Abstract

Patients with celiac disease are at risk of micronutrient deficiencies due to long-term inflammation of the small intestine. Therefore, our aim was to investigate the correlation between CeD and micronutrients. A cross-sectional study enrolled a total of 59 newly diagnosed celiac patients and 59 controls. Levels of 17 vitamins and 10 trace elements were measured. Symptoms, serum IgA anti-TG2 (tTG-IgA), BMI, albumin, hemoglobin, and Marsh classification were recorded. The levels of micronutrients were compared between cases and controls, and correlations between micronutrients and other factors were analyzed. Celiac patients had lower levels of BMI, albumin, hemoglobin, vitamins A, E, K2 (MK-7, MK-4), B6, and B7, as well as zinc, and higher levels of vitamin B3 and chromium than controls (p < 0.05). The deficiency rates of vitamins A, E, and K2 (MK-7) and the excess rate of vitamin B3 were significantly higher than in controls (p < 0.05). Vitamin C, iron and calcium levels were negatively correlated with Marsh classification, while vitamin D and E levels were negatively correlated with serum tTG-IgA levels (p < 0.05). The vitamin A level in classical patients was lower than in non-classical patients (p < 0.01). In conclusion, micronutrient imbalance is very common in celiac patients, including both deficiencies and excesses. Therefore, it is necessary to assess micronutrient levels in newly diagnosed celiac patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Celiac disease (CeD), also known as gluten enteropathy, is a chronic multi-organ autoimmune disorder affecting the small intestine that occurs in genetically susceptible adults and children. Genetically susceptible individuals carrying human leukocyte antigen (HLA) DQ2 or DQ8 constitute the primary affected population for CeD, with a population prevalence of approximately 1%1. The identified CeD cases may represent only the tip of the iceberg, as many patients remain undiagnosed due to atypical symptoms or insufficient diagnostic capabilities2. The diagnosis of CeD follows the World Gastroenterology Organization global guidelines: patients must demonstrate both positive serological antibodies (tTG-IgA > 20 IU/mL) and villous atrophy on small intestinal biopsy (Marsh grade ≥ 2 indicating villous atrophy). CeD patients develop intestinal malabsorption syndrome secondary to gluten-induced mucosal damage, typically presenting with gastrointestinal symptoms such as chronic diarrhea and abdominal distension3. Additionally, these patients frequently exhibit malabsorption of various nutrients, leading to anemia, weight loss, short stature, and other nutritional deficiency manifestations4. Currently, the only established treatment for this condition is strict adherence to a gluten-free diet (GFD).

Vitamins and trace elements constitute indispensable micronutrients that, despite being required in small quantities, play essential roles in normal human physiology. Imbalanced intake—whether excessive or deficient—can lead to physiological abnormalities or disease pathogenesis. Numerous studies have documented that CeD patients frequently exhibit malabsorption of various micronutrients, resulting in systemic nutritional imbalances5,6,7. These micronutrient disturbances not only impair recovery from intestinal inflammation but may also elevate the risk of disease-related complications, thereby further compromising patient health. Emerging evidence suggests that certain vitamins and trace elements may directly participate in CeD pathogenesis through their specific physiological functions8,9. Current research on nutritional status in CeD patients shows variable results, likely reflecting influences from environmental factors, dietary habits, and regional differences. This variability underscores the need for further investigation into micronutrient-CeD relationships. Notably, China’s Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, with its wheat-based diet and multi-ethnic population, presents unique research opportunities. Regional studies10,11 report a 2.53% CeD prevalence among individuals with gastrointestinal symptoms, with significantly higher detection rates in Kazakh and Uygur populations compared to Han Chinese. These geographic and demographic characteristics make Xinjiang an ideal setting for investigating micronutrient-CeD associations, with important implications for understanding the roles of vitamins in CeD pathogenesis, clinical management, and prognosis.

