Abstract

The world faces ongoing challenges because the increasing number of dengue fever cases has become a major public health concern, with the potential for a pandemic resulting from a lack of attention and neglect. The Hajjah Governorate, located in subtropical regions, has not received any epidemiological studies on the prevalence of dengue fever. Therefore, we designed this study retrospectively to assess the prevalence of dengue fever in Hajjah Governorate over a five-year period (2020–2024). This retrospective study was based on secondary clinical data collected from the Hajjah Governorate Health and Environment Office database between 2020 and 2024. Furthermore, the data were obtained electronically, checked for their completeness and consistency, analyzed statistically, and presented in tables and figures. Of the 10,617 suspected dengue fever cases, 7,784 (73.3%) were classified as dengue fever according to the laboratory diagnosis (4,284; 40.3%) and clinical signs and symptoms (3,500; 33.0%). A higher proportion of DF cases was observed in males (6,994; 74.7%), the age group 5–14 years (1,632; 75.5%), in 2020 (3,756; 81.5%), and in autumn (3,625; 46.6%) and October (2,527; 32.5%). An overall incidence rate of dengue fever was reported at 28.1 cases per 10,000 individuals in Hajjah Governorate, with the highest in males (38.7), the age group of 15–29 years (40.0), in 2020 (16.3), and in Shars District (346.9). The rate of death related to dengue fever was 10 cases (0.13%), with the highest rates observed in males (0.13%), individuals under the age of 5 years (0.57%), and in 2023 (0.48%). The majority of patients experienced fever (99.97%), joint pain (99.1%), headache (98.8%), and muscle pain (73.3%). Additionally, 26 patients (0.03%) displayed symptoms of dengue hemorrhagic fever. These results indicate that the burden of dengue fever is increasing in the study area and poses a significant health challenge to Yemen in the near future if this complex health problem is not addressed. Furthermore, effective vector control, preventive education, targeted vaccination research, and epidemiological surveillance are imperative to address this complex health issue and to minimize its impact.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dengue fever (DF) is one of the most important mosquito-borne viral diseases that cause problems for the global health system and is endemic in large numbers in tropical and subtropical regions where the number of vector mosquitoes multiplies under favorable conditions1. Dengue virus is frequently transmitted to humans by the bite of an infected female Aedes mosquito, particularly Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus. This virus can be transmitted between individuals through blood transfusion and organ transplantation1,2. Moreover, a pregnant mother can transmit the dengue virus to her fetus during pregnancy through the placenta or through milk during breastfeeding3.

Symptoms of dengue fever are characterized with a high fever, headache, nausea, vomiting, and muscle and joint pains, and malaise, followed by a distinct measles-like rash. In addition, in a few cases, the disease progresses to life-threatening dengue hemorrhagic fever, resulting in bleeding, thrombocytopenia, and loss of blood plasma, where a dangerous drop in blood pressure occurs1,4.

Dengue fever is commonly prevalent in communities that suffer from a lack of resources, increasing rates of poverty, overcrowding, increased population migration and displacement, a lack of health services, and a lack of effective surveillance programs to control and monitoring the mosquito-borne diseases. Moreover, providing suitable environmental conditions, such as appropriate temperature and humidity, contributes greatly to the reproduction and increase of mosquitoes5.

Dengue fever, a global threat, increased from 30.67 million cases to 56.88 million between 1990 and 2019, an 85.47% increase. Furthermore, the number of deaths from dengue fever increased from 28,151 to 36,055 between 1990 and 20196,7. Globally, 6.43 million dengue cases and 6,892 dengue-related deaths were recorded in 2023, and 14 million cases and 10,000 deaths were recorded in 20248. Meanwhile, 1.4 million cases and 400 deaths were recorded in the 53 countries of the WHO Regions of the Americas from the beginning of 2025 until the end of March9.

Recently, a new dengue vaccine (TAK-003) received World Health Organization approval. This vaccine is a live attenuated, multivalent vaccine containing copies of all four serotypes of the dengue virus that causes dengue fever. According to the WHO, the TAK-003 vaccine is advised to be administered in two doses to children aged 6–16 in regions with a high dengue burden and high transmission intensity10.

In Yemen, the incidence of dengue fever increased by 600% between 2015, with 1,755 suspected cases, and 2019, with 11,900 suspected cases and approximately 25 deaths recorded in 201611. In addition, approximately 4,183 suspected cases of dengue fever were documented between the first and eighth weeks of 2019, with Al Hudaydah being the most affected governorate with 1,466 cases, followed by Aden with 1,064 cases, and Mukalla with 450 cases12. Furthermore, previous studies in Yemen recorded 630 confirmed cases of dengue fever in the Hadramaut governorate13 and 134 in the Taiz governorate14. Currently, a study conducted by Edrees et al.15. recorded approximately 104,562 dengue fever cases in the governorates of the southern part of Yemen between 2020 and 2024.

