Abstract

As an important component of the building, the sound insulation performance (SIP) of doors greatly influences the quality of the indoor acoustic environment. Therefore, this paper presents a systematic study on the SIP of wooden doors. Firstly, this study comparatively analyzes SIP across distinct core structures in both fully assembled door systems and isolated door panels, aiming to identify frequency-dependent acoustic variations across standardized bands. Secondly, acoustic finite element modeling and Gompertz’s theory of the rectangular gap sound transmission coefficient are used to further analyze the SIP of the wooden door structure across different frequency bands. This reveals the inherent relationship between the core structure, the sealing material, and the SIP of the wooden door. The results show that the SIP of the three core structures for the entire door can range from 24 dB to 27 dB. Among them, the core structure has a greater impact on low-frequency SIP, while the sealing structure has a more notable effect on high-frequency SIP. Therefore, after optimizing the wooden door design, the sound SIP can be increased by 5 dB to 8 dB. This study establishes a theoretical framework and practical design protocols for high-performance sound-insulated wooden doors, critically enabling architectural acoustic environment optimization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The indoor sound insulation environment aims to meet people’s needs for privacy, noise reduction, and comfort. In modern society, the pursuit of private sound space and confidentiality is increasing1,2,3. The sealing performance of indoor wooden doors has deteriorated over time, which affects their soundproofing ability4,5,6,7,8. Therefore, it is essential to create sound-insulated independent spaces and improve the sound insulation performance (SIP) of interior wooden doors. The design and research of soundproof wooden doors aim to provide adequate sound insulation, block noise transmission, and create a peaceful space separated from the outside environment9. However, in the field of scientific research, studies on the variations in the SIP of doors and their acoustic properties across different frequency ranges remain limited. Furthermore, research on optimizing the wooden door structure and improving its SIP is also underdeveloped, which somewhat limits the advancement and use of high acoustic performance in wooden doors. Consequently, the necessity to enhance the SIP of interior wooden doors has become a pivotal concern for industry10.

Currently, wooden doors typically use a sandwich composite structure11,12, and their core design approach is to optimize performance through functional layering. Specifically: as the outer protective layer of the structure, the surface board typically use high-stiffness and high-strength composite materials (such as Medium-density fiberboard (MDF)11,12, Laminated veneer lumber (LVL)13 or solid wood veneer14,15, that directly bear external mechanical loads, resist environmental erosion, and dominate the overall bending stiffness of the material. The core structure acts as the sandwich filling layer, positioned between the two-surface boards. Its core functions include: (1) achieving lightweight design through lightweight porous structures like hollow particleboard or honeycomb particleboard, (2) dissipating vibration energy by using damping materials such as rubber layers or air gaps, and (3) enhancing acoustic performance, for example, by improving sound insulation through impedance mismatch. This layered design not only provides structural strength but also greatly improves sound insulation, seismic resistance, and cost-effectiveness of wooden doors, making it a common technical solution in modern door manufacturing16,17. Therefore, improving the SIP of wooden doors mainly involves replacing the surface materials, adjusting the core structure, and decreasing the density of the joists. For example, using laminated veneer with a galvanized steel sheet surface can enhance low-frequency resonance and increase the SIP of the sheet by 7 dB18,19. The composite material made of wood and glass fiber can achieve a SIP of 22 dB, with the sound insulation of glass fiber being only 3 dB. From this, it is clear that wood plays a crucial role in sound absorption, which is closely related to the sound insulation and absorption properties of wood, as well as its density, porosity, and thickness, with porosity having the greatest impact19. Secondly, for medium and high-density wood wool boards made from plant fibers, the SIP of high-density (1.0 g/cm³) fiberboard is 15 dB higher than that of low-density (0.8 g/cm³) fiberboard20,21. This indicates that the material’s density is also a crucial factor affecting the SIP. Additionally, the board’s thickness significantly impacts the SIP at low and high frequencies range22,23. As summarized, the current focus on improving the SIP of wooden doors mainly centers on the SIP of the boards, but it overlooks the SIP of the entire door once the boards are turned into door panels and attached to the door frame with hardware.

Therefore, this study aims to thoroughly investigate the SIP of the entire door. First, it examines the acoustic performance characteristics and SIP of different core structures on the door leaf and the entire door across various frequency ranges. Second, the study uses Gompertz’s rectangular gap sound transmission coefficient theory and acoustic finite element modeling to thoroughly analyze the SIP characteristics of wooden doors in different frequency bands. This theoretical framework provides a strong basis for future optimal design. Finally, based on the results, a high-SIP wooden door is designed, and its performance is verified through SIP experiments. The main goals of this research are threefold: first, to explore the intrinsic link between the door’s structure and its SIP; second, to reveal the frequency domain characteristics of wooden door SIP; and third, to offer scientific guidance for designing high-performance wooden doors. The findings have significant theoretical value and provide important technical support for practical engineering, promoting the development and adoption of high-performance sound-insulating wooden doors and contributing to the improvement of the acoustical environment in buildings.

