Abstract

Conventional Computed Tomography (CCT) measures the total x-ray attenuation for a whole x-ray spectrum, which can be used for medical diagnosis of anatomically visible pathologies. Spectral Computed Tomography (SCT) is an extension of CCT and enables the separation of two distinct processes of x-ray attenuation in tissues. The combined pair of attenuation contributions is material-specific, enabling rapid quantification of in vivo tissue composition. The combined, detailed knowledge about anatomy and pathological tissue composition allows for disease phenotyping, with great potential for improved medical diagnosis. In this paper we introduce X-Ray Attenuation Decomposition (XAD), to intuitively display and quantify the material contents of biological tissues and integrate it into the conventional, anatomical visualization of CT images. XAD gives an interactive display of material contents superimposed on anatomical information, making it easy to identify both the anatomical location as well as the concentrations of specific materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Computed tomography is an x-ray based medical imaging technique that generates high spatial-resolution cross-sectional images of the body which are used for medical diagnosis, to monitor treatment by following patients over time, and to guide interventions1.

Conventional Computed Tomography (CCT) images display the Hounsfield Unit (HU) value for each voxel, which represents the local x-ray attenuation \(\mu\) relative to the attenuation of water (\(\mu _{\text {water}}\)):

Because \(\mu\) is a material dependent property, the HU value can be used to identify different tissue types. However, the distinction between biological tissues based on HU is limited, since \(\mu\) depends on both material composition and x-ray energy. As CT uses a broad spectrum of x-ray energies and voxels can contain mixtures of materials, different combinations of materials in a voxel can result in the same HU value, making it impossible to calculate the exact material composition. There are many examples in medical imaging, where exact material content is important for diagnosis, e.g. the concentration of iodine in blood or tissue to determine organ perfusion, quantification of the degree of stenosis in a blood vessel, elucidating the nature of a cystic lesion2, establishing the presence of uric acid in kidney stones to choose the right medical treatment3, or determining the concentration of fat in a lesion to rule out malignancy4.

The introduction of dual-energy CT, also known as spectral CT (SCT), solved most of these problems2,3,4. With SCT, two acquisitions of the same object are made with different x-ray spectra corresponding to two distinct effective x-ray energies. Assuming material content is the same for both acquisitions, the known energy dependence of x-ray attenuation can be exploited to determine material content. As the measured differences in attenuation are small in biological tissues, it is key that both macroscopic bulk patient motion as well as motion due to physiological and metabolic processes between the acquisitions is minimal. Thus, ideally the two acquisitions should be made at the same time.

The first clinical CT scanner capable of making a SCT acquisition in one rotation was introduced in 20065. Since then, several different types of SCT systems have become available clinically: dual source scanners by Siemens Healthineers (Erlangen, Germany), rapid tube potential switching systems by GE Healthcare (Waukesha, Wisconsin) and dual layer detector scanners by Philips Healthcare (Best, the Netherlands). Nevertheless, the number of clinical applications of SCT is still limited and is primarily focused on improving image contrast by using either virtual mono-energetic imaging, virtually removing materials (e.g. iodine and calcium) and on iodine quantification. Despite the potentially high clinical impact, relatively little effort has been spent on quantification of tissue composition other than iodine density maps, detection of uric acid, and more recently the removal of calcium to visualize bone oedema6.

A generic tool to visualize the in-vivo atomic contents in SCT images is sorely lacking. Here we introduce an intuitive method to display the material contents of biological tissues and integrate it into the conventional, anatomical visualization of CT images. The result is an interactive display of material contents superimposed on anatomical information, making it easy to identify both the anatomical location as well as the concentrations of specific materials. The uniqueness of this method is that the interaction is bi-directional, allowing for selection of a specific material and to map this material across different anatomical locations. Conversely, an anatomical region can be selected, and the method can be used to display its atomic content. Our method paves the way for many new applications for in vivo material identification and quantification, which could be used to bolster medical diagnosis.

Materials and methods

All methods and data usage was performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the MREC NedMec medical research ethics committee waved the need for ethical approval. The requirement for written informed consent was waived by the MREC NedMec medical research ethics committee, because only anonymous data was used retrospectively.

