Abstract

Myocarditis and pericarditis are managed with various treatments, yet prior studies and case reports indicate that certain drug classes may elevate the risk for these inflammatory cardiac conditions. This research aimed to systematically identify the leading drugs most frequently associated with myocarditis and pericarditis cases. Analyses were carried out using the global database of individual case safety reports from 1968 to 2024. We identified the drugs most frequently reported in signal detection with myocarditis and pericarditis, selecting the top 10 drugs based on record count, excluding those used in the treatment of inflammatory cardiac conditions to avoid potential confounding. Two statistical indicators, the information component (IC) with IC025 and reporting odds ratio (ROR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) were used to conduct the disproportionality analysis in this study. The following five drugs were consistently observed with both myocarditis and pericarditis: clozapine, mesalazine, smallpox vaccine, influenza vaccine, and COVID-19 mRNA vaccine. The other leading drugs differed by condition, with nivolumab, pembrolizumab, ipilimumab, valproate, and metronidazole appearing more frequently for myocarditis, and ribavirin, sulfasalazine, methotrexate, omalizumab, and heparin for pericarditis. Each of these drugs showed a significant signal detection with myocarditis (ROR, 83.22 [95% CI, 81.17–85.33]; IC, 3.96 [IC025, 3.94]) and pericarditis (42.16 [41.19–43.16]; 3.66 [3.64]). Although our findings did not allow for causal inference, these findings highlight the importance of monitoring for possible adverse carditis cases when prescribing these drugs. Further studies are encouraged to investigate underlying mechanisms, assess individual patient risk factors, and explore the long-term impacts associated with myocarditis and pericarditis in relation to drug.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Myocarditis and pericarditis are inflammatory conditions of the heart, affecting the myocardium and pericardium, respectively1. These diseases are often caused by infections, commonly viral, autoimmune responses, toxins, or medication hypersensitivity reactions2. Although myocarditis and pericarditis are relatively rare, their impact on health can be profound, ranging from mild symptoms to severe complications, including heart failure, arrhythmias, and even sudden cardiac death3. The global burden of these conditions is difficult to estimate precisely, but they are recognized as significant contributors to cardiovascular morbidity, especially among young adults4. Recent advances in diagnostic techniques have enabled better detection and understanding of these diseases. However, they continue to pose a clinical challenge due to their varied etiologies and potential for life-threatening outcomes5.

Various treatments are employed to manage myocarditis and pericarditis, including anti-inflammatory drugs, immunosuppressants, and, in some cases, antiviral medications5. However, paradoxically, certain medications themselves have been implicated as triggers for myocarditis and pericarditis. Previous studies have reported that specific drug classes, including immunosuppressants, biologics, and vaccines, may be associated with an increased risk of inflammatory cardiac events6,7,8. These findings underscore the importance of meticulous pharmacovigilance to monitor the potential cardiac risks associated with widely used medications. Although previous studies have investigated classes of drugs, a comprehensive analysis focusing on the most frequently related drugs with these specific cardiac conditions has been limited9.

This study aimed to identify the top 10 drugs most frequently associated with reports of myocarditis and pericarditis in a global pharmacovigilance database, to support clinical decision-making and enhance monitoring strategies for potential cardiac-related adverse events.

Methods

Data sources

The primary data source for this study is the global pharmacovigilance database, the world’s largest repository of individual case safety reports (ICSRs)10,11. Since its inception, the database has collected over 35 million reports from more than 140 countries, making it a valuable resource for global pharmacovigilance and drug safety analysis. The Institutional Review Boards of Kyung Hee University approved the use of confidential and electronically processed patient data. Informed consent was waived, as our database does not contain any personally identifiable information.

