Abstract

Lithium manganese phosphate (LiMnPO4) is the most promising candidate for the next generation of lithium-ion battery cathode materials due to its 4.1 V(vs. Li/Li+) high voltage platform. At present, the discharge rate performance and cycle stability are still poor. And here, various Fe, Ni co-doped carbon-coated LiMnPO4 composites materials LiMnPO4/C were successfully prepared using coprecipitation and solvothermal methods. Morphological and electrochemical performance analyses were conducted on the LiMnPO4/C materials prepared by different methods to explore the relationship between material morphology and electrochemical performance. Compared with the coprecipitation method, LiMnPO4/C prepared by the solvothermal method has a smaller particle size and a more regular morphology. Moreover, after the addition of glucose as an auxiliary, the particles exhibit a spindle-shaped porous structure, leading to improved cycling performance and rate capability, and demonstrating superior electrochemical properties. At 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1, and 2 C, the discharge specific capacities are 121.4, 102.7, 91.2, 81.5, and 53.7 mAh g− 1, respectively. After 100 cycles at 1 C rate, 91% of the initial capacity is still retained. The above results indicate selecting appropriate preparation methods and controlling the structure and morphology of the material, the electrochemical activity of LiMnPO4 can be directly influenced, which providing a new approach to improve the electrochemical performance of LiMnPO4.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the depletion of fossil resources and the increasing demand for energy, energy crises and environmental pollution have become two major global challenges1,2. Low-carbon, green, and efficient renewable energy has become a key focus of research and development3,4,5,6. Lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) are currently widely used in portable electronic devices, electric vehicles, and large-scale energy storage systems due to their high energy density, long cycle life, and environmentally friendly nature7,8,9,10. As a crucial component of LIBs, the cathode material determines the performance and price of LIBs11,12,13. Among them, olivine-type lithium transition metal phosphates (LiMPO4, M = Mn, Fe, Co, Ni) have been widely studied and applied as LIBs cathode materials in recent years14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21. This is due to the strong P-O covalent bonds and stable three-dimensional framework structure of PO43−, which prevents structural rearrangement during Li+ insertion/extraction, resulting in good structural stability.

Since its first synthesis and report by Goodenough’s research group in 1997, LiFePO4 has been widely used as a cathode material in lithium-ion batteries due to its advantages of good stability, environmental friendliness, and low cost22,23,24. Despite these advantages, lithium iron phosphate (LFP) is limited by its low theoretical capacity(170 mAh g− 1), in particular, the Fe2+/Fe3+ redox couple results in a relatively low discharge voltage plateau (3.4 V vs. Li/Li+) for LiFePO4, leading to a low theoretical energy density (578 Wh kg− 1) and severely hindering its application in power batteries25,26,27,28. In contrast, LiMnPO4 also possesses an olivine structure and exhibits a higher voltage plateau of 4.1 V (vs. Li/Li+), a theoretical capacity similar to LiFePO4 (170 mAh g− 1), and an energy density approximately 20% higher than LiFePO4. It also has advantages such as low toxicity, safety, and low cost, making it better suited to meet the high energy density requirements of next-generation lithium-ion batteries29,30,31. Notably, the operating potential of LiMnPO4 is compatible with the voltage window of most currently used lithium-ion battery electrolytes, making it an ideal alternative to LiFePO4 as a cathode material32,33. However, the extremely low electronic conductivity and Li+ migration rate of LiMnPO4 lead to poor rate performance, posing the biggest challenge to its development11. Furthermore, the Jahn-Teller effect of Mn3+ in the delithiated phase MnPO4 causes lattice distortion and excessive volume change during Li+ insertion/extraction, resulting in poor cycle stability of LiMnPO4 batteries. These factors hinder the commercial application of LiMnPO4 batteries and represent significant challenges for the development of LiMnPO4 cathode materials29,34.

