Abstract

Poor solubility of drugs represents a major obstacle against drug delivery, so pharmaceutical industry is exploring the use of nanocrystals as a promising approach to enhance the bioavailability of those medications with improving their pharmacokinetics. This study aims to improve etoricoxib properties via nanocrystal form using an acid-base precipitation method. This method is simple, environment- friendly, and prefers non-organic solvents and chemicals, thus overcoming challenges in developing dosage forms. Prepared nanocrystals were optimized for several factors such as stabilizer type and concentration, amount of drug, time and speed of homogenization. FT-IR, DSC, X-ray diffraction, and TEM characterizations were conducted on the optimized nanocrystal formula. The findings showed a successful inclusion of etoricoxib as nanocrystals with a mean particle size of 210.30 ± 10.20 nm, PDI of 0.277 ± 0.01, and a zeta potential of − 74.10 ± 0.61 mV. TEM imaging revealed well-defined cubic-shaped nanoparticles, indicating morphological uniformity and excipient compatibility. Solubility studies demonstrated notable enhancement in the aqueous solubility of etoricoxib nanocrystals (137.75 ± 1.34 µg/mL) compared to the pure drug (87.70 ± 1.41 µg/mL). Additionally, the nanocrystals exhibited rapid dissolution profile, achieving 91.49 ± 0.01% drug release within 5 min. These results suggest that using nanocrystals to improve the aqueous solubility and dissolution of medications with poor solubility is a potential strategy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Solubility is a key factor in the effectiveness of curative dosage forms1. It significantly influences a drug’s oral absorption, bioavailability, and overall pharmacokinetic behavior. Generally, higher solubility leads to better dissolution and enhanced absorption2. According to the Biopharmaceutical Classification System (BCS), Class II drugs are characterized by poor aqueous solubility, which presents significant challenges in terms of oral absorption and bioavailability3. Various methods had been taken into consideration to improve the solubilization and dissolution of those medications, including micronization, solid dispersion and complexation4. Drug micronization; a size reduction in which fewer than 10 microns of particle size is produced, but it is not recommended since the product’s tendency to clump together reduces its effective surface area for dissolving5,6. Solid dispersion technique, despite its positive impact in improving drug solubility and dissolution, is very limited for commercial use due to several drawbacks such as costly and time-consuming preparation methods, challenges integrating it into dosage formulation, and problems with scaling up the manufacturing process7,8. As for complexation; the creation of complexes between the medication and a ligand via Intermolecular associations (covalent or non-covalent bonds), yet this method has drawbacks, e.g. the chemical must be able to form complexes with ligands9. For compounds with very limited solubility, solubility enhancement may be quite modest. This also applies to solubilization by combination processes, such as complexation with pH adjustment. Lastly, the presence of a ligand can lead to problems with quality control, regulations, and potential toxicity, which can make the development process more difficult and costly10. Another crucial method is nanosization, which improves drug solubility by increasing surface area and particle wettability via particle size reduction into nanoscale11. The process of nanosization involves creating drug nanoparticles (nanocrystals) or nano-carriers (lipid and polymeric nano-systems)12,13. Nanocrystals (NCs), pure active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) with a size range of 10–1000 nm, have gained attention in pharmaceutical innovation in recent decades, especially for improving the bioavailability of drugs that are poorly soluble14. NCs are simple and economical formulating procedures that primarily rely on the active ingredients themselves with the subtle addition of small amounts of polymers or surfactants for stabilization properties; adsorbing at the NPs’ surface and preventing the drug particles from aggregating, so NCs overcome problems associated with the counteracting other approaches15,16. Compared to other nano-systems, nanocrystals offer several benefits, such as the ability to achieve maximum drug loading. As a result, a lower dosage is taken into consideration, improving bioavailability and therapeutic efficacy with lowering adverse effects. Also, NCs require a low quantity of surfactants for stabilization so reduce the related toxicity and provide more safety profiles15,17. NCs can be prepared using various methods, including top-down techniques such as high-pressure homogenization and milling. In these approaches, the starting material consists of larger solid particles, which are reduced to the nanoscale through mechanical force. A key advantage of these methods is the avoidance of organic solvents18. However, high-pressure homogenization has certain limitations: it requires thermostable components, involves high process temperatures and energy input, demands complex equipment, and may lead to thermal or mechanical degradation of the drug, potentially resulting in reduced yield19. Similarly, the milling technique is associated with drawbacks such as metal contamination from the milling media, prolonged processing times, high energy consumption, and reduced crystallinity due to mechanical stress20. In contrast, the acid–base precipitation method relies on the pH-dependent solubility of hydrophobic drugs, where the drug is first dissolved in an acidic or basic medium and then precipitated by neutralization. This approach is simple, cost-effective, rapid, and does not require complex equipment or the use of organic solvents, making it a more environmentally friendly alternative. Given these advantages, the acid–base precipitation method was selected in this study for NC preparation, with a focus on critical formulation and process optimization21. Etoricoxib (ETX), 5-chloro- 6′-methyl- 3[4-(methyl sulfonyl) phenyl] − 2, 3′–bypyridine, is a highly potent and selective cyclooxygenage-2 (COX-II) inhibitor compared to celecoxib and rofecoxib, ETX is administered orally as an analgesic and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug22,23. Compared to COX-1 inhibitors, ETX has substantially fewer upper gastrointestinal issues and is used to treat rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, postoperative tooth pain, chronic back pain, and acute gout24. It is categorized as a low-solubility chemical since ETX is a class II, weakly basic compound (pKa of 4.6) with reduced solubility in the pH 4–7 range25. Improving the solubility of ETX helps to improve its dissolving behavior, which in turn improves its pharmacokinetics and therapeutic efficacy26. Numerous studies have attempted to improve ETX solubility through various techniques, which subsequently increased its bioavailability27,28,29. This study aimed to investigate the efficacy of nanocrystals made using the safest and simplest method in enhancing the dissolution behavior of etoricoxib.

