Abstract

The addition of bacteria and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) is a strategy used to protect plants against disease and improve their growth and yield, known as biocontrol and biostimulation, respectively. In viticulture, the plant growth promotion (PGP) potential of bacteria endogenous to vineyard soil has been underexplored. Furthermore, most research about microbial biostimulants focuses on the effect on the plant, but little is known on how their application modify the soil and root microbial ecosystem, which may have an impact on plant growth and resistance. The objectives of this work were (1) to identify bacteria present in vineyard soils with functional PGP traits, (2) to test their PGP activity on young grapevines, in combination with AMF, (3) to assess the impact on the microbial communities and their inferred functions in the rhizosphere and plant roots. Two hundred bacteria were isolated from vineyards and characterized for their biochemical PGP activities. The most efficient were tested in vitro, both singly and in combination, on Lepidium sativum and grapevine plantlets. Two Pseudomonas species particularly increased in vitro growth and were selected for further testing, with and without two Glomus species, on grapevines planted in soil experiencing microbial dysbiosis in a greenhouse setting. After five months of growth, the co-application of PGP rhizobacteria and AMF significantly enhanced root biomass and increased the abundance of potentially beneficial bacterial genera in the roots, compared to untreated conditions and single inoculum treatments. Additionally, the prevalence of Botrytis cinerea, associated with grapevine diseases, decreased in the root endosphere. The combined inoculation of bacteria and AMF resulted in a more complex bacterial network with higher metabolic functionality than single inoculation treatments. This study investigates the effects of adding indigenous rhizobacteria and commercial fungi on the root system microbiota and vine growth in a soil affected by microbial dysbiosis. The results show a remodeling of microbial communities and their functions associated with a beneficial effect on the plant in terms of growth and presence of pathogens. The observed synergistic effect of bacteria and AMF indicates that it is important to consider the combined effects of individuals from synthetic communities applied in the field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The cultivated grapevine, Vitis vinifera L., is a perennial plant of significant global economic importance, typically propagated through grafting on Vitis rootstocks. However, this species encounters various challenges from both abiotic and biotic stressors, ultimately compromising crop yield and grape berry quality. Among the abiotic factors, drought and salinity have become increasingly prominent, exerting intensified pressure in the ongoing context of climate change1. In terms of biotic stresses, grapevine trunk diseases (GTDs), along with pests and viruses, represent major threats to viticulture due to the limited effectiveness of available countermeasures2. These factors collectively exert a detrimental impact on grapevine growth and productivity.

In response, a common practice involves replacing dead or unproductive vines with new, young ones, which requires at least 3 to 10 years post-establishment to become profitable3. During this period, young plants are exposed to environmental constraints that can significantly influence their health and development. Grapevines, like other plants, acquire most of their associated microbiota from the soil through chemoattractants exuded by the roots4. Soilborne pathogenic microorganisms, such as species from the Botryosphaeriaceae family5 or the Phaeoacremonium genus6are members of the microbial community which are attracted to and infect the root systems of both young and mature grapevines. It has also been observed that grapevine plants obtained from nurseries may harbor fungal pathogens, contributing to the decline of young vines. The infection process often occurs during the cutting and grafting preparation stages, which create numerous wounds that facilitate fungal colonization7. Infected plant material is sometimes provided by nurseries due to inadequate quality control and assessment criteria for grapevine propagation8. Besides these well-known incidences of GTDs originating from nurseries, some defects affecting the vigor and longevity of young grapevines have also been reported9. Collectively, these low-quality grapevines do not last long, and need to be replaced shortly after planting.

No comprehensive solutions currently exist to fully control soilborne pathogens that infect grapevine roots. However, several biological control strategies have been developed. The rhizosphere, defined as the narrow region of soil closely surrounding the roots, is a critical hotspot for microbe-plant interactions. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) can enhance plant development through direct nutrient transfer, hormonal regulation, or by controlling phytopathogens10. In grapevines, rhizobacteria have primarily been isolated and tested for their capacity to reduce the incidence of GTDs11. The plant growth-promoting (PGP) activities of rhizobacteria in grapevines have been assessed in vitro12 in greenhouse conditions13and in field conditions14. Interestingly, the ability of grapevine rootstocks to attract rhizobacteria with PGP traits appears to be a fundamental function, independent of vineyard location15 and rootstock genotype16.

Another noteworthy group of microorganisms with the potential to enhance grapevine growth while providing resistance to pathogens is arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF). These fungal symbionts can significantly improve plant growth by supplying essential soil nutrients to roots and controlling soilborne pathogens17. In this mutualistic interaction, the fungi provide soil nutrients such as nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) through their external mycelium in exchange for carbon from plant photosynthates released from the roots. In viticulture, AMF have been extensively studied for their beneficial nutritional traits18. Beyond nutrient uptake and pathogen inhibition, AMF are known to influence berry composition, enhancing their relevance for wine production19. It is common practice in nurseries to sell already mycorrhized grapevine plants to winegrowers.

The combination of both AMF and PGPR represents a promising strategy for pathogen control and plant growth enhancement while producing high-quality fruits20. This methodology has been applied in strawberry plants21and apple trees22but no studies have investigated the responses of grapevine microbial communities when the host is subjected to the potential synergistic effect of PGPR and AMF. Microorganisms are the fundamental drivers of biogeochemical cycles in soil, which is the microbial and nutrient reservoir for plants. Microbial inoculants are applied to restore microbial dysbiosis and enhance the growth-promoting capacity of plants23. While biosafety concerns have been consistently evaluated concerning human healthcare and plant health, the impact of microbial applications on the indigenous microbiome and plant phenotypic traits is seldom considered24.

The first aim of this study was to characterize the plant growth-promoting activity of 200 rhizobacteria isolated from the rhizosphere of grapevines showing symptoms of decline, as well as from asymptomatic plants, from a specific vineyard25. The second objective was to test the ability of the best combination to promote grapevine plant growth in a soil with microbial dysbiosis (characterized by a higher abundance of latent fungal pathogens and potentially beneficial bacteria with lower diversity and richness compared to asymptomatic soil25). Subsequently, the most effective PGPR combination was used to inoculate both mycorrhized and non-mycorrhized young grafted grapevines in a greenhouse to observe its effects on grapevine development and root microbiota.

Material and methods

Screening for in vitro PGP activities of bacterial isolates

A subset of 200 isolates was randomly chosen from a pool of 800 rhizobacteria previously isolated26. This selection comprised 50 isolates from the rhizosphere of two rootstocks (Riparia Gloire de Montpellier (Vitis riparia) or 1103 Paulsen (Vitis berlandieri x Vitis rupestris)) grown in soils from either symptomatic or asymptomatic areas. These selected isolates were tested for six PGP activities.

Indole-3-Acetic acid (IAA) production

The production of IAA was determined using the Salkowski reaction adapted from Gordon & Weber (1951)27. The bacterial isolates were grown in LB medium supplemented with 100 µg.ml−1 l-tryptophan, acting as a precursor for IAA synthesis, for 48 h at 28 °C under continuous shaking at 200 rpm. Bacterial suspensions were centrifuged at 8000 g for 10 min at 4 °C. One ml of the supernatant was then mixed with 4 ml of Salkowski reagent (1 ml of 0.5 M FeCl3 in 50 ml of 35% HClO4), followed by measuring the color changes using a spectrophotometer at 530 nm. The calibration curve for estimating auxin concentration was made with standards ranging from 10 to 100 µg.ml−1 of IAA.

1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate deaminase (ACCd) deaminase activity

The presence of ACCd activity was determined using ACC as sole source of nitrogen, following the method adjusted from Penrose & Glick (2003)28which estimates the amount of α-ketobutyrate produced. Cells initially grown in R2A medium were inoculated at OD600 = 0.1 in DF medium supplemented with 3 mM of ACC and incubated at 30 °C for 48 h. After centrifugation at 8000 g, pellets were washed with 0.1 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.6) and resuspended in 600 µl of 0.1 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.5) amended with 30 µl of toluene, and vortexed for 30 s. Two hundred µl of toluenized cells were gently mixed with 0.5 M ACC and incubated at 30 °C for 15 min. The reaction was stopped by adding 1 ml of 0.56 M HCl and vortexed, followed by a 5-minute centrifugation at 16,000 g. One ml of supernatant was mixed with 800 µl of 0.56 M HCl and 300 µl of 2,4 dinitrophenylhydrazine (0.2% in 2 M HCl), and incubated at 30 °C for 30 min. Colorimetric reactions occurred with the addition of 2 ml of 2 N NaOH and were measured at 540 nm. The calibration curve for estimating ACCd concentration was made with standards ranging from 0.1 to 1 µg.ml-1 of α-ketobutyrate.