Methodology

Study design and population

This cross-sectional study included 59 patients with newly diagnosed CeD who were hospitalized in the Department of Gastroenterology of the People’s Hospital of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region from February 2024 to December 2024. They were classified as the CeD group and met the diagnostic criteria of the World Gastroenterology Organization Global Guidelines for CeD (2021 edition). The CeD group was matched 1:1 with 59 healthy controls who were hospitalized during the same period. Individuals in the control group were matched with those in the CeD group by age, gender, and ethnicity. Exclusion criteria included: (1) patients with diabetes mellitus, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or infectious diseases; (2) patients with cancer or hematological diseases; (3) patients with heart, liver, or kidney dysfunction; (4) patients who had taken vitamin or trace element supplements within 3 months prior to enrollment. We measured levels of vitamins and trace elements in both CeD patients and controls, and recorded body mass index (BMI), serum hemoglobin, albumin, and other general characteristics for all participants. For CeD patients, we additionally recorded serum tTG-IgA levels and Marsh classification. We compared levels of vitamins, trace elements, hemoglobin, albumin, and BMI between CeD patients and controls, and analyzed correlations between micronutrients and Marsh classification, serum tTG-IgA levels, clinical phenotype, and hemoglobin levels. The study was approved by the institutional ethics committee, and all procedures were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Diagnosis and classification of CeD

According to the World Gastroenterology Organization global guidelines for CeD, patients were enrolled if they had both positive serum tTG-IgA antibodies (> 20 IU/mL) and villous atrophy on small intestinal biopsy (Marsh grade ≥ 2). Based on clinical manifestations, CeD patients were divided into two clinical phenotypes: gastrointestinal symptoms and extra-intestinal symptoms. Marsh classification was assessed through duodenal biopsies showing tissue damage, with the main classification criteria detailed in Table 1.

Determination of vitamins and trace elements

Six milliliters of blood were collected from both the CeD group and control group. Vitamin and trace element levels were quantified using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS). The analyzed micronutrients included:

17 Vitamins:

Fat-soluble: A, D (25-OH-D2/D3), E, K1, K2 (MK-4, MK-7).

Water-soluble: B1, B2, B3 (niacin), B5 (pantothenic acid), B6, B7 (biotin), B9 (folate), B12, C.

10 trace elements: Iron (Fe), copper (Cu), zinc (Zn), selenium (Se), molybdenum (Mo), lead (Pb), magnesium (Mg), calcium (Ca), chromium (Cr), manganese (Mn).

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation (x̄ ± s). Between-group comparisons were performed using either paired t-tests (for normally distributed data) or Wilcoxon signed-rank tests (for non-parametric data). Categorical variables were analyzed using chi-square tests. Correlation analyses employed Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients. A two-tailed p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of CeD patients

Among 59 CeD patients, women were the majority, accounting for 80%. The mean BMI was 23.0 ± 5.7. The most common symptom was abdominal pain (53%), followed by nausea and vomiting (46%) and diarrhea (39%). Among them, 39% of the patients had consumption symptoms like diarrhea and were classified as classical CeD patients, while the remaining patients were classified as non-classical CeD patients. Marsh classification IIIc was the most common, accounting for 45.7%, as shown in Table 2.

Differences in macronutritional status and BMI between CeD patients and controls

The levels of BMI (p < 0.05), hemoglobin (p < 0.01), and albumin (p < 0.01) in CeD patients were significantly lower than those in the control group, and the difference was statistically significant, as shown in Table 3.

