Abstract

Accurate scientific predicting of water requirements for protected agriculture crops is essential for informed irrigation management. The Penman-Monteith model, endorsed by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), is currently the predominant approach for estimating crop water needs. However, the complexity of its numerous parameters and the potential for empirical parameter inaccuracies pose significant challenges to precise water requirement predictions. In this study, we introduce a novel water demand prediction model for greenhouse tomato crops that leverages multi-source data fusion. We employed the ExG (Excess Green) algorithm and the maximum inter-class variance method to develop an algorithm for extracting canopy coverage from image segmentation. Subsequently, Spearman correlation analysis was utilized to select the combination of canopy coverage and environmental data, followed by the random forest feature importance ranking method to identify the most optimal feature variables. We constructed average fusion, weighted fusion, and stacking fusion models based on RandomForest, LightGBM, and CatBoost machine learning algorithms to accurately predict the water requirements of greenhouse tomato crops. The results show that the stacking model has the best prediction effect, and the error is lower than that of RandomForest, LightGBM, CatBoost, Average fusion model and Weighted fusion model. The feature combination of Tmax, Ts, and CC, filtered using Spearman and RandomForest, demonstrated the lowest prediction errors, with reductions in MSE, MAE, and RMSE of over 4%, 14%, and 3%, respectively, compared to other parameter combinations. The R2 value increased by 1%, indicating enhanced reliability and generalization. This research comprehensively considered various factors, including environmental, soil, and crop growth conditions, that influence crop water requirements. By integrating image and environmental data, we developed a water requirement prediction model for greenhouse tomato crops based on the principles of decoupling and minimizing characteristic parameters, offering innovative technical support for scientific irrigation practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Facility horticulture is a modern agricultural production method that uses new production equipment, and management techniques to regulate the environmental parameters such as temperature, light, water, and fertilizer in greenhouses1,2. In greenhouse cultivation, by establishing a scientific water requirement prediction model, a deeper understanding of the growth patterns of greenhouse crops can be achieved, providing basis for scientific irrigation3.

Currently, the Penman-Monteith model, as advocated by FAO-56, serves as the standard for calculating crop water requirements and has been extensively applied to greenhouse crops including tomatoes, eggplants, and lettuce4,5,6,7. The model’s predictive power for crop water demand is derived from the multiplication of the reference crop evapotranspiration (ET0) by the crop coefficient (Kc). Consequently, the ease of acquisition and the reliability of these parameters—ET0 and Kc—are pivotal to the efficiency and accuracy of water requirement predicts. Jo et al.8 employed weighing sensors to monitor the actual transpiration rate, recording tomato crop weight changes at 10-minute intervals, and subsequently developed a water demand prediction model grounded in the established Penman-Monteith (P-M) formula and crop coefficient (Kc). Dong et al.9 conducted an analysis of the spatio-temporal patterns of reference evapotranspiration, temperature, relative humidity, and sunlight duration across China, introducing an innovative enhanced GWA algorithm (MDSL-GWA) designed to refine the empirical estimation of ET0. Despite its utility, the Penman-Monteith model’s broad application is constrained by the necessity to estimate elusive parameters such as aerodynamic resistance, which is integral to its input parameters but challenging to ascertain. Furthermore, the model’s critical calculation parameter (Kc) is often determined empirically and is subject to variation due to diverse climatic conditions and soil properties, leading to significant discrepancies in practical scenarios. Research indicates that the Mean Square Error (MSE) of Kc throughout the tomato’s growth cycle can range from 11.9 to 71.4%10, underscoring the need for more precise predictive tools in agricultural water management.

Therefore, with the advancement of computer technology, researchers have begun to propose methods that use machine learning to directly predict water requirements without the need to calculate ET0 and Kc separately. Dong et al.11 proposed a novel model for predicting crop evapotranspiration in the wheat-corn rotation system of the Loess Plateau in China (GWA-CNN-BiLSTM). This model is based on the Grey Wolf Algorithm and uses five parameters, including net solar radiation (R) and saturation vapor pressure deficit (VPD), for prediction. The model achieved a relative root mean square error (RRMSE) ranging from 8.4 to 41.5%. Fuentes et al.12 used micrometeorological data and artificial neural networks (ANN) for modeling actual evapotranspiration and energy balance estimation in vineyards, and the established model demonstrated high accuracy and performance, with a determination coefficient R2 of 0.97. Tunalı et al.13 employed ANN network to estimate the crop water requirements (ETc) of tomatoes, and compared it with the traditional Penman-Monteith model, finding that the ANN model improved the prediction accuracy for ETc by 30% compared to traditional methods. However, crop water requirements are affected by various factors such as the growth condition of the crop itself, environment, soil, representing a nonlinear and complex characteristic of change. Therefore, this study considers the acquisition of crop growth conditions through imagery and combines it with environmental data, adhering to the principle of decoupling and minimizing characteristic parameters, to propose a multi-source data fusion model for predicting the water requirements of greenhouse tomato crops, predicting the water requirements of greenhouse tomato crops with a small number of parameters. The main objectives include: (1) Using the super green algorithm and the maximum inter-class variance method, a tomato canopy coverage extraction algorithm based on image segmentation is proposed, overcoming the difficulty of traditional methods in large-area measurement; (2) Under the full consideration of crop, soil and environment, the optimal combination of feature variables was proposed based on the principle of reducing the correlation of feature parameters and minimizing the feature parameters, combined with Spearman correlation analysis and random forest feature importance ranking method.; (3) Fusion algorithm based on single machine learning algorithms is proposed to construct a water requirement prediction model for greenhouse tomato crops, and its reliability and generalization are verified.