Patients

The clinical CT scans shown in this manuscript were provided to the authors to illustrate the developed methods only. Those scans were extracted by the datamanager of the division of Imaging and Oncology of the UMC Utrecht from an anonymized database of existing patient scans, such that only age, sex and the clinical indication was available to the authors.

A digital phantom consisting of cylinders filled with six distinct materials labeled \(\hbox {m}_0\) to \(\hbox {m}_5\); axial slices through the phantom show these materials as partially overlapping circles in (a) and (b). In (a) some 3D Gaussian noise is added, resulting in the blurring of the points for the different materials in XAD graph (c). In (b) some 3D blurring is added in addition to the noise to simulate mixtures of materials near the edges of cylinders; these mixtures show up as lines in the XAD graph (d). As the XAD graph is a 2D histogram, the brightness is used to indicate the number of voxels in a bin.

Graphical representation of decomposition in three base materials. The blue, yellow, and magenta points represent the locations of samples that would be filled 100% with one base material. The solid lines of changing colors between those locations indicate the mixtures between two base materials. The triangle enclosed by the three solid lines delimits the range of samples that can be decomposed into these three base materials. The unknown sample (cyan) is decomposed into these three base materials, by virtually replacing its volume fraction of each base material with another base material. The dashed magenta line is parallel to the \(\hbox {base}_2\) (magenta) to \(\hbox {base}_3\) (yellow) line, showing the effect of virtually replacing the fraction of \(\hbox {base}_2\) material in the sample with \(\hbox {base}_3\) material. The point where the dashed magenta line crosses the blue-yellow line indicates where \(\hbox {base}_2\) material is depleted from the sample. Comparing the length of the dashed magenta line to the length of the magenta-yellow line gives the volume fraction of \(\hbox {base}_2\) material that is present in the sample. Analogously the volume fractions of the other two base materials can be calculated using the blue and yellow dashed lines, which are parallel to the \(\hbox {base}_1\) (blue) to \(\hbox {base}_2\) (magenta) line and the \(\hbox {base}_3\) (yellow) to \(\hbox {base}_1\) (blue) line, respectively.

(a–d) Abdominal CT angiography scan of a 40-year-old female patient suspected of liver adenoma. Selection of a region of interest (yellow ellipse) in the XAD graph (a) results in segmentation of all anatomical compartments containing fat (yellow overlay) in the corresponding contrast-enhanced abdomen scan (c). Selecting a line segment (magenta box) in the XAD graph (b) results in selection of all voxels containing blood mixed with high concentrations of iodine (magenta overlay in d), as can be found in the vasculature, the renal cortex, the spleen as well as a hypervascular liver tumor. (e–f) A contrast enhanced chest CT scan, where common human tissue materials are anatomically indicated in (e) and their corresponding locations in the XAD graph show up in (f): lung tissue, predominantly containing air (green), fat (yellow), muscle/soft tissue (dark blue), blood/myocardium with little iodine (red), iodinated blood (magenta), vertebral bone (cyan), cartilage (orange).

Cardiac CT angiography scan of a 71-year-old male patient after open aortic arch repair shows two regions of interest (cyan ROIs in a) with HU value similar to that of contrast-enhanced blood in the aortic arch (magenta ROI in a), suspected for graft leakage. The ROI average and (standard deviation) in the conventional image are 359 (20) HU for the magenta ROI and 349 (21) HU and 313 (40) HU for the cyan ROIs. XAD analyses clearly identifies the magenta ROI as a mixture of iodine and blood and shows that the cyan ROIs do not contain blood with iodine, but are in fact some other material (b) because they reside in a completely different part of the XAD plot. This material turned out to be surgical felt to support sutures.

CT angiography of carotid arteries of a 77-year-old woman, showing an occlusion in the right carotid artery. In the axial (a) and coronal (b) view, the occlusion is segmented (cyan) and compared to the same location in the left carotid artery (magenta). The corresponding XAD plots show a clear difference in material composition of the right carotid artery (cyan dots in panel c), and left carotid artery (magenta dots in panel d): the voxels of the healthy left carotid artery are all on the iodinated blood line, while the voxels of the occluded right carotid artery show a little iodinated blood, and some calcifications and also a large pool (yellow ellipse) of soft tissue material without iodinated blood or calcium, likely representing thrombus.