Ammonia production

The production of ammonia for each rhizobacteria was assessed using the Nesslerization reaction described by Cappuccino & Sherman (1992)29. Each rhizobacterial isolate was grown in peptone water for 72 h at 28 °C at 200 rpm. Culture supernatant (200 ml) was mixed with 1 ml of Nessler’s reagent which was supplemented with 7.3 ml of ammonia-free water. The development of brown to yellow color indicating ammonia production was spectrophotometrically monitored at 450 nm. The calibration curve for estimating ammonia concentration was made with standards ranging from 0.1 to 1 µmol.ml−1 of ammonium sulphate.

Siderophore synthesis

The synthesis of siderophores was determined using the plating method based on Chrome-azurol S (CAS) medium adjusted from Schwyn & Neilands (1987)30. The CAS assay solution consisted in 6 ml of 10 mM HDTMA solution diluted up to 100 ml with distilled water and a mixture of 1.5 ml iron (III) solution (1 mM FeCl3·6H2O in 100 mM HCl) supplemented to 7.5 ml of 2 mM aqueous CAS solution which was added under stirring. Anhydrous piperazine (4.307 g) was dissolved in 30 mL of water, and 6.25 ml of HCl (37%) was carefully added to it. This buffer solution (pH 5.6) was adjusted to 100 ml and the CAS shuttle solution was obtained by adding 4 mM of 5-sulfosalicylic acid to the above solution. Bacterial isolates were plated on CAS agar and incubated for 72 h at 28 °C. Siderophore production was assessed by measuring the distance between the colony and the edge of its surrounding halo.

Phosphate solubilization

The ability of the rhizobacteria to solubilize phosphate was determined using the Pikovskaya medium31. Each bacterial isolate was plated on Pikovskaya agar (1% glucose, 0.5% Ca3(PO4)2, 0.05% (NH4)SO4, 0.02% NaCl, 0.01% MgSO4.7H2O, 0.02% KCl, 0.0002% MnSO4.7H2O, 0.0002% FeSO4.7H2O, 0.05% yeast extract, 1.5% agar) supplemented with bromophenol blue to assess phosphate solubilization capacity. Plates were incubated for 72 h at 28 °C. Phosphate solubilization was assessed by measuring the distance between the colony and the edge of its surrounding halo.

Nitrogen fixation

The capacity of the isolates to fix nitrogen was assessed with the NfB solid medium adjusted from Döbereiner (1989)32. Each bacterial isolate was plated on pH 6.8 NfB (0.05% D-malic acid, 0.05% K2HPO4, 0.02% MgSO4, 0.01% NaCl, 1.5% agar) complemented with 2 ml of bromothymol blue (0.5% in 0.2 M KOH), 1 ml of vitamin solution (per 100 ml: 10 mg biotin, 20 mg pyridoxine-HCl), and 2 ml of micronutrient solution (per litter: 40 mg CuSO4.5H2O, 120 mg ZnSO4.7H2O, 1.4 g H3BO3, 1 g Na2MoO4.2H2O, 1.5 g MnSO4.H2O). Plates were incubated for 72 h at 28 °C. Nitrogen fixation was assessed by measuring the distance between the colony and the edge of its surrounding halo.

Identification of the most promising strains

Isolates exhibiting the most efficient PGP activities were subjected to sequencing of their 16S rRNA gene to confirm their identities. DNA extraction from isolates was performed using the FTA® CloneSaver™ card (Whatman® BioScience, USA), as described by Zott et al. (2008)33. Extracted DNA was used as template for PCR amplification specific primers for the 16S rRNA gene, namely 8F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′) and 1063R (5′-ACGGGCGGTGTGTRC-3′), as described by Martins et al. (2020)34. The 16S rDNA sequences obtained were deposited in the GenBank Database under accession numbers ON159710 to ON159717.

in vitro evaluation of growth promotion on Lepidium sativum

Seeds of Lepidium sativum were surface sterilized by immersion in 2.5% sodium hypochlorite for 1 min followed by an immersion in 3% H2O2 for 1 min. Afterwards, seeds were rinsed thrice with sterile distilled water. Sterilization was confirmed by macerating fifteen seeds in sterile 0.86% NaCl and plating 100 µl of the macerate on R2A medium. Subsequently, seeds were plated on water agar and incubated for 24 h at 25 °C. Fifteen pre-germinated seeds with uniform radicles length (1.5–2 mm) were then selected and placed on new water agar dishes. The eight selected PGPR were inoculated in single, dual, or triple combinations, resulting in 92 unique combinations. Each was applied in 100 µL of water-based solution at a final concentration of 109 CFUs.ml−1. The control was considered as a treatment with sterile water only. Plates containing the inoculated pre-germinated sterilized seeds were incubated for 72 h at 25 °C. To assess the capacity of PGPR to promote L. sativum growth, the length and the fresh biomass of stems and roots were measured.

in vitro evaluation of growth promotion on 1103P plantlets

Grapevine plantlets 1103P were propagated in vitro on McCown Woody Plant Medium (Duchefa) supplemented with 3% sucrose, 0.27 µM 1-naphthalene acetic acid, and 0.75% agar. The propagation was conducted in a growth chamber set to a temperature of 25 °C during the day and 20 °C at night, with a photoperiod of 16 h light and 8 h dark with a light intensity of 145 µmol photons m–2 s–1. After six weeks of growth, fifteen plantlets were transplanted into pots filled with McCown Woody Plant Medium containing 0.5% agar, without any additional supplements. The eight selected PGPR were inoculated in single or dual combinations, resulting in 36 unique combinations. Each combination was applied in 300 µL of water-based solution at a final concentration of 109 CFUs.ml−1, targeting the basal part and root extremities of the plantlets. The control was treated with sterile water only. To evaluate the ability of PGPR to promote plantlet growth, both length and fresh biomass of stems and roots were measured four weeks post-inoculation. Additionally, the number of primary and secondary roots was counted, and petiole length was measured.

Greenhouse experiment to evaluate the effect of the application of rhizobacteria and/or AMF on grapevine grafted plants

A schematic summary of the greenhouse disposal, samplings, and measurements conducted during this study is depicted in Supplementary Fig. S1. Eighty grapevines were obtained from the nursery Pépinière Guillaume (70700, Charcenne, France) as grafted V. vinifera L. cv. Cabernet Sauvignon (CS) scion clone 169 onto 1103P rootstock. This grapevine combination was produced from traditional bare-root plants. Half of those plants were mycorrhized by the nursery with the commercial tablet AEGIS SYM™ from Atens (La Riera de Gaià, Spain). The inoculum consisted of a mixture of polysaccharides and Rhizophagus irregularis strain BEG72 (former Glomus intraradices) and Funneliformis mosseae (former Glomus mosseae). Approximatively 200 spores per plant were applied to the grapevine roots. Twenty mycorrhized plants and another twenty non-mycorrhized plants were separately inoculated by dipping the roots overnight in the 109 CFUs.ml−1 bacterial solution (Pseudomonas veronii and P. brassicacearum) suspended in water. It results in twenty plants for each treatment (i.e., untreated, mycorrhized, bacterized, and both mycorrhized and bacterized). These plants were put in 7.5 L pots (diameter 26 cm, height 21 cm) filled with the soil excavated (0–30 cm from the surface, sieved to 3 mm) from the symptomatic area of a vineyard described in Darriaut et al. (2024)25. The plants were grown in greenhouse under ambient light and temperature. They were watered twice a week with 60 ml per pots with no nutrient supply. Plants were harvested after 5 months of growing (from mid-April to mid-September). The following parameters were assessed: aerial fresh biomass, including leaves and shoots; fresh biomass of trunks and roots; and diameter and length of shoots and trunks. Chlorophyll contents of the top fourth and third leaves were measured using a portable chlorophyll meter (SPAD-502, Konica Minolta Sensing, Inc., Japan). The dry biomass of total leaves, stems, trunks, and roots was evaluated after drying at 70 °C for 72 h.

Roots, rhizosphere, and bulk soil were also collected. Roots were removed from soil aggregates by manual shaking, and approximately 5 g of roots were put in tubes containing sterile 0.85% NaCl solution and vortexed prior to 5,000 g centrifugation for 10 min to separate the rhizosphere from the roots.

At this stage, half of each root samples was surface sterilized with 3% sodium hypochlorite for 1 min subsequently to 3% H2O2 for 1 min and rinsed thrice using sterile water. Three randomly selected samples were merged to create a total of three pools. These sterilized roots were stored at −80 °C prior to DNA extraction. The second half of fresh roots was used for staining to observe endomycorrhizal structures.