Method

Data acquisition

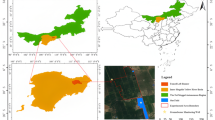

Data acquisition was conducted in the solar greenhouse of the National Precision Agriculture Research Demonstration Base in Xiaotangshan Town, Changping District, Beijing, China (East Longitude 116.46°, North Latitude 40.18°, altitude 50 m), which is a scientific research and test base of Beijing Academy of Agriculture and Forestry Sciences. Changping District of Beijing belongs to the temperate continental monsoon climate zone, which is the main area of solar greenhouse production in Beijing.

The cultivation experiment was carried out on tomato crops, using rectangular foam boxes as substrate slots, with dimensions of 100 cm*60 cm*40 cm, filled with coconut coir as the substrate. To ensure the vertical growth of tomato plants, the experiment utilized ropes to hang the plants from hanging scales to prevent environmental factors from affecting growth direction and leaf angles. Additionally, to avoid the impact of substrate moisture evaporation on the measurement of tomato water requirements, a transparent ground film was laid over the substrate surface. The data collected during the experiment included environmental data, image data, and crop water requirement data. The trial was divided into two seasons: the spring planting (from May 20, 2022, to July 22, 2022) and the autumn planting (from September 28, 2022, to January 6, 2023).

Environmental data were collected using greenhouse environmental sensors to measure air temperature (T, ℃), relative humidity (RH, %), soil temperature (Ts, ℃), light intensity (E, Lux), and CO2 concentration (ppm), with the sensors positioned approximately 20 cm above the crop. A photovoltaic total radiation sensor was used to collect cumulative light radiation data (Rn, Kj·m2·h−1) inside the greenhouse, placed 2 meters above the ground and 5 m away from the rear wall of the greenhouse. The technical specifications of the sensors are shown in Table 1. Environmental sensor data were acquired at 10-minute intervals and transmitted to the monitoring software via a wireless gateway. Image data were captured using an infrared mobile timed camera, the Forsafe H805, to obtain visible light images. The camera is placed in a fixed position directly above the tomato plant, giving a top-down view based on the planting layout of the tomato. The camera was set to take photos every hour, with an image resolution of 5200*3900 PPI (Pixels Per Inch).

The crop water requirement (ETc) is determined by measuring the substrate weight of tomato plants using a self-developed online substrate weighing system. The weighing system adopts LoRa wireless communication technology, the measurement error is ±0.03%, and the collection frequency is 10 minutes. In this study, an automatic controller tube was used to manage nutrient solution irrigation once a day to provide the required nutrients for plant growth, that is, irrigation was started 2 hours after the local sunrise time, and irrigation was ended when the matrix water content reached the upper limit (field moisture capacity), and the irrigation duration was less than 10 min, during which the crop water demand ETc was ignored. Therefore, the calculation of crop water demand ETc is shown in formula (1):

Among them, \({\text{B}}{{\text{W}}_{T1}}\) represents the substrate weight of the tomato plants at the previous time point, while \({\text{B}}{{\text{W}}_{T2}}\) denotes the substrate weight at the subsequent time point.

Data processing

Utilizing air temperature and humidity data gathered at 10-minute intervals, we derive six key parameters: the hourly/daily average air temperature (Tm), the peak air temperature (Tmax), the lowest air temperature (Tmin), the mean air humidity (RHm), the highest air humidity (RHmax), and the lowest air humidity (RHmin), employing both mean and extremum calculations. Concurrently, soil temperature and CO2 concentration, also measured every 10 min, inform the determination of the hourly/daily soil temperature (Ts) and CO2 concentration, achieved through averaging. Based on the light intensity and accumulated light radiation data collected every 10 min, the two parameters of hourly/daily light intensity (E) and accumulated light radiation (Rn) are calculated by cumulative calculation. The collection of actual visible light images of crops is complemented by a rigorous screening process to exclude images characterized by anomalous positioning, blurriness, or inadequate lighting conditions. For those individual time periods where sufficient and effective images could not be obtained after screening, we employed data augmentation techniques to supplement the dataset. This involved geometric transformations (such as rotation, flipping, and scaling) of high-quality images from adjacent times, as well as subtle adjustments to brightness and contrast to simulate different lighting conditions. Although these enhanced images were synthetic, they retained the core shape and texture features of the crops, effectively filling the data gap without introducing significant deviations.