Results

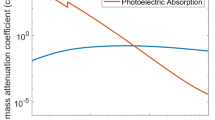

Key to our method, is that the two acquired images of SCT are used to distinguish the two fundamental processes that cause x-ray attenuation: Compton scattering (CS) and photoelectric absorption (PE), with corresponding attenuation coefficients \(\mu _{CS}\) and \(\mu _{PE}\). Because these two processes have different dependencies on both x-ray energy and material, the numerical values of the pair of attenuation coefficients \((\mu _{PE},\mu _{CS})\) are characteristic of the attenuating material. To calculate these pairs of attenuation coefficients, we use two virtual mono-energetic reconstructions which can be generated on all SCT scanners.

Analogous to CCT, for SCT two separate Hounsfield units can be defined for attenuation by Compton scatter and photoelectric absorption, respectively:

where \(\mu _{PE,\text {water}}\) and \(\mu _{CS,\text {water}}\) are the PE and CS component of \(\mu _{\text {water}}\) , such that \(\mu _{PE,\text {water}}+\mu _{CS,\text {water}}=\mu _{\text {water}}\) and \(HU_{PE}+HU_{CS}=HU\).

An illustrative way to depict the \(HU_{PE}\) and \(HU_{CS}\) of a CT scan is to construct a so-called X-Ray Attenuation Decomposition (XAD) graph, by creating a 2D histogram, binning all voxels with the same values of \(HU_{PE}\) and \(HU_{CS}\). Such XAD graphs can be used to quickly visualize the material composition of each voxel of a CT scan.

Figure 1 explains the basics of an XAD graph, using a digital phantom, consisting of six cylinders filled with distinct materials. The used materials are those that can be expected to show up in CT scans of humans: 50% water and 50% cortical bone (\(\hbox {m}_0\)), blood with 0.5% iopromide (\(\hbox {m}_1\)), blood (\(\hbox {m}_2\)), soft tissue (\(\hbox {m}_3\)), adipose tissue (\(\hbox {m}_4\)), and air (\(\hbox {m}_5\)). For the human tissues we used the chemical definitions of the International Commisssion on Radiological Protection (ICRP) as provided by Berger et al.7 Pure materials (i.e. composed of a single tissue) show up as distinct points in an XAD graph. Adding noise to the phantom results in blurring of these points. Blurring the images of the digital phantom before adding noise results in virtual mixtures of materials across the boundaries of the cylinders, which show up as lines in the XAD graphs, where the relative distance along the line between two pure materials represents the volume fractions of the two materials involved.

By identifying different base materials in an XAD graph, any mixture of these materials can be quickly split up in its base material fractions. For different anatomical regions, different sets of base materials should be used. Because SCT uses two measurements, this method can be used to calculate the fractions of only two or three distinct base materials. In the latter case, we need to impose the additional constraint that the sum of the volume fractions of the three base materials equals 1. The three base materials decomposition is shown graphically in Fig. 2. This decomposition scheme calculates the volume fractions of each material by virtually replacing each base material with another one, which is also used to construct images with a virtually removed base material (e.g. iodine and calcium).

XAD and clinical examples

XAD graphs can be used in tandem with the anatomical information of the CT scan, thereby enabling interactive, qualitative and quantitative material analysis in specific organs or anatomical structures. Several uses of XAD graphs will be exemplified below. The examples are not finished products, but are intended to demonstrate how actual XAD information can be translated into clinical applications.

XAD-based segmentation and anatomical quantification

A volumetric CT scan can be segmented based on material content and then analyzed anatomically. Figure 3a shows an iodinated contrast-material enhanced CT scan of the abdomen and the resulting XAD graph. In the XAD graph, several distinct clusters of voxels and connecting lines can be distinguished. By selecting a subset of voxels in the XAD graph (Fig. 3a) i.e. by choosing a certain range in (\(\mu _{PE},\mu _{CS}\)), specific biological tissues can be identified in the corresponding CT scan (Fig. 3b). Voxels of the original CT scan corresponding to that range in (\(\mu _{PE},\mu _{CS}\)) are shown as an overlay on top of the conventional CT scan reconstruction, enabling anatomical correlation.