Rhizosphere samples obtained after centrifugation were also separated into two subgroups. Similar to root pooling, three randomly selected rhizosphere samples were pooled to create a total of three pools. The first subgroup of rhizosphere samples was lyophilized for 48 h using Christ Alpha® 1–4 (Bioblock Scientific) and stored at −80 °C prior to DNA extraction. The second subgroup was used for the measurement of the potential metabolic diversity (PMD), the isolates quantification with plating method, as well as the isolates identification through MALDI-TOF MS.

Analysis of microbial functional diversity and composition through potential metabolic diversity (PMD), root staining for mycorrhizal colonization, qPCR and MALDI-TOF MS

PMD, quantification of cultivable bacteria and fungi from fresh rhizosphere, and quantitative PCR of bacterial 16S, archaeal 16S, and fungal 18S from lyophilized rhizosphere were performed according to Darriaut et al. (2021)35. This involved plating soil dilutions on R2A medium amended with 25 mg.l−1 of nystatin to quantify the cultivable bacterial population while quantifying the fungal populations were on PDA medium supplemented with 500 mg.l−1 of gentamicin and 50 mg.l−1 of chloramphenicol.

PMD was evaluated on the three rhizosphere pools using Biolog Eco-Plates™ system (Biolog Inc., CA), by measuring 31 different substrates (i.e., amines, amino acids, carbohydrates, carboxylic acids, phenolic compounds, and polymers) consumed by present microorganisms, every 24 h for 4 days.

From the subgroup of fresh root samples that were not surface-sterilized, 30 subsamples of fresh roots were utilized to assess their colonization by AMF. These roots were stained using the modified ink-KOH-H2O2 method, and AMF colonization was estimated as described by Darriaut et al. (2022)26.

Quantitative PCR analyses based on absolute quantification were performed on the DNA extracted from rhizosphere using three primers pairs to quantify bacterial (341F/515R) and archaeal 16S rRNA (Arch967F/Arch1060R) genes as well as the fungal 18S rRNA (FF390/FR1) gene, listed in Supplementary Table S1. The efficiencies of the qPCR were ranging from 80 to 99% (R² > 0.99).

The identification of bacterial isolates from the fresh pools of rhizosphere was performed using MALDI-TOF MS technology according to Darriaut et al. (2022)26.

Metabarcoding of 16S and 18S rRNA genes and ITS sequencing and bioinformatic analysis

Total DNA was extracted from the root endosphere, the rhizosphere and the bulk soil as described in Darriaut et al. (2024)25. The DNA samples were randomized across plates and amplified using the universal primers, including the specific overhang Illumina adapters from Darriaut et al. (2023)36 listed in Supplementary Table S1, specific to either the bacterial and archaeal 16S rRNA gene (785R/341F), the fungal 18S rRNA gene (AMV4.5Nf/AMDGr) or the fungal ITS1 region (ITS1F/ITS2). The functional inferences of bacterial and fungal communities were performed using PICRUSt2 and FUNGuildR as in Darriaut et al. (2024)25.

Statistical analyses

All analysis and graphs were performed on R (R-4.2.1) using RStudio (2022.07.1). Figures were generated with ggplot2 (3.5.0) and ggthemes (5.1) packages and arranged using ggpubr (0.6.0).

One-way ANOVA or Kruskal-Wallis and pairwise comparison using Student t or Wilcoxon tests were performed on the total biomasses and length from L. sativum and 1103P plantlets inoculated with the different bacterial consortia. To classify the growth potential of consortia, “hclust” function from stats (4.2.1) was performed to cluster groups together in a circular plot based on Euclidean distance with the Wards’s minimum variance method (Ward D2).

Two-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) with treatment (untreated, bacterized, mycorrhized, both bacterized and mycorrhized) and compartment (bulk, rhizosphere, and root endosphere) factors were performed on cultivable, q-PCR, Eco-Plates measurements, and abundances of functional OTUs. Residuals were checked for their independency, normality, and variance homogeneity with the Durbin Watson, Shapiro-Wilk, and Bartlett tests, respectively. When assumptions for parametric tests were not respected, a multiple pairwise comparison using Wilcoxon test was performed subsequently to Kruskal–Wallis test using the multcomp (1.4–25) package. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was performed using FactoMineR (2.9) and missMDA (1.19). Area under curve (AUC) of average color well development (AWCD) which better explain curve dynamics, was calculated with the trapezoidal method for each condition using caTools (1.18.2). Regarding amplicons analyses, shared OTUs were visualized with Venn diagrams generated with the VennDiagram (1.7.3) package. Richness and α-diversity metrics, represented by Chao1, Simpson’s diversity, and Bray-Curtis dissimilarity, respectively, were calculated through phyloseq (1.42.0) using “estimate_richness” and “distance” functions. In order to test for significant differences between the means of alpha diversity metrics by conditions, pairwise comparisons were used, based on either t or wilcoxon test, subsequently to homogeneity and normalization verifications using Levene and Shapiro tests. Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) was used to ordinate samples in two-dimensional space based on Bray-Curtis distance using ordinate function from phyloseq with “NMDS” method. Linear models and permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA), for richness and diversities metrics, were demonstrated using the formula: variable ~ Treatment × Compartment. Type-II ANOVAs were performed using car (3.1-2) on Chao1 and Simpson’s diversity metrics while PERMANOVAs were assessed on Bray-Curtis dissimilarity using “adonis2” function from vegan with 999 permutations. Functions “ggeffectsize” and “ggdiffbox” from MicrobiotaProcess (1.10.3) were used to discriminate significantly different taxa across conditions. This process was set with Kruskal (α = 0.05) test based on linear discriminant analysis (LDA) effect size (LEfSe) and Wilcox (α = 0.05), corrected with False Discovery Rate (FDR). Co-occurrence networks were set up for 16S rRNA and ITS communities within root system (both rhizosphere and root endosphere) using “trans_network” from microeco (1.4.0). Spearman’s correlation was estimated using WGCNA (1.72-5) with a 0.001 threshold. The “cor_optimization” function retrieved the optimal coefficient threshold and “COR_p_thres” value was set up to 0.05. Ecological modules, a cluster of nodes highly interconnected, were determined using the greedy optimization from “cal_module”. The networks were visualized using Gephi software (0.10.1). Network properties were extracted with “cal_network_attr”, and network stability indexes were estimated using “robustness” (10 run) and “vulnerability”. The Z-score evaluating within module connectivity, and P-score assessing among module connectivity, of the nodes were calculated using “plot_taxa_roles” to identify keystone species. The hubs defined as module hub nodes (Z-score > 2.5 and P-score ≤ 0.62) and connector nodes (Z-score ≤ 2.5 and P-score > 0.62) were considered as keystone taxa.

Results

Identification of vine rhizobacterial isolates with biochemical PGP activities

Based on previous MALDI-TOF MS analyses2635% of the 200 rhizobacterial isolates randomly selected were not identified, while the other isolates were classified into 17 distinct genera, as shown in Fig. 1A. Each of the 200 rhizobacterial isolates exhibited at least one of the six plant growth-promoting (PGP) traits, including isolates obtained from the rhizosphere of declining grapevines. ACC deaminase was the least common PGP trait (15%), while the most common was siderophore production (55.5%), followed by nitrogen fixation (55%), ammonia production (54.5%), IAA synthesis (49%), and phosphate solubilization (48%). The genera exhibiting functional capabilities related to the six PGP traits included Bacillus, Burkholderia, Enterobacter, Pseudomonas, and Rhizobium.

Plant growth-promoting (PGP) capacity of the 200 bacteria isolates from the grapevine rhizosphere to produce ammonia, indole acetic acid, ACC deaminase, and siderophore, to solubilize phosphate, and to fix atmospheric nitrogen. (A) Distribution of the PGP activities according to the genera previously identified using MALDI-TOF MS. When a PGP activity was detected, it was considered as an occurrence within the distribution graph (i.e., one isolate can have several PGP activities). (B) The eight most promising isolates identified using sequencing, and selected for in vitro growth promotion assays on Lepidium sativum and 1103P plantlets. (+++) indicates that the isolate was the most effective within the considered PGP function. (++) indicates that the isolate was among the top 50% most effective. (+) indicates that the isolate was among the 50% least effective. (-) indicates a non-effective isolate in the corresponding PGP function.

This biochemical screening led to the selection of eight isolates (Fig. 1B): the top performer for each PGP trait (isolates A to F) and two isolates showing broad-spectrum activity across all traits (isolates G and H). Sequencing identified five Pseudomonas isolates, two Enterobacter and one Rhizobium isolate.

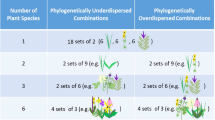

Growth promotion effects on Lepidium sativum and Vitis plantlets of selected rhizobacteria

To confirm the effect of these isolates on plant growth, a first screening was done in vitro. Lepidium sativum seeds and 1103P plantlets were inoculated with the eight selected isolates either single or in co-application (double and/or triple inoculations) (Supplementary Tables S2 and S3). Lepidium enables rapid screening of numerous combinations, whereas grapevine assays involve considerably more preparation. Phenotypic traits of the inoculated plants were measured and compared with those of water-treated plants.

