Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused over 7 million deaths worldwide, with age, underlying conditions, and immunosuppression increasing the incidence of severe outcomes. Despite vaccination, immunocompromised (IC) individuals show lower vaccine response, probably leading to more breakthrough infections. The objective of our study was to evaluate the overall occurrence of intensive care admission and/or death during hospitalisation, stratified by COVID-19 severity and immunological status (IC vs. non-IC individuals). Our study used a nationwide database to compare COVID-19 hospitalisations and outcomes in IC versus non-immunocompromised individuals (non-IC). This is a longitudinal cohort study analysed de-identified COVID-19 data from Brazil’s DATASUS system (02 March 2020–31 December 2023). The study included 361,898 subjects, identifying 7484 (2.07%) IC individuals. IC individuals showed higher rates of chronic liver, neurological, and lung diseases, while non-IC individuals had higher obesity rates. Intensive care unit (ICU) admissions (42.6% vs. 38.5%) and mortality (51.1% vs. 35.9%) were greater in IC compared to non-IC individuals. Therefore, IC individuals consistently experienced more ICU admissions and higher mortality across the COVID-19 pandemic years (odds ratios rising from 1.68 in 2020 to 2.39 in 2023), influenced by the prevalence of SARS-Cov-2 variants. Our study shows higher morbidity and mortality in IC individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic, underscoring the need for targeted strategies like early interventions, reinforcing the need for sustained surveillance, targeted vaccination strategies, and prioritised care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global pandemic caused by the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) has led to more than 7.0 million deaths since its emergence1. Factors such as age, underlying health conditions, such uses of previous or ongoing immunosuppressive treatments increase the risk of COVID-19 infection and resulting severe outcomes, including hospitalization and death2,3,4,5.

During COVID-19 pandemia the mitigation strategies such as border closures, lockdowns, social distancing, widespread testing, and vaccination campaigns were implemented globally, leading to a reduction in transmission and mortality6. Following the declaration of the end of the global pandemic in May 2023, there has been a progressive scaling back of public health interventions7. However, even after pandemia there is a lack of sufficient data on the ongoing impact of COVID-19 in immunosuppressive (IC) individuals, who remain significantly affected throughout Brazil. Despite making up a relatively small segment of the population, IC individuals experience a disproportionately high rate of severe COVID-19 outcomes, resulting in substantial healthcare burden based on higher length of stay (LoS) and death compared to immunocompetent (non-IC) individuals8.

As an example of the COVID-19 burden among IC individuals, lung cancer stands out, with patients exhibiting a higher mortality rate (57.1%) compared to those with other solid tumors (32.2%)9. This risk is particularly elevated in individuals recently diagnosed with cancer, compared to those with a longer disease history10, highlighting the acute phase of solid tumors as a critical period of increased vulnerability to severe COVID-19. Similarly, hematological malignancies contribute to higher LoS and mortality, with acute myeloid leukaemia showing a higher mortality rate compared to lymphoproliferative disorders3.

In other immuno-compromised clinical scenarios, studies have emphasized that recipients of solid organ transplants (SOT) face significantly higher mortality rates and LoS compared to the general population. In particular, found that SOT patients hospitalised with COVID-19 experienced a substantially increased mortality rate, with recipients of kidney, lung, liver, and combined transplants all showing elevated risk11,12. On the other hand, for immunosuppressive viruses such as HIV/AIDS, data on LoS and mortality compared to non-IC individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic remain conflicting, irrespective of the predominant SARS-CoV-2 variant13.

Mass vaccination efforts played a central role in reducing the global burden of COVID-19, enabling populations worldwide to gradually return to normal life. However, IC individuals, who exhibit weaker immune responses to vaccination, may become increasingly vulnerable to COVID-19 risks as the effectiveness of public health measures diminishes14,15,16,17. Throughout the pandemic, various variants of concern have circulated in Brazil18,19, potentially influencing hospitalisation rates, LoS and mortality, particularly among IC individuals, an issue that is still debatable.

Given the limited evidence on the burden of COVID-19 among IC individuals, this study aimed to evaluate the overall incidence of intensive care unit (ICU) admission and/or in-hospital mortality, stratified by COVID-19 severity and immunological status (IC vs. non-IC), using data from Brazil’s national public healthcare system across periods dominated by five distinct SARS-CoV-2 variants.

