Abstract

Various studies have confirmed the benefits of total neoadjuvant therapy (TNT) for locally advanced rectal cancer (LARC). Nevertheless, preoperative intensive treatment and a long waiting period can lead to significant side effects. This may result in surgical difficulties and a higher complication rate. The individualized modified TNT (mTNT) model might lessen the side effects without influencing the curative effect. The clinical data of LARC with short-course neoadjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy in the same attending group of colorectal surgery at Fujian Cancer Hospital were retrospectively examined from January 2017 to October 2023. An analysis was carried out on aspects such as the adverse reaction of chemoradiotherapy, postoperative complications, pathological withdrawal, and long-term outcomes of the data. 62 cases were enrolled, including 16 cases of induction chemotherapy mode (IC group), 20 cases of consolidation chemotherapy mode (CC group), and 26 cases of induction + consolidation chemotherapy sandwich mode (IC + CC group). In all three groups, the neoadjuvant therapy compliance rate reached 100%. No grade 4—5 toxicity was found, and the perioperative complication rate of 12.90% was within an acceptable range, including major complications, 4 cases of anastomotic leakage and one case of abdominal bleeding. Delayed complications including ileus and rectovaginal fistula occured in 5 patients, all of whom received consolidation chemotherapy and had BMI less than 21. There was a total pathological complete remission (pCR) rate of 24.19%, including IC group 18.75%, CC group 25.00%, and IC + CC group 26.92%. The downstaging rate of IC + CC group was significantly higher than that of IC group and CC group (P = 0.037). In comparison with those in the CC or IC + CC group, patients in the IC group, had lower Locoregional relapse-free survival (LRFS) rate (81.3%vs.82.5% and 92.9%, respectively, P = 0.292), and higher Distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS) rate (93.8% vs.73.1% and 82.4%, respectively, P = 0.365), however, these variances were not of significance. The initial outcomes of the individualized modified TNT model are promising. Sequencing adjusted according to the disease risk upon presentation might be the best way to balance local and distant disease control and treatment toxicity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) ranks as the third most prevalent cancer worldwide and the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality1,2,3. For locally advanced rectal cancer (LARC), the current standard of care consists of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (nCRT) followed by total mesorectal excision (TME) and adjuvant chemotherapy (ACT)4. Although preoperative concurrent chemoradiotherapy significantly lowers local recurrence rates, its effect on distant metastasis control remains limited. Furthermore, ACT has not demonstrated substantial improvements in disease-free survival (DFS) or overall survival (OS), while poor patient compliance and tolerance frequently lead to dose reductions, undermining treatment efficacy5,6. To overcome these challenges, total neoadjuvant therapy (TNT) was developed, which involves moving all the postoperative ACT either before or after nCRT prior to radical surgery7. Intensified preoperative chemotherapy has been associated with enhanced treatment response and prolonged survival8. A Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center study demonstrated that incorporating the FOLFOX regimen (oxaliplatin + fluorouracil + leucovorin) before nCRT yielded a pathologic or clinical complete response (pCR/cCR) in 36% of patients9. By 2019, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines had formally integrated TNT into their treatment recommendations for LARC.

The optimal radiotherapy regimen within total neoadjuvant therapy (TNT)—short-course radiotherapy (SCRT) versus long-course radiotherapy (LCRT)—remains controversial. SCRT presents distinct advantages, including fewer treatment sessions, reduced costs, and earlier initiation of systemic chemotherapy. Multiple randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and observational studies (e.g., the Polish II and RAPIDO trials) have validated its efficacy in LARC when combined with either consolidation or induction chemotherapy10,11. However, critical uncertainties persist. The optimal sequencing of chemotherapy and radiotherapy remains unclear, and whether treatment strategies should be tailored based on patient risk stratification is still uncertain. Although TNT intensifies systemic chemotherapy, it also prolongs the interval between neoadjuvant therapy and surgery, which may increase surgical complexity and complication risks12. Another unresolved issue is whether postoperative chemotherapy remains necessary for patients who achieve pCR after nCRT13,14. These considerations suggest that TNT could potentially lead to overtreatment in certain patient subgroups.

