Abstract

Acerola (Barbados cherries) has become a highly traded superfruit because it contains many phytonutrients and is a good source of vitamin C. The fruits of Malpighia glabra, and M. emarginata are utilized in food products, dietary supplements and natural health products. However, there are differences among the fruit of Malpighia species with respect to phytochemicals, nutrient value and clinical research. Furthermore, there is evidence of adulteration with other fruit such as cherries (Prunus spp.). Unfortunately, conventional morphological examination does not distinguish acerola fruit species. Furthermore, no published methods are available to distinguish the fruits of these species including chemical and DNA based techniques. This risk to quality assurance (QA) is increased when considering processed berries into juice or powdered ingredients of which are the most common source for manufactures. This lack of QA methods also increases the risk of adulteration with cheaper fruit from other species. The goal of this research is to provide orthogonal molecular methods to authenticate Acerola fruit ingredients and discuss the benefits and constraints of these two different methods. This research supports quality assurance (QA) programs with fit-for-purpose methods for verifying the authenticity of acerola species ingredients from suppliers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The superfruit market has had significant growth in the marketplace putting demand on suppliers. Consumer demand for superfoods such as superfruit is increasing and attracting the attention of multiple industry sectors including food products, dietary supplements and natural health products1. Industry has responded to this demand by marketing their products with claims that superfoods mitigate ailments and promote considerable health benefits2,3. The superfruit market alone was valued at 140.3 billion USD in 2025 and is expected to grow over 200 billion USD in the next decade4. This is partly driven by the demand from contemporary consumers that value a healthier and environmentally friendly source of nutrition. Superfoods are highly nutritional with bioavailable nutrients and documented bioactivity within the body due to the concentration of nutrients5. Few fruits meet the criteria of high nutrient value with notable nutrients such as vitamin C and can be sourced at a reasonable cost by large manufactures that focus on global markets.

Acerola berries are designated as a superfruit that can be sustainably grown by producers and sourced in large quantities in the marketplace6. Acerola berries are also known as Barbados cherry and West Indian cherry and are grown commercially as small trees or shrubs. Taxonomically there are two species (Malpighia glabra L.; Malpighia emarginata DC.) from the family Malpighiaceae that contain 45 species7,8. There is mention in the literature of another commercial species Malpighia punicifolia L., which is a synonym for Malpighia glabra. The fruit of these two species is indistinguishable as a red fleshy drupe that produces a juicy acidic pulp. The common names are used inconsistently for the respective species causing some confusion when sourcing acerola ingredients from the global supply chain9. Malpighia glabra is native to the Americas, including Mexico, Central America, South America, and the Caribbean with more recent introduction and cultivation in USA (Florida, California, Texas), Cuba, Jamaica, and Puerto Rico. Malpighia emarginata is originally from Mexico in the Yucatán peninsula, but is now cultivated in Central America, the Caribbean, and South America as far south as Peru10,11 Brazil is the world’s largest producer of acerola berries with most of the production in the northeast states of Pernambuco, Paraíba, Bahia, and Ceará6,12. Both species have been introduced for cultivation in Southeast Asia and southern India. In India, cultivation is reported in backyard gardens across the states of Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Kerala and Maharashtra. More recently production has been recorded in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands13. Production is relatively small in the southern USA. The largest markets for acerola products include United States, Germany, France, and Japan.

Acerola fruit has considerable nutritional and health benefits. There is a plethora of research on acerola to support pharmacological, medicinal and nutritional claims of which have been well documented in several scientific reviews1,6,14. Acerola health benefits include high antioxidant capacity7,15,16antitumor17antimutagenic18,19,20,21,22,23antidiabetic24hepatoprotective25 and functional properties like skin anti-aging26skin whitening, and multidrug resistant reversal activity12,27. This body of research is supported by many biochemistry studies that have recorded significant phytonutrients such as flavonoids, anthocyanins, carotenoids, phenolics, benzoic acid derivatives and phenylpropanoids within comprehensive scientific reviews28,29. The presence of these bioactive compounds provides multiple hypothetical mechanisms to support the numerous health claims27,28. This includes various biological activities using in vitro and in vivo models in which probable mechanisms have been determined14. One of the most studied areas of research underpins the claim that acerola is one of the richest natural sources of ascorbic acid up to 100 times more than that of oranges and lemons14,30,31,32. It has been reported that the vitamin C of acerola is more easily absorbed than other forms including synthetic ascorbic acid27,33. Acerola berries are consumed and prepared as a nutritional drink and traditional remedy in Brazil. In Europe (e.g., France, Germany, and Hungary) the fruit is utilized as juice, whilst in multiple forms within the United States where it is consumed as a rich source of ascorbic acid (vitamin C) within supplements and natural health products27.