Materials and methodology

Materials

Etoricoxib (EX) was a kind gift from APEX PHARMA, Cairo, Egypt, poloxamer407 (F127) and mannitol were purchased from sigma-Aldrish. St. Louis, MO, USA and LANXESS Co., Cologne, Germany respectively, soyabean lecithin was obtained from alpha chemika Co., Cairo, Egypt. All other chemicals were of analytical grade and utilized as received.

Methodology

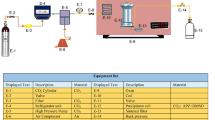

Preparation of ETX-NCs

ETX-NCs were prepared using acid-base precipitation method30. In this process, a specific amount of ETX was dissolved in a 0.5 M HCl solution, while a stabilizer was dissolved in a solution of NaOH with certain molar concentration, both solutions were formed under magnetic stirring. The acidic solution was then slowly added to the alkaline solution under homogenization at a controlled speed and for a set duration. Freeze drying of formed nanosuspension was conducted to form nanocrystals in powder form using mannitol (5% w/v) as a cryoprotectant.

Optimization of NCs

Screening of stabilizer type, pH of the medium and stabilizer concentration

Various stabilizers were tested while keeping other parameters constant to determine the most effective one for ensuring the stability of the prepared ETX-NCs. The evaluation was based on particle size, PDI, and zeta potential measurements. Once the most suitable stabilizer was identified, the pH of the medium and stabilizer’s concentration were adjusted accordingly. Table 1 shows the composition of ETX-NCs formulae.

Optimization of ETX-NCs using Box–Behnken design

The type and concentration of the selected stabilizers were kept constant based on the results of preliminary optimization (Table 1). To optimize other formulating conditions of NCs, a Box–Behnken design with 3 factors and 3 levels was employed, focusing on the amount of ETX (mg), homogenization speed (rpm), and homogenization time (min), using Design Expert, version13 software. The Box–Behnken design was chosen for its efficiency in saving time and cost by minimizing the number of runs required for optimization. A total of 17 runs were performed, including 5 replicated center points, where each run evaluated for particle size, PDI, and zeta potential. The independent variables considered were the amount of ETX (A), homogenization speed (B), and homogenization time (C), while the dependent variables were particle size (Y1), PDI (Y2), and zeta potential (Y3). The levels of independent and dependent variables are shown in Table 2.

Characterization of prepared NCs

Particle size, PDI and zeta potential

The Malvern Zetasizer Nano Series, utilizing dynamic light scattering (DLS) technology31was employed to measure particle size, PDI, and zeta potential of the prepared formulations. Prior to analysis, the formulations were diluted 100-fold with distilled water to ensure accurate readings.

Drug content

A specified weight of NCs (equivalent to 340.9 µg) was dissolved in a 10 mL volumetric flask containing a mixture of phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) and methanol in a 9:1 ratio. The NCs were initially dissolved in 1 mL of methanol, followed by vortexing for 5 min. Then, 9 mL of phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) was added under continuous vortexing. The drug content of ETX was measured using UV spectrophotometer at λ max of 235 nm against blank (similarly treated) after suitable dilutions. Drug content was detected using the following equation32:

Electron microscopy analysis

Samples (raw ETX and ETX-NCs) were examined for morphology using transmission electron microscopy and scanning electron microscopy. For TEM analysis, 5 µL of the prepared NCs suspension was placed onto a carbon-coated copper grid, allowing the NCs to settle for 3–5 min. After settling, the excess fluid was removed by blotting with absorbent paper. The grid was then negatively stained with 2% uranyl acetate for 3–5 min. Finally, digital images of the NCs were captured using a Gatan axis-mount 2k x 2k digital camera. While for SEM determination, the monolayer of each sample was mounted on a metallic stub and coated with a thin 10 nm layer of gold using the sputter coating technique. The samples were then examined under the SEM at an accelerating voltage of 15 keV33.

Fourier infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR)

The infrared spectra of intact ETX, Lecithin, Mannitol, the selected ETX-NCs formulation, physical mixture of NCs components (ETX, lecithin, mannitol) and the physical mixture of ETX-NCs without mannitol (ETX, lecithin) were recorded using FT-IR spectrophotometer (Shimadzu IR-345, Japan) to investigate any potential interactions between ETX and the excipients used in the NCs formulation. Each sample was individually grounded with potassium bromide and compressed into disks. Spectral scanning was conducted in the range of 500 to 4000 cm−134.

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) was employed to assess the physical state of ETX and evaluate potential drug-excipient interactions within the NCs. The DSC analyses were conducted on samples of ETX, lecithin, mannitol, ETX-NCs formula, physical mixtures of the NCs components (ETX, lecithin, and mannitol), and physical mixture without mannitol (ETX, lecithin) using a computer-interfaced Shimadzu calorimeter. Approximately 5 mg of each sample were precisely weighed, sealed in an aluminum pan, and heated at a rate of 10 °C/min across a temperature range of 25–300 °C35.

Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD)

Samples of ETX, lecithin, mannitol, a physical mixture of ETX, lecithin, and mannitol, a physical mixture of ETX and lecithin, and the optimized NCs formula were analyzed using X-ray diffractometer (Philips PW 1710) using Cu Kα radiation (tube operated at 40 kV, 100 mA). Data were collected over an angular range from 4 to 60° 2θ in continuous scan mode, with a step size of 0.06° 2θ and a time counting of 60 s per step36.

Saturation solubility

To evaluate the impact of formulating ETX as NCs on its saturation solubility, samples of pure ETX, a physical mixture (ETX, lecithin, and mannitol) in the same ratios as in the NCs, and the optimized NCs preparation were added in excess to vials containing 10 mL of phosphate buffer solution (pH 7.4). The vials were shaken at 100 rpm under thermostatic conditions of 37 ± 0.5 °C for 72 h. The samples were then filtered using a 0.45 μm syringe filter, diluted, and analyzed using UV spectrophotometer at λ max of 235 nm against a similarly processed blank37.