In recent times, Yemen has been facing environmental changes (such as climate, temperature, and humidity), population crises resulting from political and financial instability, and a 10-year-long war and blockade that has led to the fragility of the health system and the spread of epidemic diseases in most areas of Yemen16,17,18,19,20. Hajjah Governorate is among the governorates most affected by climate change, as the majority of its districts are located in the Tihama region, which is considered one of the hottest and most humid regions in Yemen. This makes it the most suitable environment for the proliferation of disease vectors such as malaria and dengue fever, and there is a lack of disease monitoring and surveillance programs.

This study aimed to shed light on a neglected epidemiological issue that has not received prior attention: the burden of dengue fever in Hajjah Governorate over a five-year period from 2020 to 2024. The results of this study will better contribute to filling the knowledge gap regarding the dengue outbreak in Hajjah Governorate and its most affected areas and will be useful in implementing control and prevention programs aimed at reducing the spread of this type of epidemic in an emergency.

Methods

Study area

Yemen is located in the southwestern part of the Arabian Peninsula in western Asia. Its area is approximately 555 thousand square kilometers, its population is 33 million, and it consists of 21 administrative governorates21. The governorate of Hajjah is located in the northwest of Yemen, and the distance from the Sana’a capital is approximately 123 km. To the north, it borders Saudi Arabia and the governorate of Al-Hudaydah; to the east, it borders the governorate of Amran; to the south, the governorate of Al Mahwit; and to the west, the Red Sea and parts of the governorate of Al Hudaydah. Hajjah has a total area of 8,227 km², with a total population of 2,782,000 inhabitants. The mountain highlands of Hajjah governorate experience a moderate summer climate and a cold winter, while the coastal areas experience a tropical climate, characterized by hot summers (May, June, and July) with moderate humidity and mild winters (November, December, and January). Furthermore, the governorate comprises 31 administratively defined districts, further subdivided into 3,798 villages.

Cases definition

Suspected cases were defined as those who had come from or lived in an area where dengue fever is endemic and had signs of severe fever for three days or more, accompanied by two of the following symptoms: nausea and vomiting, rash, pain, and aches and pains in various parts of the body19. A confirmed case was defined as a case that met the clinical description and was laboratory-confirmed by detection of IgG and IgM antibodies, detection of NS1 antigen, or detection by molecular techniques22.

Data collection and analysis

This study relied on secondary data on dengue fever recorded in the Hajjah Governorate Health Office database. The office team collected data from Hajjah Governorate’s districts during the years 2020–2024. Through an official letter from Hajjah University to the Health Office explaining the importance of this study, the data was obtained in an electronic file (Excel file). The relevant data for this study were extracted, reviewed, cleaned, and organized for easy analysis. The office team collected, sorted, and organized data regarding dengue fever across the districts of the Hajjah Governorate during the years 2020–2024. Data were collected from the public and private sectors, including 38 hospitals, 43 health centers, 25 health units, and 4 Rapid Response Teams. These facilities represent a significant portion of healthcare activity in Hajjah Governorate. In these facilities, suspected dengue fever cases are primarily identified based on clinical signs and symptoms22. In addition, diagnostic tests were performed to detect IgG and IgM antibodies and NS1 antigen to dengue virus in blood samples by rapid and ELISA tests according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Furthermore, the database comprised the subsequent variables: the epidemiological week number, the month and year of infection, the sex, the age group, the district name, the diagnostic technique employed, and the clinical characteristics. Based on the epidemiological surveillance system used by the Health Office’s Epidemiological Surveillance Department, age groups were split into six subgroups: < 5 years, 5–14 years, 15–29 years, 30–44 years, 45–59 years, and ≥ 60 years.

This study included all complete data on dengue fever cases among individuals residing in Hajjah Governorate during the study period. However, all cases among individuals not residing in Hajjah Governorate and whose information was incomplete or recorded before or after the study period were excluded from the analysis.

The incidence rate of the dengue fever onset per 10,000 individuals was intended by dividing the overall number of dengue cases by the entire duration of risk exposure, measured in person-years.

To determine the case fatality rate (CFR) of dengue cases, the total number of dengue-related deaths was divided by the total number of dengue cases. Furthermore, calculations were performed for the overall case fatality and overall incidence rates. The population size at risk served as the denominator for incidence rates.

