Abstract

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is commonly considered to improve physical function in patients with knee osteoarthritis (OA). However, factors related to pre- and postoperative physical performance remain unclear. Therefore, this prospective cohort study aimed to evaluate the association between the phase angle (PhA) determined via bioelectrical impedance and physical status in patients with knee OA awaiting TKA. In total, 226 patients (age 72.6 years; 35 males; 112 bilateral symptoms) were divided into low and high PhA groups; between-group differences and changes over time were analyzed. The low PhA group (n = 62) had significantly lower muscle strength and physical performance than did the high PhA group (n = 164). Of the cohort, 63 (27.9%) patients completed the 3-month postoperative assessment. While physical performance significantly improved in both groups, the low PhA group still exhibited poorer physical performance (P < .005). Multivariable analysis identified a low PhA as an independent risk factor for the 10-meter walk (β = -0.215; 95% confidence interval [CI]: -0.291 to -0.140) and log-transformed timed up-and-go test performance (β = 0.218; 95% CI 0.140 to 0.296) after adjusting for baseline covariates. A low PhA could indicate poor pre- and postoperative physical status in patients with knee OA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Knee osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common form of osteoarthritis1. The age-standardized prevalence of knee OA is 4,307 cases per 100,000 individuals, and the number of patients with knee OA is expected to increase by approximately 75% by 20501. As knee OA progresses, patients experience joint pain and stiffness, leading to physical inactivity and disability2,3. Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is an effective treatment for patients with knee OA in whom nonsurgical treatments fail to improve physical function, joint pain, and quality of life4,5. With the increasing number of TKA surgeries performed, there is a growing interest in the factors influencing postoperative outcomes.

Despite advances in surgical techniques5 the factors influencing functional recovery after TKA remain unclear. Notably, more than 20% of patients who underwent TKA were dissatisfied with the outcome, and this satisfaction did not align with performance-based outcomes or quadriceps muscle strength6,7. A recent meta-analysis revealed a positive correlation between preoperative and postoperative function8 contradicting the results of a previous systematic review reporting that low preoperative physical function is a prognostic factor for superior postoperative physical function9. Obesity is a well-known risk factor for poor outcomes4,8; however, its impact on TKA outcomes was too small to achieve clinical significance10. These conflicting findings highlight the need for further research on the factors that influence postoperative physical function following TKA.

Emerging evidence suggests that muscle quality rather than muscle mass may be a key determinant of physical function in patients with knee OA11,12. A higher ratio of intramuscular fat to lean mass in the quadriceps, quantified using magnetic resonance imaging, is associated with higher pain intensity and poorer physical function11. Furthermore, increased echogenicity in the thigh muscles, which denotes higher intramuscular adipose tissue levels, as measured via ultrasonography, is associated with reduced mobility performance, whereas muscle thickness is unrelated to functional outcomes12. However, measurements using imaging modalities require large-scale equipment, long restraint hours, and expertise; thus, simpler and more objective indices of body composition have been investigated.

Bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) is an inexpensive and portable method used to estimate body composition by passing a weak current through the body. In particular, the phase angle (PhA) is gaining attention because it is directly calculated from the reactance and resistance to varied frequencies, whereas other parameters, such as muscle mass, are estimated based on a prediction formula13. The PhA has been considered as an index reflecting the physiological function of cell membranes and an indicator of muscle quality14. A higher PhA is associated with increased quadriceps strength independent of lower limb muscle mass15. Moreover, the PhA is independently related to gait function and the ground reaction force index during standing, whereas muscle mass does not correlate with any motor function-related measurements16. However, previous studies have not explored the relationship between the PhA and postoperative physical function15,16.

To this end, our study aimed to investigate the differences in pre- and postoperative physical status according to the PhA in patients with knee OA scheduled for TKA. This was addressed through two objectives: First, to compare clinical characteristics—such as radiological severity of knee OA, quadriceps muscle strength and mass, and physical function—between the low and high PhA groups; second, to examine whether a low PhA is independently associated with physical performance 3 months after TKA.

