Abstract

Bone mineral density (BMD) is an important indicator of bone health, and a decrease in BMD is closely associated with an increased risk of osteoporosis (OP) and fractures. Although BMD decline is typically age-related, the issue of decreased bone density is becoming increasingly prominent in younger populations. Chronic inflammation is considered one of the key factors contributing to decreased bone density. The neutrophil percentage to albumin ratio (NPAR), as an inflammatory marker, has gained attention in recent years for its role in various diseases. However, research on its relationship with bone density remains limited. This study aims to explore the association between NPAR and decreased bone density, and to provide potential biomarkers for early screening of OP. Finally, Mendelian randomization (MR) was employed to assess the independent causal effects of neutrophil percentage and albumin levels on OP. This study is based on data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) conducted between 2011 and 2018, including 10,961 eligible adults. BMD was assessed using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA), and NPAR was calculated based on neutrophil percentage and serum albumin levels. The non-linear relationship between NPAR and BMD was analyzed using restricted cubic splines (RCS), and multivariable linear regression and logistic regression models were used to assess their association. Additionally, gender-stratified analyses were performed, and subgroup and threshold analyses were conducted to explore the relationship between NPAR and OP in different genders. MR revealed that elevated neutrophil percentage significantly increased the risk of OP, whereas higher albumin levels were associated with a reduced OP risk. Restricted cubic spline analysis revealed a negative association between NPAR and BMD, with a significant non-linear inflection point occurring at approximately NPAR = 1.0. Further multivariable regression analysis showed that, in the unadjusted model, NPAR was negatively associated with BMD. However, after adjusting for demographic factors, the relationship reversed, showing a marginally significant positive association. After full adjustment, the association between NPAR and BMD was no longer significant, suggesting that demographic and lifestyle factors play an important confounding role in the relationship between NPAR and bone density. Additionally, gender-stratified analysis using multivariable regression indicated that the association between NPAR and low BMD/OP was more significant in men, whereas no statistical significance was found in women. Subgroup analysis suggested that hypertension, obesity, and older age might exacerbate the impact of NPAR on OP. Threshold analysis found that in women, NPAR ≥ 1.49 was significantly associated with OP risk (OR = 2.89, P = 0.016), while no clear threshold effect was observed in men. This study found a complex relationship between NPAR and bone mineral density, with the association being influenced by various demographic and lifestyle factors. In men, NPAR may be associated with low BMD/OP through inflammatory responses, while in women, this association is more influenced by additional covariates. As a composite inflammatory-nutritional biomarker, NPAR may hold potential for osteoporosis screening and risk prediction, but further research is needed to validate its clinical application value.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

BMD is one of the important indicators for assessing bone strength1.A decrease in BMD leads to fragile bones, increasing the risk of fractures, which has a profound impact on individual health and quality of life, and places a heavy burden on global public health systems2.Low bone mineral density is becoming an important health issue affecting people of all age groups globally. Studies have shown that OP causes more than 8.9 million fractures annually worldwide, with the decrease in bone mineral density being one of the core characteristics of OP3.Although BMD decline is typically associated with older adults, the issue of decreased BMD is becoming increasingly prominent in younger populations due to changes in lifestyle and dietary habits. The increased fracture risk it causes severely threatens the quality of life of patients, especially in the elderly. Osteoporotic fractures not only result in a significant medical burden but may also lead to long-term disability or even death4.Therefore, early screening and intervention are essential strategies for preventing BMD decline and its complications. Through early screening, the harmful effects of BMD decline can be effectively prevented and managed, helping to maintain a healthy lifestyle. In recent years, with the rapid development of medical imaging technologies, DXA has become the gold standard for assessing BMD and diagnosing OP5.However, DXA still has several significant limitations, including radiation exposure, high equipment costs, and being unsuitable for pregnant women and certain special populations6,7,8.Therefore, exploring safer, more convenient, and accessible methods for assessing bone mineral density can not only enrich our diagnosis but also contribute to continuous health management.

Numerous studies have shown that the decline in bone mineral density and the occurrence of OP are closely associated with chronic inflammation9,10.Inflammatory factors (such as IL-6 and TNF-α) promote osteoclastogenesis and inhibit osteoblast activity, leading to increased bone resorption and decreased bone formation11,12.Additionally, inflammation exacerbates bone loss by affecting intercellular interactions within the bone microenvironment. Therefore, inflammatory biomarkers may have significant value in the diagnosis and prognosis assessment of OP.

In recent years, blood inflammatory parameters have gradually become important indicators for disease assessment due to their cost-effectiveness and easy accessibility13.Among them, NPAR, as a novel inflammatory marker, has attracted considerable attention for its role in inflammation-related diseases14.Specifically, it integrates two key inflammatory-nutritional pathological pathways14.Neutrophils, as key mediators of systemic inflammation, activate various signaling pathways to secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines, while albumin, synthesized by the liver, is inversely related to the inflammatory state. During inflammation, the liver produces less albumin, and the consumption of albumin increases15.Albumin further regulates the inflammatory response by binding to pro-inflammatory substances and promoting neutrophil degranulation16.Studies have shown that NPAR is closely associated with various inflammation-related diseases, such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and cancer17,18,19. However, research on the relationship between NPAR and bone loss or OP is relatively limited.

As an economical and easily accessible blood inflammatory parameter, NPAR may have significant clinical value in the assessment of bone loss or OP. Our study should further explore its application in disease screening, progression monitoring, and prognosis assessment, with the aim of providing new insights for the diagnosis and treatment of bone loss and OP.

