Abstract

The Tibetan Plateau (TP), characterized by its unique regional features and geographical landscape, is a critical area for studying changes in terrestrial water storage (TWS), which are significantly influenced by global warming. In this study, we integrate data from the Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) and the Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) to jointly estimate TWS variations in the TP and examine their spatiotemporal fluctuations in relation to large-scale climate patterns. To evaluate our approach, we conducted two synthetic tests, which showed that the root mean square errors (RMSEs) for the joint inversion were 23–37% lower than those for GNSS inversion, confirming the effectiveness of our method. When applied to real observational data, the joint inversion technique revealed that the spatial patterns and seasonal characteristics of TWS changes closely aligned with independent GRACE and Global Land Data Assimilation System (GLDAS) products, while offering more detailed insights into local hydrological processes. Notably, during the 2015/2016 El Niño event, the central and eastern TP experienced severe drought, primarily driven by precipitation anomalies (~ -150 mm) associated with extreme climate events, leading to a delayed hydrological response to the meteorological drought. Furthermore, we observed significant interannual variability across the TP sub-basins, with a moderate correlation with the El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO) at a one-month lag. Our research highlights the potential of joint inversion using GNSS and GRACE to enhance TWS monitoring in the TP, providing more spatially detailed insights into water storage variability in response to climate change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Terrestrial water storage (TWS) encompasses all forms of water both above and below the Earth’s surface, including surface water, snow, glaciers, soil moisture, and groundwater1. Variations in TWS reflect the balance between water inflow (e.g., precipitation, snowfall, and glacier retreat) and outflow (e.g., evapotranspiration and runoff), and provide insights into the hydrological cycle’s response to climate change2. Thus, a comprehensive analysis of TWS fluctuations offers valuable information for managing water resources, ensuring regional water security, and supporting ecosystem health3.

The Tibetan Plateau (TP, Fig. 1a) and its surrounding mountain ranges, including the Hindu Kush, Karakoram, and Himalayas, are often referred to as the “Third Pole” due to their vast frozen water stores, second only to the Polar regions. This region is also recognized as the Asian Water Tower (AWT), as it provides a significant portion of the water supply for nearly 2 billion people4,5,6. The TP is an ideal location for studying the effects of climate change on TWS variations, owing to its harsh environmental conditions that limit human activities2. Fluctuations in TWS play a crucial role in maintaining the regional water balance, with potential risks for extreme events such as flooding or drought, which significantly affect infiltration and baseflow processes. Additionally, under the influence of global climate change, the TP’s environmental conditions, ecosystems, and hydrological systems have experienced notable changes. Therefore, understanding TWS and water balance in the TP is critical for forecasting regional water availability under future climate scenarios7.

Due to the harsh environmental conditions of the TP, in-situ gauge-based measurements are labor-intensive and inadequate for accurately monitoring total TWS changes, as they can only capture individual TWS components. Furthermore, hydrological models often carry significant uncertainties due to limitations in input data and simplified physical assumptions8. Recent advancements in satellite geodetic observation technologies, particularly the Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) and its successor, GRACE Follow-On (GRACE-FO, hereinafter referred to as GRACE, unless specifically mentioning GRACE-FO), have significantly enhanced our understanding of TWS variations in the TP9,10,11,12.

Compared to in-situ gauge-based measurements and hydrological models, satellite-based observations provide new insights into TWS changes over large regions. GRACE-based studies in the TP have primarily focused on individual water storage components, such as glaciers9,13lakes14,15and groundwater16,17. However, GRACE’s coarse spatial resolution limits its ability to detect short-wavelength TWS changes18,19,20. As an alternative, the Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) offers high sensitivity to small-scale mass changes21but the spatial resolution of GNSS-derived TWS estimates is largely constrained by the density and distribution of GNSS stations22]– [23.

To address the limitations of GRACE’s coarse spatial resolution and the sparse distribution of GNSS stations, researchers have developed a joint inversion approach that combines the strengths of both geodetic techniques for hydrological applications. This includes methods applied in both the spatial domain24,25,26,27,28,29,30 and the spectral domain24,31. The objective of this study is to obtain more accurate and reliable estimates of TWS change over the TP by utilizing the joint inversion of GNSS and GRACE data, and to thoroughly investigate the seasonal and interannual variations in TWS, as well as its response to extreme climate events. This will provide valuable insights for the dynamic analysis of water resources in the TP.

(a) The boundaries of the TP and its 12 sub-basins, with red dots marking the locations of GNSS stations. The grey and pink solid lines represent the boundary and extended boundary of the TP, respectively. (b) The annual precipitation cycle for the entire TP from 2010 to 2021, averaged from two ERA5 and GPM precipitation datasets. (c) The annual temperature cycle for the entire TP from 2010 to 2021, averaged from two ERA5 and GHCN_CAMS temperature datasets. Graphs are created in Generic Mapping Tools (version 6.0.0) software32.

Study region and datasets

Study region

The TP, located in southwestern China between 26°N-40°N and 73°E-105°E, spans over 2.6 million square kilometers, with an average elevation exceeding 4,000 m. Its high altitude and unique climate system make it a critical region for studying hydrological processes and energy cycles, especially in the context of global climate change2. The TP’s water cycle is closely linked to large-scale atmospheric circulation and several monsoon systems, including the East Asian summer monsoon, Indian summer monsoon, and westerly circulation4. It exhibits clear seasonal contrasts, with dry months from November to May and wet months from April to October (Fig. 1b and c). In recent decades, the TP has experienced significant warming, disrupting the balance of terrestrial water cycle processes33,34. To analyze regional variations in TWS in response to climate change, we divided the TP into 12 sub-regions based on climate and geographical similarities (Fig. 1a). Detailed information about these sub-regions is provided in Table S16,14.

Datasets

This study incorporates various satellite observations and model assimilation data, with their spatiotemporal characteristics summarized in Table 1.

GNSS data and post-processing

We utilized continuous observations from 144 GNSS stations, which are part of the Crustal Movement Observation Network of China (CMONOC), Nevada Geodetic Laboratory (NGL), and Myanmar-India-Bangladesh-Bhutan (MIBB) networks35,36as shown in Figs. 1a and S1. Following the methodology of previous studies12,37the datasets were processed using GipsyX 1.0 software38 and referenced to the IGS14 reference frame39. Specifically, the Vienna Mapping Function (VMF) prior model was applied to correct for tropospheric effects, considering only the first- and second-order ionospheric corrections. Additionally, we employed the FES2004 model, which incorporates the elastic Green’s function finite element solution, to account for ocean tide loading40. Solid Earth and pole tides were removed using the International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service (IERS) model published in 201041.

In this study, we focused solely on the vertical displacements from GNSS stations, as the effect of hydrological load variations on vertical displacements is 2–3 times larger than its impact on horizontal displacements42,43. Due to the influence of both natural factors and human activities, the GNSS displacement time series contains outliers, offsets, data gaps, and high-frequency noise. Therefore, additional post-processing is required to ensure the reliability and continuity of the time series before estimating TWS changes. We employed the TSAnalyzer software developed by Wu et al. (2018)44based on the L1 regularization model, to eliminate outliers and offsets from the time series. To isolate the “clean” vertical displacements associated with hydrological load changes, we removed the displacements caused by non-tidal atmospheric loading (NTAL) and non-tidal oceanic loading (NTOL) effects using geophysical fluid loading products calculated in the center of surface figure (CF) reference frame, provided by the Earth System Modeling Group at the Deutsches GeoForschungsZentrum (ESMGFZ) (data available at https://rz-vm115.gfz-potsdam.de:8080/repository)45. As shown in Figure S2, the annual amplitudes of NTAL in the TP range from 1.5 to 4.5 mm, while the annual amplitudes of NTOL remain below 0.3 mm.