Materials and methods

Materials

MDF was obtained from DARE GLOBAL, while vertical corrugated board (corrugated height: 9 mm; corrugated width: 4 mm; corrugated thickness: 0.2 mm) was obtained from Shenzhen Long-Feel Display Co., Ltd. Hollow extruded particleboard and homogeneous extruded particleboard (aperture: 30 mm) were obtained from Sauerlander Spanplatten GmbH. Rubber was obtained from Shijiazhuang Electric Power Equipment Manufacturing Co., Ltd. LVL was obtained from Jiangsu Fuqing Wood Co., Ltd. Emulsion glue was obtained from Henkel AG & Co., and Self-declining door bottom sound insulators were obtained from ASSA ABLOY (Schweiz) AG. AWA6290L multi-channel signal analyzer, ACE4001 power amplifier, microphone, and dodecahedron Loudspeaker were obtained from Hangzhou Aihua Instruments Co. The other basic processes of the material are shown in Table 1.

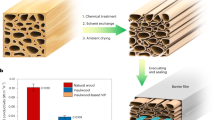

Preparation of wooden door materials

The sample preparation process is shown in Fig. 1. First, prepare the MDF boards and keep their surfaces clean. Next, polyvinyl acetate emulsion droplets are deposited in a straight-line pattern onto the facing veneer, followed by brushing to create an interconnected adhesive grid networks24. Then, combine the panel with different core structures and surface board them in the press. The pressure is set at 0.2 MPa, the time at 4 h, and the temperature at room temperature (25℃±3). To study the SIP of door leafs with different core structures, which mainly include four types. Among them, the densities of the sandwich composite materials prepared with extruded particleboard (hollow), extruded particleboard (homogeneous), and vertical corrugated board as core structures and MDF as surface boards are 433 kg/m³, 517 kg/m³, and 302 kg/m³, respectively.

Wooden doors preparation

The structure of the door leaf is illustrated in Fig. 2. It utilizes a 40 mm wide LVL as the keel (Fig. 2a) for various core configurations. The door leaf measures 810 mm in width, 2090 mm in height, and 46 mm in thickness (Fig. 2b) respectively.

Acoustic characterization

The reverberant chamber method is a relatively mature test method for the sound insulation testing of significant building components, such as interior wooden doors. According to the standards ASTM E90-23 ‘Standard Test Method for Laboratory Measurement of Airborne Sound Transmission Loss of Building Partitions and Elements‘25 and ISO 10140-2:2021 ‘Acoustics Laboratory measurement of sound insulation of building elements Part 2: Measurement of airborne sound insulation‘26, there are two configurations of the reverberant chamber method for testing the SIP of reverberant chambers: the reverberant chamber double chamber method with reverberant chambers on both the source and receiver sides, and the reverberant chamber-anechoic chamber double chamber method with reverberant chambers and anechoic chambers on both the source and receiver sides, respectively.The two commonly used two-chamber configurations are employed to calculate the acoustic transmission loss of the component from the incident power and the transmitted power. Therefore, this study adopts the reverberation chamber - anechoic chamber dual-chamber method (Fig. 3, Table 2). The entire door acoustic insulation performance test was conducted at the wooden door mute laboratory of Opie Home Furnishing Group Co. Ltd., and the door acoustic insulation performance test was carried out at the National Building Materials Testing Centre of China National Inspection & Testing Co. In the SIP test, the sealing material for the gaps at the door leaf boundary is rubber strips. The entire door is connected to the door leaf and the door frame through hardware.

The two-chamber method for calculating the sound transmission loss (STL) of a building component, such as a wooden door, is defined as the ratio of the total incident power of the building28\(\:{P}_{in}\), to the total transmitted power of the component, \(\:{P}_{tr}\), i.e.:

The incident power on the surface of the specimen in an ideal scattering steady state sound field can be calculated by analysing the incident power \(\:{P}_{in}\) in the reverberation chamber.

The area of the reverberation chamber specimen (i.e. the area of the wooden door) is denoted by \(\:{S}_{S}\). The root mean square (RMS) pressure of the reverberation chamber is indicated by \(\:{P}_{rms}\). The density is denoted by \(\:\rho\:\) and the speed of sound by \(\:c\).