There is a lack of published research on quality assurance tools in the acerola industry. These QA tools are needed to ensure species ingredient authenticity and prevent adulteration with other cheaper fruit species. Morphological techniques are inadequate because they cannot differentiate among the species of Malpighia that are traded as berries. DNA-based markers have become a popular method for identifying and verifying botanical ingredients. This is because the genetic makeup of each species is unique, regardless of factors such as sample age, physiological condition, environmental growth conditions, harvesting methods, storage, and processing34. The DNA extracted from the fruit, leaves, stems or roots of plants all carry the same genetic sequences of which can be stored for long periods of time as they are stable35. Multiple DNA regions have been utilized to develop specific markers for identifying and authenticating botanical ingredients36,37. Several recent reviews provide the benefits and challengers of using DNA-based methods for quality assurance of botanical ingredients38,39,40,41. The use of chemical authentication has been used extensively for quality assurance of botanical ingredients42. Traditional analytical chemistry methods are well established and the advantages and limitations are discussed in numerous publications43,44,45. More advanced methods have been utilized providing rigorous approach to quality assurance of highly processed and mixtures of botanical ingredients that overcomes the challenges of traditional analytical methods46,47,48. The development of orthogonal molecular methods for ingredients with degraded DNA in processed samples allows an alternative for quality assurance testing using metabolomic methods such as nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR)49,50,51,52,53,54. The use of phytochemical analysis and metabolomics methods such as chemical profiling by NMR are fit-for-purpose in identifying the active ingredients labelled on herbal products55,56. Analytical chemistry and DNA methods are not fit-for-purpose when evaluating complex samples, such as herbal dietary supplements that can include a mixture of several plant species in one product36,43,54,57. Next generation sequencing has been suggested as DNA-based tool for admixtures, but there are considerable challenges preventing this method application including: requirement for high quality DNA, sensitivity issues (contamination), quantification inaccuracy, need for complex bioinformatics, reference database limitations, inter-species DNA competition, PCR bias and primer limitations58,59,60. Traditional analytical chemistry utilizes targeted methods for each molecule of interest. Most QA requirements need to assess several molecules of interest requiring a multi-test approach costing considerable time and funding. Analytical chemistry methods are limited by ingredients that are mixtures of species due to several critical issues including: similarity in chemical signatures, incomplete profiling, chemical marker dependence, and processing induced variation causing inconsistent results43,48. NMR methods overcome many of these barriers and have a wide range of applications in food and botanical industry, as ingredients authentication and quantification, including active ingredient quantification and differentiating the geographic origins ingredients61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68. NMR fingerprints use many metabolites to identify species overcoming the barrier of traditional analytical chemistry analysis that focuses on a single molecule that is not species specific44. The extraction methods used to acquire metabolite profiles are robust providing consistent NMR fingerprints with sufficient variation to discriminate species and sometimes geographic variants63,64,65,66,67,68. Although NMR methods cannot be used to identify multiple species in a mixture, it can be used to identify the existence of an unknown adulterant species. This is because NMR fingerprints are specific to each species ingredient and the fingerprint would be considerably different if another species was added. These molecular methods need to be assessed in the context of specific species ingredients to determine fit-for-purpose in the quality assessment of sourced botanical ingredients.

The objective of this study is to develop of Nuclear Magnetic Resonance fingerprints and DNA sequence methods to distinguish Acerola species (Malpighia glabra, M. emarginata) for quality assurance of Food, dietary supplements and natural health products. More specifically we used two methods including, (1) DNA sequencing the ITS nuclear region for 16 samples and, (2) 1 H-NMR metabolite fingerprinting to analyze 16 samples consisting of 10 samples of two Acerola species (Malpighia glabra, M. emarginata) and 6 samples of common adulterant cherry (Prunus spp.) species. The validation of genomics and metabolomics approaches in this study may be valuable tool for quality assurance assessment of both product identity and purity.

Materials and methods

Botanical samples

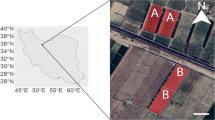

This study developed two separate orthogonal methods using 32 Samples including, (1) DNA sequencing of 16 samples representing two acerola species (Malpighia glabra, M. emarginata) of which 13 were leaf samples and 3 were berry samples (Table S1), and (2) NMR metabolite fingerprinting of 16 samples representing 10 berry samples of two acerola species (Malpighia glabra, M. emarginata) and 6 berry samples of cherry representing two species (Prunus cerasus L.; Prunus avium (L.) L.) (Table S2). Only berry samples were used for NMR metabolite fingerprinting representing the form of acerola product in the supply chain because NMR fingerprints are known to be different among leaves and fruit69,70. It is known that DNA sequences for specific regions such as ITS do not change for different tissues such as leaves and fruit. Therefore, we used mostly leaves in this study for DNA sequencing. However, we did sequence five vouchers (e.g., leaves and berries) from the NMR study including samples for each Malpighia species to verify that the berries used for NMR metabolite fingerprinting were the correct species (Table S1). We did not attempt to sequence the cherry samples due to the known challenges of barcoding cherry (Prunus spp.) in the published literature including ITS and other regions71,72,73. The identification of the herbarium voucher samples was confirmed by qualified taxonomist on staff at the University of Guelph; the voucher metadata are listed in supplementary Table S3. All samples are housed at the Natural Health Products Research Alliance, University of Guelph.

Genomic DNA extraction

Genomic DNA from the samples were extracted using the Nucleospin Plant II kit (Macherey- Nagel GmbH & Co. KG, Düren, Germany) to get high-quality DNA. DNA extractions were conducted using 100 mg of each sample, following the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA quantification was carried out with the QubitTM 3.0 Fluorometer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

DNA amplification of ITS

The ITS region was used because of its ability to discriminate con generic species3,74,75,76. Alternative DNA regions were considered but due to well documented limitations of other DNA regions, the ITS region was used in this study3,77,78,79. PCR was performed using species-specific ITS primer pairs as described by Fazekas et al. (2012)80. The reaction mixtures (20 µL) contained 1 U AmpliTaq Gold Polymerase, GeneAmp buffer II (100 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.3 and 500 mM KCl), 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 0.1 mM of each primer, and 20 ng of template DNA.

DNA sequencing of ITS region

The ITS amplified products were sequenced in both directions following the protocols established at the University of Guelph Genomics Facility (www.uoguelph.ca/~genomics). The products from each specimen were purified using Sephadex columns and analyzed on a ABI 3730 sequencer (Applied Biosystems). Bidirectional sequence reads were acquired for all the PCR products. The sequences were assembled using CodonCode Aligner version 11.0.1 (CodonCode Corp) and manually aligned with BioEdit version 7.0.9. Subsequently, the aligned sequences were processed using Clustal W81. The genetic distances were calculated using the Kimura2Parameter (K2P) model in Mega11 89. 18 DNA sequences from GenBank were used to assess the specificity of the ITS region and compare interspecific variation among the two species of Malpighia including, M. glabra, M. emarginata. These 18 sequences were used in a BLAST analysis within GenBank to assess the specificity of these sequences to other Malpighia species and that of any potential adulterants such as Prunus species.

