Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly disrupted influenza forecasting, making it challenging for hospitals to anticipate the severity of upcoming flu seasons relative to typical annual respiratory virus patterns. Even for influenza, health facilities often lack precise information on potential influenza surges, which hinders hospital management’s ability to anticipate necessary changes with respect to hospital staffing and resource allocation for an influx of patients. This study addresses this critical gap by developing an enhanced predictive model for pediatric influenza hospitalizations in Massachusetts. By integrating data from the Health and Human Services (HHS) Protect Public Data Hub, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) FluSurv-NET, U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) mobility data, and regional hospitalization rates, we demonstrate how recent improvements in data analytics and population tracking can amplify disease forecasts, and more precisely anticipate hospital burden relative to historical patient intake and hospital utilization trends.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Influenza remains a persistent public health threat, especially for pediatric populations who are more vulnerable to severe illness and who often play a key role in virus transmission dynamics. Accurate and timely forecasting of pediatric influenza is essential for healthcare systems to allocate resources, guide preventative measures, and manage hospital capacity during peak respiratory virus seasons1. However, most existing surveillance and modeling efforts focus on population-wide trends and often lack the specificity needed to inform pediatric care, leaving hospitals without adequate foresight into potential surges in child admissions.

The COVID-19 pandemic further exposed structural weaknesses in public health surveillance systems, particularly in pediatric data coverage. Efforts such as the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Protect Public Data Hub enhanced situational awareness by providing hospital-level information on respiratory illness burden and bed capacity. These initiatives demonstrated the potential benefits of integrating real-time, operational data into infectious disease surveillance systems2. Despite these improvements, pediatric influenza forecasting remains hindered by limited spatial resolution, inconsistent off-season data collection, and a lack of tailored models for child health planning.

Traditional surveillance systems, including the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) FluSurv-NET, the European Influenza Surveillance Network (EISN), and the World Health Organization’s Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System (GISRS), rely primarily on syndromic surveillance to monitor disease incidence and trends3,4,5. These systems leverage real-time clinical data to detect outbreaks based on symptom presentation rather than confirmed diagnoses. However, they typically lack age-stratified specificity, limiting their usefulness for pediatric surge forecasting and operational planning.

This study addresses these limitations by developing a pediatric-specific forecasting model that estimates biweekly influenza-related hospitalizations in Massachusetts. We integrate multiple data streams, CDC FluSurv-NET, HHS Protect, U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) mobility data, and regional hospitalization estimates, to construct a predictive framework that reflects both clinical and behavioral drivers of pediatric influenza transmission. The model leverages the Facebook Prophet time series platform to accommodate seasonal patterns and incorporate exogenous variables that influence influenza dynamics, such as mobility and regional trends.

By focusing on pediatric populations and operationally relevant timeframes, this research aims to bridge the gap between theoretical epidemiological modeling and healthcare decision-making—an essential component for improving emergency preparedness and patient outcomes6. The approach aims to provide localized, data-driven forecasts to improve emergency preparedness and hospital response during respiratory virus seasons marked by high uncertainty and potential compounding threats.

Background—forecasting of pediatric influenza incidence and hospital burden

Influenza surveillance has evolved over the past century from reactive monitoring to proactive modeling efforts that incorporate both epidemiological and behavioral indicators. Early 20th-century surveillance efforts were limited by inconsistent data collection and lacked the capacity to forecast disease spread7,8. By the mid-20th century, systems like the CDC’s Influenza Surveillance System formalized data collection, allowing for improved detection and response to seasonal outbreaks9.

Initial forecasting models employed statistical methods, such as linear regression, to identify temporal trends in influenza incidence10. With advances in computational power and data availability, more sophisticated models emerged. Mechanistic models, including SEIR and Bayesian hierarchical frameworks, began to incorporate disease transmission pathways, parameter uncertainty, and geographic variation11,12. More recently, real-time forecasting approaches have integrated machine learning techniques such as Random Forests, Support Vector Machines, and Neural Networks to handle complex, nonlinear relationships in transmission dynamics and hospitalization burden13.