The transmitted power \(\:{P}_{tr}\) of the anechoic chamber is thus:

For planar specimens, \(\:{S}_{r}={S}_{s}\). When this is combined with Eqs. 1, 2, and 3, the result is \(\:STL\):

where \(\:{P}_{ref}\)=20\(\:\mu\:\)Pa, \(\:{I}_{ref}\)=1012W/m, \(\:\rho\:\)=1.2 kg/m3, \(\:c\)=343 m/s, \(\:{SPL}_{s}\) is the mean sound pressure level of the reverberation room, and \(\:{SIL}_{tr}\) is the mean sound intensity level of the anechoic room.

Results and analyses

Influence of core structure on the acoustic performance of the entire door

The entire door consists mainly of two parts: the door leaf and the door frame. The door leaf has the largest area and is the main component, which determines the SIP of the entire door. However, the SIP of the door leaf is primarily influenced by the surface board and the core structure (Fig. 4).

Figure 5 displays the sound insulation curves for the four core structures across different frequencies. In the low-frequency range, high-density and high-strength flat extruded particleboard improves the connection strength between hardware connectors and the door leaf, enhancing the SIP. In the resonance effect area, the sound insulation curve of the homogeneous extruded particleboard door leaf, which has superior damping properties, is comparatively smoother at resonance frequencies and shows no noticeable sound insulation dip. Conversely, the flat extruded particleboard, due to its uniform and low damping characteristics, is more noticeably influenced by resonance and creates deeper troughs. In the mid-frequency range, the SIP depends on density. Therefore, homogeneous extruded particleboard demonstrates better SIP than hollow extruded particleboard. In this mid-frequency range, the corrugated board door leaf’s point glue line process is used to create a multi-layer panel coupling structure. When sound waves impact it, the corrugated surface is excited and vibrates, causing the panel to periodically detach from the adjacent air layer (local vacuum effect). This separation results in a characteristic impedance mismatch in the plate-gas coupling system, causing the panel to undergo significant elastic deformation. Meanwhile, the compressed air layer acts as an equivalent air “spring” due to volume changes, storing and releasing acoustic energy. This phenomenon leads to the reduction of vibration between the two panels, thereby decreasing energy transfer. Secondly, the critical frequency of the anastomosis effect in the composite plate depends on the critical frequencies of each side of the structure. The corrugated structure causes these critical frequencies to stagger, which suppresses the anastomosis trough caused by the coupling frequency. The high-frequency sound insulation curve is smoother compared with other structures. The plain particleboard door is affected by the coupling frequency, resulting in many coincident valleys that impact its overall SIP. The weighted sound insulation of the homogeneous extruded particleboard and vertical corrugated board door leaf is 27 dB. In contrast, the more resonance- and coupling-sensitive overall homogeneous particleboard door leaf has a weighted sound insulation of 25 dB. The hollow extruded particleboard door leaf, characterized by low density and poor stiffness, has a weighted sound insulation of only 24 dB.

The excellent sound insulation of flat extruded particleboard stems from its continuous micro-porous structure. When sound waves strike the surface, some are reflected while others penetrate into the porous interior. Inside, air vibrations cause particles and debris to rub against each other. Through viscosity and heat conduction, sound waves continue inward, gradually transforming into heat energy that dissipates. This process aligns with Huygens’ principle. Vertical corrugated board also contains many small holes. When sound waves hit the inside of the corrugated board, they cause the air in the corrugated cells to vibrate and rub against the cell fibers. This vibration spreads and diminishes as it reflects off the rigid surface of the board and kraft paperboard. As a result, standing wave resonance in the cavity is eliminated, and the acoustic pressure decreases, helping the board achieve its soundproofing goal insulation29,30,31. From the perspective of vibration energy transfer, extruded particleboard is made of loosely stamped particles, leading to low inter-particle bonding strength and relatively low rigidity. Consequently, extruded particleboard is not very effective as an acoustic bridge for efficiently transferring sound vibrations. However, its good damping properties positively influence the suppression of low-frequency resonance and high-frequency valley effects. Vertical corrugated board consists of a bent corrugated base layer laminated to a flat base layer, then attached to the surface board. This process helps prevent relative motion of the surface board by utilizing its internal damping, which reduces bending vibrations and thereby improves sound insulation performance across the entire frequency range. This method is particularly effective in minimizing low-frequency resonance and preventing coupling effects that reduce sound insulation.