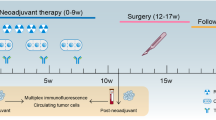

To address these challenges, researchers have proposed a modified TNT (mTNT) approach for individualized preoperative neoadjuvant therapy. Unlike conventional TNT, this strategy administers only a portion (rather than the full course) of planned ACT before surgery, thereby shortening neoadjuvant treatment duration and reducing the surgical waiting period. By optimizing tumor downsizing while minimizing overtreatment risks, this approach aims to ensure R0 resection and improve therapeutic precision15. Since 2017, our institution has adopted an individualized mTNT approach (SCRT + oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy) for LARC patients. This study aims to evaluate its effectiveness, safety, and mid-term oncological outcomes. Furthermore, we explore different neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NCT) strategies, such as induction chemotherapy followed by SCRT, consolidation chemotherapy after SCRT, or induction chemotherapy followed by SCRT and then consolidation chemotherapy (sandwich TNT), to determine the optimal timing of NCT and SCRT for LARC patients.

Materials and methods

Patients

A digital medical record management system was utilized to retrieve the clinical data of LARC patients who received neoadjuvant therapy and TME from the Department of Colorectal Surgery of Fujian Tumor Hospital by the same medical team, covering the period from January 2017 to October 2023. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Age ranging from 18 to 75 years. (2) Confirmed rectal adenocarcinoma with the lower margin of the tumor located ≤ 10 cm from the anal verge, or located below the peritoneal reentry; (3) Clinical stage: cT 3b-c, 4a or N + M0 tumor (via MRI diagnosis or intrarectal ultrasonography, tumor infiltration of muscularis propria depth: T 3b 5-10 mm, T 3c > 10 mm); (4)Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, ECOG score 0 ~ 1 or Karnofsky score ≥ 70, no serious heart, brain, lung and other basic diseases, be able to tolerate radiotherapy, chemotherapy and surgery; (5)The medical record data is detailed, the imaging data and the postoperative pathology data are complete. Exclusion criteria:(1) Distant metastasis (M1); (2) Clinical sage: T4bM0 case; (3) Familial adenomatous polyposis, simultaneous multigenous carcinoma of the large intestine, metachronous multigenous carcinoma of large intestine; (4) Neuroendocrine tumor, inherited tumor or inflammatory bowel disease; (5) Complicated with other uncured malignant tumors (≤ 3 years after cure).

Treatment

Regional lymph nodes, elective pelvic lymph nodes, and the entire mesorectum with adequate margins were included in the radiotherapy target areas, which were identified by experienced attending physicians. All patients were performed by the same attending group of colorectal surgeons with more than 15 years of experience in laparoscopic surgery. The SCRT-mTNT consisted of five successive fractions of 2500 cGy and systemic chemotherapy. It was categorized into three mode groups as per the sequence. Group 1 named induction chemotherapy group (IC group): mFOLFOX6 induction chemotherapy 3 ~ 6 cycles → SCRT (DT 2500 cGy/5 F) → laparoscopic TME → mFOLFOX6 3 ~ 6 cycles ACT. Group 2 named consolidation chemotherapy group (CC group): SCRT (DT 2500 cGy/5 F) → mFOLFOX6 consolidation chemotherapy 3 ~ 6 cycles → laparoscopic TME → mFOLFOX6 3 ~ 6 cycles ACT. Group 3 named induction and consolidation chemotherapy group (IC + CC group): mFOLFOX6 induction chemotherapy 2 cycles → SCRT (DT 2500 cGy/5 F) → mFOLFOX6 consolidation chemotherapy 2 ~ 4 cycles → laparoscopic TME → mFOLFOX6 3 ~ 6 cycles ACT. The total course of chemotherapy in mTNT was at least 8 cycles for the mFOLFOX6 regimen or an equivalent regimen containing Capox or capecitabine regimen. Patients enrolled should complete at least 4 cycles of neoadjuvant mFOLFOX6 chemotherapy or an equivalent regimen containing Capox or a capecitabine regimen. mFOLFOX6 regimen: Oxaliplatin 85 mg/m2 ivgtt d 1 + left calcium folinate 200 mg/m2 ivgtt d 1 + 5-FU 400 mg/m2 ivgtt d 1 + 5-FU 2400 mg/m2 CIV for 46 ~ 48 h, one cycle every two weeks. Capox regimen: Oxaliplatin 135 mg/m2 ivgtt d 1 + Capecitabine 2000 mg/m2 p.o d 1–14, one cycle every three weeks.

