Abstract

Multi-band photometric observations of three contact binaries (ATO J255.8159+16.8821, CRTS J034336.4+264312, and NSVS 2669503) were carried out using the 1.88 m telescope at the Kottamia Astronomical Observatory (KAO) in Egypt. New times of minima for all three systems have been calculated. In particular, for NSVS 2669503, we performed an \(O-C\) analysis to investigate period variations. The results indicate a decreasing orbital period, with a rate of \(\textrm{d}P/\textrm{d}t \approx 1.85 \times 10^{-10}\) days yr\(\phantom{0}^{-1}\). Analysis using the Wilson-Devinney (W-D) program revealed that all three systems are A-subtype contact binaries with mass ratios (q) of 0.47, 0.34, and 0.28, respectively. The results showed that ATO J255.8159+16.8821 exhibits the O’Connell effect, while the other two systems (CRTS J034336.4+264312 and NSVS 2669503) have a symmetric light curve. The fill-out factors of the systems were determined to be 0.204, 0.157, and 0.069, respectively, indicating all three systems are shallow contact systems. To understand their evolutionary status, mass-luminosity and mass-radius diagrams were plotted. These diagrams indicate that the primary components of the three systems are main sequence stars, whereas the less massive stars have evolved beyond the main sequence. The dynamical evolution of the systems is also discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Short period contact binary systems of the W Ursae Majoris (W UMa) type represent a significant fraction of eclipsing binaries observed in the Galaxy1,2. These systems typically consist of two late-type stars3,4 Both stars fill or even exceed their Roche lobes5. Occasionally, contact binaries are observed in the early stages of their interaction, known as the shallow contact or pre-contact phase. Shallow contact systems are those systems that have a fill-out ratio \(f < 25\%\). This phase provides a valuable opportunity to investigate the evolutionary status of such systems6,7,8. It is typically characterized by components with differing effective temperatures, leading to a light curve that exhibits unequal eclipse depths for the primary and secondary minima. Despite its significance, this phase remains relatively rare among observed systems. Further details on this type of binary and its evolutionary path can be found in9. Contact binary systems are classified into two subtypes based on their spectral characteristics and physical properties: the A-subtype and the W-subtype, as initially proposed by10. For A-subtype binaries, the more massive component is hotter than the less massive one, and the mass ratio (M2/M1) is generally less than 0.5, while W-subtype systems are distinguished by having the less massive component as the hotter star, and they often show continuous period changes over time.11,12. Contact binary systems with low mass ratios are believed to be potential progenitors of unusual stellar types, including FK Comae stars and blue stragglers13,14. If the mass ratio decreases below a critical theoretical limit (\(q_{\textrm{min}}\)), the system may undergo Darwin instability15,16, resulting in the merging of binary components into a single star.17 found that this threshold can be as low as \(q = 0.044\). Conversely,18 reported that the mass ratio in contact binaries can reach values as high as 0.72, a regime where the efficiency of energy transfer is lower compared to systems with the same luminosity ratio but different configurations. Furthermore, these systems are thought to be magnetically active, showing asymmetry in the shape of their light curves19,20,21. This phenomenon is usually known as the O’Connell effect22.

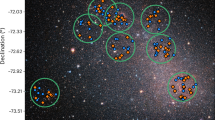

In the present study, we introduce photometric light curve analysis of three overcontact systems, \(ATO J255.8159+16.8821\) (hereinafter ATO J255), \(CRTS J034336.4+264312\) (hereinafter CRTS J034), and NSVS2669503 (hereinafter NSVS 266). The three systems were selected based on the criteria of systems having a short period (i.e., < 0.3 days) to better understand the physical parameters and evolutionary status of systems near the Contact binary period cut-off and their visibility at the Kottamia Astronomical Observatory (KAO) during our access time of the telescope. Of the three systems, CRTS J034 and ATO J255 are analyzed for the first time in this study. While NSVS2669503 is previously introduced by23, a new CCD photometric observation and more detailed analysis are reported in our study.

