Abstract

The traditional methods for fabricating and evaluating wear properties are inherently time-consuming and financially demanding. To address these challenges, machine learning (ML) has emerged as a potent approach in predicting the mechanical and tribological behavior of advanced materials, including Al-based composites. The primary aim of this study is to combine experimental methodologies with ML algorithms to accurately predict the wear and coefficient of friction for B4C-granite composites, thereby aiding in the design and manufacturing of materials with enhanced wear performance. The composites were synthesized using stir casting, and wear behaviour was experimentally evaluated under dry sliding conditions using a pin-on-disc tribometer, resulting in a dataset comprising 81 samples. The experiments revealed that wear loss increased with higher load and lower reinforcement percentage, reaching to 0.315 g at 2.5%, 30 N, 1.67 m/s and 1200 m, compared to minimum wear loss of 0.029 g at 7.5%, 10 N, 0.83 m/s and 600 m. Seven different supervised regression-based ML models were applied to accurately predict wear characteristics, with hyperparameter tuning conducted to ensure a robust comparative analysis. The developed model’s results were evaluated utilizing a number of statistical metrics to identify the most reliable algorithm for wear and COF prediction. These models training and validation has been performed using experimental data, demonstrated strong potential for predicting tribological behavior with high accuracy, thereby reducing the need for extensive physical testing. Among all the approaches, the Fuzzy logic model achieved the highest predictive performance with highest R2 of 0.9638 and lowest MAE of 0.0023 for wear loss and R2 value of 0.9833 and lowest MAE of 0.0059 for COF, respectively. In addition, the Pearson coefficient correlation map establishes that reinforcement percentage have strong negative correlation of (− 0.57) and (− 0.50) with wear loss and COF.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Aluminium alloys are imperative materials in diverse industrial applications due to their excellent properties, including high strength-to-weight ratio, low density, good corrosion resistance, ductility, and thermal and electrical conductivity1. Their mechanical and tribological performance, however, may not be sufficient for certain demanding applications, requiring additional enhancement. To overcome these limitations, aluminium metal matrix composites (AMMCs) have been developed by reinforcing aluminium with materials such as ceramic particles, metallic inclusions, fibers, or whiskers2. These reinforcements fall into three main categories: synthetic ceramics, agro-waste, and industrial waste3. Synthetic ceramic reinforcements like Al2O3, SiC, B4C, TiC, SiO2 etc., have been extensively used to improve AMMCs’ mechanical performance4,5,6,7,8,9,10. Despite their benefits, they often raise production costs and increase weight. This has prompted interest in alternative reinforcements that are cost-effective, lightweight, and environmentally sustainable. Agro- and industrial wastes, including fly ash, red mud, rice husk ash, quarry dust, coconut shell ash, and bamboo leaf ash, are being explored as viable, eco-friendly reinforcement materials3,11,12,13. Granite powder, a waste product from granite processing, is rich in silica and alumina (about 80–85 wt%) and is emerging as a potential reinforcement14,15. Boron carbide (B₄C), known for its exceptional hardness, low density (2.52 g/cm³), and chemical stability, remains a promising synthetic reinforcement15,16,17,18. However, further research is needed on combining synthetic and waste-based reinforcements in hybrid composites to develop sustainable, high-performance materials.

Over the past decade, the field of tribology has witnessed substantial progress through the integration of machine learning (ML) techniques for the prediction and evaluation of key tribological properties19. ML regression models have empowered researchers to analyse wear mechanisms and frictional behavior with greater accuracy and efficiency. Numerous studies have successfully leveraged ML techniques, particularly artificial neural networks (ANNs) and regression based models- to predict wear behaviour and COF11,20. Critical issues still exist in spite of these developments, such as the need for larger and more representative datasets, the lack of integration between data-driven modelling and physical understanding, and the restricted investigation of various ML techniques21,22. Several investigations have validated the efficiency of ML models in predicting tribological characteristics across a range of various materials21,23,24. For instance, Dhanunjay Kumar23 utilized DT, RF, and GBR to estimate the wear rate and COF of AZ91 composites reinforced with graphene and Al2O3. Similarly, Prakash Kumar11 predicted the wear measurement of Al alloy reinforced with ZrB₂ and fly ash using ANNs and multiple linear regression model, achieving high predictive accuracy, with ANN outputs closely aligning with experimental results. Sharma et al.20 adopted the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm within an ANN framework to model the tribological behavior of rare earth oxide (REO)-Al 6061 hybrid composites, reporting a strong correlation coefficient (R = 0.987). Using response surface methodology (RSM), Sahu and Sahu24 modelled wear characteristics of aluminum 7075 composites reinforced with 8 wt% B₄C and 2 wt% fly ash, achieving a high coefficient of determination (R² = 0.9894). Additionally, Pujari et al.25 employed ANNs to predict the wear behavior of SiC nanoparticle-reinforced Al-7010 alloy, reaching a remarkable prediction accuracy of 99.663%. These studies established strong potential of ML in accurately predicting tribological features, while also emphasizing on the need for standardized methodologies to empower effective comparison.

In addition to ANNs, a range of other ML regression models have been investigated. For instance, Sauer et al.26 employed Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) to estimate the hardness of amorphous carbon coatings on ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene (UHMWPE) and revealed that GPR outperformed different competitive ML models in terms of prediction accuracy. Alagarsamy et al.27 employed the decision Tree (DT) algorithm to investigate the wear behavior of AA7075/ZnO composites, incorporating the Taguchi experimental design approach. Their findings revealed a strong correlation between the output-input features derived from the Taguchi method and the predictive capabilities of the DT model. Peng et al.28 combined convolutional neural networks (CNNs) approach integrating support vector machine (SVM) classifier to automate the identification and classification of wear particles. The hybrid method successfully reduced computational demands while improving the accuracy of classification. In another study, Prasanth et al.29 explored the effects of graphene and graphite on wear loss in AA7075-based hybrid composites using a range of ML models—including ANN, RF, and GBR—with GBR outperforming other models in prediction quality. Similarly, Bhaumik et al.30 designed a multi-additive lubricant and applied a fusion of ANN and genetic algorithms (GA) to optimize its tribological performance, yielding notable improvements.

Despite the abundance of available research, limited work has been done on the ML-based predictive modeling of tribological properties for aluminium alloy especially Al 6082-T651 reinforced with B4C and industrial waste granite powder. The present study seeks to fill this gap by applying several ML models—namely SVM, RF, KNN, ANN, DT, XGBoost, FL—to predict the wear characteristics of B₄C–granite-reinforced Al6082-T651 composites under varying dry sliding conditions. A pin-on-disc tribometer collected 81 data points throughout the dry sliding testing process. This study pursues to enhance the performance of materials and minimize experimental demands by incorporating ML-based predictive analytics. The approach is expected to support the development of high-performance, cost-efficient hybrid composites suitable for industrial use.

Fabrication and experimental methods

Fabrication process

The aluminium hybrid matrix composites were fabricated using the stir casting technique, a widely accepted and economical method for producing hybrid composites due to its ability to ensure uniform distribution of reinforcement particles. Three compositions were developed as listed in Table 1, in accordance with the specifications. The experimental setup included a control panel, mechanical stirrer, and a graphite crucible suitable for high-temperature processing. Initially, the base matrix alloy, Al6082-T651, and the reinforcing agents—boron carbide (B4C) and waste granite dust—were preheated separately at 240 °C for 1.5 h to remove moisture and enhance wettability. Following this, the preheated aluminium alloy was placed in a graphite crucible and heated to its melting point of approximately 560 ± 5 °C. Once fully molten, the pre-measured quantities of B4C and granite dust were added to the melt. To achieve uniform dispersion, the mixture was superheated to 630 °C and mechanically stirred. The resulting molten composite was then poured into a preheated graphite mould of dimensions 140 × 90 × 10 mm³ and allowed to cool under ambient conditions for about 35 min. After solidification, the composite blocks were removed from the mould, cut to the desired dimensions using a power hacksaw, and subjected to finishing operations. The specimens were prepared for testing in strict accordance with ASTM standards.