Observation index and evaluation of curative effect

-

1.

Clinical data include basic information such as age, gender, body mass index, the distance between the tumor and the anal margin, ECOG score, the differentiation of the tumor, TNM stage, extramural vascular invasion (EMVI), etc.

-

2.

The radiotherapy and chemotherapy may lead to some adverse reactions, which are graded and evaluated based on the Common Terminology Criterion Adverse Events (CTCAE) Version 5.0.

-

3.

Perioperative safety: The intraoperative conditions and complications such as operation-related infection, anastomotic leakage, bleeding, and cardiorespiratory complications within 30 days after operation were compared between the three groups.

-

4.

Clinical assessment was carried out in accordance with RECIST 1.1. The cCR is regarded as no remaining lesions shown by multiple clinical and imaging techniques (such as anal digital examination, colonoscopy, ultrasonic endoscopy, CT, MRI, etc.). The NCCN guidelines recommend Ryan R’s modified Tumor Regression Grading (TRG) system for evaluating tumor treatment response: TRG 0 means complete retraction, TRG 1 indicates near complete retraction, and TRG 2 represents partial retraction. TRG 3 means poor or no retraction at all. All patients had their postoperative pathology restaged. Pathology—confirmed complete remission (ypT 0) with no remaining tumor cells after nCRT and surgery was defined as pCR, regardless of whether regional lymph nodes were involved or not.

-

5.

As per the NCCN guidelines, postoperative follow-up for patients involves rechecking. In the first 2 years, rechecks should be made every 3 months. From 2 to 5 years, every 6 months is recommended, and after 5 years, an annual recheck is advisable. These rechecks include digital rectal examination, tumor markers, enhanced CT of chest, abdomen, and pelvis, MRI of rectum and pelvis, and colonoscopy. The follow-up details were gathered either by looking into the patient’s outpatient re-examination records or via telephone follow-up. The most recent follow-up took place on October 1, 2023.

Statistical analysis

The data of continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation. and the Mann–Whitney U test or analysis of variance (ANOVA) was utilized for comparison. Categorical variables data, etc., clinical efficacy, safety, and tolerability outcomes, were described in relevant percentages, and compared using Pearson’s chis-quare test or Fisher’s exact test. The Kaplan–Meier method was employed for survival analysis, and the Cox-Mantel log-rank test was used for comparison between groups. P < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. Statistical analyses were carried out with SPSS 24.0.

Results

The characteristics of patients

Patient characteristics are presented in Table 1. A total of 62 patients were enrolled in this study, comprising 38 males and 24 females. Among them, 16 patients (25.81%) were in the IC group, 20 cases (32.26%) were in the CC group, and 26 patients (41.94%) were in the IC + CC group. All patients were discussed and approved by a multi-disciplinary team (MDT) of CRC specialists before treatment. There was no significant difference in baseline data such as age, sex, body mass index (BMI), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, tumor distance from anal verge, clinical TNM stage, tumor differentiation, and extramural vascular invasion (EMVI) (P > 0.05). Nevertheless, 50% of patients in the IC group had clinical T4 stage rectal cancer, compared to 10% in the CC group and 34.6% in the IC + CC group (P < 0.05).