Materials and methods

Study population

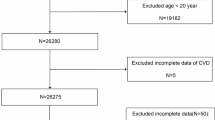

All participant information was derived from NHANES, which aims to assess the nutrition and health status of the general U.S. population based on a cross-sectional design. NHANES is part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and is updated every two years. The screening process is shown in Fig. 1. We extracted data from NHANES for the years 2011–2018 (2011–2012, 2013–2014, 2015–2016, and 2017–2018), resulting in a total of 39,156 participants after data merging. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) age ≥ 20 years and (ii) participants with complete data on BMD, neutrophil percentage (per 100 cells/µL), and serum albumin levels (mmol/L). Participants without serum albumin data (n = 14,466) were excluded. Participants without neutrophil percentage data (n = 73) and participants without BMD data (n = 9,774) were also excluded. After these exclusions, 14,843 participants remained. Further exclusion of participants under the age of 20 (n = 3,882) resulted in a final sample size of 10,961 participants. All participants in this study provided informed consent, and the study was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of the National Center for Health Statistics.

BMD testing and definition of low BMD/OP

All participants (included in the final analysis) underwent BMD testing via DXA, conducted by certified radiologic technicians using the Hologic QDR-4500 A fan-beam densitometer (Hologic; Bedford, MA, USA). All DXA test data were analyzed using Hologic APEX software (version 4.0). Additional details are available on the NHANES website. Furthermore, participants were divided into two groups based on hip BMD: normal bone mass group and low BMD/OP group. The definitions of bone loss and OP were based on the average BMD of 20-29-year-old male or female populations as the reference value. Individuals with a BMD score lower than 1 standard deviation or more below the normal value were considered to have bone loss or OP, while individuals with BMD values higher than 1.0 standard deviation above the normal value were considered to have normal BMD20,21.

Definition of NPAR

In this study, NPAR was derived from the standardized complete blood count measurements performed on NHANES participants using the Beckman Coulter DxH 800 analyzer at the mobile examination centers. NPAR was calculated by dividing the neutrophil percentage (per 100 cells/µL) by the serum albumin level (mmol/L)22.This composite index reflects both the intensity of inflammation activation (through neutrophil percentage) and the body’s nutritional-inflammatory status (through albumin levels). Compared to any single biomarker, it may provide better predictive value for inflammation-related pathology. The use of NHANES data, with standardized laboratory protocols, ensures strict quality control, enhancing the reliability of our measurements. Notably, NPAR is our primary exposure variable. Therefore, we performed a normality test on the results of NPAR, which exhibited characteristics of normal distribution. The results are shown in Fig. 2-A. Additionally, as shown in Fig. 2-B, we used density curves to compare the data against theoretical percentiles, illustrating the degree of deviation from normal distribution.

Covariates

Our analysis included several covariates of interest, including demographic characteristics (age, gender, race/ethnicity), socioeconomic factors (education level, marital status, poverty-to-income ratio), lifestyle behaviors (smoking, alcohol consumption), medical history (diabetes, hypertension), and dietary components (intake of calcium and vitamin D supplements). Age was categorized into young (20–35 years), middle-aged (36–50 years), and elderly (≥ 50 years) groups. Gender was categorized into two groups (male and female). Racial/ethnic groups included non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and Hispanic/other. Comorbidities were defined based on established NHANES criteria for diabetes and hypertension. The intake of calcium and vitamin D supplements was recorded (yes/no). Socioeconomic stratification included education level (less than high school/high school or some college/college or higher) and income-to-poverty ratio (< 1.3/1.3–3.5/>3.5). Lifestyle factors included alcohol consumption (none/1–3 drinks per day/≥4 drinks per day), smoking status (current/occasional/never), and physical activity level (< 500/500–1000/≥1000 met-minutes). Body mass index (BMI) classifications followed standard categories (underweight/normal weight: <25; overweight: 25–30; obese: ≥30).

Mendelian randomization

To investigate the potential causal relationship between NPAR and OP risk, we conducted a two-sample MR analysis using neutrophil percentage and albumin levels as proxy exposures, given the unavailability of direct genome-wide association study (GWAS) data for NPAR as a derived variable. Summary statistics were obtained from the IEU Open GWAS project (https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/datasets/), including neutrophil percentage (ukb-d-30200_irnt), albumin levels (ebi-a-GCST90013990), and osteoporosis (finn-b-M13_OSTEOPOROSIS). We employed three complementary MR approaches - inverse-variance weighted (IVW) as the primary method, weighted median (WM), and MR-Egger regression - to estimate causal effects, with all analyses performed using the TwoSampleMR package in R. Instrumental variables were selected based on genome-wide significance thresholds (P < 5 × 10 − 8 or P < 5 × 10 − 6) and underwent linkage disequilibrium clumping (R2 < 0.001 within a 10,000 kb window) to ensure robustness, with results expressed as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using R software (version 4.3.1). For missing data, multiple imputation (m = 5) was applied for continuous variables, and missing categorical variables were treated as separate categories. Results are presented as odds ratios (ORs) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and related statistical metrics. Baseline characteristics were summarized as means ± standard deviations for continuous variables and frequencies (percentages) for categorical variables. Nonlinear relationships between NPAR and BMD were examined using RCS. Multivariable linear and logistic regression models were constructed using a three-step adjustment strategy: Model 1 (raw associations), Model 2 (adjusted for demographic factors: gender, age, and race), and Model 3 (fully adjusted for clinical, socioeconomic, and lifestyle covariates). Gender-specific associations were investigated through gender stratified analysis, and subgroup analysis was conducted using forest plots to explore heterogeneous effects across metabolic and demographic strata. Additionally, a threshold effect of NPAR on low BMD /OP was further examined using threshold analysis of NPAR. We performed all MR analyses using the “TwoSampleMR” R package (version 0.6.1).A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