NMR sample Preparation

Samples for NMR analysis were prepared by weighing 300 mg of finely ground plant tissue (Table S2). To ensure complete homogenization, the plant material was ground in liquid nitrogen using a mortar and pestle, then dissolved in a solvent mixture of 90% regular methanol and 10% deuterated methanol (CD₃OD) for its broad solubility range, which aids in NMR acquisition83,84. Each sample was prepared in triplicate for consistency, sonicated in a water bath at room temperature for 10 min to enhance extraction, and centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 5 min. Finally, 650 µL of the clear supernatant was transferred into a 5 mm Wilmad® NMR tube for spectral acquisition.

NMR spectral acquisition

The proton (¹H) NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Avance III 400 MHz spectrometer, which features a 5 mm Broadband Inverse (BBI) probe designed for room temperature use. We used a proton NOESY (Nuclear Overhauser Effect Spectroscopy) pulse sequence with pre-saturation to improve the results. This method included dual solvent suppression for both water and methanol, helping to reduce any interference from the solvent signals. The key acquisition parameters included: Spectrometer frequency: 400.3 MHz; Number of scans: 64; Acquisition time: 2.27 s; Relaxation delay: 12.73 s; Spectral width: 8223.68 Hz. The use of dual solvent suppression was utilized to improve the spectral quality by reducing peak overlap from residual solvent signals, enhancing metabolite detection in complex biological matrices85. Temperature stabilization was maintained at 300 K throughout data acquisition.

NMR data processing and analysis

In this study, NMR spectral data were processed with TopSpin 3.6.3 for consistency and accuracy, using automated phase and baseline corrections and referencing the tetramethylsilane (TMS) peak at 0.00 ppm for calibration. A rectangular binning approach with a bin width of 0.01 ppm was utilized over a chemical shift range from − 1 to 12 ppm, while residual solvent peaks corresponding to water (4.75–5.06 ppm) and methanol (3.16–3.45 ppm) were excluded to minimize spectral distortion. Each spectrum was normalized via a scaling method wherein values below the mean intensity were set to zero, and intensities above the mean were scaled to fit within a range of 1 to 100. For statistical analysis, we performed multivariate analyses, including Hierarchical Clustering Analysis (HCA) and Hierarchical Clustering on Principal Components (HCPC), based on an Euclidean dissimilarity matrix while employing Ward’s clustering method in R86. We converted spectral intensities into chemical fingerprints, which allowed us to use hierarchical clustering to distinguish between different botanical species. This NMR-based metabolomics approach provides reliable differentiation and ensures high reproducibility for future analyses.

Results

DNA extraction and sequencing

The DNA extraction protocols yielded good quality, high molecular weight genomic DNA from the dried berry and leaf samples of M. glabra and M. emarginata. The procedure yielded 40–60ng of DNA per ng/ul of leaf tissue and for a whole dried berries and powders yielded 2 to 4.5 ng/ul. The amplification of the complete ITS region (comprising ITS1, the 5.8 S rRNA gene, and ITS2) was successfully achieved using the universal primers ITS5 (forward) and ITS4 (reverse). This process generated an amplicon of approximately 700 bp for all three species investigated.

Direct sequencing of amplicon yielded a ~ 700 bp ITS sequence for M. glabra and M. emarginata. GenBank accession numbers are recorded (Table S1). Searches and BLAST analysis in GenBank indicated that the sequences of M. emarginata matched that of those in GenBank and that those sequences for M. glabra were novel and added to the GenBank library. Alignment of all the sequences revealed that there was enough interspecific variation to distinguish all the samples of M. glabra from M. emarginata. Interspecific variation among the two species was 1% including seven species specific single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within the 700 bp nucleotide sequence. Sequence variation indicated that the ITS1, 5.8 S rRNA gene and ITS2 regions of each respective species were unique. BLAST analysis revealed that all the acerola species sequences did not match any other potential adulterant species including cherry (Prunus spp.).

NMR fingerprinting

Metabolite diversity among the NMR fingerprints was considerable. Hierarchical clustering analysis (HCA) of the ¹H NMR spectral data was used to assess metabolite diversity within a heatmap of metabolite diversity (Figure: 1). The resulting dendrogram clearly distinguishes the samples of M. glabra and M. emarginata highlighting their distinct metabolite profiles. However, M. glabra exhibits closer metabolic resemblance to Prunus spp. compared to M. emarginata, suggesting a greater risk of potential adulteration. The hierarchical clustering of cherry samples groups respective Prunus species from all acerola species including distinct differences from M. glabra based on their metabolic composition. Clusters labeled A and D correspond to M. glabra and M. emarginata, respectively, while clusters B and C include Prunus spp. The distinct clustering of M. emarginata underscores its unique metabolite profile, which is markedly different from M. glabra and Prunus species. This separation suggests that while M. glabra may share some chemical characteristics with Prunus, M. emarginata remains phytochemically distinct.

Comparative ¹H NMR spectral analysis

Prunus spp. vs. Malpighia spp. ¹H NMR spectra of M. emarginata, Prunus cerasus, and Prunus avium demonstrate clear differences in metabolite distribution (Figure: S1). Although some spectral overlaps exist, there is key variation observed in the regions associated with carbohydrates (3.0–5.5 ppm), organic acids (2.0–3.0 ppm), and aromatic compounds (6.0–8.0 ppm). The most notable differences include:

-

The prominence of organic acids such as malic acid (2.4–3.0 ppm) in M. emarginata, which is significantly reduced or absent in Prunus spp.