The system \(ATO J255.8159+16.8821\) (also known as 2MASS J17031584+1652559 and ZTF J170315.83+165255.5) has been classified as an EW-type eclipsing binary by the Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF;24), with a visual magnitude of \(15^{\textrm{m}}.667\) and an orbital period of \(0^{\textrm{d}}.2517454\). \(CRTS J034336.4+264312\) (also identified as ATO J055.9018+26.7202 and ZTF J034336.43+264312.9) was classified as an EW-type system by the Catalina Real-Time Transient Survey (CRTS;25), exhibiting a visual magnitude of \(16^{\textrm{m}}.01\) and an orbital period of \(0^{\textrm{d}}.252665\). On the other hand, NSVS2669503 (2MASS J12501739+5231350, ZTF J125017.31+523134.5) was classified as a W UMa-type (EW-type) contact binary by26. The system was also identified as an EW-type eclipsing binary by automated variable star classification in the Northern Sky Variability Survey (NSVS;26), with a visual magnitude of \(13^{\textrm{m}}.69\) and an orbital period of \(0^{\textrm{d}}.234003\). Photometric data for the system were presented in the Catalina Surveys Data Release 1 (CSS-DR1;25).23 performed a photometric study for the system and derived its orbital parameters.

The main aim of this work is to estimate the physical and absolute parameters of the three systems using new CCD photometric observations carried out by the 1.88-m telescopes at KAO as well as archival data. This analysis will help understand their evolution within the contact binary systems.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 describes the photometric observations and data reduction procedures. Section 3 presents the analysis of the period changes. Section 4 provides the results and discussion, including light curve solutions, calculations of absolute parameters, and the evolutionary status of the studied systems. Finally, Section 5 summarizes the findings and presents the conclusions.

Observations and data reduction

KAO observations

New photometric observations were carried out over several nights in 2024 for the three systems in the V, R, and I filters, using the Kottamia Faint Imaging Spectropolarimeter (KFISP) attached to the Cassegrain focus of the 1.88-m telescope at the Kottamia Astronomical Observatory (KAO)27. KAO observatory is located at an elevation of 476 meters above sea level, with coordinates of \(29^\circ 55^\prime 35.24^{\prime \prime }\) N and \(31^\circ 49^\prime 45.85^{\prime \prime }\) E. The observations were conducted using a \(2\text {k} \times 2\text {k}\) CCD camera attached to the KFISP spectropolarimeter27. The CCD camera was cooled to an average operating temperature of \(-120^\circ\)C to minimize thermal noise. A binning mode \(2 \times 2\) was applied to enhance the signal-to-noise ratio. The filter set used followed the standard Johnson-Cousin photometric system. A detailed log of the KAO observations, including dates, exposure times, and the number of frames, is presented in Table 1.

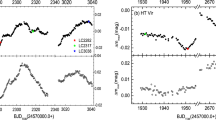

Data reduction of raw CCD images was performed using the C-Munipack package, https://c-munipack.sourceforge.net/, where bias subtraction and flat-field correction were applied to the images following the standard method. C-Munipack provides a complete solution for the reduction of CCD images. It is particularly aimed at observations of variable stars. The magnitudes of the variable, comparison, and check stars in each frame were extracted using aperture photometry methods incorporating standard DAOPHOT procedures28. Differential photometry was performed with respect to comparison and check stars, and all times were corrected to HJD. Table 2 lists the journal of the variable, comparison, and check star for each system. Magnitudes were obtained from the Guide Star Catalogue, while coordinates were retrieved from Gaia DR329. Figure 1 displays the measured light curves of the three systems in the Johnson V, R, and I filters, illustrated as normalized flux versus phase. The corresponding lower sub-panels in each plot display the differential magnitudes between the comparison and check stars, serving as a consistency check for the stability of the comparison star and the quality of the photometric observations.

ZTF and TESS observations

Additional archival data were gathered to enhance the reliability of the light curve analysis.

For the three systems, we retrieved observational data from the Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF) databases, which are available through the ZTF DR23 PublicReleases https://www.ztf.caltech.edu/ztf-public-releases.html. The ZTF observations were conducted using the g and r filters. The light curves were created using measurements from calibrated catalogs of single exposures derived by fitting the point spread function (PSF) to ensure no contamination from nearby systems30. More details on ZTF data reduction can be found in the study by31.

In addition to ZTF data we searched for available photometric observations of our systems in the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS). TESS, a NASA mission aimed at detecting transiting exoplanets through an all-sky survey, provides both light curves and full-frame image cutouts, with photometric data processed into magnitudes32. We retrieved TESS data (HLSP mission) with an exposure time of 200 seconds for the NSVS 266 system from the MAST data archive (https://archive.stsci.edu/missions-and-data/tess). However, the available data for ATO J025 were insufficient to obtain a reliable fit, and no TESS data were available for CRTS J034.