Materials and methods

Study design and data sources

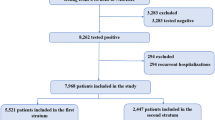

This observational, longitudinal and descriptive study is based on secondary databases from Brazil’s Unified Health System (SUS) database (DATASUS)20. Data were collected from three public databases, including DATASUS SRAG21 (severe acute respiratory syndrome), DATASUS SIH22 (Hospital Information System), and DATASUS Imunizações23 (DATASUS immunization data) and were submitted to linkage process.

The SRAG database captures all hospitalised cases of severe acute respiratory infections, including COVID-19, in public and private health care facilities across Brazil. It provides individual-level, anonymised data on age, sex, race/ethnicity, municipality of residence and hospitalisation, symptom onset, admission and discharge dates, ICU use, comorbidities, diagnostic test results, and clinical outcomes (recovery or death). Each case is assigned a unique identifier, enabling internal tracking while preserving patient confidentiality. Only cases with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 and complete outcome data were included in this analysis.

The SIH database contains administrative and clinical records for all hospitalisations reimbursed by the SUS, including admissions to public hospitals and private institutions under SUS contract. The database includes hospital codes, geographic location, admission/discharge dates, LoS, ICD-10-coded diagnoses, and procedures, including ICU admissions. SIH data were used to validate hospitalization patterns, ICU use, and length of stay among COVID-19 patients.

The DATASUS Imunizações dataset contains individual-level vaccination records, including vaccine type, dose dates, and administration location. This system enables nationwide tracking of immunization status across all age groups.

For this study, DATASUS Imunizações data were linked to SRAG records using anonymised individual identifiers to assess vaccination coverage among IC and non-IC individuals. No personally identifiable information (e.g., name, address, or national ID number) is accessible in the publicly released dataset.

Study population

The study population consisted of IC individuals hospitalised exclusively for COVID-19 between March 2, 2020, and December 31, 2023. This cohort represents a substantial sample of COVID-19 cases documented in the Brazilian public health registry system. Individuals with missing values were excluded from analysis to ensure data completeness. For analytical purposes, the population was further divided into two groups: IC and non-IC individuals.

The IC individuals included in the study were patients presenting a primary immunodeficiency, secondary immunodeficiency, high-dose, long-term moderate dose corticosteroids treatment, end-stage kidney disease or dialysis, organ transplants in the last five years, stem cell transplants, solid tumors in the last five years, haematological malignancies in the last five years, and HIV/AIDS. The specific criteria and definitions used to classify individuals as IC are detailed in the Supplementary Material, Supplement 1, which provides additional context on classification and group allocation within the study population based on ICD-10-coded diagnoses.

Clinical characteristics and outcomes

Clinical characteristics included sex, age, and predefined age strata (< 18, 18–64, 65–69, 70–79, and ≥ 80 years), based on prior studies identifying age-related risk patterns in COVID-19 outcomes24,25. Clinical covariates included the presence of key comorbidities: asthma, postpartum, diabetes, obesity, chronic heart disease, chronic liver disease, chronic neurological conditions, Down syndrome, chronic liver diseases, and chronic respiratory disease.

The outcomes included the combined incidence of ICU admission and/or in-hospital death among IC versus non-IC individuals, with secondary analyses stratified by year and LoS, particularly focusing on ICU use across study groups. Additionally, we analysed hospital admission dates, in-hospital mortality, LoS (in days), and ICU admissions, including the impact of COVID-19 variants and vaccination status.

Statistical analysis

Clinical characteristics of groups were presented in descriptive tables, providing a detailed overview of each subgroup’s attributes. For numerical variables, such as age, the mean and standard deviation were calculated. In the case of categorical variables (e.g., sex, comorbidities), both absolute counts and per cents were reported. Hospitalisation LoS was analysed with a focus on the median value, alongside the 25th (Q1) and 75th (Q3) percentiles. Additionally, data were further stratified by the COVID-19 period to capture differences across pandemic phases. To assess differences in baseline characteristics between IC and non-IC groups, p-values were calculated using the Chi-square test for categorical variables and Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables. These values are presented in Table 1.