-

Higher concentrations of ascorbic acid (4.0–4.3 ppm) in Acerola, confirming its known vitamin C content.

-

The presence of ferulic acid (6.5–7.5 ppm) in M. emarginata, a unique authentication marker absent in Prunus spp.

These spectral differences demonstrate the use of ¹H NMR fingerprinting as a reliable method for species authentication, ensuring that Malpighia species can be accurately distinguished from potential adulterants such as cherry (Prunus spp.).

Metabolite assignments and authentication markers

Elucidation of specific metabolites identifies differences among the key metabolite assignments for M. glabra and M. emarginata, respectively (Figs. 2 and 3). The assigned peaks correspond to major bioactive compounds that play a role in species differentiation (Figs. 2 and 3). The presence of ferulic acid and amino acids in M. emarginata sets it apart from M. glabra and Prunus spp. (Figs. 2 and 3).

The metabolites identified in M. glabra include α-D-glucose (5.2–5.4 ppm), β-D-glucose (4.6–4.8 ppm), fructose (4.0–4.5 ppm), ascorbic acid (4.0–4.3 ppm), and malic acid (2.4–3.0 ppm). In comparison, M. emarginata metabolites encompass ferulic acid (6.5–7.5 ppm), notably absent in Prunus spp., along with α-glucose (5.2–5.4 ppm), β-glucose (4.6–4.8 ppm), fructose (4.0–4.5 ppm), and malic acid (2.4–3.0 ppm), the latter serving as a distinguishing marker. Additionally, amino acids such as valine, leucine, and isoleucine (0.8–1.5 ppm) are specifically identified in M. emarginata31,87. These differences are considerable in the specific identification of M. glabra from M. emarginata in commercial samples.

Discussion

One of the impediments in the acceptance of herbal formulations in the medical and pharmaceutical community is the lack of standardization and quality control. This is due to unacceptable risks to human health and unjustified health claims. It is challenging to develop robust quality control parameters using analytical chemical methods because of the complex nature and inherent variability of the chemical ingredients and molecular constituents used in supplements and natural health products, (World Health Organization 2000). These challenges including that of other conventional pharmacognosy methods such as morphology, microscopy, DNA-based and phytochemical analysis have led to the demand for more robust, fit-for-purpose methods of authentication of botanical species ingredients3,88,89,90. The need for more rigorous QA methods is also driven by consumer demand that seek pure, unadulterated natural remedies and nutrition that support health lifestyles without the use of drugs and synthetic health supplements91.

There are considerable challenges in authentication of acerola species ingredients from the commercial supply chain. Our experience and collaboration with industry members working directly with procuring M. glabra and M. emarginata materials indicates that these species cannot be distinguished based on their morphology or histology. Conventional analytical chemistry methods are often providing inconclusive reports. For example, high performance thin layer chromatography (HPTLC) analysis of acerola berries of M. glabra and M. emarginata often have identical or closely overlapping profiles with similar or highly variable acerolin content depending on product processing used by different suppliers (NHPRA members pers. Comm.). More recently the industry has moved to trading fruit as dried extracts of which there is a lack of standard methods for quality assurance protocols such as reference standards and product species verification. This problem is intensified when considering that acerola is considered a superfruit in high demand due to its high vitamin C content of which is highly perishable in transit and storage92,93. Dehydrating acerola juice using a spray dryer has become a common solution in the supply industry to extend the product’s shelf life and subsequent profit margins94,95. The NHP community has repeatedly stated there is a gap in acerola quality assurance methods and need for research on the development of new methods.

This study provides two orthogonal molecular methods for the authentication of acerola species ingredients procured in the industry supply chain. The first method utilized common DNA sequencing. Several studies have used ITS sequences as genetic markers for many botanical species3,74,75,76,96. The sequence variation of ribosomal RNA gene repeats is believed to rapidly turn over thus providing considerable interspecific variation among congeneric species97. Universal PCR primers designed from highly conserved regions flanking the ITS region are available and are relatively small in size (600–700 bp) with high copy number provide relative ease of amplification of the ITS region. In our study we had successful sequencing and found sufficient variation to distinguish the two commercial acerola species. However, the materials we used contained considerable amounts of DNA unlike that of highly processed extracts, which have considerably less DNA presenting challenges for PCR and sequencing34,98. Another consideration for extract materials is the presence of PCR amplification inhibiters such as concentrated phenolic compounds, acidic polysaccharides and pigments, which can be overcome by choosing appropriate DNA extraction methods that can reduce or eliminate PCR inhibitors35. Further research is needed to develop species specific probes based on unique SNPs for M. glabra and M. emarginata that could be used within specific QPCR methods. The use of DNA probes has been successfully used for species specific verification of highly processed supplements in the form of leaf or berry extracts50,53. ITS sequences were unique to commercial acerola species and not potential adulterants such as cherry species. However, standard operating protocols aimed at authenticating target species ingredients and preventing adulteration would require full ITS sequencing, which requires considerable resources (e.g., time, cost). If the materials are highly processed extracts, then targeted QPCR would be required including specific QPCR assays for all the potential adulterants, which is resource intensive (e.g., time, cost).