The obtained data related to dengue fever were entered into the Statistical Package for Social Sciences, SPSS (Version 24, IBM®, USA) statistical software. Furthermore, descriptive analysis was used to analyze and present the data in various tables and figures to illustrate the trends in dengue fever prevalence over the study period. The chi-square test (χ²) was used to compare different variables, and Fisher’s exact test was used to compare between variables of sex, age group, and year of onset based on case fatality rates. A probability value (P) of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographic characteristics of the dengue cases

Between 2020 and 2024, 10,617 suspected cases of dengue fever in patients aged 0–90 years were reported; the mean (± SD) was 24.10 ± 15.035. Males accounted for the largest number of dengue cases, accounting for 6,994 (65.9%); those aged 15–29 years accounted for 4,352 (41.0%), and in 2020, 4611 (43.4%). Of the 10,617 suspected cases, 7,784 (73.3%) were classified as dengue fever based on laboratory diagnosis (4,284; 40.3%) and clinical diagnosis (3,500; 33%), whereas 2,833 (26.7%) were negative for laboratory tests (Table 1).

Furthermore, the frequency of dengue fever was significantly higher among males compared to females (74.7% vs. 70.6%) with a significant difference (χ2 = 26.662; P = 0.000). These results did not show significant differences (P = 0.481) between the prevalence of dengue fever according to age groups, as it was noted that the highest prevalence rate was recorded among the age group 5–14 years (75.5%) and the lowest rate observed among those aged 45–59 years (67.7%). Regarding the years of dengue fever infection, the highest prevalence rate was recorded in 2020 (3,756; 81.5%), and the lowest rate was in 2023 (209; 39.5%), with significant differences between the prevalence rates and years (χ2 = 672.814; P = 0.000), as summarized in Table (1).

Laboratory tests used to identify dengue fever

Of the 10,617 suspected dengue cases, 4,284 (40.3%) were confirmed by laboratory methods (RDT and ELISA tests) and 2,833 (26.7%) were negative for laboratory tests, while 3,500 (33.0%) cases were diagnosed as dengue fever based on the clinical signs and symptoms. Moreover, it is noted from Fig. 1 that the number of suspected cases that underwent laboratory diagnosis is small compared to the number of cases that did not. According to the rapid test, the positivity of anti-IgM, anti-IgG, and NS1 antigens was recorded in 403/699 (57.6%), 761/1434 (53.1%), and 3699/6209 (59.6%) cases, respectively. Additionally, ELISA revealed that anti-IgM was positive in 431/1584 (27.2%) cases and anti-IgG was positive in 39/56 (69.6%) cases.

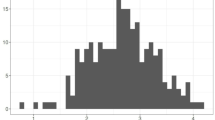

Trend of dengue fever by epidemiological weeks

Figure 2 indicates that weeks 42 and 43 in 2020 recorded a greater number of DF cases, with 569 and 449 cases, respectively, followed by week 49 in 2024 and week 46 in 2022, with 203 and 133 cases, respectively; week 03 in 2021, with 38 cases; and week 46 in 2023, with 18 cases.

Trend of dengue fever by seasons and months

This outcome revealed that a higher proportion of DF cases was recorded in autumn (46.6%, 3625 cases), followed by winter (40.6%, 3163 cases), summer (7.2%, 558 cases), and spring (5.6%, 438 cases). Furthermore, October recorded the majority of DF cases with 2527 cases (32.5%), followed by November with 1612 cases (20.7%), December with 1104 cases (14.2%), and September with 745 cases (9.6%), and June with 80 cases (1.0%) presented the lowest number of DF cases (Fig. 3).

Incidence rate of dengue fever

In this study, the Hajjah governorate recorded the overall incidence rate of DF at 28.1 per 10,000 individuals. Moreover, the study revealed a significantly higher incidence rate of DF in males compared to females (38.7 vs. 20.0). In addition, the age group of 15–29 years recorded the highest rate of DF incidence at 40.0 per 10,000 individuals, followed by 30–44 years (29.8 cases), 5–14 years (28.7 cases), ≥ 60 years (25.6 cases), and 45–59 years (20.3 cases), while the age group under five years had the lowest rate (14.4 cases). Furthermore, 2020 recorded a higher rate of FD incidence at 16.3 per 10,000 individuals, followed by 2022 with 7.6 cases per 10,000 individuals, 2024 with 5.2 cases, 2021 with 1.5 cases, and 2023 with 0.8 cases (Fig. 4).

These results showed that Sharas district recorded the highest incidence of dengue fever with 346.9 cases per 10,000 individuals, followed by Abs district with 127.5 cases per 10,000 populations, Aflah Al Yaman district with 58.7 cases per 10,000 individuals, and Bani Qais district with 44.4 cases per 10,000 inhabitants. Aslem, Mustaba, and Khayran Al Muharraq districts recorded 28.8, 15.7, and 12.4 cases per 10,000 inhabitants, respectively. Less than 8.5 cases per 10,000 individuals were recorded in Qafl Shamer and Ash Shaghadirah districts, while the remaining districts recorded fewer than 6 cases per 10,000 individuals (Fig. 5).