Selection of cases

For this analysis, we identified reports of myocarditis and pericarditis by searching the global pharmacovigilance database for all ICSRs, using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) version 26.0. Only reports where a drug was classified as “suspect” or “interacting” with myocarditis or pericarditis as an adverse effect were included (Table S1). To reduce indication bias, drugs classified under the cardiovascular system (ATC code CXXXX; e.g., beta blockers, calcium channel blockers, and diuretics), immunosuppressants (ATC code L04XX; e.g., tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitors, interleukin inhibitors, and calcineurin inhibitors), and systemic corticosteroids (ATC code H02AX; e.g., glucocorticoids) were excluded, as these agents are often used in the treatment of inflammatory cardiac conditions12,13,14. Specifically, colchicine (ATC code M04AC) was also excluded from the pericarditis analysis due to its common use in managing this condition15. We then identified the drugs most frequently reported with myocarditis and pericarditis, extracting the top 10 drugs by record count to prevent combination. In addition, to minimize bias resulting from co-prescribed medications, we conducted our analysis focusing solely on drugs that were reported as being individually prescribed.

Data collection

This study utilized ICSRs submitted by various sources, including national pharmacovigilance centers, healthcare professionals, pharmaceutical companies, and patients. The reported data included several key factors: patient demographics (age groups: 0–17, 18–44, 45–64, 65–74, ≥ 75 years, and unknown) and sex, organizational data (reporting years: 1968–1979, 1980–1989, 1990–1999, 2000–2009, 2010–2019, and 2020–2024; reporting regions: Africa, Americas, Southeast Asia, Europe, Eastern Mediterranean, and Western Pacific; and reporter type: health professionals, non-health professionals, and unknown), drug-related information (drug class), and adverse drug reaction data (time to onset [TTO] and outcomes: recovered, not recovered, fatal, and unknown)10.

Statistical analysis

This analysis employed a report-non-report approach to detect the signal of myocarditis and pericarditis with the top 10 most frequently reported drugs using disproportionality analysis. For the disproportionality analysis, we used two key indicators: the information component (IC) and the reporting odds ratio (ROR). The IC was calculated using a Bayesian approach, comparing ADRs to all other drugs in the database. The IC025 value represents the lower limit of a 95% credibility interval for the IC, and a positive IC025 value (IC025 > 0.00) is considered statistically significant. The ROR was derived from a contingency table analysis, and a significant signal detection between adverse events and a drug is established when both the ROR and its lower 95% confidence interval (CI) are greater than 1.00. A two-sided p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, and all analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.4; SAS Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Overall analysis

Between 1968 and 2024, the global pharmacovigilance database identified over 35 million ICSRs, resulting in 8,293,350 reports of myocarditis and 8,631,131 reports of pericarditis (Fig. 1). For analysis, we selected the 10 most frequently reported drugs associated with each condition, resulting in 35,017 myocarditis reports and 24,959 pericarditis reports (Table 1). A majority of reports occurred in males, with 66.84% for myocarditis and 53.38% for pericarditis. The age group of 18–44 years accounted for 44.34% of myocarditis reports and 39.88% of pericarditis reports. Approximately half of the reports were captured in the Americas (51.59% for myocarditis and 48.92% for pericarditis), followed by Europe (33.89% and 34.64%, respectively) and the Western Pacific region (14.22% and 16.23%, respectively). Figures S1 and S2 illustrate the cumulative reports over time, showing a steady increase in myocarditis and pericarditis over the past five decades. Notably, there was a sharp rise in 2021, coinciding with the introduction of the COVID-19 mRNA vaccines and the occurrence of acute SARS-CoV-2 infections.

Proportional distribution and stratified analysis of myocarditis and pericarditis associated with top 10 drugs