The International Commission on Radiation Units and Measurements (ICRU) has published the atomic composition of several human tissues in report 448. Using the x-ray attenuation data for compounds as published in the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Standard Reference Databases 126 and 89,10, the location of the ICRU-44 tissues and other materials can be identified in the XAD graph. For example, in Fig. 3a, a region of interest (ROI) containing adipose tissue can be selected in the XAD graph based on a pre-specified precise combination of (\(\mu _{PE},\mu _{CS}\)), which then highlights the corresponding anatomical locations containing fat (Fig. 3b). Using this methodology, the amount of fat in specific anatomical compartments, organs or lesions can be quantified. This approach greatly simplifies current labor-intensive methods that rely on manual segmentation. Similarly, by selecting a certain line segment in the XAD graph (Fig. 3c) all blood with a pre-specified range of iodine content can be selected in the corresponding CT scan (Fig. 3d), making it possible to detect e.g. areas of diminished or enhanced blood flow or to precisely quantify enhancement of tumors. This method for quantification can be used for any material or mixture of materials, if the Compton scatter and photoelectric absorption of the different constituents are known for the used diagnostic x-ray energy range. Even if the exact atomic composition of a certain material is not known, this method is applicable if one can make a SCT of a phantom or sample with a known concentration of that material and identifies the corresponding location in the XAD graph.

Figures 3e,f shows the photoelectric and Compton scatter components of several common human tissues indicated on a CT scan (Fig. 3e) and their corresponding unique locations in the XAD graph (Fig. 3f). The locations of these materials are in good agreement with the corresponding ICRU-44 tissues definitions.

Anatomical segmentation and qualitative XAD-based material separation

Conversely, the XAD graph can also be used qualitatively. Figure 4 demonstrates a possible clinical utility of this approach in a patient who underwent aortic arch stent placement and complained of postoperative chest pain. Figure 4 shows two para-aortic areas with similar HU value as the blood pool in the aorta, representing possible aortic perforation and contrast leakage. In fact, these spots represented surgical material. Visualization of these ROIs by their coefficients (\(\mu _{PE},\mu _{CS}\)) in the XAD graph shows that these are in an area of the XAD graph, which is substantially removed from the line of voxels corresponding to iodinated blood, so that leakage can be confidently ruled out.

Anatomical segmentation and XAD-based quantification

An XAD graph can not only aid in identifying specific materials, but it can also help to quantify them. This can be useful in a variety of disease processes and is several orders of magnitude faster compared to image-based manual segmentations by experts.

An example of a disease process that can benefit from improved quantitative analysis is atherosclerosis. Atherosclerotic plaques are complex tissue deposits consisting of lipids, inflammatory cells, necrotic tissue, microvasculature and calcium11. Quantitative analysis of atherosclerotic plaques is an active field of research that has been linked to improved prediction of cardiovascular events12. Figure 5 shows an example of a carotid artery harboring an atherosclerotic plaque. The tissue content of the segmented atherosclerotic plaque in the carotid vessel wall can be assessed directly in the XAD graph, enabling identification and quantification of different atherosclerotic plaque components. For example, by counting the number of voxels marked in the XAD overlay inside a selected region, the total volume of specific tissue components such as calcium or lipids in the plaque can be assessed. Furthermore, the plaques in the arteries show up in the XAD graphs as the triangle of a mixture of iodinated blood, lipids and calcium-hydroxyapatite, so a three-base-materials decomposition the three-materials decomposition can be applied. This way it is possible to calculate the calcium-hydroxyapatite volume fraction in each voxel and thus the total mass of calcium in the plaque in a contrast enhanced image, potentially obviating a separate acquisition solely focused on quantification of calcium13.

Discussion

We present a novel generic spectral CT-based method for tissue-specific elemental composition analysis and quantification. Combined, detailed knowledge about anatomy and pathological tissue composition allows for quantitative disease phenotyping, with great potential for improved medical diagnosis.