A critical advancement has been the incorporation of exogenous variables, including mobility data, weather trends, and healthcare system strain, into forecasting models14,15. For example, French models using school holiday data have demonstrated significant reductions in influenza attack rates, showing a 25% decrease from 45 to 20% when school closures were incorporated into simulation scenarios16. Similarly, geospatial and mobility data have been shown to improve influenza forecasts by capturing behavioral influences on transmission, particularly during high-travel or high-density periods17.

Pediatric populations present unique forecasting challenges. Children not only face greater clinical vulnerability to influenza-related complications18,19, but pediatric hospitalizations also place disproportionate strain on healthcare systems due to limited bed availability, specialized medical equipment, and tailored pharmaceutical needs20,21. Pediatric healthcare infrastructure often lacks redundancy, and localized surges in respiratory illness can rapidly exhaust available resources22,23.

Despite these concerns, U.S. surveillance systems such as CDC FluSurv-NET do not consistently collect pediatric-specific data with adequate spatial and temporal resolution5,24,25. Moreover, facility-level tracking is inconsistent, and hospitalization counts are often underreported or aggregated at levels that obscure operationally relevant trends26. These gaps are particularly evident during off-season months or years when influenza activity is suppressed, as occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic2,27. During the 2020–2021 season, for example, FluSurv data were not collected, and HHS Protect exhibited extensive missing data, undermining continuity in pediatric influenza monitoring.

The pandemic also destabilized traditional surveillance and transmission dynamics. Public health responses such as masking, school closures, and travel restrictions suppressed influenza circulation and challenged model calibration efforts. However, these disruptions also demonstrated the value of real-time data platforms and behavioral indicators, such as mobility and regional transmission estimates, for forecasting hospital burden28.

Addressing these challenges requires models capable of integrating exogenous variables and resolving pediatric trends at a temporal and spatial resolution relevant for hospital preparedness. Surveillance systems must evolve to support age-stratified, real-time forecasting for respiratory viruses, particularly as cocirculating pathogens like RSV and SARS-CoV-2 increasingly converge with seasonal influenza29,30. Enhanced modeling frameworks that support anticipatory health system operations and resource allocation are essential for resilient public health infrastructure.

Methods

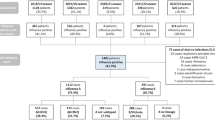

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted established patterns in respiratory virus transmission, surveillance, and forecasting leading to gaps and uncertainty in data essential for predicting and managing influenza surges31. At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, surveillance efforts focused on leveraging existing CDC datasets and online surveillance methods to fill the emerging data gaps. However, as the pandemic progressed, it became evident that a more integrated approach was required. This prompted a strategic shift towards the newly established HHS Protect public data hub, which provided daily to weekly access to health facility COVID-19 and influenza data, including bed capacity and weekly hospitalization counts32. Despite these advancements, gaps persisted within both HHS Protect and CDC FluSurv, particularly during off-season periods and the 2020–2021 influenza season. Specifically, CDC FluSurv did not collect data outside the typical influenza season and was absent for the 2020–2021 season, while HHS Protect showed significant data gaps, particularly prior to 2021 and between 2021 and 20225,32. The missing data from both CDC FluSurv and HHS Protect are illustrated in Figs. 1 and 2 below. These figures highlight the disparity in comprehensive data collection, with CDC FluSurv displaying hospitalization rates and HHS Protect showing hospitalization counts. The pink dots represent gaps in the data set.

These limitations in surveillance coverage and continuity underscores the need for a more resilient and adaptive modeling strategy. In response, a robust methodological framework was developed to create a forecasting model for influenza among pediatric populations in Massachusetts. The modeling approach is outlined in Fig. 3.

Data collection

We began by collecting publicly available data from multiple sources. These include: Health and Human Services (HHS) Protect Public Data Hub, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) FluSurv-NET, U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) mobility data, and pediatric hospitalization rates from surrounding states (New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware). These datasets were integrated to create a comprehensive dataset, providing the foundation for the forecasting model.

CDC FluSurv-Net

The CDC FluSurv-NET provides weekly data on influenza hospitalization rates, stratified by age groups. While this dataset primarily focuses on laboratory-confirmed influenza cases, its age-specific hospitalization rates are critical for this study. However, the coverage of FluSurv is limited as it only includes data from 10 U.S. states, representing approximately 9% of the U.S. population5. This limitation means that the data does not fully capture the national picture of influenza hospitalizations. Additionally, FluSurv does not include information on out-of-season influenza hospitalization rates, which can be a significant gap for comprehensive epidemiological studies.