We estimated the thermoelastic deformation of GNSS stations in the TP using ERA5 daily surface temperature data, based on the model by Yan et al. (2009)46 (see Figure S3). Seasonal surface temperature variations resulted in a maximum deformation of only 0.17 mm, and due to uncertainties in the thermoelastic model, no corrections were applied. Additionally, we modeled load displacements of GNSS stations caused by hydrological mass changes outside the study area using the average of three GRACE mascon solutions and Green’s function (see Figure S4), with necessary corrections applied. These external hydrological mass changes have minimal impact on the displacements of GNSS stations within the region. To address missing data and high-frequency noise in the inversion process, we utilized the MATLAB-based “GNSS Missing Data Interpolation Software (GMIS)” developed by Liu et al. (2017)47employing the Kriging Kalman Filter (KKF) dynamic spatiotemporal model. Figure S5 demonstrates the effectiveness of this post-processing method in filling missing data and removing high-frequency noise from time series of two GNSS stations. Finally, we detrended the GNSS vertical displacement time series to eliminate any potential linear trends caused by glacial isostatic adjustment (GIA) and tectonic motion20,30,31,48. To match the temporal resolution of the GRACE data (monthly intervals), we averaged the daily GNSS vertical displacement time series to monthly values.

GRACE Mascon data

The GRACE satellite gravimetry mission has been crucial in advancing the study of spatiotemporal changes in TWS1,10. In this research, we utilize three available GRACE mascon solutions to quantify TWS variations in the TP49,50,51specifically from the Center for Space Research (CSR) at the University of Texas, the Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC), and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). To ensure continuity in TWS changes over the study period, we apply the singular spectrum analysis (SSA) method52 in the spatial domain to fill in the missing months within the GRACE data as well as the 1-year gap between GRACE and GRACE-FO. Furthermore, we calculate the vertical displacements induced by the GRACE mascon solutions and compare the resulting displacement amplitudes, averaged across the three displacement results, with those derived from GNSS measurements.

We used the three GRACE mascon solutions (CSR, JPL, and GSFC) and their average to calculate the spatial patterns of long-term trends, annual amplitudes, and phases of TWS in the TP, based on GRACE mascon data from April 2002 to December 2021, as shown in Figure S6. Figure S7 presents the monthly average time series of TWS for the entire TP and its annual cycle. The results from the three mascon solutions are highly consistent, indicating that the TWS change estimates are reliable. Spatially, regions with a decreasing TWS trend are primarily found in the high mountain glacier areas along the southern edge of Tibet, while inland areas, such as the Sichuan Basin and Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau, exhibit an increasing trend. This is largely attributed to glacier melting driven by global warming, which increases lake water storage and regional rainfall12,53,54. Additionally, due to regional precipitation patterns and the monsoon influence4,55,56the northwest and southern regions of Tibet exhibit larger annual variations in TWS, with significant spatial differences in the annual phase. As shown in Figure S7a, the overall TWS in the TP exhibits a downward trend, reaching its minimum during the 2015/2016 El Niño event, which indicates a severe drought during that period12. Moreover, the annual cycle of TWS, shown in Figure S7b, reveals that the peak TWS occurs between July and September, while the lowest water volume is observed from December to January.

GLDAS data

The Global Land Data Assimilation System (GLDAS) model was developed through collaboration between NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC) and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) National Environmental Prediction Center (NECP). We compare the monthly EWH products from GLDAS (i.e., the sum of snow water, soil moisture in the 0–200 mm layer, and canopy water) with the results of our joint inversion. These GLDAS estimates are also used as input signals for synthetic testing. It is important to note that GLDAS estimates do not account for certain surface water bodies, such as lakes, nor do they include groundwater.

Hydrometeorological data

To account for potential variability across datasets, we estimate each variable using two independent datasets and use their average as the final estimate. This approach helps mitigate systematic biases that may arise from relying on a single dataset57. Specifically, we use the fifth-generation European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) global climate atmospheric reanalysis dataset (hereinafter referred to as ERA5), published by the ECMWF58along with the Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) model dataset provided by NASA59 to identify precipitation. Furthermore, to explore the relationship between climate events and TWS changes, we employ the second version of the multivariate El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO) index (MEI) to capture the interannual responses of global climate. The MEI is a multivariate index derived from six variables using principal component analysis. Its response is not solely based on sea surface temperature, allowing it effectively capture the characteristics of both types of El Niño events60.

Methods

Forward modeling

The solid Earth undergoes elastic deformation in response to surface mass changes61with vertical displacement highly sensitive to the distance from the load source’s center. This sensitivity allows for high-resolution mapping of surface mass load distributions21. The study area is divided into a series of grids, each approximated by a disk element. The radius of each disk is determined to match the area of its corresponding grid cell, as equal-area disks more accurately represent the spatial information of each grid62. According to Wahr et al. (2013)42the vertical surface displacement caused by mass loading from the disks can be expressed as:

where hn represents the vertical load Love number derived by Wang et al. (2012)63 based on the Preliminary Reference Earth Model (PREM) Earth model64G is the gravitational constant, R is the Earth’s radius, g is the gravity acceleration, Pn is the Legendre polynomial, θ is the angular distance, and the specific form of the Γn function is provided by Wahr et al. (2013)42. Notably, due to the complex crustal structure of the TP65we use GNSS inversion to illustrate the impact of the Earth model on the results. Specifically, we employ the load Love numbers from the PREMhard model proposed by Wang et al. (2012)63in which the crustal structure is defined by Crust 2.0, incorporating hard sediments as the outermost layers. Figure S8 presents the spatial distribution of annual TWS amplitude obtained through GNSS inversion using both the PREM and PREMhard models. The results are nearly identical, as shown by the minimal differences in Figure S8c. Previous studies26,28,30,66 have also noted that location-specific elastic structures provide only marginal improvements in the vertical component between GNSS and GRACE, supporting the use of the simpler PREM model. Zhu et al. (2023)28 and Chen et al. (2024)30 focused on the southeastern TP, while Chanard et al. (2014)66 investigated the Himalayan region. Additionally, Carlson et al. (2022)26 reached similar conclusions, despite focusing on California. Therefore, consistent with prior studies, we adopt the PREM model for inversion in this study.

For the N GNSS stations and M disk loads within the region, we can derive:

where u=[u1,u2,···,uN]T represents the vertical displacement at N GNSS stations, h=[h1,h2,···,hM]T denotes the EWH values at M discs, and SN×M represents the Green’s function between the j-th (j = 1,2,···,M) disc and the i-th (i = 1,2,···,N) GNSS station.