Case fatality rate of dengue fever

The total case fatality rate was 10 (0.13%) out of the 7,784 dengue fever cases recorded in Hajjah Governorate over a four-year period. The results showed no significant differences between the sex variables regarding case fatality rate (P = 0.360), with the highest rate recorded among males (7; 0.13%) compared to females (3; 0.12%). Additionally, the highest mortality rate was recorded among individuals under 5 years of age (3; 0.57%), followed by the age groups 45–59 years (1; 0.22%), 5–14 years (2; 0.13%), 30–44 years (2; 0.13%), and 15–29 years (2; 0.06%). No deaths were recorded among the age groups 60 years and older, with no significant differences between them (P = 0.059). Furthermore, the highest dengue fatality rate was in 2023 (1; 0.48%), and the lowest was in 2022 (1; 0.05%). There were no significant differences between the years and fatality rate (P-value = 0.981), as shown in Fig. 6.

Clinical features associated with dengue fever

Table 2 shows the clinical symptoms reported among patients with dengue fever. The majority of patients with dengue fever suffered from fever (99.9%), joint pain (99.1%), headache (98.8%), and muscle pain (72.5%). More than half of the dengue patients presented with eye redness (63.9%), and less than half presented with vomiting (45.2%), general weakness (42.1%), abdominal pain (28.0%), and skin rash (10.7%). Moreover, approximately 26 (0.3%) patients with dengue fever developed symptoms of dengue hemorrhagic fever (hematemesis, epistaxis, bleeding from the gums, blood in the urine, and stool).

Discussion

Many countries, particularly those in the developing world, are experiencing a substantial burden on their health systems as a result of the sudden rise in the number of dengue fever cases, which is attributed to climate, demographic, and environmental changes, as well as increased urbanization7,23. Yemen is considered one of the poor countries where dengue fever is endemic, according to previous studies11. This study showed that the rate of dengue fever cases in Hajjah Governorate reached 73.3% (7,784 cases) over five years. In the southern governorates of Yemen, a recent study documented 104,562 cases of dengue fever between 2020 and 202415. Moreover, according to previous reports from Yemen, the number of suspected dengue cases was 14,504 in 2015 and 59,486 in 201924,25. Furthermore, 281,698 cases of dengue were reported in Bangladesh in 2019 by Ashraf et al.26, 6.10 million cases were reported in China, and 27.99 million cases were reported in India by Du et al.6.

In this study, approximately one-third of the dengue cases were diagnosed based on clinical signs and symptoms, which can lead to misdiagnosis of dengue fever, indicating that the underdiagnosis of dengue cases in the study areas is low. Dengue, chikungunya, and Zika viruses are transmitted by female Aedes mosquitoes, as well as malaria, which is transmitted by female mosquitoes that are usually endemic to the same tropical and subtropical regions and cause similar symptoms in humans. More than one disease may occur simultaneously27,28. The low number of cases diagnosed in laboratories may be attributed to resource constraints and the unavailability of laboratory tests for dengue fever. In areas experiencing dengue outbreaks, health facilities must make greater efforts to provide laboratory-based testing equipment and train health workers to conduct tests correctly.

Furthermore, the positivity of the NS1 antigen was reported in this study at 59.6%, and this finding is lower than reported recently at 76.2% in Somalia by Jama et al.29 and 84.57% in Somaliland by Yosef et al.30. The low NS1 positivity rate in this study may be due to the fact that the majority of laboratory-diagnosed dengue cases were in the late stages of infection. Most Yemeni regions lack a comprehensive healthcare system that facilitates early diagnosis, leading to delays in the disease’s diagnosis. The NS1 antigen test is only useful for rapid detection of dengue fever in the early stages of infection (between 3 and 5 days), especially when the virus concentration in the blood is low and the immune system is unable to detect it due to a lack of IgM antibodies31,32,33.

This finding revealed that half and more than a third of dengue fever cases were recorded in the autumn and winter, respectively, while the lowest number was recorded in the spring. A recent study conducted in Yemen by Edrees et al.15 revealed that dengue fever cases increase significantly in the autumn and summer. Similar studies have documented that the highest number of dengue fever cases occurred during summer and winter29,33,34. Furthermore, previous reports indicate that mosquito populations and dengue fever incidence rates are strongly influenced by climate change and increased rainfall35,36.

The reason for the increase in the number of cases in Hajjah governorate during the autumn and winter is the geographical location of most of its districts, which extend into the Tihama region, which is characterized by a moderate climate and high humidity in the autumn and winter, which provides a suitable environment for the breeding of mosquitoes that transmit the dengue virus. Therefore, greater efforts should be made to monitor and control dengue virus vectors during peak dengue transmission seasons.