HHS protect

HHS Protect provides extensive facility-level data regarding hospital capacity and the impact of COVID-19, accessible through their portal32. Developed in 2019, it was made to act as the COVID-19 central data repository, aggregating United States healthcare data from various HHS operating divisions. This dataset includes detailed metrics such as bed occupancy, the number of COVID-19 infections, and influenza patient hospitalization counts. HHS Protect data has been crucial for various research areas, including studies on COVID-19’s strain on healthcare systems and patient outcomes. It has also been pivotal in research on COVID-19 and influenza co-infections, exemplified by studies such as the one published in33. Additionally, the dataset supports research focused on hospital capacity and COVID-19 age-specific impacts.

Estimating pediatric influenza hospitalization counts

Utilizing these two datasets we derive the pediatric hospitalization estimate detailed below:

1)

2)

3)

4)

(See Appendix for detailed variable data tables).

DOT mobility data

To enhance the model’s predictions, DOT mobility data was incorporated34. This data source includes daily updates with columns for both monthly and weekly analysis, offering a granular view of population movements. Utilizing mobile data weighted to represent millions of devices, it ensures a comprehensive and representative sample at the national, state, and county levels. One key metric tracked by the DOT is the “population not staying at home,” which measures the number of residents who have moved at least a mile from their home, capturing behavioral indicators that influence influenza transmission dynamics.

Neighboring state hospitalization rates

Hospitalization data, HHS protect, from New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware were included to model regional disease trends. These were selected based on literature that influenza spread may follow south–to–north patter, consistence with seasonal mobility and climate patterns. We harmonized these data to match Massachusetts’ derived estimates and aligned them by week.

Data preprocessing

Data preprocessing involved several steps to ensure quality and completeness. Missing values in the HHS Protect data, particularly for low influenza hospitalization counts (1–4), were addressed using median imputation. Forward fill techniques were employed to estimate unreported data points, ensuring temporal continuity. Specifically, the “last value carried forward” fill technique was applied to carry the last known observation forward to fill in gaps caused by missing data at random35. For example, if a value was missing in a particular week, the value from the previous week was used as an estimate. While forward fill can introduce bias if the gap spans a long period, potentially deviating from the actual trend, the method never exceeds more than 2 weeks’ time while in flu season. The CDC FluSurv-NET dataset, which lacks coverage for weeks 18–39 outside the typical influenza season, was addressed using zero imputation for these weeks, assuming minimal flu activity. The datasets were then merged based on temporal (week and year) and spatial (state) identifiers.

Forecasting model

The forecasting model was developed using Facebook Prophet, a flexible time series forecasting tool known for its ability to handle various temporal trends and seasonality36. The simple, open-source platform gained popularity among researchers during the COVID-19 pandemic37. Prophet was notably used in COVID-19 modeling efforts, where studies highlighted its advantages in forecasting COVID-19 cases by decomposing data components and capturing temporal characteristics, even when data changes significantly38. Prophet models the underlying trend in the data using a piecewise constant growth rate, accommodating abrupt changes and non-linear trends, which are essential for capturing the dynamic nature of disease transmission and health outcomes, such as influenza hospitalizations. The model uses Fourier series with orders chosen based on cross-validation to balance complexity and overfitting risks, and it includes multiple seasonal components: weekly, monthly, and yearly. School breaks and public holidays were incorporated as special events, allowing the model to account for short-term deviations in hospitalization rates.

Incorporating exogenous variables

Exogenous variables, including DOT mobility data and pediatric hospitalization rates from surrounding states, were integrated into the model to provide additional context on behavioral and regional factors influencing influenza transmission. DOT mobility data, for instance, offers a proxy for human movement patterns which are known to impact the spread of respiratory viruses like influenza. This was highlighted during COVID-19 where travel restrictions, city lockdowns, and restrictions on mass gathering were proven effective in controlling the spread of COVID-19 a similarly spread virus39. Moreover, hospitalization rates from surrounding states serve as indicators for regional disease burden and healthy system strain, factors directly influencing transmission dynamics. This can be seen as a University of Chicago research team was able to model the social connectivity of populations to predict typical outbreak trends28. The number of close friends, family, and communities who all visit and know each other have much higher opportunities to spread the flu. Together these variables enhance the model’s predictive power by capturing the complex interplay between influenza transmission and population behaviors.