Joint inversion method to estimate TWS variations

In this study, we inverted TWS variations on a 0.5°×0.5° grid across the TP using GNSS vertical displacement time series. The study area was divided into several grids, each represented by a circular unit. To accurately capture the information of each grid, we calculated the radius of the circle with an area equal to that of the grid cell (i.e., the radius of the disc is 31.4 km), avoiding the use of inscribed or circumscribed circles, as shown in Figure S9. To minimize edge effects, including significant mass losses surrounding the TP such as groundwater depletion and glacier melt in India, a 2.0° expansion was applied to all sides48. We then used the GRACE mascon results (i.e., the JPL mascon solution) to constrain the GNSS deformation inversion for TWS variations in the TP. Following Carlson et al. (2022)26we employed the EWH values from the 3° equal-area spherical cap of JPL mascon (shown in Fig. 2a), expressed as follows:

where MJPL represents the JPL mascon values provided on a 0.5° grid, and AJPL is the averaging operator that sums and averages the EWH values constrained by each 3° equal-area spherical cap of the JPL mascon.

The purpose of the joint inversion is to constrain the GNSS deformation inversion using the spatial resolution of the JPL mascon (approximately 3° resolution). By combining Eqs. (2) and (3), the observation equation for the joint inversion is given as follows:

where d=[u AJPLMJPL]T represents the observation vector for the joint inversion, while G=[S AJPL]T denotes the design matrix for the joint inversion. To ensure smooth variations in the optimal fitting solution across adjacent grids and boundaries, we apply the Laplace constraint, as shown below67,68:

where L represents the Laplacian smoothing matrix, with L2, L3, and L4 corresponding to the Laplacian operator templates for grid mass located at the corners, edges, and other regions, respectively. Additionally, β denotes the smoothing factor.

Due to the differing spatial sensitivities of GNSS and GRACE observations, GNSS data are more sensitive to short-wavelength signals at local scales, while GRACE data are more responsive to long-wavelength signals at larger scales69,70,71. Consequently, we apply weighting factors to adjust the relative contributions of GNSS and GRACE observations, leading to the following joint inversion formula:

where α represents the weighting factor, and (W(α2))–1 denotes the observation weighting matrix, defined as follows:

where the variance matrix σ2 GNSS for the GNSS observations and σ2 JPL for the JPL observations are both defined as identity matrices30,43 (see more details in Text S1).

From Eqs. (7) and (8), it is clear that determining the optimal weighting factor α and smoothing factor β is crucial for accurate joint inversion estimation. For instance, a high α may lead to overfitting of the JPL observations while significantly deviating from the GNSS observations, thereby reducing the spatial resolution. Conversely, a low α may cause the opposite effect. Similarly, a high β value may cause excessive smoothing, while a low β may have the opposite effect. In this study, we utilize the ABIC criterion72]– [73 to determine the optimal values for α and β, as outlined below:

where n represents the number of observations, and ||·|| denotes the product of the non-zero eigenvalues of the matrix.

The optimal weighting factor α and smoothing factor β are determined when the ABIC reaches its minimum. Figure 2b shows the distribution of ABIC values for September 2010, with color coding representing the magnitude of the ABIC values. The optimal solution occurs at log(α2) = 2 and log(β2) = -5.

(a) The boundary of the 3° equal-area spherical cap for the JPL mascon in the TP, with the rectangular borders representing the 3° equal-area cap, and the gray and pink solid lines indicating the boundaries and extended boundaries of the TP, respectively. (b) The distribution of ABIC values from the joint inversion, where the red dot marks the optimal parameters corresponding to the minimum ABIC. Graphs are created in MATLAB R2020b software (https://ww2.mathworks.cn/products/new_products/release2020b.html).

Synthetic tests of joint inversion method

To evaluate the theoretical feasibility, sensitivity, and robustness of the joint inversion, we designed two synthetic experiments: one based on a checkerboard model and the other on a more realistic hydrological mass model, which was constructed using the annual amplitude of the GLDAS model as the reference for true EWH values.

Synthetic checkerboard model

In this study, we evaluate the feasibility and spatial resolution of joint inversion using checkerboard patterns with grid spacings of 3°×3° and 3.5°×3.5° (Fig. 3). First, the true EWH values from the checkerboard model are forward-modeled into vertical displacements at GNSS stations based on Eq. (2), simulating the GNSS observations. Next, average EWH grid values within the 3° equal-area spherical caps of the JPL mascon in the TP are employed as constraints. To enhance the simulation’s accuracy, white Gaussian noise with standard deviations of 0.8 mm and 15 mm is added to the GNSS and GRACE data, respectively43. Finally, EWH estimates are obtained through both GNSS and joint inversion methods.

The GNSS inversion (Fig. 3a and c) effectively recovers checkerboard patterns in the Himalayas, Sichuan Basin, and Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau, as shown by the checkerboard test at a 3.5°×3.5° grid spacing. However, due to the sparse distribution of GNSS stations in the northwest and inner TP, recovering checkerboard patterns in these regions proves challenging. In contrast, incorporating GRACE observations within the joint inversion framework significantly improves the GNSS inversion results (Fig. 3e), particularly in areas with fewer GNSS stations. As a result, the root mean square error (RMSE) of the joint inversion is reduced by 23% compared to the GNSS inversion, highlighting the advantages and effectiveness of the joint inversion approach. To assess the spatial resolution of the joint inversion, we also utilize a checkerboard with a 3°×3° grid spacing. As shown in Fig. 3b and d, the joint inversion method more accurately recovers the spatial patterns in regions with dense GNSS station coverage (e.g., Himalayas, Sichuan Basin, and Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau), although recovery in the northwest and inner TP remains suboptimal. It is important to note that the spatial resolution of TWS changes derived from actual GNSS observations will be lower than those indicated by the checkerboard tests, due to inherent errors in the GNSS data.

Results from the synthetic checkerboard model. (a) The true EWH values derived from the synthetic input with a 3.5°×3.5° grid spacing. (c,e) The EWH estimates from GNSS and joint inversion, respectively, using the 3.5°×3.5° grid spacing. (b) The true EWH values from the synthetic input with a 3°×3° grid spacing. (d) The EWH estimates from the joint inversion with a 3°×3° grid spacing. The green dots represent the spatial locations of GNSS stations, while the black and white grids indicate EWH values of 300 mm and 0 mm, respectively. Graphs are created in MATLAB R2020b software (https://ww2.mathworks.cn/products/new_products/release2020b.html).

Synthetic GLDAS model

Given the unrealistic nature of the checkerboard model in representing actual hydrological mass changes, we developed an alternative hydrological mass dataset based on the GLDAS model. Specifically, the input EWH values are derived from the annual amplitudes of the GLDAS model (Fig. 4a), with the remaining procedures following the steps as outlined in “Synthetic checkerboard model”. Figure 4 presents the results of the synthetic test using the GLDAS model. Comparing the RMSE values in Fig. 4b and c, the joint inversion reduces the RMSE by 37% relative to the GNSS inversion. These results demonstrate that the joint inversion method more effectively recovers TWS changes in the TP, particularly in the northwest and inner TP regions, where GNSS station coverage is sparse. This conclusion aligns with the results from the checkerboard model and further highlights the advantages and reliability of the joint inversion approach presented in this study.

Results from the synthetic GLDAS model experiment. (a) The true EWH values derived from the synthetic input. (b)-(c) The EWH estimates obtained from GNSS and joint inversion, respectively. The pink dots indicate the spatial locations of GNSS stations. Graphs are created in Generic Mapping Tools (version 6.0.0) software32.

Implementation of TWS inversion in the TP

After validating the joint inversion method through synthetic tests, we applied it to the inversion of real GNSS coordinate time series data for the TP, covering the period from August 2010 to December 2021.