In-vitro drug dissolution

The paddle type dissolution apparatus (USP apparatus 2, Electrolab, TDT-06 N, India), was employed to study the dissolution of ETX and its nanocrystal form. Samples of pure ETX, a physical mixture (ETX, lecithin, and mannitol), physical mixture (ETX and lecithin), physical mixture of ETX and mannitol and the selected ETX-NCs, each equivalent to 8 mg of ETX, were added to 350 mL of phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) maintained at 37 ± 0.5 °C for 4 h. The paddles were set to rotate at 75 rpm. At specified time intervals (5, 10, 20, 60, 120, and 240 min), 5 mL aliquots were withdrawn and were replaced with fresh dissolution medium to maintain sink conditions. The withdrawn samples were filtered using a 0.45 μm syringe filter and analyzed by UV spectrophotometry at λ max of 235 nm against a similarly prepared blank38.

Statistical analysis

Both the Newman-Keuls post-hoc test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used to determine the significance between the various groups (* (P < 0.05), **(P < 0.01), ***(P < 0.001), and NS (non-significant). Each experiment was carried out in triplicate, and the mean ± SD was used to display the data.

Results and discussion

Preparation and optimization of ETX-NCs

The acid-base precipitation method was effectively employed to prepare ETX-NCs. Investigating the stabilizing impact of several stabilizer types throughout the ETX-NCs preparation, lecithin was found to be the most appropriate one achieving NCs (F5) with tiny PS (226.65 ± 1.20 nm, p value < 0.001), low PDI (0.349 ± 0.00, p value < 0.001) and maximum ZP (-78.50 ± 0.63 mV, P value < 0.001) in comparison to other tested stabilizers (Fig. 1a). Lecithin’s substantial stabilizing impact is mostly attributed to the steric barrier that its bulky structure creates around the nanoparticles. Consequently, repulsive forces are in effect. Also, the stabilizing effect may be aided by the amphiphilic character of lecithin, which permits the hydrophobic interaction between the hydrophobic lecithin tail and the ETX hydrophobic areas39,40,41. The ETX-NCs formulated with Tween 80 and PVP exhibited a reduced size (114.50 ± 7.77 and 138.80 ± 8.06, p value < 0.01) compared to those prepared with lecithin (Fig. 1a). However, their PDI was notably higher (0.99 ± 0.01 and 0.559 ± 0.01, p value < 0.001) indicating a decrease in stability (-20.25 ± 0.64 and − 13.15 ± 1.20, p value < 0.001) respectively. While for formulations prepared with Pluronic F68, higher PS and lower zeta potential were obtained (375.25 ± 5.16 and − 22.1 ± 0.57, p value < 0.001) with minimum PDI (0.304 ± 0.01, p value < 0.001) compared to that prepared with lecithin (Fig. 1a). Considering the pH of prepared ETX-NCs, three distinct pH levels were investigated (5.5, 7.4, and 8.5) to obtain the best conditions for preparation. The results cited in Fig. 1b, illustrate the effect of lowering pH in enhancing NCs characters; NCs prepared at pH 5.5 achieved significantly lower particle size (PS) and polydispersity index (PDI) values of 204.45 ± 2.19 (p < 0.01) and 0.277 ± 0.00 (p < 0.01), respectively, compared to those prepared at higher pH levels (7.4 and 8.5). This effect can be attributed to the influence of pH changes on the nucleation and growth dynamics of the system. At pH 5.5, the system likely undergoes supersaturation more rapidly, promoting homogeneous nucleation, which leads to the formation of smaller and more uniform nanoparticles. In contrast, as the pH increases, the rate of precipitation slows, and heterogeneous nucleation becomes more prominent, resulting in larger and less uniform particles42,43,44. Furthermore, etoricoxib is a weak base (pKa ≈ 4.6) with pH-dependent solubility, showing increased solubility at alkaline pH. At higher pH values, the delayed onset of nucleation due to increased solubility allows for faster particle growth once nucleation begins, which contributes to the formation of larger particles with a broader size distribution, compared to its behavior at pH 5.525,45. Considering zeta potential, it was found that raising the pH (7.4 and 8.5) achieved more negative values (-79.50 ± 0.35 and − 78.50 ± 0.63) than that observed at pH 5.5 (-74.50 ± 0.28), (Fig. 1b) which may relate to more ionization of phosphate group of lecithin at higher pH39,40. As a conclusion, stable ETX-NCs were obtained at the different examined pH conditions. Based on those results, pH 5.5 was selected for further evaluations. By changing lecithin concentration (0.025,0.05,0.1,0.15,0.2 and 0.4%w/v), it was found that 0.1%w/v was the optimum concentration, Fig. 1c, with small PS of 204.45 ± 2.19, low PDI of 0.277 ± 0.00 and high zeta potential of -74.50 ± 0.28. Also, it was shown that smaller concentrations of lecithin (0.025% and 0.05% w/v) resulted in larger PS and PDI (453.85 ± 3.18 nm, 0.417 ± 0.01 and 359.60 ± 1.83 nm, 0.408 ± 0.02, p value < 0.001) respectively. However higher concentrations (0.15%, 0.2% and 0.4%) resulted in slight increase in PS and PDI (212.35 ± 2.62 nm, 0.364 ± 0.01, 205.30 ± 0.71 nm, 0.296 ± 0.01 and 207.00 ± 1.41 nm, 0.314 ± 0.03), Fig. 1c. Based on these results, the best formula for further optimization was found to be F5 (0.1% w/v of lecithin, 30 mg ETX, homogenized at 21000 rpm for5 minutes, pH 5.5), since it has the lowest surfactant content, resulting in the lowest PS, monodispersity index, and highest stabilization of the generated NCs.

a Effect of different stabilizer types on particle size, PDI and zeta potential, one way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis; *** (P < 0.001), **(P < 0.01). b Effect of pH of the medium for NCs formulation on particle size, PDI and zeta potential, one way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis; ** (P < 0.01). c Effect of different concentrations of lecithin on particle size, PDI and zeta potential, one way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis; *** (P < 0.001), ** (P < 0.01), *(P < 0.05).