For L. sativum, among the 92 tested combinations, 98% increased stem mass, 76% enhanced root length, 76% increased root biomass, and 61% enhanced stem length compared to water-treated controls (Supplementary Table S2). For 1103P, among the 36 tested combinations, 61% increased leaf and stem mass, while 47% increased stem length (Supplementary Table S3). Regarding the root system of grapevine plantlets, 78% of the combinations promoted root mass, 70% enhanced the length of secondary roots and 39% increased the length of primary roots.

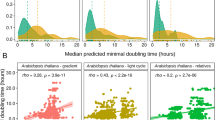

A PCA biplot was used to better visualize the effects of inoculants on the phenotypic traits measured in L. sativum, and grapevine 1103P rootstock (Fig. 2A). This multivariate analysis revealed a different response pattern between the two species. The HCA dendrogram, based on phenotypic similarities of the samples, provides complementary insights to the PCA biplot, and allows the identification of seven and five clusters for L. sativum and 1103P rootstock, respectively (Fig. 2B). In both L. sativum and 1103P, individual inoculations of single strains generally resulted in limited or non-significant effects (Fig. 2A and B). Moreover, in co-inoculations, no strain exhibited a consistently positive or negative effect across all combinations, indicating that the outcome depends strongly on the identity of the co-inoculated strains. In L. sativum, dual inoculations tended to produce weaker effects compared to triple inoculations, with some exceptions of combinations such as A×C. Among the triple combinations, both positive and negative phenotypic effects were observed in nearly equal proportions.

Growth promotion effects of potentially beneficial isolates on Lepidium sativum sprouted seeds (n = 15) and 1103P plantlets (n = 15). (A) Biplot PCA of several growth traits from aerial and root systems. PCA individuals were colored according to their inoculation type (single, double, triple, water, or mix, with the latter combination standing for the eight-isolate consortium). (B) HCA of the different consortia based on phenotypic measurements. Clusters were color-coded based on the gradient of efficiency of isolates in influencing growth, with symbols (+), (++), (+++), and (++++) denoting promotion, and (-) and (--) indicating inhibition compared to conditions treated with water. (Water-like) indicates that the cluster inoculants had the same effect on plant growth as water treatment. (C) Influence on the total length and biomass (stem and root) of single inoculants and consortia composed of two or three different isolates compared to water treatment, with the latter triple-combination exclusively performed on L. sativum. Different letters indicate that the groups have a mean difference that is statistically significant (P < 0.05).

To compare the growth-promoting effects of various inocula on L. sativum and 1103P plantlets, Fig. 2C presents the results for total biomass and plantlet length for single and dual inoculations. Significant differences were observed among the different inoculation treatments. The combination that produced the greatest positive effect on L. sativum development was A×C, while A×C and A×B were the most effective for 1103P plantlets (Fig. 2B and C). Based on the results, the A×C consortium, composed of P. veronii and P. brassicacearum, was selected for subsequent greenhouse experiments on young grapevine bare-root plants.

One remaining question is whether the effects of the bacterial consortia are correlated across different plant species. In this study, cross-species correlation analysis revealed a significant but moderate overall correlation between the growth responses of L. sativum and grapevine (R = 0.286, R² = 0.082, P = 2.01e-05) (Supplementary Figure S2.A). Variable-specific analysis showed that total length exhibited the strongest cross-species correlation (R² = 0.021, P = 0.40), followed by aerial fresh weight (R² = 0.018, p = 0.43), while root fresh weight showed the weakest correlation (R² = 0.001, P = 0.83) (Supplementary Figure S2.B). Performance ranking analysis indicated no significant correlation between species-specific rankings of microbial combinations (Spearman ρ = 0.079, P = 0.646) (Supplementary Figure S2.C), suggesting that top-performing combinations in one species may not necessarily be the best performers in another. Individual combination analysis revealed substantial variation in cross-species consistency, with some combinations showing strong positive correlations (R² > 0.5) while others exhibited negative correlations, indicating species-specific responses to certain microbial treatments (Supplementary Figure S2.D). These findings highlight the importance of species-specific validation when developing microbial inoculants for different plant hosts.

Assessment of the impact of three microbial consortia on grafted grapevine in greenhouse

As described above, the two isolates A and C (P. veronii and P. brassicarearum, respectively) were selected and used to inoculate bare-root 1103P plants potted in symptomatic soil undergoing microbial dysbiosis (described as symptomatic soil in Darriaut et al. (2024)25). The phenotypic data of the four treatments (i.e., untreated, mycorrhized, bacterized, and both mycorrhized and bacterized) are detailed in Supplementary Table S4. After two months in the greenhouse, no significant differences could be detected; but, five months after treatment, the plants co-inoculated with bacteria and fungi showed a significantly greater dry root biomass compared to the three other treatments (F(3, 36) = 2.27, P = 0.047). A significantly higher branch diameter was observed in untreated vines and vines treated with rhizobacteria compared to the mycorrhized plants (χ 2 = 21.0, P < 0.001). This result is consistent with the results found in vitro, which showed that this combination of Pseudomonas isolates was able to promote root biomass.

Rhizosphere microbial profiles of five-month-old grafted grapevines, assessed by cultivable methods and qPCR

To evaluate the impact of the treatments on the microbial profile of the belowground part, the rhizosphere was first analyzed using MALDI-TOF MS and q-PCR for each treatment at the end of the experiment. Sixty-three different species were identified (Supplementary Figure S3) belonging to 26 distinct genera, while unidentified genera accounted for 28% of the isolates (Fig. 3A). The four treatments exhibited six core genera, belonging to Bacillus (22%), Pseudarthrobacter (9%), Pseudomonas (8%), Paenarthrobacter (2.5%), and Paraburkholderia (5%) (Fig. 3B). Some genera such as Rhizobium, Methylobacterium, and Microbacterium were detected only in mycorrhized conditions, while Lysinibacillus was only found in conditions inoculated with rhizobacteria, and Flavobacterium was unique to untreated conditions. The α-diversity of cultivable rhizobacteria, represented by the Simpson’s diversity and Shannon indexes (Fig. 3A), was highest when grapevines were inoculated with both AMF and rhizobacteria (Fig. 3C). Conversely, the lowest α-diversity was found in mycorrhized, followed by untreated and bacterized conditions.

Microbial profile of the rhizosphere compartment of grapevines grown five months in a greenhouse, under untreated, mycorrhized, bacterized, and mycorrhized-bacterized conditions. (A) MALDI-TOF MS identification of the top ten most abundant rhizobacteria, associated with the Simpson’s Diversity and Shannon indexes (n = 150). The less abundant genera were grouped in ‘Others’. (B) Venn diagram illustrating the overlap of the identified genera. (C) Cultivable dependent methods analysis related to the level of cultivable bacteria and fungi, and to the mycorrhizal associations with roots under microscopic observations. (D) Molecular dependent methods analysis related to the extracted DNA associated with the number of gene copies (i.e., 18S, archaeal and bacterial 16S). Different letters indicate that the groups have a mean difference that is statistically significant (P < 0.05).

The samples treated with the combined inoculation presented significantly lower levels of cultivable bacteria and fungi compared to other single inoculation and untreated conditions (Fig. 3C). While mycorrhizal frequency on roots showed no significant differences between treatments, mycorrhizal intensity was significantly higher in the mycorrhizal treatment compared to the bacterial treatment (Fig. 3C).

The quantity of total DNA in the rhizosphere was significantly higher in bacterized samples compared to the mycorrhized condition (Fig. 3D). While the quantity of 16S rRNA gene and ITS was not significantly changed among the treatments in the rhizosphere, unexpectedly fungal 18S rRNA gene quantity was significantly lower in samples treated exclusively with AMF. Taken together these data suggested some little differences in the microbial communities between the treatments.

Treatments did not have a strong influence on the composition of belowground microbial communities

To further investigate the root-associated microbial community after five months of treatment, sequencing was performed on the root endosphere, rhizosphere, and bulk soil. A total of 5,878,244 raw sequences were generated from the libraries run. After chimera removal, paired-end sequences were clustered into 2,684 16S rRNA, 860 ITS, and 275 18S rRNA operational taxonomic units (OTUs).

OTUs shared among the three compartments were 77%, 69% and 27% of the total OTUs based on 16S rRNA, ITS, and 18S rRNA gene sequencing, respectively (Supplementary Figure S4). Similarly, 89%, 75%, and 33% of OTUs were shared across the four treatments (i.e., untreated, mycorrhized, bacterized, and mycorrhized-bacterized), respectively.