Seasonal vertical surface motions

GNSS provides highly accurate measurements of vertical movements of the Earth’s surface in response to water load, with millimeter-level precision23,74. By utilizing three different data sources, including direct GNSS observations (after removing the non-tidal atmospheric and oceanic load effects) and model predictions from GRACE and GLDAS, we compared the vertical crustal displacements (VCD) induced by hydrological mass changes at GNSS stations across the TP. Figure 5 presents the annual VCD amplitudes estimated from these three datasets using least squares regression, along with a linear regression comparison. The results show that the annual amplitudes are larger in the Himalayas and the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau, which aligns with the spatial distribution of annual amplitudes observed in the GRACE data (Figure S6k). The amplitude ranking across datasets is GNSS > GRACE > GLDAS, reflecting differences in their spatial resolution and processing methodologies48. Additionally, we randomly selected nine GNSS stations to illustrate individual results in Figure S10. It is important to note that the long-term trends associated with crustal deformation and GIA were removed from the data75. The temporal variation patterns of GNSS displacements largely correspond to the hydrological load deformation derived from GRACE and GLDAS. However, GNSS signals are generally more pronounced, likely due to the sensitivity of GNSS data to local and regional hydrological signals, whereas GRACE provides a more generalized estimate of TWS changes. Furthermore, the GLDAS model tends to underestimate water content, as its representation of the water/energy cycle is limited8,21,23.

The annual amplitudes of VCD derived from different datasets across the TP. (a-c) Represent the annual amplitude and phase of VCD based on GNSS, GRACE, and GLDAS, respectively. The radius of each circle represents the annual amplitude, while the color of the circle indicates the day of year when the maximum value occurs. (d-f) Present linear regression comparisons of the annual VCD amplitudes derived from these datasets, with green solid lines representing the fitted regression line and black dashed lines indicating the ideal “slope = 1” scenario. Graphs are created in Generic Mapping Tools (version 6.0.0) software32.

Spatial distribution of seasonal TWS variations

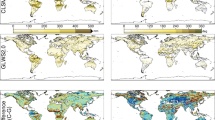

The analysis of hydrological loading displacements highlights the importance of seasonality in terrestrial water variations across the TP. To further investigate this, we examined the seasonal fluctuations in terrestrial water derived from the joint inversion and compared them with independent terrestrial water products from GRACE (i.e., the average of three GRACE mascon products) and GLDAS, as shown in Fig. 6a and c. The water heights from all three datasets exhibit similar spatial patterns of seasonal water fluctuations. However, the joint inversion results offer a more detailed depiction compared to GRACE and GLDAS. For instance, the southern Tibet and Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau regions show stronger annual amplitudes, which can be attributed to the coarse spatial resolution of GRACE data23 and the underestimation of moisture content by GLDAS in regions with highly complex terrain8. In contrast, the northwest TP exhibits smaller annual amplitudes from the joint inversion compared to GRACE, likely due to the sparse distribution of GNSS stations in this region. This leads to a relatively higher weight of GNSS data in the joint inversion, resulting in smaller TWS amplitudes. Additionally, we calculated the average annual precipitation across the TP from 2010 to 2021, shown in Fig. 6d. The spatial distribution of precipitation is highly heterogeneous, with the heaviest rainfall concentrated in the southern Tibet and the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau, similar to the distribution of annual TWS amplitudes. These observations suggest that seasonal precipitation leads to the anomalous annual TWS amplitudes (~ 20 cm) in the TP56. Notably, the joint inversion results do not significantly enhance spatial resolution, reflecting an inherent limitation. However, the reliability of this method is corroborated by two synthetic test results.

The annual TWS amplitudes for (a) joint inversion, (b) GRACE, and (c) GLDAS over the TP, with the pink dots in (a) representing the spatial distribution of GNSS stations. (d) The average annual precipitation in the TP from 2010 to 2021. Note that different colors are used to distinguish between TWS and precipitation. Graphs are created in Generic Mapping Tools (version 6.0.0) software32.

Temporal characteristics of TWS variations

To investigate the temporal evolution of water storage, we calculated TWS variations across the TP using latitude-based weighting. As shown in Fig. 7a, all three TWS time series exhibit clear seasonal patterns that align with the temporal distribution of meteorological precipitation. However, regional average precipitation generally peaks in July, while the terrestrial water reaches its peak with a 1-month delay (Fig. 7b). Additionally, we calculated the Pearson correlation coefficients (PCCs) between the three TWS time series, revealing strong temporal correlations, with PCC values ranging from 0.73 to 0.87.

(a) The time series of latitude-based weighted regional average TWS and precipitation for the TP, where the purple, green, and red solid lines represent results from GRACE, GLDAS, and joint inversion, respectively, and the blue bars represent monthly precipitation data. In the figure, R1, R2, and R3 denote the correlation coefficients between Joint-GRACE, Joint-GLDAS, and GRACE-GLDAS, respectively. (b) The annual cycle of latitude-based weighting regional average TWS and precipitation for the TP. Graphs are created in MATLAB R2020b software (https://ww2.mathworks.cn/products/new_products/release2020b.html).

Due to regional precipitation patterns and the monsoon, water storage variations across the sub-regions of the TP exhibit significant differences. Consequently, we calculated TWS variations for the 12 sub-regions of the TP, as delineated in Fig. 1a, with the results presented in Fig. 8. The findings reveal that the TWS variations derived from the joint inversion generally align with those obtained independently from GRACE and GLDAS data, showing strong correlations across the three methods. However, certain regions exhibit weak correlations (e.g., Inner, Ganges, Qaidam, Hexi, and Yellow regions). For the weak correlations in the Inner, Qaidam, Hexi, and Yellow regions, we hypothesize that minimal fluctuations in water storage in these areas hinder the ability of GRACE and GLDAS data (due to their low signal-to-noise ratio) to accurately capture regional hydrological characteristics. Nevertheless, due to the high sensitivity of GNSS data to local and regional hydrological signals23the TWS variations derived from the joint inversion still exhibit distinct seasonal variations with larger amplitudes. In the case of the Ganges region, the weak correlation may stem from its relatively small size (~ 80,000 km²), which complicates the use of GRACE data to estimate water storage changes. Furthermore, significant data gaps in the GNSS stations in this region (see Figure S1f) impair the interpolation performance of the GMIS software. Consequently, the reduced reliability of the GMIS-interpolated reconstruction negatively affects the TWS variations obtained through the joint inversion.

The latitude-based weighted regional average TWS and precipitation time series for the 12 sub-regions of the TP, with the purple, green, and red solid lines representing the results from GRACE, GLDAS, and joint inversion, respectively. The blue bars represent monthly precipitation data. In the figure, R1, R2, and R3 denote the correlation coefficients between Joint-GRACE, Joint-GLDAS, and GRACE-GLDAS, respectively. Graphs are created in MATLAB R2020b software (https://ww2.mathworks.cn/products/new_products/release2020b.html).