Optimization of ETX-NCs by Box–Behnken design

Table 3 displays the makeup and outcomes of the impact of independent variables on the responses under study. F5 was recommended by the software. Numerical optimization based on the desirability function approach resulted in an overall desirability score of 0.777, reflecting an acceptable compromise among the targeted formulation goals namely, the minimization of particle size and polydispersity range (0.252,0.290), and the maximization of zeta potential. The optimal formulation conditions yielded minimum size with low PDI and maximum zeta potential (210.30 ± 10.20 nm, 0.277 ± 0.01 and − 74.10 ± 0.61, respectively). ANOVA (analysis of variations) was used to analyze the responses and forecast the optimal parameters and mathematical model. The individual and combined factors, coefficients and p-values showed how each component affected the chosen responses. The relevance of the used model and other parameters evaluated by ANOVA was also shown by the p-value; a p-value of < 0.05 denotes significance. A significant quadratic model was found for every response (Table 5). The final coded regression equation of the applied quadratic model for each individual response, including particle size (Y1), PDI (Y2) and Zeta potential (Y3), generated by response surface methodology using Design Expert® software, are provided below. Figure 2 displays the 3D response surface plots of all the responses illustrating the effects of various factors.

Model fit analysis

To find the best fit model, several tests were conducted on various polynomial models, linear, interactive (2FI), quadratic, and cubic, such as using sequential model sum squares, lack of fit test, and model summary statistics. Regarding sequential model sum squares test and model summary statistics results (Table 4), it was found that 2FI and quadratic models were significant with p values of 0.0435 and < 0.0001 for PS and p values of < 0.0001 and < 0.0001 for PDI respectively. However, zeta potential showed significance with the three models (linear; p value 0.0008; 2FI, p value < 0.0001 and quadratic model; p value < 0.0001). To detect the best fit model, F values, PRESS values, adjusted R2and predicted R2 for every response should be considered and compared for all significant models as the model that exhibits higher F value, lower PRESS value with maximum adjusted R² and Predicted R² values is regarded as the best fit model46. For PS and ZP responses, higher F values were observed with quadratic model (37.88 for PS and 19.56 for ZP) opposed to that in 2FI model (2.94 for PS, 13.19 for ZP) and 6.59 for linear model in ZP, Table 4. However, F value for PDI was slightly lower in quadratic model (11.16) than that for 2FI model (12.26). Regarding PRESS values, the quadratic model showed the lowest values in all responses (20863.68 for PS, 2868.29 for PDI and 127.35 for ZP) compared to others, Table 4. For adjusted R² and Predicted R² values, quadratic model presented the maximum values in all responses (0.7660 and 0.6824 for PS, 0.6673 and 0.5245 for PDI, 0.8141 and 0.7433 for ZP) respectively, compared to other significant models, Table 4. Additionally, there is less than 0.2 discrepancy between the adjusted and predicted R2 values, indicating a reasonable level of agreement. These findings indicate that the quadratic model fits all responses the best. Because of its aliasing, the cubic model was removed and not taken into consideration. All responses showed a significant lack of fit test for the chosen model (p value < 0.0001) with unfavorable F values of 38.49 for PS, 50.51 for PDI, and 8.00 for ZP46.

ANOVA analysis

The results of the ANOVA analysis (Table 5) demonstrate the quadratic model’s relevance and adequacy for describing the relationships between variables for all responses with F values and p values of 19.19 and < 0.0001 for PS, 12.14 and < 0.0001 for PDI, 25.33 and < 0.0001 for ZP respectively. Regression Eqs. (2, 3, and 4) represent the coded models derived using response surface methodology (RSM). The variables A, B, and C are dimensionless coded values of the actual factors used to normalize the data and improve model fitting. Specifically, A corresponds to the drug amount (30–50 mg), B to the homogenization speed (6500–21,000 rpm), and C to the homogenization time (2–8 min). These models are used to assess the influence of each factor on particle size, polydispersity index (PDI), and zeta potential, furthermore, explained by 3D response surface plots (Fig. 2).

Effect of independent variables on particle size (Y1)

The prepared ETX-NCs were found to have PS values of 186.5 ± 1.8 nm to 297.9 ± 8.5 nm, Table 3. ANOVA results showed that the amount of ETX had a statistically significant effect on particle size (p = 0.0003), with an effect size of η² = 0.072. This means that approximately 7% of the variation in particle size is explained by the drug concentration, indicating a moderate impact compared to other formulation variables. Homogenization time had a significant effect on the particle size of the nanocrystals (p = 0.002), accounting for approximately 5% contribution of the variance (η² = 0.050). This indicates a small but potentially meaningful influence compared to other formulation variables. In contrast, homogenization speed showed a much smaller effect size (η² = 0.009), explaining less than 1% of the variation in particle size. This suggests that within the tested range (6500, 13,750, and 21,000 rpm), homogenization speed had a negligible impact on particle size. The polynomial equation for particle size (PS) (Y₁), presented below as Eq. 2, shows an inverse relationship with the amount of ETX, as indicated by the negative coefficient (-13.99 A). This suggests that increasing the drug concentration promotes nucleation, likely due to the greater availability of drug molecules that accelerate the formation of initial crystal nuclei. Instead of producing fewer, larger particles, this enhanced nucleation results in a higher number of smaller crystals. Moreover, the drug molecules may contribute to stabilizing the nanoparticle growth process, leading to the formation of smaller and more uniformly sized particles47,48. However, a positive relationship between homogenization time (C) and particle size was observed, with prolonged homogenization time leading to an increase in particle size. This effect can be explained by the aggregation of very fine particles, which results in the formation of larger particles over time49.