Methods

Participants and sample size

A prospective cohort study was conducted at a single medical center in the Republic of Korea. Individuals with knee OA who were scheduled for TKA between March 2021 and August 2024 were initially included. Knee OA was confirmed based on medical history, physical examination, and radiographic assessment of the knee joints17. The exclusion criteria were as follows: patients (1) aged < 55 years; (2) with neurological disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease, stroke, and dementia; (3) with severe cardiac, pulmonary, or musculoskeletal disorders limiting physical function; (4) with knee OA due to secondary causes; and (5) with a history of any knee surgery within 1 year. Patients with missing values of preoperative variables were excluded from the relevant analyses. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Yonsei University (9-2024-0150); performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations, including the Declaration of Helsinki; and reported according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines18. Informed consent was obtained from all patients before enrollment.

The required sample size to achieve 80% power at a two-sided α-level of 0.05 using an independent two-sample t-test was calculated using G*Power version 3.1.9.6 (Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany)19. The target effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.88) was derived from a previous study that reported a 0.15 m/s difference in gait speed between patients with OA with and without sarcopenia (pooled standard deviation = 0.17)20. This value is more conservative than that of another study reporting a higher effect size (Cohen’s d = 1.02) for the correlation between the PhA and walking speed21. With an expected recruitment ratio of 1:2, the minimum total sample size required was 48 participants (low PhA: n = 16, high PhA: n = 32). Patients were continuously enrolled until at least 48 participants had completed the 3-month postoperative follow-up.

Baseline characteristics

Baseline data on demographics, comorbidities, and clinical covariates were collected. Physical activity levels were assessed using the validated the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)22. The burden of comorbidities was calculated using a modified version of the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI). A numeric pain rating scale was used to assess participants’ initial pain levels.

Handgrip strength was measured using a JAMAR Plus dynamometer (Health International LTD, Ashfield, UK), according to the standardized protocol23. Low handgrip strength was defined as a grip strength < 28 kg for males and < 18 kg for females23.

Passive knee flexion/extension angles were measured using a goniometer. All radiographs were evaluated preoperatively by an experienced, board-certified physiatrist (Y.S.K). Hip–knee–ankle, lateral distal femoral, medial proximal tibial, and joint line convergence angles were manually measured on radiographs in the standing position24. The radiographic severity of knee OA was assessed using the Kellgren–Lawrence grading system.

Physical function and isokinetic strength

Physical function was evaluated using the 10-meter walk test (10MWT), timed up-and-go test (TUGT) and Berg Balance Scale (BBS). For the 10MWT, patients were instructed to walk 14 m, including 2 m at both ends for acceleration and deceleration, at a comfortable speed25. Gait speed was calculated by dividing the 10-m distance by the time taken. For the TUGT, patients stood up from a seated position, walked 3 m, turned around, returned to the chair, and sat down26. This was repeated three times, and the average time was recorded for analysis. Static and dynamic balance were measured with the BBS, which consists of 14 tasks rated from 0 to 4, producing a total score of 0–5627.

Peak torque and total work during knee extension and flexion were assessed using an isokinetic dynamometer (Cybex NORM®, Humac, Stoughton, MA). Participants were instructed on the standardized procedures before and during the test28. Concentric measurements were performed at angular velocities of 60°/s and 150°/s, with a rest period between trials. The trials were repeated three times, and the average values were recorded for analysis.

PhA and body composition

BIA was performed with InBody S10 (BioSpace, Seoul, South Korea), which has shown high concordance with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry—the gold-standard method—and acceptable inter-device reliability29,30. Before measurement, all patients were instructed to fast for a minimum of 3 h, avoid alcohol and vigorous activity, and empty the bladder. Patients assumed a supine position, and eight electrodes were attached to their wrists and ankles. After resting for 15 min, body composition was estimated from the reactance and impedance of different frequencies. The PhA was calculated as the arctangent of the reactance-to-resistance ratio at 50 kHz13. Low muscle mass, calculated by height2 − adjusted appendicular skeletal muscle mass, was defined as < 7.0 kg/m2 for males and < 5.7 kg/m2 for females23. The cutoff point for a low PhA was set as 4.95 for males and 4.35 for females, as suggested by a previous study predicting physical disability in older adults31. The study population had a similar age distribution (71.8 ± 5.3 years) to that of our cohort (72.6 ± 6.6 years) and the same ethnic background.

Surgical techniques

Two board-certified orthopedic surgeons (K.C. and J.Y.P.), each with more than 5 years of clinical experience in the field, performed all TKAs. Either a medial parapatellar arthrotomy or mid-vastus approach with a mid-line skin incision was employed. Standard extramedullary and intramedullary instrumentation or navigated surgical instruments were used to achieve mechanical alignment. The postoperative protocol was identical for both groups and included education on postoperative exercises, such as range of motion exercises, quadriceps exercises, ankle pumps, and straight leg raises.