Differences in vitamin and trace element levels between CeD patients and healthy controls

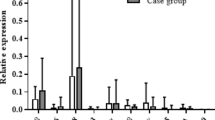

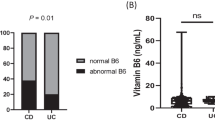

The levels of vitamins A, E, K2 (mk7), and B7 in CeD patients were significantly lower than those in healthy controls (p < 0.01). The levels of vitamin K2 (mk4), vitamin B6, and zinc were significantly lower than those of the control group (p < 0.05). Among them, the deficiency rates of vitamins A, E, and K2 (mk7) in CeD patients were significantly higher than those in the control group, respectively (86% vs. 66%, p < 0.05), (31% vs. 12%, p < 0.05), (27% vs. 5%, p < 0.01). While vitamin B3 (p < 0.05) and chromium level (p < 0.01) were significantly higher than those in healthy controls. The prevalence of vitamin B3 excess in CeD patients was significantly higher than that in controls (75% vs. 51%, p < 0.05). The remaining micronutrient levels were not significantly different from the control group, as shown in Tables 4 and 5.

Correlation analysis

Vitamin C (p < 0.05), iron (p < 0.01), and calcium (p < 0.01) were negatively correlated with Marsh classification. Vitamin D (p < 0.05) and E (p < 0.01) were negatively correlated with serum tTg-IgA levels, and there was no significant correlation between the remaining micronutrients with Marsh classification and tTg-IgA, as shown in Tables 6 and 7.

Differences in vitamin and trace element levels between CeD patients with gastrointestinal and extra-intestinal symptoms

Vitamin A levels were significantly lower in CeD patients with gastrointestinal symptoms compared to those with extra-intestinal manifestations. No significant differences were observed for other micronutrients between these two clinical presentations, as shown in Table 8.

Discussion

In CeD, the proximal small intestine is the most commonly affected segment, leading to impaired absorption of numerous nutrients, vitamins, and minerals. This malabsorption significantly compromises the nutritional status of CeD patients13. Characteristic complications include weight loss, growth retardation, and immune dysfunction resulting from chronic nutrient deficiencies4. Our findings corroborate these clinical observations, demonstrating significantly lower BMI, albumin, and hemoglobin levels in CeD patients compared to healthy controls.Through comprehensive analysis of 17 essential vitamins and 10 trace elements, we identified distinct micronutrient imbalances in CeD patients. While multiple vitamins and trace elements fell below both normal reference ranges and control group levels, we also observed significantly elevated levels of certain micronutrients compared to controls. These findings highlight the complex nutritional dysregulation in CeD that extends beyond simple deficiency states.

Vitamins are essential for maintaining normal physiological functions and metabolic processes in the human body. Since most vitamins must be obtained through dietary sources, patients with CeD frequently develop multiple vitamin deficiencies. Previous studies have documented altered vitamin status in CeD patients, demonstrating that malabsorption and dietary restrictions lead to decreased levels of several vitamins4,5,14. Research has consistently shown vitamin A deficiency in both children and adults at the time of CeD diagnosis6. Our study revealed an even more striking finding: 86% of adult CeD patients exhibited vitamin A deficiency, with levels significantly lower than those in healthy controls (p < 0.01). Additionally, we found that vitamin A levels were significantly lower in CeD patients with gastrointestinal symptoms than in those with extra-intestinal manifestations. Similarly, Imam MHet al.15 also demonstrated that the more severe the symptoms of diarrhea in patients with CeD, the lower their vitamin A levels, which is consistent with the results of our study. Our study also found lower vitamin E levels in CeD patients than control group, and the prevalence of vitamin E deficiency was significantly higher than that in the control group. Previous studies have also reached the same conclusion. Some researchers16,17 have pointed out that intestinal inflammation may cause obstacles to the absorption of vitamin E, while other studies18 have mentioned that oxidative stress plays an important role in the pathogenesis of CeD, which may lead to the aggravation of the consumption of vitamin E and other antioxidants and then cause their blood levels to decrease. Vitamin K exists in a variety of forms, the most critical of which are vitamin K1 and K2. Our study tested vitamin K1 and its two K2 forms (mk4, mk7) in CeD patients. The results showed that the levels of mk4 and mk7 in CeD patients were lower than those in the control group, and the deficiency rate of mk4 in CeD patients was significantly higher than that in the control group. As a coenzyme of the coagulation factorγ-carboxylase, vitamin K plays a crucial role in maintaining the normal coagulation function of the human body19. Previous case reports have indicated that CeD patients may have bleeding symptoms caused by vitamin K deficiency, including ecchymosis, hematuria, intramuscular hemorrhage and gross hematuria20. In addition, osteoporosis and decreased bone mineral density (BMD) are common complications of CeD. In recent years, the role of vitamin K in bone metabolism has attracted increasing attention, especially the role of vitamin K221. Mager et al.22 showed that vitamin K2 status impacts both BMD and bone accumulation in CeD patients. Therefore, we speculate that the deficiency of vitamin K in CeD patients may be one of the possible reasons for their decreased BMD. Many previous studies usually attributed the decrease of BMD in CeD patients to malabsorption of vitamin D and calcium23,24. However, our study found that the vitamin D and calcium levels in CeD patients were not significantly different from those in the control group, and the vitamin D deficiency rate was above 90% in both the CeD group and the control group. In view of the prevalence of serious vitamin D deficiency in this age group in this area, which may be related to environmental, dietary and cultural factors, there is no significant difference between CeD patients and patients with vitamin D deficiency. In addition, the study by Ahlawat et al.25 also reached the same conclusion and pointed out that this may be due to the high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in the study area.While CeD may exacerbate deficiency, our study design cannot fully disentangle disease-specific effects from environmental influences. This is one of the limitations of our research.