In this study, ¹H Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) metabolomic fingerprinting combined with chemometric clustering distinguished all the samples for two Acerola species, M. glabra and M. emarginata, from potential adulterants belonging to the Prunus genus (Prunus cerasus and Prunus avium). The results provide a metabolic fingerprint that can serve as a scientific authentication tool based on primary and secondary metabolite composition. ¹H NMR fingerprinting, coupled with multivariate chemometric analysis, provides a authentication tool for differentiating botanical species. Unlike chromatographic techniques, which can be manipulated by introducing synthetic analogs, NMR-based authentication relies on the holistic metabolite spectrum, making it more resistant to adulteration as it also can differentiate synthetic ingredients85. The authentication of commercial acerola is particularly significant due to its high economic value and susceptibility to adulteration with cherry derivatives. The hierarchical clustering of metabolites indicates that while M. glabra exhibits some spectral resemblance to Prunus spp., the spectra are considerably different as M. emarginata remains chemically distinct. By integrating metabolite-specific peak ratios, particularly malic acid and ascorbic acid content, a more rigorous authentication framework can be established. This approach of provides both a species ingredient identification tools while providing verification of specific bioactive metabolites that are of value to health minded consumers. The elucidation of specific bioactive metabolites is particularly valuable for product claims and specific ingredients on product labels.

Conclusion

This study provides two novel methods for the quality assurance of acerola species procured in the industry supply chain. Previously, there were no published methods for the authentication of acerola species used on commercial products. The DNA methods developed in this study have several limitations for berry extracts due to the lack of high quality DNA. These DNA methods may be cost prohibitive if the goal is to detect species adulteration from other taxa because multiple species test would be required for each potential adulterant. NMR fingerprinting developed in this study can be used for berry extracts and has the benefit of authenticating acerola species ingredients whilst detecting any adulterants in a single analysis. The resulting NMR spectra also provide quantitative estimates of bioactive phytochemicals negating the need for further analytical chemistry methods. However, there is limited adoption of NMR methods in the quality control of botanical ingredients, which poses a financial barrier to broad use of these methods. Further research is needed to develop more NMR fingerprinting methods for other botanical species ingredients. This study highlights the potential application of NMR fingerprinting as a critical quality control measure in the natural health product and food industry.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Laurindo, L. F. et al. Health benefits of acerola (Malpighia spp) and its by-products: A comprehensive review of nutrient-rich composition, pharmacological potential, and industrial applications. Food Biosci.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fbio.2024.105422 (2024).

Uma Maheswari, M., Arumugam, T. & Lincy Sona, C. Fruits and vegetables as superfoods: Scope and demand. Pharma Innov. J.10, 119–129 (2021).

Li, D. Z. et al. Comparative analysis of a large dataset indicates that internal transcribed spacer (ITS) should be incorporated into the core barcode for seed plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.108, 19641–19646 (2011).

FMI. Processed Superfruit Market Outlook from 2025 to 2035. (2025). https://www.futuremarketinsights.com/reports/processed-superfruits-market (2025).

Fernández-Ríos, A. et al. A critical review of superfoods from a holistic nutritional and environmental approach. J. Clean. Prod. Vol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.134491 (2022). 379 Preprint at.

Prakash, A. & Baskaran, R. Acerola, an untapped functional superfruit: A review on latest frontiers. J. Food Sci. Technol.55, 3373–3384. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13197-018-3309-5 (2018).

Mezadri, T., Villaño, D., Fernández-Pachón, M. S., García-Parrilla, M. C. & Troncoso, A. M. Antioxidant compounds and antioxidant activity in acerola (Malpighia emarginata DC.) fruits and derivatives. J. Food Compos. Anal. 21, 282–290 (2008).

Righetto, A. M., Netto, F. M. & Carraro, F. Chemical composition and antioxidant activity of juices from mature and immature acerola (Malpighia emarginata DC). Food Sci. Technol. Int.11, 315–321 (2005).

McGuffin, M., Tucker, A. & L., A. Y. J. T. K. Herbs of Commerce (American Herbal Products Assocation, 2000).

Duke, J. A. CRC Handbook of Alternative Cash Crops (CRC, 1993).

Rezende, Y. R. R. S., Nogueira, J. P. & Narain, N. Comparison and optimization of conventional and ultrasound assisted extraction for bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity from agro-industrial acerola (Malpighia emarginata DC) residue. LWT85, 158–169 (2017).

De Aparecida, S. et al. Antioxidant activity, ascorbic acid and total phenol of exotic fruits occurring in Brazil. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 60, 439–448 (2009).

Singh, D. R. R. West Indian Cherry ñ A lesser known fruit for nutritional security. Natural Product Radiance. 5(5), 366–368 (2006).

Belwal, T. et al. Phytopharmacology of acerola (Malpighia spp.) and its potential as functional food. Trends Food Sci. Technol.74, 99–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2018.01.014 (2018).

Paz, M. et al. Brazilian fruit pulps as functional foods and additives: Evaluation of bioactive compounds. Food Chem.172, 462–468 (2015).

do Rufino, M. Acerola and cashew Apple as sources of antioxidants and dietary fibre. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 45, 2227–2233 (2010).

Motohashi, N. et al. Biological activity of Barbados cherry (Acerola fruits, fruit of Malpighia emarginata DC) extracts and fractions. Phytother. Res.18, 212–223. https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.1426 (2004).

Leffa, D. D. et al. Corrective effects of acerola (Malpighia emarginata DC.) juice intake on biochemical and genotoxical parameters in mice fed on a high-fat diet. Mutat. Res. - Fundamental Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 770, 144–152 (2014).

Horta, R. N. et al. Protective effects of acerola juice on genotoxicity induced by iron in vivo. Genet. Mol. Biol.39, 122–128 (2016).

Düsman, E., Almeida, I. V., Tonin, L. T. D. & Vicentini, V. E. P. In vivo antimutagenic effects of the Barbados Cherry fruit (Malpighia glabra linnaeus) in a chromosomal aberration assay. Genetics Mol. Research 15(4), (2016). https://doi.org/10.4238/gmr15049036

Da Silva Nunes, R. et al. Genotoxic and antigenotoxic activity of acerola (Malpighia glabra L.) extract in relation to the geographic origin. Phytother. Res.27, 1495–1501 (2013).