These data revealed that the overall incidence rate of DF in the Hajjah governorate was reported at 36.7 cases per 10,000 populations. This report is lower than reported in the governorates of Shabwah (176.96 cases), Abyan (160.1 cases), Taiz (131.93 cases), and Aden (115.97 cases)15. The discrepancy in results may be due to geographic location, the efficiency of dengue fever surveillance and monitoring systems, the efficiency of case documentation and reporting, diagnostic methods, the fact that some patients were treated in other governorates, and the misdiagnosis of dengue cases.

To address the complex health challenges posed by dengue and mitigate its impact, it is essential to adopt a “One Health” approach that provides a comprehensive, systematic, and sustainable means of preventing and controlling dengue37. This approach relies on collaboration and coordination across multiple disciplines, such as ecology, health sciences, climate sciences, technology, and management sciences, to implement an effective strategy aimed at achieving optimal health for humans, animals, and the environment38,39. This approach implements an effective dengue control strategy that includes several collaborative initiatives aimed at strengthening the ongoing epidemiological surveillance system, eliminating vector breeding sites, improving the health infrastructure, adopting preventive educational interventions, and improving environmental health37.

Furthermore, this study shown a significantly higher incidence rate of DF in males compared to females (49.92 vs. 27.06). This study agrees with a recent study conducted in Yemen by Edrees et al.15 and other countries34,40,41, and differs from the global report, which indicated a higher infection rate among females than males7. The reason for the disparity in infection rates between the sexes is due to religious and cultural factors in Yemen, which contributed to the lower infection rate among females in this study. Therefore, health strategies should focus on males who are most vulnerable, providing preventive and treatment programs tailored to meet their specific needs.

Regarding the age group, the age groups of 15–29 years and 30–44 years recorded the highest rate of DF incidence, while the age group under five years had the lowest rate. These results are completely in consonance with previous reports34,42,43, which also observed higher incidence rates among similar age groups. The prevalence of dengue fever among these age groups is due to their outdoor activities, particularly during peak mosquito activity that occurs before sunset and within two hours of sunrise. This consistency highlights the importance of focusing on these age groups and educating them about taking preventive measures to reduce exposure to mosquitoes, such as wearing protective clothing and using mosquito repellent, particularly in areas that are most affected by dengue fever.

These results indicated that the Hajjah governorate recorded the highest incidence of dengue fever in the years 2020 and 2022. This study is completely similar to the study conducted in Yemen by Edrees et al.15 as well as the report documenting global trends in dengue fever between 1990 and 2019 by Du et al.6. This increase in dengue fever cases is attributed to the COVID-19 pandemic that occurred between 2019 and 2022, which impacted the global health system and halted many disease surveillance and control programs in many countries, especially those with limited resources44. Therefore, health institutions must not neglect the continuation of disease surveillance and early detection programs, even in the event of a pandemic similar to COVID-19.

Regarding the incidence rate of infection by district, Sharas was classified as the most affected district in Hajjah Governorate by dengue fever, as it recorded three times the incidence rate compared to Abs district. Sharas District is characterized by high temperatures due to its location within Sharas Valley, a dumping ground for sewage and garbage from Hajjah City. Furthermore, Abs District is the largest district in the Tihama region, home to many disease vectors, such as dengue fever and malaria. Furthermore, Abs District is among the most active areas in the ongoing armed conflict since 2015, which has hampered medical supplies to the area and closed most health facilities, contributing to an increase in severe dengue fever cases. The local authority should focus on improving the environmental conditions in the Shars district by addressing the issue of sewage and proper waste disposal. Community members in the most affected areas should also be encouraged to play an active role in dengue prevention by adopting healthy practices, promoting preventive measures, and raising awareness among their families.

This analysis recorded 10 cases (0.13%) of dengue-related deaths, which is lower than the previous study in South Yemen Governorate, which recorded a total rate of 0.21%. The highest number of deaths from dengue fever was found in Aden Governorate (0.82%), followed by Lahj (0.41%) and Al Mahrah (0.38%)15. Previous reports from Yemen indicated that the case fatality rate from DF was 1.9% in Hadhramout between 2005 and 200913 and between 0.4 and 0.5% in 201912,25.

These results revealed no significant differences between the sex variables, with males having the highest rate in comparison to females. These findings align with global records, indicating a higher mortality rate among males compared to females7,45. However, these results are not consistent with a recent study conducted in Yemen by Edrees et al.14. In terms of the year of infection, the highest dengue fatality rate was in 2023, and the lowest was in 2022. In a similar report, the southern part of Yemen recorded the highest death rate in 202014. Globally, 9,508 deaths associated with dengue were documented, with a case fatality rate of 0.07%. The number of deaths in 2024 was 15 times higher in comparison to the number of deaths (n = 683) in 201446. A variety of clinical symptoms are frequently displayed by dengue patients47. This finding revealed that the majority of patients experienced fever (99.97%), joint pain (99.1%), headache (98.8%), and muscle pain (73.3%), and this is similar to investigations conducted in the Khayran Al Muharraq district48.