To evaluate the main outcomes, we performed both unadjusted and multivariable logistic regression analyses, calculating odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). The multivariable models adjusted for age, sex, key comorbidities, and COVID-19 vaccination status. These adjustments were incorporated to reduce potential confounding in the association between immunosuppressed status and the outcomes of ICU admission and in-hospital mortality. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. Analyses were performed using R software.

Comparations regarding mortality and ICU admissions between groups (IC vs. non-IC), a cubic spline regression was performed using the percentiles of LoS as the independent variable and the prevalence of outcomes (mortality and ICU admissions) as the dependent variable. It was calculated the mean difference between points in the regression, represented by \(\:\overline{{\Delta\:}{\text{P}}_{{\text{x}}_{\text{i}}}}\).

For the IC population, hospital mortality due to COVID-19 is predicted to be 19%. According to Brazilian indicators, the IC population rate is 1% in Brazil. In the DATASUS database, we have around 60 to 70 thousand records about hospitalisations in Brazil. According to the table in Supplementary Table 1S, the accuracy for different expected scenarios is calculated. Thus, a precision of 2% is expected in the scenario of 19% of hospital mortality due to COVID-19 in the IC population with 6.000 samples and a 95% CI expected is 18 to 20%.

The p-value of < 0.05 was assumed as significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using R software.

Ethics

The datasets were validated by removing duplicate entries and ensuring the consistency and completeness of the registered data, in compliance with the guidelines from Research Ethics of the National Health Council, Brazil. Written informed consent was not required for participation in this study, in accordance with national legislation and institutional regulations.

Reporting

We followed the checklist of the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology to report our data26.

Results

Study population demographics and COVID-19 variants

The study population consisted of 361,898 subjects (Table 1), of which 2.07% were IC individuals (n = 7484). The male group was slightly larger than the female group, and IC individuals had a lower median age compared to the non-IC group. Some clinical comorbidities prevalence, including asthma, diabetes, and chronic heart disease were not different between IC vs. non-IC groups. The non-IC group showed a higher prevalence of obesity compared to the IC group (10.0% vs. 7.7%), whereas the IC group exhibited higher prevalences of chronic liver disease (4.2% vs. 0.7%), chronic neurological disease (6.1% vs. 3.3%), and chronic pneumopathy (8.2% vs. 3.3%), as expected.

The distribution of sex and age stays quite even between groups, besides the year stratification. The year-stratified data reveals the most prevalent COVID-19 variant for each year as follows: Alpha and other in 2020, co-dominance of Gamma and Delta in 2021 , Omicron in 2022 and Omicron XBB in 2023 (Table 2).

Length of stay and ICU admission

Regarding LoS, the median values were comparable between the IC and non-IC groups (Table 1). However, when LoS was stratified into day ranges, IC group revels more LoS exceeding 7 days compared to non-IC in all years analysed (Table 2).

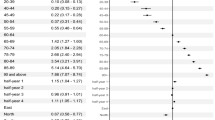

Overall, ICU admission data shows a modestly greater incidence in IC group (42.6%) compared to non-IC group (38.5%). For all subjects the odds ratio for ICU admission decreases alongside years (Supplementary Material, Table S2), however, the IC group demonstrated a higher likelihood of ICU admission over the years compared to the non-IC group (Fig. 1), however, in 2022 and 2023, the odds of ICU admission did not differ between the IC and non-IC groups (p > 0.05) may be influenced by external factors not accounted for in our analysis (Supplementary Material, Table 3 S).

(A) ICU admission due to COVID-19, stratified by year and immunologic status. The fire shows that IC individuals were admitted to ICU more frequently, with a trend towards reducing the ICU admissions among both groups (IC and non-IC). (B) In-hospital mortality due to COVID-19, stratified by year and immunologic status. The figure shows that COVID-19 had a greater mortality among IC patients over the years, with a trend towards reducing the mortality among both groups (IC and non-IC).