Eclipsing times and orbital period variation

For each system, we identified the primary and secondary times of minima for the V, R, and I filters using the method outlined by33, as presented in Table 3. The resultant light minimum times of the three systems are the averages of the light minimum times in the observed bands. The periods of the three systems were obtained from the literature. Based on our estimations of the times of light minima and the available periods, the new ephemerides for each system are given by the following equations:

For NSVS 266, we collected all the available data on light minimum times from the literature. There are 4 light minimum times of NSVS 266 reported in the literature by23, 8 from TESS data, and 2 minimum, including primary and secondary, observed by us. These minima are listed in Table 4, where the epoch, calculated from the ephemeris extracted from TESS data HJD(min) = 2453338.922367, and the period is 0.23400259\(\phantom{0}^{d}\).

In Table 4, the parameter O–C is defined as the difference between the minimum time of observation and the calculation. In order to study the period variation, we plotted the (O–C)\(\phantom{0}_{primary}\) versus the number of integer cycles (E) in Fig. 2, which shows an obvious upward parabolic trend. Therefore, we used a quadratic curve to fit this trend. The resultant quadratic ephemeris is:

This ephemeris is used to calculate the phases and draw the light curves in the V, R, and I bands, as shown in Fig. 1. The quadratic term (Q) of this equation was found to be − 2.6619 \(\times\) 10\(\phantom{0}^{-7}\), suggesting that the orbital period variation is decreasing by a rate of dP/dt 1.8485 \(\times\) 10\(\phantom{0}^{-10}\) days yr\(\phantom{0}^{-1}\).

Results and discussion

Analysis of light curves

The light curve analyses of the three systems were performed using the PyWD2015 software34. The program provides a modern graphical user interface (GUI) for the 2015 version of Wilson-Devinney (WD)35,36. The adopted parameters, like the gravity-darkening assumed to be g = 0.325, and the bolometric albedo coefficients were fixed as A = 0.537 for both components as appropriate for stars with convective envelopes. The limb-darkening coefficients were derived using the logarithmic law and interpolated from the tabulated values of38, which are appropriate for over-contact binary systems. The same coefficients were applied to both components, meaning the linear and non-linear limb-darkening coefficients were set equal: \(x_1 = x_2\) and \(y_1 = y_2\).

Several methods have been employed in previous studies to calculate the effective temperature of the primary component. Since these approaches often yield varying results, we applied three distinct methods to estimate the effective temperature of the primary component in the studied systems. To improve reliability, we adopted the average of the three estimates as the final value. First, we used the infrared color index (J-H) from the 2MASS catalog and applied Collier’s equation39. Second, we utilized the period-temperature relation described by40. Third, we retrieved temperature estimates from Gaia29,41. Table 5 summarizes the temperature values derived from each method and the calculated mean value.

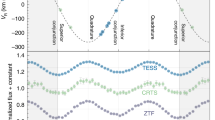

Since there were no available spectroscopic radial velocity measurements for the systems, we adopted the q-search method to determine each system’s mass ratio \(q(M_2/M_1)\). This method assigns a specific value to q while allowing the other parameters to vary. Figure 3 displays the relationship between the mass ratio (q) and the mean residual of each system of input parameters. The best q values for ATO J255, CRTS J034, and NSVS 266 were found to be around 0.48, 0.34, and 0.28, respectively.

The adjustable parameters in this model are the inclination of the orbit (i), the potentials (\(\Omega _1\), \(\Omega _2\)), the luminosity of the primary (\(L_1\)) in each passband, and the temperature of the secondary (\(T_2\)). Based on the shape of the systems’ light curves, we performed the fits using the overcontact configuration (mode 3), which is suitable for overcontact systems that are not in thermal contact, evidenced by the unequal depths (i.e., temperatures) of the minima.

Figure 4 shows the best fit between the models and observations for ATO J255, CRTS J034, and NSVS 266. The solutions show an unequal maximum for the ATO J255 system, which may be attributed to the O’Connell effect22. This effect is explained by the presence of a cold spot on the primary component of the ATO J255 system (likely caused by magnetic activity in the more massive component). This asymmetry was observed in our data but was not evident in the ZTF archival data. Tables 6,7 and 8 list the solution parameters obtained in the Johnson VRI and ZTF gr filters for ATO J255, CRTS J034, and NSVS 266, respectively. For NSVS 266, results based on TESS data are also included.