Currently, strategies such as carbon coating, ion doping, and material nanostructuring are primarily employed to enhance the electrochemical performance of LiMnPO435,36,37. Among these, cation doping has become a common method for improving the electrochemical properties of LiMnPO4. For example, Khalfaouy et al.38. prepared Ni-doped LiMnPO4 material, LiMn1 − xNixPO4 (x = 0.00-0.05), and found that nickel doping significantly improved the cycle stability and rate performance of LiMnPO4. Li et al.39. synthesized Fe-doped LiMn0.8Fe0.2PO4/C composite material via a solid-state method using different iron sources. The results showed that iron doping could also significantly improve the rate performance and cycle performance of LiMnPO4. Simultaneously, optimizing the morphology to improve the transport properties of LiMnPO4 has also become a research focus. Morphology and particle size control are crucial for Li+ diffusion in LiMnPO4 and significantly affect its rate performance, representing an effective pathway to achieve high-performance of LiMnPO421,40,41,42. Among various preparation methods, the solvothermal method not only promotes a complete reaction of reactants but also allows for simpler control of crystal morphology by adjusting the supersaturation of the solution through temperature and pressure control. This method is widely used for the synthesis of LiMnPO4 materials with various morphologies43,44,45.

Currently, most studies employ single-element doping methods to improve the electrochemical performance of LiMnPO4, while research on double-element doping is relatively limited. Based on previous studies of nickel and iron doping, this work adopts a Fe, Ni double-doping strategy (molar ratio of Mn: Fe: Ni = 0.85:0.075:0.075) to synthesize three carbon-coated LiMnPO4/C composites using co-precipitation and solvothermal methods, respectively. The prepared LiMnPO4/C composites are then characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and galvanostatic charge-discharge tests. The influence of different synthesis methods on the morphology and electrochemical performance of Fe, Ni double-doped LiMnPO4/C was comparatively studied.

Materials and methods

Preparation of LiMnPO4 and LiMnPO4/C composites

Three Ni, Fe co-doped LiMnPO4/C composite materials were prepared using co-precipitation and solvothermal methods, respectively. The molar ratio of Mn: Fe: Ni is 0.85:0.075:0.075 in all cases. All reagents used in this work are analytical reagent (AR) grade. These include lithium hydroxide (LiOH·H2O, Tianjin Kemiou Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd.), phosphoric acid (H3PO4, Xilong Science), manganese sulfate (MnSO4·H2O, Xilong Science), ferrous sulfate (FeSO4·7H2O, Xilong Science), ethylene glycol (C2H6O2, Xilong Science), nickel nitrate (Ni(NO3)2·6H2O, Shanghai Reagent Second Factory), glucose (C6H12O6, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd.), sucrose (C12H22O11, Chengdu Jinshan Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd.), and cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) ((C16H33)N(CH3)3Br, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd.).

Co-precipitation method: First, 0.0425 mol MnSO4·H2O was dissolved in 30 ml deionized water, and 0.0425 mol H3PO4 was dissolved in 10 ml deionized water separately. The H3PO4 solution was added to the MnSO4·H2O solution and stirred for 1 h. Then 0.1275 mol LiOH·H2O and 0.075 g CTAB (0.1 wt%) were added to the above mixture under continuous stirring until a brown uniform solution is obtained, labelled solution A1. Second, 0.00375 mol FeSO4·7H2O and 0.00375 mol Ni(NO3)2·6H2O were dissolved in 15 ml deionized water under stirring, 0.0075 mol H3PO4 was dissolved in 5 ml deionized water additionally, and this H3PO4 solution was added dropwise to the mixed FeSO4· and Ni(NO3)2 solution and stirred at room temperature for 1 h. Then 0.0225 mol LiOH·H2O and 0.035 g CTAB were slowly added dropwise to the above solution and continue stirred at room temperature for 1 h, labelled solution A2. Third, solution A1 and solution A2 were mixed and stirred magnetically at 50 ℃ for 6 h. After standing overnight, the precipitate was separated by centrifugation. The precipitate was dried at 80 ℃ for 12 h in a drying oven to obtain a precursor. The precursor was mixed with a sucrose aqueous solution(precursor to sucrose mass ratio of 2:1) and stirred for 2 h. The mixture was then dried at 80 ℃ for 24 h in a drying oven. Finally, the mixture was sintered at 600 ℃ for 5 h under N2 atmosphere to obtain LiMnPO4/C, denoted as LiMnPO4/C-A.