Strengths and limitations of the study

This study is the first to focus on a comprehensive assessment of the epidemiological situation of dengue fever in the Hajjah governorate, a gap that has been missed in many previous epidemiological studies. The results of this study will contribute to filling this critical gap and offer key perspectives on the current situation, contributing to the development of effective strategies to improve dengue control and prevention. This analysis was based on laboratory diagnostic data and clinical diagnosis based on clinical manifestations, which was considered one of its strengths.

Some limitations of this study are taken into consideration. This analysis is based on secondary data from governmental health offices, which may be incomplete or unreliable due to variations in data quality and case reporting across districts. Moreover, the data collected from the study area may be underestimated, and the actual burden of dengue may be greater than what is presented in this analysis. In addition, due to the lack of data on the dengue fever burden in two districts outside the control of the Sana’a government authorities, the epidemiology of dengue fever in Hajjah governorate cannot be accurately presented. Furthermore, this investigation was unsuccessful in determining the dengue virus serotype, which will significantly enhance its significance. The absence of biochemical parameters, such as white blood cell count, platelet count, hematocrit, liver enzymes, and evidence of leaking (ultrasound), is considered another shortcoming of this study. Additionally, this study was unable to assess knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding dengue prevalence, as well as environmental factors contributing to dengue outbreaks in the study area.

Conclusion

Dengue fever in Yemen in general, and Hajjah Governorate in particular, remains a major challenge for the health system, given the absence of a comprehensive strategy and control programs aimed at strengthening national early warning, surveillance, response systems, and epidemic preparedness. Males and individuals aged 15 to 44 years were observed to be more affected by dengue fever, with the most widespread outbreak documented in 2020. Shars and Abs districts are among the areas with the highest dengue endemicity. Consequently, the effective management of dengue outbreaks requires the promotion of global collaboration to research the development of a dengue fever vaccine and to ensure that the most affected communities have access to adequate dengue vaccine supplies. To accurately portray the situation of dengue fever in Hajjah Governorate, a thorough investigation is necessary to assess the epidemiology of the dengue fever in districts where epidemiological data are unavailable. Furthermore, it is important to conduct a molecular epidemiological study to determine the genotype of the dengue virus and its prevalence in the Hajjah Governorate and other Yemeni governorates. In addition, local health institutions should organize awareness campaigns to raise public awareness about dengue fever and the importance of taking precautions against dengue infection, as well as promote early diagnosis and train healthcare workers.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CDC:

-

Centers for disease control and prevention

- CFR:

-

Case fatality rate

- DF:

-

Dengue fever

- ELISA:

-

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- SPSS:

-

Statistical package for social sciences

- WHO:

-

World health organization

References

World Health Organization. Dengue and severe dengue, 23 April 2024. WHO, (2024). Available at https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dengue-and-severe-dengue

Gwee, S. X., St John, A. L., Gray, G. C. & Pang, J. Animals as potential reservoirs for dengue transmission: A systematic review. One Health. 12, 100216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.onehlt.2021.100216 (2021).

Barthel, A. et al. Breast milk as a possible route of vertical transmission of dengue virus? Clin. Infect. Dis. 57 (3), 415–417. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cit227 (2013).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dengue | CDC Yellow Book 2024. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1 May 2023. Archived from the original on 14 February 2024. Retrieved 14 August 2024.CDC, (2023).

Rahman, M. M. et al. Knowledge, attitude and practices towards dengue fever among slum dwellers: A case study in Dhaka city, Bangladesh. Int. J. Public. Health. 68, 1605364. https://doi.org/10.3389/ijph.2023.1605364 (2023).

Du, M., Jing, W., Liu, M. & Liu, J. The global trends and regional differences in incidence of dengue infection from 1990 to 2019: an analysis from the global burden of disease study 2019. Infect. Dis. Ther. 10 (3), 1625–1643. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-021-00470-2 (2021).

Ilic, I. & Ilic, M. Global patterns of trends in incidence and mortality of dengue, 1990–2019: an analysis based on the global burden of disease study. Medicina 60 (3), 425. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60030425 (2024).

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Dengue worldwide overview; Situation update, March 2025. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-and-data/monitoring/weekly-threats-reports (accessed on 27 April 2025).

Haider, N., Hasan, M. N., Onyango, J., Asaduzzaman, M. & Global, L. 2023 marks the worst year for dengue cases with millions infected and thousands of deaths reported. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 13, 100459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijregi.2024.100459 (2024).

