropic permeability on our predicted results can be neglected61. Third, this study did not consider the degenerated lateral compartment AC in advanced medial knee OA. This study assumed that the lateral compartment AC was healthy in all models to control the variables better, as the changes in the parameters of the medial compartment AC and the lateral compartment AC would affect the mechanical results of the lateral compartment AC at the same time. In other words, this experimental setting could help investigate the biomechanical effects of the progression of medial knee OA on lateral compartment AC. Previous studies5 showed that increased strain could be found in degenerated AC. Therefore, it is inferred that when the degenerated lateral compartment AC was modeled in advanced medial knee OA, the biomechanical results of the lateral compartment AC would worsen, which does not affect the conclusions of this study. Fourth, this study did not model the tibiofemoral friction increases in degenerated joints. The previous study showed that the friction coefficient magnitude had no appreciable effect on the mechanical behaviours of the AC, such as the contact pressure62. Therefore, the biphasic contact interface was modeled as frictionless in this study. Fifth, this study utilized a single geometric model of the knee joint. Given that geometric characteristics of knee models are recognized as critical factors influencing cartilage biomechanics, the use of a single configuration inevitably introduces uncertainty in the evaluation results, constituting a limitation of this work. Future studies should investigate models with diverse geometric structures55. Sixth, the model employed loading conditions and kinematic data derived exclusively from ISO-standard walking gait. This singular activity pattern represents another limitation, as loading conditions and gait parameters influence tissue response through multiple pathways. Beyond direct load magnitude effects, critical factors including load application position, joint alignment, and kinematic patterns can substantially alter articular cartilage stress distribution. Future investigations should systematically explore how varying loading protocols and kinematic patterns influence articular cartilage stress response mechanisms63. Moreover, the effect of OA progression on bone was not considered in this study, as this study mainly focused on the degenerated cartilage caused by trauma. In order to control the variables better, the same bone was adopted in all models. The shape change of the joint resulted from the OA progression, and the mechanical properties of the subchondral bone would be considered in our future modelling study. Finally, the validation of the model only in the fully extended position is insufficient, which is also a major challenge in the validation of biphasic joint models63. Both scientific experimental design and parameterized numerical modeling can provide certain solutions.

To sum up, despite the above limitations, the models developed in this study provide in-depth information on the function, progressive mechanism of medial knee OA, and biomechanical outcome of unicompartmental replacement in the knee.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the healthy knee, medial knee OA, and medial UKA models under actual biphasic contact conditions were constructed to study the biomechanical behaviours of the lateral compartment AC during the progression of medial knee OA and after medial UKA surgery. It was found that the biomechanics of the lateral compartment AC in early medial knee OA (OARSI 2–3) were similar to the results of the healthy knee. In advanced medial knee OA (OARSI 4.5), the increasing stress and strain of the lateral compartment AC might increase the potential risk of OA development in the lateral compartment. After medial UKA surgery, some of the biomechanical behaviours of the lateral compartment AC were improved. Therefore, medial UKA surgery might help to lower the risks of OA progression in the lateral compartment during the advanced medial knee OA stage. The knee is a complex biomechanical system in which compartments should be accounted for when investigating partial degeneration and replacement. The approach of modelling medial UKA models with fibril-reinforced biphasic AC in this study can be adopted to provide realistic predicted results in future UKA studies.

The geometry of a right knee joint from the Open Knee Project (https://simtk.org/home/openknee)28 was reconstructed in the medical imaging software Mimics (Version 21.0, www.materialise.com) (a); depth-dependent fibrillar distributions pattern of AC (b); natural split-line patterns in the surface zone (c).

The progression models of medial knee OA and UKA models were analysed using FEBio (Version 2.9, www.febio.org), a fixed-bearing UKA system (Zimmer, Warsaw, IN, USA) was adopted in the UKA model. The green tissue denoted the healthy tissues and fibres, while the red tissue represented the degenerated tissues and fibres.

The maximum shear stress (a) and the maximum principal stress (b) of lateral compartment AC under 3 BW compressive load in Models 1 to 6. The Red line indicates the average yield stress based on the previous study56.

The maximum shear strain (a) and the maximum principal strain (b) of lateral compartment AC under 3 BW compressive load in Models 1 to 6. The Red line indicates the average yield strain based on the previous study56.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Pritzker, K. P. et al. Osteoarthritis cartilage histopathology: grading and staging. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 14, 13–29 (2006).

Pauli, C. et al. Macroscopic and histopathologic analysis of human knee menisci in aging and osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 19, 1132–1141 (2011).