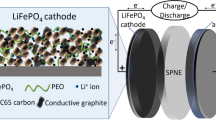

Solvothermal method: Based on the co-precipitation method described above, the difference is that the solvent is replaced with a mixture of glycol and water (volume ratio 1:1), the resulting B1 and B2 mixed solution was transferred to a hydrothermal autoclave and maintained at 180 ℃ for 10 h. After centrifugation and drying, the precursor was mixed with sucrose (precursor to sucrose mass ratio of 2:1) in an aqueous solution and stirred for 2 h as the precipitation method mentioned above. Then drying and calcination and mixing with sucrose like the precipitation method mentioned above and the resulting material was labeled LiMnPO4/C-B. Additionally, LiMnPO4/C was prepared using the same solvothermal method, the difference is that 1 gram of glucose was added during the hydrothermal process, and the resulting material was labeled LiMnPO4/C-C. The preparation process of LiMnPO4/C-C is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Material characterization

The phase structures of all synthesized samples were analyzed by X-ray diffraction (XRD, Shimadzu XRD-6100) using Cu Kα radiation in the 2θ range of 5–80°. The morphologies of the synthesized samples were characterized using field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM, Hitachi SU8010). The elemental distribution of the LiMnPO4/C-C sample was analyzed by energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS, Horiba EMAX). The specific surface area and pore size distribution of the samples were characterized by nitrogen adsorption/desorption isotherms at 77 K obtained using a surface area and porosity analyzer (Micromeritics ASAP2460).

Electrochemical tests

The active material, acetylene black, and polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) were mixed in a weight ratio of 80:10:10, respectively (the active material loading is 1.5 mg). The mixture was homogenized by stirring in N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP) for 6 h to form a slurry. This slurry was then uniformly coated onto an aluminum foil current collector using a coating machine (Shenzhen Kejing MSK-AFAE-S200). The resulting electrode was dried overnight at 80 °C. The electrode was transferred to an argon-filled glove box (Vigor SG1200/750TS) and used as the positive electrode in a CR2025 coin cell. A Celgard 2400 membrane served as the separator, lithium foil as the negative electrode, and 1 M LiPF6 solution in ethylene carbonate (EC): diethyl carbonate (DEC): dimethyl carbonate (DMC) (volume ratio 1:1:1) as the electrolyte.

Constant current charge-discharge tests were performed using a Land CT3002A battery tester within a voltage range of 2.5–4.5 V. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements were conducted on a Princeton Applied Research VersaSTAT 3 electrochemical workstation over a frequency range of 10− 2 to 105 Hz. All tests were performed at 25 °C.

Results and discussion

XRD and SEM analysis

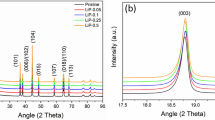

Figure 2 shows the XRD patterns of the three prepared samples: LiMnPO₄/C-A, LiMnPO₄/C-B, and LiMnPO₄/C-C. All three samples show good agreement with the LiMnPO₄ standard PDF# 33–0803, this indicates that LiMnPO₄/C were prepared successsfully. The absence of carbon diffraction peaks may be attributed to the amorphous nature of the carbon36. On the other hand, the lack of iron and nickel peaks may be due to their low concentrations being masked by the manganese signal, there is a number marked as nickel peak. All XRD peaks match those of LiMnPO₄, with no additional peaks present, indicating that nickel-iron doping has been incorporated into the LiMnPO₄ crystal lattice.