Postoperative assessment

Hip–knee–ankle, mechanical lateral–distal femoral, and medial–proximal tibial angles were calculated to evaluate the postoperative alignment of the lower limb32 with target values of 180°, 90°, and 90°, respectively. Any deviations greater than 3° were deemed outliers32. All performance-based and isokinetic strength tests were conducted 3 months after surgery using the same protocols described above.

Statistical analysis

The Shapiro–Wilk test was performed to assess the data distribution in all analyses. The baseline characteristics of the low and high PhA groups were compared using unpaired t-tests or the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables, whereas Fisher’s exact test or the chi-square test was applied for categorical variables. A pre–post comparison within each group was performed using paired t-tests or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test according to the data distribution. We performed multivariable linear regression to examine the association between a low PhA and postoperative physical function after adjusting for the following covariates: (1) preoperative variables significantly associated with the outcome (P < .05) and (2) variables deemed relevant in previous studies, including the body mass index (BMI), pain score, radiographic severity, and low handgrip strength4,8. After reviewing the assumptions, total work measurements were excluded from the multivariable analysis to avoid multicollinearity. TUGT results were log-transformed. The relationship of functional outcomes with BBS scores was not analyzed because the BBS scores did not meet the normality assumptions even after log-transformation. A stepwise backward regression was used to select significant variables for the final model. Goodness-of-fit was evaluated using the Hosmer–Lemeshow test, and multicollinearity was assessed using variable inflation factors. Cohen’s d effect sizes were calculated for between-group differences in pre- and postoperative physical function. For multivariable regression analyses, the magnitude of the PhA group effect was expressed using standardized regression coefficients and the percentage of variance explained by the variable.

All analyses were performed using R software version 4.2.3 (Boston, MA), and a two-tailed P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Comparison of baseline characteristics and physical function based on the pha

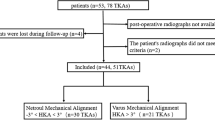

The flow of study participants is shown in Fig. 1. A total of 226 patients were included in the study (mean age, 72.6 ± 6.6 years; 35 [15.5%] male; 112 [49.6%] exhibited bilateral symptoms). Participants were classified into low (n = 62, 27.4%) or high PhA groups (n = 164, 72.6%). Participants in the low PhA group were significantly older and had lower handgrip strength than did those in the high PhA group, independent of unilateral or bilateral symptoms (P < .05, Table 1). A significantly lower skeletal muscle index was found in the low PhA group among patients with bilateral symptoms, whereas there was no significant between-group difference in the skeletal muscle index among participants with unilateral symptoms. There were no significant differences in sex, BMI, CCI, or the IPAQ scores between the low and high PhA groups, regardless of unilateral or bilateral symptoms. In the radiographic evaluation, significantly more patients in the low PhA group showed a high Kellgren–Lawrence grade (grade 3 or 4) in the asymptomatic knee (12 of 25 cases vs. 14 of 89 cases, P < .05), as well as a larger joint line convergence angle (P < .05) than that of patients in the high PhA group. There was no significant difference in the Kellgren–Lawrence grade of each knee between the groups among patients with bilateral symptoms.

The low PhA group demonstrated significantly slower gait speed and poorer TUGT and BBS scores than did the high PhA group, regardless of unilateral or bilateral symptoms (Table 2, P < .001, Cohen’s d > 0.8 for all three assessments). The low PhA group consistently demonstrated lower peak torque and total work during knee extension and flexion at both 60º/s and 150º/s across both legs, regardless of whether OA symptoms were present.

Changes in physical status after TKA

After the baseline assessment, all patients underwent TKA, and 63 of the 226 (27.9%) patients completed the follow-up assessment at 3 months (Table 3). The distribution of unilateral and bilateral TKAs between the low and high PhA groups showed no statistically significant difference (Χ2 = 2.685, df = 1, P = .10, Supplementary Table S1). There was no significant difference between the low (n = 20) and high PhA groups (n = 43) in radiographic alignment after surgery (Supplementary Table S2). Both groups exhibited significant improvements in the 10MWT, TUGT, BBS, and pain scores (P < .05), with no significant between-group difference in the magnitude of improvement (all P > .05, data not shown). However, the low PhA group continued to exhibit poorer performance than that of the high PhA group after surgery, with significantly slower 10MWT and TUGT times and lower BBS scores (P < .005, Cohen’s d > 1 for all three assessments). None of the isokinetic strength profiles showed significant changes after TKA in either group.