Using joint inversion results to monitor extreme drought events

Recent research has shown that GNSS can capture both short-term changes linked to heavy rainfall events76 and long-term variations driven by climate oscillations11. Due to its highly variable precipitation patterns, the TP is particularly vulnerable to extreme climatic events, such as droughts and floods77. Inspired by the GRACE-based drought severity index (GRACE-DSI)78we calculated the TWS deficit by subtracting the climatological values from the monthly TWS time series derived from joint inversion (shown in the left column of Fig. 9). This deficit was then normalized by dividing by the standard deviations of the climatological values, yielding the Joint-DSI (presented in the right column of Fig. 9). As shown in the left column of Fig. 9, during the 2015–2016 El Niño event (Fig. 11), the central and eastern regions of the TP experienced a particularly severe drought, a phenomenon well documented in previous studies12.

The TWS (left column) and DSI (right column) time series for the 12 sub-regions of the TP, derived from the joint inversion. The solid black lines represent the monthly TWS time series, smoothed using a 3-month moving window to reduce noise, following the method of Thomas et al. (2014)79. The blue dotted lines represent the monthly climatological values, while the red shaded areas highlight the TWS deficit. The dark magenta solid lines depict the Joint-DSI, and the two green horizontal lines correspond to DSI values of -1.5 and 1.5, respectively. The blue bars indicate the monthly deviations of precipitation from the climatological values. Graphs are created in MATLAB R2020b software (https://ww2.mathworks.cn/products/new_products/release2020b.html).

To investigate the causes of this drought event, we calculated the spatial distribution of the summer precipitation anomaly in the TP (Fig. 10), as summer precipitation accounts for 60–70% of the region’s total annual rainfall80. Figure 10 reveals that the central and eastern TP experienced significant precipitation deficits (~ -150 mm) in 2015, directly contributing to the TWS deficit observed in 2016. Meanwhile, a strong El Niño event occurred during 2015/2016, suggesting that the drought was primarily driven by reduced precipitation associated with climate change12. However, it is noteworthy that despite anomalous precipitation in the Ganges and inland regions during 2015, no TWS deficit occurred, and the underlying reasons merit further investigation. Furthermore, as shown in the right column of Fig. 9, there is a lack of synchronization between meteorological indicators (i.e., precipitation anomalies) and the hydrological drought index. Meteorological indicators consistently reach their lowest values before the hydrological drought index, reflecting the typical lag time required for meteorological drought to transition into hydrological drought81.

The spatial distribution of the mean summer precipitation anomaly across the TP over the past 12 years (2010–2021), derived from the average values of the ERA5 and GPM precipitation models. Graphs are created in MATLAB R2020b software (https://ww2.mathworks.cn/products/new_products/release2020b.html).

The correlation between interannual TWS fluctuations and climate indices

In addition to hydrometeorological data, large-scale climate indices, such as ENSO, significantly influence regional water storage variations2,82. The main contributor to water storage changes on the TP, precipitation, is primarily governed by the monsoon, which is itself influenced by ENSO events. Consequently, we further examined the relationship between interannual TWS variations and the ENSO time series37,70.

Figure 11 presents the time series of interannual TWS variations inferred from both the joint inversion and GRACE data across the 12 sub-regions of the TP, with the ENSO time series provided for comparison. The lagged correlation coefficients between these time series are shown in Table 2. As observed in Fig. 11, the interannual TWS variations inferred from the joint inversion and GRACE data show notable differences in most TP basins. This discrepancy may result from the joint inversion method’s incorporation of GNSS constraints, which enhances its sensitivity to variations compared to GRACE data. Nevertheless, strong correlations are observed in certain river basins, such as the Mekong, Salween, and Brahmaputra.

(a-l) The interannual TWS time series for 12 sub-regions of the TP, derived from the joint inversion (purple) and GRACE data (red). (m) The MEI time series along with its interannual variation. It is important to note that all interannual variations have been uniformly filtered using a low-pass filter with a cutoff radius greater than 0.5 cpy. Graphs are created in MATLAB R2020b software (https://ww2.mathworks.cn/products/new_products/release2020b.html).

Furthermore, Table 2 shows that the correlation between the interannual TWS variations derived from the joint inversion and ENSO is stronger than that between the GRACE data and ENSO. This suggests that TWS changes in the TP exhibit interannual oscillations driven by ENSO-related large-scale climate variability2,37. However, it is important to note that interannual fluctuations in the TWS time series lag the climate index by one month. This lag occurs because the teleconnection pattern primarily reflects the overall flow field, rather than localized anomalies83. The combined influence of teleconnection factors is complex, and future studies will focus on elucidating the mechanisms through which these factors affect regional water storage variations. Additionally, we observed both negative and positive correlations with ENSO in different basins, which may be attributed to the influence of regional precipitation patterns and monsoonal dynamics, resulting in significant variations in water storage changes and their responses to large-scale climate across different subregions of the TP.

Discussion

The potential advantages of TWS variations derived from joint inversion

Traditional hydrological methods can only directly measure individual components of TWS, and in-situ gauge-based measurements are particularly challenging in harsh alpine regions. In contrast, hydrogeodesy, an emerging field that leverages space-geodetic tools, especially satellite gravimetry and GNSS techniques, can effectively quantify the distribution and movement of terrestrial water both on, above, and below the Earth’s surface. This approach can accurately measure total TWS changes, thus addressing a critical observational gap in hydrological research11. However, due to topographic constraints and varying levels of economic development across regions, not all areas are equipped with GNSS stations. GNSS data for TWS change inversion is most effective in regions with a dense station network, while areas with sparse GNSS coverage rely on satellite gravimetry missions, such as GRACE, and hydrological models for observation and simulation. However, GRACE suffers from a relatively coarse spatial resolution (~ 300–500 km), and hydrological models cannot fully capture the dynamics of all water components84. Therefore, a joint inversion of GNSS and GRACE data is recommended to leverage the complementary strengths of these two geodetic techniques for enhanced hydrological applications.

Unlike the joint inversion method in the spectral domain, which often require extensive prior parameter settings, our model directly constrains GNSS inversion results in the spatial domain using the 3° equal-area spherical cap of JPL mascon. This approach has been shown to provide more reliable TWS change estimates26,27. If only GNSS-derived deformation is used for TWS change inversion in the TP, the results may be unreliable due to the sparse distribution of GNSS stations in certain areas (e.g., the northwest and inner TP, see Figure S11). However, the joint inversion strategy in this study not only compensates for the sparse GNSS station coverage in the TP but also enhances the signal amplitude in regions with denser GNSS stations, while mitigating the influence of local non-hydrological signals in the GNSS observations20.

Limitations and future directions

The validity of our joint inversion results is supported by the integration of multi-source datasets and exploration of hydroclimatological applications. Nevertheless, GNSS displacements are affected by systematic errors, including thermal expansion effects, draconitic signals, and common mode errors. Notably, The Earth model utilized in our inversion, based on the PREM, may present limitations due to the distinct lithospheric structure of the TP. Wang et al. (2013)65 highlighted that the TP exhibits notable differences in crustal thickness and elastic properties compared to the globally averaged values of PREM. For instance, Wang et al. (2013)65 introduced MQ-PREM, incorporating Crust 2.0 data specific to the TP. Their study demonstrated that while PREM suffices for GRACE-based inversions, given GRACE’s primary reliance on direct gravitational attraction, it may not accurately capture the elastic response in GNSS-derived vertical displacements. Synthetic tests indicated that employing PREM for GPS data inversion in the TP could result in errors ranging from approximately 2 to 15 mm/yr in estimates of equivalent water thickness (EWT) trends at higher spatial resolutions (degrees 60–180), contingent upon the realism of the crustal model used65. In our investigation, we utilized the PREM-based load Love numbers introduced by Wang et al. (2012)63 to align with established geodetic conventions. Nevertheless, the relatively low resolution of GRACE data (~ 300–500 km) may have attenuated these influences within our combined inversion analysis, given that the spatial constraints imposed by GRACE mascons (e.g., JPL 3° equal-area caps) likely diminished the sensitivity to local crustal irregularities. In addition, the sparse distribution of GNSS stations in the northwestern and inner TP regions (see Fig. 1a) could magnify uncertainties in areas where discrepancies in Earth models are prominent. To enhance the isolation of ‘clean’ hydrological load deformation, future research endeavors should focus on the development and exploration of sophisticated data processing methodologies and more comprehensive geophysical models, such as region-specific Earth structures (e.g., MQ-PREM).