Construction of a water requirement prediction model for greenhouse tomato crops

This paper proposes a multi-source data fusion model for predicting the water requirements of greenhouse tomato crops, based on images and environmental data. The model aims to calculate the water needs of greenhouse tomato crops with a minimal number of parameters and simple computations, providing a foundation for implementing appropriate irrigation measures. The model first establishes an algorithm for extracting the canopy coverage of greenhouse tomatoes based on image segmentation. It then combines canopy coverage with environmental data to select feature variable combinations with high correlation using Spearman’s correlation analysis method and chooses the optimal feature variables using the random forest feature importance ranking method. Finally, three types of fusion models (Average fusion, Weighted fusion, and Stacking) are constructed based on the RandomForest (RF), LightGBM, and CatBoost models. The greenhouse tomato crop water requirement prediction model is built through comparative experimental results. The model framework is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Canopy coverage extraction

The ExG (Excess Green) algorithm extracts green plant images effectively, suppressing shadows, withered grass, and soil images, making the plant images more prominent. However, the segmentation effect may be affected under strong light conditions. The ExG algorithm is used to perform grayscale processing on the images, as shown in Eq. (2).

In this context, G represents the pixel value of the green channel, R represents the pixel value of the red channel, and B represents the pixel value of the blue channel.

The Maximum Inter-Class Variance Method (Otsu Method)14 is an automatic threshold selection technique that does not require the manual setting of additional parameters. It segments the image into two parts: the target and the background, based on the selected threshold. The method calculates the maximum inter-class variance value corresponding to the pixel’s grayscale value, and the threshold at which the inter-class variance is maximized is considered the optimal threshold T. Then, the grayscale value of each pixel is compared with the threshold value T, and based on the comparison, the pixel is classified as either plant or background.

The total average grayscale value of an image is:

The inter-class variance is:

In this context, w0 is the proportion of plant pixel counts to the total image, u0 is the average grayscale value of the plant; w1 is the proportion of background pixel counts to the image, u1 is the average grayscale value of the background; where w0 + w1 = 1.

For the collected visible light images, the ExG algorithm is used for grayscale processing in combination with the Otsu method to segment tomato plants from the background. The segmentation effect is shown in Fig. 2. Observations from Fig. 2(a)-(d) indicate that the canopy coverage expands in tandem with the growth of the tomatoes.

Based on the segmented tomato plants, the proportion of green tomato plants out of all pixel points in the image is calculated, which represents the canopy coverage at this moment. Therefore, the calculation of daily canopy coverage is as shown in Eq. (5).

In this context, CC represents the daily canopy coverage, and CCi represents the canopy coverage at the i-th moment.

Optimal feature variable selection

When performing feature selection, a common approach is to calculate the significance of each characteristic and retain the most relevant features. However, during the direct ranking of feature importance, there is a risk that a feature may be mistakenly deemed less important and discarded due to high correlations among multiple feature variables, even though discarding one might not affect the outcome. In order to avoid this situation, Spearman correlation analysis15 was used in this paper to calculate the correlation coefficient among multiple variables, screen the combination of characteristic variables with high correlation, and set a threshold for the correlation coefficient. For each set of features whose correlation is above the threshold, only one feature variable is retained. When a duplicate variable is present in more than one combination, the duplicate variable is retained and other variables with a high correlation with this variable are removed. After the screening, the random forest feature importance ranking method is used to calculate the significance of each characteristic variable for predicting the water requirements of greenhouse tomato crops, and the optimal feature variables are selected based on a predefined importance threshold.

Data collected from environmental and image sensors, after preprocessing, yield 11 feature parameters as shown in Table 2.

Spearman’s correlation analysis is a method for calculating the correlation between two variables. The method is to rank the values of multiple variables and calculate the rank correlation (Spearman’s correlation coefficient) between them. Spearman’s correlation coefficient ranges from − 1 to 1. A value of −1 indicates a completely negative correlation, a value of 0 indicates no correlation between the two variables, and a value of 1 indicates a completely positive correlation. The calculation method for the correlation coefficient is shown in Eq. (6).

Where, n is the number of samples, and di is the difference between the position values of the i-th data pair.

The calculation steps for the Random Forest feature importance ranking method are as follows: (1) Train a random forest model on the training set; (2) Randomly shuffle the values of a certain feature variable, and then make predictions on the new dataset; (3) Calculate the loss function using the predicted values and the true values; the degradation in model performance after random shuffling represents the importance of the randomly shuffled column; (4) Restore the values of the feature variable that was randomly shuffled, repeat step (2) on the data of the next feature variable, and continue this process until the importance of each feature variable has been calculated.

Machine learning algorithm

RandomForest (RF)16 is an ensemble learning method that constructs multiple decision trees for classification or regression. In the training process, this method does not build a large decision tree with the entire training data set, but uses different subsets and feature attributes to build several small decision trees, each subset is built by randomly selected samples and feature attributes, and then merged into a more powerful model, as shown in Eq. (7). The RandomForest excels due to its capacity to enhance the model’s performance and introduce randomness during the training process, thereby improving the model’s generalization capability and reducing the risk of overfitting. The hyperparameter is set to: n_estimators=[10, 50, 100, 200, 400], max_depth=[None, 10, 20, 30, 50], min_samples_split=[2, 5, 10], min_samples_leaf=[1, 2, 4], max_features=[‘log2’,‘sqrt’]. After conducting experiments, the optimal combination of hyperparameters was obtained as follows: n_estimators=[400], max_depth=[20], min_samples_split=[2], min_samples_leaf=[1], max_features=[‘log2’].