To characterize the baseline features of the study population, our analysis included 10,961 participants with comprehensive baseline characteristics, as shown in Table 1. The cohort exhibited a balanced gender distribution (50.87% male, 49.13% female) and age stratification (40.28% young adults [20–35 years], 37.56% middle-aged adults [36–50 years], 22.16% older adults [> 50 years]). The racial composition included 34.66% non-Hispanic white, 21.65% non-Hispanic black, and 43.69% Hispanic/other participants. The average BMD was 1.25, and NPAR was 1.34. The prevalence of diabetes was 7.46%, and hypertension was 23.98%. Participants were classified into two groups based on BMD scores: 83.34% had normal BMD, while 16.66% had low BMD/OP.Regarding supplementation, 32.72% of participants took calcium supplements, and 30.50% took vitamin D supplements. Socioeconomic characteristics included education level (18.33% < high school, 21.82% high school/partially completed college, 59.85% ≥ college), and income distribution (32.79% low [< 1.3], 36.37% moderate [1.3–3.5], 30.85% high [> 3.5]). Lifestyle factors recorded alcohol consumption (26.58% non-drinkers, 43.04% moderate drinkers [1–3 drinks/day], 30.38% heavy drinkers [≥ 4 drinks/day]), smoking status (39.33% current smokers, 11.98% occasional smokers, 48.69% non-smokers), and physical activity levels (95.04% highly active).Body composition analysis showed that 30.62% had normal weight (BMI < 25 kg/m²), 31.14% were overweight (BMI 25–30 kg/m²), and 38.24% were obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m²). Physical activity levels, based on MET-minutes, revealed 0.05% had low activity, 4.92% had moderate activity, and 95.04% were highly active23.

RCS analysis

RCS analysis revealed different patterns of the NPAR-BMD relationship across various models. In the unadjusted analysis (Fig. 3-A), a significant linear negative correlation was observed (β range: -0.06 to 0.00). At NPAR levels between 0.5 and 2.5, the β coefficient decreased monotonically, reaching its peak at NPAR ≈ 1.5 (β ≈ -0.06).After multivariable adjustment, the correlation remained significant (p-value all = 0.002), but a clear nonlinear relationship emerged (p-nonlinear = 0.002) (Fig. 3-B). This nonlinear pattern was characterized by a sharp decline from NPAR ≈ 0.5-1.0 (with a peak β ≈ -0.07), followed by a weakening at higher levels. The transition from a linear to a nonlinear pattern suggests a potential modification of the effect by covariates. The abrupt threshold effect around NPAR = 1.0 suggests possible biological saturation or competing pathways.The continued significance in the adjusted model confirmed the independent association between NPAR and BMD, while the nonlinear dynamics highlighted the importance of modeling the threshold effect in fully adjusted analyses. Specifically, the adjusted model identified a turning point at NPAR ≈ 1.5, where each unit increase below this threshold was associated with a 0.07-unit decrease in BMD (95% CI: -0.09 to -0.05), while above this threshold, the decrease was only 0.04 units (95% CI: -0.06 to -0.02).

Multivariable regression analysis

We further performed multivariable regression analysis to examine the dynamic relationship between NPAR and BMD across different adjustment models. Table 2 presents the results of multivariable regression analysis testing the relationship between NPAR and BMD through progressive adjustment models.In the crude model (Model 1), a significant negative correlation was observed between NPAR and BMD (β = -0.03, 95% CI: -0.04 to -0.02, P < 0.001), indicating that each one-unit increase in NPAR was associated with a 0.03-unit decrease in BMD. After adjusting for demographic variables, including gender, age, and race (Model 2), the direction of the relationship reversed, showing a marginally significant positive correlation (β = 0.01, 95% CI: 0.01 to 0.03, P = 0.041). This reversal suggests that these demographic factors introduced substantial confounding effects, with the protective effect of younger age potentially counteracting the negative association observed in the crude analysis.In the fully adjusted model (Model 3), which included clinical factors (OP status, calcium and vitamin D supplementation), socioeconomic status, lifestyle factors (alcohol consumption, smoking), and metabolic parameters (BMI, physical activity), the correlation between NPAR and BMD became nonsignificant (β = -0.00, 95% CI: -0.01 to 0.01, P = 0.384). This pattern suggests that the initially observed association between high NPAR levels and low BMD may primarily be attributed to confounding by demographic characteristics, lifestyle factors, and metabolic parameters, rather than representing an independent biological relationship.The complete attenuation of the effect after comprehensive adjustment of clinical, socioeconomic, and behavioral covariates indicates that the predictive value of NPAR for bone health is largely mediated through these interrelated pathways. These findings underscore the complexity of interpreting NPAR and highlight the importance of rigorous multivariable adjustments in OP research to differentiate true biological associations from confounding effects.Therefore, to better clarify these associations, we performed a gender-stratified analysis to explore potential sex-specific differences in the relationship between NPAR and low BMD/OP.

Male and female population baseline characteristics

To better elucidate these associations, we conducted sex-stratified analyses to explore potential gender-specific differences in the relationship between NPAR and low BMD/OP.

The baseline characteristics for 5,576 male participants are shown in Table 3. Among them, 4,771 (85.56%) had normal bone mass (OP group 0), and 805 (14.44%) had low BMD/OP (OP group 1), as shown in Fig. 4-A. There was a significant difference in NPAR between the case group (OP group 1) and the control group (OP group 0) (P < 0.05). Additionally, significant differences were observed in age, race, education level, income level, alcohol intake, diabetes, hypertension, and BMI (P < 0.05), suggesting these factors may be associated with the risk of OP group. However, no significant associations were found between calcium intake, vitamin D intake, smoking status, and physical activity metabolism with OP group (P > 0.05), indicating these factors have a weaker impact on the male OP group.