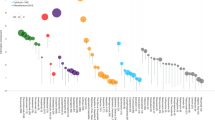

Figure 2 illustrates the proportional distribution of the 10 most frequently reported drugs associated with myocarditis and pericarditis. Among these, five drugs were identified as commonly linked to both conditions: clozapine, mesalazine, smallpox, influenza, and COVID-19 mRNA vaccine. However, the remaining five drugs differed for each condition, with nivolumab, pembrolizumab, ipilimumab, valproate, and metronidazole identified in cases of myocarditis, and ribavirin, sulfasalazine, methotrexate, omalizumab, and heparin in cases of pericarditis. Across all age groups and sexes, significant signal detection was observed for both carditis subtypes. Notably, the highest IC values were found in the 0 to 17 years age group (myocarditis: IC, 4.57; IC025, 4.51 and pericarditis: IC, 4.33; IC025, 4.23), indicating a significant signal detection for both conditions in younger individuals. For myocarditis, males exhibited a higher ROR (105.12; 95% CI, 101.71 to 108.65) compared to females (ROR, 59.11; 95% CI, 56.86 to 61.45), consistent with a greater number of reports in males (23,407/35,017 reports; 66.84%). In contrast, pericarditis showed less pronounced differences between males (ROR, 48.12; 95% CI, 46.56 to 49.73) and females (ROR, 37.32; 95% CI, 36.10 to 38.58), consistent with a relatively similar number of reports in males (13,500/24,959; 54.09%) (Tables S2 and S3). A sensitivity analysis excluding COVID-19 vaccine reports showed consistent patterns in subgroup analyses of drug-associated myocarditis and pericarditis (Tables S4 and S5). Similarly, when restricted to reports submitted exclusively by healthcare professionals, the sensitivity analysis revealed consistent patterns across subgroups (Tables S6 and S7).

Disproportionality analysis of myocarditis and pericarditis associated with the top 10 drugs

Among the identified drugs, the COVID-19 mRNA vaccine accounted for the largest proportion of myocarditis (76.16%; 26,670/35,017), followed by clozapine (15.29%; 5,353/35,017). Similarly, in the report of pericarditis, the COVID-19 mRNA vaccine also represented the highest proportion of reports (88.15%; 22,001/24,959). However, unlike myocarditis, no other drug accounted for more than 10% of total pericarditis reports, with clozapine being the drug with the second highest proportion of reports (2.88%; 718/24,959). With the disproportionality analysis, all drugs except metronidazole showed significant signal detection for myocarditis, while all 10 drugs showed a significant signal detection for pericarditis (Figs. 3 and 4). Among the reports, smallpox vaccine exhibited the highest ROR for both myocarditis (103.62 [95% CI, 92.53 to 116.05]) and pericarditis (111.93 [99.34 to 126.13]). In contrast, while the COVID-19 mRNA vaccine contributed the largest number of both carditis reports, it showed relatively lower RORs for myocarditis (38.30 [37.34 to 39.29]) and pericarditis (55.95 [54.16 to 57.80]). Notably, despite the higher number of reports with the COVID-19 mRNA vaccine, the highest IC values were observed with the smallpox vaccine (myocarditis: IC, 6.43; IC025, 6.24; pericarditis: IC, 6.50; IC025, 6.31), indicating a significant signal detection between the smallpox vaccine and both carditis subtypes.

Clinical features of myocarditis and pericarditis in cases with the top 10 drugs

A detailed description of each drug for both conditions is provided in Tables S8 and S9. For both carditis types, all of the top 10 drugs had a median TTO of 1 day. For myocarditis, the mean TTO was 9.52 days (standard deviation, 62.68), and for pericarditis, it was 6.46 days (standard deviation, 44.78). Most reports, excluding those with unknown outcomes, resulted in recovery, comprising 66.62% of known myocarditis outcomes and 63.04% of known pericarditis outcomes. Among reports with fatal outcomes, three monoclonal antibodies (pembrolizumab, ipilimumab, and nivolumab) showed nearly 20% of fatalities in myocarditis reports, while other drugs showed to a fatality rate of less than 10%. In the report of pericarditis, only sulfasalazine showed a greater than 10% fatality rate. Outside of cardiac-related events, the most frequent concurrent adverse events for myocarditis-inducing drugs were related to the muscular system, with over 20% of such events reported for the three monoclonal antibody drugs (ipilimumab, nivolumab, and pembrolizumab). In contrast, for pericarditis-inducing drugs, the most common concurrent adverse events outside of the cardiac system were neurologic events, with three vaccines (smallpox, influenza, and COVID-19 mRNA vaccine) showing over 14% of each report. These three vaccine types were also showed concurrent neurologic adverse events more than 17% in the myocarditis reports.