In this context, \(\mathop y\limits^{ \wedge }\) represents the final prediction result of the RandomForest, T denotes the number of decision trees, and \({h_i}(x)\) is the prediction result of the i-th decision tree for the data point x.

LightGBM17 is a gradient-based decision tree algorithm that iteratively trains a series of weak classifiers (decision trees) and combines them into a strong classifier. The method principles can be divided into the following steps: (1) Initialize the model and related parameters. (2) Calculate the first and second order gradient information of the samples. (3) Train multiple decision trees sequentially, with each tree’s training objective being to minimize the loss function (usually the mean squared error or log loss function). (4) Update the model parameters using gradient descent to reduce the value of the loss function. (5) Repeat steps (3) and (4) until the specified number of iterations is reached or the model performance meets the threshold to stop. The hyperparameter is set to: objective = regression, metric = mse, num_leaves = 20, learning_rate = 0.1, feature_fraction = 0.9.

CatBoost18 is a gradient boosting decision tree-based machine learning algorithm that excels at handling datasets with a large number of categorical features. Unlike traditional gradient boosting algorithms, CatBoost does not require one-hot encoding for categorical features; instead, it directly uses these features for training, thus avoiding information loss and increased computational complexity. The formula is shown in Eq. (8). The hyperparameter is set to: iterations = 4, learning_rate = 1, depth = 4.

In this context, \(\mathop y\limits^{ \wedge }\) represents the final prediction result of CatBoost, T denotes the number of decision trees, \({\gamma _i}\) is the weight of the i-th decision tree, and \(h(x;{\delta _i})\) is the prediction result of the i-th decision tree for the data point x.

The averaging method combines the prediction results of multiple models for classification or regression. The core idea is to consider all model predictions as equally important and calculate their arithmetic mean as the final prediction. In this paper, an averaging fusion model is constructed based on the integration of three models: RandomForest, LightGBM, and CatBoost, as shown in Eq. (9), where F represents the final prediction result; n represents the number of models, which is 3 in this case; \({y_i}\) denotes the prediction result of the i-th model.

Weighted averaging19 is a method for classification or regression that assigns different weights to the prediction results of each model. The core idea is to allocate weights based on the performance or confidence of each model, with better-performing models receiving higher weights. In this paper, the weights are determined using the models’ MSE, where the weight is inversely proportional to the MSE. The smaller the model’s MSE, the greater the weight. The formula is shown in Eq. (10), where \({w_i}\) represents the weight assigned to the i-th model, with the sum of weights equaling 1.

Stacking20 is an advanced ensemble learning technique that constructs a new model, known as a meta-model, by integrating the predictions of multiple base models. In this study, we employed a stacking approach where the predictions from three base models (Random Forest, LightGBM, and CatBoost) were used as input features to train a meta-model. Specifically, we used Linear Regression as the meta-learner to combine these predictions. The core idea is to leverage the complementary strengths of diverse base models by learning their prediction patterns through the meta-model, which can enhance overall predictive performance. This approach significantly improves the model’s generalization capability by capturing complex relationships among base model predictions and reducing systematic errors.

Experimental environment

The training environment for this study is CPU: i7-12700 F 2.10 GHz, GPU: RTX 3060Ti, operating system: 64-bit, RAM: 16 GB. The model uses Python language. The Python version and the various versions of the environment packages used in this article are as follows: Python 3.9, numpy 2.0.2, pandas 2.3.0, scikit-learn 1.6.1, matplotlib 3.9.4.

Evaluation index

This study employed four common statistical metrics: Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Mean Squared Error (MSE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), and Coefficient of Determination (R2).

In this context, n is the total count of predict outcomes, \(\mathop {\hat {y}}\nolimits_{i}\) represents the predicted value, \(\mathop y\nolimits_{i}\) is the actual value, and \(\mathop {\bar {y}}\nolimits_{i}\)represents the average value.

Results and analysis

Different model results of multiple parameter combinations

For the daily data of spring-season tomatoes, the feature correlation heatmap after Spearman correlation analysis is shown in Fig. 3(a). Feature combinations with an absolute correlation value above 0.8 include: (Tm, Ts), (RHmax, RHm), (RHm, RHmin), (Rn, E). Based on the strongly correlated feature combinations mentioned above, and following the principle of using fewer feature input parameters, seven feature parameters were selected: Tmax, Tmin, RHm, Ts, Rn, CO2, and CC. After analyzing the feature correlations, we performed a random forest feature importance ranking on seven feature parameters, namely Tmax, Tmin, RHm, Ts, Rn, CO2, and CC. The results are shown in Fig. 3(b). It can be seen that Tmax has the greatest impact on tomato ETc, followed by Ts, while RHm has the smallest impact on tomato ETc. If only five parameters are chosen, then Tmax, Ts, CC, Tmin, and CO2 can be selected. If only three parameters are chosen, then Tmax, Ts, and CC can be selected.