Association between physical function and the pha

Table 4 shows the univariable and multivariable regression analyses for the postoperative 10MWT and log-transformed TUGT results. Several factors were significantly associated with the 10MWT performance in univariable analysis, including a low PhA, baseline 10MWT result, age, peak extension and flexion torque, low handgrip strength, and CCI. These variables were also significantly associated with the log-transformed TUGT time, with male sex and baseline pain scores identified as significant predictors. A low PhA remained an independent risk factor for both 10MWT (β = -0.215; 95% confidence interval [CI]: -0.291 to -0.140, P = .020) and log-transformed TUGT results (β = 0.218; 95% CI: 0.140 to 0.296, P = .013) in the final multivariable regression models. A low PhA explained 5.89% of the variance for the 10MWT performance and 6.56% for the log-transformed TUGT results. In addition to a low PhA, baseline 10MWT results, log-transformed TUGT results, peak flexion torque on the asymptomatic side, and CCI remained significant predictors of functional outcomes (P < .05). BMI was an additional significant predictor of the log-transformed TUGT results (P < .05). All variable inflation factors in the final model were < 3.

Discussion

Our study highlights that the PhA is significantly related to preoperative and postoperative physical function in patients with knee OA undergoing TKA. The low PhA group exhibited reduced preoperative muscle strength and physical function compared with that of the high PhA group. Although TKA improved physical performance in both groups, the low PhA group continued to show inferior outcomes. A low PhA was also independently associated with poorer postoperative physical performance after adjusting for baseline covariates.

In the present study, patients with a low PhA consistently showed low strength in multiple muscle groups, including the handgrip muscles, quadriceps, and hamstrings. Although the underlying mechanism has not been fully elucidated, PhA values have been independently associated with handgrip strength in different age groups and among individuals with different health conditions33. Studies using muscle ultrasonography have shown a correlation between the PhA and echogenicity of the quadriceps muscle34,35; increased echogenicity reflects increased intramuscular fat and fibrous tissue levels, which are considered to decrease muscle quality11. Cellular and molecular changes in the quadriceps muscle, such as excessive extracellular matrix, fewer satellite cells, and greater collagen content, could contribute to a low PhA36. We report similar findings herein and also indicate involvement of the hamstring muscle.

In the present study, the low PhA group showed poorer preoperative physical performance than that of the high PhA group, independent of the measurement scale applied. This may be explained by the reduced strength of the lower extremity muscles as described above. Alternatively, a low PhA might imply deterioration of biological factors related to knee joint function. Local inflammation, such as synovitis and effusion, is prevalent in knee OA37. Pre-radiographic lesions, such as matrix changes in the cartilage, synovitis, bone marrow lesions, and degenerative changes in soft-tissue structures, including ligaments and the knee meniscus, have been detected in the early phase of the disease38. These changes are followed by alterations in membrane permeability and the amounts of extracellular and intracellular fluids, which could alter the determinants of the PhA14. Furthermore, a significant relationship has been shown between an increasing radiographic knee OA severity and a decreasing PhA15. Likewise, in the current study, patients in the low PhA group with unilateral symptoms had more severe radiographic OA on the asymptomatic side, whereas those with bilateral symptoms experienced more muscle loss. A low PhA in patients with knee OA may, therefore, indicate disease progression, related conditions, or both.

Physical performance improved after TKA in the low PhA group, albeit it remained significantly lower than that in the high PhA group before surgery. Considering that the knee extensor/flexor muscle strength did not significantly change in either group after surgery, the amelioration of other factors, including knee pain and stability, might have contributed to the functional improvement. In the low PhA group, pre- and postoperative gait speed and the TUGT results were not only lower than those in the high PhA group but also below the cutoff values for predicting poor prognosis (gait speed < 1.0 m/s23 and TUGT > 12 s39. Slow gait speed is used as an indicator of frailty, characterized by subclinical impairments in multiple organ systems that impede the body’s ability to maintain physiological homeostasis in the presence of stressors40. Although further studies are needed to determine whether patients with a low PhA have slower recovery or limited final function, our findings suggest that these patients have increased vulnerability for at least 3 months after surgery.