Effect of independent variables on PDI (Y2)

PDI values of all prepared NCs were between 0.252 ± 0.00 and 0.492 ± 0.00 (Table 3), so all formulations provided homogenous dispersion of NCs. Regarding the following Eq. (3), the tested levels of each independent variable have a slight effect on particles dispersion which is indicated by low coefficient values for each independent variable (Eq. 3). However, time of homogenization provides p value of 0.0008 with effect size of 0.087, indicating that approximately 8.7% of the variability in PDI can be attributed to this factor. This reflects a moderate influence within the context of the studied formulation variables.

Effect of independent variables on ZP (Y3)

Zeta potential provides an indication about stability of prepared NCs. ZP ranged between − 74.10 ± 0.61 and − 63.70 ± 0.80 (Table 3). Based on results from ANOVA, significant effect of ETX amount (p < 0.0001) and time of homogenization (p = 0.0004) was observed, where the amount of drug showed a large effect (η² = 0.238), accounting for approximately 24% of the variability. In contrast, homogenization time had a smaller impact (η² = 0.056), indicating a limited but potentially meaningful contribution to zeta potential variation. Regarding Eq. 4, a positive relation is observed between ETX amount and surface negativity50. These results are in accordance with PS results as increased drug amounts resulted in smaller particles, which have higher surface area-to-volume ratio, allowing the drug molecules and lecithin to align or arrange more effectively on the surface, thereby increasing stability51. A decrease in ZP was observed upon prolonging time of homogenization (negative coefficient with C, Eq. 4) which is attributed to agglomeration or coalescence of nanoparticles. As particles aggregate, the effective surface area decreases, reducing the exposure of charged groups responsible for maintaining a high zeta potential. This diminishes the repulsive forces between particles, leading to a drop in zeta potential.

Characterizations of prepared ETX-NCs

Drug content

It was found that the drug content in optimized NCs (F5) was 101.89 ± 0.76% w/v. According to these findings, NCs offered the drug’s maximum loading capacity.

Electron microscopy analysis

Figure 3 illustrates the morphology of pure ETX and ETX-NCs as observed through transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The ETX-NCs exhibited nanoscale particle size with a uniform distribution and a distinct cubic crystalline structure. In contrast, the unprocessed (raw) ETX displayed larger, microscale particles with smooth surfaces. These observations were further supported by SEM analysis.

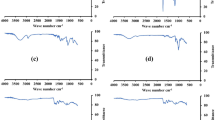

Fourier infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR)

FTIR spectroscopic analysis was performed to investigate the possible interaction and compatibility of ETX and other excipients. The results (Fig. 4, A) show the characteristic peaks of ETX as 1596.9 cm−1 (C = N stretching vibration); 1431 cm−1, 1300 cm−1, 1141.8 cm−1, and 1085.8 cm−1 (S = O stretching vibrations); and 840.9 cm−1, 775.3 cm−1, and 638 cm−1 (C-Cl stretching vibrations) respectively52. The characteristic peaks in the FT-IR spectrum of lecithin include the alkane bands that correspond to the symmetric CH2, antisymmetric CH2, antisymmetric CH3 stretching, and CH2 scissoring vibrational modes at 2854, 2928, 2956, and 1462 cm− 1, respectively; the carbonyl stretching vibration at 1736 cm− 1, and the highly overlapped PO2 − and P–O–C infrared active vibrations in the region between 1200 and 970 cm− 153. These peaks were retained in the physical mixture devoid of mannitol, demonstrating ETX’s compatibility with other components. Considering the NCs’ FT-IR spectrum, it was found that some ETX distinctive peaks (1433.3 cm−1 and 1085.4 cm−1) were retained with lower intensity while others underwent small shifts or vanished. Additionally, a distinctive lecithin peak at 1739 cm−1 disappeared along with minor shifts of others, indicating molecular interactions between ETX and lecithin in NCs that are consistent with lecithin’s stabilizing impact. Mannitol’s particular peaks were the hydroxyl function (3100–3500 cm− 1, very strong broad band), along with additional absorptions at 2935 (C–H), 1081, and 1019 cm− 1 (C–O)54. Due to the high concentration of mannitol (5%w/v), the IR spectra of the physical mixture containing mannitol mostly displayed the characteristic peaks of mannitol with the elimination of ETX and lecithin peaks. As a result, the sample was diluted.

Differential scanning colorimetry (DSC)

The DSC thermograms of ETX, lecithin, and their physical mixture (Fig. 4, C) provided complementary information regarding the thermal properties and crystallinity of ETX in the presence of lecithin. Pure ETX displayed a sharp endothermic peak at 137 °C, corresponding to its melting point, which reflects its crystalline nature55. Lecithin showed a smaller, broader peak at 126 °C, indicating its relatively lower melting point and more amorphous structure. When combined in the physical mixture (ETX and lecithin), the endothermic peaks were still observed. In the thermogram of NCs, a shift in endothermic peak of ETX to a higher melting point was observed which can be related to the lecithin-induced stabilization that resulted in improved molecular packing in the crystal lattice, this stronger crystalline lattice arrangement requires more energy to break, hence a higher melting temperature56,57,58,59. Mannitol thermogram exhibited an endothermic melting peak at 168.2 °C which still existed in NCs thermogram. Physical mixture with mannitol (ETX, lecithin and mannitol) showed a single endothermic peak typical to that of mannitol with absence of drug and lecithin peaks which related to high dilution of the sample examined with mannitol.

Powder X-ray diffraction

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was performed for pure etoricoxib (ETX), lecithin, mannitol, the physical mixture with mannitol, the physical mixture without mannitol, and the NCs formulation (Fig. 4, B). The XRD pattern of ETX displayed distinct peaks at diffraction angles of 5.46°, 11.46°, 12.54°, 14.1°, 15.96°, 17.1°, 18.66°, 19.98°, 20.1°, and 25.2°60. These characteristics to the NCs formulation, some of ETX peaks subjected to slight shifts which related to presence of mannitol, indicating its dilution. Considering XRD pattern of physical mixture with mannitol, disappearance of ETX peaks was observed or it mainly showed the characteristic peaks of mannitol only61.