Table 3 presents the four parameter combinations used for model construction. The parameter combination without feature selection includes all 11 feature parameters, namely Tmax, Tm, Tmin, RHmax, RHm, RHmin, Ts, Rn, E, CO2, and CC. The parameter combination after Spearman feature selection includes 7 feature parameters: Tmax, Tmin, RHm, Ts, Rn, CO2, and CC. The parameter combinations after Spearman + RandomForest feature selection include 5 feature parameters: Tmax, Ts, CC, Tmin, CO2, and 3 feature parameters: Tmax, Ts, and CC.

This data set divides the training set and the test set according to the ratio of 8:2, and the results below are the model results under the test set. For different parameter combinations as model inputs, RandomForest, LightGBM, and CatBoost models were constructed separately for predicting the water requirements of greenhouse tomato crops. The model results are shown in Fig. 4. Figure 4(a) shows the model prediction results for the 11 feature parameters without feature selection. The RandomForest model has the smallest error and the highest R2. The MSE of the RandomForest model is 0.025 to 0.042 lower than the other two models, the MAE is 0.076 to 0.093 lower, and the RMSE is 0.057 to 0.088 lower. Figure 4(b) shows the model prediction results for the 7 feature parameters after Spearman feature selection. The RandomForest model has the smallest error and the highest R2, with the MSE being 0.059 to 0.068 lower than the other two models, the MAE being 0.12 to 0.145 lower, and the RMSE being 0.126 to 0.14 lower. Figure 4(c) shows the model prediction results for the 5 feature parameters after Spearman + RandomForest feature selection. The RandomForest model has the smallest error and the highest R2, with the MSE being 0.012 to 0.042 lower than the other two models, the MAE being 0.006 to 0.088 lower, and the RMSE being 0.028 to 0.086 lower. Figure 4(d) shows the model prediction results for the 3 feature parameters after Spearman + RandomForest feature selection. The RandomForest model has the smallest error and the highest R2, with the MSE being 0.031 to 0.05 lower than the other two models, the MAE being 0.069 to 0.116 lower, and the RMSE being 0.074 to 0.109 lower. In summary, for the four different parameter combinations, the RandomForest model has the lowest MSE, MAE, and RMSE among the three models, and the highest R2 Among the same RandomForest models, the model with the 5 feature parameter combination after Spearman + RandomForest feature selection has the largest error, and the model with the parameter combination after Spearman feature selection has the smallest error, with the MSE, MAE, and RMSE errors being reduced by 21%, 23%, and 12% respectively, and the R2 being increased by 0.6–2.7%.

Based on the three models (i.e., RandomForest, LightGBM, CatBoost), fusion models (i.e., Average fusion, Weighted fusion, Stacking) were constructed separately for predicting the water requirements of greenhouse tomato crops, and the model results are shown in Fig. 5. Figure 5(a) shows the model prediction results for all 11 feature parameters without feature selection. The errors of the three fusion models are all lower than the best-performing RandomForest model among the single machine learning models, and the R2 is higher. Among them, the Stacking model has the smallest error and the highest R2. The MSE of the Stacking model is 0.012 to 0.013 lower than the other two models, the MAE is 0.011 to 0.015 lower, and the RMSE is 0.034 to 0.038 lower. Figure 5(b) shows the model prediction results for the 7 feature parameters after Spearman feature selection. The MSE of the Stacking model is 0.012 to 0.014 lower than the other two models, and the RMSE is 0.035 to 0.04 lower, with the R2 being 0.037 to 0.043 higher than the other two models. Although the MAE of the Stacking model is higher than the Weighted fusion model, the difference is only 0.001. Figure 5(c) shows the model prediction results for the 5 feature parameters after Spearman + RandomForest feature selection. The MSE of the Stacking model is 0.014 to 0.015 lower than the other two models, the MAE is 0.007 to 0.011 lower, the RMSE is 0.04 to 0.042 lower, and the R2 is 0.042 to 0.044 higher than the other two models. Figure 5(d) shows the model prediction results for the 3 feature parameters after Spearman + RandomForest feature selection. The MSE of the Stacking model is 0.019 to 0.02 lower than the other two models, the MAE is 0.031 to 0.032 lower, the RMSE is 0.054 to 0.056 lower, and the R2 is 0.057 to 0.06 higher than the other two models. In summary, for the four different parameter combinations, the Stacking model has the lowest MSE, MAE, and RMSE among the three fusion models, and the highest R2.

Comparing the best fusion model with the single machine learning model results, as shown in Fig. 6, the Stacking model, which performs the best among the fusion models, has lower error and higher R2 than the RandomForest model, which performs the best among the single machine learning models. Specifically, the MSE is reduced by 0.01, the MAE is reduced by 0.003, the RMSE is reduced by 0.03, and the R2 is increased by 0.03. When using the Stacking model, the model with the 3 feature parameter combination selected by Spearman + RandomForest feature selection has the smallest error, while the model with the parameter combination selected by Spearman feature selection has the largest error. The MSE, MAE, and RMSE errors are reduced by 19%, 16%, and 10% respectively, and the R2 is increased by 1.5%. Therefore, only the three parameters Tmax, Ts, and CC, combined with the proposed Stacking fusion model, can accurately predict the water requirements of greenhouse tomatoes, significantly reducing the computational complexity of traditional formulas.