Mortality

The overall incidence of death during the study period was higher in the IC group compared with the non-IC group (51.1% vs. 35.9%, respectively; Table 1). In the general population, the odds ratio progressively declined over the study period (Supplementary Table 2 S). However, mortality rates remained largely stable across all years in both groups, with consistently higher rates observed in the IC group (Fig. 1B). Specifically, the odds of mortality in the IC group were 1.68 (95% CI 1.55–1.83) in 2020, increasing to 2.39 (95% CI 1.53–3.71) in 2023 (Supplementary Table 3 S).

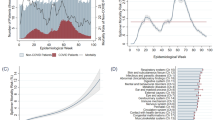

Impact of length of stay in mortality

We provide an analysis using spline regressions of prevalence of death vs. percentiles of LoS. This analysis was stratified by year and the mean \(\:\overline{{\Delta\:}{\text{P}}_{{\text{x}}_{\text{I}}}}\), was calculated for each year. Of notice, the difference between points of each slope remains near the mean value, presented in the centre of the graphics (Fig. 2). The \(\:\overline{{\Delta\:}{\text{P}}_{{\text{x}}_{\text{I}}}}\) around the mean value indicates that the difference in mortality prevalence between IC and non-IC individuals remains relatively constant, particularly beyond the 30th percentile (approximately four days of in-hospital care) for each year of follow-up, as observed in 2020 (Fig. 2A), 2021 (Fig. 2B), 2022 (Fig. 2C), and 2024 (Fig. 2D). Also, the slopes of spline regression stay flat starting at the fourth day of in-hospital stay, which shows that the prevalence of death does not vary in function to the LoS after the fourth day of in-hospital admission. Notably, the mean distance between points on the slope increases over the years, likely due to a decline in non-IC mortality rates.

Spline regression with the independent variable being the LoS and the dependent variable being the prevalence of death, for the year of 2020 (A), 2021 (B), 2022 (C) and 2023 (D). The two lines represent IC and non-IC individuals. The \(\:\overline{{\Delta\:}{\text{P}}_{{\text{x}}_{\text{i}}}}\) represents the mean distance between points of the spline regression. It is of notice that the regression slope stays flat after the fourth day of in-hospital stay for all of the years analysed. The \(\:\overline{{\Delta\:}{\text{P}}_{{\text{x}}_{\text{i}}}}\) increase along the years at the cost of reduction of mortality in non-IC individuals.

Discussion

Our findings revel that the IC individuals did have worse outcomes regarding ICU admission and death when compared to non-IC individuals during three waves of COVID-19 pandemic, independent of SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern. This data from Brazilian public health system sustain how severe was the pandemics regarding mortality and ICU admissions, especially for those with immunological system compromised.

The balanced distribution of age and sex across both IC and non-IC groups reinforce the validity of comparing outcomes directly, as these are potential confounding factors in COVID-19 severity27,28. The increased prevalence of chronic liver disease29, neurological conditions30, and pneumopathy31 among IC individuals, in our sample, may be relevant impact to adverse outcomes in COVID-19 infections32. By contrast, a higher prevalence of obesity in non-IC individuals suggests that, while obesity is an important risk factor in COVID-19, the heightened risk among IC individuals may be driven more by underlying immunological vulnerabilities than by metabolic factors.

The median LoS was comparable between groups; however, IC individuals were more likely to experience prolonged hospitalisations. Specifically, 54.2% of IC individuals had stays exceeding seven days compared to only 44.9% of non-IC individuals, indicating a greater healthcare burden within the IC population. This prolonged LoS among IC individuals likely reflects the increased complexity of managing COVID-19 in this group, who often experience extended recovery times and complications from comorbidities and immune suppression. ICU admission odds were also notably higher among IC patients, though the significance diminished across the years in a stratified analysis by year33,34. A retrospective cohort study analysing ICU admissions between March and May 2020, based on data from the COVID-19 Hospitalisation in England Surveillance System35, reported a median LoS between 10 and 12 days, however, in the same country another study including patients between August 2020 to January 2022 revels that LoS among patients who required critical care, the median LoS was 8 days36, similar to our findings, may reflect adaptations in COVID-19 management over time, driven by advancements in vaccines, antiviral therapies, and care protocols.