Discussion

Key findings

This study offers a comprehensive overview of myocarditis and pericarditis, focusing on reports of these events received by the global pharmacovigilance database. The signal of five drugs (clozapine, mesalazine, smallpox vaccine, influenza vaccine, and COVID-19 mRNA vaccine) was detected with both myocarditis and pericarditis, while five other drugs were distinct for each condition: nivolumab, pembrolizumab, ipilimumab, valproate, and metronidazole for myocarditis, and ribavirin, sulfasalazine, methotrexate, omalizumab, and heparin for pericarditis. Cumulative reports indicated a steady rise in both carditis, with a sharp increase in 2021 following the introduction of COVID-19 vaccines. In both conditions, the COVID-19 mRNA vaccine accounted for the largest proportion of reports, with 76.16% for myocarditis and 88.15% for pericarditis. Among these drugs, all nine drugs except metronidazole showed a significant signal detection with myocarditis, while all ten drugs showed significant signal detection with pericarditis. Among them, three monoclonal antibody drugs (ipilimumab, nivolumab, and pembrolizumab) were linked to nearly 20% of fatal outcomes in myocarditis, while only sulfasalazine exceeded a 10% fatality rate in pericarditis. Additionally, in the myocarditis reports, the monoclonal antibody drugs (ipilimumab, nivolumab, and pembrolizumab) showed a higher rate of concurrent muscular system disorders. In contrast, in the pericarditis reports, three vaccines (smallpox, influenza, and COVID-19 mRNA vaccine) showed a higher rate of concurrent neurologic disorders.

Plausible underlying mechanisms

Building on previous studies that established a significant signal detection between COVID-19 vaccines and both types of carditis, this study also found the COVID-19 mRNA vaccine to be the most frequently reported drug for myocarditis and pericarditis16. Due to its mechanism, the COVID-19 mRNA vaccine may act as an external antigen17. This effect can be explained by molecular mimicry, as the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2, which is the target of COVID-19 vaccines, shares structural similarities with cardiac proteins such as myosin heavy chain or troponin C1. This similarity may lead to cross-reactivity and inflammation in the heart muscle18. Additionally, since SARS-CoV-2 can directly infect cardiac cells through the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor and cause cardiac injury, the immune response triggered against the spike protein after vaccination might indirectly imitate this process, leading to inflammation in the heart muscle or surrounding tissue19.

Furthermore, several issues related to COVID-19 mRNA vaccines may have influenced the results. First, myocarditis has been widely publicized as a potential adverse effect of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines, which may have led to stimulated reporting driven by heightened public awareness and extensive media coverage20. Second, the unprecedented scale of global vaccination campaigns resulted in a large number of individuals being exposed to these vaccines, naturally increasing the volume of reported events21. Third, it is important to acknowledge that SARS-CoV-2 infection itself is a recognized risk factor for myocarditis. In some cases, the reported events may have been attributable to concurrent or recent infection rather than the vaccine22. In our analysis, the high volume of reports associated with COVID-19 mRNA vaccines likely reflects both the widespread exposure and potential reporting bias, rather than an inherently stronger safety signal. This bias may also influence other aspects of the data. For instance, the median TTO for myocarditis was observed to be just 1 day—substantially shorter than what has been documented in clinical settings—which may suggest heightened vigilance and prompt reporting among vaccine recipients. Furthermore, we could not completely exclude the possibility of coexisting or recent SARS-CoV-2 infection in these cases, which limits the ability to attribute causality solely to the vaccine.

Clinical and policy implications

Policy frameworks should incorporate comprehensive risk-benefit analyses, especially for populations identified as having a higher risk of vaccine-associated myocarditis and pericarditis, such as young males17,23. Tailoring vaccination schedules, including dosing intervals and vaccine type considerations, may optimize safety profiles. For instance, extending the interval between doses has been associated with a reduced risk of myocarditis24.

Especially, in the case of the observed higher signal detection between COVID-19 mRNA vaccines and increased reports of myocarditis and pericarditis, it suggests a nuanced approach to vaccination strategies. Although these adverse events warrant careful attention, the benefits of vaccination in preventing severe COVID-19 outcomes remain significant25.

For clinicians, these findings suggest the need for heightened awareness of potential cardiac adverse events following vaccination or drug administration, especially in at-risk populations26. Furthermore, early detection and appropriate treatment are crucial to mitigate complications associated with these conditions27.