World Health Organization. WHO prequalifies new dengue vaccine. 15 May 2024. Available at: https://www.who.int/news/item/15-05-2024-who-prequalifies-new-dengue-vaccine

Eha May. WHO scales up response to control dengue fever in Yemen. 31 World Health Organization - Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. (2016). https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/who-scales-up-response-to-worldwide-surge-in-dengue

Weekly Epidemiological Dengue fever in Yemen. Monitor ; 12(11). (2019). 1–2. https://applications.emro.who.int/docs/epi/2019/Epi_Monitor_2019_12_11.pdf?ua=1&ua=1

Bin Ghouth, A. S., Amarasinghe, A. & Letson, G. W. Dengue outbreak in hadramout, yemen, 2010: an epidemiological perspective. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 86, 1072–1076. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.2012.11-0723 (2012).

Abdullah, Q. Y., Al-Helali, M. F., Al-Mahbashi, A., Qaaed, S. T. & Edrees, W. H. Seroprevalence of dengue fever virus among suspected patients in Taiz Governorate-Yemen. UJPR 5 (5), 21–26. https://doi.org/10.22270/ujpr.v5i5.482 (2020).

Edrees, W. H. et al. Dengue fever in yemen: a five-year review, 2020–2024. BMC Infect. Dis. 25 (1), 28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-024-10429-6 (2025).

Ali, M. et al. Chaulagain RPand Lal N. Antifungal susceptibility pattern of Candida species isolated from pregnant women. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 14, 1434677. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2024.1434677 (2024).

Al-Hadheq, A. A., Nomaan, M. H. & Edrees, W. H. Seroprevalence of hepatitis A virus infections among schoolchildren in Amran governorate, Yemen. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 5819. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90525-y (2025).

Edrees, W. H., Al-Shehari, W. A., Al-Haddad, O. S., Al-Halani, A. A. & Alrahabi, L. M. Trend of measles outbreak in Yemen from January 2020 to August 2024. Int. J. Gen. Med. 18, 1203–1214. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJGM.S508189 (2025).

Al-Hammadi, S. et al. Prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) among patients with oral infections in sana’a City-Yemen. BMC Oral Health. 25 (1), 1047. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-025-06247-0 (2025).

Edrees, W. H. & Al-Shehari, W. A. A retrospective analysis of the malaria trend in Yemen over the sixteen-years, from 2006 to 2021. BMC Public. Health. 25 (1), 239. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-025-21466-4 (2025).

OCHA. Humanitarian data exchange, Yemen: humanitarian needs overview. https://data.humdata.org/dataset/yemen-humanitarian-needs-overview?

Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). Case definitions, clinical classification, and disease phases: Dengue, Chikungunya, and Zika.; Washington, D.C. (2023). https://www.paho.org/sites/default/files/2023-12/2023-cde-definiciones-caso-dengue-chik-zika.pdf

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Surveillance, threats and outbreaks of dengue fever. Available online: May (2025). https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/dengue-fever/surveillance (accessed on 10.

Qirbi, N. Dengue fever in yemen: A large-scale disease outbreak in the context of ongoing conflict. Al-Razi Univ. J. Med. Sci. 1 (1), 1–10 (2020).

Al-Eryani, S., Altahish, G. & Saeed, L. Evaluation of a Dengue surveillance control program, Yemen, Hodeiadah iproc. 2022;8(1):e36631 (2021). https://doi.org/10.2196/36631

Ashraf, S., Patwary, M. M. & Rodriguez-Morales, A. J. Demographic disparities in incidence and mortality rates of current dengue outbreak in Bangladesh. New. Microbes New. Infect. 56, 101207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nmni.2023.101207 (2023).

Beltrán-Silva, S. L., Chacón-Hernández, S. S., Moreno-Palacios, E. & Pereyra-Molina, J. Á. Clinical and differential diagnosis: dengue, Chikungunya and Zika. Rev. Med. Hosp. Gen. Méx. 81 (3), 146–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hgmx.2016.09.011 (2018).

Lim, A. et al. The overlapping global distribution of dengue, chikungunya, Zika and yellow fever. Nat. Commun. 16, 3418. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58609-5 (2025).

Jama, S. S. et al. Retrospective study on the dengue fever outbreak in Puntland state, Somalia. BMC Infect. Dis. 24 (1), 735. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-024-09552-1 (2024).

Yosef, D. K. et al. Epidemiology of dengue fever in somaliland: clinical features, and serological patterns from a retrospective study. BMC Infect. Dis. 25 (1), 179. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-025-10558-6 (2025).

Moi, M. L. et al. Detection of dengue virus nonstructural protein 1 (NS1) by using ELISA as a useful laboratory diagnostic method for dengue virus infection of international travelers. J. Travel Med. 20 (3), 185–193. https://doi.org/10.1111/jtm.12018 (2013).

Amorim, J. H., Alves, R. P. D. S., Boscardin, S. B. & De Souza Ferreira, L. C. The dengue virus non-structural 1 protein: risks and benefits. Virus Res. 181, 53–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virusres.2014.01.001 (2014).