The percentage of relative abundance of the bacterial, fungal and mychorrhizal phyla in rhizosphere and roots depending on the treatment is shown in Fig. 4A. The results for the bulk soil samples are presented in Supplementary Figure S5. Globally, the most abundant phyla were in accordance with those found in the vineyard25. As expected, the composition of the microbial community was different depending on the compartment studied between root and rhizosphere (Fig. 4). No clear significant effect of the treatment was found for the rhizosphere microbial indexes not for the bulk soil (Supplementary Figure S5). Root endosphere bacterial richness (Chao1) was lower in dual-treated roots compared to other treatments. In addition, the root endosphere samples treated with both AMF and rhizobacteria displayed lower diversity in ITS communities compared to the bacterized treatment.

Microbial composition metrics of bacterial (16S rRNA gene), fungal (ITS), and Glomeromycota (18S rRNA gene) communities across the root and rhizosphere compartments in untreated, mycorrhized (Myc), bacterized (Bac), and mycorrhized-bacterized (Myc + Bac) samples. (A) Relative abundances, (B) Chao1 richness, (C) Simpson’s diversity Index, and (D) NMDS based on Bray-Curtis dissimilarities with the associated ANOVA and PERMANOVA (perm = 999) tests. ANOVA and PERMANOVA tests are displayed with treatment (= T) and compartment (= C) effects. Different letters indicate that the groups have a mean difference that is statistically significant (P < 0.05).

The LEfSe (P < 0.05, FDR, LDA > 1.5) detected enriched genera within rhizosphere (Supplementary Figure S6.A) and root (Supplementary Figure S6.B) compartments for both 16S rRNA and ITS-based communities, while none were related to 18S rRNA communities. In particular, the Pseudomonas genus was enriched in the co-inoculated roots compared to the other treatments. Botrytis was enriched in non-inoculated 1103P plants which was previously found in previous studies26.

Treatments induced distinct microbial co-occurrence networks within root systems

Co-occurrence networks of bacteria and fungi within the root system, encompassing the rhizosphere and root endosphere, provide insights into the impact of microorganism additions on bacterial (Fig. 5A) and fungal (Fig. 5C) interactions.

Ecological network analysis for bacterial and fungal communities within root systems (root and rhizosphere combined). Co-occurrence networks of the (A) 16S rRNA and (C) ITS-based communities among untreated, mycorrhized, bacterized, and mycorrhized-bacterized conditions. Different node colors refer to different OTUs according to their phyla, and edge colors represent significant positive (red) and negative (green) correlations (r > 0.70; P < 0.05). The role of OTUs in the network of (B) bacterial and (D) fungal communities was determined according to within-module connectivity (Zi) and among-module connectivity (Pi). Keystone taxa were determined when Pi > 0.62 (connector node) and Zi > 2.5 (module hub node).

The network was simpler for the fungal communities (coefficient clustering: 0.777 to 0.850) compared to the bacterial ones (coefficient clustering: 0.598 to 0.803) (Table 1). Among the bacterial communities, the interaction networks increased in complexity, represented by the nodes and edges, when the grapevines were bacterized (+ 0%, + 64%), mycorrhized (+ 9%, + 230%), and both bacterized and mycorrhized (+ 13%, + 559%), compared to untreated samples. Although the nodes and edges of fungal co-occurrence networks were simpler in mycorrhized (−21%, −58%), and bacterized (+ 7%, −16%) conditions compared to untreated samples, they gained in complexity (+ 36%, + 22%) in the mycorrhized-bacterized condition, indicating a synergistic effect of the co-inoculation.

Network stability, evaluated by robustness and vulnerability, was greater in bacterial communities, especially in mycorrhized-bacterized conditions compared to other conditions (Supplementary Figure S7). However, fungal network stability presented high robustness and high vulnerability for the untreated condition compared to treated samples. Irrespective of the treatment, based on Z-scores (within-module connectivity) and P-scores (among-module connectivity), 2 and 27 OTUs within these co-occurrence networks were identified as module hubs and connectors, respectively, for bacterial communities (Fig. 5B), and 0 and 9 OTUs for fungal communities (Fig. 5D). The Zi score identified Fonticella and Acidobacteriales as keystone taxa for the untreated condition and combined treatment of both AMF and bacteria respectively. The Pi score detected more keystone taxa within both bacterial and fungal networks in the mycorrhized-bacterized condition compared to the untreated one. Samples treated only with mycorrhizal fungi presented 10 bacterial OTUs as connectors while none were detected for fungal networks. Furthermore, no keystone taxa were detected for the bacterized treatment.

Microbial addition had an impact on the metabolic functions of microbial communities

PMD, based on the consumption of various carbon substrates after 96 h of EcoPlates incubation, revealed an increase in global metabolic activity of the mycorrhized-bacterized rhizosphere (Fig. 6A). From the consumed substrates, it appeared that the increased metabolic activities were mostly due to carbohydrates and carboxylic acids, with enhanced activity for the combined mycorrhized and bacterized treatment compared to the untreated condition.

Potential activities of the root and rhizosphere microbiomes in untreated, mycorrhized, bacterized, and mycorrhized-bacterized samples. (A) EcoPlates measurements in the rhizosphere compartment, associated with the different family compounds measured 96 h after incubation. Functional inference of the (B) 16S rRNA gene using PICRUSt2 and (C) ITS gene using the FUNGuild database. Different letters indicate that the groups have a mean difference that is statistically significant (P < 0.05). Significant P values of the ANOVA are displayed in bold.

Potential metabolic pathways based on 16S rRNA gene sequences were inferred using PICRUSt2. The 2,269 predicted clusters were assigned to 19 pathways among the ‘Cellular Processes’, ‘Metabolism’ and ‘Environmental Information Processing’ classifications (Fig. 6B). Significant differences were found in the rhizosphere with a higher abundance of bacteria related to the metabolism of xenobiotics, carbohydrates, and amino acids from plants co-inoculated with bacteria and AMF, compared to the other treatments. Additionally, the rhizosphere and root endosphere of co-inoculated plants showed less abundance in fungal saprotrophs as identified using FUNGuild (Fig. 6C). Altogether, these results indicate that the most pronounced effect on the predicted microbial community functions was induced by the co-inoculation of the two Pseudomonas isolates with AMF.

Discussion

Stressed plants as a potential reservoir of rhizobacteria with PGP traits

In addition to signaling compounds exudated from roots, environmental stimuli can modulate biochemical functions of microorganisms. For example, the composition and production of exopolysaccharides or anti-oxidative enzymes in cyanobacteria under salt stress are modified37,38. In previous studies, the PMD measured by EcoPlates technology was greater in the symptomatic bulk35 and rhizosphere25 soils experiencing grapevine decline compared to asymptomatic ones. Therefore, one hypothesis would be that the grapevine under decline produces compounds stimulating the microbial communities in the surrounding soil, and that the high abundance of fungi potentially associated with grapevine diseases creates a niche for beneficial bacteria. Ethylene, a plant hormone that coordinates stress signaling within the host, is produced due to various environmental stimuli39. Among the different PGP traits, ACC deaminase is known to alleviate ethylene’s adverse effects on plant development40. Strains possessing the highest efficiency in ACC deaminase have been isolated from nutrient-poor and alkaline areas41. Similarly, the best siderophore producers have been isolated in the rhizosphere of tolerant cultivar under iron stress42. The best candidates for phosphate solubilization, nitrogen fixation, siderophore, and IAA synthesis, identified as Pseudomonas syringae, Pseudomonas koreensis, Pseudomonas veronii, and Enterobacter cloacae respectively, were all isolated from symptomatic soils26. Studying isolates in stressed environments could be an interesting goal to pursue, especially in the root endosphere or the rhizosphere of symptomatic plants which may harbor highly active and beneficial microbes.

From microbial screening to application of efficient inoculants for grapevine

Exploring grapevine and soil microbiomes not only highlights the mechanisms governing the assembly and dynamics of plant-associated microbial communities but also offers strategic guidance to enhance grapevine fitness and promote sustainable viticulture based on microbiome engineering43. Transposing results from artificial environments to living host plants is essential to the success of probiotic development. Deployment of consortia may confer more efficient growth promotion than single strain application44which is consistent with our findings. The preliminary selection of potentially plant growth-promoting bacteria was conducted using Lepidium, a fast-growing model plant, followed by in vitro-grown grapevine rootstock plantlets. The selected bacterial strains induced root biomass increases of 124% in Lepidium and 41% in 1103P plantlets. Under greenhouse conditions, co-inoculation with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) alongside the two bacterial strains was required to achieve a 26% increase in root biomass compared to the untreated control. Extending the experiment over a full growing season would likely have been necessary to observe a stronger effect in grapevines. Pseudomonas species have already been reported to promote growth of crop roots in laboratory45 and greenhouse46 environments. Although few grapevine studies exist in situ14the exploration of plant growth enhancement is not as extensively developed as the research on biological control47. Pseudomonas isolated from wood tissues had antagonistic effects on various GTD fungal pathogens related to Botryosphaeria, Eutypa, and Esca/Petri diseases48. Apart from the root growth promotion triggered by the Pseudomonas treatment and AMF, LEfSe analysis identified a higher abundance of Botrytis in the untreated root endosphere compared to the other treatments, suggesting an additional potential biocontrol property. Similarly, this result raises questions about the ability of bacteria to colonize plant roots, either by penetrating the root cortex as endophytes or by establishing themselves in the strict rhizosphere or on the root surface as epiphytes. Several PGPR acting as grapevine endophytes were explored for their growth promotion, such as Pseudomonas protegens MP1249,75, and Burkholderia phytofirmans PsJN50,51.