The combined utilization of GNSS and GRACE data presents significant potential for future applications, particularly in challenging mountainous areas such as the TP, the focal point of this investigation. Subsequent studies should prioritize the enhancement of the joint inversion methodology to overcome these constraints. One approach involves integrating sophisticated models to accommodate thermal expansion and other non-hydrological signals in GNSS time series, thereby augmenting the precision of TWS change assessments. Furthermore, the incorporation of additional geodetic data sources like InSAR (Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar) could offer deeper insights into local hydrological phenomena. Advancements in robust interpolation techniques and the formulation of region-specific Earth models are imperative for enhancing the dependability of high-resolution TWS monitoring in seismically intricate areas.

Summary and conclusion

In this study, we propose the joint inversion of GNSS and GRACE data to estimate TWS variations across the TP in the spatial domain. The aim is to enhance the reliability and accuracy of the joint inversion results while exploring potential applications. By integrating the TWS variations derived from the joint inversion with hydrometeorological data, we investigate the complex dynamics of TWS variations and the associated climate response processes in the TP. The key findings are as follows:

(1) The results of two synthetic tests demonstrate that, despite the coarse spatial resolution of GRACE observations (around 300–500 km) and the sparse distribution of GNSS stations across the TP, the joint inversion of GNSS and GRACE data significantly enhances the reliability and accuracy of TWS variations, particularly in the northwest and inland regions of the TP.

(2) Due to differences in observation and modeling methods, both GRACE and GLDAS tend to underestimate hydrologically induced load deformation, whereas GNSS is more sensitive to local and regional hydrological signals, resulting in significantly larger surface vertical deformations.

(3) A comparison of TWS variations estimated by the joint inversion with independent TWS products (i.e., GLDAS and GRACE) reveals that all three datasets exhibit similar spatial patterns in annual amplitudes, primarily driven by seasonal precipitation. However, the joint inversion offers more detailed spatial information than either GRACE or GLDAS. These datasets also demonstrate strong temporal consistency and high correlation. The precipitation peak occurs in July, about one month earlier than the TWS peak, indicating that rainfall infiltration in the TP typically lasts around one month.

(4) The TWS changes estimated by the joint inversion effectively capture the 2015/2016 drought event in the central and eastern TP. Analysis of spatial precipitation distribution reveals that precipitation anomalies were the primary drivers of this drought, although hydrological drought showed a delayed response to meteorological drought.

(5) Interannual changes in TWS across the TP sub-basins show a moderate correlation with the ENSO index, with a one-month lag. This indicates that ENSO-related climate fluctuations drive the interannual oscillations in water storage within the TP.

Data availability

The GNSS data we used are part of the Crustal Movement Observation Network of China (CMONOC), Nevada Geodetic Laboratory (NGL), and Myanmar-India-Bangladesh-Bhutan (MIBB) networks, we can download them separately from the websites ftp://ftp.cgps.ac.cn/products/position; http://geodesy.unr.edu/; ftp://datacollection.earthobservatory.sg/. GRACE mascon data are respectively from the Center for Space Research (CSR) at the University of Texas, the Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC) and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), we can download them separately from the websites http://www2.csr.utexas.edu/grace/; https://grace.jpl.nasa.gov/data/get-data/; https://earth.gsfc.nasa.gov/. The monthly EWH products from the GLDAS were downloaded from the website https://disc.gsfc.nasa.gov/; the monthly precipitation data, monthly temperature data and the hourly temperature data from the ERA5 dataset were downloaded from the website https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/; the monthly precipitation data of GPM were downloaded from the websites https://disc.gsfc.nasa.gov/; and the monthly temperature data of GHCN_CAMS were downloaded from the website https://psl.noaa.gov/. The ENSO index version 2 (MEI.v2) were used to study the interannual response of global climate, and the data were downloaded from the website https://psl.noaa.gov/enso/mei/. we can provide all the processed datasets upon request made to the corresponding author of the paper.

References

Tapley, B. D. et al. Contributions of GRACE to Understanding climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 9 (5), 358–369. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-019-0456-2 (2019).

Xie, J. K. et al. Understanding the impact of Climatic variability on terrestrial water storage in the Qinghai-Tibet plateau of China. Hydrolog Sci. J. 67 (6), 963–978. https://doi.org/10.1080/02626667.2022.2044482 (2022).

Long, D. et al. Global analysis of Spatiotemporal variability in merged total water storage changes using multiple GRACE products and global hydrological models. Remote Sens. Environ. 192, 198–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2017.02.011 (2017).

Yao, T. D. et al. Different glacier status with atmospheric circulations in Tibetan Plateau and surroundings. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2, 663–667. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1580 (2012).

Yao, T. D. et al. The imbalance of the Asian water tower. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 618–632. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-022-00299-4 (2022).

Li, X. Y. et al. Climate change threatens terrestrial water storage over the Tibetan Plateau. Nat. Clim. Chang. 12, 801–807. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-022-01443-0 (2022).

You, Q. L. et al. Elevation dependent warming over the Tibetan Plateau: patterns, mechanisms and perspectives. Earth Sci. Rev. 210, 103349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2020.103349 (2022).

Scanlon, B. R. et al. Global models underestimate large decadal declining and rising water storage trends relative to GRACE satellite data. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 115, E1080–E1089. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1704665115 (2018).

Yi, S. & Sun, W. K. Evaluation of glacier changes in high-mountain Asia based on 10year GRACE RL05 models. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth. 119 (3), 2504–2517. https://doi.org/10.1002/2013JB010860 (2014).

Chen, J. L. et al. Applications and challenges of GRACE and GRACE Follow–On satellite gravimetry. Surv. Geophys. 43, 305–345. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10712-021-09685-x (2022).

White, A. M. et al. A review of GNSS/GPS in hydrogeodesy: hydrologic loading applications and their implications for water resource research. Water Resour. Res. 58, e2022WR032078. https://doi.org/10.1029/2022WR032078 (2022).

Pan, Y. J. et al. Spatiotemporal variability at seasonal and interannual scales of terrestrial water variation over Tibetan Plateau from geodetic observations. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/10095020.2024.2331553 (2024).

Song, C. Q. et al. Can mountain glacier melting explains the GRACE-observed mass loss in the Southeast Tibetan Plateau: from a climate perspective? Glob Planet. Chang. 124, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2014.11.001 (2015).

Zhang, G. Q. et al. Increased mass over the Tibetan Plateau: Fom lakes or glaciers? Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 2125–2130. https://doi.org/10.1002/grl.50462 (2013).