Model reliability and generalization verification

The performance of the proposed optimal parameter combinations and models is verified in the hourly data of spring-season tomatoes to ensure the reliability of the method at different resolutions. The results of the RandomForest, LightGBM, and CatBoost models are shown in Fig. 7, with Fig. 7(a) displaying the model prediction results for all 11 feature parameters, and Fig. 7(b) showing the model prediction results for the optimal feature parameter combinations. The results of the Average fusion, Weighted fusion, and Stacking models are shown in Fig. 8, with Fig. 8(a) displaying the model prediction results for all 11 feature parameters, and Fig. 8(b) showing the model prediction results for the optimal feature parameter combinations. It can be seen that, whether for the RandomForest, LightGBM, CatBoost models, or for the Average fusion, Weighted fusion, Stacking ensemble models, the prediction error using the optimal feature parameter combinations is lower than that using all feature parameters. Compared to the results using the original full set of parameters within the same model, the MSE is reduced by 0.001 to 0.007, the MAE is reduced by 0.001 to 0.025, and the RMSE is reduced by 0.003 to 0.022. The proposed greenhouse tomato water requirement prediction model, that is, the Stacking ensemble model with feature parameters Tmax, Ts, and CC, performs the best. Compared to the three machine learning models with the original full set of parameters, the MSE is reduced by 26–33%, the MAE is reduced by 5–21%, and the RMSE is reduced by 13–16%.

Figure 9 is a scatter plot of prediction results from all 11 feature parameters in different models using hourly data of spring-season tomatoes, while Fig. 10 is a scatter plot of prediction results from the optimal feature parameter combinations in different models using the same data. It can be observed that, whether for the RandomForest, LightGBM, CatBoost models, or for the Average fusion, Weighted fusion, Stacking ensemble models, the R2 values obtained using the optimal feature parameter combinations are all higher than those using all feature parameters, by 1 to 10% points. The facility tomato water requirement prediction model proposed in this paper, which is the Stacking ensemble model with feature parameters Tmax, Ts, and CC, has the highest R2, with prediction values closer to the actual values. Compared to the three machine learning models with all original parameters, the R2 has increased by 9 to 13% points.

In the autumn-season tomato daily data, the performance of the proposed optimal parameter combinations and models is verified to ensure the generalization of the method. The prediction results of different models for the autumn-season tomato daily data are compared with the true values, as shown in Fig. 11. Figure 11(a) presents the model predict outcomes for all 11 feature parameters, and Fig. 11(b) presents the model predict outcomes for the optimal feature parameter combinations. The horizontal coordinate in the figure represents 12 randomly selected test data, and the vertical axis indicates the mean of the predict outcomes across various models. “Single machine learning model” indicates the mean of the predict outcomes of RandomForest, LightGBM, and CatBoost, “Fusion model” indicates the mean of the predict outcomes of Average fusion, Weighted fusion, and Stacking, and “True value” represents the actual value of the crop water requirement. It can be seen that the predict outcomes of the Fusion model are generally closer to the actual values, and the models using the optimal feature parameter combinations are closer to the true values compared to the models using all 11 feature parameters. Therefore, the proposed fusion model performs better than the single machine learning models, and the models using the optimal feature parameter combinations have better prediction effects.

The results of the RandomForest, LightGBM, and CatBoost models are shown in Fig. 12, with Fig. 12(a) displaying the model prediction results for all 11 feature parameters, and Fig. 12(b) showing the model prediction results for the optimal feature parameter combinations. It can be seen that for the RandomForest, LightGBM, and CatBoost models, the prediction errors using the optimal feature parameter combinations are lower than those using all feature parameters, with MSE reduced by 0.12 to 0.153, MAE reduced by 0.103 to 0.156, RMSE reduced by 0.116 to 0.155, and the predicted R2using the optimal feature parameter combinations is higher than that using all feature parameters, with R2 increased by 0.085 to 0.103. The results for the Average fusion, Weighted fusion, and Stacking models with all 11 feature parameters and the optimal feature parameter combinations are shown in Fig. 13. It can be seen that for the Average fusion, Weighted fusion, and Stacking models, the prediction errors using the optimal feature parameter combinations are lower than those using all feature parameters, with MSE reduced by 0.122 to 0.278, MAE reduced by 0.006 to 0.178, RMSE reduced by 0.162 to 0.181, and the predicted R2 using the optimal feature parameter combinations is higher than that using all feature parameters, with R2 increased by 0.096 to 0.103. In summary, the facility tomato water requirement prediction model proposed in this paper, which is the Stacking ensemble model with feature parameters Tmax, Ts, and CC, performs the best. Compared to the three machine learning models with all original parameters, the MSE is reduced by more than 71%, the MAE is reduced by more than 6%, the RMSE is reduced by more than 41%, and the R2 is increased by more than 13%.

Discussion

The performance of the integrated model in this study is better than that of the single model, which is consistent with the relevant research conclusions21,22. Integration model integrates multiple models with different characteristics and can mine data information from different angles. There are differences in the ability of different models to capture data features, as in image recognition tasks, some models are good at recognizing the contours of objects, while others are sensitive to color features. By integrating these models, data features can be obtained comprehensively, and the generalization ability and prediction accuracy of the model can be effectively improved.