The processes governing the fate and persistence of biological inoculants in soil can be intricate, as they may result from the interplay of numerous variables, making them challenging to comprehend and predict52. Among the two species inoculated, only Pseudomonas brassicacearum was detected using MALDI-TOF MS in bacterized and mycorrhized-bacterized treatments after five months, but not in the other treatments. It has been proposed, using resistant mutants to antibiotics, that certain inoculants with PGP traits are able to persist in soils for up to seven weeks44. Moreover, using microsatellite markers, it has been shown that the biocontrol fungus Beauveria brongniartii was still present 14 years after application in fields, and even coexisted with indigenous strains53.

The combined addition of bacteria and AMF inoculum alters microbial community structure and functioning within the root system

Berg et al. (2021)54 reviewed the different effects of inoculants on indigenous plant microbiomes encompassing transient microbiome shifts, stabilization or increase of microbial diversity and evenness, restoration of a dysbiosis, targeted triggering of host beneficial microbes, and control of pathogens. In our case and based on amplicon sequencing results, we might have reduced the potential fungal pathogen Botrytis and functional pathotrophs (wood and undefined guild) while increasing potentially beneficial bacteria in the rhizosphere, such as Pseudomonas55, Rhizobium56, in the mycorrhized-bacterized treatment, and Candidatus Solibacter57, Phenylobacterium58, Gemmatimonas59, in the mycorrhized treatment. Cardinale et al. (2022)60 similarly reported enrichments of beneficial bacteria but non-hub taxa within root endosphere after inoculation of AMF on 1103P (Burkholderiaceae, Rhizobiaceae, Methylophilaceae, Bacillus, Massilia, and Streptomyces), which is consistent with our findings. As in other studies aiming to highlight the effects of mycorrhization by commercial AMF inoculants, it is important take into account the fact that these inoculants are, in most cases, not produced under axenic conditions and are probably accompanied by a range of diverse microorganisms, as well as compounds that may serve as nutrients for both the plant and the microbes. The bare-root plant itself (whether inoculated or not) also brings endophytic microorganisms, depending on the mother plants or the nursery, which can influence the responses observed. Bona et al. (2019)61 employed a metaproteome approach to investigate the rhizosphere of V. vinifera cv. Pinot Noir, and identified bacteria belonging to Streptomyces, Bacillus, Bradyrhizobium, Burkholderia, and Pseudomonas with highly active protein expression, primarily involved in P and N metabolism. These genera were also detected using MALDI-TOF MS within the rhizosphere of different conditions in this study. In the present study, differences were observed between mycorrhizal plants with or without the addition of the bacterial consortium, suggesting that the potential microbial community associated with the fungal inoculum is not responsible for the observed changes.

As with plants, introducing any microbial inoculant into the soil can be regarded as a disturbance to the native microbiota. These inoculation-induced changes in soil microbial composition can inherently alter soil functioning61. Functional redundancy, which is the presumption that several taxa provide the same ecological function within a microbial community62could explain the ecosystem’s resilience despite low microbial diversity and richness63. This hypothesis would justify the lower level of cultivable fungal and bacterial diversity observed in the rhizosphere of treated conditions compared to the untreated one, while having greater metabolic diversity measured using EcoPlates and PICRUSt2. The increased activity measured with EcoPlates was related to carbohydrates and carboxylic acid. Kohler et al. (2006)64 reported an increase in carbohydrates in the rhizosphere of lettuce plants inoculated with Pseudomonas mendocina and R. irregularis, which was presumed to be linked to soil stabilization. Moreover, R. irregularis is known to alter the carbohydrate content in the rhizosphere65. In a similar manner, R. irregularis is known to increase the levels of low-molecular-weight organic acids in the rhizosphere to mobilize P content bound to Fe oxides, which represents one of the key exchanges from the symbiont to the host in return for photosynthetic carbon67. The co-inoculation of F. mosseae and the growth-promoting rhizobacteria Ensifer meliloti on V. vinifera cv. Cabernet Sauvignon greatly increased the abundance of volatile organic compounds within roots68. As AMF do not acquire carbon from the soil due to their symbiotic relationship with the host, this could explain the lower carbohydrate metabolism inferred by PICRUSt2 within roots that were both mycorrhized and bacterized, compared to untreated roots.

Inoculation treatments synergistically complexify bacterial co-occurrence within root systems while having a limited impact on the fungal network

Co-occurrence networks offer a snapshot of the intricate relationships among microbial communities in various environments, including soil and plant-associated habitats69,70. These networks, associated with the functional stability of microbial communities, and characterized by their modularity, connectivity and other topological features, are constructed by identifying significant patterns of co-occurrence between microbial taxa, providing insights into potential interactions71. A higher degree of network complexity is thought to reflect a more robust and resilient community, which can serve as a proxy for assessing soil quality72, and plant health73. Previous studies have reported that microbial inoculation can lead to more complex and tightly connected microbial networks within plant-associated microbiomes, suggesting enhanced microbial interactions and functional integration. For instance, soybeans inoculated with Rhizobium resulted in an increased number of connections within the fungal community network74. Although this was not observed in the fungal network, an important shift in the microbiome was detected in this study. Similarly, inoculation of R. irregularis increased the bacterial network complexity within the root endosphere of maize75. Regarding vineyard soil, Torres et al. (2021)76 unveiled the increase of network complexity and stability due to AMF inoculation. In our study, a notable increase in the complexity of nodes and edges within the bacterial community network was observed in the root system treated with both AMF and bacteria, compared to untreated controls. Notably, this 559% increase in bacterial network edges substantially exceeded the sum of the effects of the individual treatments (64% increase with bacteria alone; 230% with AMF alone), providing clear quantitative evidence of a synergistic rather than merely additive interaction. This network-level synergy was accompanied by enhanced plant growth responses, with root biomass in co-inoculated plants surpassing the improvements observed with either treatment alone. The shifts observed in the microbial network are most likely linked to the change of microbial functionality and chemical compounds occurring within the root system. In co-occurrence networks, keystone taxa play a crucial role in community structure and function irrespective of their abundance76. Identifying a keystone species solely based on its topological role within the network is not sufficient unless its major ecological role within the ecosystem can be determined. Acidobacteriales being keystone taxa detected as a peripheral node in the co-inoculation condition has already been determined as such in soil fertility for rice78 and soil respiration79, and is primarily involved in carbon cycling and soil aggregation79. In addition, the combined mycorrhized and bacterized condition revealed the presence of Mesorhizobium, a keystone bacterial genus involved in soil nitrogen metabolism81, Blastocatellaceae, directly involved in the stability of soil microbial-mediated functions82, and even Onygenales, an important group of fungal decomposers in soil83. Based on detected keystone taxa, it is possible to obtain beneficial microbes for a synthetic community design by targeting specific species while avoiding large PGP screening83.

Conclusion

Multifunctional plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria were isolated from symptomatic and asymptomatic grapevines, with the most effective isolates originating from the rhizosphere of stressed grapevines. After growth induction in fast-growing L. sativum and 1103P plantlets in vitro, a selected bacterial treatment consisting of P. veronii and P. brassicacearum was inoculated on grapevines grown in a greenhouse, either singly or in combination with commercial AMF R. irregularis and F. mosseae. In addition to root biomass enhancement, the composition and functionality of the indigenous microbiome within the root system of treated conditions were altered, compared to untreated samples. Increased metabolic activity, such as carbohydrate metabolism, was accompanied by taxonomic shifts, including an enrichment of potentially beneficial bacteria and a reduction in fungal pathogens. Furthermore, the microbial community structure, as revealed by co-occurrence networks, increased in complexity upon treatment with microbial applications, unveiling keystone taxa within the microbial interactions. This work provides insights on the promising role of isolates from stressed environments that could alleviate microbiome dysbiosis linked to crop decline.

Data availability

Raw sequences have been deposited in Sequence Read Archive (NCBI), Bioproject PRJNA826314 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA826314.