The morphologies of the three samples, LiMnPO4/C-A, LiMnPO₄/C-B, and LiMnPO₄/C-C, are shown in Fig. 3. The co-precipitation method produced LiMnPO₄/C-A with an irregular morphology and large particle size, exhibiting non-nanoscale agglomeration. The solvothermal method yielded LiMnPO₄/C-B with a more regular rod-like morphology, approximately 100 nm in width and 200–300 nm in length. The glucose-assisted solvothermal method produced LiMnPO₄/C-C with a regular, spindle-shaped, porous structure. The particle size of LiMnPO₄/C-C is similar to LiMnPO₄/C-B, but with a more uniform distribution. Further TEM characterization revealed the porous structure of LiMnPO₄/C-C, Fig. 5 clearly shows the distinct porous structure of LiMnPO₄/C-C, in contrast to LiMnPO₄/C-A and LiMnPO₄/C-B which lack porosity. The uniformly small particles are beneficial for shortening the Li⁺ diffusion pathways, while the porous structure facilitates increased contact with the electrolyte33,46.

To further determine the elemental composition and distribution of the LiMnPO₄/C-C nanomaterial, energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) and elemental mapping were performed on the prepared LiMnPO₄/C-C material, with the results shown in Fig. 4. Figure 4 shows that Fe, Ni, and C elements are uniformly distributed throughout the LiMnPO₄/C-C sample, indicating successful doping of Fe and Ni into the LiMnPO₄ material.

To further characterize the porous structure of the synthesized LiMnPO₄/C-C, nitrogen adsorption-desorption tests were performed on the prepared LiMnPO₄/C-C, and the results are shown in Fig. 6. The BET surface area of LiMnPO₄/C-C is 63.0 m²g− 1, and the pore volume is 0.12 cm³g− 1. The adsorption-desorption isotherm (Fig. 6a) is a typical type IV isotherm, exhibiting a clear hysteresis loop at higher nitrogen pressure, indicating a mesoporous structure of LiMnPO₄/C-C47. Figure 6b shows that the LiMnPO₄/C-C has an unimodal pore-size distribution with a average pore diameter of 7.46 nm. The large surface area provides more active sites for Li⁺ insertion/extraction, and the nanoporous structure contributes to an improved Li⁺ diffusion rate.

Figure 7 presents the XPS analysis of LiMnPO4/C-A, LiMnPO₄/C-B, and LiMnPO₄/C-C. The survey scan reveals the presence of nickel (Ni) and iron (Fe) elements. Furthermore, the Mn 2p peak is consistent with that reported in the literature for Fe-doped LiMnPO₄, while the Fe2p peak (Fe2p3/2:710.73, 711.05, 709.56 eV, Fe2p1/2:723.76, 724.34, 724.16 eV), matches that reported for LiMn₀.₉Fe₀.₁PO₄48. Based on the preceding XRD and elemental mapping analyses, it can be concluded that nickel- and iron-doped LiMnPO₄ has been successfully synthesized.

Electrochemical performance of LiMnPO4/C composites

Figures 8 and 9 show the charge-discharge curves and rate performance of LiMnPO4/C-A, LiMnPO4/C-B, and LiMnPO4/C-C, respectively. Figure 8 reveals that all three materials exhibit a discharge plateau around 4.1 V, consistent with most literature reports on LiMnPO4, further confirming the successful synthesis of LiMnPO4. At 0.1 C, the co-precipitation method prepared LiMnPO4/C-A shows a maximum discharge capacity of 45.9 mAh g⁻¹, the solvothermal method prepared LiMnPO4/C-B exhibits a maximum discharge capacity of 117.9 mAh g⁻¹, and the glucose-assisted solvothermal method prepared LiMnPO4/C-C shows a maximum discharge capacity of 121.4 mAh g⁻¹. Clearly, the solvothermal methods significantly improve the maximum discharge capacity of LiMnPO4/C. Figure 9 shows that the discharge capacities of LiMnPO4/C-A, LiMnPO4/C-B, and LiMnPO4/C-C are 2 mAh g⁻¹, 4.7 mAh g⁻¹, and 53.7 mAh g⁻¹ at 2 C, respectively. LiMnPO4/C-C demonstrates superior rate performance, indicating that glucose significantly enhances the rate capability of the LiMnPO4/C material.