Influence of the core structure on the acoustic performance of doors

This chapter systematically quantifies SIP disparities among three door panel architectures: hollow extruded particleboard cores, homogeneous extruded particleboard, vertical corrugated board, and their fully assembled door systems. Additionally, it investigates the governing influence of mechanical hardware interfaces and peripheral sealing systems (including gap geometries and connection materials) on the composite SIP of integrated door assemblies32. As Fig. 6 demonstrates, the entire door exhibits increased SIP at low frequencies compared to the isolated door leaf alone. This is because the SIP of the door leaf depends on the stiffness of the hardware connections (the density of iron is 7850 kg/m³) and its own stiffness in a very low frequency range (below the simple normal frequency of the door leaf). Conversely, during the SIP test of the door leaf, the gaps are sealed with rubber cues (the density of rubber is 1.5 kg/m³)33. Compared to ferrous hardware, elastomeric components (rubber cues) exhibit reduced density (1100 kg/m³vs 7850 kg/m³) and elastic modulus (0.01 GPa vs. 210 GPa), diminishing low-frequency SIP in door panels due to compromised mass-law attenuation. Conversely, mid-to-high frequency SIP of isolated door panels exceeded fully assembled systems by 8.2 ± 1.5 dB, attributable to circumferential sealing with viscoelastic damping materials that eliminated flanking transmission pathways during laboratory testing per ISO 10140-2. In contrast, during the entire door test, there were gaps in the sealing strips installed around the door leaf and in the acoustic insulating strips at the bottom. These gaps may cause sound leakage and could impact the SIP compared to the door’s complete sealing34. Regarding the sound insulation deficiencies in the mid- and high-frequency ranges of the entire door, the weighted sound insulation of doors made from hollow extruded particleboard, double-layered vertical corrugated board, and homogeneous extruded particleboard was found to be 5 dB. This is 4 dB and 9 dB higher than the sound insulation of the door leaf, respectively. While improving the door leaf structure with extruded particleboard enhanced its acoustic insulation, the overall sound insulation performance of the entire door did not improve significantly. This suggests that once the SIP of the door leaf structure reaches a certain point, further enhancement of the door’s overall SIP by only improving the door leaf structure becomes difficult.

Frequency domain analysis of wood door insulation curves

The sound insulation curves of the three different door leaf and door structures, as described in 3.2, show a marked difference at high frequencies. Furthermore, the door edge and bottom strip seals are considered incomplete during the sound insulation test of the entire door, resulting in a residual gap that reduces overall sealing effectiveness compared to the test of the door leaf alone. To analyze how the gap between the door leaf, the entire door, and the floor affects sound transmission at various frequencies, Gompertz’s rectangular gap sound transmission coefficient theory is used for derivation35.

If the areas of the door leaf and the door gap are \(\:{S}_{1}\) and \(\:{S}_{2}\) respectively, and the transmission coefficients are \(\:{\tau\:}_{1}\) and \(\:{\tau\:}_{2}\) respectively, then the total door sound insulation \(\:STL\), taking into account only the door gap and the door leaf, can be expressed as

The transmission coefficient \(\:{\tau\:}_{2}\) of the rectangular slit can be derived from the theoretical calculation of Gomperts’ rectangular slit transmission coefficient as follows:

In the context of the two-chamber method, the following parameters are of significance: \(\:X=d/w\), where \(\:d\) signifies the depth of the gap, that is, the thickness of the door, and \(\:w\) denotes the width of the gap, that is, the width of the door. The parameter \(\:K=kw\), where \(\:k\) is the number of waves, and \(\:p\) is the incidence parameter of the acoustic field. In the case of a diffuse acoustic field, \(\:p\)=8, and the case of a direct acoustic field, \(\:p\)=4. It is important to note that the two-chamber method is a reverberant experimental condition; therefore, \(\:p\)=8. The positional parameter, \(\:n\), is also of significance. In this case, \(\:n\)=1 corresponds to the gap being in the three circumferences of the wooden door, while \(\:n\)=0.5 corresponds to the gap being at the bottom of the wooden door. Finally, e is the correction, which is given by:

The derivation of the formula indicates that the door seams have a greater impact on the SIP, with the door width and height having a more significant effect on sound insulation than door thickness.