Experimentation

The dry sliding wear behavior of the fabricated samples was evaluated using a Pin-on-Disc tribometer (Magnum Engineers, Fig. 1) at the Tribology Laboratory, MNIT Jaipur. The preparation and testing of samples followed the ASTM G99-95 standard protocol. Wear experiments were performed under varying operational parameters, including applied loads of 10 N, 20 N, and 30 N; sliding distances of 600 m, 900 m, and 1200 m; and sliding velocities of 0.83 m/s, 1.25 m/s, and 1.67 m/s, as summarized in Table 2. A full factorial experimental layout (3⁴ design), shown in Table 3, was adopted to comprehensively investigate the effects of these parameters. The frictional force during each test was monitored, and the corresponding coefficient of friction (COF) was determined. To enhance the robustness and reproducibility of the data, each test scenario was repeated three times, with the mean values used for further analysis. The resulting dataset was utilized for training and validating the machine learning models, as elaborated in Sect. “Machine learning methodology”.

Machine learning methodology

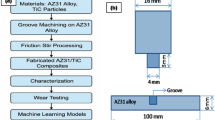

This section outlines the application of regression analysis of different supervised machine learning (ML) models in predicting and analysing the correlation between input process variables and output tribological characteristics, i.e. wear and COF. The ML models were utilized for enlightening the influence of input parameters such as percentage reinforcement, normal load, velocity and sliding distance on target tribological features of developed composite formulations. Through efficient data analysis, regression models of supervised ML uncover non-trivial patterns and complex relationship among variables that may not be explained effectively through manual analysis. In addition, these supervised ML models when trained successfully with higher accuracy can predict and provide greater understandings of the correlation in input and output variables, thus outperforming conventional statistical techniques. In the realm of developing accurate ML models, three important steps are utilized for explaining the tribological features of prepared composite formulations. The critical steps are data acquisition, preprocessing and normalization, hyperparameter tuning and ML model selection. These steps are important in achieving enhanced ML model accuracy in predicting wear and COF and their effective evaluation. Figure 2 visualizes the steps of adopted methodology beginning from data collection to diverse analysis justifying the tribological performance and their analysis.

Data acquisition, preprocessing and normalization

The enriched features dataset provides a formidable base in accurate ML predictions of output features, effect of input parameters interaction and underlying correlation of input-output variables. In the same context, present research compiled input datasets as percentage reinforcement, normal load, velocity and sliding distance, from 81 experimental trials on pin-on disc set-up and measured the target tribological features of wear and COF. The percentage weight reinforcement of B4C in Al6082-T651 matrix considered are 2.5%, 5.0% and 7.5%, while normal loads of 10 N, 20 N and 30 N are applied in tribological experimental trials. Similarly, the sliding velocity of 0.83 m/s, 1.25 m/s and 1.67 m/s with sliding distance of 600 m, 900 m and 1200 m are utilized for tribological characterization of hybrid Al6082-T651 composite in dry sliding environment. The selection of different weight% of B4C reinforcement, varying levels of normal load, sliding velocity and distance were selected based on their impact on wear and COF features of hybrid composites in literature. The resulting 81 datasets are arranged in columns with four input features and two output variables, thus providing important understanding of COF and wear behaviour of prepared hybrid composites.

The next step after data acquisition is pre-processing and normalization for realizing all datasets with different characteristics on same scale, which are decisive in attaining preferred conclusions and assists in reducing the variability. The pre-processing involves removal of duplicate data, filtering noisy or outliers, error minimization, adequate filling of missing values, etc. To this end, 81 experimental datasets was thoroughly assessed for any possibility of missing values, errors and inspected for any scaled values. Furthermore, the pre-processing data was sufficiently jumbled and then categorized into training (70%) and testing (30%) datasets as determined to conquer any remaining variability. The supervised ML model’s prediction accuracy was significantly influenced by testing datasets quality, while training data is critical in educating ML models about the complex correlation among diverse input and output features. Moreover, the process of data normalization involves transforming training and testing datasets input features considering different properties within interval of 0 and 1, which is realized with average of 0 and standard deviation of 1. The data normalization was performed utilizing Standard-Scaler function of sklearn pre-processing library in python environment.

Machine learning techniques

The tribological features like COF and wear behaviour in composites have been precisely analysed and predicted utilizing various supervised ML techniques. Moreover, selecting an adequate ML model for prediction of output properties depends on input and output features correlation and nature of datasets. For instance, the linear correlation requires linear regression models while nonlinear regression models such as support vector regression and decision trees are required for explaining complex relationships. Figure 3(a) demonstrates the variation in tribological features i.e., wear and COF of hybrid composites based on different input parameters individually, which is efficient in realizing the linearity measure among both features. The scatter dots showed respective target feature value in relation to corresponding input parameters observations, while regression line based on scatter dots determines correlation between input and output variables. It is clearly evident that wear behaviour shows non-linearity in three out of four input parameters i.e., reinforcement weight%, normal load and sliding velocity. However, sliding distance only appears to display approximately linear performance with wear characteristics. Similarly, scatter plots and regression line variation of COF for specific input parameters are illustrated in Fig. 3(b). It is revealed that all the input parameters showcased non-linear relationship with target COF features, thus uncovering complex and non-linear correlation among input-output variables. Such complexity and non-linearity among input and output features demands techniques that can successfully resolve such correlations and explain the complications in decisive manner.

For further validating the need of non-linear techniques in prediction of tribological features, the multivariable linear least square regression (MLLSR) model was exercised for evaluating the wear behaviour and COF of hybrid Al6082-T651 composites. The MLLSR model predict the wear and COF features in terms of evaluation metrics like root mean square error (RMSE) and coefficient of determination (R2). Precisely, the MLLSR model successfully predicted wear behaviour and COF with their RMSE values as 0.2474 and 0.0447, while the R2 were attained as 0.6382 and 0.8121, respectively. Such small R2 values indicates that the model can explain only 63% and 81% of variability in the model in wear and COF prediction, respectively. Therefore, this also justifies the requirements of non-linear regression models for efficient prediction of tribological performance.

Keeping in mind the aforementioned discussions on inadequate prediction of MLLSR models in precisely predicting the tribological properties of hybrid composites, this work exercises seven different non-linear regression models like support vector machine (SVM), random forest (RF), K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), artificial neural networks (ANN), decision trees (DT), extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost) and fuzzy logic (FL). These models were executed in python environment considering sklearn and seaborn libraries for regression modelling and visualization, respectively31. The seven models were explained in following sections showcasing their procedures and functioning in prediction of tribological characteristics.

Support vector machines (SVM)

Support vector machines are supervised soft computing approach introduced by Vapnik in 199832, which is based on statistical learning concept. Initially, the SVM theory was employed for classification and regression problems. The prime motivation of SVM utilizing in current work is to utilize kernel functions for establishing a hyperplane considering non-linear mapping in an infinite search space with defined margin for efficient regression model that best suited the given datasets. The nearest datasets of different classes (single input parameter and single output) within these hyperplanes are known as support vectors, which are utilized for maximizing the margin as shown in Fig. 4 and minimizing prediction error. The SVM procedure approximates data points and mapped non-linear relationships through generating optimal hyperplane and minimizing error margin \(\:\parallel\zeta\:\parallel\) encompassing all data points. Let us consider two separate datasets represented by \(\:\left\{\left({r}_{1},\:{s}_{1}\right),\dots\:,\left({r}_{n},\:{s}_{n}\right)\right\}\), where \(\:{r}_{i}\in\:{V}^{d}\) described as dataset vector in \(\:d\) dimensional solution range and \(\:{s}_{i}\) \(\:\in\:\left\{-1,\:1\right\}\) defined as output datasets. An optimal separator hyperplane function of SVM can be expressed as shown in Eq. (1).

where \(\:v\:\varepsilon\:{R}^{n}\) and \(\:l\:\varepsilon\:R\), \(\:\alpha\:\) is represented as weight vector and considered normal to hyperplane function, while \(\:l\) is considered as bias. The SVM method utilizes \(\:\varnothing\:\left(x\right)\) for mapping non-linear correlations through establishing optimal hyperplanes and minimizing the error margins \(\:\parallel v\parallel\) containing all data points of different classes. The expression for minimizing the error can be represented as shown in Eq. (2).

where \(\:c\) is considered as the regularization penalty factor, \(\:{\xi\:}_{i}\) and \(\:{\xi\:}_{i}^{*}\) are slack parameters. The parameter \(\:\epsilon\:\) indicates the size of margin and reveals the optimization efficiency. The important hyperparameters affecting SVM accuracy are \(\:c\), \(\:{\xi\:}_{i}\) and kernel basis function that transform the data into higher dimensional space. With proper selection of these hyperparameters, an accurate and reliable prediction of wear behaviour and COF can be easily realized. The Lagrange’s function was utilized for solving the non-linear regression equation as shown in Eq. (3).

where \(\:k({x}_{i},\:{x}_{j}^{*})\) denoted Kernel function. Some typically used kernel functions are linear, polynomial, sigmoid and radial basis function (RBF), of which RBF is most renowned and have exceptional performance in prediction of target features28,29,30. The RBF kernels can be expressed as shown in Eq. (4).