Figure 10 presents the discharge cycling performance of LiMnPO4/C-B and LiMnPO4/C-C at 1 C for 100 cycles. LiMnPO4/C-B exhibits a capacity retention of 80.7%, while LiMnPO4/C-C shows a significantly improved capacity retention of 91.0%. This indicates that the LiMnPO4/C-C material, with its regular, nanostructured, spindle-like morphology, possesses superior cycling stability. Combining this with the previous morphological and structural analysis, it is found that the LiMnPO4/C-C material, with its regular, nanostructured, spindle-like porous structure, not only shows significant improvements in discharge capacity and rate performance but also exhibits greatly enhanced discharge cycling stability. Table 1 compares the electrochemical performance of this material with that of LiMnPO4 materials reported in recent literature.

Figure 11 shows the Nyquist plots and equivalent circuit diagrams for LiMnPO4/C-A, LiMnPO4/C-B, and LiMnPO4/C-C electrodes. The inset table presents the fitting data of the EIS curves. The curves consist of a semicircle in the high-frequency region and a sloping line in the low-frequency region. The diameter of the semicircle corresponds to the charge transfer resistance (Rct) between the electrode and the electrolyte, while the intercept of the semicircle on the Z’ axis is attributed to the solution resistance (Rs). The slope of the inclined line (Zw) represents the Warburg impedance, corresponding to the diffusion of Li+ ions in the bulk material22,34,53. The Rct values for LiMnPO4/C-A, LiMnPO4/C-B, and LiMnPO4/C-C electrodes are 204.1, 76.8, and 64.9 Ω, respectively, indicating that LiMnPO4/C-C exhibits a faster electrochemical response and better kinetic performance. Furthermore, the slope of the inclined line in the low-frequency region is steeper for the LiMnPO4/C-C electrode than for LiMnPO4/C-A and LiMnPO4/C-B, indicating a smaller Zw and a faster Li+ diffusion rate. The EIS results demonstrate that LiMnPO4/C-C possesses superior electrochemical kinetics, further validating the interpretations of the previous charge-discharge and cycling performance test results.

Conclusions

A variety of Fe and Ni doping LiMnPO4 composites were prepared through three different methods : LiMnPO4/C-A, LiMnPO4/C-B, and LiMnPO4/C-C. Comparative analysis reveals that the LiMnPO4/C-C material prepared by a glucose-assisted solvothermal method exhibits smaller particle size and a more regular morphology compared to the co-precipitation method, and the material displays a spindle-shaped porous structure. Benefiting from this nanosize, regular morphology and porous structure, the battery prepared using this material shows significantly improved rate performance and cycling performance, demonstrating superior electrochemical properties. Their discharge capacities are achieved of 121.4, 102.7, 91.2, 81.5, and 53.7 mAh g⁻¹ at 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1, and 2 C rates, respectively, and the capacity retention reaches 91% after 100 charge-discharge cycles at 1 C. This demonstrates that selecting an appropriate preparation method and controlling the morphology and structure of the material are crucial for optimizing the electrochemical performance of LiMnPO4. This study provides a basis and guidance for further optimization of the electrochemical performance of LiMnPO4 materials.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper, and the data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Wu, F., Maier, J. & Yu, Y. Guidelines and trends for next-generation rechargeable lithium and lithium-ion batteries. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49 (5), 1569–1614 (2020).