Compliance and acute toxicity

Table 2 summarizes the compliance with radiotherapy and chemotherapy, as well as the associated toxicities. All patients completed the planned full dose radiotherapy. 60 patients (96.77%) received at least 3 cycles of neoadjuvant mFOLFOX6 chemotherapy. In the IC and CC group, one patient each discontinued oxaliplatin due to allergic reactions, and had only received 3 and 4 cycles of the mFOLFOX 6 regimen, respectively, before switching to oral capecitabine for subsequent chemotherapy. To reduce hospitalization time, some patients transitioned to the Capox regimen during the later stages of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Overall, 54 patients (87.10%) completed the full course of chemotherapy. In the CC and IC + CC groups, two patients in each group gave up postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy because of severe digestive tract reactions. For patients who achieved pCR, oral capecitabine was used for maintenance therapy during the adjuvant phase.

As shown in Table 2, patients demonstrated good tolerance to the SCRT-mTNT regimen, with only mild adverse reactions and no grade 4–5 toxicities observed. No significant differences were found among the groups regarding the number of neoadjuvant chemotherapy cycles, completion of adjuvant chemotherapy, or the incidence of radiotherapy- and chemotherapy-related toxicities (P > 0.05). Most patients completed four to six cycles of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Gastrointestinal toxicity, hematological toxicity, liver function impairment, peripheral neurotoxicity, and skin toxicity were predominantly grade 0–1, with a low incidence of severe (grade 2–3) toxicities.

Operation and postoperative complications

Table 3 summarizes the surgical procedures and postoperative complications of the patients. All 62 patients underwent TME. The median interval between radiotherapy and surgery was as follows: 7 days in the IC group, 87 days (range: 58 to 127 days) in the CC group, and 72 days (ranging from 45 to 108 days) in the IC + CC group. All patients were performed by laparoscopy with R0 resection. 56 patients (90.32%) underwent Dixon and prophylactic terminal ileostomy. The proportion of abdominal perineal resection (APR) in the CC group was significantly higher than in the IC and IC + CC groups (P < 0.05).

The overall incidence of major perioperative complications (within 30 days) was 12.90% in 62 patients, including 4 cases of anastomotic leakage (1 case in the IC group, 2 in the CC group and 1 in the IC + CC group), and 2 cases of simple abdominal infection (1 in the CC group and 1 in the IC + CC group). All 6 patients were treated with continuous irrigation and anti-inflammatory therapy, which resulted in improvement. Additionally, 1 patient in the IC + CC group with anastomotic bleeding was successfully treated with colonoscopy hemostasis. One patient in the CC group with intraperitoneal hemorrhage was treated by secondary exploration laparotomy for hemostasis. Minor perioperative complications included pulmonary infection, lymphatic leakage, ileus, urinary retention, incision Infection, and deep venous thrombosis of the lower extremity. No serious adverse events such as death or secondary heart, brain, and lung injury occurred within 30 days after the operation. There were no statistically significant differences between the three groups in terms of operative time, blood loss, and postoperative hospital stay, or other complication rates (P > 0.05).

Three patients (two in the CC group and one in the IC + CC group) had at least one ileus from one month to one year after operation. All the three patients had ileus during perioperative period. The two cases in CC group could not perform ileostomy closure, and one of the patients died of ileus complicated with septic shock one year after operation. Two female patients developed delayed rectovaginal fistula about half a year after operation. One case was in the CC group (6 cycles of consolidation chemotherapy), and the other case was in the IC + CC group (2 cycles of induction chemotherapy + 4 cycles of consolidation chemotherapy). All the 5 patients with delayed complications were treated with consolidation chemotherapy and had BMI less than 21.