Wang, Q. Y., Yi, S. & Sun, W. K. The changing pattern of lake and its contribution to increased mass in the Tibetan Plateau derived from GRACE and ICESat data. Geophys. J. Int. 207, 528–541. https://doi.org/10.1093/gji/ggw293 (2016).

Xiang, L. W. et al. Groundwater storage changes in the Tibetan Plateau and adjacent areas revealed from GRACE satellite gravity data. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 449, 228–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2016.06.002 (2016).

Zou, Y. G. et al. Solid water melt dominates the increase of total groundwater storage in the Tibetan Plateau. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL100092. https://doi.org/10.1029/2022GL100092 (2022).

Yang, X. C. et al. Reconstruction of continuous GRACE/GRACE-FO terrestrial water storage anomalies based on time series decomposition. J. Hydrol. 603, 127018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2021.127018 (2021).

Gou, J. Y. & Soja, B. Global high-resolution total water storage anomalies from self-supervised data assimilation using deep learning algorithms. Nat. Water. 2, 139–150. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44221-024-00194-w (2024).

Jiang, Z. S. et al. Characterizing multifarious hydroclimatic patterns using geodetic measurements in the Australian Mainland. J. Hydrol. 642, 131792. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2024.131792 (2024).

Argus, D. F., Fu, Y. N. & Landerer, F. W. Seasonal variation in total water storage in California inferred from GPS observations of vertical land motion. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41 (6), 1971–1980. https://doi.org/10.1002/2014GL059570 (2014).

Enzminger, T. L., Small, E. E. & Borsa, A. A. Accuracy of snow water equivalent estimated from GPS vertical displacements: A synthetic loading case study for Western U.S. Mountains. Water Resour. Res. 54, 581–599. https://doi.org/10.1002/2017WR021521 (2018).

Knappe, E. et al. Downscaling vertical GPS observations to derive watershed-scale hydrologic loading in the Northern Rockies. Water Resour. Res. 55, 391–401. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018WR023289 (2019).

Fok, H. S. & Liu, Y. X. An improved GPS-inferred seasonal terrestrial water storage using terrain-corrected vertical crustal displacements constrained by GRACE. Remote Sens. 11 (12), 1433. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs11121433 (2019).

Adusumilli, S. et al. A decade of water storage changes across the contiguous united States from GPS and satellite gravity. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46 (22), 13006–13015. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019GL085370 (2019).

Carlson, G., Werth, S. & Shirzaei, M. Joint inversion of GNSS and GRACE for terrestrial water storage change in California. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 127, e2021JB023135 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1029/2021JB023135

Argus, D. F. et al. Subsurface water Fluxin California’s central valley and its source watershed from space geodesy. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL099583. https://doi.org/10.1029/2022GL099583 (2022).

Zhu, H. et al. Characterizing hydrological droughts within three watersheds in Yunnan, China from GNSS-inferred terrestrial water storage changes constrained by GRACE data. Geophys. J. Int. 235 (2), 1581–1599. https://doi.org/10.1093/gji/ggad321 (2023).

Li, X. P. et al. Investigation of 2020–2022 extreme floods and droughts in Sichuan Province of China based on joint inversion of GNSS and GRACE/GFO data. J. Hydrol. 632, 130868. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2024.130868 (2024).

Chen, T. et al. Investigating terrestrial water storage variation and its response to climate in southeastern Tibetan Pateau inferred through space geodetic observations. J. Hydrol. 640, 131742. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2024.131742 (2024).

Tang, M. et al. Insights into water mass change in the Yangtze river basin from the spectral integration of GNSS and GRACE observations. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 644, 118929. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2024.118929 (2024).

Wessel, P. et al. The generic mapping tools version 6. Geochem. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 20, 5556–5564. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019GC008515 (2019).

Zhang, G. Q. et al. Lakes’ state and abundance across the Tibetan Plateau. Chin. Sci. Bull. 59 (24), 3010–3021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11434-014-0258-x (2014).

Duan, A. M. & Xiao, Z. X. Does the climate warming hiatus exist over the Tibetan Plateau?? Sci. Rep. 5 (1), 13711. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep13711 (2015).

Blewitt, G., Hammond, W. C. & Kreemer, C. Harnessing the GPS data explosion for interdisciplinary science. Eos 99, 485. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018EO104623 (2018).

Mallick, R. et al. Active convergence of the India-Burma-Sunda plates revealed by a new continuous GPS network. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth. 124 (3), 3155–3171. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018jb016480 (2019).

He, M. L. et al. The interannual fluctuations in mass changes and hydrological elasticity on the Tibetan Plateau from geodetic measurements. Remote Sens. 13 (21), 4277. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs13214277 (2021).

Bertiger, W. et al. GipsyX/RTGx, A new tool set for space geodetic operations and research. Adv. Space Res. 66 (3), 469–489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asr.2020.04.015 (2020).

Altamimi, Z. et al. ITRF2014: A new release of the international terrestrial reference frame modeling nonlinear station motions. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth. 121 (8), 6109–6131. https://doi.org/10.1002/2016jb013098 (2016).

Lyard, F. et al. Modelling the global ocean tides: modern insights from FES2004. Ocean. Dyn. 56, 394–415. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10236-006-0086-x (2006).

Petit, G. & Luzum, B. IERS Technical Note & IERS Conventions. No. 36. (International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service, 2010).

Wahr, J. et al. The use of GPS horizontals for loading studies, with applications to Northern California and Southeast Greenland. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth. 118, 1795–1806. https://doi.org/10.1002/jgrb.50104 (2013).

Yang, X. H. et al. Investigating terrestrial water storage changes in Southwest China by integrating GNSS and GRACE/GRACE-FO observations. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 48, 101457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrh.2023.101457 (2023).

Wu, D. C., Yan, H. M. & Yuan, S. L. L1 regularization for detecting offsets and trend change points in GNSS time series. GPS Solut. 22 (3), 88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10291-018-0756-4 (2018).

Dill, R. & Dobslaw, H. Numerical simulations of global-scale high-resolution hydrological crustal deformations. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth. 118, 5008–5017. https://doi.org/10.1002/jgrb.50353 (2013).

Yan, H. M. et al. Contributions of thermal expansion of monuments and nearby bedrock to observed GPS height changes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L13301. https://doi.org/10.1029/2009gl038152 (2009).

Liu, N. et al. A MATLAB-based Kriged Kalman filter software for interpolating missing data in GNSS coordinate time series. GPS Solut. 22, 25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10291-017-0689-3 (2017).

Fu, Y. N., Argus, D. F. & Landerer, F. W. GPS as an independent measurement to estimate terrestrial water storage variations in Washington and Oregon. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth. 120 (1), 552–566. https://doi.org/10.1002/2014JB01141 (2015).

Watkins, M. M. et al. Improved methods for observing earth’s time variable mass distribution with GRACE using spherical cap mascons. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth. 120, 2648–2671. https://doi.org/10.1002/2014JB011547 (2015).

Save, H., Bettadpur, S. & Tapley, B. D. High-resolution CSR GRACE RL05 mascons. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth. 121 (10), 7547–7569. https://doi.org/10.1002/2016JB013007 (2016).

Loomis, B. D., Luthcke, S. B. & Sabaka, T. J. Regularization and error characterization of GRACE mascons. J. Geod. 93, 1381–1398. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00190-019-01252-Y (2019).