This study found that models with fewer parameters performed better under certain conditions23. Models with many parameters tend to overfit, learn too much noise and details in training data, and have poor generalization ability on new data. However, the model with fewer parameters has a simple structure, can focus on core features and avoid overfitting. In this study, although the parameters of the optimized model are reduced, each characteristic parameter involved in modeling has an important impact on crop water demand, so the prediction is more stable and accurate.

From the perspective of crop physiology and meteorology, temperature parameters (Tmax, Tmin, Ts), relative humidity parameters (RHm) and radiation parameters (Rn) had significant effects on tomato water demand. Alshami et al.24 proposed that solar radiation has a significant impact on the photosynthesis and transpiration of tomatoes. High temperature accelerated transpiration of tomato and increased water demand. Low temperature decreased transpiration but affected root water absorption, so reasonable water supply was needed. Tuzel et al.25 proposed that, in addition to temperature, relative humidity and radiation also have a significant impact on the transpiration and water requirements of tomatoes. Low relative humidity caused rapid water evaporation and increased water demand, high relative humidity inhibited transpiration and reduced water demand, but disease control should be taken into account. Radiation promoted tomato photosynthesis, increased water demand for time cooperation, and heated up leaves to accelerate water evaporation. However, excessive radiation damaged leaves and changed water demand, so irrigation strategies should be adjusted according to its changes.

However, there are still some limitations in this study. For example, the image segmentation algorithm is greatly affected by natural conditions such as illumination change and occlusion; The data based on the model construction is not long enough in time span, only covering spring and autumn tomatoes, and it is difficult to reflect the influence of climate fluctuation and planting mode adjustment on tomato water demand in different years. In practical application scenarios, the impact of factors such as ventilation equipment operation and irrigation system differences on the tomato canopy microenvironment is not fully considered, which limits the adaptability of the prediction model under different facility conditions and makes it difficult to directly apply it to the cultivation environment of various facilities to accurately predict the tomato water requirement. In the future, we can improve the water demand prediction method of tomato by optimizing algorithm model, expanding data range and considering environmental factors comprehensively.

Conclusion

Accurate prediction of crop water requirements can serve as a basis for irrigation decision-making and contribute to the stable growth of crops. The paper proposes an image segmentation-based algorithm for extracting the canopy coverage of greenhouse tomatoes, which was applied to both spring and autumn crops to extract the canopy coverage. By combining Spearman’s correlation analysis and the random forest feature importance ranking method, an optimal combination of feature variables was proposed. Ultimately, a water requirement prediction model for greenhouse tomato crops was constructed using single machine learning algorithms and ensemble algorithms. Using daily data from the spring season for parameter selection and model building, it was found that models with different combinations of parameters, particularly Tmax, Ts, and CC, had the greatest impact on the water requirements of greenhouse tomatoes, and the Stacking ensemble model showed the best prediction performance. Compared to single machine learning models, the MSE, MAE, and RMSE errors were reduced by more than 31%, 12%, and 17% respectively, and the R2 was increased by more than 3%. Compared to the Stacking model without feature selection, the MSE, MAE, and RMSE errors were reduced by 19%, 16%, and 10% respectively, and the R2 was improved by 1.5%. Moreover, good results were achieved in both hourly data from the spring season and daily data from the autumn season. Compared to the original RandomForest, LightGBM, and CatBoost models with all parameters, the MSE was reduced by more than 26%, the MAE was reduced by more than 5%, the RMSE was reduced by more than 13%, and the R2 was increased by more than 9%. Therefore, the multi-source data fusion model for predicting the water requirements of greenhouse tomato crops proposed in this paper has excellent reliability and generalization. Compared to the traditional PM model, this model uses image algorithms to extract key crop growth parameters, saving manpower. It also reduces the model’s required parameters and computational complexity, and can effectively predict crop cultivation water requirements.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Peter, A. Y. A., Eric, O. & Ernesto, O. G. Indoor vegetable production: an alternative approach to increasing cultivation. Plants 11 (21), 2843. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11212843 (2022).

Gao, H. et al. Protected cultivation can mitigate carbon emissions for tomato production. Agric. Commun. 2 (4), 100065. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrcom.2024.100065 (2024).

Babakos, K. et al. Assessing the robustness of pan evaporation models for estimating reference crop evapotranspiration during recalibration at local conditions. Hydrology 7 (3), 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology7030062 (2020).

Yan, H. et al. Parametrization of aerodynamic and canopy resistances for modeling evapotranspiration of greenhouse cucumber. Agric. For. Meteorol. 262, 370–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2018.07.020 (2018).

Ge, J. et al. Prediction of greenhouse tomato crop evapotranspiration using XGBoost machine learning model. Plants 11 (15), 1923. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11151923 (2022).

Ge, J. K., Liu, Y. F., Liu, Z. J., Gong, X. W. & Xu, C. D. Comparing the performance of greenhouse crop transpiration prediction models based on ANNs. J. Environ. Biol. 40 (3), 418–426. https://doi.org/10.22438/jeb/40/3(SI)/Sp-02 (2019).