With a constant door thickness and width, it was observed that leakage increased as frequency and gap size increased. Additionally, it was found that sound leakage through the gap significantly affected the SIP at middle and high frequencies36. This finding confirms the previous test of the SIP of the door leaf and the entire door. By simulating random noise in the living environment in the laboratory, it shows that the gap at the bottom of the wooden door has a greater effect on the SIP than the gap near the door edge. This indicates that improving the SIP at the bottom of the wooden door is more important than at the door edge. The sound insulation curves of the door leaf from three different structures and the entire door show that, aside from a noticeable difference at high frequency, the curves for the door leaf with various infill materials display a clear trough between 125 Hz and 200 Hz. In this range, the sound insulation performance of the door leaf is significantly lower than that of the entire door. To diagnose the abnormal attenuation in this frequency trough, acoustic finite element modeling simulations were performed to analyze the surface sound pressure distribution and the corresponding vibration modes of the door structure under acoustic excitation. The principle of Acoustic FEM involves dividing the solution domain into a series of interconnected cells and describing the variables within these cells by using interpolation functions. The acoustic FEM are solved using variational and weighted residual methods, combined with boundary conditions such as acoustic pressure, impedance, and plasmonic vibration velocity, to determine the node variables, thus providing an approximate numerical solution for the variables at the nodes. This analysis method offers a better understanding of the causes behind the formation of low valleys in the doors’ acoustic performance. The reverberation chamber-anechoic chamber method used in the two-chamber technique is employed for sound insulation testing of wooden doors in a laboratory setting. The specimen structure and the two-chamber conditions are modeled using acoustic FEM according to the schematic diagram of the reverberation chamber-anechoic chamber simulation shown in Fig. 7. Due to the significant amount of computation needed, the reverberation chamber is assumed to be an ideal diffusion field, based on the theory of the reverberation chamber-anechoic chamber method. The anechoic chamber is considered to be an ideal anechoic terminal37. It is essential to ensure that the specimen has minimal impact on the reverberation chamber sound field under the current simulation conditions. The surface of wooden door products is typically a veneer wood panel with low acoustic absorption properties and relatively rigid, making this structure suitable for acoustic FEM of wooden doors.

As shown in the simulation structure schematic (Fig. 8a), the reverberation and anechoic chambers are set up as pressure acoustics in the COMSOL software, with the wooden door modeled as solid mechanics. The surface load pressure of the wooden door on the reverberation room side is designated as \(\:{P}_{door}\). The sound pressure in the air domain is completely absorbed using a perfect matching layer (PML) on the anechoic room side. The sound wave in the reverberation room is an ideal diffusion field at random incidence, and the reverberation room can be defined as a sum of \(\:N\) uncorrelated plane waves moving in a random direction, and \(\:1/\sqrt{N}\) ensures that there is a constant strength in the reverberation room field, and the reverberation room pressure field \(\:{P}_{room}\) is:

where θ_n and φ_n are level angle random numbers and Φ_n is a phase random number.

The wooden door (x = 0 plane) is a reflective diffuse field with a diffuse field reflective component:

Combining the above two equations, the pressure load on the surface of the wooden door is the sum of the reverberation chamber diffusion field pressure and the reflected diffusion field pressure on the surface of the wooden door:

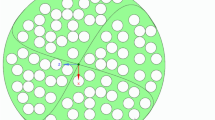

The geometrical model is built as shown in Fig. 8b, and the dimensions of the door model are based on the specifications of the homogeneous extruded particleboard door. The door measures 2090 mm in height, 810 mm in width, and 46 mm in thickness. It is simulated and analyzed using the acoustic-stationary coupling module in COMSOL software. The grid modeling setup is depicted in Fig. 8c. The door leaf and the perfect matching layer use a swept John grid, with minimum and maximum cell sizes set to 1/6 and 1/5 of the ratio between the air pressure wavelength and the highest study frequency, respectively. The fixing method around the sides of the door leaf is set to a fixed boundary. A reverberation chamber is simulated on the front side of the door model to apply loads to the door. When the sound wave passes through the door, an anechoic chamber is modeled in the air domain wrapped with a PML on the receiving side. The acoustic transmission loss is calculated from the sound power passing through both sides of the door at 1/3-octave frequencies ranging from 100 to 5000 Hz.

As shown in Fig. 9, comparing the experimental and simulated values for the homogeneous extruded particleboard doors reveals a significant discrepancy in the SIP between the two data sets. The simulated values show notably higher performance in the low-frequency boundary effect region compared to the actual measurements. This difference arises from the variation in fixed constraints used in the simulation versus the ‘simply supported’ conditions in the actual test, which resemble hinges or visco-elastic materials (i.e., mass boundaries). This disparity greatly influences the low-frequency stiffness control region of the sound insulation curve, where increasing boundary stiffness improves SIP within this frequency range. In the low and middle frequency regions, there is a strong correlation between the simulation and experimental results, indicating that the simulation model can accurately predict the SIP of the door in this frequency band. This confirms the validity of the FEM for studying sound insulation troughs from 125 Hz to 200 Hz and offers a solid foundation for further analysis.