Random forest (RF)

The random forest model is one of the popular and powerful ML algorithms that employs a forest of decision trees and extracted features of training datasets for self-education and effective prediction33. The importance of RF models was tested in literature and proven its worth as an effective method in handling high dimension datasets and multivariate regression problems. In realm of constructing suitable RF models, several uncorrelated decision trees are constructed, making it like a forest, thus providing an adequate outcome considering input predictor features and different training datasets as shown in Fig. 5. The mean or majority results of such high number of decision trees provides a consistent and reliable outcome, yielding the accuracy in RF predictions. In a decision tree formation, internal nodes implemented trials on given input features, branches indicate the outcomes of those tests, and leaf nodes serve as the corresponding regression values as predictions. The number of decision trees and maximum tree depth in RF models have significant impact on prediction of results as higher decision trees may overfit the model, while lower decision trees may underfit the model. In addition, the selection of partial features from input variables or all input datasets features may also affect the solving of nonlinear regression problems. The RF model is significant in providing crucial understandings on input features affecting high dimension problems with multiple target variables.

K-Nearest neighbours (KNN)

The K-nearest neighbour (KNN) method is a widely recognized supervised ML model that has successfully addresses the challenges of non-linear regression and classification problems34. In KNN, the prediction for new datapoints outputs is performed utilizing K nearest neighbour data points in terms of mean distance measurements from training datasets and using their values to deduce the results for new datasets as shown in Fig. 6. The number of nearest neighbours is critical in adequate fitting and versatility of regression model, which can be carefully selected based on complexity of the problems and nature of datasets. The KNN algorithm measured distance between datasets using Euclidean distance formula and thus, can efficiently portray the non-linear correlation among input and output variables without taking assistance from any hypotheses. Typically, with correct selection of number of neighbours and adequate distance measure, the effectiveness and robustness of KNN technique can be improved, however, k-cross validation and weighing schemes also empowers KNN for prediction in convex and high dimensional datasets.

Artificial neural network (ANN)

The ANN is a powerful and well-recognized ML model utilized in solving diverse non-linear problems by emulating human brain neurons working and their interconnected layers35. The most common example of ANN model is multilayer perceptron (MLP), which involves an input layer, definite hidden layers and one or more outcome layers as shown in Fig. 7. The input parameters are defined in input layer, while response variables are obtained at output layers attaching with hidden layers interconnected considering weights (\(\:{w}_{ijk}\)) and biases (\(\:{\beta\:}_{ijk}\)). The training of ANN model was typically executed employing back propagation method for minimizing mean square error, producing desirable outcomes, although these are insufficient in enhancing the accuracy of ANN prediction owing to local minima stagnation in hyperparameters solution spaces. In literature, the use of ANN models is eminent and have shown improved prediction performance for diverse composite features consisting of mechanical and tribological characteristics. Moreover, the efficiency of ANN models highly depends on internal parameters like activation function, number of neurons, weights, biases, number of epochs, etc. The optimal selection of these parameters governs the efficacy and consistency of ANN models in solving complex non-linear problems, which are troublesome to solve using conventional methods.

Decision trees (DT) model

The decision tree (DT) theory deals with categorized tree-like subset of the input features (in this case reinforcement percentage, normal load, velocity and sliding distance). The prime motivation of this method comes from realizing efficient target features values in tackling multivariate non-linear problems. The DT concept is applicable in classification as well as regression tasks depending on whether the target feature is discrete or continuous. The DT consists of a single root node which is considered as top decision node having best predictor efficiency. The root node has different branches to decision (or internal) nodes and leaf nodes as shown in Fig. 8. Specific decision node has two or more branches with representing a test on features revealing yes or no as solution taking the branches to next leaf node or other internal nodes. The primary goal of DT models is to design an optimal partition of decision nodes with consistency considering minimum MSE or RMSE values. The outcome of DT model is greatly affected by its internal parameters such as minimum samples for a leaf node, maximum depth, etc., thus reducing the chances of overfitting of model.

Extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost) model

The extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost) algorithm is considered as a robust and powerful supervised ML model offering the strengths of high generalization capabilities and efficient prediction performance in classification and regression problems36. The XGBoost working procedure is based on decision trees, and each tree aims to minimize the error of its preceding tree. Therefore, transforming the weak learning tree into a strong learning tree by employing the residues of latter. Each generation of XGBoost model results in efficient predictions by minimizing the loss functions, which results from adding the individual outcomes of current learning tree and previous learning trees. In order to obtain best predictions by minimizing loss error to minimal, XGBoost iteratively grows along with pruning of decision trees, thus refining the predictions at specific leaf node. The loss function to be minimized is expressed in Eq. (2).

where \(\:{y}_{i}\) and \(\:{x}_{i}\) are considered as input and output parameters, \(\:{\Omega\:}\) denoted regularization factor. The prediction accuracy of XGBoost models may be upgraded by adequately optimizing the value of its hyperparameters like child weight, max tree depth, learning rate and tree counts to be fitted.

Fuzzy logic (FL) inference system model

The theory of Fuzzy logic has been employed by past researchers in analysing and predicting diverse features of hybrid composites, proving it as a versatile and intelligent tool employed for decision making challenges and prediction of complex systems37. The concept of FL is very much applicable in applications where vague, uncertain or uncorrelated data existed. Figure 9 demonstrated the flow diagram of fuzzy logic with its critical components. The component of FL includes fuzzifier, inference system, rule base, de-fuzzifier. The fuzzifier transform real world values or crisp values into fuzzy sets (such as low (L), medium (M) and high (H)) utilizing the power of membership functions. These set of fuzzy inputs are fed to fuzzy inference system for its processing using a definite set of if-then rules defined in rule base. The inference engine provides fuzzy outputs which are fed to de-fuzzifier block to convert it into crisp output values. The membership functions are critical in defining rule bases which maps fuzzy inputs to fuzzy responses, thus aids in enhancing the prediction consistency and accuracy of FL models. Some of commonly used membership functions are triangular, trapezoidal, gaussian, G-bell, etc. The present study employed gaussian membership functions based on lower RMSE value among different membership functions.

Hyperparameter selection for different ML models

The hyperparameters are notable parameters of a particular supervised ML model that controls the knowledge, learning efficiency and empowered the prediction efficacy of each regression technique. The process of hyperparameter tuning compels choosing best possible values of regression model’s internal parameters to boost its performance in handling higher dimension datasets. Before training of individual models, these parameters have to be defined considering problem scalability and complexity. In the current study, the hyperparameters of all seven models were selected based on n-fold cross validation and after evaluating their performance across various permutations and combinations. Considering the specific model’s satisfactory outcome, it is selected for execution on test datasets to get a fair estimate on new and unseen datasets. However, if the performance is unsatisfactory, the hyperparameter tuning process is continued and repeated with different permutations of parameters. The process of optimal hyperparameter selection proved to be a repetitive progression involving recurrent training and assessing numerous models till succeeding to obtain a reasonable outcome for wear and COF. Through such rigorous procedure, hyperparameters of all models are recorded and shown in Table 4.

Results and discussion

The aim of this research is to evaluate how individual factors affect the wear and COF in Al6082-T651 hybrid composites. This analysis is essential for determining a composite material capable of enduring varying applied loads, sliding velocities, and sliding distances. To achieve this, a full factorial experimental design was employed, comprising 81 trials that incorporate four variables—denoted as R, L, D, and V—each examined at three distinct levels. The results obtained from these experiments are presented in Table 5.