Training and validation

The model was trained on historical data from 2019 to February of 2024, with separate subsets used for training and validation. Data splitting involved a strategic approach to ensure both subsets would provide a balanced and comprehensive representation of the entire dataset, particularly in the context of analyzing the effects of COVID-19 from 2019 to 2024. The dataset was split by selecting every other data point, a method designed to preserve temporal integrity and maintain a consistent distribution of key trends across both training and testing datasets.

This approach, while unconventional, was chosen to ensure that both subsets encompassed data from all years, including critical periods before, during, and after the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic. By alternating data points, the model was exposed to a wide range of temporal patterns and seasonal effects in both the training and testing phases, thus allowing for a more robust evaluation of the model’s performance across different periods. This method prevents the training dataset from being overly focused on specific years or seasons, which could lead to a biased model that doesn’t generalize well to unseen data.

Prophet employs Stan’s L-BFGS optimization algorithm to estimate model parameters, iteratively updating them to maximize the likelihood and ensure the best fit to historical data. Cross-validation was performed providing robust performance metrics, including Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and coverage (the proportion of observed values within the prediction interval). RMSE measures the standard deviation of prediction errors, providing insights into the typical deviation of predictions from observed values. MAE indicates the average absolute difference between predicted and observed values, reflecting overall accuracy. Coverage assesses the reliability of prediction intervals by measuring the proportion of observed values within these intervals.

A summary of the data sources and how they are used in the model is highlighted in Table 1:

Results

The baseline model, which relied solely on primary influenza hospitalization data produced a two week root mean squared error (RMSE) of 60.38 hospitalizations, a mean absolute error (MAE) of 46.70 hospitalizations and a coverage of 37%, indicating prediction uncertainty and a potential underestimation of hospital variation. These metrics are detailed in Table 2. To contextualize this error range, in-season pediatric hospitalizations during the study period ranged from approximately 100 to 250 cases, highlighting the operational impact of the model’s forecast deviations. The one-week forecasts had a slightly better performance, with an RMSE of 57.55 and MAE of 44.62. However, prediction intervals frequently failed to capture observed values during early-season lows, sometimes producing negative values requiring zero-imputation.

This adjustment was ensured that the forecasted values remained within a plausible range, reflecting the actual behavior of the data. Following the imputation, error metrics were recalculated to avoid skewing the results with these unrealistic predictions. Despite the seasonal fine-tuning efforts, the recalculated errors improved the model’s performance assessment, better aligning predictions with realistic influenza expectations and minimizing the impact of periods with low influenza activity.

Further adjustments, such as introducing a lower bound (cap) or re-evaluating the seasonal components, may be necessary to enhance the model’s robustness and accuracy. Additionally, it may be beneficial to explore alternative modeling approaches that can better handle such extreme variations, particularly in datasets with sparse or low-frequency events.

Figure 4 illustrates the observed versus predicted hospitalization trends for the baseline model.

To enhance the prediction of operationally relevant pediatric hospitalizations, we incorporated several indicators to provide the model with more contextual information on virus spread, thereby improving short-term hospitalization forecasts. In Table 3, we conducted a sensitivity analysis comparing each individual variable and their combinations against the baseline model.

The enhanced model’s time series plot, shown in Fig. 5, reveals a much closer alignment between predicted and observed trends, especially during peak seasons of illness. The prediction bounds were narrower, reflecting increased confidence in the forecasts, and the model successfully captured sudden changes in hospitalization rates that the baseline model missed.

In comparing the baseline and enhanced models, the performance improvements of the were consistent across all forecasting windows. Table 5 provides a side-by-side comparison of key performance metrics for both models, highlighting the improvements achieved by incorporating external variables.