Iqbal, M. Z., Abbasi, U. & Alzaid, M. Cobalt manganese phosphate and sulfide electrode materials for potential applications of battery-supercapacitor hybrid devices. J Energy Storage, 50 104632.1-104632.11.(2022)

Xue, Z. et al. Sodium doping to enhance electrochemical performance of overlithiated oxide cathode materials for Li-Ion batteries via li/na Ion-exchange method. ACS Appl. Interfaces. 10 (32), 27141–27149 (2018).

Wu, L. et al. PPy-encapsulated SnS2 nanosheets stabilized by defects on a TiO2 support as a durable anode material for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. 58 (3), 811–815 (2018).

Chen, W. et al. Mn-doped LiFePO4@C as a high-performance cathode material for lithium-ion batteries. Particuology 90, 418–428 (2024).

Wang, G. et al. Chemically activated Hollow carbon nanospheres as a high-performance anode material for potassium ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A. 6 (47), 24317–24323 (2018).

Zhang, T. W. et al. Recent advances on biopolymer fiber based membranes for lithium-ion battery separators. Compos. Commun. 14, 7–14 (2019).

Ragupathi, V., Panigrahi, P. & Nagarajan, G. S. Enhanced electrochemical performance of nanopyramid-like LiMnPO4/C cathode for lithium-ion batteries. Appl Surf. Sci, 495(30): (2019). 143541.1-143541.6.

Pender, J. P. et al. Electrode degradation in lithium-Ion batteries. ACS Nano. 14 (2), 1243–1295 (2020).

Gu, K. et al. Efficient separation of cathode materials and al foils from spent lithium batteries with glycerol heating: A green and unconventional way[J]. J Clean. Prod, 369(1)133270.1-133270.9.(2022)

Yang, L. et al. Olivine LiMnxFe1–xPO4 cathode materials for lithium ion batteries: restricted factors of rate performances. J. Mater. Chem. A. 9 (25), 14214–14232 (2021).

Yang, J. et al. Green synthesis of high-performance LiFePO4 nanocrystals in pure water. Green. Chem. 20 (22), 5215–5223 (2018).

Deng, Z. et al. Fast precipitation-induced LiFe0.5Mn0.5PO4/C nanorods with a fine size and large exposure of the (010) faces for high-performance lithium-ion batteries. J. Alloy Compd. 794, 178–185 (2019).

Zou, B. et al. Solvothermal synthesized LiMn1 – xFexPO4@C nanopowders with excellent high rate and low temperature performances for lithium-ion batteries. RSC Adv. 6 (57), 52271–52278 (2016).

Chen, W. et al. Rational design of nano-structured ammonium manganese phosphate hydrate as lithium ion battery anode. Mater Lett, 285(15): 129084.1-129084.5. (2021).

Jung, Y. H. et al. A multi-element doping design for a high-performance LiMnPO4 cathode via metaheuristic computation. J. Mater. Chem. A. 5 (19), 8939–8945 (2017).

Zeng, T. et al. LiMn0.8Fe0.2PO4@C cathode prepared via a novel hydrated MnHPO4 intermediate for high performance lithium-ion batteries. Inorg. Chem. Front. 10 (4), 1164–1175 (2023).

Nag, S. & Roy, S. La-doped LiMnPO4/C cathode material for Lithium-ion battery. Chem Eng. Sci, 272: (2023). 118600.1-118600.6.

Chen, J. et al. High performance of LiMn1 – xFexPO4/C (0 ≤ x ≤ 0.5) nanoparticles synthesized by microwave-assisted solvothermal method. Ionics 24 (3), 689–696 (2017).

Xiang, W. et al. Hierarchical structured LiMn0.5Fe0.5PO4 spheres synthesized by template-engaged reaction as cathodes for high power Li-ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta. 178, 353–360 (2015).