A low PhA was an independent predictor of poor physical function following TKA after adjusting for preoperative physical performance. Numerous factors, including pain, knee extension muscle strength, and comorbidities, have been suggested to affect the physical performance of patients with knee OA41. Our results are in line with those of previous studies and also showed that a low PhA itself should be considered as an influential factor, even though the PhA and other factors seem to have a bidirectional effect. In addition, there was no significant difference in pain intensity between the low and high PhA groups before and after surgery, which was previously identified as the main factor impeding physical function41. This potentially indicates that pain and PhA are not related, or it might be due to the characteristics of our study population, who had moderate-to-severe pain and were awaiting surgery.

Our multivariable analysis revealed that a lower peak flexion torque at 60º/s on the asymptomatic side was an independent predictor of poor physical function after TKA. Although the quadriceps muscle is a major determinant of physical function42 the hamstring is also important as an antagonist to the quadriceps43. Altered muscle activation patterns, such as increased hamstring activity and reduced quadricep muscle fiber recruitment, have been described in patients with knee OA44,45. A low peak flexion torque may reflect a decline in hamstring activity, potentially reducing knee stability45.

This study has some limitations. First, selection bias may exist because the study included patients who desired surgical treatment. Second, we did not address all pre-, intra-, and postoperative factors that might affect postoperative physical performance. Third, the low follow-up rate could have led to a survival bias; patients who successfully experience functional recovery may not return for follow-up visits. The pre–post comparison might have underrepresented these patients. However, our sample size (n = 63) provided adequate statistical power to detect significant differences between the low and high PhA groups. In addition, the follow-up rate of the low (32%) and high PhA groups (26%) showed no significant difference (Χ2 = 0.816, df = 1, P = .37), suggesting that the PhA did not influence the drop-out rate. Future studies should consider strategies to improve follow-up rates and minimize potential survival bias. Fourth, we did not assess long-term functional recovery. However, it has been reported that the greatest recovery occurs in the first 3 months, with no or minimal increment after that4. We believe that our findings may reflect long-term prognosis and will be helpful in establishing patients’ care plan. Fifth, the single-center design may limit the generalizability of the findings to other populations or clinical settings. Although the PhA alone may not fully predict the development of knee OA, requirement for TKA, or postoperative function, our findings support its potential clinical utility in preoperative risk stratification. Further studies are needed to examine the prognostic value of PhA across various clinical settings, explore its long-term effects, identify modifiable factors associated with the PhA, and develop targeted interventions to mitigate the risks associated with a low PhA.

In conclusion, patients with knee OA with a low PhA exhibited decreased muscle strength and physical function compared with that of those with a high PhA. A low PhA is an independent risk factor for poor physical performance after TKA. Measuring PhA using BIA might be helpful in predicting postoperative outcomes in this population, although physical performance and strength cannot be measured because of severe pain and gait disturbances.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not openly available to protect study participant privacy and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Collaborators, G. B. D. O. Global, regional, and national burden of osteoarthritis, 1990–2020 and projections to 2050: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Rheumatol. 5, e508-e522. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2665-9913(23)00163-7 (2023).

McAlindon, T. E., Cooper, C., Kirwan, J. R. & Dieppe, P. A. Knee pain and disability in the community. Br. J. Rheumatol. 31, 189–192. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/31.3.189 (1992).

McDonough, C. M. & Jette, A. M. The contribution of osteoarthritis to functional limitations and disability. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 26, 387–399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cger.2010.04.001 (2010).

Wieczorek, M., Rotonda, C., Guillemin, F. & Rat, A. C. What have we learned about the course of clinical outcomes after total knee or hip arthroplasty?? Arthritis Care Res. 72, 1519–1529. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.24045 (2020).

Srivastava, A. K. Surgical management O. O.teoarthritis O. T.e knee work group, S. O. T. A. A. O. O. S. American academy O. orthopaedic surgeons clinical practice guideline summary O. surgical management O. O.teoarthritis O. T.e knee. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 31, 1211–1220. https://doi.org/10.5435/JAAOS-D-23-00338 (2023).

Cooper, N. A. et al. Predictors of multidimensional functional outcomes after total knee arthroplasty. J. Orthop. Research: Official Publication Orthop. Res. Soc. 35, 2790–2798. https://doi.org/10.1002/jor.23596 (2017).