Incorporating DOT mobility data and hospitalization counts from neighboring states significantly improved model predictions, with the enhanced model demonstrating notable gains in predictive accuracy. Specifically, in a significant reduction in RMSE values dropped to 51.07 hospitalizations at 2 weeks (a 15% improvement). The MAE values for the enhanced model also decreased markedly to 32.40 hospitalizations at 2 weeks (a 31% improvement). The coverage metric improved significantly, with the highest coverage observed at 52% for the two-week forecast window (a 41% improvement). As a result, forecasts better tracked seasonal peaks and short-term fluctuations in hospitalizations.

Discussion

This study addresses a significant gap in operational forecasting for pediatric influenza hospitalizations, demonstrating how contextual variables, particularly DOT mobility data and regional hospitalization rates, can substantially improve model accuracy. These gains are especially meaningful for pediatric care settings, where small forecasting errors can translate into critical resource mismatches during high-demand periods40. The enhanced model’s MAE of 32.40 hospitalizations, compared to the baseline’s 46.70, represents a 13–32% deviation during seasonal peaks of 100–250 weekly cases. In operational terms, this improvement can assist administrators in better planning for staff deployment, surge capacity, and medical supply availability. Improved coverage also reflects a more accurate representation of uncertainty, which is essential in real-world decision-making under dynamic and resource-constrained conditions13.

Crucially, the integration of exogenous data into the Prophet framework provides a flexible and interpretable way to account for behavioral and regional dynamics in influenza spread. DOT mobility metrics serve as a proxy for interpersonal contact and movement patterns, which strongly influence disease transmission, particularly during holidays or school breaks15,41. Regional hospitalization data offers early warning signals for incoming surges, providing an operational advantage to facilities downstream of known transmission corridors14.

The modeling approach also underscores the growing utility of publicly available, high-resolution datasets in applied public health forecasting. These data streams, while imperfect, offer sufficient signal to support practical interventions when structured, cleaned, and integrated appropriately42. Although the study relied on data imputation to address missing values, especially for the HHS Protect dataset and off-season gaps in FluSurv-NET, such preprocessing did not compromise the model’s operational value. Nonetheless, future work could improve these processes through more sophisticated imputation techniques or probabilistic gap-filling strategies35.

Finally, while short-term (one-week) forecasts are often more precise, our focus on a two-week prediction window aligns more directly with real-world decision timelines for surge planning, staffing coordination, and supply chain readiness. These biweekly forecasts strike a practical balance between prediction accuracy and lead time, and may serve as a prototype for other location-specific or subpopulation-specific influenza models43.

Conclusion

Pediatric influenza forecasting remains a critical need in public health preparedness, especially in the wake of COVID-19 disruptions to seasonal respiratory virus patterns. This study presents a flexible, data-driven forecasting approach that integrates multiple exogenous variables to improve prediction accuracy for pediatric hospital burden in Massachusetts. By incorporating DOT mobility data and hospitalization trends from nearby states, we demonstrate that modest yet strategically chosen variables can meaningfully improve forecasting performance in operational contexts.

The enhanced model’s capacity to reduce error and increase reliability makes it a valuable tool for hospital administrators, particularly those operating within constrained pediatric care networks. These findings support a broader shift toward anticipatory and data-informed healthcare system planning, where real-time forecasting tools can guide short- and medium-term resource allocation.

Looking forward, this approach could be extended to other states or adapted for other respiratory viruses, particularly as cocirculating pathogens like RSV and COVID-19 continue to challenge capacity planning. A modular framework integrating behavioral, spatial, and environmental indicators will be essential for building resilient, responsive public health systems. Continued investment in granular surveillance infrastructure and interdisciplinary forecasting methods will be key to improving health outcomes and maintaining operational readiness in pediatric care environments.

Data availability

All data may be publicly accessed here: https://github.com/bellinport22/Pediatric-Modeling-.

References

Dugast, M., Bouleux, G., Mory, O. & Marcon, E. Improving health care management through persistent homology of time-varying variability of emergency department patient flow. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 23(5), 2174–2181https://doi.org/10.1109/JBHI.2018.2882748 (2019).

Mathis, S. M. et al. Evaluation of flusight influenza forecasting in the 2021-22 and 2022-23 seasons with a new target laboratory-confirmed influenza hospitalizations (2023).

European Influenza Surveillance Network (EISN). Accessed Jun 20, 2025. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/about-us/partnerships-and-networks/disease-and-laboratory-networks/eisn.