Strengths and limitations

Although this study included several strengths, it also has limitations, primarily due to the nature of the database. Our database relies on spontaneous reporting, meaning not all adverse events are captured, which may lead to inconsistencies in case definitions. Since standardized diagnostic criteria are not mandatory in such reports, some reports may be misclassified or may reflect conditions other than myocarditis or pericarditis. Furthermore, some reports may be either underreported or overreported, depending on factors such as public awareness, media attention, and clinical suspicion28. For instance, the low proportion of fatal outcomes could be influenced by underreporting, as these reports may be less frequently documented. In addition, unlike electronic medical records, which provide systematically recorded clinical timelines, pharmacovigilance data rely on spontaneous self-reporting. As a result, the accuracy of TTO may be compromised due to recall bias or incomplete information, potentially affecting the interpretation of TTO-related findings in our study. This likely reflects a tendency to report events occurring soon after drug exposure. However, the large scale of the dataset provides valuable insights into global trends and rare adverse events that smaller studies may not detect29. In this context, despite the potential for underreporting, the patterns observed in the global pharmacovigilance database offer a strong foundation for further investigation into drug-associated myocarditis and pericarditis. Second, this study did not include variables such as concomitant medications and underlying health conditions, which could influence the occurrence of adverse events30. Although this limitation may introduce potential biases, the large and diverse dataset, combined with suitable statistical adjustments, helps to mitigate these effects. Third, establishing a direct causal link between medications and adverse carditis events is challenging due to the observational nature of the data and the lack of detailed clinical information31. Furthermore, the term “associated with” is employed to reflect observed trends within the database and is not intended to suggest a confirmed causal relationship. Fourth, there is a clinical overlap between myocarditis and pericarditis, as myocarditis can occasionally occur as a complication of pericarditis. To clearly distinguish the two conditions, we used the MedDRA system, a widely accepted and standardized medical terminology framework. To ensure diagnostic specificity, reports coded as perimyocarditis, which represent overlapping features of both conditions, were excluded from our analysis. Nonetheless, the use of MedDRA terms may introduce diagnostic misclassification, as these codes rely on the spontaneous report of the reporter rather than clinically validated diagnoses. This should be considered when interpreting disease-specific findings. Although some diagnostic uncertainty may exist, particularly in fatal reports lacking histological confirmation, the predominance of reports submitted by healthcare professionals likely enhances the reliability of case classification. This should be considered when interpreting disease-specific findings. Last, we reported only the top 10 drugs reported for each condition. However, the absence of a drug from a condition’s top 10 list does not imply its lack of signal. For example, metronidazole appeared among the top 10 for myocarditis but may also have meaningful signal with pericarditis that were not captured due to ranking thresholds.

Conclusion

Although our findings did not allow for causal inference, this study is the first to identify the 10 most frequently reported drugs associated with myocarditis and pericarditis using the extensive, long-term pharmacovigilance data from the global pharmacovigilance database. The findings suggest a notable signal detection between several vaccine types (smallpox, influenza, and COVID-19 mRNA vaccine) and both forms of carditis. Notably, the COVID-19 mRNA vaccine had the highest number of reports, underscoring the imperative for heightened clinical vigilance in monitoring potential carditis manifestations following administration of these drugs. Future studies should build on these results by investigating the underlying mechanisms, exploring patient-specific risk factors, and examining the long-term outcomes for these drug-associated carditis events.

Data availability

Data are available on reasonable request. Study protocol, statistical code: available from DKY (email: yonkkang@gmail.com). Data set: available from the Uppsala Monitoring Centre or World Health Organization through a data use agreement.

References

Caforio, A. L. et al. Current state of knowledge on aetiology, diagnosis, management, and therapy of myocarditis: a position statement of the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Myocardial and Pericardial Diseases. Eur Heart J https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/eht210 (2013).

Cremer, P. C., Klein, A. L., Imazio, M. & Diagnosis Risk stratification, and treatment of pericarditis: A review. Jama 332, 1090–1100. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2024.12935 (2024).