Peng, Z. et al. Green and efficient synthesis of micro-nano LiMn0.8Fe0.2PO4/C composite with high-rate performance for Li-ion battery. Electrochim Acta, 387: 138456.1-138456.10. (2021).

Padhi, A. K., Nanjundaswamy, K. S. & Goodenough, J. B. Phospho-olivines as positive-electrode materials for rechargeable Lithium batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 144 (4), 1188–1194 (1997).

Wang, J. & Sun, X. Olivine LiFePO4: the remaining challenges for future energy storage. Energ. Environ. Sci. 8 (4), 1110–1138 (2015).

Layadi, T. M. et al. Design of sustainable multi-source power systems using lithium batteries. J Energy Storage, 60(3): 106648.1-106648.14. (2023).

Huang, Y. et al. Integrated rocksalt–polyanion cathodes with excess lithium and stabilized cycling. Nat. Energy. 9 (12), 1497–1505 (2024).

Yang, J. et al. Zero Lithium miscibility gap enables High-Rate equimolar Li(Mn,Fe)PO4 solid Solution. Nano Lett. 21 (12), 5091–5097 (2021).

Oukahou, S. et al. Investigation of LiMn1 – xMxPO4 (M = Ni, Fe) as cathode materials for Li-ion batteries using density functional theory. Comp Mater. Sci, 202: (2022). 111006.1-111006.11.

Pleuksachat, S. et al. Dynamic phase transition behavior of a LiMn0.5Fe0.5PO4 olivine cathode material for lithium-ion batteries revealed through in-situ X-ray techniques. J. Energy Chem. 71, 452–459 (2022).

Zhu, J. N. et al. Synthesis of LiMnPO4/C with superior performance as Li-ion battery cathodes by a two-stage microwave solvothermal process. J. Mater. Chem. A. 3 (26), 13920–13925 (2015).

Li, S. N. et al. Synthesis and electrochemical properties of LiFePO4 cathode material by ionic thermal method using eutectic mixture of tetramethyl ammonium chloride-urea. Rare Met. 40 (12), 3477–3484 (2021).

Sharmila, V. & Parthibavarman, M. Lithium manganese phosphate associated with MWCNT: Enhanced positive electrode for lithium hybrid batteries. J Alloy Compd, 858: 157715.1-157715.10. (2021).

Zhang, J. N. et al. Trace doping of multiple elements enables stable battery cycling of LiCoO2 at 4.6 V. Nat. Energy. 4 (7), 594–603 (2019).

Lu, X. et al. Ethylene glycol solvothermal synthesis of LiMnPO4 nanoparticles with high (2 0 0) crystal face exposure for high performance lithium-ion batteries. Mat Sci. Eng. B, 299: (2024). 117032.1-117032.7.

Wen, F. et al. Graphene-embedded LiMn0.8Fe0.2PO4 composites with promoted electrochemical performance for lithium ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta. 276, 134–141 (2018).

Pan, X. et al. Self-templating Preparation and electrochemical performance of LiMnPO4 Hollow microspheres. J. Alloy Compd. 783, 468–477 (2019).

Chi, Z. X. et al. Accurate surface control of core-shell structured LiMn0.5Fe0.5PO4@C for improved battery performance. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2 (41), 17359–17365 (2014).

Zhang, B. et al. [001]-oriented LiMn0.6Fe0.4PO4/C Nanorod microspheres contributing high-rate performance to olivine-structured cathode for lithium-ion battery. Mater Today Energy, 30: (2022). 101162.1-101162.12.

El, K. R. et al. Nickel-substituted LiMnPO4/C olivine cathode material: combustion synthesis, characterization and electrochemical performances. Ceram. Int. 45 (14), 17688–17695 (2019).