In addition to fat-soluble vitamins, we evaluated water-soluble B vitamins, which are commonly deficient in newly diagnosed CeD patients due to malabsorption and dietary restrictions26,27. Our study measured eight B vitamins and found significantly lower levels of vitamin B6 and B7 in CeD patients compared to controls, while vitamin B3 levels were significantly elevated. These results support previous research indicating that vitamin B6 deficiency in CeD contributes to hyperhomocysteinemia and increased cardiovascular risk14. In contrast, vitamin B7 and B3 status in CeD remain poorly characterized in existing literature. While neither CeD patients nor controls exhibited vitamin B7 deficiency, the control group demonstrated a higher prevalence of B7 excess, potentially explaining the relatively lower levels observed in CeD patients. Notably, both groups displayed elevated vitamin B3 levels, with CeD patients exhibiting significantly higher concentrations and a greater prevalence of excess compared to controls. This observation may reflect compensatory metabolic adaptations to chronic intestinal inflammation or alterations in gut microbial communities. The clinical implications of these findings warrant further investigation, particularly regarding the potential role of B3 excess in CeD pathophysiology and the need for B6 monitoring in clinical management. Vitamin B3 (niacin), a key mediator of inflammatory responses28, may be compensatively elevated in CeD patients due to chronic intestinal inflammation. This increase could reflect heightened metabolic demands for NAD + biosynthesis or altered gut microbial activity. The observation suggests vitamin B3 homeostasis may serve as a potential biomarker of disease progression in CeD. Zeidler et al.29 also demonstrated that vitamin B3 levels are compensatory increased under long-term inflammatory conditions, which may be a protective mechanism adopted by the body to cope with the metabolic demand caused by inflammation.