Saturation solubility

Saturation solubility of ETX, Physical mixture (ETX, lecithin and mannitol) and the selected NCs formula was conducted in phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) to investigate the effect of nanocrystal form on ETX solubility. Based on the presented results (Fig. 5a), a significant increase in the saturation solubility of ETX after its inclusion as NCs (137.75 ± 1.34 µg/ml, p value < 0.001) compared to that of pure ETX and the physical mixture (87.70 ± 1.41 µg/ml and 97.95 ± 3.88 µg/ml). A slight enhancement in ETX solubility was achieved in its physical mixture form (p value < 0.05) which can be explained by the presence of mannitol in the mixture acting as a solubilizing agent for ETX through improvement its wettability62. In this study, the pH was maintained constant (7.4) to avoid any change in pH as the solubility of ETX, a pH dependent drug, may be affected by any change in the pH during the experiment.

a Solubility study of ETX, physical mixture (ETX + lecithin + mannitol) and selected NCs formula (F5), one way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis; *** (P < 0.001) and * (p < 0.05). b In vitro dissolution profiles of ETX, physical mixture (ETX + lecithin), physical mixture (ETX + lecithin + mannitol), physical mixture (ETX + mannitol) and selected NCs formula (F5), ANOVA was used for statistical analysis; *** (P < 0.001). significant increase in dissolution by NCs compared to others after 5 min.

In-vitro drug dissolution

Pure ETX, physical mixture (ETX + lecithin), physical mixture (ETX + lecithin + mannitol), physical mixture (ETX + mannitol) and selected NCs formula were subjected to dissolution study. The results (Fig. 5b) illustrated the significant role of NCs formation in enhancement of ETX dissolution, where 91.49 ± 0.01% (p value < 0.001) of drug was dissolved after the first 5 min with complete drug dissolution after 10 min. This result can be attributed to the nano-size of ETX-NCs which increase the surface area exposed for dissolution, also, presence of mannitol in the lyophilized NCs has a synergistic effect on ETX dissolution63. To investigate and confirm the effect of mannitol, different physical mixtures were studied and the results showed that, for pure ETX, physical mixture (ETX + lecithin), physical mixture (ETX + lecithin + mannitol) and physical mixture (ETX + mannitol), the % of drug dissolved were 17.87 ± 0.01%, 28.29 ± 0.03%, 56.05 ± 3.07% and 63.37 ± 1.23%, respectively after 5 min. These results approved the effect of mannitol in increasing wettability and solubilization of ETX, so improving its dissolution profile was achieved compared to pure form32,62.

Conclusion

Etoricoxib nanocrystals were prepared using acid-base precipitation method, with some modifications. Preparing conditions of 0.1% w/v of lecithin and 30 mg ETX formulated at pH 5.5 under homogenization speed 21000 rpm for 5 min were selected as the most suitable conditions for stabilization of nanocrystals with minimum particle size and PDI based on results of Box–Behnken design. The compatibility of ETX with other ingredients and its crystallinity were determined via FTIR, DSC and X-ray diffraction techniques. ETX-NCs achieved enhancing in etoricoxib saturation solubility, thereby, dissolution rate improved. Consequently, nanocrystals are a promising approach for enhancing etoricoxib properties. The pharmacokinetics of ETX-NCs and its impact on osteoarthritis are being investigated as a part of the ongoing research.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Buckley, S. T., Fischer, S. M., Fricker, G. & Brandl, M. In vitro models to evaluate the permeability of poorly soluble drug entities: challenges and perspectives. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 45, 235–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejps.2011.12.007 (2012).

Minocha, S., Pahwa, S. & Arora, V. SOlubility enhancement of poorly water soluble drugs by various techniques. J. Biomed. Pharma Res. 13–19. https://doi.org/10.32553/jbpr.v8i1.565 (2019).

Benet, L. Z. The role of BCS (biopharmaceutics classification system) and BDDCS (biopharmaceutics drug disposition classification system) in drug development. J. Pharm. Sci. 102, 34–42. https://doi.org/10.1002/jps.23359 (2013).

Kesarwani, P., Rastogi, S., Bhalla, V. & Arora, V. Solubility enhancement of poorly water soluble drugs: a review. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 5 (8), 3123–3127. https://doi.org/10.13040/IJPSR.0975-8232.5 (2014).

Joshi, J. T. A review on micronization techniques. J. Pharm. Sci. Technol. 3, 651–681 (2011).

Nikghalb, L. A., Singh, G., Singh, G. & Kahkeshan, K. F. Solid dispersion: methods and polymers to increase the solubility of poorly soluble drugs. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2, 170–175. https://doi.org/10.7324/JAPS.2012.21031 (2012).

Das, S. K., Roy, S., Kalimuthu, Y., Khanam, J. & Nanda, A. Solid dispersions: an approach to enhance the bioavailability of poorly water-soluble drugs. Int. J. Pharmacol. Pharm. Technol. 1, 37–46 (2012).

Mir, K. B. & Khan, N. A. Solid dispersion: overview of the technology. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 8, 2378–2387 (2017). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/320067986

Loftsson, T. Drug solubilization by complexation. Int. J. Pharm. 531, 276–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.08.087 (2017).

Vemula, V. R., Lagishetty, V. & Lingala, S. Solubility enhancement techniques. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res. 5, 41–51 (2010).

Al-Kassas, R., Bansal, M. & Shaw, J. Nanosizing techniques for improving bioavailability of drugs. J. Controlled Release. 260, 202–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2017.06.003 (2017).

Da Silva, F. L. O., Marques, M. B. D. F., Kato, K. C. & Carneiro, G. Nanonization techniques to overcome poor water-solubility with drugs. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 15, 853–864 https://doi.org/10.1080/17460441.2020.1750591(2020).