The baseline characteristics for 5,385 female participants are shown in Table 4. Among them, 4,364 (81.04%) had normal bone mass (OP group 0), and 1,021 (18.96%) had low BMD/OP (OP group 1), as shown in Fig. 4-B. Significant differences were observed across multiple demographic and clinical variables (P < 0.05): age distribution (χ²=277.00), racial composition (χ²=86.12), calcium supplementation (χ²=5.48), vitamin D supplementation (χ²=8.03), education level (χ²=6.92), income-poverty ratio (χ²=7.35), quality of life indicators (χ²=13.63), and BMI categories (χ²=222.25). The OP group showed notable characteristics, including: (1) older age (42.70% aged ≥ 60 years, compared to 18.38% in the control group), (2) a higher proportion of white participants (55.04% vs. 41.18%), (3) greater nutritional supplementation (calcium: 39.08% vs. 35.17%), (4) lower socioeconomic status, and (5) a conflicting BMI distribution, with both normal weight (51.71% vs. 27.54%) and obesity (30.56% vs. 44.39%) categories showing high prevalence. Notably, no significant differences were found in inflammatory markers (NPAR: 1.37 ± 0.26 vs. 1.39 ± 0.24, P = 0.053), metabolic comorbidities (diabetes: P = 0.927; hypertension: P = 0.687), or lifestyle factors (smoking: P = 0.508; physical activity: P = 0.134). These findings suggest that while socioeconomic and anthropometric factors are strongly correlated with OP status, traditional inflammatory markers and certain behavioral factors may not be reliable discriminators for this population. The observed patterns highlight the complex, multifactorial nature of OP pathogenesis, particularly the unexpected nutritional supplementation findings, which may reflect treatment effects or detection biases in high-risk populations.

Multivariable regression analysis for males and females

To further investigate the sex-specific differences in the association between NPAR and low BMD/OP, we performed logistic regression analyses.

Table 5 presents the results of a multivariable logistic regression analysis for males, showing a dynamic relationship between NPAR and the likelihood of OP. In the unadjusted model (Model 1), NPAR exhibited a significant positive correlation (OR = 1.52, 95% CI: 1.10–2.08, P = 0.010). However, after adjusting for basic demographic factors (age and race) in Model 2, this association weakened and became non-significant (OR = 1.23, 95% CI: 0.88–1.72, P = 0.219). Notably, in the fully adjusted model (Model 3), which included clinical factors (diabetes, hypertension), nutritional status (calcium/vitamin D supplementation), socioeconomic factors, lifestyle behaviors, and metabolic parameters, the association regained statistical significance (OR = 1.48, 95% CI: 1.94–2.10, P = 0.030).

Table 6 presents the results of a multivariable logistic regression analysis for females, showing a dynamic relationship between NPAR and the progressively adjusted models. In the unadjusted model (Model 1), NPAR exhibited a moderate protective association (OR = 0.75, 95% CI: 0.56–0.99, P = 0.041). This protective trend persisted but became non-significant after adjusting for demographic factors (Model 2: OR = 0.79, 95% CI: 0.58–1.06, P = 0.112). Notably, in the fully adjusted model (Model 3), which included clinical comorbidities, nutritional factors, socioeconomic status, lifestyle behaviors, and metabolic parameters, the association reversed and became non-significant (OR = 1.10, 95% CI: 0.81–1.50, P = 0.544).

Subgroup analysis and forest plot

To further validate the association between NPAR and low BMD/OP in key subgroups, we conducted stratified analyses by sex (male and female separately).

As shown in Fig. 5, the multivariable analysis of 5,576 male participants reveals significant associations between various risk factors and clinical outcomes. The overall model indicates a moderate but statistically significant positive correlation (OR = 1.52, 95% CI: 1.10–2.08, P = 0.010). Notably, several subgroups show particularly strong associations: hypertensive patients (OR = 3.02, 95% CI: 1.59–5.72, P < 0.001), obese individuals (BMI group 3: OR = 9.66, 95% CI: 4.77–19.56, P < 0.001), and heavy drinkers (ALQ group 4: OR = 2.45, 95% CI: 1.44–4.15, P < 0.001) exhibit the highest risk. Demographic factors, including older age (≥ 60 years: OR = 2.13, P = 0.009) and race group 1 (OR = 2.36, P = 0.004), are also significantly associated with outcomes. In contrast, calcium (OR = 2.65, P = 0.001) and vitamin D supplementation (OR = 1.59, P = 0.014) show positive correlations, which may indicate confounding due to indication bias. Significant interactions are observed for hypertension (Pinteraction = 0.021), BMI (Pinteraction < 0.001), and calcium intake (Pinteraction = 0.028), suggesting that the effect varies across different populations. These findings highlight the complex interplay of metabolic, demographic, and lifestyle factors in influencing clinical outcomes, particularly the strong impact of cardiovascular risk factors and body composition measurements. The results emphasize the need for personalized risk assessment approaches that consider these multidimensional determinants.