Li, Y. et al. Simple synthesis of a hierarchical LiMn0.8Fe0.2PO4/C cathode by investigation of iron sources for lithium-ion batteries. RSC Adv. 12 (40), 26070–26077 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. Rational design of a synthetic strategy, carburizing approach and pore-forming pattern to unlock the cycle reversibility and rate capability of micro-agglomerated LiMn0.8Fe0.2PO4 cathode materials. J. Mater. Chem. A. 6 (22), 10395–10403 (2018).

Shi, S. et al. Multi-scale computation methods: Their applications in lithium-ion battery research and development. Chinese Physics B, 25 (1) 018212.1-018212.24. (2016).

Hong, Y. et al. High-yield synthesis of LiMnPO4/C nanoplates as cathode materials for lithium-ion batteries. Scripta Mater, 241 (2024). 115878.1-115878.7.

Zhu, C. et al. Solvothermal-assisted morphology evolution of nanostructured LiMnPO4 as high-performance lithium-ion batteries cathode. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 34 (9), 1544–1549 (2018).

Hong, Y. et al. High-performance LiMnPO4 nanorods synthesized via a facile EG-assisted solvothermal approach. J. Mater. Chem. A. 3 (19), 10267–10274 (2015).

Liao, L. et al. Facile solvothermal synthesis of ultrathin LiFexMn1–xPO4 nanoplates as advanced cathodes with long cycle life and superior rate capability. J. Mater. Chem. A. 3 (38), 19368–19375 (2015).

Niu, Y. H. et al. Controllable synthesis of aluminium-doped LiMnPO4/C cathode materials with stable electrochemical performance for lithium-ion battery. Mat Sci. Eng. B, 299(1) 117009.1-117009.8. (2024).

Wang. L. et al. Improved electrochemical performance and capacity fading mechanism of nano-sized LiMn0.9Fe0.1PO4 cathode modified by polyacene coating[J]. J. Mater. Chem. A. 3(4), 1569–1579 (2015).

Li J, et al. Facile synthesis of carbon-LiMnPO4 nanorods with hierarchical architecture as a cathode for high-performance Li-ion batteries[J]. Electrochim Acta, 289, 415–421 (2018).

Nwachukwu, I. M. et al. The potentials of LiMnPO4 cathode material for aqueous Li-ion batteries: an investigation into solid state and green chemistry approaches. Appl Surf. Sci. Adv, 19, 100537.1-100537.12 (2024).

Manjunatha, H., Venkatesha, T. V. & Suresh, G. S. Electrochemical studies of LiMnPO4 as aqueous rechargeable lithium-ion battery electrode. J. Solid State Electr. 16 (5), 1941–1952 (2011).

Zhang, L. et al. Confined synthesis of hierarchical structured LiMnPO4/C granules by a facile surfactant-assisted solid-state method for high-performance lithium-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2 (3), 711–719 (2014).

Vásquez, F. A. & Calderón, J. A. Vanadium doping of LiMnPO4 cathode material: Correlation between changes in the material lattice and the enhancement of the electrochemical performance. Electrochim Acta, 325: 134930.1-134930.10. (2019).

Muruganantham, R., Sivakumar, M. & Subadevi, R. Polyol technique synthesis of Nb2O5 coated on LiFePO4 cathode materials for Li-ion storage. Ionics 24 (4), 989–999 (2017).

Funding

This work was supported by the funding program of “Carbon Neutral Engineering Research Center of Guizhou colleges and universities in Coal Industry (Qian Jiao Ji [2023] No. 044)”, “Guizhou Provincial Science and Technology Projects (Qiankehejichu-ZK [2022] Yiban531) and “the High-level Talents Scientific Research Startup Foundation of Liupanshui Normal University (Grant No. LPSSYKYJJ202006).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, validation, L.J-L; writing-original draft, L Z-B and M J-r; review and editing, L J-L; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, J., Liu, Z. & Ma, J. Preparation and improvement electrochemical performance of Ni-Fe doped porous LiMnPO4/C materials. Sci Rep 15, 28004 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12971-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12971-y