As expected, the mortality rate among IC individuals was significantly higher than that of non-IC individuals. These findings underscore the continued vulnerability of IC populations. It is worth highlighting that our population was composed of more severe cases, for instance, patients who suffered a breakthrough infection and that were hospitalised. Mortality differences revealed persistent gaps in mortality prevalence between IC and non-IC groups. Our findings suggest a sustained vulnerability in IC individuals, where mortality risk persists over time and does not decrease with prolonged in-hospital care. Although spline regression trends suggest persistent differences in mortality between IC and non-IC groups over the years, these findings are descriptive and not adjusted for potential confounders such as age, comorbidities, or vaccination status. Therefore, causal interpretations should be made with caution4,31. However, a recent meta-analysis demonstrated significantly higher COVID-19 mortality risk in patients with solid organ transplants (OR 2.12, 95% CI 1.50–2.99) and malignancies (OR 2.02, 95% CI 1.69–2.42), with moderately elevated risk in those with rheumatological conditions (OR 1.28, 95% CI 1.13–1.45) or HIV (OR 1.20, 95% CI 1.05–1.36), compared to immunocompetent individuals37. These findings suggest that excess mortality is more strongly associated with specific immunosuppressed subgroups and the predominance of particular SARS-CoV-2 variants.

In general, the introduction of vaccination during the pandemic provided greater security for the population, including high-risk groups, and served as an important adjunct to behaviors that incorporated preventive strategies against COVID-1937. However, it is important to emphasise that traditionally high-risk groups continued to demonstrate greater vulnerability in most studies38,39, including ours. IC individuals consistently exhibited significantly higher mortality rates compared to the general population following hospitalisation during the pandemic years.

These findings underscore that, despite the progress achieved through vaccination and preventive measures during the COVID-19 pandemic, the impact on the IC population requires heightened attention. This group not only maintained its high vulnerability but also continued to face significant challenges regarding survival following hospitalisation, particularly in severe infection conditions.

Our study has some strengths. This study is based on national public database analysis reflecting COVID-19 pandemic impact in IC individuals across three consecutive years. Thus, our findings might help with implementation of distinct clinical and social management of high-risk subjects, in case of future severe respiratory infection outbreak. Despite the strengths, some limitations apply: our analysis is based on data from a national public health database, which may be subject to inherent limitations, including data entry errors, missing or inconsistent information, and potential misclassification. These issues could introduce selection bias and affect the completeness and accuracy of the findings. However, to mitigate the risk of bias associated with the data linkage process, we implemented and validated subject identification criteria across databases. This approach enhanced data quality but resulted in a reduced sample size and statistical analysis power. We did not account for the competing risk of death when measuring time of LoS. Given the higher mortality observed for IC individuals hospitalised compared to those non-IC during follow-up, we believe that the reported rate ratios are likely to underestimate the differences. We cannot entirely rule out the possibility of a relative vaccine bias. Therefore, effect estimates for IC and non-IC conditions, particularly those related to the COVID-19 vaccination booster over the years, are susceptible to such biases. If present, this bias would imply that the estimated waning effects are likely conservative relative to the true waning effects. Another point to consider is that hypertension is a well-established risk factor for mortality in COVID-19 patients. However, data on patients with a history of hypertension prior to hospital admission were not available in the DATASUS database used for this analysis, nor were key clinical variables such as oxygen supplementation, laboratory results, or composite measures of comorbidity (e.g., Charlson Comorbidity Index).This limitation may affect the assessment of classical risk factors’ impact on iIC individuals hospitalized due to COVID-19.

Conclusion

Our findings show that IC individuals had modestly higher ICU admission rates and more frequent prolonged hospital stays. Mortality in this group increased over time, with odds ratios rising from 1.68 in 2020 to 2.39 in 2023, across three pandemic waves—highlighting the sustained vulnerability of this population despite widespread vaccination efforts.

Based on data from Brazil’s public health system, these results highlight the disproportionate vulnerability of IC populations and reinforce the need for sustained surveillance, targeted vaccination strategies, and prioritized care. As health systems shift beyond the acute phase of the pandemic, such insights are critical to inform future preparedness efforts and ensure that high-risk groups remain central in public health responses.