A comparison of the simulation with the actual situation revealed the presence of sound insulation troughs in both the door leaf at 160 Hz and the displacement of the door leaf and the pressure distribution inside the receiving chamber, which were simulated at this frequency. As shown in Fig. 10a, a single displacement bump appears for the door leaf. The displacement distribution at this frequency is significantly affected by potential structural modes, with the displacement controlling the transmitted intensity field, and the pressure distribution within the receiving chamber displaying two distinct components, one above and one below. The first two orders of intrinsic frequency were calculated, and the displacement structural modes were simulated for the door. These frequencies are 146.99 Hz and 170.46 Hz, respectively, with the corresponding displacement modes shown in Fig. 10b and c. The valley at 160 Hz on the acoustic isolation curve corresponds to the structural modes between the first two orders of intrinsic frequency. The boundary stiffness and the rigidity of the door itself influence the door’s acoustic performance, which is highly dependent on the boundary conditions applied to the structure below these frequencies. Above the first two intrinsic frequencies, the acoustic performance is mainly governed by mass law properties. Material properties were varied, and it was found that sound insulation troughs persisted between 120 Hz and 200 Hz. For the entire door, changes in structural dimensions and boundary conditions affect the generation of the door’s intrinsic frequency in relation to the acoustic resonance effect, which suppresses the sound insulation troughs. In the frequency range of 120 Hz to 200 Hz, the sound insulation of the door is affected by the structural modes corresponding to the intrinsic frequencies. It can be concluded that the inherent frequency has a greater impact on the low-frequency acoustic performance of wooden doors, with the size of the door leaf being the main factor affecting the intrinsic frequency.

Optimised design of sound-insulating structures for wooden doors

The enhancement of the door sealing structure mainly targets the door edge and the bottom sections. Two main types of indoor wooden doors are identified: the flat door and the T-shaped door. The difference between these types lies in the configuration of the door edge. The flat door (Fig. 11a) has a flat door edge, and when closed, the door edge is sealed by a sealing strip that covers the entire door seal. In contrast, the T-shaped door (see Fig. 11b) features a door edge sealed by a strip, which is attached to the door seal. b) Opening: from the top of the door, the opening resembles the letter ‘T’. After closing, the protruding edge presses against the door cover, passing through the door cover and the gap between the door cover and the door, completing the closure. The adhesive strip between the door cover and the opening provides an effective seal. The T-shaped door has become a popular trend in panel furniture in China, Japan, the United States, and other countries, while the flat door remains the most common type of interior wood door. The T-shaped door was popular in Europe during World War II and has gradually become the dominant door style in European countries. The T-shaped door’s sealing performance is improved by the enterprise’s mouth sealing strip and door edge sealing strip, which are created by the cavity sound insulation structure. According to Gomperts’ theory of rectangular gap sound transmission coefficient, the impact of the gap at the bottom of the door on the overall door’s sound insulation is greater than that of the gap at the door’s edge. Therefore, this section suggests an enhancement to the structure of the self-lowering sound isolation strip, based on the principle of cavity sound insulation. This leads to the development of a double door bottom sound isolation strip, as shown in Fig. 11c. When the door is closed, these two sound isolation strips form a cavity structure, improving the sealing performance.

As previously established, the size significantly influences the intrinsic frequency of the door leaf. To improve the SIP at this stage, it is essential to reduce the amplitude of the resonance trough by increasing the damping performance. For this purpose, the shear-type constrained damping structure in Fig. 11d is used to suppress door resonance. This structure includes three layers of extruded particleboard laminated with two layers of rubber damping material, as shown in Fig. 11e. In this setup, the fiberboard sheet functions as the base layer, the rubber acts as the damping layer, and the extruded particle board on both sides serves as the spacer and restraining layer. The spacer layer increases both the mass and the loss factor of the plate and further enhances the tensile strength of the damping layer. When the plate bends under acoustic excitation, the deformation of the restraining layer is much greater than that of the damping layer. Consequently, the damping layer helps prevent the stretching and compression of the elastic layer, reducing the bending deformation of the plate. The damping layer prevents the elastic layer from stretching and compressing, thereby decreasing the plate’s bending deformation. Located on the opposite side of the structure, the extruded particleboard acts as a restraining layer, limiting the movement of the rubber material. This creates alternating shear stresses and strains within the damping layer, leading to an increased structural loss factor and aiding in the control of multi-peak resonance at both low and high frequencies.

As demonstrated in Fig. 12, the extruded particleboard rubber composite panel door leaf with a shear-type constrained damping structure effectively controls resonance within the low-frequency structural resonance zone, resulting in a smooth resonance trough. In the mid-frequency surface mass region, the three structural masses are similar and do not show significant differences in sound insulation. However, at frequencies above 500 Hz, the double door bottom sound insulation strip and T-door sealing enhancement exhibit a considerable increase in SIP, as does the extruded particle board rubber composite panel door leaf enhancement. These results confirm the important role of the constrained damping structure in managing multi-peak resonance at both low and high frequencies. The weighted values for the single door leaf, the single door leaf door bottom acoustic strip, and the T-shaped door at the door bottom are 27 dB, 29 dB, and 32 dB, respectively. These values closely match the expected values based on the experimental data.