Influence of load

Figure 10 illustrates the correlation between the applied load and the resulting changes in both wear and COF for hybrid composite materials. To investigate these complex relationships, a series of tribological experiments were carried out at a constant sliding speed of 0.83 m/s, with sliding distances ranging from 600 m to 1200 m. The results indicate a consistent increase in wear loss across all composite samples as the applied load rises, while the COF shows a decreasing trend with increasing load. Among the tested composites, the sample contains maximum weight% of reinforcement (denoted as HC3) demonstrated the best resistance to wear. This improvement is attributed to the higher reinforcement level, which enhances the composite’s hardness and mechanical strength. Specifically, the HC3 composite recorded a 37.91% reduction in wear loss under a 30 N load compared to a 10 N load at a sliding distance of 600 m (Fig. 10a). A similar trend was observed at a sliding distance of 1200 m, where HC3 showed a 9.75% improvement in wear resistance under the same loading conditions (Fig. 10e). The increased wear at higher loads can largely be attributed to intensified friction at the contact interface between the pin and disc, which accelerates material detachment from the pin surface. Moreover, all hybrid composites tested outperformed the base alloy in terms of wear resistance under identical load and sliding velocity conditions38. The observed rise in wear loss with increasing load across all specimens is primarily due to enhanced plastic deformation caused by the elevated stress levels38,39,40.

At lower applied loads, the contact between interacting surfaces is minimal, which typically results in reduced material loss due to wear in the fabricated samples. In contrast, as the load increases, the intensified surface interaction leads to greater wear and a noticeable decline in wear resistance41. However, during wear testing, the incorporation of reinforcement particles within the material played a crucial role in counteracting the effects of higher loads. These particles functioned as obstacles to deformation, thereby limiting plastic flow and substantially improving the material’s resistance to wear38,39,41.

The frictional behavior demonstrated a trend opposite to that of wear, with the COF declining as both the applied load and the reinforcement content increased. The maximum COF value of 0.278 was noted for the HC1 sample under a 10 N load, whereas the minimum value, 0.17, was recorded for the HC3 sample under a 30 N load. This reduction in COF with higher applied loads and increased reinforcement content is mainly due to the thermal softening of the contact surface during sliding. At elevated loads, wear debris tends to accumulate between the sliding surfaces, forming a third-body layer that facilitates friction reduction. Furthermore, the higher temperatures generated under these conditions promote the degradation of surface asperities, leading to the formation of a lubricating layer that reduces shear stress between the pin and disc. This effect contributes significantly to the observed decrease in friction. A similar trend was reported by Zhao et al.41, who found that aluminum alloys reinforced with TiB2 showed a more pronounced decrease in COF compared to those reinforced with SiC particles20,42.

Influence of sliding velocity

Figure 11 presents the influence of sliding velocity on both wear loss and the COF in the hybrid composite samples. The tribological tests were carried out under varying loads ranging from 10 to 30 N and sliding velocities between 0.83 and 1.67 m/s, with a fixed sliding distance of 1200 m. As shown in Fig. 11, an increase in sliding velocity generally led to higher wear. For instance, the HC3 composite experienced a 10% reduction in wear at 10 N when the velocity increased from 0.83 m/s to 1.67 m/s. At a higher load of 30 N, wear reduction was even more significant—approximately 55%—when the velocity increased to 1.67 m/s under the same load conditions. This trend is likely due to shorter contact durations at higher speeds, which limit the time available for wear mechanisms to act. Additionally, the frictional interaction between the pin and disc generates heat, elevating their surface temperatures43,44. As indicated in Fig. 11, the COF tends to decrease with increasing sliding velocity. This decline is attributed to the development of a mechanically induced mixed layer at the pin-disc contact zone43, which acts as a lubricating film. At lower velocities, the roughness of the initial contact surfaces causes more pronounced mechanical interlocking, leading to higher friction. As the test progresses and wear smoothens these surfaces, the COF gradually decreases43,44.

Influence of sliding distance

Figure 12 presents the relationship between sliding distance and both wear loss and the coefficient of friction (COF) for the tested composites. The experiments were conducted at a constant sliding velocity of 0.83 m/s, with sliding distances ranging from 600 to 1200 m. The results indicate a clear trend: as the sliding distance increases, both wear loss and COF also rise. This effect becomes more significant under higher applied loads which may be attributed to the generation of thermal energy at the contact interface during abrasive wear. With increasing sliding distance, the accumulation of heat may lead to material softening, thereby weakening the bond between the reinforcement particles and the matrix. As a result, the particles are more easily displaced, accelerating wear. Furthermore, this behavior could be linked to the destabilization of the tribolayer at extended sliding distances. Comparable observations of increased wear with longer sliding distances have been reported in previous studies23,45. The rise in COF observed at greater sliding distances, as shown in Fig. 12, can be attributed to a greater number of asperity interactions. This enhances the presence of hard phases at the interface, thereby increasing the frictional force and, consequently, the coefficient of friction38,39,41,42.

Influence of reinforcement proportion

The integration of reinforcement within the matrix is known to play a crucial role in enhancing the mechanical strength of composite materials. Improved interfacial bonding between the reinforcing phase and the matrix leads to increased stiffness and mechanical resistance. As depicted in Fig. 13, the inclusion of reinforcement materials also contributes to a noticeable rise in the composite’s hardness, which in turn enhances its wear resistance and reduces material loss due to wear. Among the tested samples, the HC3 composite exhibited the least wear, indicating superior performance. Moreover, the coefficient of friction (COF) was observed to decline with higher reinforcement content, as shown in Figs. 10, 11 and 12. This reduction in COF is likely due to the presence of hard reinforcement particles that reduce the effective contact area between the pin and disc surfaces. Further insights into the morphological aspects associated with this behavior are presented in Sect. “Conclusions”.

Surface morphology

Figure 14 display SEM micrographs taken from three different regions on the worn surfaces, illustrating the surface morphology in both severely and mildly worn areas of the hybrid composites. The experimental findings revealed that HC1 underwent the most significant wear under a load of 30 N, sliding velocity of 1.67 m/s, and a total sliding distance of 1200 m. In contrast, HC3 exhibited the least wear when tested at a lower load of 10 N, velocity of 0.83 m/s, and distance of 600 m. Overall, the wear behavior of the composites was governed by multiple mechanisms, including adhesion, abrasion, delamination, and oxidation38,39,41,42. The presence of parallel grooves, as seen in Fig. 14, suggests the occurrence of abrasive wear. Such grooves are typically formed when a hard counterface moves against a softer material, causing surface displacement and subsequent material removal in the form of well-defined tracks43. The surface of the pin also exhibited signs of oxidative wear, primarily due to the heat generated by friction during operation. Moreover, the accumulation of wear debris on the pin was attributed to plastic deformation. The emergence of layered structures and fine cracks, resulting from the detachment of wear particles, is a hallmark of delamination wear44,46,47. The observation of cracks and voids on the worn surfaces’ points to material delamination, a process characterized by surface deformation, the initiation of cracks, and their subsequent propagation. Evidence of ploughing and crater formation on these surfaces further suggests the occurrence of plastic deformation. Notably, the surface subjected to more severe wear (Fig. 14a-c) displayed wider grooves and more extensive ploughed areas than the surface experiencing lower wear (Fig. 14d-f). At a higher applied load (L = 30 N), both the depth and width of the grooves increased, indicating that abrasive wear becomes more dominant under elevated loading conditions. Additionally, the presence of oxygen on the worn surfaces supports the occurrence of oxidative wear, likely resulting from the thermal effects generated during the sliding motion that promote surface oxidation. The high concentration of reinforcements in HC3 led to increased frictional heat generation, which in turn intensified the oxidation of the surface. This oxidation resulted in the formation of a protective oxide layer that minimized direct interaction between the abrasive sliding surfaces, thereby enhancing the composite’s wear resistance.