In contrast to conventional CT, whereby only a limited number of different materials can be quantified or qualified, spectral CT can theoretically be used for identification and quantification of any material. Pure materials have their unique location in the XAD graph, while mixtures with varying fractions of two materials show up as line segments. The XAD graph can be used to calculate the volume fractions of two or three known base materials for each voxel.

XAD might have a great impact on medical diagnosis. For example, for the analysis of coronary vessels, the use of SCT has several advantages over CCT. With CCT two acquisitions are needed: a non-contrast-enhanced scan for calcium scoring, and a contrast-enhanced scan for stenosis visualization. Using XAD, iodinated blood can be distinguished from calcium with SCT making it possible to immediately visualize and quantify calcifications and fatty plaques on a contrast enhanced CT and could thereby obviate the need for a non-contrast CT, lowering the patient dose for this exam. In addition, it might allow for more accurate evaluation of coronary stenosis in the presence of calcified plaque as XAD allows for differentiation between calcifications and iodinated blood within the coronary artery.

The described method has limitations. It is possible that line segments of different material mixtures cross in the XAD graph, which might result in erroneous interpretations with valid volume fractions. For example, a voxel with blood and a low concentration of iodine can yield the same pair of (\(\mu _{PE},\mu _{CS}\)) values as a voxel with adipose tissue and a low concentration of calcium-hydroxyapatite. In an iodinated contrast-enhanced scan both types of voxels will be present (but in different organs), and they end up at the same location in the XAD graph. In practice, this ambiguity can be solved by limiting the XAD graph to a smaller anatomical volume of interest.

XAD graphs can be utilized to select any desired combination of base materials because, in principle, any location in the XAD graph can be decomposed into volume fractions of any two (or three) materials. To prevent ambiguities, the user should take care to pick base materials that (1) are to be expected for the anatomical location of interest and (2) are sufficiently different in chemical composition to give distinguishable locations in the XAD graph and (3) can be expected to give a complete description of the investigated tissue.

When the limitations mentioned above are taken into account, the bi-directional coupling between anatomical CT scan and material XAD graph unlocks the full potential of spectral CT.

It should be noted that the clinical examples shown in this manuscript only demonstrate the potential of the XAD technique for clinical application. Although clear pointers are given on how XAD can be used to make useful clinical applications, these applications do not yet exist. The implementation and validation of such applications will be subject of future research.

As will be shown in the Implementation section below, the construction of an XAD graph only needs two virtual mono-energetic reconstructions as input. To our knowledge, all commercially available SCT systems can produce virtual mono-energetic reconstructions and could therefore implement XAD. The computations for XAD do not warrant any special hardware requirements except for increased computer memory; compared to the analysis of a conventional CT dataset, four times more memory is needed (two input data sets, and two calculated datasets) for a straightforward implementation. With the availability of XAD graphs, dedicated applications that make use of XAD for quantification of materials can be developed too. Any implementation of XAD and any application based on XAD, will have to be certifified according to the relevant legal regulations before it can be used to aid medical diagnosis.

Implementation

Calculating (\(\mu _{PE},\mu _{CS}\))

In 1976 Alvarez and Macovski14 described that for energies relevant for medical imaging, the x-ray attenuation \(\mu\) for any material can be approximated as

In this description, only the photoelectric (PE) and Compton scatter (CS) contributions are considered. The dependencies on x-ray energy (E) and material composition (through the atomic number Z) are separated for both attenuation components. \(f_{CS}(E)\) is the well-known Klein-Nishina function, and \(f_{PE}(E) = c\times E^{-d}\), where the constants c and d should be found empirically. The functions \(a_{PE}(Z)\) and \(a_{CS}(Z)\) describe the material composition dependencies for PE and CS, respectively.