Pathology and tumor response

Table 3 also summarizes the postoperative pathological and tumor response findings. All patients who received TME treatment showed negative distal and circumferential margins. No statistically significant differences were observed between the three groups regarding pathological stage, nerve invasion, vascular tumor thrombus, and TRG grade (P > 0.05). Overall, 96.77% of patients achieved a good pathological response (TRG 0–2). However, the IC group had a higher proportion of TRG 3, indicating a poorer response compared to the CC group and the IC + CC group. This also reflects a significant difference in the downstaging rate, with the IC + CC group showing a notably higher rate than the IC and CC groups, and the difference was statistically significant (P = 0.037). The overall rate of pCR was 24.19%, with 18.75% in the IC group, 25.00% in the CC group, and 26.92% in the IC + CC group.

Follow-up

The median follow-up duration was 23.5 months (range: 5.5 to 73 months). The 3-year OS, DFS, locoregional relapse-free survival (LRFS), and distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS) rates for all patients were 89.1%, 79.0%, 86.1%, and 82.4%, respectively.

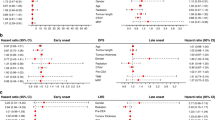

During the follow-up period, 5 patients died. Among them, 2 deaths in the CC group and 1 in the IC + CC group were attributed to liver metastases. One patient in the IC group died from a sudden cerebral hemorrhage one week after ileostomy reversal surgery, and 1 patient in the CC group succumbed to infectious shock caused by multiple intestinal obstructions secondary to abdominal fibrosis one year postoperatively. OS outcomes for the three groups are presented in Fig. 1A (P = 0.455).

Kaplan–Meier curves showing OS, DFS, LRFS, and DMFS rates comparing different groups (IC, CC, and IC + CC). OS: Overall survival, DFS: Disease-free survival, LRFS: Locoregional relapse-free survival DMFS: Distant metastasis-free survival, IC: Induction chemotherapy mode, CC: Consolidation chemotherapy mode, IC + CC: Induction + consolidation chemotherapy sandwich mode.

A total of 12 patients (19.35%) experienced disease progression (3 in the IC group, 5 in the CC group, and 4 in the IC + CC group), with the corresponding DFS analysis shown in Fig. 1B (P = 0.804). After surgery, two patients in the IC group had local recurrence and their DFS time was 12 months; Liver metastasis occurred in five patients (three in CC group and two in IC + CC group), and the average DFS was 15 months; Two patients (one in CC group and the other in IC + CC group) had lung metastasis, and the average DFS was 14.5 months; One case in IC + CC group developed peritoneal metastasis with DFS of 11.5 months. Compared with the CC and IC + CC groups, patients in the IC group exhibited a lower local LRFS rate (81.3% vs. 82.5% and 92.9%, respectively; P = 0.292, Fig. 1C) and a higher DMFS rate (93.8% vs. 73.1% and 82.4%, respectively; P = 0.365, Fig. 1D). However, these differences were not statistically significant.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that the individualized mTNT approach showed favorable safety and feasibility in rectal cancer treatment, effectively reducing treatment-related adverse events while maintaining therapeutic efficacy. Although conventional TNT (preoperative chemoradiotherapy) improves pCR rates, it increases surgical complications and treatment toxicity13,16,17,18. Currently, the W&W strategy for rectal cancer has not been widely and actively accepted, and surgery is still the dominant treatment after neoadjuvant therapy in China. The mTNT strategy, through personalized adjustment of treatment sequence and intensity, minimizes overtreatment-induced toxicities and enhances patient tolerance to preoperative therapy and surgery19,20.

In our study, all three mTNT modalities (induction chemotherapy, consolidation chemotherapy, and sandwich TNT) demonstrated comparable efficacy and tolerability with high chemotherapy compliance and low incidence of severe adverse events. Compared to the 26.5% grade III-V acute toxicity rate in the STELLAR trial’s TNT arm, our study observed no grade 4–5 toxicities during neoadjuvant treatment, with only minor grade 3 events occurring during adjuvant chemotherapy. The overall pCR rate of 24.19% was comparable to STELLAR (21.8%) and RAPIDO (28%) trials11,21,22. Notably, only two local recurrences occurred within 3 years (both in the IC group), significantly lower than the 8.4% local recurrence rate in STELLAR’s TNT arm21, indicating superior local control. As neither STELLAR nor RAPIDO incorporated induction chemotherapy—focusing instead on consolidation chemotherapy with extended waiting periods—we conclude that mTNT demonstrates non-inferiority to their TNT protocols.