References

Bernardo, S., Dinis, L. T., Machado, N. & Moutinho-Pereira, J. Grapevine abiotic stress assessment and search for sustainable adaptation strategies in Mediterranean-like climates. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 38, 66 (2018).

Azevedo-Nogueira, F. et al. The road to molecular identification and detection of fungal grapevine trunk diseases. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 1–18 (2022).

Sanmartin, C. et al. Restoration of an old vineyard by replanting of missing vines: effects on grape production and wine quality. Agrochimica 61, 154–163 (2017).

Vives-Peris, V., de Ollas, C., Gómez-Cadenas, A. & Pérez-Clemente, R. M. Root exudates: from plant to rhizosphere and beyond. Plant Cell Rep. 39, 3–17 (2020).

Leal, C., Trotel-Aziz, P., Gramaje, D., Armengol, J. & Fontaine, F. Exploring factors conditioning the expression of Botryosphaeria dieback in grapevine for integrated management of the disease. Phytopathology114, 21–34 (2024).

Aigoun-Mouhous, W. et al. Cadophora Sabaouae sp. Nov. And phaeoacremonium species associated with petri disease on grapevine propagation material And young grapevines in Algeria. Plant. Dis. 105, 3657–3668 (2021).

Gramaje, D. & Armengol, J. Fungal trunk pathogens in the grapevine propagation process: Potential inoculum sources, detection, identification, and management strategies. Plant Dis.95, 1040–1055 (2011).

Waite, H., Whitelaw-Weckert, M. & Torley, P. Grapevine propagation: Principles and methods for the production of high-quality grapevine planting material. New Z. J. Crop Hortic. Sci.43, 144–161 (2015).

Waite, H., May, P. & Bossinger, G. Variations in phytosanitary and other management practices in Australian grapevine nurseries. Phytopathol. Mediterr.52, 369–379 (2013).

Sayyed, R. Z. & Arora Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria for Sustainable Stress Managementvol. 12 (Springer Singapore, 2019).

Haidar, R., Amira, Y., Roudet, J., Marc, F. & Patrice, R. Application methods and modes of action of Pantoea agglomerans and Paenibacillus sp. to control the grapevine trunk disease-pathogen, Neofusicoccum parvum. OENO One 55, (2021).

Sabir, A., Yazici, M. A., Kara, Z. & Sahin, F. Growth and mineral acquisition response of grapevine rootstocks (Vitis spp.) to inoculation with different strains of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR). J. Sci. Food Agric.92, 2148–2153 (2012).

Funes Pinter, I. et al. Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria alleviate stress by AsIII in grapevine. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 267, 100–108 (2018).

Rolli, E. et al. Root-associated bacteria promote grapevine growth: from the laboratory to the field. Plant. Soil. 410, 369–382 (2017).

Marasco, R. et al. Plant growth promotion potential is equally represented in diverse grapevine root-associated bacterial communities from different biopedoclimatic environments. Biomed Res Int 1–17 (2013). (2013).

Marasco, R., Rolli, E., Fusi, M., Michoud, G. & Daffonchio, D. Grapevine rootstocks shape underground bacterial Microbiome and networking but not potential functionality. Microbiome 6, 3 (2018).

Chen, M., Arato, M., Borghi, L., Nouri, E. & Reinhardt, D. Beneficial services of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi – From ecology to application. Front. Plant Sci.9, 1–14 (2018).

Schreiner, R. P. Depth structures the community of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi amplified from grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) roots. Mycorrhiza30, 149–160 (2020).

Antolín, M. C. et al. Dissimilar responses of ancient grapevines recovered in Navarra (Spain) to arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis in terms of berry quality. Agronomy10, 473 (2020).

Noceto, P. A. A. et al. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, a key symbiosis in the development of quality traits in crop production, alone or combined with plant growth-promoting bacteria. Mycorrhiza31, 655–669 (2021).

Lowe, A., Rafferty-McArdle, S. M. & Cassells, A. C. Effects of AMF- and PGPR-root inoculation and a foliar Chitosan spray in single and combined treatments on powdery mildew disease in strawberry. Agricultural Food Sci. 21, 28–38 (2012).

Przybyłko, S., Kowalczyk, W. & Wrona, D. The effect of mycorrhizal fungi and PGPR on tree nutritional status and growth in organic apple production. Agronomy11, 1402 (2021).

O’Callaghan, M., Ballard, R. A. & Wright, D. Soil microbial inoculants for sustainable agriculture: Limitations and opportunities. Soil Use and Management vol. 38 1340–1369 Preprint at (2022). https://doi.org/10.1111/sum.12811

Kuang, L. et al. Diseased-induced multifaceted variations in community assembly and functions of plant-associated microbiomes. Front. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1141585 (2023).

Darriaut, R. et al. Microbial dysbiosis in roots and rhizosphere of grapevines experiencing decline is associated with active metabolic functions. Front. Plant Sci.15, 1358213 (2024).

Darriaut, R. et al. Soil composition and rootstock genotype drive the root associated microbial communities in young grapevines. Front. Microbiol. 13, 1031064 (2022).

Gordon, S. A. & Weber, R. P. Colorimetric estimation of indoleacteic acid. Plant. Physiol.26, 192–195 (1951).

Penrose, D. M. & Glick, B. R. Methods for isolating and characterizing ACC deaminase-containing plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Physiol. Plant.118, 10–15 (2003).

Cappuccino, J. C. & Sherman, N. Microbiology: A Laboratory Manual (Benjamin/Cumming, 1992).

Schwyn, B. & Neilands, J. B. B. Universal chemical assay for the detection and determination of siderophores. Anal. Biochem. 160, 47–56 (1987).

Pikovskaya, R. I. Mobilization of phosphorus in soil in connection with vital activity of some microbial species. Mikrobiologiya 17, 362–370 (1948).

Döbereiner, J. Isolation and identification of root associated diazotrophs. in Nitrogen Fixation with Non-Legumes 103–108 (Springer Netherlands, doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-0889-5_13. (1989).

Zott, K., Miot-Sertier, C., Claisse, O., Lonvaud-Funel, A. & Masneuf-Pomarede, I. Dynamics and diversity of non-Saccharomyces yeasts during the early stages in winemaking. Int. J. Food Microbiol.125, 197–203 (2008).

Martins, G. E. et al. Correlation between water activity (aw) and microbial epiphytic communities associated with grapes berries. OENO One. 54, 49–61 (2020).

Darriaut, R. et al. Grapevine decline is associated with difference in soil microbial composition and activity. OENO One55, 67–84 (2021).

Darriaut, R. et al. In grapevine decline, microbiomes are affected differently in symptomatic and asymptomatic soils. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 183, 104767 (2023).

Ozturk, S. & Aslim, B. Modification of exopolysaccharide composition and production by three cyanobacterial isolates under salt stress. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 17, 595–602 (2010).

Verma, E., Singh, S., Mishra, A. K. & Niveshika & Salinity-induced oxidative stress-mediated change in fatty acids composition of Cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. PCC7942. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 16, 875–886 (2019).

Khan, N. A., Khan, M. I. R., Ferrante, A. & Poor, P. Editorial: Ethylene: A key regulatory molecule in plants. Front. Plant Sci.8, 1–4 (2017).

Olanrewaju, O. S., Glick, B. R. & Babalola, O. O. Mechanisms of action of plant growth promoting bacteria. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol.33, 197 (2017).

Leontidou, K. et al. Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria isolated from halophytes and drought-tolerant plants: genomic characterisation and exploration of phyto-beneficial traits. Sci. Rep. 10, 14857 (2020).

de Souza, R., Meyer, J., Schoenfeld, R., da Costa, P. B. & Passaglia, L. M. P. Characterization of plant growth-promoting bacteria associated with rice cropped in iron-stressed soils. Ann. Microbiol. 65, 951–964 (2015).

Darriaut, R. et al. Grapevine rootstock and soil Microbiome interactions: keys for a resilient viticulture. Hortic. Res. 9, uhac019 (2022).

Finkel, O. M., Castrillo, G., Herrera Paredes, S., Salas González, I. & Dangl, J. L. Understanding and exploiting plant beneficial microbes. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol.38, 155–163 (2017).

Chu, T. N., Van Bui, L. & Hoang, M. T. T. Pseudomonas PS01 isolated from maize rhizosphere alters root system architecture and promotes plant growth. Microorganisms 8, (2020).

Cervantes-Vázquez, T. J. Morphophysiological, enzymatic, and elemental activity in greenhouse tomato saladette seedlings from the effect of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Agronomy 11, 1–15 (2021).

Jindo, K. et al. Application of biostimulant products and biological control agents in sustainable viticulture: A review. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 1–28 (2022).