In practice it is helpful to rewrite Eq. 4 to show explicitly the attenuation coefficients \(\mu _{PE}\) and \(\mu _{CS}\) for PE and CS:

where \(E_0\) is some reference energy that can be chosen freely and

It is convenient to choose a value for \(E_0\) such that the values of \(\mu _{PE}\) and \(\mu _{CS}\) lead to values for \(HU_{PE}\) and \(HU_{CS}\) that can be related to the HU values of the conventional CT image. Since \(HU_{PE}(E_0)+HU_{CS}(E_0) = HU(E_0)\), it follows that we are looking for the energy \(E_0\) that yields a virtual mono-energetic image with HU values for relevant tissues that are most similar to the HU values of those tissues in the corresponding conventional CT image. For a 120 kV acquisition that would typically be a value between 65 and 75 keV, depending on the scanner model. Using these energy functions \(g_{PE}(E,E_0)\) and \(g_{CS}(E, E_0)\), the pair of material components \((\mu _{PE}(Z,E_0), \mu _{CS}(Z,E_0)\)) of any voxel can be calculated from two measurements of \(\mu\) at two different energies. The pair of material components are characteristic for a material, because they have distinct dependencies on only Z.

All spectral CT scanners can make virtual mono-energetic images. Scanning any phantom containing a material with a published table of x-ray attenuation coefficients at different energies, we can generate a series of virtual mono-energetic images, and use Eq. 5 to fit the constant d. Alternatively one could use the observation by Alvarez and Macovski that for all materials the energy scaling of the two components is the same, so we can just substitute the published attenuation measurements of any relevant human material from NIST databases9,10 for the functions \(g_{PE}(E,E_0)\) and \(g_{CS}(E, E_0)\). This method to decompose the SCT data into two physical attenuation components \((\mu _{PE}(Z,E_0), \mu _{CS}(Z,E_0)\)), using virtual mono-energetic images at different energies as input, is vendor independent and allows for XAD imaging of spectral CT images acquired either in projection space or in image space. Using the steps described here, we have constructed XAD graphs for SCT scanners from Siemens (SOMATOM Force and SOMATOM Flash), Philips (Spectral CT IQon and Spectral CT 7500), and GE (Revolution).

For completeness it should be mentioned that there is a third attenuation process relevant for x-ray attenuation: Rayleigh scattering. With only two measurements, it is not possible to distinguish three attenuation coefficients. However, it is still possible to use the XAD methodology if a small modification is applied: instead of using pure photoelectric absorption as one of the two components, use Rayleigh scatter plus photoelectric absorption as one component.

Custom code developed to generate XAD graphs according to our methodology is openly available on GitHub at https://github.com/asch99/XAD together with actual virtual mono-energetic images in the standard DICOM medical imaging format for demonstration.

Bidirectional interactive anatomical/XAD viewer

The authors have developed guiXAD: a working bidirectional interactive viewer with capabilities mentioned in this paper. guiXAD is part of a larger framework, used for developing applications for SCT. As such, guiXAD has many dependencies on home-grown and third party (visualization) libraries, making it infeasible for open-source publication right now. In the future, a simplified visualization tool might be added to the GitHub repository. Right now, we can demonstrate the ease of use of such a viewer in a published video, showcasing the usage of guiXAD with clinical data15.

Future directions

The XAD method as described in this manuscript uses two simultaneously acquired datasets at different energies by spectral CT scanners to calculate the contribution of the two fundamental processes that cause x-ray attenuation: Compton scattering and photoelectric absorption. With dual-energy spectral CT scanners, only two dataset are acquired, but the recently introduced photon-counting class of spectral CT scanners allows for the simultaneous acquisition of datasets at more than two energy levels. These extra energy levels could be used to extend our XAD method in two different ways.

Firstly, we could add a Rayleigh scattering term to the Alvarez-Macovski description of x-ray attenuation (Eq. 4); this could make the material identification more accurate, but it might make the interaction between CT image data and XAD material composition data more challenging.

Secondly, we could use the extra acquisition energy levels to more accurately take into account the presence of artificial contrast materials, which are often administered to the patient to boost the visibility of certain tissues. The Alvarez-Macovski model assumes that the photoelectric attenuation coefficient has the same continuous dependency on x-ray energy for all materials, but that is not the case for those special contrast materials. With dual-energy CT, care should be taken to use mono-energetic energy levels from energy ranges to which the Alvarez-Macovski model applies for these special materials. The additional acquisition energy levels of photon-counting CT could be used to modify the Alvarez-Macovski model to take the deviating behavior of contrast materials into account, making material quantification more robust.