Evaluation of machine learning regression models

This section discusses the tribological behaviour analysis of hybrid Al6082-T651 composites exercising seven supervised ML models, which assists in determining the influence of input parameters on target features of wear and COF along with their correlation. The experimental trials and wear mechanism explained in previous sections have provided important insights in development of these prediction models with enhanced prediction capabilities for wear and COF under dry sliding conditions. The evaluation metrics considered for assessing the accuracy and consistency of developed ML models in prediction of COF and wear behaviour are mean square error (MSE), root mean square error (RMSE), mean absolute error (MAE), coefficient of determination (R2) and mean absolute percentage error (MAPE). These evaluation measurements are critical in realizing how closer the developed supervised regression model’s outcomes are to the actual experimental values of target features of hybrid composites. The parameter MSE denotes mean of squared differences between the experimental and ML model’s predicted values, while RMSE defined as the square root of MSE output. The MAE represented as the mean of absolute difference between ML predicted and actual experimental values. Similarly, the value of MAPE defined the mean of absolute error in percentage terms. These four evaluation measurements provide average of difference in ML model’s predicted values with experimental values in different forms, with ascertaining model’s efficacy having lower values in this system of measurements. Contrast to these evaluation metrics where low values are desirable for goodness of fit, the R2 represents the degree to which the independent parameters successfully explained the variation in results of target features, i.e. wear and COF. Therefore, the higher value of R2 is desired (closer to 1) to justify the explanation of most of output variables in adequate comparison of all ML models results. The R2 measured value ranging from 0.9 to 1 revealed superior ML model having outstanding prediction characteristics, while lower than 0.9 is considered as moderate fit, which suggests the model inefficacy in explaining the output results. The results on these numerical metrics for wear and COF of hybrid Al6082-T651 composites are recorded in Tables (6–7) for seven supervised ML models in this study.

Table 6 shown that the SVM realized a MSE value of 0.0002, quantifying the average of squared error for predicted and experimental wear, while overall RMSE obtained as 0.0138. The MAPE % is within acceptable limits of 7.39 for SVM model justifying its prediction efficacy. The MAE showcased that SVM predicted wear values on average deviate by 0.0007 from wear experimental values. In addition, the SVM have superior \(\:{R}^{2}\) value of 0.9563 from most of the ML models, thus maintaining its efficacy in explaining almost 96% of variability in recommending accurate wear values. The RF model provides higher MSE and RMSE than SVM with 0.0031 and 0.0558 showcasing more overall prediction deviation in wear values. The MAE for RF demonstrated is slightly higher than SVM with 0.0118 showing average prediction deviations in all wear values. The RF model achieved an R2 value of 0.8997, suggesting its inability to explain nearly 10% of variances in the results, thus realizing a lower accuracy in prediction. Also, KNN model obtained MSE and MAE values of 0.0018 and 0.0087, respectively, which is comparatively higher than the errors of SVM model. The MAPE of 13% is also at higher side, while R2 value of 0.8975 suggested a better explanation of results than RF regression models but inferior to SVM model. Similarly, ANN have performed superior to RF and KNN in terms of MSE and RMSE with values of 0.0004 and 0.0197, respectively, while MAE of ANN is nearly comparable with SVM demonstrating its efficacy in accurate prediction of wear of hybrid composites. The ANN model also exhibited remarkable performance with explaining all variability in results having accuracy of nearly 94.1%. Moreover, the DT model have lowest MSE, however its MAE and MAPE percentage values are worst 0.0218 and 23.55, which established that its prediction errors are on higher side and have average deviation of nearly 23% in each of wear values from experimental value. The same explanation can be realized by the worst R2 value of 0.6502, depicting the DT model can explain only 65% of variability in wear results. In contrast, XGBoost attained the lowest MSE value of 3.3659E-05 with MAE of 0.0084, demonstrating lower prediction errors in wear values. The MAPE has been under acceptable limits of 9.77%, exhibiting overall average error within tolerable range. The higher R2 demonstrated its robustness and accuracy in explaining 94% of variability in wear results. Finally, the FL model exhibited significantly lower MSE, RMSE and MAE values of 0.0003, 0.0171 and 0.0023, which revealed lower prediction errors, thus highlighting greater accuracy. The average error in all wear predicted values are also at lowest level of 6.2247, while the R2 value of 0.9638 have outperformed all models in explaining the variance, only approximately 3% variance in results are not explained, thus revealing exceptional accuracy.

Figure 15 illustrated the predicted versus experimental (actual) wear plots using all seven developed ML regression models on test datasets. The corresponding values of R2 for specific models have also been included inside the individual plots. It is worth notable that FL model has demonstrated superior accuracy with remarkable R2 value of 0.9638, which confirms that FL model can successfully predict the wear behaviour of hybrid composites with 96.38% accuracy on new datasets. The next best ML models are SVM, ANN and XGBoost with R2 value of 0.9563, 0.9410 and 0.9408, respectively, displaying equivalent prediction accuracy in prediction of wear. In contrast, the KNN model and RF model have also adequately performed, however, higher deviations in average error shows restriction in accurately predicting wear performance for non-linear and complex correlated datasets. Moreover, the performance of FL and SVM may be credited to its competence in tackling the challenges of complex correlation among input variables and target feature. The fuzzy logic utilized gaussian membership functions with three fuzzy levels for efficient transformation of crisp values into fuzzy sets, thus empowering prediction of wear through underlying rule base and allowing it to describe intricate correlation within the datasets. Similarly, SVM performance have been aided by its radial basis function and regularization parameter, that efficiently balances the margin width and explained the underlying variances in the complex correlated data. In contrast, RF and DT models were unable to capture the underlying patterns in the datasets, owing to their overfitting of models, non-optimal hyperparameters, complex outliers and dataset features the concisely contributed to low performance of these regression models in prediction of wear behaviour of hybrid composites.

Furthermore, for enhancing the consistency and validation of different ML models performance in prediction of wear behaviour, residual plots are exercised and displayed in Fig. 16(a-g). The residuals are defined as the deviation of predicted wear values from actual experimental values, which are utilized as diagnostic plots in confirming the qualitative performance and accuracy information of the developed ML models. Each residual plot is combination of four sub-plots for analysis and better comparison of ML models. Figure 16 (a) displayed first plot depicting no trend and residuals are uniformly distributed around zero line, while the second plot showed histogram of standardized residuals. The histogram suggested that residuals have roughly uniform distribution with very few outliers confirming the residual distributions in first plot. The third plot demonstrated that all residuals are align closer to 45° inclined line with one outlier, thus verifying normal distribution. All coefficients in autocorrelation function (ACF) plot comes within the 95% confidence interval, implying the non-existence of autocorrelation and demonstrated that model successfully identified and explained all relationships among datasets.

Figure16 (b) showed that residuals are randomly distributed, and no patterns are visible, which showed there’s no problem of heteroscedasticity. However, there are few outliers which are confirmed by histogram plot of standardized residuals. In addition, the histogram of residuals confirms right side skewness indicating deviation from normality. The third plot demonstrated that all residuals are align closer to 45° inclined line with few outliers, thus drift from normal distribution specifically top ultimate values. The final plot of RF residual showcased all coefficients have low autocorrelation except for one, thus showing limitations of RF models in accurate prediction of wear and non-competence in explaining underlying complexity. Figure 16 (c) depicted KNN diagnostic residual plots with no evident trends or patterns in the residuals. The histograms are more normally distributed than RF results, while some of the residuals are outliers specifically at extreme bottom in Q-Q plot. In addition, all the coefficients have low autocorrelation and fall within the confidence interval. The aforementioned results for residuals depict KNN’s goodness of fit. However, low R2 value of 0.8975 revealed that KNN is unable to handle the underlying complexity and variability in wear datasets having non-linear relationship with input variables. This can be due to comparatively lower data for training to restrict KNN to understand the hidden complexity and correlation between input-output features. Figure 16 (d) depicted ANN residual plots indicating good fit with no decisive pattern of residuals. The histogram of residuals is equally distributed and centred around zero suggesting an approximate normal distribution. The Q-Q plot suggested residuals are falling on inclined line with one outlier at extreme top. The low autocorrelation coefficients revealed independence of residuals. It is worth noting that DT showed worst residual performance with standardized residual histogram shown non-uniform variation of residuals which does not follow normal distribution. The first plot of DT model (see Fig. 16 (e)) demonstrates several outliers and are not symmetrical to zero line confirmed by the unbalanced histogram residuals. This suggests an inconsistent relationship between residuals and predicted values. Moreover, the Q-Q plot and ACF plot confirms significant variances in residuals with deviations from normal distribution and high autocorrelation. Such low performance of DT may be attributed to inability in explaining correlation between input parameters and target features. Also, the minimal R2 of the DT model implies its restricted capacity to clarify substantial variance deviation. The inherent problem of DT model is its probable overfitting which can influence DT model’s inadequate performance in acquiring and describing the fundamental relationships in the datasets. The XGBoost model have also shown that variance is uniform, and no specific patterns is evident with one or two outliers (see Fig. 16 (f)). The residuals are roughly normally distributed all residual align with centre line and only one data shown significant deviation. As shown in ACF, the model showed one autocorrelation coefficients are outside the confidence interval. Finally, the FL model showed uniform distribution of residuals supported by uniformly distributed histogram distribution plot (see Fig. 16(g)). The residuals data are closely aligning with zero line revealing homoscedastic residuals with no specific trend. All residuals are also aligning with incline line, while ACF plot shows autocorrelation coefficients are falling within confidence range. Such improved performance in residual plots support the efficiency of the FL model in successfully analysing the inherent relationships and dependencies in the datasets. Furthermore, the best R2 of 0.9638 specifies that the FL model justifies a meaningful explanation of complex variability present in the datasets. Therefore, the FL model can be deemed appropriate for additional assessment or prediction.