Heymans, S., Van Linthout, S., Kraus, S. M., Cooper, L. T. & Ntusi, N. A. B. Clinical characteristics and mechanisms of acute myocarditis. Circ. Res. 135, 397–411. https://doi.org/10.1161/circresaha.124.324674 (2024).

Mensah, G. A., Fuster, V., Murray, C. J. L. & Roth, G. A. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risks, 1990–2022. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 82, 2350–2473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2023.11.007 (2023).

Martens, P., Cooper, L. T. & Tang, W. H. W. Diagnostic approach for suspected acute myocarditis: considerations for standardization and broadening clinical spectrum. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 12, e031454. https://doi.org/10.1161/jaha.123.031454 (2023).

Lampejo, T. Caution with the use of NSAIDs in myocarditis. Qjm 116, 153. https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcac073 (2023).

Semenzato, L. et al. Long-Term prognosis of patients with myocarditis attributed to COVID-19 mRNA vaccination, SARS-CoV-2 infection, or conventional etiologies. Jama 332, 1367–1377. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2024.16380 (2024).

Law, Y. M. et al. Diagnosis and Management of Myocarditis in Children: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 144, e123–e135. https://doi.org/10.1161/cir.0000000000001001 (2021).

Xia, Y. et al. Treatment adherence to disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in Chinese patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Patient Prefer Adherence. 10, 735–742. https://doi.org/10.2147/ppa.S98034 (2016).

Cho, J. et al. Global estimates of reported Vaccine-Associated ischemic stroke for 1969–2023: A comprehensive analysis of the world health organization global pharmacovigilance database. J. Stroke. https://doi.org/10.5853/jos.2024.01536 (2024).

Jeong, J., Jo, H., Park, J., Rahmati, M. & Pizzol, D. Regional burden of vaccine-associated menstrual disorders and sexual dysfunction: a retrospective study. Life Cycle. 4, e12. https://doi.org/10.54724/lc.2024.e12 (2024).

Nguyen, L. S. et al. Systematic analysis of drug-associated myocarditis reported in the world health organization pharmacovigilance database. Nat. Commun. 13, 25. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-27631-8 (2022).

Cong, L. et al. Use of cardiovascular drugs for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease among Rural-Dwelling older Chinese adults. Front. Pharmacol. 11, 608136. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2020.608136 (2020).

Ammirati, E. et al. Management of Acute Myocarditis and Chronic Inflammatory Cardiomyopathy: An Expert Consensus Document. CircHeartFail 13, e007405. https://doi.org/10.1161/circheartfailure.120.007405 (2020).

Chiabrando, J. G. et al. Management of acute and recurrent pericarditis: JACC State-of-the-Art review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 75, 76–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2019.11.021 (2020).

Jain, S. S. et al. Cardiac manifestations and outcomes of COVID-19 vaccine-associated myocarditis in the young in the USA: longitudinal results from the myocarditis after COVID vaccination (MACiV) multicenter study. EClinicalMedicine 76, 102809. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2024.102809 (2024).

Lee, S. et al. Global estimates on the reports of vaccine-associated myocarditis and pericarditis from 1969 to 2023: findings with critical reanalysis from the WHO pharmacovigilance database. J. Med. Virol. 96, e29693. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.29693 (2024).

Heidecker, B. et al. Myocarditis following COVID-19 vaccine: incidence, presentation, diagnosis, pathophysiology, therapy, and outcomes put into perspective. A clinical consensus document supported by the heart failure association of the European society of cardiology (ESC) and the ESC working group on myocardial and pericardial diseases. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 24, 2000–2018. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejhf.2669 (2022).

Nishiga, M., Wang, D. W., Han, Y., Lewis, D. B. & Wu, J. C. COVID-19 and cardiovascular disease: from basic mechanisms to clinical perspectives. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 17, 543–558. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-020-0413-9 (2020).

Bozkurt, B., Kamat, I., Hotez, P. J. & Myocarditis With COVID-19 mRNA vaccines. Circulation 144, 471–484. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.121.056135 (2021).

Almadani, O. A. & Alshammari, T. M. Vaccine adverse event reporting system (VAERS): evaluation of 31 years of reports and pandemics’ impact. Saudi Pharm. J. 30, 1725–1735. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsps.2022.10.001 (2022).