Düsman, E. et al. Radioprotective effect of the Barbados Cherry (Malpighia glabra L.) against radiopharmaceutical Iodine-131 in Wistar rats in vivo. BMC Complement Altern Med. 14, 41 (2014). http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6882/14/41

da Silva Nunes, R. et al. Antigenotoxicity and antioxidant activity of acerola fruit (Malpighia glabra L.) at two stages of ripeness. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr.66, 129–135 (2011).

Hanamura, T., Mayama, C., Aoki, H., Hirayama, Y. & Shimizu, M. Antihyperglycemic effect of polyphenols from acerola (Malpighia emarginata DC.) fruit. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem.70, 1813–1820 (2006).

El-Hawary, S. S., El-Fitiany, R. A., Mousa, O. M., Salama, A. A. A. & El gedaily, R. A. Metabolic profiling and in vivo hepatoprotective activity of Malpighia glabra L. leaves. J. Food Biochem. 45(2), e13588. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfbc.13588 (2021).

Costa, A. et al. Clinical, biometric and ultrasound assessment of the effects of daily use of a nutraceutical composed of lycopene, acerola extract, grape seed extract and biomarine complex in photoaged human skin. Bras. Dermatol. 87, 52–61 (2012).

Delva, L. & Goodrich-Schneider, R. Antioxidant activity and antimicrobial properties of phenolic extracts from acerola (Malpighia emarginata DC) fruit. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol.48, 1048–1056 (2013).

de Miskinis, A. S., Nascimento, R. & Colussi, R. L. Á. Bioactive compounds from acerola pomace: A review. Food Chemistry vol. 404 Preprint at (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.134613

Vilvert, J. C., de Freitas, S. T., Veloso, C. M. & Amaral, C. L. F. Genetic diversity on acerola quality: A systematic review. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol.https://doi.org/10.1590/1678-4324-2024220490 (2024).

de Assis, S. A., Lima, D. C. & de Faria Oliveira, O. M. M. Activity of pectinmethylesterase, pectin content and vitamin C in acerola fruit at various stages of fruit development. Food Chem.74, 133–137 (2001).

dos Santos, C. P. et al. Transcriptome analysis of acerola fruit ripening: Insights into ascorbate, ethylene, respiration, and softening metabolisms. Plant. Mol. Biol.101, 269–296 (2019).

Fernandes, F. A. N., Santos, V. O., Gomes, W. F. & Rodrigues, S. Application of high-intensity ultrasound on acerola (Malpighia emarginata) juice supplemented with fructooligosaccharides and its effects on vitamins, phenolics, carotenoids, and antioxidant capacity. Processeshttps://doi.org/10.3390/pr11082243 (2023).

Assis, S. A., De, Fernandes, F. P., Martins, A. B. G., Oliveira, O. M. M. D. F. & Acerola Importance, culture conditions, production and biochemical aspects. Fruits vol. 63 93–101 Preprint at (2008). https://doi.org/10.1051/fruits:2007051

Ragupathy, S. et al. Exploring DNA quantity and quality from raw materials to botanical extracts. Heliyonhttps://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e01935 (2019).

Yip, P. Y., Chau, C. F., Mak, C. Y. & Kwan, H. S. DNA methods for identification of Chinese medicinal materials. Chin. Med.https://doi.org/10.1186/1749-8546-2-9 (2007).

Newmaster, S., Ragupathy, S. & Kress, W. J. Authentication of Medicinal Plant Components in North America’s NHP Industry Using Molecular Diagnostic Tools. in Medicinal and Aromatic Plants of North America (ed. Máthé, Á.) 325–339Springer International Publishing, Cham, (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-44930-8_13

Kesanakurti, P. et al. Development of hydrolysis probe-based qPCR assays for Panax ginseng and Panax quinquefolius for detection of adulteration in ginseng herbal products. Foods. 10, 2705. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10112705 (2021).

Yu, J. et al. Progress in the use of DNA barcodes in the identification and classification of medicinal plants. Ecotoxicol Environ. Saf 208, 111691 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.111691

Raclariu-Manolică, A. C. & de Boer, H. J. Chapter 8 - DNA barcoding and metabarcoding for quality control of botanicals and derived herbal products. in Evidence-Based Validation of Herbal Medicine (Second Edition) (ed. Mukherjee, P. K.) 223–238 (Elsevier, 2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-85542-6.00004-4

Travadi, T. et al. Advancing Herbal Product Authentication: A Comprehensive Review Of DNA-Based Approach For Quality Control And Safety Assurance. Educational Adm. Theory Practices doi:https://doi.org/10.53555/kuey.v30i6(s).5308. (2024).

Lanubile, A., Stagnati, L., Marocco, A. & Busconi, M. DNA-based techniques to check quality and authenticity of food, feed and medicinal products of plant origin: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2024.104568 (2024).

Muyumba, N. W., Mutombo, S. C., Sheridan, H., Nachtergael, A. & Duez, P. Quality control of herbal drugs and preparations: The methods of analysis, their relevance and applications. Talanta Open. 4, 100070. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.talo.2021.100070 (2021).

Ichim, M. C. & Booker, A. Chemical authentication of botanical ingredients: A review of commercial herbal products. Front. Pharmacol.https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2021.666850 (2021).

Abraham, E. J. & Kellogg, J. J. Chemometric-guided approaches for profiling and authenticating botanical materials. Front. Nutr.https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2021.780228 (2021).

Klein-Junior, L. C. et al. Quality control of herbal medicines: From traditional techniques to state-of-the-art approaches. Planta Med.87, 964–988. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1529-8339 (2021).

Salo, H. M. et al. Authentication of berries and berry-based food products. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 20, 5197–5225 (2021).

García-Pérez, P., Becchi, P. P., Zhang, L., Rocchetti, G. & Lucini, L. Metabolomics and chemometrics: The next-generation analytical toolkit for the evaluation of food quality and authenticity. Trends Food Sci. Technol.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2024.104481 (2024).