Yi, S. & Sneeuw, N. Filling the data gaps within GRACE missions using singular spectrum analysis. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth. 126 (5), e2020JB021227. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020JB021227 (2021).

Zhang, G. Q. et al. Comprehensive Estimation of lake volume changes on the Tibetan Plateau during 1976–2019 and basin-wide glacier contribution. Sci. Total Environ. 772, 145463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.145463 (2021).

Tao, H. et al. A landsat-derived annual inland water clarity dataset of China between 1984 and. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 14(1), 79–94 (2018). https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-14-79-2022 (2022).

Sha, Y. Y. et al. Distinct impacts of the Mongolian and Tibetan Plateaus on the evolution of the East Asian monsoon. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 120 (10), 4764–4782. https://doi.org/10.1002/2014JD022880 (2015).

Zhang, H. et al. Monitoring the Spatiotemporal terrestrial water storage changes in the Yarlung Zangbo river basin by applying the P-LSA and EOF methods to GRACE data. Sci. Total Environ. 713, 136274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.136274 (2020).

Jiao, J. S. et al. Basin mass changes in Finland from GRACE: validation and explanation. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth. 127 (6), e2021JB023489. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021JB023489 (2022).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. Roy Meteor. Soc. 146 (730), 1999–2049. https://doi.org/10.1002/QJ.3803 (2020).

Skofronick-Jackson, G. et al. The global precipitation measurement (GPM) mission for science and society. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 98 (8), 1679–1695. https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-15-00306.1 (2017).

Wolter, K. & Timlin, M. S. El niño/southern Oscillation behaviour since 1871 as diagnosed in an extended multivariate ENSO index (MEI.ext). Int. J. Climatol. 31 (7), 1074–1087. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.2336 (2011).

Farrell, W. E. Deformation of the Earth by surface loads. Rev. Geophys. 10 (3), 761–797. https://doi.org/10.1029/RG010i003p00761 (1972).

Chen, C. et al. Comparative analysis of green’s functions and Slepian basis functions for GNSS inversion of terrestrial water. Acta Geodaetica Cartogr. Sin. 52 (12), 2066–2077. https://doi.org/10.11947/j (2023). AGCS.2023.20220624.

Wang, H. S. et al. Load love numbers and green’s functions for elastic Earth models PREM, iasp91, ak135, and modified models with refined crustal structure from crust 2.0. Comput. Geosci. 49, 190–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cageo.2012.06.022 (2012).

Dziewonski, A. M. & Anderson, D. L. Preliminary reference Earth model. Phys. Earth Planet. In. 25, 297–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/0031-9201(81)90046-7 (1981).

Wang, H. S. et al. Effects of the Tibetan Plateau crustal structure on the inversion of water trend rates using simulated GRACE/GPS data. Terr. Atmos. Ocean. Sci. 24 (4), 505–512. https://doi.org/10.3319/TAO.2012.09.21.01 (2013).

Chanard, K. et al. Modeling deformation induced by seasonal variations of continental water in the Himalaya region: Sensitivity to Earth elastic structure. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 119(6), 5097–5113 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1002/2013jb010451 (2014).

Chen, T. et al. Spatiotemporal variability of terrestrial water storage and climate response processes in the Tianshan from geodetic observations. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 56, 102061. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrh.2024.102061 (2024).

Chen, T. et al. Integrating GNSS and GRACE observations to investigate water storage variations across different Climatic regions of China. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 63, 5801715. https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2025.3563095 (2025).

Bevis, M. et al. Seasonal fluctuations in the mass of the Amazon river system and earth’s elastic response. Geophys. Res. Lett. 32 (16), L16308. https://doi.org/10.1029/2005GL023491 (2005).

Hsu, Y. J. et al. Assessing seasonal and interannual water storage variations in Taiwan using geodetic and hydrological data. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 550, 116532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2020.116532 (2020).

Zheng, S. et al. High Spatial resolution in total water storage variations inferred from GPS: case study in the great lakes watershed, US. Water Resour. Res. 60, e2023WR035213. https://doi.org/10.1029/2023WR035213 (2024).

Funning, G. J. et al. A method for the joint inversion of geodetic and seismic waveform data using ABIC: application to the 1997 manyi, tibet, earthquake. Geophys. J. Int. 196, 1564–1579. https://doi.org/10.1093/gji/ggt406 (2014).

Pan, Y. J. et al. Contemporary mountain-building of the Tianshan and its relevance to geodynamics constrained by integrating GPS and GRACE measurements. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth. 124 (11), 171 – 188. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JB017566 (2019).

Borsa, A., Agnew, D. C. & Cayan, D. R. Ongoing drought-induced uplift in the Western United States. Science 345 (6204), 1587–1590. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13275 (2014).

Pan, Y. J. et al. Intradecadal fluctuations and three-dimensional crustal kinematic deformation of the Tianshan and Pamir derived from multi-geodetic imaging. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth. 128 (1), e2022JB025325. https://doi.org/10.1029/2022JB025325 (2023).

Heki, K. & Arief, S. Crustal response to heavy rains in Southwest Japan 2017–2020. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 578, 117325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2021.117325 (2022).

Zhao, Y. & Zhou, T. J. Interannual variability of precipitation recycle ratio over the Tibetan Plateau. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 126 (2), e2020JD033733. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020jd033733 (2021).

Zhao, M. et al. A global gridded dataset of GRACE drought severity index for 2002-14: comparison with PDSI and SPEI and a case study of the Australia millennium drought. J. Hydrometeorol. 18, 2117–2129. https://doi.org/10.1175/jhm-d-16-0182.1 (2017).

Thomas, A. C. et al. A GRACE-based water storage deficit approach for hydrological drought characterization. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41 (5), 1537–1545. https://doi.org/10.1002/2014GL059323 (2014).

Wang, X. J., Pang, G. Q. & Yang, M. X. Precipitation over the Tibetan Plateau during recent decades: A review based on observations and simulations. Int. J. Climatol. 38 (3), 1116–1131. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.5246 (2018).

Van Loon, A. F. Hydrological drought explained. WIREs Water. 2, 359–392. https://doi.org/10.1002/wat2.1085 (2015).

Dai, A. Drought under global warming: A review. WIREs Clim. Change. 2 (1), 45–65. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.81 (2011).

Liu, Z. F. et al. Acceleration of Western Arctic sea ice loss linked to the Pacific North American pattern. Nat. Commun. 12 (1), 1519. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-21830-z (2021).

Soltani, S. S., Ataie-Ashtiani, B. & Simmons, C. T. Review of assimilating GRACE terrestrial water storage data into hydrological models: advances, challenges and opportunities. Earth Sci. Rev. 213, 103487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2020.103487 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Editor Prof. Mohammad Tourian and two anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful reviews and constructive comments that helped improve the quality of this manuscript. This work is funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42304031, 42274033 and 42304020), Basic Science Center Project of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42388102).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.H. and T.C. wrote the main manuscript text, T.C., Y.P., J.J. and W.J. revised the manuscript, T.C. and Y.P. designed data processing code, and Y.L. and Q.W. checked English grammer. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

He, M., Chen, T., Pan, Y. et al. Spatiotemporal variability of terrestrial water storage over the Tibetan Plateau from the joint inversion of GNSS and GRACE observations. Sci Rep 15, 27168 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12635-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12635-x