Hay, A. J. & McCauley, J. W. The WHO global influenza surveillance and response system (GISRS)—a future perspective, Influenza Other Respir Viruses 12(5), 551–557. https://doi.org/10.1111/irv.12565 (2018).

Influenza Hospitalization Surveillance Network (FluSurv-NET) | CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/weekly/influenza-hospitalization-surveillance.htm (2024).

Bedi, J. S., Vijay, D., Dhaka, P., Singh Gill, J. P. & Barbuddhe, S. B. Emergency preparedness for public health threats, surveillance, modelling & forecasting. Indian J. Med. Res. 153 (3), 287. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_653_21 (2021).

Noymer, A. & Garenne, M. The 1918 influenza epidemic’s effects on sex differentials in mortality in the united States. Popul. Dev. Rev. 26 (3), 565–581 (2000).

Fineberg, H. V. Pandemic preparedness and Response—Lessons from the H1N1 influenza of 2009. N. Engl. J. Med. 370, 1335–1342. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1208802 (2014).

Thacker, S. B. & Berkelman, R. L. Public health surveillance in the united States. Epidemiol. Rev. 10, 164–190. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036021 (1988).

Mills, C. E., Robins, J. M. & Lipsitch, M. Transmissibility of 1918 pandemic influenza. Nature 432, 904–906. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature03063 (2004).

Shaman, J. & Karspeck, A. Forecasting seasonal outbreaks of influenza, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 109(50), 20425–20430. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1208772109 (2012).

’Agostino, D., McGowan, G. L., Murray, E. & K. H., and Quantifying uncertainty in mechanistic models of infectious disease. Am. J. Epidemiol. 190 (7), 1377–1385. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwab013 (2021).

Desai, A. N. et al. Real-time epidemic forecasting: challenges and opportunities. Health Secur 17(4), 268–275. https://doi.org/10.1089/hs.2019.0022 (2019).

Papagiannopoulou, E., Bossa, M. N., Deligiannis, N. & Sahli, H. Long-Term regional Influenza-Like-Illness forecasting using exogenous data. IEEE J. Biomedical Health Inf. 28 (6), 3781–3792. https://doi.org/10.1109/JBHI.2024.3377529 (2024).

Venkatramanan, S. et al. Forecasting influenza activity using machine-learned mobility map. Nat. Commun. 12 (1), 726. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-21018-5 (2021).

Nichol, K. L. et al. Modeling Seasonal Influenza Outbreak in a Closed College Campus: Impact of Pre-Season Vaccination, and PLOS ONE, 5, 3, e9548, doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0009548. (2010).

Ruktanonchai, C. W. et al. Practical Geospatial and sociodemographic predictors of human mobility. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 15389. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-94683-7 (2021).

Nayak, J., Hoy, G. & Gordon, A. Influenza in Children. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Med. 11(1), 038430 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a038430

Nair, H. et al. Global and regional burden of hospital admissions for severe acute lower respiratory infections in young children in 2010: a systematic analysis. Lancet 381(9875), 1380–1390. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61901-1 (2013).

Yoshikawa, H. et al. Effects of the global coronavirus Disease-2019 pandemic on early childhood development: Short- and Long-Term risks and mitigating program and policy actions. J. Pediatr. 223, 188–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.05.020 (2020).

Jones, S. & Walter, M. Shortages of care and medical devices affecting the pediatric patient population. Can. J. Health Technol. 3(8). https://doi.org/10.51731/cjht.2023.719 (2023).

Fay, M., Leipziger, D., Wodon, Q. & Yepes, T. Achieving child-health-related millennium development goals: the role of infrastructure. World Dev. 33(8), 1267–1284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2005.03.001 (2005)

Lavilledieu, D. et al. Implementation of an organizational infrastructure paediatric plan adapted to bronchiolitis epidemics. J. Infect. Public Health. 13 (2), 167–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2019.07.007 (2020).

Getzzg What are the characteristics of participatory surveillance systems for influenza-like-illness? JOGH. https://jogh.org/2023/jogh-13-04130/ (2023).

Perez, A. Respiratory virus surveillance among children with acute respiratory Illnesses—New vaccine surveillance network, United States, 2016–2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 71 https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7140a1 (2022).