Dabiri, Y. & Li, L. P. Altered knee joint mechanics in simple compression associated with early cartilage degeneration. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2013, 862903 (2013).

Innocenti, B. et al. Load sharing and ligament strains in balanced, overstuffed and understuffed UKA. A validated finite element analysis. J. Arthroplasty. 29, 1491–1498 (2014).

Mononen, M. E. et al. Effect of superficial collagen patterns and fibrillation of femoral articular cartilage on knee joint mechanics-a 3D finite element analysis. J. Biomech. 45, 579–587 (2012).

Moen, T. C., Laskin, W. & Puri, L. The lateral compartment in knees with isolated medial and patellofemoral osteoarthritis: a histologic analysis of articular cartilage. J. Arthroplasty. 26, 783–787 (2011).

Robertsson, O., Knutson, K., Lewold, S. & Lidgren, L. The Swedish knee arthroplasty register 1975–1997: an update with special emphasis on 41,223 knees operated on in 1988–1997. Acta Orthop. 72, 503–513 (2001).

Huang, W., Warner, M., Sasaki, H., Furukawa, K. S. & Ushida, T. Layer dependence in strain distribution and chondrocyte damage in Porcine articular cartilage exposed to excessive compressive stress loading. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 112, 104088 (2020).

Mononen, M. E., Tanska, P., Isaksson, H. & Korhonen, R. K. New algorithm for simulation of proteoglycan loss and collagen degeneration in the knee joint: data from the osteoarthritis initiative. J. Orthop. Res. 36, 1673–1683 (2018).

Roemhildt, M. L. et al. Effects of increased chronic loading on articular cartilage material properties in the Lapine tibio-femoral joint. J. Biomech. 43, 2301–2308 (2010).

Voinier, D. et al. Using cumulative load to explain how body mass index and daily walking relate to worsening knee cartilage damage over two years: the MOST study. Arthritis Rheumatol. (Hoboken NJ). 72, 957–965 (2020).

Mow, V. C., Ratcliffe, A. & Poole, A. R. Cartilage and diarthrodial joints as paradigms for hierarchical materials and structures. Biomaterials 13, 67–97 (1992).

Ebrahimi, M. et al. Structure-Function relationships of healthy and Osteoarthritic human tibial cartilage: experimental and numerical investigation. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 48, 2887–2900 (2020).

Mukherjee, S., Nazemi, M., Jonkers, I. & Geris, L. Use of computational modeling to study joint degeneration: A review. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 8, 93 (2020).

Ebrahimi, M. et al. Elastic, dynamic viscoelastic and Model-Derived Fibril-Reinforced poroelastic mechanical properties of normal and Osteoarthritic human femoral condyle cartilage. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 49, 2622–2634 (2021).

Sajjadinia, S. S., Carpentieri, B. & Holzapfel, G. A. A backward pre-stressing algorithm for efficient finite element implementation of in vivo material and geometrical parameters into fibril-reinforced mixture models of articular cartilage. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 114, 104203 (2021).

Koh, Y. G. et al. Anatomy-mimetic design preserves natural kinematics of knee joint in patient-specific mobile-bearing unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 28, 1465–1472 (2020).

Ding, K. et al. Finite element analysis of Biomechanical effects of residual varus/valgus malunion after femoral fracture on knee joint. Int. Orthop. 45, 1827–1835 (2021).

Kwon, H. M., Kang, K. T., Kim, J. H. & Park, K. K. Medial unicompartmental knee arthroplasty to patients with a ligamentous deficiency can cause biomechanically poor outcomes. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 28, 2846–2853 (2020).

Mow, V. C., Kuei, S. C., Lai, W. M. & Armstrong, C. G. Biphasic creep and stress relaxation of articular cartilage in compression? Theory and experiments. J. Biomech. Eng. 102, 73–84 (1980).

Lin, W., Meng, Q., Li, J., Chen, Z. & Jin, Z. The effect of highly inhomogeneous biphasic properties on mechanical behaviour of articular cartilage. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 206, 106122 (2021).

Mononen, M. E. et al. Alterations in structure and properties of collagen network of Osteoarthritic and repaired cartilage modify knee joint stresses. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 10, 357–369 (2011).

Li, J. et al. The influence of the representation of collagen fibre organisation on the cartilage contact mechanics of the hip joint. J. Biomech. 49, 1679–1685 (2016).

Mononen, M. E., Tanska, P., Isaksson, H. & Korhonen, R. K. A novel method to simulate the progression of collagen degeneration of cartilage in the knee: data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Sci. Rep. 6, 21415 (2016).