Cahn, M. D., Johnson, L. F. & Benzen, S. D. Evapotranspiration based irrigation trials examine water requirement, nitrogen use, and yield of Romaine lettuce in the Salinas Valley. Horticulturae 8 (10), 857. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae8100857 (2022).

Jo, W. J. & Shin, J. H. Development of a transpiration model for precise tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) irrigation control under various environmental conditions in greenhouse. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 162, 388–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2021.03.005 (2021).

Dong, J. et al. Estimating reference crop evapotranspiration using optimized empirical methods with a novel improved grey Wolf algorithm in four Climatic regions of China. Agric. Water Manage. 291, 108620. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2023.108620 (2024).

Ghumman, A. R. et al. Simulation of pan-evaporation using Penman and Hamon equations and artificial intelligence techniques. Water 13 (6), 793. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13060793 (2021).

Dong, J. et al. Estimating crop evapotranspiration of wheat-maize rotation system using hybrid convolutional bidirectional long Short-Term memory network with grey Wolf algorithm in Chinese loess plateau region. Agric. Water Manage. 301, 108924. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2024.108924 (2024).

Fuentes, S., Ortega-Farías, S., Carrasco-Benavides, M., Tongson, E. & Viejo, C. G. Actual evapotranspiration and energy balance Estimation from vineyards using micro-meteorological data and machine learning modeling. Agric. Water Manage. 297, 108834. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2024.108834 (2024).

Tunalı, U., Tüzel, I., Tüzel, Y. & Şenol, Y. Estimation of actual crop evapotranspiration using artificial neural networks in tomato grown in closed soilless culture system. Agric. Water Manage. 284, 108331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2023.108331 (2023).

Javier, H. P., Gonzalo, P. & María, G. A segmentation method using Otsu and fuzzy k-Means for stereovision matching in hemispherical images from forest environments. Appl. Soft Comput. J. 11 (8), 4738–4747. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2011.07.010 (2011).

Lu, Y. Z., Gong, M. L., Li, J. & Ma, J. S. Investigating the effects of full-spectrum LED lighting on strawberry traits using correlation analysis and time-series prediction. Plants-Base 13(2), 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants13020149 (2024).

Speiser, J. L., Miller, M. E., Tooze, J. & Ip, E. A comparison of random forest variable selection methods for classification prediction modeling. Expert Syst. Appl. 134, 93–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2019.05.028 (2019).

Jing, W., Qian, B. & Li, Y. N. Study on food safety risk based on LightGBM model: a review. Food Sci. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1590/fst.42021 (2022).

Hancock, J. T. & Khoshgoftaar, T. M. CatBoost for big data: an interdisciplinary review. J. Big Data. 7 (1), 94. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-54646/v1 (2020).

Zhang, Y., Xiong, A., Xiao, Y. & Chen, Z. Y. A new combination method based on pearson coefficient and information entropy for multi-sensor data fusion. Inf. Softw. Technol. 161, 107248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infsof.2023.107248 (2023).

Xie, B. et al. Rapid identification of Choy sum seeds infected with penicillium decumbens based on hyperspectral imaging and stacking ensemble learning. Food. Anal. Methods. 17(3), 416–425. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12161-024-02574-0 (2024).

Su, Z. B., Luo, J. Q., Wang, Y., Kong, Q. M. & Dai, B. S. Comparative study of ensemble models of deep convolutional neural networks for crop pests classification. Multimedia Tools Appl. 82(19), 29567–29586. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-023-14884-2 (2023).

Rajput, J. et al. Assessment of data intelligence algorithms in modeling daily reference evapotranspiration under input data limitation scenarios in semi-arid Climatic condition. Water Sci. Technol. 87(10), 2504–2528. https://doi.org/10.2166/wst.2023.137 (2023).

Yu, F. et al. Integration of a parameter combination discriminator improves the accuracy of chlorophyll inversion from spectral imaging of rice. Agric. Commun. 2(3), 100055. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrcom.2024.100055 (2024).

Alshami, A. K. et al. Responses of tomato crop and water productivity to deficit irrigation strategies and salinity stress in greenhouse. Agric. Water Manage. 270, 107844. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2023.107845 (2023).

Tüzel, Y. et al. Deficit irrigation response and climate resilience of mediterranean tomato landraces. Horticulturae 11(1), 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11010074 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Youth Research Fund of Beijing Academy of Agriculture and Forestry Sciences (grant number: QNJJ202408), Major discipline cultivation project of Beijing Academy of Agriculture and Forestry Sciences, Beijing Capital Agribusiness & Foods Group independent science and technology project(grant number: SNSPKJ(2022)01), Beijing Nova Program(grant number: 20230484375).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xinyue Lv: Writing – original draft. Lili Zhangzhong: Conceptualization, Methodology. Chaoyang Tong: Data processing. Yibo Wei and Guangwei Li: Visualization. Youli Li and Yingru Yang: Investigation, Formal analysis. Lili Zhangzhong: Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lv, X., Li, Y., Zhangzhong, L. et al. Maximizing multi-source data integration and minimizing the parameters for greenhouse tomato crop water requirement prediction. Sci Rep 15, 29161 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12324-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12324-9