Newly diagnosed CeD patients are also usually combined with various trace element imbalances5,6,7. In our study, we observed that the levels of iron and zinc in CeD patients were significantly lower than those in control group. Previously conducted meta-analyses30 have pointed out that the prevalence of iron deficiency anemia in newly diagnosed CeD patients is between 12% and 82%, and even in some cases, iron deficiency anemia is the only clinical manifestation of CeD patients. Our study found that 8 CeD patients, or 13% of the total sample, had iron deficiency. In seven of these eight patients, hemoglobin levels were below the normal range, suggesting an anemic condition. Further correlation analysis showed that there was a significant positive correlation between the iron level and the hemoglobin level. We also found that iron elements showed a significant negative correlation with Marsh classification, which was consistent with the results of Javid et al.31. Thus, the present study reconfirms that the severity of intestinal inflammation in CeD patients is closely related to the degree of impaired iron absorption. Zinc is the most widely metabolized trace element in the human body and an important immunomodulator32. In our study, zinc deficiency was found in 12% of the adult patients, and its level was significantly lower than that of the control group. Previous studies33,34 have proved that intestinal inflammation in patients with CeD leads to zinc absorption disorders, and poor nutritional status of patients affects the absorption and utilization of zinc, resulting in a decrease in zinc levels in patients with CeD, which is consistent with the results of our study. Chromium is one of the essential trace heavy metals in the human body, which plays an important role in carbohydrate and lipid metabolism. However, excessive accumulation in the body may lead to heavy metal poisoning and even potential cancer risk35. Our study found that the chromium level in CeD patients was significantly higher than that in the control group, but it was maintained within the normal range. Kamycheva et al.36 found in their study on the correlation between CeD and heavy metals that children with CeD serum positivity showed low levels of heavy metals like blood lead and blood mercury, but adults did not show this correlation. Therefore, it is also important for CeD patients to evaluate their heavy metal element levels.

While our study primarily investigated micronutrient imbalances in adult CeD patients, it is noteworthy that pediatric populations may exhibit distinct nutritional profiles. Previous research by Tokgöz et al.37 highlights these differences in their analysis of fat-soluble vitamin levels among children with CeD. Compared to healthy controls, pediatric CeD patients demonstrated significantly higher deficiencies in vitamin A and vitamin D. Interestingly, however, no deficiencies in vitamin E or vitamin K1 were observed in this cohort. Additional research13 highlights that vitamin D, zinc, and iron deficiencies are particularly prevalent among newly diagnosed pediatric CeD patients. These disparities may reflect age-related variations in intestinal absorption, disease progression, or dietary intake patterns. Further comparative studies are needed to elucidate whether these differences stem from physiological factors or distinct pathophysiological mechanisms in pediatric versus adult CeD.

Conclusion

In summary, CeD is related to the imbalance of a variety of micronutrients. In addition to the decrease of macronutrient levels of albumin and hemoglobin, the levels of micronutrients such as vitamin A, E, K1, K2, B6, B7, iron, and zinc in CeD patients are significantly lower than those in the control group. The most likely reason is the malabsorption caused by the intestinal inflammatory response. The levels of vitamin B3 and chromium are higher than those of healthy people, which may be related to metabolic abnormalities or long-term intestinal inflammation in CeD patients. The decrease of vitamin A in patients with typical symptoms such as diarrhea was more significant than that in non-classical patients. Vitamin C, iron, and calcium were significantly correlated with the degree of intestinal tissue injury. Given these findings, we recommend prioritizing screening for the nutrients such as vitamins (A, E, K1,K2,B6,B7),iron and zinc in newly diagnosed CeD patients due to their higher malabsorption risk in CeD. Therefore, it is necessary to evaluate the levels of these key vitamins and trace elements in patients with newly diagnosed CeD to guide timely intervention and mitigate complications.

Limitations of the Study

While this study provides valuable insights into micronutrient imbalances in CeD patients, several limitations should be considered:

-

(1)

Selection Bias: The single-center recruitment design may limit the generalizability of our findings, as the study population may not fully represent the broader CeD demographic, including variations in dietary habits, disease severity, and comorbidities across different regions.

-

(2)

Reporting Bias: Dietary and supplement use data were self-reported, which may introduce inaccuracies due to recall bias or underreporting. Future studies could benefit from objective dietary assessments.

-

(3)

Assay Variability: Differences in laboratory methodologies for micronutrient quantification may affect result comparability with other studies. Standardized protocols would improve consistency in future research.