As shown in Fig. 6, the multivariable logistic regression analysis of 5,385 female participants reveals significant heterogeneity in the association of risk factors across different subgroups. The analysis highlights significant correlations between various risk factors and OP risk. The overall model shows a significant positive correlation (OR = 1.52, 95% CI: 1.10–2.08, P = 0.010). Notably, hypertension exhibits the strongest association (OR = 3.02, 95% CI: 1.59–5.72, P < 0.001), followed by smoking (OR = 1.95, 95% CI: 1.20–3.17, P = 0.007) and older age (≥ 60 years: OR = 2.13, 95% CI: 1.21–3.75, P = 0.009). Metabolic factors, including higher BMI (OR = 1.60, 95% CI: 1.30–1.96, P < 0.001) and reduced physical activity (OR = 1.59, 95% CI: 1.15–2.19, P = 0.005), are significantly associated with increased OP risk. In contrast, calcium (OR = 2.65, 95% CI: 1.47–4.80, P = 0.001) and vitamin D supplementation (OR = 1.59, 95% CI: 1.10–2.31, P = 0.014) show a positive correlation with OP, which may indicate reverse causality or confounding by indication. Racial differences are notable, with race group 1 showing particularly high risk (OR = 2.36, 95% CI: 1.31–4.27).

Threshold analysis

To further explore the impact of NPAR on low BMD/OP, we conducted threshold analysis using the segmented package in this study.

Table 7 shows the potential nonlinear relationship between NPAR and OP.group in males. The analysis results indicate that no significant threshold effect was found, suggesting that the relationship between NPAR and OP.group may be linear. There appears to be a positive correlation between NPAR and OP.group (standard linear model P = 0.030). No significant threshold (inflection point) was detected, indicating that the relationship is more likely to be linear rather than piecewise nonlinear (P = 0.878). The OR at NPAR ≥ 0.92 remains at the borderline significant level (P = 0.050), but the overall analysis does not support the existence of a threshold effect.

Table 8 shows the potential nonlinear relationship between NPAR and OP.group in females. The analysis results indicate a significant threshold effect between NPAR and OP.group (P for likelihood test = 0.004), suggesting that the impact of NPAR on OP.group may vary depending on the NPAR level. There is a threshold effect between NPAR and OP.group in females (P for likelihood test = 0.004). When NPAR < 1.49, there is no significant association between NPAR and OP.group (P = 0.120). However, when NPAR ≥ 1.49, NPAR shows a significant positive association with OP.group (OR = 2.89, P = 0.016), indicating that higher NPAR levels may increase the risk of OP.group. Standard linear regression did not show a significant association (P = 0.544), but the two-segment linear regression model suggests that high NPAR levels may be associated with an increased incidence of OP.group.

Mendelian randomization analysis

To further investigate the potential causal relationship between NPAR and OP risk, we conducted a two-sample MR analysis using the IVW method as our primary approach, which provides the most reliable estimates when all SNPs are valid instrumental variables24. As shown in Fig. 7, elevated neutrophil percentage was significantly associated with increased osteoporosis risk (IVW OR = 1.189, 95% CI: 1.015–1.393, p = 0.032; Fig. 7A-B), while higher albumin levels demonstrated a protective effect against osteoporosis (IVW OR = 0.803, 95% CI: 0.667–0.967, p = 0.021; Fig. 7C-D). Supplementary methods (MR-Egger and weighted median) showed slightly lower statistical significance (p > 0.05)25,26.

Mendelian randomization analysis of neutrophil percentage and albumin levels in relation to OP: (A–B) Genetic association between neutrophil percentage and osteoporosis, and effect estimates using the IVW method. (C–D) Genetic association between albumin levels and osteoporosis, and effect estimates using the IVW method. NSNP, OR, 95% CI, and p-value are shown.

Discuss

In recent years, researchers have identified several novel biomarkers that show great potential in OP patients. One study suggests that combining plasma/serum biomarkers such as bone-specific alkaline phosphatase, the RANKL/OPG ratio, and tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase with diagnostic algorithms can aid in the early diagnosis and subtype classification of OP27,28.Despite their promising prospects, the widespread implementation of these novel biomarkers in routine clinical practice remains limited due to challenges related to accessibility and availability. Increasing evidence suggests that chronic low-grade inflammation plays a key role in the development and progression of OP29,30,31. Studies have demonstrated a potential association between inflammatory biomarkers, such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), and BMD32,33,34,35. However, their clinical utility remains limited. Although CRP is a sensitive marker of systemic inflammation, its lack of specificity hinders the differentiation between various types of inflammation, such as infectious and metabolism-related inflammation32. Moreover, its association with BMD improvement is not significant in individuals with low BMI36. NLR, while convenient and easily accessible, is susceptible to confounding factors, including glycemic variability in patients with diabetes and other metabolic comorbidities33,37. Additionally, its calculation does not include nutritional parameters, limiting its capacity to reflect the interplay between inflammation and nutritional status37,38. As a result, the widespread implementation of these novel biomarkers in routine clinical practice remains challenging.OP is primarily attributed to an imbalance in bone metabolism, characterized by increased osteoclast activity, decreased osteoblast function, and the identification of inflammatory factors such as IL-6 and TNF-α as key mediators in the onset and persistence of OP39,40,41.Studies have shown that nutrition and dietary habits can regulate the metabolic processes and inflammatory responses involved in OP. Therefore, given the key roles of inflammation and nutrition in OP, identifying new biomarkers based on these factors is crucial for assessing disease risk in clinical settings and guiding targeted interventions42.

As a composite biomarker, NPAReffectively reflects the body’s inflammatory state and nutritional status by combining the percentage of neutrophils and albumin levels43.In recent years, NPAR has been shown to have significant value in predicting various diseases, including acute kidney injury, septic shock, and colorectal cancer44,45,46.However, the relationship between NPAR and low BMD/OP has not been fully explored.