The accepted W-D parameters were then used to illustrate the three-dimensional configurations of the systems using the PyWD2015 software. Figure 5 shows the over-contact configuration for the three systems with a degree of fill-out as f = 0.204, 0.157, and 0.069 for ATO J255, CRTS J034, and NSVS 266, respectively.

Our solution represents the first analysis of ATO J255 and CRTS J034, while the NSVS 266 system was previously studied by23. Comparing our results with those of23, we found a difference in the effective temperature of the primary component due to the different methods used. While we calculated \(T_1\) as the average of three distinct approaches,23 only used the method of39. However, the temperature difference between \(T_1\) and \(T_2\) in both studies remains nearly the same, and there are no significant discrepancies in other parameters such as mass ratio (q), potential (\(\Omega\)), and luminosity of the primary component (\(L_1\)). while23 solved the light curve by incorporating a hot spot on the secondary component. However, the difference between the two maxima in our observations is not significantly large and falls within the observational error range for both ZTF and Kottamia observations. Therefore, we are unable to definitively attribute this asymmetry to the O’Connell effect.

Best theoretical fit (solid line) obtained from light curves analysis together with observed light curves (points) of ATO J255 (top), CRTS J034 (middle), and NSVS 266 (bottom). The left panels show the light curves in the Johnson filters, while the right panels represent the light curves in the ZTF g and r filters. For NSVS 266, an additional light curve obtained using the TESS filter is also included.

Absolute parameters and evolutionary state

We computed the absolute parameters of the three systems following the procedure of42,43,44 as follows: The mass of the primary component (\(M_1\)) for each system was calculated following45.

where P is the period of the system. The secondary (\(M_2\)) mass is computed using the mass ratio from the light curve solution. Using Kepler’s third law, we computed the semi-major axis a(\(R_\odot\)). Then, the radius (R) of the star is calculated from the relation

Where \(r_{mean}\) outcomes from the light curve solution (\(r_{mean} = (r_{back} * r_{side} * r_{pole})^{1/3}\) ). Knowing the effective temperature and radius, we can use the Stefan-Boltzmann law to calculate the luminosity (L) of the components as follows:

The bolometric magnitude (\(M_{bol}\)) of the star is calculated from:

Where the bolometric magnitude of the sun (\(M_{bol_{\odot }}\)) is 4.7346. The absolute magnitude (\(M_V\)) calculated using the following relation

Where the bolometric correction (BC) is extracted from Fowler’s tables47. The absolute parameters of the three systems are listed in Table 9. The errors in absolute parameters are calculated based on the uncertainties in the input parameters using the following equation:

Where f is the derived parameter, xi is the input parameter, \(\sigma x\) are the uncertainties in \(x_i\), and \(\delta f/\delta x\)are the partial derivatives.

The positions of the individual components of the system are shown in two diagrams: the Mass-Luminosity (M-L, upper panel) and Mass-Radius (M-R, bottom panel) relations for the Zero Age Main Sequence (ZAMS) and the Terminal Age Main Sequence (TAMS) based on48. The circles denote the primary components, while the squares represent the secondary components. These diagrams in Fig. 6 are used to assess the system’s evolutionary stage, where the primary components of the three systems are located over the main sequence while the secondary components of the three systems are out of the main sequence, which indicates that they are in the evolution stage. To further investigate the evolution of our studied systems, we compared our results with contact binary systems listed in the contact binary Catalog compiled by40 (https://wumacat.aob.rs/Stars). This catalog provides a comprehensive dataset of well-characterized contact binaries, allowing us to place our studied systems within evolutionary tracks; the contact binary sample from40 was plotted in Fig. 6 as black circles and squares for primary and secondary components, respectively. Using pre-main sequence evolutionary tracks from Bressan et al. (2012), we located primary components over the \(log T_{eff}-log L/L_\odot\) plane (Fig. 7) to verify that they are main-sequence stars. The results show that all three primary components align with the pre-main sequence track

Locations of the components of ATO J255 (red symbols), CRTS J034 (blue symbols), and NSVS 266 (green symbols), by comparison with the contact binary sample from Latkovi? (2021) on mass-luminosity (upper) and mass-radius (middle) relation (48). The circles represent the primary components, while the squares represent the secondary components.