Postoperative complication rates were generally low across mTNT groups (12.90% overall). While the consolidation chemotherapy groups (CC: 25.00%; IC + CC: 26.92%) achieved slightly higher pCR rates than the induction group (IC: 18.75%), they showed increased surgical complications (e.g., anastomotic leakage, intraoperative bleeding) and late-term adverse effects (e.g., pelvic fibrosis, intestinal obstruction, rectovaginal fistula), potentially attributable to excessive consolidation chemotherapy post-radiation or prolonged surgery intervals23,24,25,26. This underscores the need to balance treatment intensity and waiting periods. Importantly, all delayed complications occurred in consolidation groups among patients with BMI < 21 kg/m2, suggesting lean individuals may be more susceptible to radiation-induced fibrosis. With reduced peritoneal/pelvic fat cushioning, standard 2500 cGy/5-fraction radiation may disproportionately affect such patients, increasing risks of radiation enteritis and pelvic fibrosis. Thus, neoadjuvant strategies should be tailored to body habitus, avoiding excessive chemotherapy or delayed surgery to mitigate complications.

In our study, Survival analysis revealed 3-year OS of 89.1%, comparable to STELLAR (86.5%) and RAPIDO (89.1%). Intermediate follow-up showed superior 3-year disease-free survival (DFS: 79.0%) and distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS: 82.4%) versus STELLAR’s 64.5% and 77.1%11,21,22. Disease-related treatment failure (DrTF) rate was 16.1%, significantly lower than the 23.9% reported in the RAPIDO study11,22. DFS was still mainly affected by distant metastasis, and the rate of distant metastasis at the follow—up point was 12.9% (8/62), which seems better compared to the 20% of 3—year DM rate in the RAPIDO trial11,22. Also, even if pCR rates are better with consolidation (CC, IC + CC) than induction NCT (IC), it does not seem to result in advantages for metastasis-free, OS or DFS. In contrast, the IC group and the IC + CC group had somewhat better OS and DFS compared to the CC group. However, the differences were not statistically significant (P > 0.05).

We note that the IC group had higher N + prevalence, partly because some patients (particularly those with tumors at peritoneal reflection) initially planned for neoadjuvant chemotherapy alone, required subsequent radiotherapy due to suboptimal local control after 4–5 cycles, transitioning to mTNT. Given the heterogeneity of LARC, treatment should be further individualized: induction chemotherapy may benefit high-risk distant metastasis (N +) cases; consolidation chemotherapy may suit high local recurrence risk (T4a/T3b-c); while sandwich TNT combines both advantages. Selected patients (e.g., high rectal tumors or lean individuals) may consider neoadjuvant chemotherapy alone and omit radiotherapy after thorough evaluation to reduce toxicity. Thus, mTNT optimizes conventional TNT by balancing efficacy and safety through flexible personalization.

Study limitations include: 1) Median follow-up of 23.5 months precludes definitive assessment of long-term outcomes (DFS/OS); 2) Being a single-center retrospective study with limited sample size, some subgroups had small numbers, potentially affecting statistical power and generalizability. Future large-scale prospective studies with extended follow-up are needed to validate mTNT’s long-term safety/efficacy in LARC. Additionally, personalized sequencing and intensity strategies require prospective trials to optimize LARC treatment paradigms.