Data availability

Requests for materials should be addressed to H.A.F.

References

COVID-19 deaths | WHO COVID-19 dashboard. datadot. https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/cases

Marques, C. D. L. et al. High levels of immunosuppression are related to unfavourable outcomes in hospitalised patients with rheumatic diseases and COVID-19: first results of reumacov Brasil registry. RMD Open. 7, e001461 (2021).

Pio-Abreu, A. et al. High mortality of CKD patients on Hemodialysis with Covid-19 in Brazil. J. Nephrol. 33, 875–877 (2020).

Pagano, L. et al. COVID-19 infection in adult patients with hematological malignancies: a European hematology association survey (EPICOVIDEHA). J. Hematol. Oncol. J. Hematol. Oncol. 14, 168 (2021).

Cavalcanti, I. D. L. & Soares, J. C. S. Impact of COVID-19 on cancer patients: A review. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Oncol. 17, 186–192 (2021).

Hirt, J., Janiaud, P. & Hemkens, L. G. Randomized trials on non-pharmaceutical interventions for COVID-19: a scoping review. BMJ Evid. -Based Med. 27, 334–344 (2022).

Sarker, R. et al. The WHO has declared the end of pandemic phase of COVID-19: way to come back in the normal life. Health Sci. Rep. 6, e1544 (2023).

Bytyci, J., Ying, Y. & Lee, L. Y. W. Immunocompromised individuals are at increased risk of COVID-19 breakthrough infection, hospitalization, and death in the post‐vaccination era: A systematic review. Immun. Inflamm. Dis. 12, e1259 (2024).

Lemos, A. E. G., Silva, G. R., Gimba, E. R. P. & Matos, A. R. Susceptibility of lung cancer patients to COVID-19: A review of the pandemic data from multiple nationalities. Thorac. Cancer. 12, 2637–2647 (2021).

Steinberg, J. et al. Risk of COVID-19 death for people with a pre-existing cancer diagnosis prior to COVID-19-vaccination: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Cancer. 154, 1394–1412 (2024).

Linares, L. et al. A propensity score-matched analysis of mortality in solid organ transplant patients with COVID-19 compared to non-solid organ transplant patients. PLoS One. 16, e0247251 (2021).

Rees, E. M. et al. COVID-19 length of hospital stay: a systematic review and data synthesis. BMC Med. 18, 270 (2020).

SeyedAlinaghi, S. et al. COVID-19 mortality in patients with immunodeficiency and its predictors: a systematic review. Eur. J. Med. Res. 27, 195 (2022).

Chavarot, N. et al. Weak antibody response to three doses of mRNA vaccine in kidney transplant recipients treated with Belatacept. Am. J. Transpl. Off J. Am. Soc. Transpl. Am. Soc. Transpl. Surg. 21, 4043–4051 (2021).

Boongird, S. et al. Short-Term immunogenicity profiles and predictors for suboptimal immune responses in patients with End-Stage kidney disease immunized with inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. Infect. Dis. Ther. 11, 351–365 (2022).

Barabino, L. et al. Chronic graft vs. host disease and hypogammaglobulinemia predict a lower immunological response to the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 26, 8984–8989 (2022).

Barnes, E. et al. SARS-CoV-2-specific immune responses and clinical outcomes after COVID-19 vaccination in patients with immune-suppressive disease. Nat. Med. 29, 1760–1774 (2023).

Duong, B. V. et al. Is the SARS CoV-2 Omicron variant deadlier and more transmissible than Delta variant? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19, 4586 (2022).

Alves, H. J. et al. Monitoring the establishment of VOC gamma in Minas gerais, Brazil: A retrospective epidemiological and genomic surveillance study. Viruses 14, 2747 (2022).

DATASUS—Ministério da Saúde. https://datasus.saude.gov.br/

SRAG 2021 a. 2024—Banco de Dados de Síndrome Respiratória Aguda Grave—incluindo dados da COVID-19—OPENDATASUS. https://opendatasus.saude.gov.br/dataset/srag-2021-a-2024

Morbidade Hospitalar do SUS (SIH/SUS).—DATASUS. https://datasus.saude.gov.br/acesso-a-informacao/morbidade-hospitalar-do-sus-sih-sus/

Imunizações—Doses Aplicadas—Brasil. http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br/cgi/dhdat.exe?bd_pni/dpnibr.def

Yanez, N. D., Weiss, N. S., Romand, J. A. & Treggiari, M. M. COVID-19 mortality risk for older men and women. BMC Public. Health. 20, 1742 (2020).