NPAR may have a potential association with the development and progression of OP by comprehensively reflecting inflammation and nutritional status. In bone metabolism, both inflammatory factors and nutritional levels jointly affect the dynamic balance of bone remodeling. Chronic low-grade inflammation is a significant influencing factor in OP. Inflammatory markers such as IL-6 and TNF-α can promote the activation of osteoclasts while inhibiting osteoblast differentiation, leading to increased bone resorption and decreased bone formation, which in turn results in reduced bone density and disruption of bone microstructure47,48.Studies have found that the incidence of OP is significantly higher in patients with chronic inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, compared to the general population, indicating that the inflammatory state may play a key role in the imbalance of bone metabolism49.In addition, nutritional status is equally crucial for bone health, with albumin levels serving as an important indicator of the body’s nutritional state. Studies have shown that low albumin levels are closely associated with an increased risk of OP and may raise the incidence of fractures50.Insufficient protein intake can affect bone matrix synthesis, while calcium and vitamin D, as core nutrients for bone metabolism, play a crucial role in bone health. Their deficiency can impair bone mineralization, leading to accelerated bone density loss51.Therefore, malnutrition may impact bone health through multiple pathways, exacerbating the progression of OP.NPAR, as a novel indicator, combines two key factors—inflammation (neutrophil percentage) and nutrition (albumin levels)—providing a comprehensive biomarker for assessing the risk of OP52,53.When NPAR increases, it may indicate a state of chronic inflammation coupled with malnutrition, which could further exacerbate bone metabolism imbalance and increase the risk of OP. Therefore, NPAR could become a powerful tool for predicting OP and provide a reference for early intervention.

This study systematically evaluated the association between NPAR and low BMD/OP in a large-scale population sample.

The main findings can be summarized in three points: First, the relationship between NPAR and BMD showed significant gender differences and a threshold effect. Second, this association is complexly regulated by demographic characteristics, metabolic factors, and lifestyle factors. Finally, the predictive value of NPAR for OP risk remains independent in males, whereas it is only evident at high NPAR levels (≥ 1.49) in females. These findings provide new epidemiological evidence for understanding the role of inflammation-nutrition balance in bone metabolism.

The discovery of gender-specific associations is particularly noteworthy. Therefore, we conducted logistic regression, subgroup analysis, and threshold analysis by gender, based on several considerations: First, the sexual dimorphism in bone metabolism is well-recognized, with male and female bone mineral density being influenced by different hormones and physiological mechanisms54.Secondly, our preliminary analysis indicates that the significant confounding effect observed after adjusting for demographic factors suggests that gender may alter the effect. Thirdly, numerous studies have also reported that gender-specific differences in inflammatory markers and nutritional status may have different impacts on bone health55,56,57,58,59.he positive association between NPAR and the risk of OP in men (OR = 1.48) remained significant after full adjustment, suggesting that NPAR may influence bone metabolism through pathways independent of traditional risk factors. For example, pro-inflammatory cytokines released by neutrophils (such as IL-6 and TNF-α) can directly activate osteoclasts60.The nonlinear threshold effect observed in women (OR = 2.89 when NPAR ≥ 1.49) may be related to an enhanced inflammatory response under conditions of estrogen deficiency61. Notably, the higher rate of calcium/vitamin D supplementation in the female OP group was accompanied by poorer bone health status (OR = 2.65). This seemingly paradoxical phenomenon may reflect a ‘treatment paradox’—that is, individuals at higher risk are more likely to receive supplementation, rather than indicating any harmful effect of the supplements themselves62.

From a pathophysiological perspective, NPAR, as a composite marker reflecting both inflammation (neutrophil percentage) and nutritional status (albumin), may exhibit a threshold effect corresponding to a critical point of ‘inflammation-nutrition imbalance.’ When NPAR exceeds 1.49, the reduced antioxidant capacity caused by hypoalbuminemia may synergize with neutrophil-mediated oxidative stress, thereby accelerating bone resorption62.This hypothesis is supported by our RCS analysis, which identified an inflection point in the effect around NPAR ≈ 1.5, consistent with the systemic inflammation threshold proposed in previous studies63.Additionally, subgroup analysis revealed an interaction between obesity (BMI ≥ 30) and NPAR, suggesting that adipose tissue-derived inflammatory factors may have an amplifying effect on the association between NPAR and bone health. Furthermore, our MR analysis revealed independent causal effects of neutrophil percentage and albumin levels on osteoporosis risk: elevated neutrophil percentage significantly increased osteoporosis risk, whereas higher albumin levels conferred protection. Given that neutrophil percentage reflects systemic inflammatory status and albumin represents nutritional reserves, the proposed NPAR may serve as a composite biomarker that more comprehensively captures the pathophysiological imbalance underlying osteoporosis development.

This study has several limitations: its cross-sectional design precludes causal inference, NPAR was measured without accounting for dynamic changes, and other inflammatory markers were not evaluated for comparison. Additionally, the current conclusions are based on independent analyses of NPAR components rather than direct genetic instrumental variables for NPAR itself. However, its strengths lie in the large, representative sample and rigorous multivariable adjustments. The clinical implications are as follows: (1) NPAR ≥ 1.49 may serve as a low-cost early warning indicator for OP screening; (2) routine assessment of inflammatory status should be included in OP management; and (3) future interventional studies should explore the benefits of anti-inflammatory strategies in populations with NPAR above specific thresholds. These findings call for the integration of inflammation-nutrition balance into OP risk assessment frameworks and offer potential targets for precision prevention.

Summary

NPAR may be a valuable and convenient inflammation-nutrition marker for predicting decreased BMD or the risk of OP. However, given the inherent limitations of this study, further large-scale research is needed to investigate the role of NPAR in OP more comprehensively.

Data availability

Data availability statement: Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/default.aspx.

References

Viral, N. S. Bone mineral density as a surrogate biomarker for fracture risk reduction. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 8(11), 875–876 (2020).

Cauley, J. A. et al. New challenges: Use and interpretation of radius bone mineral density. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 110(1), e1–e7 (2024).