Berghmans, D. D. P., Lenssen, A. F., Emans, P. J. & de Bie, R. A. Functions, disabilities and perceived health in the first year after total knee arthroplasty; a prospective cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 19, 250. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-018-2159-7 (2018).

Olsen, U. et al. Factors correlated with physical function 1 year after total knee arthroplasty in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open. 5, e2219636. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.19636 (2022).

Harmelink, K. E. M. et al. Are there prognostic factors for one-year outcome after total knee arthroplasty? A systematic review. J. Arthroplasty 32, 3840–3853. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2017.07.011 (2017).

Overgaard, A., Lidgren, L., Sundberg, M., Robertsson, O. & A, W. D. Patient-reported 1-year outcome not affected by body mass index in 3,327 total knee arthroplasty patients. Acta Orthop. 90, 360–365. https://doi.org/10.1080/17453674.2019.1604940 (2019).

Kumar, D. et al. Quadriceps intramuscular fat fraction rather than muscle size is associated with knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 22, 226–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2013.12.005 (2014).

Chopp-Hurley, J. N., Wiebenga, E. G., Bulbrook, B. D., Keir, P. J. & Maly, M. R. Evaluating the relationship between quadriceps muscle quality captured using ultrasound with clinical severity in women with knee osteoarthritis. Clin. Biomech. (Bristol). 80, 105165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2020.105165 (2020).

Kyle, U. G. et al. Bioelectrical impedance analysis-part II: utilization in clinical practice. Clin. Nutr. 23, 1430–1453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2004.09.012 (2004).

Sardinha, L. B. & Rosa, G. B. Phase angle, muscle tissue, and resistance training. Reviews Endocr. Metabolic Disorders. 24, 393–414. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11154-023-09791-8 (2023).

Wada, O., Kurita, N., Yamada, M. & Mizuno, K. Structural severity, phase angle, and quadriceps strength among patients with knee osteoarthritis: the SPSS-OK study. Clin. Rheumatol. 39, 3049–3056. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-020-05056-w (2020).

Homma, D. et al. Motor function is related to the lower phase angle than to muscle mass of the lower limbs in older females with hip osteoarthritis: a cross-sectional observational study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 25, 720. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-024-07833-z (2024).

Lane, N. E. et al. OARSI-FDA initiative: defining the disease state of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 19, 478–482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2010.09.013 (2011).

von Elm, E. et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 61, 344–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008 (2008).

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A. & Lang, A. G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods. 41, 1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.3758/brm.41.4.1149 (2009).

Liao, C. D., Chen, H. C., Huang, S. W. & Liou, T. H. Impact of sarcopenia on rehabilitation outcomes after total knee replacement in older adults with knee osteoarthritis. Ther. Adv. Musculoskelet. Dis. 13, 1759720x21998508. https://doi.org/10.1177/1759720x21998508 (2021).

Otsubo, R. et al. Phase angle is related to physical function and quality of life in preoperative patients with lumbar spinal stenosis. Sci. Rep. 13, 13909. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-40629-0 (2023).

Craig, C. L. et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med. Sci. Sports. Exerc. 35, 1381–1395. https://doi.org/10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB (2003).

Chen, L. K. et al. Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia: 2019 consensus update on sarcopenia diagnosis and treatment. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 21, 300–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2019.12.012 (2020).

Paley, D., Herzenberg, J. E., Tetsworth, K., McKie, J. & Bhave, A. Deformity planning for frontal and sagittal plane corrective osteotomies. Qld. Gov. Min. J. 25, 425–465 (1994).

Unver, B. et al. Reliability of 4-meter and 10-meter walk tests after lower extremity surgery. Disabil. Rehabil. 39, 2572–2576. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2016.1236153 (2017).

Steffen, T. M., Hacker, T. A. & Mollinger, L. Age- and gender-related test performance in community-dwelling elderly people: Six-Minute walk test, Berg balance scale, timed up & go test, and gait speeds. Phys. Ther. 82, 128–137. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/82.2.128 (2002).

Kiyohara, M. et al. Evaluation of the balance function before and after total knee arthroplasty using Berg balance scale. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 142, 3461–3467. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-021-04233-z (2022).

Wang, X. F., Ma, Z. H. & Teng, X. R. Isokinetic strength test of muscle strength and motor function in total knee arthroplasty. Orthop. Surg. 12, 878–889. https://doi.org/10.1111/os.12699 (2020).