-

(4)

sample size : While our study provides insights into micronutrient deficiencies in CeD, we acknowledge the limited sample size (59 patients and controls) due to the disease’s low prevalence (~ 1% globally). This may affect statistical power and generalizability. Larger-scale confirmatory studies are needed for further evaluation.

Addressing these limitations in future multicenter studies with standardized assessments would strengthen the validity and applicability of the findings.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author or first author.

References

Catassi, C. et al. Coeliac disease. Lancet 399, 2413–2426 (2022).

Caio, G. et al. Celiac disease: A comprehensive current review. BMC Med.17, 142 (2019).

Sansotta, N., Amirikian, K., Guandalini, S. & Jericho, H. Celiac disease symptom resolution: Effectiveness of the gluten-free diet. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr.66, 48–52 (2018).

Mędza, A. & Szlagatys-Sidorkiewicz, A. Nutritional status and metabolism in celiac disease: Narrative review. J. Clin. Med.12, 5107 (2023).

Ben Houmich, T. & Admou, B. Celiac disease: Understandings in diagnostic, nutritional, and medicinal aspects. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 35, 20587384211008709 (2021).

McGrogan, L. et al. Micronutrient deficiencies in children with coeliac disease; a double-edged sword of both untreated disease and treatment with gluten-free diet. Clin. Nutr. 40, 2784–2790 (2021).

Wild, D., Robins, G. G., Burley, V. J. & Howdle, P. D. Evidence of high sugar intake, and low fibre and mineral intake, in the gluten-free diet. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther.32, 573–581 (2010).

Stenberg, P. & Roth, B. Zinc is the modulator of the calcium-dependent activation of post-translationally acting thiol-enzymes in autoimmune diseases. Med. Hypotheses. 84, 331–335 (2015).

DePaolo, R. W. et al. Co-adjuvant effects of retinoic acid and IL-15 induce inflammatory immunity to dietary antigens. Nature471, 220–24 (2011).

Yuan, J. et al. The tip of the Celiac iceberg in china: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 8, e81151 (2013).

Wang, M. et al. Epidemiological, clinical, and histological presentation of Celiac disease in Northwest China. World J. Gastroenterol. 28, 1272–1283 (2022).

Ludvigsson, J. F. et al. The Oslo definitions for coeliac disease and related terms. Gut 62, 43–52 (2013).

Erdem, T. et al. Vitamin and mineral deficiency in children newly diagnosed with Celiac disease. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 45, 833–836 (2015).

Hallert, C. et al. Evidence of poor vitamin status in coeliac patients on a gluten-free diet for 10 years. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 16, 1333–1339 (2002).

Imam, M. H., Ghazzawi, Y., Murray, J. A. & Absah, I. Is it necessary to assess for fat-soluble vitamin deficiencies in pediatric patients with newly diagnosed celiac disease?. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr.59, 225–228 (2014).

Hozyasz, K. K., Chelchowska, M. & Laskowska-Klita, T. Stezenia witaminy E u Chorych Na Celiakie [Vitamin E levels in patients with celiac disease]. Med. Wieku Rozwoj. 7, 593–604 (2003). Polish.

Piątek-Guziewicz, A. et al. Alterations in serum levels of selected markers of oxidative imbalance in adult Celiac patients with extraintestinal manifestations: a pilot study. Pol Arch. Intern. Med. 127, 532–539 (2017).

Piątek-Guziewicz, A. et al. Ferric reducing ability of plasma and assessment of selected plasma antioxidants in adults with Celiac disease. Folia Med. Cracov. 57, 13–26 (2017).

Mladěnka, P. et al. Vitamin K - Sources, physiological role, kinetics, deficiency, detection, therapeutic use, and toxicity. Nutr. Rev.80, 677–98 (2022).

Duetz, C., Houtenbos, I. & de Roij van Zuijdewijn, C. L. M. Macroscopic hematuria as presenting symptom of celiac disease. Neth. J. Med. 77, 84–85 (2019).