Ichim, M. C., Scotti, F. & Booker, A. Quality evaluation of commercial herbal products using chemical methods. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr.64, 4219–4239. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2022.2140120 (2024).

Urumarudappa, S. K. J. et al. DNA barcoding and NMR spectroscopy-based assessment of species adulteration in the raw herbal trade of Saraca asoca (Roxb.) willd, an important medicinal plant. Int. J. Legal Med.130, 1457–1470 (2016).

Kesanakurti, P., Thirugnanasambandam, A., Ragupathy, S. & Newmaster, S. G. Genome skimming and NMR chemical fingerprinting provide quality assurance biotechnology to validate sarsaparilla identity and purity. Sci. Rep. 10, 19192. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-76073-7 (2020).

Shirahata, T. et al. Metabolic fingerprinting for discrimination of DNA-authenticated atractylodes plants using 1H NMR spectroscopy. J. Nat. Med.75, 475–488 (2021).

Alberts, P. S. F. & Meyer, J. J. M. Integrating chemotaxonomic-based metabolomics data with DNA barcoding for plant identification: A case study on south-east African Erythroxylaceae species. South. Afr. J. Bot. 146, 174–186 (2022).

Ragupathy, S., Thirugnanasambandam, A., Vinayagam, V. & Newmaster, S. G. Nuclear magnetic resonance fingerprints and mini DNA markers for the authentication of cinnamon species ingredients used in food and natural health products. Plantshttps://doi.org/10.3390/plants13060841 (2024).

Ragupathy, S. et al. Flower species ingredient verification using orthogonal molecular methods. Foods. 13(12), 1862.https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13121862 (2024).

Wang, X. et al. Fruit and vegetable consumption and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer: Systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMJ. 349, 5472. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g4490 (2014).

Martinez-Farina, C. F. et al. Chemical barcoding: A nuclear-magnetic-resonance-based approach to ensure the quality and safety of natural ingredients. J. Agric. Food Chem.67, 7765–7774 (2019).

Grazina, L., Amaral, J. S. & Mafra, I. Botanical origin authentication of dietary supplements by DNA-based approaches. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf.19, 1080–1109. https://doi.org/10.1111/1541-4337.12551 (2020).

Raclariu, A. C., Heinrich, M., Ichim, M. C. & de Boer, H. Benefits and limitations of DNA barcoding and metabarcoding in herbal product authentication. Phytochem. Anal.29, 123–128. https://doi.org/10.1002/pca.2732 (2018).

Sarwat, M. & Yamdagni, M. M. DNA barcoding, microarrays and next generation sequencing: Recent tools for genetic diversity estimation and authentication of medicinal plants. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol.36, 191–203. https://doi.org/10.3109/07388551.2014.947563 (2016).

Mahima, K. et al. Advancements and future prospective of DNA barcodes in the herbal drug industry. Front. Pharmacol.https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.947512 (2022).

Osman, A. et al. Quality consistency of herbal products: chemical evaluation. In Progress in the Chemistry of Organic Natural Products 122: Botanical Dietary Supplements and Herbal Medicines (eds Kinghorn, A. D. et al.) 163–219 (Springer Nature Switzerland, 2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-26768-0_2.

Bharti, S. K. & Roy, R. Quantitative 1H NMR spectroscopy. TrAC - Trends in Analytical Chemistry35, 5–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trac.2012.02.007 (2012).

Sobolev, A. P., Ingallina, C., Spano, M., Di Matteo, G. & Mannina, L. NMR-based approaches in the study of foods. Moleculeshttps://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27227906 (2022).

Esslinger, S., Riedl, J. & Fauhl-Hassek, C. Potential and limitations of non-targeted fingerprinting for authentication of food in official control. Food Res. Int. 60, 189–204 (2014).

Lolli, V. & Caligiani, A. How nuclear magnetic resonance contributes to food authentication: Current trends and perspectives. Curr. Opin. Food Sci.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cofs.2024.101200 (2024).

Wishart, D. S. Metabolomics: Applications to food science and nutrition research. Trends Food Sci. Technol.19, 482–493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2008.03.003 (2008).

Spiteri, M. et al. Fast and global authenticity screening of honey using 1H-NMR profiling. Food Chem.189, 60–66 (2015).

Giraudeau, P. Quantitative NMR spectroscopy of complex mixtures. Chem. Commun. 59, 6627–6642 (2023).

Holmes, E., Tang, H., Wang, Y. & Seger, C. The Assessment of Plant Metabolite Profiles by NMR-Based Methodologies. (2006). https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2006-946682

Mahmud, I., Chowdhury, K. & Boroujerdi, A. PTC&B Tissue-Specific Metabolic Profile Study of Moringa Oleifera L. Using Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. Plant Tissue Cult. & Biotech vol. 24 (2014).

Rosario, L. H. et al. DNA barcoding of the Solanaceae family in Puerto Rico including endangered and endemic species. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci.144, 363–374 (2019).

Sayed, H. A., Mostafa, S., Haggag, I. M. & Hassan, N. A. DNA barcoding of Prunus species collection conserved in the National gene bank of Egypt. Mol. Biotechnol.65, 410–418 (2023).

Kress, W. J., Erickson, D. L. A. & Two-Locus Global DNA barcode for land plants: the coding RbcL gene complements the Non-Coding trnH-psbA spacer region. PLoS One 2(6), e508 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0000508

Baldwin, B. G. et al. The its region of nuclear ribosomal DNA: A valuable source of evidence on angiosperm phylogeny. Ann. Mo. Bot. Gard.82247. (1995).