Sunder, S. & Nair, R. Methods of Nanonization of drugs for enhancing their dissolution. Eur. J. Adv. Eng. Technol. 3, 101–110 (2016). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/312068815

Jahangir, M. A. et al. Nanocrystals: characterization overview, applications in drug delivery, and their toxicity concerns. J. Pharm. Innov. 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12247-020-09499-1 (2020).

Patel, V., Sharma, O. P. & Mehta, T. Nanocrystal: a novel approach to overcome skin barriers for improved topical drug delivery. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 15, 351–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/17425247.2018.1444025 (2018).

Mirza, R., Ahirrao, S. & Kshirsagar, S. A nanocrystal technology: to enhance solubility of poorly water soluble drugs. J. Appl. Pharm. Res. 5, 01–13 (2017).

Pınar, S. G., Oktay, A. N., Karaküçük, A. E. & Çelebi, N. Formulation strategies of nanosuspensions for various administration routes. Pharmaceutics 15, 1520. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics15051520 (2023).

Malamatari, M., Taylor, K. M., Malamataris, S., Douroumis, D. & Kachrimanis, K. Pharmaceutical nanocrystals: production by wet milling and applications. Drug Discov. Today. 23, 534–547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drudis.2018.01.016 (2018).

Kulkarni, S. A. & Myerson, A. S. Methods for nano-crystals Preparation. Engineering Crystallography: Molecule Cryst. Funct. Form, 275–287 (2017).

Peltonen, L. & Hirvonen, J. Pharmaceutical nanocrystals by nanomilling: critical process parameters, particle fracturing and stabilization methods. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 62, 1569–1579. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2042-7158.2010.01022.x (2010).

Xie, Y. et al. Preparation and optimization of amorphous ursodeoxycholic acid nano-suspensions by nanoprecipitation based on acid-base neutralization for enhanced dissolution. Curr. Drug Deliv. 14, 483–491. https://doi.org/10.2174/1567201813666160902152122 (2017).

Prajapati, M., Yamgar, D. B., Desale, M. N. & Fegade, B. A. Review on various analytical methodologies for etoricoxib. Adv. J. Grad. Res. 11, 61–70. https://doi.org/10.21467/ajgr.11.1.61-70 (2022).

Srinivasan, S. et al. Preparation and characterization of Etoricoxib ternary complex for the enhancement of solubility. J. Pharm. Negat. Results, 14, 1703–1712 (2023).

Cochrane, D. J., Jarvis, B. & Keating, G. M. Etoricoxib. Drugs 62, 2637–2651 (2002).

Mitra, A., Kesisoglou, F. & Dogterom, P. Application of absorption modeling to predict bioequivalence outcome of two batches of etoricoxib tablets. AAPS PharmSciTech. 16, 76–84. https://doi.org/10.1208/s12249-014-0194-8 (2015).

Sharma, A. et al. in AIP Conference Proceedings. (AIP Publishing).

Ashokbhai, M. K. et al. Leveraging solid solubility and miscibility of etoricoxib in Soluplus® towards manufacturing of 3D printed etoricoxib tablets by additive manufacturing. Int. J. Pharm. 667, 124881. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2024.124881 (2024).

Nayak, A. K. & Panigrahi, P. P. Solubility enhancement of etoricoxib by cosolvency approach. Int. Sch. Res. Not., 2012, 820653. https://doi.org/10.5402/2012/820653 (2012).

Elsegaie, D., El-Nabarawi, M. A., Mahmoud, H. A., Teaima, M. & Louis, D. A. Comparative study on cyclodextrin derivatives in improving oral bioavailability of etoricoxib as a model drug: formulation and evaluation of solid dispersion-based fast-dissolving tablets. Biomedicines 11, 2440. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines11092440 (2023).

Yu, Q. et al. Enhanced transdermal delivery of meloxicam by nanocrystals: preparation, in vitro and in vivo evaluation. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 13, 518–526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajps.2017.10.004 (2018).

Villalva, D. G., França, C. G. & Loh, W. Characterization of cubosomes immobilized in hydrogels of hyaluronic acid and their use for diclofenac controlled delivery. Colloids Surf. B. 212, 112352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfb.2022.112352 (2022).

Das, A., Nayak, A. K., Mohanty, B. & Panda, S. Solubility and dissolution enhancement of etoricoxib by solid dispersion technique using sugar carriers. Int. Sch. Res. Not.. 2011, 819765. https://doi.org/10.5402/2011/819765 (2011).

Aldawsari, H. M., Alhakamy, N. A., Padder, R., Husain, M. & Md, S. Preparation and characterization of Chitosan coated Plga nanoparticles of resveratrol: improved stability, antioxidant and apoptotic activities in H1299 lung cancer cells. Coatings 10, 439. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings10050439 (2020).

Amjadi, S., Almasi, H., Ghorbani, M. & Ramazani, S. Preparation and characterization of TiO2NPs and betanin loaded zein/sodium alginate nanofibers. Food Packag. Shelf Life. 24, 100504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fpsl.2020.100504 (2020).

Wen, K. et al. Preparation and characterization of PLGA nano-drug delivery system co-loaded with tranilast/gallium phytate for stent coating. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 97, 105812. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jddst.2024.105812 (2024).

Silva-Abreu, M. et al. Stabilization by nano spray dryer of Pioglitazone polymeric nanosystems: development, in vivo, ex vivo and synchrotron analysis. Pharmaceutics 13, 1751. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics13111751 (2021).

Zaid Alkilani, A., Musleh, B., Hamed, R., Swellmeen, L. & Basheer, H. A. Preparation and characterization of patch loaded with clarithromycin nanovesicles for transdermal drug delivery. J. Funct. Biomater.. 14, 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb14020057 (2023).

Chen, H., Wang, R. & McElderry, J. D. Discriminative dissolution method development through an aQbD approach. AAPS PharmSciTech. 24, 255. https://doi.org/10.1208/s12249-023-02692-8 (2023).