Conclusion

The study examines the SIP of wooden doors through experimental benchmarking, acoustic finite element modeling, and multi-objective optimization. It measures factors affecting SIP across different frequency ranges and develops an optimized door design with better broadband noise reduction. The main conclusions are as follows:

-

1)

The core structure influences the SIP of both the door leaf and the entire door. Specifically, a homogeneous extruded particle board door leaf and a vertical corrugated board door leaf increase the overall SIP by 3 dB. Additionally, the SIP of the door leaf is higher than that of the entire door, with the largest difference reaching up to 9 dB. This shows that the core structure is not the only factor impacting the SIP of wooden doors.

-

2)

The results show that the core structure affects the SIP of wooden doors, but is not the only influence. The theoretical derivation of Gompertz’s rectangular gap sound transmission coefficient indicates that the whole door gap leaks more sound at medium and high frequencies, with the bottom gap leaking more than the side gap. Acoustic finite element modeling of the door leaf reveals that resonance at the intrinsic frequency causes a sound insulation trough. It has been found that the first- and second-order intrinsic frequencies mainly affect the door’s sound insulation. Finally, by optimizing both the door leaf and sealing structures, the SIP of the entire door can be increased to 32 dB, which is 5–8 dB higher than that of traditional designs.

This paper clarifies how the configuration of wooden doors influences their acoustic performance, providing a theoretical basis and technical guidance for improving acoustic design in wooden doors. The findings enhance existing theories in building acoustics and offer practical references for developing high-performance wooden doors, which significantly improve the quality of the built acoustic environment. Future research should explore a wider range of material combinations and structural designs to further increase the SIP and applicability of wooden doors.

Data availability

All data included in this study are available upon request by contact with the third author (Dapeng Xu).

References

Zhao, X. et al. A scalable high-porosity wood for sound absorption and thermal insulation. Nat. Sustain. 6, 306–315 (2023).

Zhang, Z. et al. Seismic performance of new composite concrete block bearing wall with good sound insulation. Constr. Build. Mater. 481, 141648 (2025).

Bader Eddin, M., Ménard, S., Laratte, B. & Wu, T. V. A design methodology incorporating a sound insulation prediction model, life cycle assessment (LCA), and thermal insulation: a comparative study of various cross-laminated timber (CLT) and ribbed CLT-based floor assemblies. Acoustics 6, 1021–1046 (2024).

Buratti, C., Barelli, L. & Moretti, E. Wooden windows: sound insulation evaluation by means of artificial neural networks. Appl. Acoust. 74, 740–745 (2013).

Zhang, Y., Huang, Y., Wang, Z., Li, M. & Adjei, P. Theoretical calculation and test of airborne sound insulation for wooden Building floor. Proc. Institution Civil Eng. - Struct. Build. 176, 515–528 (2023).

Lumnitzer, E., Andrejiova, M. & Yehorova, A. Analysis of the dependence of the apparent sound reduction index on excitation noise parameters.Applied Sciences. 10(23), 8557 (2020).

Fahy, F. Sound and Structural Vibration (Elsevier EBooks, 2007).

Bies, D. A. & Hansen, C. H. Engineering Noise Contril Fourth edn (E and FN Spon, 2009).

Garai, M. & Guidorzi, P. European methodology for testing the airborne sound insulation characteristics of noise barriers in situ: experimental verification and comparison with laboratory data. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 108, 1054–1067 (2000).

Hongisto, V. Sound insulation of doors—part 1: prediction models for structural and leak transmission. J. Sound Vib. 230, 133–148 (2000).

Hao, J., Wu, X., Oporto-Velasquez, G., Wang, J. & Dahle, G. Compression properties and its prediction of wood-based sandwich panels with a novel Taiji honeycomb core. Forests.11(8), 886 (2020).

Hao, J. et al. Deformation and failure behavior of wooden sandwich composites with Taiji honeycomb core under a three-point bending test. Materials. 11(11), 2325 (2018).

Zhao, X. & JIN, M. HU, Y. in The 21st International Conference on Composite Materials. 2.

Ilgın, H. E., Lietzén, J. & Karjalainen, M. An experimental comparison of airborne sound insulation between dovetail massive wooden board and cross-laminated timber elements. Buildings.13(11), 2809 (2023).