Positions the primary component of each system on \(log T_{eff} - log L/L_\odot\) plane. Evolutionary tracks and isochrones are from49. Each track corresponds to the mass value of solar units.

The orbital angular momentum (OAM, Jo) and total mass (M) of the system are fundamental physical quantities that determine the orbital size (a) and period (P). The OAM and mass loss are the physical parameters that control the magnitude and direction of dynamical evolution, so the log Jo-log M diagram is an obvious choice for studying the dynamical evolution of binary orbits. We calculated the orbital angular momentum of the three systems using the following equation50.

where Jo is the orbital angular momentum in \(g cm^{2} s^{-1}\), q is the mass ratio, M is the total mass of the binary, P is the orbital period, and G is the gravitational constant. The three binaries have logJo values 51.4660 (ATO J255), 51.3226 (CRTS J034), and 51.5414 (NSVS 266) in the cgs system. In Fig. 8, we plot the orbital angular momentum against the total mass distribution. By placing our studied systems on this diagram alongside the known contact binary systems of51, we found that the three systems follow the same trend as the known contact binaries. They lie within the contact region, below the quadratic boundary line defined by50, as expected for contact binary systems.

The period-color (or temperature) relationship (Eggen 1967;37) is a well-established correlation for contact binaries. All EW-type eclipsing binaries listed in the variable star index (VSX) exhibit a period distribution consistent with the relative period distribution of EWs identified through LAMOST low-resolution spectroscopy (LRS). This similarity suggests that LAMOST contact binaries can be effectively used to study the overall properties of EWs. Given the correlation between orbital period and effective temperature observed in 8,510 contact binaries by LAMOST, the majority of EWs fall within the normal EW limits defined by52. Figure 9 presents the period-temperature distribution for contact binaries, with the three studied systems plotted on the \(P-log T\) diagram. Their positions lie between the two boundary lines (dashed red lines), indicating that they are likely normal contact binaries.

Conclusions

In the present study, we report new light curves for three eclipsing binary systems, ATO J255, CRTS J034, and NSVS 266, based on recent observations conducted at the Kottamia Astronomical Observatory, as well as archival data obtained from the Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF) and the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS). Through detailed light curve modelling, we have derived the physical parameters of the three systems. New times of minima for all three systems have been calculated. In particular, for NSVS 266, we performed an O-C (Observed-Calculated) analysis to investigate period variations. The results indicate a decreasing orbital period, with a rate of \(\textrm{d}P/\textrm{d}t \approx 1.85 \times 10^{-10}\) days yr\(\phantom{0}^{-1}\).

Based on the systems’ mass ratios and surface temperatures, we classified all three as A-subtype W UMa contact binaries. Contact binaries are typically categorized by their fill-out factor into three groups: deep contact (\(f \ge 50\%\)), medium contact (\(25\% \le f < 50\%\)), and shallow contact (\(f < 25\%\)) systems53. According to this classification, ATO J255, CRTS J034, and NSVS 266 are all shallow contact systems, with fill-out factors of 0.204, 0.157, and 0.069, respectively. The light curve of ATO J255 displays an O’Connell effect, which we attribute to the presence of a cool spot on the primary component. This feature provides insight into magnetic activity and starspot evolution in contact binary systems. However,54 reported that the accuracy of the mass ratio (q) becomes less reliable as the eclipses change from total to partial. This suggests that the value of q obtained for ATO J255 is likely more accurate than those for CRTS J034 and NSVS 266. Nevertheless, we think that high-quality photometric observations can still lead to reasonably accurate determinations of q, even in systems with partial eclipses.

Using the derived mass ratios and a set of empirical relations, we estimated the absolute physical parameters of the three systems. These parameters are expected to be more reliable for ATO J255, while CRTS J034 and NSVS 266 would benefit from additional spectroscopic observations to improve parameter accuracy. A better understanding of the physical and evolutionary states of these systems requires precise measurements of absolute parameters such as mass, radius, and luminosity. Our photometric estimates provide an initial approximation of their evolutionary stages. The positions of the components on mass-luminosity and mass-radius diagrams suggest that the primary components remain on the main sequence, whereas the secondary components exhibit signs of evolution. To assess the reliability of our results, we compared the absolute parameters of our systems with a well-characterised sample of contact binaries from40. The components of our systems follow the same general trends as those in the comparison sample, supporting the validity of our derived parameters. Moreover, the calculated angular momentum values further confirm the classification of these systems as contact binaries.