Additionally, Table 7 presents result on diverse evaluation metrics for COF considering seven ML models. The MSE and RMSE for SVM regression model is 0.0197, exhibiting minimum overall error among the models. The MAE of 0.0073 units represent average deviation in COF prediction values. Moreover, the higher values of R2 demonstrated enhanced capability of SVM model in explaining 94.1% of variance in COF results. The RF and KNN models depicted average and overall squared difference in predicted and experimental values as 0.0006 and 0.0245, 0.0013 and 0.0361, respectively, which is lowest in all models for COF results. Similarly, the mean deviation in prediction values, i.e., MAE measured as 0.0112 and 0.0098 units, revealing higher prediction deviation throughout COF results in these models, which is higher than SVM models. However, the R2 value of 0.9749 and 0.8933 illustrates reasonable accuracy in prediction and explaining the variation in results by RF and KNN models. The ANN model attained lower MAE than SVM, RF, KNN, thus showcasing lower prediction deviations in COF prediction results. Similarly, the RMSE of 0.0199 revealed comparable in overall mean square error with SVM. One of the highest R2 of 0.9803 reveals that ANN comprehensively explained more than 98% COF variance and less than 2% remained unexplained. The DT model surprisingly performed superior to RF and KNN models with lower MAE and RMSE values of 0.0091 and 0.0238, showing lower prediction error, however prediction deviation is higher than SVM and ANN models. The greater R2 value of 0.9521 indicated that it can explain more than 95% variance in COF outcome. The XGBoost models also improved its performance in prediction of COF features through comparatively lower MAE value of 0.0082 and RMSE of 0.0224, thus showing minimum overall error in its prediction capacity. Further, the MAPE % has also revealed lower average prediction deviation 1,48%, while considerably high R2 value of 0.9744 representing that the model effectively explain nearly 97.44% of the COF variance. Finally, fuzzy logic model demonstrates lowest MAE value of 0.0059 and combined lower MSE value of 0.0004, indicating that FL model has low average error deviation and lower prediction errors for COF in comparison to all other competitive models. The lowest MAPE percentage and highest R2 value of 0.9833 revealed that FL consistently explained all the variances in the COF output. Such outcomes indicate that the FL model is dependable and efficient in catching the original relationships and correlations in the COF feature data.

Figure 17 explained the predicted versus experimental wear plots for all seven regression models on COF test datasets. It is noteworthy that FL model has demonstrated superior accuracy with incredible R2 value of 0.9833, which approves that FL model can successfully predict the COF outcome of hybrid composites with approximately 98.33% accuracy on new datasets and can explain nearly 99% variance in results. The FL model is followed by ANN and XGBoost with R2 value of 0.9803 and 0.9744, respectively, exhibiting comparable prediction accuracy in prediction of COF. It is worth noting that DT and SVM models have also shown significant performance in explaining variation in COF results with R2 value of 0.9521 and 0.9410. Although, the KNN and RF model have performed adequately, however, their higher deviations in average error concerns restrictions in accurately predicting wear performance for non-linear and complex correlated datasets.

Furthermore, for validating the reliability and efficiency of different ML models performance in prediction of coefficient of friction, residual plots are employed, and results are depicted in Fig. 18. The residuals are defined as the deviation of predicted COF from experimental values, which are utilized as diagnostic plots in confirming the qualitative performance and accuracy information of the developed ML models. Figure 18 (a) displayed SVM residual plots depicting most of the residuals towards negative side, which revealed that developed SVM model overfits the target feature. The histogram residual plot exhibited skewness towards right side, which is also confirmed by Q-Q plot with several outliers. However, the correlation coefficients are within confidence interval. Although, the residual plots showed significant weakness in term of residual behaviour, however, the higher R2 value depicted better predictions of COF. Similarly, the RF and KNN showed similar residual behaviour uniform and random variance depicting no trend of data, thus confirming assumptions of regression models. The histogram residuals not following normal distribution for both the models specifically KNN showing right hand skewness, thus not conforming to regression assumptions. The third plot demonstrated that all residuals are align closer to 45° inclined line with one outlier, thus verifying normal distribution. All coefficients in autocorrelation function (ACF) plot comes within the 95% confidence interval, implying the non-existence of autocorrelation and demonstrated that model successfully identified and explained all relationships among datasets. The ANN and DT models plot depicts scattered residuals in their scatter plots denoting random variance in prediction of COF and homoscedasticity, while the histogram residuals, though somewhat showcased satisfactory in fulfilling the regression assumptions. The ACF plot revealing residuals coefficients fall under confidence interval as desired. Finally, the XGBoost and FL models demonstrated superior residual behaviour as shown in residual plots. The standardized residual data of FL is normally distributed with homoscedasticity behaviour and no trend, showing all the residual near to zero line. The histograms are normally distributed with Q-Q plot revealing upgraded performance by FL in comparison to XGBoost models (showing few outliers). At last, the autocorrelation is low depicting better performance for FL in explaining various dependencies and non-linear relationship between multiple input parameters and COF, thus revealing its outperformance in comparison to other ML models in understanding the underlying features and correlation.

Figure 19 demonstrated the feature importance plot for wear and COF, revealing the most important input parameters rank wise affecting target features. From Fig. 19 (a) and Fig. 19 (c), it is clearly evident that wear behaviour is mostly influenced by reinforcement percentage of B4C in Al6082-T651 hybrid composites followed by normal load and sliding velocity. The addition of reinforcement materials improves the hardness of the hybrid composite, which contributes to upgrade the wear resistance capabilities in composite, thereby reducing the wear loss. The sliding distance is the least influential parameter affecting wear loss. Similarly, Fig. 19 (b) and Fig. 19 (d) revealed that applied load is most influential factor outperforming other input parameters in its impact on COF value. The other influential parameter is reinforcement percentage of B4C affecting the COF followed by sliding distance. The sliding velocity shows no effect on COF, ranking last among input variables.

Figure 20 further visually depicted Pearson correlation coefficient map showcasing the quantitative correlation between input parameters and response variables of wear and COF. The Pearson correlation coefficient was typically employed for determining intensity and direction of non-decreasing or non-increasing correlation between different variables owing to the non-linearity of the datasets. The diverse colours in the map revealed the variation in positive and negative correlations from + 1 to −1. The coefficients near to + 1 indicate greater and positive relationship between corresponding features, while values near to −1 suggests inverse relationship among features. The increase in input parameters displays strong decreasing trend of target features. In Fig. 20 (a), it was evident from coefficient value of − 0.57 that with increasing reinforcement percentage, the value of wear loss decreases strongly. The addition of reinforcement materials enhances the hardness of the hybrid composite, which contributes to better wear resistance, thus lowering the wear loss. In contrast, with increasing the value of applied load, the wear loss shows strong positive correlation. It is evident that with lower value of applied load wear resistance can be enhanced significantly. In contrast, a coefficient of 0.35 between sliding velocity and wear loss indicates a moderate positive correlation, implying that higher sliding velocity increases wear loss. Similarly, sliding distance and wear loss have correlation coefficient of 0.21, implying weak positive correlation. This behaviour suggested that with increase in sliding distance, the heat generated intensified, causing softening of the test material, thus have slight tendency of enhancing wear loss.