Shan, S. et al. Optimizing global influenza surveillance for locations with deficient data (Student Abstract, in Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. https://doi.org/10.1609/aaai.v36i11.21659 (2022).

FluSight, C. D. C. https://www.cdc.gov/flu-forecasting/about/index.html (2024).

Data analysis. shows what drives the spread of flu—UChicago Medicine. XXXX. https://www.uchicagomedicine.org/forefront/biological-sciences-articles/2018/february/massive-data-analysis-shows-what-drives-the-spread-of-flu.

Mahase, E. Winter pressure: RSV, flu, and covid-19 could push NHS to breaking point, report warns. BMJ 374, n1802. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n1802 (2021).

Klein, B. et al. Forecasting hospital-level COVID-19 admissions using real-time mobility data. Commun. Med. 3(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-023-00253-5 (2023).

Medicine, T. L. R. COVID-19 pandemic disturbs respiratory virus dynamics. Lancet Respir. Med. 10(8), 725. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(22)00255-7 (Aug. 2022).

COVID-19. Reported patient impact and hospital capacity by facility | HealthData.gov. https://healthdata.gov/Hospital/COVID-19-Reported-Patient-Impact-and-Hospital-Capa/anag-cw7u/about_data. Accessed: Jun. 20, 2025.

SARS-CoV-2 and influenza coinfection throughout the COVID-19 pandemic: an assessment of coinfection rates, cohort characteristics, and clinical outcomes | PNAS Nexus | Oxford Academic. https://academic.oup.com/pnasnexus/article/1/3/pgac071/6628667?login=false

Trips by Distance. | BTS Data Inventory. https://data.bts.gov/Research-and-Statistics/Trips-by-Distance/w96p-f2qv/about_data.

Bennett, D. A. How can I deal with missing data in my study? Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health. 25 (5), 464–469. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-842X.2001.tb00294.x (2001).

Taylor, S. J. & Letham, B. Forecasting at scale, PeerJ Inc., e3190v2. https://doi.org/10.7287/peerj.preprints.3190v2. (2017).

Lounis, M. Predicting active, death and recovery rates of COVID-19 in Algeria using facebook’ prophet model. 2021. https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202103.0019.v1.

Wang, Y. et al. Prediction and analysis of COVID-19 daily new cases and cumulative cases: times series forecasting and machine learning models. BMC Infect. Dis. 22 (1), 495. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-022-07472-6 (2022).

Ayouni, I. et al. Effective public health measures to mitigate the spread of COVID-19: A systematic review. BMC Public. Health. 21, 1015. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11111-1 (2021).

Cushing, A. M., Bucholz, E. M., Chien, A. T., Rauch, D. A. & Michelson, K. A. Availability of pediatric inpatient services in the united States. Pediatrics 148(1), e2020041723. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-041723 (2021).

Ruktanonchai, C. W. et al. Practical Geospatial and sociodemographic predictors of human mobility. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 15389. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-94683-7 (2021).

Dixon, S. et al. A comparison of infectious disease forecasting methods across locations, diseases, and time. Pathogens 11(2), Art. no. 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens11020185 (2022).

Shaman, J. & Karspeck, A. Forecasting seasonal outbreaks of influenza. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 109(50), 20425–20430. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1208772109 (2012).

Funding

This article is based upon work supported by USACE ERDC’s FLEX-4 Projects on Health System Infrastructure Resilience and Systemic Resilience.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ellinport led idea conceptualization, methodological development, analysis, and draft writing. Wells, Rai, and Rader assisted with methodological development and analysis. Cummings wrote initial draft and revised draft material. Trump assisted with idea conceptualization and writing. Linkov provided project supervision throughout effort.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors report no competing financial or non-financial interests. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the individual authors and not those of the U.S. Army, US government, or other sponsor organizations. This project was supported in part by an appointment to the Center for Health Engineering at the US Army Engineering Research and Development Center administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through an interagency agreement between the U.S. Department of Energy and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ellinport, B., Wells, E., Rai, D. et al. A systems approach for anticipating post-pandemic forecast challenges for pediatric influenza and hospital burden. Sci Rep 16, 493 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12377-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12377-w