Johnston, C. B. & Dagar, M. Osteoporosis in older adults. Med. Clin. N. Am. 104(5), 873–884 (2020).

Hiroyuki, S. et al. Impact of osteosarcopenia on disability and mortality among Japanese older adults. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 14(2), 1107–1116 (2023).

Paul Henry, G. Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) to measure bone mineral density (BMD) for diagnosis of osteoporosis - experimental data from artificial vertebrae confirms significant dependence on bone size. Bone Rep. 17, 101607 (2022).

Marissa, K. & Langaker, M. D. Dual energy X-ray absorptiometry. StatPearls 20, 291 (2021).

Alawi, M. et al. Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scan versus computed tomography for bone density assessment. Cureus.13(2), e13261 (2021).

Astrit, M. G. et al. Osteoporosis during Pregnancy. Case Report and Review 29(2), (2021).

Travis, F. et al. Chronic inflammation associated with obesity exacerbates bone loss in mice. J. Immunol. 202(1), 182–189 (2019).

Sinead, N. D. et al. An association between abnormal bone turnover, systemic inflammation, and osteoporosis in patients with chronic pancreatitis: A case-matched study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 110(2), 336–345 (2015).

Birte, K. et al. The cytokine interleukin-11 crucially links bone formation, remodeling and resorption. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 60, 18–27 (2021).

Hiroki, Y. et al. THU0079 Anti-IL-6 receptor antibody suppresses systemic bone loss by not only normalizing bone resorption but also enhancing bone formation in a mouse model of collagen-induced arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 72, A190 (2013).

Omar Al, T. A. et al. The predictive value of hematological markers in renal cell carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 63(6), 577–589 (2023).

Lina, W. et al. The association between neutrophil percentage-to-albumin ratio (NPAR) and depression among US adults: A cross-sectional study. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 21880 (2024).

Frank, W. et al. Interleukin-6 signaling in liver-parenchymal cells suppresses hepatic inflammation and improves systemic insulin action. Cell Metab. 12(3), 237–249 (2010).

Irina, V. G. et al. Hypohalous acid-modified human serum albumin induces neutrophil NADPH oxidase activation, degranulation, and shape change. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 68, 326–334 (2014).

Li, X., Gu, Z. & Gao, J. Elevated neutrophil percentage-to-albumin ratio predicts increased all-cause and cardiovascular mortality among individuals with diabetes. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 27870 (2024).

Ko, C. A., et al. Prognostic Value of Neutrophil Percentage-to-Albumin Ratio in Patients with Oral Cavity Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 14(19), 4892 (2022).

Zhao, M. et al. Predictive value of the neutrophil percentage-to-albumin ratio for coronary atherosclerosis severity in patients with CKD. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 24(1), 277 (2024).

Watson, S. L. et al. High-intensity resistance and impact training improves bone mineral density and physical function in postmenopausal women with osteopenia and osteoporosis: The LIFTMOR randomized controlled trial. J. Bone Miner. Res. 33(2), 211–220 (2018).

Wang, K. et al. Associations of healthy eating index-2015 with osteoporosis and low bone mass density in postmenopausal women: A population-based study from NHANES 2007–2018. Front. Nutr. 11, 1388647 (2024).

Liu, C.F. and L.W. Chien, Predictive Role of Neutrophil-Percentage-to-Albumin Ratio (NPAR) in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Advanced Liver Fibrosis in Nondiabetic US Adults: Evidence from NHANES 2017–2018. Nutrients, 2023. 15(8).

Piercy, K. L. et al. The physical activity guidelines for americans. JAMA 320(19), 2020–2028 (2018).

Debbie, A. L. et al. Mendelian randomization: Using genes as instruments for making causal inferences in epidemiology. Stat. Med. 27(8), 1133–1163 (2008).

Jack, B. et al. Consistent estimation in Mendelian randomization with some invalid instruments using a weighted median estimator. Genet. Epidemiol. 40(4), 304–314 (2016).

Jack, B., George Davey, S. & Stephen, B. Mendelian randomization with invalid instruments: Effect estimation and bias detection through Egger regression. Int. J. Epidemiol. 44(2), 512–525 (2015).

Anne, K. H. et al. Machine learning and radiomics identify novel biomarkers of bone loss. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 30, S81–S82 (2022).

Fahimeh, M. et al. Factors associated with trabecular bone score and bone mineral density; A machine learning approach. J. Clin. Densitom. 25(4), 518–527 (2022).

Hiroshi, T. SP0147 effects of systemic inflammation on osteoblasts, osteoclasts, and osteocytes. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 74(S2), 36 (2015).

Jasminka, Z. I. et al. Low-grade chronic inflammation perpetuated by modern diet as a promoter of obesity and osteoporosis. Arh. Hig. Rada Toksikol. 65(2), 139–148 (2014).

Patrice, F. et al. Bone loss, osteoporosis, and fractures in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A review. J. Clin. Med. 9(10), 3361 (2020).

Agnieszka, R. et al. P536 Is there any association between fat body mass and bone mineral density in patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease?. J. Crohn’s Colitis 17(S1), i664–i665466 (2023).

Cuma, M. & Murat, G. Neutrophil-Lymphocyte ratio and Platelet-Lymphocyte ratio as useful predictive markers of prediabetes and diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 11, S127 (2017).

Demir Cendek, B. et al. The role of inflammatory and nutritional indices in postmenopausal osteoporosis: A retrospective study. J. Clin. Med. 13(24), 7741 (2024).

Somayyeh, S. et al. Predictive value of serum inflammatory biomarkers in postmenopausal osteoporosis: A cross-sectional study in Northwest Iran. Heliyon. 10(17), e36247 (2024).