Data availability

The patient datasets analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because these datasets were provided to the authors for illustration purposes only but the generated datasets are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Kalender, W. A. Computed Tomography: Fundamentals, System Technology, Image Quality, Applications 3rd edn. (Publicis Publishing, Erlangen, 2011).

Mileto, A. et al. Impact of dual-energy multi-detector row CT with virtual monochromatic imaging on renal cyst pseudoenhancement: in vitro and in vivo study. Radiology 272, 767–776. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.14132856 (2014).

Primak, A. N. et al. Noninvasive differentiation of uric acid versus non-uric acid kidney stones using dual-energy CT. Acad. Radiol. 14, 1441–1447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acra.2007.09.016 (2007).

Mileto, A., Nelson, R. C., Marin, D., Roy Choudhury, K. & Ho, L. M. (2015) Dual-energy multidetector CT for the characterization of incidental adrenal nodules: Diagnostic performance of contrast-enhanced material density analysis. Radiology 274, 445–454. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.14140876 (2015).

Flohr, T. G. et al. First performance evaluation of a dual-source CT (DSCT) system. Eur. Radiol. 16, 256–268. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-005-2919-2 (2006).

McCollough, C. H., Leng, S., Yu, L. & Fletcher, J. G. Dual- and multi-energy CT: Principles, technical approaches, and clinical applications. Radiology 276, 637–653. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2015142631 (2015).

Berger, M. J., Coursey, J. S., Zucker, M. A. & Chang, J. Stopping-Power & Range Tables for Electrons, Protons, and Helium Ions, NIST Standard Reference Database 124 (1998). URL http://www.nist.gov/pml/data/xcom/index.cfm. https://doi.org/10.18434/T4NC7P.

White, D., Booz, J., Griffith, R., Spokas, J. & Wilson, I. ICRU-44: Tissue substitutes in radiation dosimetry and measurement. Int. Commission Radiat. Units Meas. 54, 60–65 (1989).

Hubbell, J. H. & Seltzer, S. M. Tables of X-Ray Mass Attenuation Coefficients and Mass Energy-Absorption Coefficients, NIST Standard Reference Database 126 (1995). URL http://www.nist.gov/pml/data/xraycoef/index.cfm. https://doi.org/10.18434/T4D01F.

Berger, M. J. et al. XCOM-Photon Cross Sections Database, NIST Standard Reference Database 8 (1987). URL http://www.nist.gov/pml/data/xcom/index.cfm. https://doi.org/10.18434/T48G6X.

Stone, P. H., Libby, P. & Boden, W. E. Fundamental pathobiology of coronary atherosclerosis and clinical implications for chronic ischemic heart disease management-the plaque hypothesis: A narrative review. JAMA Cardiol. 8, 192–201. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2022.3926 (2023).

Kuneman, J. H. et al. Plaque volume, composition, and fraction versus ischemia and outcomes in patients with coronary artery disease. J. Cardiovasc. Comput. Tomogr. 17, 177–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcct.2023.02.004 (2023).

Malguria, N., Zimmerman, S. & Fishman, E. K. Coronary artery calcium scoring: Current status and review of literature. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 42, 887–897. https://doi.org/10.1097/RCT.0000000000000825 (2018).

Alvarez, R. E. & Macovski, A. Energy-selective reconstructions in X-ray computerized tomography. Phys. Med. Biol. 21, 733–744. https://doi.org/10.1088/0031-9155/21/5/002 (1976).

Schilham, A., van Hamersvelt, R. W., de Jong, P. A. & Leiner, T. Material Analysis with Spectral Computed Tomography: X-Ray Attenuation Decomposition (XAD) Imaging (2025). https://doi.org/10.34894/OKQQFJ.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.S. conceptualized the research methodology of the manuscript and created all software used and described here. A.S. and T.L. drafted the manuscript. T.L. and R.vH. and P.dJ. provided and analysed the clinical examples in this manuscript. All authors reviewed, edited, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schilham, A., van Hamersvelt, R.W., de Jong, P.A. et al. Material analysis through X-ray attenuation decomposition in spectral computed tomography. Sci Rep 15, 27714 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12640-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12640-0