The current study contributes to future observational and theoretical studies, particularly in binary star stability and mass transfer dynamics. Future spectroscopic studies are recommended to refine the estimates of mass, temperature, and radial velocity curves, thereby enhancing our understanding of the internal structure and evolutionary status of these systems.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request The data that supports the findings of this study is available at ZTF Public Releases (https://irsa.ipac.caltech.edu/Missions/ztf.html).

References

Jayasinghe, T. et al. The ASAS-SN catalogue of variable stars - VII. Contact binaries are different above and below the Kraft break. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society493, 4045–4057, https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/staa518 (2020). arXiv: 1911.09685.

Shapley, H. The relative frequency of low luminosity eclipsing binaries. Harv. Obs. Monogr. 7, 249 (1948).

Kopal, Z. The classification of close binary systems. Ann. d’Astrophys. 18, 379 (1955).

Abdel Rahman, H. I. & Darwish, M. Physical characterization of late-type contact binary systems observed by LAMOST: a comprehensive statistical analysis. Sci. Rep. 13, 21648. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-48507-5 (2023).

Lucy, L. B. & Wilson, R. E. Observational tests of theories of contact binaries. Astrophys. J. 231, 502–513. https://doi.org/10.1086/157212 (1979).

Darwish, M. S., Abdelkawy, A. G. & Shokry, A. Multi-band photometric study of the short period eclipsing binary ato j00. 0177+43.4841: physical properties and evolutionary status. Eur. Phys. J. Plus. 140, 74 (2025).

Yildirim, M. F., Aliccavucs, F. & Soydugan, F. CN Andromedae: a shallow contact binary with a possible tertiary component. Res. Astron. Astrophys. 19, 010. https://doi.org/10.1088/1674-4527/19/1/10 (2019).

Samec, R. G., Flaaten, D., Kring, J. & Faulkner, D. R. BVRcIcObservations and analysis of the near-contact solar type eclipsing binary, V530 Andromedae. ISRN Astron. Astrophys. 2013, 201235. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/201235 (2013).

Stkepie’n, K. & Kiraga, M. Evolution of cool close binaries-rapid mass transfer and near contact binaries. Acta Astron.63 (2013).

Binnendijk, L. The orbital elements of W Ursae Majoris systems. Vistas Astron. 12, 217–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/0083-6656(70)90041-3 (1970).

Yildiz, M. & Doğan, T. On the origin of W UMa type contact binaries a new method for computation of initial masses. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 430, 2029–2038. https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/stt028 (2013).

Li, K. et al. Photometric Study and Absolute Parameter Estimation of Six Totally Eclipsing Contact Binaries. 162, 13, https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-3881/abfc53 (2021). arXiv: 2104.13759.

Rasio, F. A. The Minimum Mass Ratio of W Ursae Majoris Binaries. 444, L41, https://doi.org/10.1086/187855 (1995). arXiv: astro-ph/9502028.

Qian, S., Yang, Y., Zhu, L., He, J. & Yuan, J. Photometric Studies of Twelve Deep. Low-mass Ratio Overcontact Binary Systems. 304, 25–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10509-006-9114-z (2006).

Huang, S.-S. A theory of the origin and evolution of contact binaries. Ann. d’Astrophys. 29, 331 (1966).

Hut, P. Stability of tidal equilibrium. Astron. Astrophys. 92, 167–170 (1980).

Yang, Y.-G. & Qian, S.-B. Deep, low mass ratio overcontact binary systems XIV. A statistical analysis of 46 sample binaries. Astron. J. 150, 69. https://doi.org/10.1088/0004-6256/150/3/69 (2015).

Csizmadia, S. & Klagyivik, P. On the properties of contact binary stars. Astron. Astrophys. 426, 1001–1005. https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361:20040430 (2004).

Darwish, M. S. et al. Kottamia 74-inch telescope discovery of the new eclipsing binary 2MASS J20004638 + 0547475 First CCD photometry and light curve analysis. New Astron. 53, 35–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.newast.2016.11.009 (2017).