Similarly, the COF metrics decreases with increasing reinforcement percentage, depicting a moderate negative correlation with correlation coefficient of − 0.50 (see Fig. 20 (b)). This behaviour may be attributed to presence of strong reinforcement particles that restrict the contact area between the pin and disc surfaces, thus enhancing friction between surfaces. Likewise, the normal load and COF have strong negative correlation with each other having coefficient as − 0.75, which suggests that with application of normal load, the friction between surface decreases significantly. This behaviour can be attributed to the accumulation of wear debris between contact surfaces contributes to this reduction in COF. Further, with 0.1 as correlation coefficient, there is a weak positive relation between sliding distance and COF, while sliding velocity has very wear negative correlation with COF. Such comprehensive assessment assists in recognizing how different input features are correlated to wear loss and COF, providing enhanced estimation and optimization of target features based on these underlying relationships.

Figure 21 depicted the violin plot for prediction of wear loss and COF of hybrid composites using different ML models, suggesting the concentration of residuals along bell-shape curve. The width of violin plot depicts the probability density of datasets. The symmetry in violin plot of FL model for wear loss, which suggested even distribution of data on both sides of median and enhanced prediction accuracy of model. The SVM model also have even distribution of datasets thus providing comparable violin plot with FL. Similarly, the FL model’s violin plot suggested more concentrated datasets, revealing better prediction accuracy of COF as shown in Fig. 22. Similarly, SVM, ANN and XGBoost performed very well in prediction of COF and have the capability to explain underlying correlation in input datasets with target features. The RF and KNN models performed worst with larger density of residual over a larger area depicting non-uniform distribution, thus not able to understand the non-linear relationship among input-output variables. Further, fuzzy logic models emerged as powerful tool to accurately predict the dependencies and underlying correlation, therefore, employed for analyse the interaction effect in the terms of three dimensional surface plots.

Figure 23 shows the surface plots depicting input parameters interaction effects on target features of wear loss and COF, which are created using MATLAB R2021a software. Figure 23 (a) shows that with higher reinforcement percentage of B4C in hybrid composites along with lowest normal load results in minimum wear loss. Figure 23 (b) illustrated that higher reinforcement of B4C with lower values of sliding velocity resulted in lowering the wear loss and enhancing the wear resistance capabilities of hybrid composites. Similarly, lower sliding distance of 600 m and highest reinforcement percentage results in enhancing the wear resistance behaviour in composite material as clearly seen in Fig. 23 (c). Figures 23 (d-e-f) suggested lower combination of normal load, velocity and normal load, sliding distance resulted in improved wear resistance performance of hybrid composite samples. Similarly, the COF values are reduced considering higher reinforcement percentage and load as shown in Fig. 23 (g). In contrast, Figs. 23 (h-i) shown that for all the values of sliding distance and velocity, the higher reinforcement of B4C in hybrid composites provided reduced COF values. Similar trend can be seen in Figs. 23 (j-l), where higher load values with any values of sliding distance and velocity results in minimizing the COF performance.

Conclusions

In this study, Al-based composites reinforced with boron carbide (B4C) and waste granite powder were successfully developed using a stir casting technique. The composites were synthesized with varying B4C weight% (2.5, 5, and 7.5). A comprehensive investigation was carried out to assess the hardness, dry sliding wear behavior, and underlying wear mechanisms of the fabricated materials. Additionally, supervised machine learning regression models were employed to predict the wear and coefficient of friction (COF) of the composites. Based on the experimental findings, the following conclusions were drawn:

-

The results clearly indicate that COF consistently decreased with increasing applied load, while the wear loss progressively increases across all composite samples. Notably, among all composites, the HC3 variant—characterized by a higher reinforcement content—exhibited superior wear resistance, attributed to increased mechanical strength and enhanced hardness provided by the greater reinforcement concentration.

-

The study revealed that wear loss increases with sliding velocity. Among the tested materials, the HC3 composite demonstrated superior wear resistance, exhibiting a reduction in wear by 10% under a 10 N load and by 55% under a 30 N load at elevated velocities. This improved performance is attributed to the shorter contact duration, which, despite the presence of frictional heating, limits material degradation. Additionally, the formation of a mechanically mixed layer contributed to lowering surface interlocking and friction, thereby reducing the coefficient of friction (COF).

-

Both wear loss and COF increased with longer sliding distances, particularly under higher applied loads. This behavior is primarily attributed to thermal softening and the weakening of the bond between the reinforcement and the matrix, instability of the tribo-layer, which leads to greater surface interactions and higher friction.

-

Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) analysis revealed distinct wear mechanisms across the tested surfaces. The most severely worn region (G1) exhibited significant ploughing, crater development, and evidence of delamination, whereas the surface of HC3 showed considerably fewer wear features. The investigation demonstrated a clear correlation between applied load and both material loss and groove depth, with HC1 under a 30 N load experiencing the greatest wear. In contrast, HC3 displayed minimal degradation, primarily due to its higher content of reinforcing material. Additionally, the presence of an oxide layer on HC3’s surface—formed as a result of friction-induced heating—was found to be instrumental in limiting direct contact between the surfaces, thereby enhancing its resistance to wear.

-

The fuzzy logic model demonstrated superior predictive accuracy for wear loss, outperforming six competitive machine learning models with an R2 of 0.9638 and a mean absolute error of 0.0023. Based on comprehensive analysis and several residual assumptions, its demonstrated strong performance in explaining the inherent correlations, complexities and structures in the given datasets.

-

Similarly, for precise prediction of COF, the fuzzy logic model again emerges with remarkable performance outclassing other compared ML models with obtaining highest R2 value of 0.9833 and lowest MAE of 0.0059. In addition, conforming to different residual hypotheses, the FL models successfully analysed and predict the underlying correlation and patterns in prediction of COF.

-

The reinforcement percentage of B4C was established as the extremely important input parameter followed by normal load in affecting the wear loss of hybrid composites, which was clearly evident from feature importance plot and its outcome. Moreover, the normal load emerges as best performing parameter influencing COF followed by reinforcement percentage.

-

The analysis of Pearson coefficient correlation demonstrates that reinforcement percentage have strong negative correlation of (− 0.57) and (− 0.50) with wear loss and COF. Similarly, load have positive correlation of (0.57) with wear loss, however strong negative correlation (− 0.75) with COF. The sliding distance and velocity are positively correlated with wear behaviour while have insignificant effect on COF.

Future work should focus on expanding the dataset to address data limitations. Therefore, techniques such as synthetic data generation and transfer learning may be explored. Additionally, integrating hybrid models and uncertainty quantification could enhance both accuracy and practical applicability in tribological systems.

.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Imran, M. & Khan, A. A. Characterization of Al-7075 metal matrix composites: a review. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 8 (3), 3347–3356 (2019).

Ramanathan, A., Krishnan, P. K. & Muraliraja, R. A review on the production of metal matrix composites through stir casting–Furnace design, properties, challenges, and research opportunities. J. Manuf. Process. 42, 213–245 (2019).

Kumar, K. R., Pridhar, T. & Balaji, V. S. Mechanical properties and characterization of zirconium oxide (ZrO2) and coconut shell Ash (CSA) reinforced aluminium (Al 6082) matrix hybrid composite. J. Alloys Compd. 765, 171–179 (2018).

Kumar, G. V., Rao, C. S. P. & Selvaraj, N. Studies on mechanical and dry sliding wear of Al6061–SiC composites. Compos. Part. B: Eng. 43 (3), 1185–1191 (2012).

Reddy, A. C. & Zitoun, E. Strengthening mechanisms and fracture behavior of 7072Al/Al2O3 metal matrix composites. Int. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. 3 (7), 6090–6100 (2011).