Buckinx, F. et al. Concordance between muscle mass assessed by bioelectrical impedance analysis and by dual energy X-ray absorptiometry: a cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 16, 60. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-015-0510-9 (2015).

Yang, J., Kim, J., Chun, B. C. & Lee, J. M. Cook with different pots, but similar taste?? Comparison of phase angle using bioelectrical impedance analysis according to device type and examination posture. Life (Basel Switzerland). 13, 523. https://doi.org/10.3390/life13051119 (2023).

Uemura, K. et al. Predictivity of bioimpedance phase angle for incident disability in older adults. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 11, 46–54. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.12492 (2020).

Mason, J. B., Fehring, T. K., Estok, R., Banel, D. & Fahrbach, K. Meta-analysis of alignment outcomes in computer-assisted total knee arthroplasty surgery. J. Arthroplast. 22, 1097–1106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2007.08.001 (2007).

Custodio Martins, P., de Lima, T. R., Silva, A. M. & Santos Silva, D. A. Association of phase angle with muscle strength and aerobic fitness in different populations: a systematic review. Nutr. (Burbank Los Angeles Cty. Calif). 93, 111489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2021.111489 (2022).

Yamada, M. et al. Phase angle is a useful indicator for muscle function in older adults. J. Nutr. Health Aging. 23, 251–255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-018-1151-0 (2019).

Bourgeois, B. et al. Improved strength prediction combining clinically available measures of skeletal muscle mass and quality. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 10, 84–94. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.12353 (2019).

Noehren, B. et al. Alterations in quadriceps muscle cellular and molecular properties in adults with moderate knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 26, 1359–1368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2018.05.011 (2018).

Mathiessen, A. & Conaghan, P. G. Synovitis in osteoarthritis: current Understanding with therapeutic implications. Arthritis Res. Ther. 19 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-017-1229-9 (2017).

Sharma, L. et al. Significance of preradiographic magnetic resonance imaging lesions in persons at increased risk of knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 66, 1811–1819. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.38611 (2014).

Lusardi, M. M. et al. Determining risk of falls in community dwelling older adults: a systematic review and Meta-analysis using posttest probability. J. Geriatr. Phys. Ther. 40, 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1519/JPT.0000000000000099 (2017).

Clegg, A., Young, J., Iliffe, S., Rikkert, M. O. & Rockwood, K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet (London England). 381, 752–762. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62167-9 (2013).

de Rooij, M. et al. Prognosis of pain and physical functioning in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Arthritis Care Res. 68, 481–492. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.22693 (2016).

Moxley Scarborough, D., Krebs, D. E. & Harris, B. A. Quadriceps muscle strength and dynamic stability in elderly persons. Gait Posture. 10, 10–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0966-6362(99)00018-1 (1999).

Lopes, H. S. et al. There is more to the knee joint than just the quadriceps: a systematic review with meta-analysis and evidence gap map of hamstring strength, flexibility, and morphology in individuals with gradual-onset knee disorders. J. Sport Health Sci. 13, 521–536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2023.08.004 (2024).

Kaufman, K. R., Hughes, C., Morrey, B. F., Morrey, M. & An, K. N. Gait characteristics of patients with knee osteoarthritis. J. Biomech. 34, 907–915. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0021-9290(01)00036-7 (2001).

Hortobagyi, T. et al. Altered hamstring-quadriceps muscle balance in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Clin. Biomech. (Bristol). 20, 97–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2004.08.004 (2005).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a new faculty research seed money grant of Yonsei University College of Medicine, Republic of Korea (2024-32-0066). The funders had no role in the study design, in the data extraction, analysis and interpretation of data, in the writing of manuscript, and in the final decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YSK: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualisation, Writing - Original draft, Review & editing ; SIC: Data curation, Investigation, Writing - Review & editing; JYP: Formal analysis, Investigation, Validation, Writing - Review & editing; HWY: Data curation, Investigation, Writing - Review & editing; WL: Data curation, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing - Review & editing; SK: Supervision, Validation, Writing - Review & editing; KC: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing - Review & editing; NYK: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Writing - Review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, Y.S., Choi, S.I., Park, J.Y. et al. Low phase angle indicates poor muscle strength and physical performance in patients with knee osteoarthritis awaiting total knee arthroplasty. Sci Rep 15, 27511 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13065-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13065-5