Gazeas, K. et al. Physical parameters of close binary systems VIII. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 501, 2897–2919. https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/staa3753 (2021).

Shokry, A. et al. New CCD photometry and light curve analysis of two WUMaBinaries: 1SWASP J133417.80+394314.4 and V2790 Orion. New Astron. 80, 101400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.newast.2020.101400 (2020).

O’Connell, D. J. K. The so-called periastron effect in close eclipsing binaries; New variable stars (fifth list). Publ. Riverv. Coll. Obs. 2, 85–100 (1951).

Lu, H.-P., Michel, R., Zhang, L.-Y. & Castro, A. Magnetic activity and period variation studies of the short-period eclipsing binaries III V1175 Her, NSVS 2669503, and 1SWASP J133417.80+394314.4. Astron. J. 156, 88. https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-3881/aad001 (2018).

Chen, X. et al. The Zwicky transient facility catalog of periodic variable stars. Astrophys. J. Suppl. 249, 18. https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4365/ab9cae (2020).

Drake, A. J. et al. The Catalina surveys periodic variable star catalog. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 213, 9. https://doi.org/10.1088/0067-0049/213/1/9 (2014).

Hoffman, D. I., Harrison, T. E. & McNamara, B. J. Automated variable star classification using the northern sky variability survey. Astron. J. 138, 466–477. https://doi.org/10.1088/0004-6256/138/2/466 (2009).

Azzam, Y. A. et al. Kottamia faint imaging spectro-polarimeter (KFISP): Opto-mechanical design, software control and performance analysis. Exp. Astron. 53, 45–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10686-021-09802-z (2022).

Tody, D. IRAF in the Nineties. In Hanisch, R. J., Brissenden, R. J. V. & Barnes, J. (eds.) Astronomical Data Analysis Software and Systems II, vol. 52 of Astronomical Society of the Pacific Conference Series, 173 (1993).

Gaia Collaboration. VizieR Online Data Catalog: Gaia DR3 Part 1. Main source (Gaia Collaboration, 2022). VizieR On-line Data Catalog: I/355. Originally published in: Doi: https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-63,https://doi.org/10.26093/cds/vizier.1355 (2022).

Heasley, J. N. Point-spread function fitting photometry. In Craine, E. R., Crawford, D. L. & Tucker, R. A. (eds.) Precision CCD Photometry, vol. 189 of Astronomical Society of the Pacific Conference Series, 56 (1999).

Masci, F. J. et al. The Zwicky transient facility: Data processing, products, and archive. 131, 018003, https://doi.org/10.1088/1538-3873/aae8ac (2019). arXiv: 1902.01872.

Ricker, G. R. et al. The transiting exoplanet survey satellite. In MacEwen, H. A. et al. (eds.) Space telescopes and instrumentation 2016: Optical, infrared, and millimeter wave, vol. 9904 of Society of Photo-Optical Instrumentation Engineers (SPIE) Conference Series, 99042B, https://doi.org/10.1117/12.2232071 (2016).

Kwee, K. K. & van Woerden, H. A method for computing accurately the epoch of minimum of an eclipsing variable. Bull. Astron. Inst. Neth. 12, 327 (1956).

Güzel, O. & Özdarcan, O. PyWD2015 - A new GUI for the Wilson-Devinney code. Contrib. Astron. Obs. Skalnate Pleso 50, 535–538. https://doi.org/10.31577/caosp.2020.50.2.535 (2020).

Wilson, R. E. & Devinney, E. J. Realization of accurate close-binary light curves: Application to MR Cygni. Astrophys. J. 166, 605. https://doi.org/10.1086/150986 (1971).

Wilson, R. E. Accuracy and efficiency in the binary star reflection effect. Astrophys. J. 356, 613. https://doi.org/10.1086/168867 (1990).

Rucinski, S. M. Contact binaries of the galactic disk: Comparison of the Baade’s window and open cluster samples. Astron. J. 116, 2998–3017. https://doi.org/10.1086/300644 (1998).

van Hamme, W. New limb-darkening coefficients for modeling binary star light curves. Astron. J. 106, 2096. https://doi.org/10.1086/116788 (1993).

Collier Cameron, A. et al. Efficient identification of exoplanetary transit candidates from SuperWASP light curves. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 380, 1230–1244. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2966.2007.12195.x (2007).