Saba, F., Sajjadi, S. A., Haddad-Sabzevar, M. & Zhang, F. Exploring the reinforcing effect of tic and CNT in dual-reinforced Al-matrix composites. Diam. Relat. Mater. 89, 180–189 (2018).

Liu, S., Wang, Y., Muthuramalingam, T. & Anbuchezhiyan, G. Effect of B4C and MOS2 reinforcement on micro structure and wear properties of aluminum hybrid composite for automotive applications. Compos. Part. B: Eng. 176, 107329 (2019).

em Pul, M., Calin, R. & Gül, F. Investigation of abrasion in Al–MgO metal matrix composites. Mater. Res. Bull. 60, 634–639 (2014).

Satyanarayana, T., Rao, P. S. & Krishna, M. G. Influence of wear parameters on friction performance of A356 aluminum–graphite/granite particles reinforced metal matrix hybrid composites. Heliyon, 5(6), e01770. (2019).

Singh, J. Fabrication characteristics and tribological behavior of al/sic/gr hybrid aluminum matrix composites: A review. Friction 4, 191–207 (2016).

Kumar, P. & Kumar, B. Synergistic approach to tribological characterization of hybrid aluminum metal matrix composites with ZrB2 and fly ash: Experimental and predictive insights. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part E: Journal of Process Mechanical Engineering, 09544089241255931. (2024).

Khawale, V. R. et al. Artificial neural network based prediction of specific wear rate in Al7475 composites reinforced with industrial wastes. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part C: Journal of Mechanical Engineering Science, 09544062251317118. (2025).

Kumar, S., Bera, S., Mandal, D. & Chakraborty, A. K. Transforming waste red mud and fly Ash to wealth by designing a hybrid al alloy composite with improved mechanical and tribological properties. Materialwiss. Werkstofftech. 56 (1), 122–131 (2025).

Kumar, D., Singh, P. K. & Saini, P. Morphological and mechanical characterization of the Al-4032/granite powder composites. J. Compos. Mater. 56 (15), 2433–2442 (2022).

Sekhar, R. A., Pillai, R. R., Ali, M. M. & Kumar, C. S. Enhanced mechanical and wear properties of aluminium-based composites reinforced with a unique blend of granite particles and Boron carbide for sustainable material recycling. J. Alloys Compd. 963, 171165 (2023).

Raj, R. & Thakur, D. G. Qualitative and quantitative assessment of microstructure in Al-B4C metal matrix composite processed by modified stir casting technique. Archives Civil Mech. Eng. 16 (4), 949–960 (2016).

Baradeswaran, A. E. P. A. & Perumal, A. E. Influence of B4C on the tribological and mechanical properties of al 7075–B4C composites. Compos. Part. B: Eng. 54, 146–152 (2013).

Gudipudi, S., Nagamuthu, S., Subbian, K. S. & Chilakalapalli, S. P. R. Enhanced mechanical properties of AA6061-B4C composites developed by a novel ultra-sonic assisted stir casting. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 23 (5), 1233–1243 (2020).

Hasan, M. S., Wong, T., Rohatgi, P. K. & Nosonovsky, M. Analysis of the friction and wear of graphene reinforced aluminum metal matrix composites using machine learning models. Tribol. Int. 170, 107527 (2022).

Sharma, V. K., Kumar, P., Akhai, S., Kumar, V. & Joshi, R. S. Analyzing the tribological and mechanical performance of Al-6061 with rare Earth oxides: an experimental analysis. Proc. Institution Mech. Eng. Part. E: J. Process. Mech. Eng. 238 (5), 2278–2292 (2024).

Li, S., Wang, X. & Barnard, A. S. Diverse Explanations from Data-Driven and Domain-Driven Perspectives in the Physical Sciences (Science and Technology, 2024).

Chen, Y., Zhang, S., Wen, Y., Lai, Z. & Liu, T. Prediction of material stability of two-dimensional semiconductors: an interpretable machine learning perspective. APL Mater. 12(9), 091120 (2024).

Ammisetti, D. K. & Kruthiventi, S. S. Experimental investigation of the influence of various wear parameters on the tribological characteristics of AZ91 hybrid composites and their machine learning modeling. J. Tribol. 146(5), 051704 (2024).

Sahu, M. K. & Sahu, R. K. Experimental investigation, modeling, and optimization of wear parameters of B4C and fly-ash reinforced aluminum hybrid composite. Front. Phys. 8, 219 (2020).

Pujari, R. et al. Artificial neural network based wear and tribological analysis of al 7010 alloy reinforced with nanoparticles of SIC for aerospace application. J. Mach. Comput. 3(4), 446–455 (2023).

Sauer, C. et al. Design of amorphous carbon coatings using Gaussian processes and advanced data visualization. Lubricants 10 (2), 22 (2022).

Alagarsamy, S. V. et al. Taguchi approach and decision tree algorithm for prediction of wear rate in zinc oxide-filled AA7075 matrix composites. Surf. Topogr. Metrol. Prop. 9 (3), 035005 (2021).

Peng, Y. et al. WP-DRnet: A novel wear particle detection and recognition network for automatic ferrograph image analysis. Tribol. Int. 151, 106379 (2020).

Prasanth, I. S. N. V. R., Jeevanandam, P., Selvaraju, P., Sathish, K., Hasane Ahammad,S. K., Sujatha, P., … Sasikumar, B. (2023). Study of Friction and Wear Behavior of Graphene-Reinforced AA7075 Nanocomposites by Machine Learning. Journal of Nanomaterials,2023(1), 5723730.

Bhaumik, S., Pathak, S. D., Dey, S. & Datta, S. Artificial intelligence based design of multiple friction modifiers dispersed castor oil and evaluating its tribological properties. Tribol. Int. 140, 105813 (2019).

Developers, S. K. L. scikit-learn: machine learning in Python. (2019).

Vapnik, V. N. The support vector method. In International conference on artificial neural networks (pp. 261–271). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. (1997), October.

Salman, H. A., Kalakech, A. & Steiti, A. Random forest algorithm overview. Babylon. J. Mach. Learn. 2024, 69–79 (2024).

Peterson, L. E. K-nearest neighbor. Scholarpedia 4 (2), 1883 (2009).

Okwu, M. O., Tartibu, L. K., Okwu, M. O. & Tartibu, L. K. Artificial neural network. Metaheuristic Optimization: nature-inspired Algorithms Swarm Comput. Intell. Theory Applications, Vol. 927, 133–145 (2021).

Ramón, A. et al. eXtreme gradient Boosting-based method to classify patients with COVID-19. J. Investig. Med. 70 (7), 1472–1480 (2022).

Gangwar, S., Dubey, N. K. & Pathak, V. K. Experimental investigation and multi-objective optimization of multiple mechanical characteristics for chemically treated Kenaf fibre reinforced epoxy composite using grey fuzzy logic. Proc. Institution Mech. Eng. Part. L: J. Materials: Des. Appl. 236 (1), 166–179 (2022).

Pazhouhanfar, Y. & Eghbali, B. Microstructural characterization and mechanical properties of TiB2 reinforced Al6061 matrix composites produced using stir casting process. Mater. Sci. Engineering: A. 710, 172–180 (2018).

Shirvanimoghaddam, K. et al. Effect of B4C, TiB2 and ZrSiO4 ceramic particles on mechanical properties of aluminium matrix composites: experimental investigation and predictive modelling. Ceram. Int. 42 (5), 6206–6220 (2016).

Milojević, S. & Stojanović, B. Determination of tribological properties of aluminum cylinder by application of Taguchi method and ANN-based model. J. Brazilian Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 40 (12), 571 (2018).

Zhao, M., Wu, G., Jiang, L. & Dou, Z. Friction and wear properties of TiB2P/Al composite. Compos. Part A: Appl. Sci. Manufac. 37 (11), 1916–1921 (2006).

Poria, S., Sahoo, P. & Sutradhar, G. Tribological characterization of stir-cast aluminium-TiB2 metal matrix composites. Silicon 8, 591–599 (2016).

Dipankar, D. E. Y., Bhowmik, A. & Biswas, A. Influence of TiB2 addition on friction and wear behaviour of Al2024-TiB2 ex-situ composites. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China. 31 (5), 1249–1261 (2021).