Ateshian, G. A., Maas, S. & Weiss, J. A. Finite element algorithm for frictionless contact of porous permeable media under finite deformation and sliding. J. Biomech. Eng. 132, 061006 (2010).

Pawaskar, S. S., Fisher, J. & Jin, Z. Robust and general method for determining surface fluid flow boundary conditions in articular cartilage contact mechanics modeling. J. Biomech. Eng. 132, 031001 (2010).

Danese, I., Pankaj, P. & Scott, C. E. H. The effect of malalignment on proximal tibial strain in fixed-bearing unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: A comparison between metal-backed and all-polyethylene components using a validated finite element model. Bone Joint Res. 8, 55–64 (2019).

Sibole, S. et al. Open Knee: A three-dimensional finite element representation of the knee joint. 34th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Biomechanics. Providence, RI (2010).

Meng, Q., Jin, Z., Wilcox, R. & Fisher, J. Computational investigation of the time-dependent contact behaviour of the human tibiofemoral joint under body weight. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. H. 228, 1193–1207 (2014).

Maas, S., Rawlins, D., Weiss, J. A. & Ateshian, G. A. FEBio Theory Manual – Version 2.9: University of Utah (Utah., 2019).

Ateshian, G. A., Rajan, V., Chahine, N. O., Canal, C. E. & Hung, C. T. Modeling the matrix of articular cartilage using a continuous fiber angular distribution predicts many observed phenomena. J. Biomech. Eng. 131, 061003 (2009).

Meng, Q. et al. The effect of collagen fibril orientation on the biphasic mechanics of articular cartilage. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 65, 439–453 (2017).

Wahlquist, J. A. et al. Indentation mapping revealed poroelastic, but not viscoelastic, properties spanning native zonal articular cartilage. Acta Biomater. 64, 41–49 (2017).

Li, L. P., Buschmann, M. D. & Shirazi-Adl, A. A fibril reinforced nonhomogeneous poroelastic model for articular cartilage: inhomogeneous response in unconfined compression. J. Biomech. 33, 1533–1541 (2000).

Shapiro, E. M., Borthakur, A., Kaufman, J. H., Leigh, J. S. & Reddy, R. Water distribution patterns inside bovine articular cartilage as visualized by 1H magnetic resonance imaging. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 9, 533–538 (2001).

Maroudas, A., Bullough, P., Swanson, S. A. V. & Freeman, M. A. R. The permeability of articular cartilage. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. Volume. 50-B, 166–177 (1968).

Krishnan, R., Park, S., Eckstein, F. & Ateshian, G. A. Inhomogeneous cartilage properties enhance superficial interstitial fluid support and frictional properties, but do not provide a homogeneous state of stress. J. Biomech. Eng. 125, 569–577 (2003).

Holmes, M. H. & Mow, V. C. The nonlinear characteristics of soft gels and hydrated connective tissues in ultrafiltration. J. Biomech. 23, 1145–1156 (1990).

Pena, E., Calvo, B., Martinez, M. A. & Doblare, M. A three-dimensional finite element analysis of the combined behavior of ligaments and menisci in the healthy human knee joint. J. Biomech. 39, 1686–1701 (2006).

Gardiner, J. C. & Weiss, J. A. Subject-specific finite element analysis of the human medial collateral ligament during valgus knee loading. J. Orthop. Res. 21, 1098–1106 (2003).

Boschetti, F. & Peretti, G. M. Tensile and compressive properties of healthy and Osteoarthritic human articular cartilage. Biorheology 45, 337 (2008).

Korhonen, R. K. et al. Fibril reinforced poroelastic model predicts specifically mechanical behavior of normal, proteoglycan depleted and collagen degraded articular cartilage. J. Biomech. 36, 1373–1379 (2003).

Schipplein, O. D. & Andriacchi, T. P. Interaction between active and passive knee stabilizers during level walking. J. Orthop. Res. 9, 113–119 (1991).

Maas, S. A., Ellis, B. J., Ateshian, G. A. & Weiss, J. A. FEBio: finite elements for biomechanics. J. Biomech. Eng. 134, 011005 (2012).

Halonen, K. S., Mononen, M. E., Jurvelin, J. S., Toyras, J. & Korhonen, R. K. Importance of depth-wise distribution of collagen and proteoglycans in articular cartilage–a 3D finite element study of stresses and strains in human knee joint. J. Biomech. 46, 1184–1192 (2013).