Kholedi, A. A., Balubaid, O., Milaat, W., Kabbash, I. A. & Ibrahim, A. Factors associated with the spread of dengue fever in Jeddah governorate, Saudi Arabia. EMHJ-East Mediterr. Health J. 18 (1), 15–23. https://doi.org/10.26719/2012.18.1.15 (2012).

Al-Nefaie, H., Alsultan, A. & Abusaris, R. Temporal and Spatial patterns of dengue geographical distribution in jeddah, Saudi Arabia. J. Infect. Public. Health. 15 (9), 1025–1035. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2022.08.003 (2022).

Morales, I. et al. Seasonal distribution and Climatic correlates of dengue disease in dhaka, Bangladesh. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 94, 1359–1361. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.15-0846 (2016).

Al Awaidy, S. T. et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of patients with dengue fever in a recent outbreak in oman: A single center retrospective-cohort study. Oman Med. J. 37 (6), e452. https://doi.org/10.5001/omj.2023.57 (2022).

Procopio, A. C. et al. Integrated one health strategies in dengue. One Health. 18, 100684. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.onehlt.2024.100684 (2024).

Mohamed, A. The synergies between international health regulations and one health in safeguarding global health security. Sci. One Health. 3, 100078. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soh.2024.100078 (2024).

Danasekaran, R. & One Health A holistic approach to tackling global health issues. Indian J. Community Med. 49 (2), 260–263. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijcm.ijcm_521_23 (2024).

Kumar, A. et al. A retrospective study on laboratory profile and clinical parameters of dengue fever patients. Pak J. Med. Health Sci. 15 (11), 3356–3359. https://doi.org/10.53350/pjmhs2115113357 (2021).

Riccò, M., Peruzzi, S., Balzarini, F., Zaniboni, A. & Ranzieri, S. Dengue fever in italy: the eternal return of an emerging arboviral disease. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 7 (1), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed7010010 (2022).

Gutu, M. A. et al. Another dengue fever outbreak in Eastern Ethiopia—An emerging public health threat. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 15 (1), e0008992. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0008992 (2021).

Melebari, S. et al. The epidemiology and incidence of dengue in makkah, Saudi arabia, during 2017–2019. Saudi Med. J. 42 (11), 1173–1179. https://doi.org/10.15537/smj.2021.42.11.20210124 (2021).

Edrees, W. H., Abdullah, Q. Y., Al-Shehari, W. A., Alrahabi, L. M. & Khardesh, A. A. F. COVID-19 pandemic in Taiz governorate, yemen, between 2020 and 2023. BMC Infect. Dis. 24 (1), 739. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-024-09650-0 (2024).

Zhang, W. X. et al. Assessing the global dengue burden: incidence, mortality, and disability trends over three decades. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 19 (3), e0012932. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0012932 (2025).

Haider, N. et al. Global dengue epidemic worsens with record 14 million cases and 9,000 deaths reported in 2024. Int. J. Infect. Dis. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2025.107940 (2025).

Muller, D. A., Depelsenaire, A. C. & Young, P. R. Clinical and laboratory diagnosis of dengue virus infection. J. Infect. Dis. 215 (suppl_2), S89–S95. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiw649 (2017).

Edrees, W. H., Mogalli, N. M. & Alabdaly, K. W. Assessment of some clinical and laboratory profiles among dengue fever patients in Hajjah government, Yemen. UJPR 6 (2), 38–41. https://doi.org/10.22270/ujpr.v6i2.571 (2021).

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Edrees W and Al-Halani A conceived of the study, Al-Qadhi Y, Humaid A, and Al-Hadheq A collected the data, Alkhyat S, Al-Arnoot S, and Alrahabi L analyzed the data, and Abdullah Q, Al-Shehari W, and Edrees W prepared the original manuscript. All authors reviewed, revised, and approved the manuscript for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics statement and consent to participate

The Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Applied Science, Hajjah University, approved this study on December 19, 2024, with reference number (032). Through an official letter from the Faculty of Applied Science to the Health Office outlining the importance and objectives of this analysis, permission was granted to gather related data for this study. Moreover, this analysis is in accordance with the Helsinki Protocol and Yemeni legal legislation (Law No. 4/2009). Furthermore, owing to the retrospective nature of this study, direct human contact was not involved. Based on Yemeni law, the need for informed consent was waived by the Ministry of Health and Environment, which allows researchers to use the data for research and publication purposes. Additionally, the data were processed anonymously, and the identity and privacy of participants were safeguarded through the use of coding to collect data.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abdullah, Q.Y., Edrees, W.H., Alkhyat, S.H. et al. Epidemiology of dengue fever in Hajjah governorate, yemen, from 2020 to 2024. Sci Rep 15, 27998 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12606-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12606-2

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Serological and molecular detection of hepatitis C virus in Amran governorate, Yemen

BMC Infectious Diseases (2025)