Patone, M. et al. Risk of myocarditis after sequential doses of COVID-19 vaccine and SARS-CoV-2 infection by age and sex. Circulation 146, 743–754. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.122.059970 (2022).

Witberg, G. et al. Myocarditis after Covid-19 vaccination in a large health care organization. N Engl. J. Med. 385, 2132–2139. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2110737 (2021).

Le Vu, S. et al. Influence of mRNA Covid-19 vaccine dosing interval on the risk of myocarditis. Nat. Commun. 15, 7745. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-52038-6 (2024).

Copland, E. et al. Safety outcomes following COVID-19 vaccination and infection in 5.1 million children in England. Nat. Commun. 15, 3822. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-47745-z (2024).

Araja, D., Krumina, A., Nora-Krukle, Z., Berkis, U. & Murovska, M. Vaccine Vigilance System: Considerations on the Effectiveness of Vigilance Data Use in COVID-19 Vaccination. Vaccines (Basel) 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10122115 (2022).

Klein, N. P. et al. Surveillance for adverse events after COVID-19 mRNA vaccination. Jama 326, 1390–1399. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.15072 (2021).

Oh, J. et al. Global burden of vaccine-associated uveitis and their related vaccines, 1967–2023. Br. J. Ophthalmol. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo-2024-325985 (2024).

Chandler, R. E. et al. Current safety concerns with human papillomavirus vaccine: A cluster analysis of reports in VigiBase(®). Drug Saf. 40, 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-016-0456-3 (2017).

Kim, T. H. et al. Association between glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and risk of suicidality: A comprehensive analysis of the global pharmacovigilance database. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 26, 5183–5191. https://doi.org/10.1111/dom.15864 (2024).

Raschi, E., Bianchin, M., Ageno, W., De Ponti, R. & De Ponti, F. Adverse events associated with the use of direct-acting oral anticoagulants in clinical practice: beyond bleeding complications. Pol. Arch. Med. Wewn. 126, 552–561. https://doi.org/10.20452/pamw.3529 (2016).

Acknowledgements

The licensing agreement in our database was valid until February 7, 2025 (VigiBase). The perspectives presented herein do not reflect the views of the Uppsala Monitoring Centre or the World Health Organization. We acknowledge that some terms and statements in this manuscript (‘association’ or ‘drug-associated’) may be interpreted as implying causality or formal clinical guidance, which was not intended. The dataset is derived from a spontaneous reporting system and disproportionality analysis and therefore does not permit the estimation of incidence or prevalence. This discussion represents the authors’ interpretative perspectives rather than conclusions directly drawn from the database. Therefore, the findings should be approached with caution and are not intended to guide clinical decision-making. The terms ‘drug-associated myocarditis’ and 'drug-associated pericarditis emerged from a disproportionality analysis, which does not establish a causal relationship. Given that the primary aim of this study was signal detection, careful interpretation of the terminology used is essential.

Funding

This research was supported by grants from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Korea government (RS-2024-00441114) and the Institute of Information & Communications Technology Planning & Evaluation (IITP) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (RS-2024-00509257, Global AI Frontier Lab), and Global Physician-scientist program funded by the Ministry of Health and Welfare of Korea (RS-2024-00405141). The funders had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dr. Dong Keon Yon had full access to all data in the study and took responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript before submission. Study concept and design: JC, JP, HJ, and DKY; acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: JC, JP, HJ, and DKY; drafting of the manuscript: JC, JP, HJ, and DKY; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors; statistical analysis: JC, JP, HJ, and DKY; study supervision: DKY. DKY supervised the study and served as the guarantor. JC, HJ, and JP contributed equally as first authors. JMY and DKY contributed as corresponding authors. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet the authorship criteria, and that no one meeting the criteria has been omitted.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Approval for using confidential and electronically processed patient data was granted by the institutional review board of Kyung Hee University. The requirement for written consent was waived by the ethics committee owing to the population-level data set.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cho, J., Jo, H., Park, J. et al. Top 10 drugs most frequently associated with adverse events of myocarditis and pericarditis. Sci Rep 15, 28849 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13234-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13234-6