Latković, O., Čeki, A. & Lazarević, S. Statistics of 700 individually studied W UMa stars. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 254, 10. https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4365/abeb23 (2021).

Collaboration, Gaia et al. Gaia data release 2. Summary of the contents and survey properties. Astron. Astrophys. 616, A1. https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201833051 (2018).

Poro, A. et al. Two-dimensional parameter relationships for W UMa-type systems revisited. Res. Astron. Astrophys. 24, 015002. https://doi.org/10.1088/1674-4527/ad0866 (2024).

Darwish, M. S. & Abdelkawy, A. G. A. Light curve modeling of the two short period eclipsing binaries ATO J009.3383 + 342329 and CRTS J004004.7 + 385531. Phys. Scr. 99, 035021. https://doi.org/10.1088/1402-4896/ad265d (2024).

Darwish, M. S., Abdelkawy, A. G. A. & Hamed, G. M. Light curve analysis and evolutionary status of four newly identified short-period eclipsing binaries. Sci. Rep. 14, 3998. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-54289-1 (2024).

Gazeas, K. D. Physical parameters of contact binaries through 2-D and 3-D correlation diagrams. Commun. Asteroseismol. 159, 129–130 (2009).

Prša, A. et al. Nominal values for selected solar and planetary quantities: IAU 2015 Resolution B3. 152, 41, https://doi.org/10.3847/0004-6256/152/2/41 (2016). arXiv: 1605.09788.

Flower, P. J. Transformations from Theoretical Hertzsprung-Russell diagrams to color-magnitude diagrams: effective temperatures, B-V colors, and bolometric corrections. Astrophys. J. 469, 355. https://doi.org/10.1086/177785 (1996).

Pols, O. R., Schröder, K.-P., Hurley, J. R., Tout, C. A. & Eggleton, P. P. Stellar evolution models for Z = 0.0001 to 0.03. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 298, 525–536. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-8711.1998.01658.x (1998).

Bressan, A. et al. PARSEC: Stellar tracks and isochrones with the PAdova and TRieste Stellar Evolution Code. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 427, 127–145. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2966.2012.21948.x (2012).

Eker, Z., Demircan, O., Bilir, S. & Karataş, Y. Dynamical evolution of active detached binaries on the logJ\(\phantom{0}_{o}\)-logM diagram and contact binary formation. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 373, 1483–1494. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2966.2006.11073.x (2006).

Poro, A. et al. Estimating the absolute parameters of W UMa-type binary stars using Gaia DR 3 parallax. New Astron. 110, 102227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.newast.2024.102227 (2024).

Qian, S.-B. et al. Contact binaries at different evolutionary stages. Res. Astron. Astrophys. 20, 163. https://doi.org/10.1088/1674-4527/20/10/163 (2020).

Li, K. et al. (2022) Extremely Low Mass Ratio Contact Binaries. I. The First Photometric and Spectroscopic Investigations of Ten Systems. Astron J. 164, 202, https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-3881/ac8ff2

Terrell, D. & Wilson, R. E. Photometric mass ratios of eclipsing binary stars. Astrophys. Space Sci. 296, 221–230. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10509-005-4449-4 (2005).

Acknowledgements

This paper is based upon work supported by the Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) under grant number 45779. We are very grateful to the team of Kottamia Astronomical Observatory for the helpful discussion. The research has made use of ZTF observations. The authors acknowledge, I. Elhosiney, M. Abdelkrim, and W. Badawy for their helpful sharing of Kottamia observations. This research has been made using the SIMBAD and VizieR databases operated by the Centre de Données Astronomiques (Strasbourg). This publication makes use of data products from the Zwicky Transient Facility data (ZTF).

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.S. conceived the idea of the study; M.E. and I.Z. collected the data. A.S. and M.D. performed the light curve analysis using PYWD2015. G.H. extracted the Roch lobe configuration using PYWD2015. A.S. prepared figures. A.S. collectively analyzed the results. A.S wrote the main manuscript. A.T. and M.D reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shokry, A., Darwish, M.S., El-Sadek, M.A. et al. Photometric light curve analysis of three overcontact binary systems: ATO J255.8159+16.8821, CRTS J034336.4+264312, and NSVS 2669503. Sci Rep 15, 28369 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12402-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12402-y