Conclusions

The individualized mTNT is a safe and effective treatment approach that does not increase chemoradiation-related toxicities or postoperative complications in patients with LARC. However, further multicenter, large-scale studies are needed to determine the optimal mTNT regimen-including the most suitable patient population, the ideal sequencing of chemoradiation, the best therapeutic protocol, and the optimal interval between neoadjuvant therapy and surgery—to achieve the optimal balance between local control, distant control, and treatment-related toxicity.

Data availability

Availability of data and materials The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- TNT:

-

Total neoadjuvant therapy

- LARC:

-

Locally advanced rectal cancer

- nRT:

-

Neoadjuvant radiotherapy

- CRC:

-

Colorectal cancer

- IC:

-

Induction chemotherapy

- CC:

-

Consolidation chemotherapy

- PCR:

-

Pathological complete remission

- LRFS:

-

Locoregional relapse-free survival

- DMFS:

-

Distant metastasis-free survival

- nCRT:

-

Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy

- TME:

-

Total mesorectal excision

- ACT:

-

Adjuvant chemotherapy

- DFS:

-

Diseasefree survival

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- DrTF:

-

Disease-related treatment failure

- SCRT:

-

Short-course radiotherapy

- LCRT:

-

Long-course radiotherapy

- MRF:

-

Mesorectal invasion

- EMVI:

-

Extramural vascular invasion

References

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 74(3), 229–263 (2024).

Liu, C., Chen, J. & Liu, Y. Rechallenge therapy versus tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) for advanced metastatic colorectal cancer: A retrospective study. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 4237 (2025).

Liu, Y. et al. Identification and prognostic analysis of candidate biomarkers for lung metastasis in colorectal cancer. Medicine (Baltimore) 103(11), e37484 (2024).

van Gijn, W. et al. Preoperative radiotherapy combined with total mesorectal excision for resectable rectal cancer: 12-year follow-up of the multicentre, randomised controlled TME trial. Lancet Oncol. 12(6), 575–582 (2011).

Iv, A. A. et al. The evolution of rectal cancer treatment: The journey to total neoadjuvant therapy and organ preservation. Ann. Gastroenterol. 35(3), 226–233 (2022).

Guida, A. M. et al. Total neoadjuvant therapy for the treatment of locally advanced rectal cancer: A systematic minireview. Biol. Direct. 17(1), 16 (2022).

Rödel, C. et al. Oxaliplatin added to fluorouracil-based preoperative chemoradiotherapy and postoperative chemotherapy of locally advanced rectal cancer (the German CAO/ARO/AIO-04 study): final results of the multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 16(8), 979–989 (2015).

Cercek, A. et al. Adoption of Total Neoadjuvant Therapy for Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 4(6), e180071 (2018).

Garcia-Aguilar, J. et al. Effect of adding mFOLFOX6 after neoadjuvant chemoradiation in locally advanced rectal cancer: A multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 16(8), 957–966 (2015).

Ciseł, B. et al. Long-course preoperative chemoradiation versus 5 × 5 Gy and consolidation chemotherapy for clinical T4 and fixed clinical T3 rectal cancer: Long-term results of the randomized Polish II study. Ann. Oncol. 30(8), 1298–1303 (2019).

Dijkstra, E. A. et al. Locoregional Failure During and After Short-course Radiotherapy Followed by Chemotherapy and Surgery Compared With Long-course Chemoradiotherapy and Surgery: A 5-Year Follow-up of the RAPIDO Trial. Ann. Surg. 278(4), e766–e772 (2023).

Fernández-Martos, C. et al. Phase II, randomized study of concomitant chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery and adjuvant capecitabine plus oxaliplatin (CAPOX) compared with induction CAPOX followed by concomitant chemoradiotherapy and surgery in magnetic resonance imaging-defined, locally advanced rectal cancer: Grupo cancer de recto 3 study. J. Clin. Oncol. 28(5), 859–865 (2010).

Petrelli, F. et al. Total Neoadjuvant Therapy in Rectal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Treatment Outcomes. Ann. Surg. 271(3), 440–448 (2020).