Levin, A. T. et al. Assessing the age specificity of infection fatality rates for COVID-19: systematic review, meta-analysis, and public policy implications. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 35, 1123–1138 (2020).

von Elm, E. et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 61, 344–349 (2008).

Dettori, S. et al. COVID-19 throughout pandemic waves and virus variants: a real-life experience in an Italian hospital. J. Chemother. Florence Italy https://doi.org/10.1080/1120009X.2024.2384321 (2024).

Alamdari, N. M. et al. Mortality risk factors among hospitalized COVID-19 patients in a major referral center in Iran. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 252, 73–84 (2020).

Aby, E. S. et al. Long-term clinical outcomes of patients with COVID-19 and chronic liver disease: US multicenter COLD study. Hepatol. Commun. 7, e8874 (2023).

Bazylewicz, M., Gudowska-Sawczuk, M., Mroczko, B., Kochanowicz, J. & Kułakowska, A. COVID-19: the course, vaccination and immune response in people with multiple sclerosis: systematic review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 9231 (2023).

Bhattacharyya, A., Seth, A., Srivastava, N., Imeokparia, M. & Rai, S. Coronavirus (COVID-19): A systematic review and Meta-analysis to evaluate the significance of demographics and comorbidities. Res Sq Rs 3 Rs. -144684 (2021).

Castilla, J. et al. Risk factors of infection, hospitalization and death from SARS-CoV-2: A population-based cohort study. J. Clin. Med. 10, 2608 (2021).

Batista, M. J. et al. COVID-19 mortality among hospitalized patients: survival, associated factors, and Spatial distribution in a City in São paulo, Brazil, 2020. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 21, 1211 (2024).

Xie, Y., Choi, T. & Al-Aly, Z. Postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection in the Pre-Delta, delta, and Omicron eras. N Engl. J. Med. 391, 515–525 (2024).

Shryane, N. et al. Length of stay in ICU of Covid-19 patients in england, March-May 2020. Int. J. Popul. Data Sci. 5, (2021).

Yang, J. et al. Healthcare resource utilisation and costs of hospitalisation and primary care among adults with COVID-19 in england: a population-based cohort study. BMJ Open. 13, e075495 (2023).

Leston, M. et al. Disparities in COVID-19 mortality amongst the immunosuppressed: A systematic review and meta-analysis for enhanced disease surveillance. J. Infect. 88, 106110 (2024).

Bertini, C. D., Khawaja, F. & Sheshadri, A. Coronavirus disease-2019 in the immunocompromised host. Clin. Chest Med. 44, 395–406 (2023).

Barouch, D. H. Covid-19 Vaccines—Immunity, variants, boosters. N Engl. J. Med. 387, 1011–1020 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Andrew Lee for his valuable contributions to the data analysis and Dr Leonardo Arcuri for his critical review of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by Astrazeneca through a grant awarded to Academic Research Organization (ARO-Einstein) by grant number: Astrazeneca-D7000R00020.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.A.R.F., J.E.R.B., L.D.S. and M.M.S. conceptualised the study. M.L., G.C., F.M. and G.P.C. conducted the analyses. H.A.R.F., L.F.T.S., A.J.C.M. and J.E.R.B. drafted the manuscript. H.A.R.F., J.E.R.B., L.D.S., M.M.S. and L.V.R. supervised the analysis and data interpretation. L.F.T.S. and H.A.R.F. wrote the final manuscript. All the authors had access to the data in the study, contributed to the data interpretation and discussion and approved the final manuscript version. We stated that all the authors had access to the data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fonseca, H.A.R., Theotonio dos Santos, L.F., Mattos, A.J.C. et al. Nationwide longitudinal analysis of COVID-19 hospitalisation burden in immunocompromised patients. Sci Rep 15, 34027 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12847-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12847-1