Blanchet, P., Perez, C. & Cabral, M. R. Wood Building construction: trends and opportunities in structural and envelope systems. Curr. Rep. 10, 21–38 (2024).

Peliński, K. & Smardzewski, J. Bending behavior of lightweight wood-based sandwich beams with auxetic cellular core. Polymers. 12(8), 1723 (2020).

Fang, B., Chen, L. C., Xu, H., Cai, J. & Li, D. Research on urban road traffic noisecontrol. IOP Conf. Ser. : Earth Environ. Sci. 587, 012110 (2020).

Chuanwen, C., Chenyu, C., Rongping, L. & Philip, S. in Inter-noise and noise-con congress and conference proceedings Vol. 1 1–9 (2014).

Voichita, B. Acoustics of Wood7–36 (Springer Berlin, 1995).

Karlinasari, L., Hermawan, D. & A, M. Sound absorption and sound isolation characteristics of medium-high density wood wool boards from some tropical fast growing species. J. Sci. Technol. For. Prod. 4, 8–13 (2011).

Karlinasari, L. et al. Acoustical properties of particleboards made from Betung bamboo (dendrocalamus asper) as Building construction material. BioResources 7, 5700–5709 (2012).

Mediastika, C. E. Kualitas Akustik panel dinging Berbahan Baku Jerami. Dimensi: J. Archit. Built Environ. 36, 127–134 (2010).

Zulkifli, R., Mohd Nor, M. J., Mat Tahir, M. F., Ismail, A. R. & Nuawi, M. Z. Acoustic properties of multi-Layer Coir fibres sound absorption panel. J. Appl. Sci. 8, 3709–3714 (2008).

Santoni, A., Fausti, P. & Bonfiglio, P. A review of the different approaches to predict the sound transmission loss of Building partitions. Build. Acoust. 27, 253–279 (2020).

ASTM. in Standard Test Method for Laboratory Measurement of Airborne Transmission Loss of Building Partitions and Elements Using Sound Intensity. (2019).

ISO. in. Acoustics Laboratory Measurement of Sound Insulation of Building Elements Part 2: Measurement of Airborne Sound Insulation (ISO, 2021).

Mago, J., Sunali, Negi, A., Bolton, J. S. & Fatima, S. in In Handbook of Vibroacoustics, Noise and Harshness. 1–44 (eds Garg, N.) (Springer Nature Singapore, 2024).

Rafique, F. et al. Designing and experimental validation of single-layer mixed foil resonator acoustic membrane to enhance sound transmission loss (STL) within low to medium frequency range. Appl. Acoust. 219, 109930 (2024).

Kang, C. W., Kim, M. K. & Jang, E. S. An experimental study on the performance of corrugated cardboard as a sustainable sound-absorbing and insulating material. Sustainability. 13(10), 5546 (2021).

Ruello, J. L. A., Pornea, A. G. M., Puguan, J. M. C. & Kim, H. Excellent wideband acoustic absorption of a multifunctional composite fibrous panel with a Dual-Pore network from milled corrugated box wastes. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 4, 654–662 (2022).

Li, S. et al. Sound insulation performance of composite double sandwich panels with periodic arrays of shunted piezoelectric patches. Materials. 15(2), 490 (2022).

Rubáš, P. in INTER-NOISE and NOISE-CON Congress and Conference Proceedings 276–284Institute of Noise Control Engineering, (2017).

Carvalho, F. R., Tiete, J., Touhafi, A. & Steenhaut, K. ABox: new method for evaluating wireless acoustic-sensor networks. Appl. Acoust. 79, 81–91 (2014).

Mengxi, G., Zaisheng, H., Yiqian, Y. & Jiangwei, K. in INTER-NOISE and NOISE-CON Congress and Conference Proceedings Vol. PP 5529–5540Institute of Noise Control Engineering, (2018).

Hongisto, V., KerÄNen, J. & Lindgren, M. Sound insulation of doors—part 2: comparison between measurement results and predictions. J. Sound Vib. 230, 149–170 (2000).

Gompeters, M. C. The sound insulation of circular and slit-shaped apertures. Acta Acust United Acust. 14 (16), 1–16 (1964).

Nolan, M. Experimental characterization of the sound field in a reverberation room. Vol. 145 2237–2246 (2019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

1. Caifeng Long : Conceptualization & Methodology &Writing & Investigation. 2. Xiaochuan Song : Supervision & Project administration. 3. Dapeng Xu : Formal analysis & simulation design. 4. Xu Zhu : Visualization & ValidationAll authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Long, C., Song, X., Xu, D. et al. Frequency domain characterisation of the sound insulation performance of wooden doors and optimal design of high performance wooden doors. Sci Rep 15, 27620 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13223-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13223-9