Mouzouvi, C. R., Umerska, A., Bigot, A. K. & Saulnier, P. Surface active properties of lipid nanocapsules. PLoS One. 12, e0179211. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0179211 (2017).

Xu, Q., Nakajima, M., Liu, Z. & Shiina, T. Soybean-based surfactants and their applications. Soybean-applications Technol. 341–364 (2011).

Sajeev Kumar, B. et al. Development and characterization of lecithin stabilized Glibenclamide nanocrystals for enhanced solubility and drug delivery. Drug Deliv. 21, 173–184. https://doi.org/10.3109/10717544.2013.840690 (2014).

Ruiz-Agudo, C., Putnis, C. V., Ruiz-Agudo, E. & Putnis, A. The influence of pH on barite nucleation and growth. Chem. Geol. 391, 7–18 (2015).

Mullin, J. W. Crystallization. (Elsevier, 2001).

Kukushkin, S. & Nemna, S. in Doklady Physical Chemistry. 117–120 (Springer).

Starek, M. Review of the applications of different analytical techniques for Coxibs research. Talanta 85, 8–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.talanta.2011.04.052 (2011).

Parhi, R. & Goli, V. N. Design and optimization of film-forming gel of Etoricoxib using research surface methodology. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 10, 498–514. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13346-019-00695-2 (2020).

Kakran, M. et al. Fabrication of drug nanoparticles by evaporative precipitation of nanosuspension. Int. J. Pharm. 383, 285–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2009.09.030 (2010).

Tian, M., Guo, J., Wang, Z., Cao, J. & Gong, X. Synergetic effect of secondary nucleation and growth on the lithium carbonate particle size in the gas–liquid reactive crystallization of LiCl–NH3· H2O–CO2. Particuology 51, 10–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.partic.2019.10.006 (2020).

Lamprecht, A. et al. Influences of process parameters on nanoparticle preparation performed by a double emulsion pressure homogenization technique. Int. J. Pharm. 196, 177–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-5173(99)00422-6 (2000).

Govender, T., Stolnik, S., Garnett, M. C., Illum, L. & Davis, S. S. PLGA nanoparticles prepared by nanoprecipitation: drug loading and release studies of a water soluble drug. J. Controlled Release. 57, 171–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-3659(98)00116-3 (1999).

Jun, J. Y., Nguyen, H. H., Chun, H. S., Kang, B. C. & Ko, S. Preparation of size-controlled bovine serum albumin (BSA) nanoparticles by a modified desolvation method. Food Chem. 127, 1892–1898. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.02.040 (2011).

Sapkal, S. B. et al. Formulation and characterization of solid dispersions of Etoricoxib using natural polymers. Turk. J. Pharm. Sci. 17, 7. https://doi.org/10.4274/tjps.galenos.2018.04880 (2020).

Kuligowski, J., Quintás, G., Garrigues, S. & De la Guardia, M. Determination of lecithin and soybean oil in dietary supplements using partial least squares-Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Talanta 77, 229–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.talanta.2008.06.029 (2008).

Rajbanshi, K., Bajracharya, R., Shrestha, A. & Thapa, P. Dissolution enhancement of aceclofenac tablet by solid dispersion technique. Int. J. Pharma Sci. Res. 5, 127–139 (2014).

Kulthe, V. V. & Chaudhari, P. D. Characterization of etoricoxib solid dispersions prepared by spray drying technique. Res. J. Pharm. Technol. 3, 1158–1166 (2010).

Xiao, S., Hu, W. & Yang, J. Melting temperature: from nanocrystalline to amorphous phase. J. Chem. Phys. 125 https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2371112 (2006).

Al Rsheed, A., Aldawood, S. & Aldossary, O. M. The size and shape effects on the melting point of nanoparticles based on the Lennard-Jones potential function. Nanomaterials 11, 2916 (2021). https://doi.org/10.3390/nano11112916

Turchanin, M. & Agraval, P. Cohesive energy, properties, and formation energy of transition metal alloys. Powder Metall. Met. Ceram. 47, 26–39 (2008).

Ferrar, J. A., Sellers, B. D., Chan, C. & Leung, D. H. Towards an improved understanding of drug excipient interactions to enable rapid optimization of nanosuspension formulations. Int. J. Pharm. 578, 119094. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2020.119094 (2020).

Chowdhury, S. et al. Preparation, physicochemical characterization and dissolution studies of etoricoxib-(beta)-cyclodextrin complexes. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 7, 424–433 (2012).

Zhang, T. et al. Preparation, characterization, and evaluation of breviscapine nanosuspension and its freeze-dried powder. Pharmaceutics 14, 923. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics14050923 (2022).

Zhang, K. et al. Specific surface area of mannitol rather than particle size dominant the dissolution rate of poorly water-soluble drug tablets: A study of binary mixture. Int. J. Pharm. 660, 124280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2024.124280 (2024).

Pomázi, A., Ambrus, R., Sipos, P. & Szabó-Révész, P. Analysis of co-spray-dried meloxicam–mannitol systems containing crystalline microcomposites. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 56, 183–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpba.2011.05.008 (2011).

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the gift sample of etoricoxib from APEX PHARMA, Cairo, Egypt.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Methodology, L.M.A, Software, L.M.A; Conceptualization, T.H.E, F.A.M and L.M.A; Validation, T.H.E, F.A.M and L.M.A; Formal analysis, T.H.E and L.M.A; Investigation, T.H.E and F.A.M; Writing original draft, L.M.A; Review & Editing, T.H.E, F.A.M, L.M.A; Supervision, T.H.E and F.A.M; Project administration, T.H.E and L.M.A.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmed, L.M., Mohamed, F.A. & Elfaham, T.H. Nanocrystals as a promising approach for enhancing solubility and dissolution of etoricoxib using Box–Behnken design. Sci Rep 15, 29347 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12837-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12837-3