Kress, W. J., Wurdack, K. J., Zimmer, E. A., Weigt, L. A. & Janzen, D. H. Use of DNA Barcodes to Identify Flowering Plants. (2005). http://www.pnas.org.10.1073pnas.0503123102

Cheng, T. et al. Barcoding the kingdom plantae: New PCR primers for ITS regions of plants with improved universality and specificity. Mol. Ecol. Resour.16, 138–149 (2016).

Yao, H. et al. Use of ITS2 region as the universal DNA barcode for plants and animals. PLoS One. 5(10), e13102.https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0013102 (2010).

Kress, W. J. Plant DNA barcodes: Applications today and in the future. J. Syst. Evol.55, 291–307. https://doi.org/10.1111/jse.12254 (2017).

Antil, S. et al. DNA barcoding, an effective tool for species identification: A review. Mol. Biol. Rep.50, 761–775. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-022-08015-7 (2023).

Fazekas, A. J., Kuzmina, M. L., Newmaster, S. G. & Hollingsworth, P. M. DNA barcoding methods for land plants. in 223–252 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-61779-591-6_11

Thompson, J. D., Higgins, D. G. & Gibson, T. J. CLUSTAL w: Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res.22, 4673–4680 (1994).

Tamura, K., Stecher, G. & Kumar, S. MEGA11: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 3022–3027 (2021).

Beckonert, O. et al. Metabolic profiling, metabolomic and metabonomic procedures for NMR spectroscopy of urine, plasma, serum and tissue extracts. Nat. Protoc.2, 2692–2703 (2007).

Nicholson, J. K., Foxall, P. J. D., Spraul, M., Farrant, R. D. & Lindon J. C. 750 MHz 1H and 1H-13 C NMR Spectroscopy of Human Blood Plasma. Anal Chem 67, 793–811 (1995).

Emwas, A. H. M. The strengths and weaknesses of NMR spectroscopy and mass spectrometry with particular focus on metabolomics research. in 161–193 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-2377-9_13

Lê, S., Josse, J. & Husson, F. FactoMineR: an R package for multivariate analysis. J Stat. Softw 25, 1–18. (2008). https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v025.i01

Bourafai-Aziez, A. et al. Development, validation, and use of 1H-NMR spectroscopy for evaluating the quality of Acerola-based food supplements and quantifying ascorbic acid. Molecules, 27(17), 5614. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27175614 (2022).

Smillie, T. J. & Khan, I. A. A comprehensive approach to identifying and authenticating botanical products. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther.87, 175–186. https://doi.org/10.1038/clpt.2009.287 (2010).

Mukherjee, P. K., Bahadur, S., Chaudhary, S. K., Kar, A. & Mukherjee, K. Chapter 1 - Quality Related Safety Issue-Evidence-Based Validation of Herbal Medicine Farm To Pharmain 1–28 (Elsevier Inc, 2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-800874-4.00001-5

Govindaraghavan, S. & Sucher, N. J. Quality assessment of medicinal herbs and their extracts: Criteria and prerequisites for consistent safety and efficacy of herbal medicines. Epilepsy Behav.52, 363–371 (2015).

Dubey, N. K., Kumar, R. & Tripathi, P. Global promotion of herbal medicine: india’s opportunity. Curr Sci 86, 37–41 (2004).

de Medeiros, F. G. M., Pereira, G. B. C., Pedrini, M. R. S., Hoskin, R. T. & Nunes, A. O. Evaluation of the environmental performance of the production of polyphenol-rich fruit powders: A case study on acerola. J Food Eng 372, (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2024.112010

Gomes, B. T. et al. Acerola byproducts microencapsulated by spray and freeze-drying: the effect of carrier agent and drying method on the production of bioactive powder. Int. J. Food Eng. 20, 347–356 (2024).

Fonseca, M. T. et al. Improving the stability of spray-dried probiotic acerola juice: A study on hydrocolloids’ efficacy and process variables. Food Bioprod. Process.147, 209–218 (2024).

Coelho, B. E. S. et al. Production and characterization of powdered acerola juice obtained by atomization. Acta Scientiarum - Technology 47, 1–14 (2025).

Walsh, K. B. & Ragupathy, S. Mycorrhizal colonisation of three hybrid papayas (Carica papaya) under mulched and bare ground conditions. Aust. J. Exp. Agric.4781. (2007).

Dubouzet, J. G. & Shinoda, K. Phylogenetic analysis of the internal transcribed spacer region of Japanese Lilium species. Theor. Appl. Genet.98, 954–960 (1999).

Faller, A. C. et al. DNA quality and quantity analysis of camellia sinensis through processing from fresh leaves to a green tea extract. J. AOAC Int.102, 1798–1807 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We thank Natural health product research alliance (NHPRA), University of Guelph for supporting this study. We would like to thank the Genomics facility, University of Guelph for their help in carrying out experiments in their lab and also for their timely help and assistance whenever needed. Thomas Henry is greatly acknowledged for his help in the wet lab.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sub.R. and S.G.N conceived the project and experiments; Sub.R and R.Sne. carried out the DNA molecular work and analysis; V.V., R.Sne. and A.T. carried out the NMR metabolite lab work and analysis; Sub.R. led the manuscript writing, and all other authors contributed to writing, editing, reading and accepting the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Funding

Funding for this research was provided by the Natural Health Product Research Alliance, University of Guelph, grant number 053312.

Additional information

The authors confirm that Dr Ragupathy is the trained taxonomist who identified all plants. All the vouchers are recorded in Table S1, and their metadata are listed in Table S3. The specimens were deposited at the Natural Health Products Research Alliance, University of Guelph. The plants used in this study are common, commercially available species that do not require any permits/permissions/licenses.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ragupathy, S., Thirugnanasambandam, A., Vinayagam, V. et al. Development of molecular diagnostic methods to distinguish acerola species for quality assurance of food, dietary supplements and natural health products. Sci Rep 15, 28361 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12408-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12408-6