Zaborowski, A., Stakelum, A. & Winter, D. C. Author response to: Total neoadjuvant therapy in rectal cancer-improvement or overtreatment?. Br. J. Surg. 106(11), 1558 (2019).

Fokas, E. et al. Randomized Phase II Trial of Chemoradiotherapy Plus Induction or Consolidation Chemotherapy as Total Neoadjuvant Therapy for Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer: CAO/ARO/AIO-12. J. Clin. Oncol. 37(34), 3212–3222 (2019).

Giunta, E. F. et al. Total neoadjuvant therapy for rectal cancer: Making sense of the results from the RAPIDO and PRODIGE 23 trials. Cancer Treat. Rev. 96, 102177 (2021).

Hong, T. S. & Ryan, D. P. Adjuvant Chemotherapy for Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer: Is It a Given?. J. Clin. Oncol. 33(17), 1878–1880 (2015).

Mroczkowski, P. & Dziki, L. Total neoadjuvant therapy in rectal cancer - improvement or overtreatment?. Br. J. Surg. 106(11), 1558 (2019).

Fernández-Martos, C. et al. Effect of Aflibercept Plus Modified FOLFOX6 Induction Chemotherapy Before Standard Chemoradiotherapy and Surgery in Patients With High-Risk Rectal Adenocarcinoma: The GEMCAD 1402 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 5(11), 1566–1573 (2019).

Ludmir, E. B. et al. Total neoadjuvant therapy for rectal cancer: An emerging option. Cancer 123(9), 1497–1506 (2017).

Jin, J. et al. Multicenter, Randomized, Phase III Trial of Short-Term Radiotherapy Plus Chemotherapy Versus Long-Term Chemoradiotherapy in Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer (STELLAR). J. Clin. Oncol. 40(15), 1681–1692 (2022).

Bahadoer, R. R. et al. Short-course radiotherapy followed by chemotherapy before total mesorectal excision (TME) versus preoperative chemoradiotherapy, TME, and optional adjuvant chemotherapy in locally advanced rectal cancer (RAPIDO): A randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 22(1), 29–42 (2021).

Sloothaak, D. A. et al. Optimal time interval between neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and surgery for rectal cancer. Br. J. Surg. 100(7), 933–939 (2013).

Terzi, C. et al. Randomized controlled trial of 8 weeks’ vs 12 weeks’ interval between neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and surgery for locally advanced rectal cancer. Colorectal. Dis. 22(3), 279–288 (2020).

Lim, Y. J., Kim, Y. & Kong, M. Adjuvant chemotherapy in rectal cancer patients who achieved a pathological complete response after preoperative chemoradiotherapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 9(1), 10008 (2019).

Dossa, F. et al. Association Between Adjuvant Chemotherapy and Overall Survival in Patients With Rectal Cancer and Pathological Complete Response After Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy and Resection. JAMA Oncol. 4(7), 930–937 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We extend our heartfelt gratitude to all the researchers involved in this study for their dedication and contributions.

Funding

The study was funded by Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (Grant number: 2023J011237) and Fujian Provincial Health and Family Planning Research Talent Training Program (Grant number: 2019-ZQN-15).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Qing Ye and Feng Huang designed the study. Changjiang Chen, Shengyuan Liu, Yangming Li and Jinliang Jian collected the data. Changjiang performed the statistical analyses. Qing Ye wrote the manuscript. Feng Huang took responsibility for obtaining permission from all co-authors for the submission of any version of the paper and any changes in authorship. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Fujian Cancer Hospital. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardian(s).

Consent for publication

We have obtained consent from all authors and participants, and they have agreed to publish the results of this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ye, Q., Chen, C., Liu, S. et al. Safety and efficacy of individualized modified total neoadjuvant therapy for low locally advanced rectal cancer. Sci Rep 15, 27068 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12416-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12416-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Multiparametric MRI radiomics nomogram predicts synchronous distant metastasis in rectal cancer

Scientific Reports (2026)