Khadijeh, M. et al. Metabolically healthy/unhealthy components may modify bone mineral density in obese people. Arch. Osteoporos. 12(1), 95 (2017).

Xiang, L. et al. Non-diabetic elderly populations: the MHR as a protective factor against bone abnormalities. Front. Endocrinol. 15, 1408467 (2024).

René, R., Emmanuel, B. & Tara, C. B. S. Nutritional intake and bone health. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 9(9), 606–621 (2021).

Junjie, L. et al. Regulating type H vessel formation and bone metabolism via bone-targeting oral micro/nano-hydrogel microspheres to prevent bone loss. Adv. Sci. 10(15), e2207381(2023).

He, H. et al. Muscle-derived extracellular vesicles improve disuse-induced osteoporosis by rebalancing bone formation and bone resorption. Acta Biomater. 157, 609–624 (2023).

Martina, B. et al. IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α only in combination influence the osteoporotic phenotype in Crohn’s patients via bone formation and bone resorption. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 27(1), 45–56 (2018).

Xiaohua, L. et al. The effects of different dietary patterns on bone health. Nutrients 16(14), 2289 (2024).

Mousa, N. et al. Neutrophil percentage-to-albumin ratio is a new diagnostic marker for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: A prospective multicenter study. Gut Pathog. 16(1), 18 (2024).

He, H. M. et al. Association between neutrophil percentage-to-albumin ratio and contrast-associated acute kidney injury in patients without chronic kidney disease undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. J. Cardiol. 79(2), 257–264 (2022).

Gong, Y. et al. Increased neutrophil percentage-to-albumin ratio is associated with all-cause mortality in patients with severe sepsis or septic shock. Epidemiol. Infect. 148, e87 (2020).

Liao, Y. C. et al. Combined fibrinogen-to-pre-albumin ratio and carbohydrate antigen 19–9 score is a promising metric to predict progression of metastatic colorectal mucinous adenocarcinoma. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 35(5), e23757 (2021).

Nicole Lynn, E. & Frédérique, F. Evaluation of Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha (TNF-α) in Sleep-Deprived Menopausal-Induced Rats and the Impact on Bone Health. FASEB J. 34(S1), 1 (2020).

Xuanru, L. et al. Interleukin-32 Induce Production of IL-6 in Multiple Myeloma Bone Marrow Stromal Cells. Blood 128(22), 3253 (2016).

Dghaies, A. et al. AB1223 what about bone mineral density in rheumatoid arthritis patients using glucocorticoids?. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 82, 1839 (2023).

Bruno Miguel, F. et al. AB0608 bone mineral density, vitamin D status and bone metabolism in a cohort of adult patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 80, 1339 (2021).

Mir, S.-A. et al. Influence of vitamin D levels on bone mineral density and osteoporosis. Ann. Saudi Med. 31(6), 602–608 (2011).

Sahar, G. et al. Significance of serum albumin and derived neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio score in assessment of disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Egypt. Rheumatol. Rehabil. 47, 5 (2020).

Ülkem Şen, U. & Murat, D. The relationship between neutrophil lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet lymphocyte ratio (PLR), hemoglobin albumin lymphocyte and platelet (HALP) score and bone mineral density in Hemodialysis Patients. J. Orthop. Res. Rehabil. 2(1), 5–8 (2024).

Kung, A. W. C. Sex hormones and bone mineral density in men and women. Bone 43(1), S24 (2008).

Shuai, C. et al. Association between inflammatory markers and bone mineral density: a cross-sectional study from NHANES 2007–2010. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 18(1), 305 (2023).

Alicja, E. G. & Monika, M.-M. Influence of age and sex on bone mineral density in dialysis patients. Adv. Perit. Dial. 23:77-81(2007).

Elisa, A. M. et al. Response of bone mineral density, inflammatory cytokines, and biochemical bone markers to a 32-week combined loading exercise programme in older men and women. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 57(2), 226–233 (2013).

Zhiqiang, Y. et al. Different associations between waist circumference and bone mineral density stratified by gender, age, and body mass index. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 23(1), 786 (2022).

Tzyy-Ling, C., Chun-Hung, L. & Yuh-Feng, W. Effects of vegetarian diet on bone mineral density. Tzu Chi Med. J. 33(2), 128–134 (2021).

Yiming, Z. et al. Effect of TNF-α and IL-6 on compact bone-derived cells. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 18(3), 441–451 (2021).

Vered, S. & Kala, V. Optimizing vitamin D concentrations for breast cancer risk reduction. Medicine 92(3), 132–134 (2013).

Force, U. S. P. S. T. et al. Vitamin D, calcium, or combined supplementation for the primary prevention of fractures in community-dwelling adults. JAMA 319(15), 1600–1612 (2018).

Wang, Y. et al. Association of systemic immune biomarkers with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: A cross-sectional study of NHANES 2007–2018. Front. Nutr. 11, 1415484 (2024).

Funding

This research was supported by the Construction Plan for Specialized Disease and Specialty Peak Projects (Document No. 99 of Southwest Medical University Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine (2024)).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Tao Liu and Xianghan Hou and Zhijiang Fu and Zongchao Liu wrote the main manuscript text, Yingjin Luo and Xuanang Jiang and Ke Gaod and Jiale Lvb prepared Figs. 4, 5 and 6 , Liquan Wang and Yang Zhou prepared Figs. 4, 5 and 6, All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The studies involving humans were approved by the NCHS Research Ethics Review Board (ERB). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, T., Hou, X., Luo, Y. et al. To explore the association between the neutrophil percentage to albumin ratio and low bone mineral density/osteoporosis based on NHANES 2011–2018. Sci Rep 15, 29544 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12732-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12732-x