Niem, J. M., Billones-Baaijens, R., Stodart, B. & Savocchia, S. Diversity profiling of grapevine microbial endosphere and antagonistic potential of endophytic Pseudomonas against grapevine trunk diseases. Front. Microbiol.11, 1–19 (2020).

Andreolli, M. et al. In vivo endophytic, rhizospheric and epiphytic colonization of vitis vinifera by the plant-growth promoting and antifungal strain pseudomonas protegens MP12. Microorganisms 9, 1–14 (2021).

Compant, S. et al. Endophytic colonization of Vitis vinifera L. by Burkholderia phytofirmans strain psjn: from the rhizosphere to inflorescence tissues. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 63, 84–93 (2008).

Trong, N. H. et al. Biological control of grapevine crown gall disease, caused by Allorhizobium vitis, using Paraburkholderia phytofirmans PsJN. PhytoFrontiers™2, 391–403 (2022).

Manfredini, A. et al. Current methods, common practices, and perspectives in tracking and monitoring bioinoculants in soil. 12, 1–22 (2021).

Enkerli, J., Widmer, F. & Keller, S. Long-term field persistence of Beauveria brongniartii strains applied as biocontrol agents against European cockchafer larvae in Switzerland. Biol. Control29, 115–123 (2004).

Berg, G., Kusstatscher, P., Abdelfattah, A., Cernava, T. & Smalla, K. Microbiome modulation—Toward a better understanding of plant microbiome response to microbial inoculants. Front. Microbiol.12, 1–12 (2021).

Erdogan, U. et al. Effects of root plant growth promoting rhizobacteria inoculations on the growth and nutrient content of grapevine. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal.49, 1731–1738 (2018).

Andreolli, M., Lampis, S., Zapparoli, G., Angelini, E. & Vallini, G. Diversity of bacterial endophytes in 3 and 15 year-old grapevines of Vitis vinifera cv. Corvina and their potential for plant growth promotion and phytopathogen control. Microbiol. Res. 183, 42–52 (2016).

Wei, D. et al. Pseudomonas chlororaphis IRHB3 assemblies beneficial microbes and activates JA-mediated resistance to promote nutrient utilization and inhibit pathogen attack. Front. Microbiol. 15, 1–15 (2024).

Jiang, Z. et al. Impacts of red mud on lignin depolymerization and humic substance formation mediated by laccase-producing bacterial community during composting. J. Hazard. Mater. 410, 124557 (2021).

Liu, C. et al. Soil bacterial communities of three types of plants from ecological restoration areas and plant-growth promotional benefits of Microbacterium invictum (strain X-18). Front. Microbiol. 13, 1–8 (2022).

Cardinale, M. et al. Vineyard establishment under exacerbated summer stress: effects of mycorrhization on rootstock agronomical parameters, leaf element composition and root-associated bacterial microbiota. Plant. Soil. 478, 613–634 (2022).

Bona, E. et al. Metaproteomic characterization of Vitis vinifera rhizosphere. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 95, fiy204 (2018).

Mawarda, P. C., Le Roux, X., van Dirk, J. & Salles, J. F. Deliberate introduction of invisible invaders: A critical appraisal of the impact of microbial inoculants on soil microbial communities. Soil Biol. Biochem. 148, 107874 (2020).

Louca, S. et al. Function and functional redundancy in microbial systems. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2, 936–943 (2018).

Biggs, C. R. et al. Does functional redundancy affect ecological stability and resilience? A review and meta-analysis. Ecospherehttps://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.3184 (2020).

Kohler, J., Caravaca, F., Carrasco, L. & Roldán, A. Contribution of Pseudomonas mendocina and Glomus intraradices to aggregate stabilization and promotion of biological fertility in rhizosphere soil of lettuce plants under field conditions. Soil Use Manag.22, 298–304 (2006).

Mechri, B. et al. Changes in microbial communities and carbohydrate profiles induced by the mycorrhizal fungus (Glomus intraradices) in rhizosphere of Olive trees (Olea Europaea L). Appl. Soil. Ecol. 75, 124–133 (2014).

Andrino, A. et al. Production of organic acids by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and their contribution in the mobilization of phosphorus bound to iron oxides. Front. Plant Sci. 12, 1–13 (2021).

Velásquez, A. et al. Responses of Vitis vinifera cv. Cabernet sauvignon roots to the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus Funneliformis mosseae and the plant growth-promoting rhizobacterium Ensifer meliloti include changes in volatile organic compounds. Mycorrhiza30, 161–170 (2020).

Aschenbrenner, I. A., Cernava, T., Erlacher, A., Berg, G. & Grube, M. Differential sharing and distinct co-occurrence networks among spatially close bacterial microbiota of bark, mosses and lichens. Mol. Ecol.26, 2826–2838 (2017).

Hou, M. et al. Pedogenesis of typical zonal soil drives belowground bacterial communities of arable land in the Northeast China plain. Sci. Rep. 13, 14555 (2023).

Gao, C. et al. Co-occurrence networks reveal more complexity than community composition in resistance and resilience of microbial communities. Nat. Commun. 13, 1–12 (2022).

de Vries, F. T. et al. Soil bacterial networks are less stable under drought than fungal networks. Nat. Commun.https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-05516-7 (2018).

Qiao, Y. et al. Core species impact plant health by enhancing soil microbial Cooperation and network complexity during community coalescence. Soil Biol. Biochem. 188, 109231 (2024).

Xu, H. et al. Rhizobium inoculation drives the shifting of rhizosphere fungal community in a host genotype dependent manner. Front. Microbiol. 10, 1–14 (2020).

Huang, T. et al. The colonization of the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus Rhizophagus irregularis affects the diversity and network structure of root endophytic bacteria in maize. Sci. Hort. 326, 112774 (2024).

Torres, N., Yu, R. & Kurtural, S. K. Inoculation with mycorrhizal fungi and irrigation management shape the bacterial and fungal communities and networks in vineyard soils. Microorganisms9, 1273 (2021).

Banerjee, S., Schlaeppi, K. & van der Heijden, M. G. A. Keystone taxa as drivers of Microbiome structure and functioning. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 16, 567–576 (2018).

Wang, J. L. et al. Balanced fertilization over four decades has sustained soil microbial communities and improved soil fertility and rice productivity in red paddy soil. Sci. Total Environ. 793, 148664 (2021).

Zhu, K., Jia, W., Mei, Y., Wu, S. & Huang, P. Shift from flooding to drying enhances the respiration of soil aggregates by changing microbial community composition and keystone taxa. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1–15 (2023).

Kalam, S. et al. Recent Understanding of soil acidobacteria and their ecological significance: a critical review. Frontiers Microbiology 11, (2020).

Xun, W. et al. Specialized metabolic functions of keystone taxa sustain soil microbiome stability. Microbiome9, 1–15 (2021).

Luo, J. et al. Organic fertilization drives shifts in Microbiome complexity and keystone taxa increase the resistance of microbial mediated functions to biodiversity loss. Biol. Fertil. Soils. 59, 441–458 (2023).

Coleine, C., Selbmann, L., Guirado, E., Singh, B. K. & Delgado-Baquerizo, M. Humidity and low pH boost occurrence of Onygenales fungi in soil at global scale. Soil Biol. Biochem.167, 108617 (2022).

Zheng, Y. et al. Exploring biocontrol agents from microbial keystone taxa associated to suppressive soil: a new attempt for a biocontrol strategy. Frontiers Plant. Science 12, (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by FranceAgrimer/CNIV and funded as part of the “Plan National Dépérissement du Vignoble” program of the Vitirhizobiome project (grant number FAM no. 22001206). The authors would like to thank the vineyard owners for their permission to sample the soil used as matrix for the greenhouse experiment. The authors also thank the Genotoul bioinformatics platform Toulouse Midi-Pyrenees and Sigenae group for providing storage resources via Galaxy instance. The authors thank Marc Meynadier for his help in the choice of the bioinformatics pipelines.

Funding

This work was supported by FranceAgrimer/CNIV funded as part of the program ‘Plan National Dépérissement du Vignoble’ within the project Vitirhizobiome (grant number 2018–52537).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RD, VLau, IM-P, and NO conceived the study. RD and JW performed the enzymatic assays and the in vitro bioassays with Lepidum and grapevine. RD managed the greenhouse experiment. RD, GM, PB, IM-P, NO, and VLai contributed to the sampling, the data collection and analysis. RD and VLai performed DNA extraction and metabarcoding analyses. RD and JT did the bioinformatic analysis. RD prepared the figures and tables. RD and VLau wrote the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Darriaut, R., Lailheugue, V., Wastin, J. et al. Rhizobacteria from vineyard and commercial arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi induce synergistic microbiome shifts within grapevine root systems. Sci Rep 15, 27884 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12673-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12673-5