Tsugawa, N. & Shiraki, M. Vitamin K nutrition and bone health. Nutrients12, 1909 (2020).

Mager, D. R., Qiao, J. & Turner, J. Vitamin D and K status influences bone mineral density and bone accrual in children and adolescents with celiac disease. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr.66, 488–95 (2012).

Kondapalli, A. V. & Walker, M. D. Celiac disease and bone. Arch. Endocrinol. Metab. 66, 756–764 (2022).

Pritchard, L. et al. Prevalence of reduced bone mineral density in adults with coeliac disease - are we missing opportunities for detection in patients below 50 years of age? Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 53, 1433–1436 (2018).

Ahlawat, R., Weinstein, T., Markowitz, J., Kohn, N. & Pettei, M. J. Should we assess vitamin D status in pediatric patients with Celiac disease?? J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 69, 449–454 (2019).

Wierdsma, N. J., van Bokhorst-de, M. A., Berkenpas, M., Mulder, C. J. & van Bodegraven, A. A. Vitamin and mineral deficiencies are highly prevalent in newly diagnosed Celiac disease patients. Nutrients 5, 3975–3992 (2013).

Kemppainen, T. A. et al. Nutritional status of newly diagnosed Celiac disease patients before and after the institution of a Celiac disease diet–association with the grade of mucosal villous atrophy. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 67, 482–487 (1998).

Jacobson, M. K. & Jacobson, E. L. Vitamin B3 in health and disease: Toward the second century of discovery. Methods Mol. Biol.1813, 3–8 (2018).

Zeidler, J. D. et al. Endogenous metabolism in endothelial and immune cells generates most of the tissue vitamin B3 (nicotinamide). iScience 25, 105431 (2022).

Talarico, V. et al. Iron deficiency anemia in celiac disease. Nutrients13, 1695 (2021).

Javid, G. et al. Prevalence of celiac disease in adult patients with iron-deficiency anemia of obscure origin in Kashmir (India). Indian J. Gastroenterol.34, 314–19 (2015).

Sanna, A., Firinu, D., Zavattari, P. & Valera, P. Zinc status and autoimmunity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrientshttps://doi.org/10.3390/nu10010068 (2018).

Singhal, N., Alam, S., Sherwani, R. & Musarrat, J. Serum zinc levels in celiac disease. Indian Pediatr.45, 319–21 (2008).

Fathi, F. et al. The concentration of serum zinc in Celiac patients compared to healthy subjects in Tehran. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Bed Bench. 6, 92–95 (2013).

Vincent, J. B., Lukaski, H. C. & Chromium Adv. Nutr. ;9;505–506. (2018).

Kamycheva, E., Goto, T. & Camargo, C. A. Jr Blood levels of lead and mercury and Celiac disease seropositivity: the US National health and nutrition examination survey. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. Int. 24, 8385–8391 (2017).

Tokgöz, Y., Terlemez, S. & Karul, A. Fat soluble vitamin levels in children with newly diagnosed celiac disease, a case control study. BMC Pediatr.18(1), 130 (2018).

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC), Approval number :82260116 and Natural Science Foundation of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, Approval number:2022D01C831.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.N. and T.L. designed the study, collected and analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript.N.L. and T.S. contributed to the interpretation of the results.W.D.L. performed the statistical analysis and assisted in data collection.P.A. and K.A. reviewed the literature, provided critical feedback, and revised the manuscript.F.G. (corresponding author) supervised the project, secured funding, and finalized the manuscript for submission. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee of the People’s Hospital of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. Approval number: KY 2024013095; Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Patient consent statement

The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. The studiy approved by Ethics Committee of the People’s Hospital of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nuermaimaiti, K., Li, T., Li, N. et al. Vitamin and trace elements imbalance are very common in adult patients with newly diagnosed Celiac disease. Sci Rep 15, 28315 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12631-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12631-1