Haut Donahue, T. L., Hull, M. L., Rashid, M. M. & Jacobs, C. R. How the stiffness of meniscal attachments and meniscal material properties affect tibio-femoral contact pressure computed using a validated finite element model of the human knee joint. J. Biomech. 36, 19–34 (2003).

Walker, P. S. & Erkman, M. J. The role of the menisci in force transmission across the knee. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 109, 184–192 (1975).

Kurosawa, H., Fukubayashi, T. & Nakajima, H. Load-Bearing mode of the Knee-Joint - Physical behavior of the Knee-Joint with or without menisci. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. :283–290. (1980).

Shrive, N. G., O’Connor, J. J. & Goodfellow, J. W. Load-bearing in the knee joint. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 131, 279–287 (1978).

Raju, V. & Koorata, P. K. Computational assessment on the impact of collagen fiber orientation in cartilages on healthy and arthritic knee kinetics/kinematics. Med. Eng. Phys. 117. (2023).

Fukubayashi, T. & Kurosawa, H. The contact area and pressure distribution pattern of the knee. A study of normal and Osteoarthrotic knee joints. Acta Orthop. Scand. 51, 871–879 (1980).

Marzo, J. M. & Gurske-DePerio, J. Effects of medial meniscus posterior Horn avulsion and repair on tibiofemoral contact area and peak contact pressure with clinical implications. Am. J. Sports Med. 37, 124–129 (2009).

Allaire, R., Muriuki, M., Gilbertson, L. & Harner, C. D. Biomechanical consequences of a tear of the posterior root of the medial meniscus. Similar to total meniscectomy. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 90, 1922–1931 (2008).

Bendjaballah, M. Z., Shirazi-Adl, A. & Zukor, D. J. Biomechanics of the human knee joint in compression: reconstruction, mesh generation and finite element analysis. Knee 2, 69–79 (1995).

Paz, A. et al. A novel knee joint model in febio with inhomogeneous fibril-reinforced biphasic cartilage simulating tissue mechanical responses during gait: data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Comput. Methods Biomech. BioMed. Eng. 26, 1353–1367 (2022).

Danso, E. K., Honkanen, J. T., Saarakkala, S. & Korhonen, R. K. Comparison of nonlinear mechanical properties of bovine articular cartilage and meniscus. J. Biomech. 47, 200–206 (2014).

Tanska, P., Venalainen, M. S., Erdemir, A. & Korhonen, R. K. A multiscale framework for evaluating three-dimensional cell mechanics in fibril-reinforced poroelastic tissues with anatomical cell distribution - Analysis of chondrocyte deformation behavior in mechanically loaded articular cartilage. J. Biomech. 101, 109648 (2020).

Hosseini, S. M., Wilson, W., Ito, K. & van Donkelaar, C. C. A numerical model to study mechanically induced initiation and progression of damage in articular cartilage. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 22, 95–103 (2014).

Felson, D. T. & Chaisson, C. E. Understanding the relationship between body weight and osteoarthritis. Baillieres Clin. Rheumatol. 11, 671–681 (1997).

Li, J., Stewart, T. D., Jin, Z., Wilcox, R. K. & Fisher, J. The influence of size, clearance, cartilage properties, thickness and hemiarthroplasty on the contact mechanics of the hip joint with biphasic layers. J. Biomech. 46, 1641–1647 (2013).

Gu, K. B. & Li, L. P. A human knee joint model considering fluid pressure and fiber orientation in cartilages and menisci. Med. Eng. Phys. 33, 497–503 (2011).

Brown, T. D. & DiGioia Iii, A. M. A contact-coupled finite element analysis of the natural adult hip. J. Biomech. 17, 437–448 (1984).

Li, J. et al. Computational modelling of articular joints with biphasic cartilage: recent advances, challenges and opportunities. Med. Eng. Phys. ;126. (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [12202074, 52035012], the Natural Science Foundation of Shaanxi Province of China [2023-JC-YB-402], and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, CHD [300102254205].

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [12202074, 52035012], the Natural Science Foundation of Shaanxi Province of China [2023-JC-YB-402], and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, CHD [300102254205].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J. Z. and W.J.L. wrote the main manuscript, Z.X. C and Z.M.J revised the manuscript, W.J.L designed and finished the analysis, and J.Y.L provided the finite element model guidance. All the authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, J., Lin, W., Li, J. et al. Biomechanical effects of medial osteoarthritis progression and UKA on knee lateral compartment using fibril-reinforced biphasic material in finite element study. Sci Rep 15, 27332 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12285-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12285-z