Abstract

Maintaining physical function and mobility is essential for older adults to preserve independence, reduce fall risk, and minimise dependence on care. “Power Centering for Seniors” (PCS) is a mindfulness-based, proprioceptive training programme combining Tai Chi and Qi Gong with functional strength and balance practices. This study assessed the efficacy of the PCS programme on physical functional performance in older community-dwelling adults. The study included 57 participants aged 70 years or older, randomised into an intervention group (IG) or a control group (CG). The PCS intervention consisted of 24 supervised sessions over 12 weeks, with additional home exercises. Physical functional performance was measured using the Continuous Scale Physical Functional Performance 10 (CS-PFP-10) test, focusing on the subdomain Lower Body Strength and Balance & Coordination. A linear mixed-effects model was used to analyse the data, adjusting for baseline CS-PFP-10 scores, sex, and age. Fifty-one participants completed the study. The PCS intervention led to non-significant improvements in the CS-PFP-10 total score compared to the CG, with an adjusted difference of 2.05 points (95% CI: −0.78 to 4.89; p = 0.163; Cohen’s d = 0.403). Similar trends were observed in the sub-scores for Lower Body Strength (adjusted difference: 2.84, 95% CI: −0.21 to 5.90; p = 0.074; Cohen’s d = 0.517) and Balance & Coordination (adjusted difference: 3.34, 95% CI: −0.09 to 6.79; p = 0.063; Cohen’s d = 0.541). The PCS intervention showed potential for improving physical function in older adults in areas critical for maintaining mobility and independence. While trends were favourable, the results did not reach statistical significance.

Trial registration ClinicalTrials.gov NCT04861831; date of registration: April 27, 2021.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Maintaining physical functional capacities and mobility is crucial for older adults to preserve independence and continue living at home1. Physical decline can lead to restrictions in basic daily tasks, which can pose a risk for dependence on care and assistance2. Physical inactivity and loss of physical function are major socio-economic burdens on healthcare systems and present a significant public health challenge, particularly in light of the projected increase in the ageing population3. The World Health Organisation (WHO) recommends maintaining physical function as a key public health strategy4. However, preventive strategies for physical functional decline are not sufficiently implemented, highlighting the need for multidisciplinary, multicomponent exercise programmes tailored to the ageing population5.

The “Power Centering for Seniors” (PCS) training is grounded in key Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) concepts. The Yin-Yang framework underlies Tai Chi (Tai Ji)—emphasizing harmony between complementary opposites (e.g., stillness vs. motion; inhalation vs. exhalation)—by alternating “closing” and “opening” movements to achieve a dynamic mind–body equilibrium7. Qi Gong, a meditative movement practice integrating body, breath, and mind to cultivate life energy, and Tai Chi—characterised by slow, flowing sequences, structural alignment, and mindful breathing—are thus incorporated into the PCS programme to harmonise neuromuscular and energetic processes7,8,9. The PCS training is a mindfulness-based and proprioceptive balance training programme designed to enhance physical function, mobility in daily activities, and quality of life while also reducing the fall risk. PCS integrates Western flexibility- and strength-challenging exercises with cognitive dual-tasking elements derived from Qi Gong and Tai Chi. The programme emphasises “centring”, encouraging participants to reflect on their perceived mobility to foster empowerment and motivation to maintain or improve function. The exercises progress in intensity through four rounds of six modules each, and in the second half, participants compile an individualised “at-home” version of the programme, integrating this functionality-based training into their daily life.

Physical functional capacities and mobility can be measured by various validated and standardised performance tests, such as the Timed Up and Go (TUG) test10 or the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB)11. This study aimed to investigate the effect of the PCS intervention on the level of functional performance in daily activities using the Continuous Scale Physical Functional Performance 10 (CS-PFP-10) test. Unlike more narrowly focused assessments, the CS-PFP-10 encompasses multiple dimensions of physical function, providing a comprehensive evaluation of an individual’s ability to perform everyday tasks. The primary focus was on improvements in Lower Body Strength and Balance & Coordination subdomains.

Methods

Study design

This study is a secondary analysis of the larger PCS study conducted at the University Department of Geriatric Medicine FELIX PLATTER in Basel, Switzerland. The PCS study was originally designed as a monocentric, single-blinded (i.e. the assessors of the study outcomes were blinded), crossover randomised controlled trial (RCT) to evaluate the effects of the “Power Centering for Seniors” (PCS) intervention on various aspects of physical functionality and quality of life in older adults. However, due to COVID-19 lockdown restrictions, the crossover phase could not be executed as planned. Consequently, we compared the intervention and control groups following the standard RCT approach.

Participants

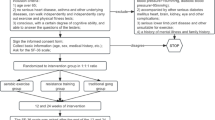

Between the beginning of January 2021 and the end of February 2021, community-dwelling older adults were recruited for the study through advertisements in local newspapers, information sessions at senior centres, and flyers distributed to post boxes. Eligible participants were aged 70 years or older, had a habitual walking speed between 80 and100 cm/s (assessed with the 4-m walking test), and were able to walk at least 15 m independently, with or without walking aids but without human assistance12,13. Exclusion criteria included severe neurologic or musculoskeletal conditions affecting mobility (e.g., advanced Parkinson’s disease, hemiplegia), clinically significant comorbidities (e.g., severe cardiovascular disease, chronic pulmonary disease), recent fractures (i.e. in the last 3 months), visual impairment, terminal illness, cognitive impairment with a Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) score below 18, and participation in another clinical trial. Individuals who had previously participated in the PCS programme were also excluded. There were no couples (i.e. both individuals) participating in the study.

Eligibility was initially determined through telephone screening, conducted by trained staff using a structured questionnaire based on our predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. This screening involved standardised questions regarding participants’ mobility, health status, and relevant medical history.

Sample size and power calculation

The sample size was determined based on usual gait speed, the primary outcome of the parent study. Based on the sample size calculation of the parent study, 57 participants were required to detect a significant effect. Given the exploratory nature of this secondary analysis, a post hoc power calculation was conducted for the CS-PFP-10 Balance & Coordination sub-score, which was expected to show the greatest improvement due to the intervention’s focus. With a total sample size of 57, the study had a power of 60.7% to detect a difference of approximately 3 points (assuming a standard deviation of 5.8 and a significance level of 5%), corresponding roughly to a medium effect size (Cohen’s d ≈ 0.5). Hence, in this explorative study, effect sizes are prioritised above statistical significances.

Randomisation and blinding

Participants were randomly assigned to either the intervention group (IG) or the control group (CG) following a block randomisation procedure with varying block sizes of 4, 6, or 8. Randomisation was performed immediately after the screening visit. Due to the nature of the intervention, blinding of participants and the assessment team was not feasible. However, the intervention team was not involved in the assessment and data analysis to minimise bias.

Intervention

The PCS intervention is a supervised, multicomponent group-exercise programme, specifically designed for older adults (see Online Supplementary Material 1 for a description of the PCS intervention). The maximum group size in the study was 15 participants. It combines Western practices of flexibility and strength exercises with cognitive dual-tasking elements drawn from Qi Gong and Tai Chi. The programme aims to improve physical function, mobility, and quality of life while reducing fall risk. The intervention included 24 sessions over 12 weeks, with each session lasting 75 min. Participants were encouraged to practice additional home exercises for approximately 40 min, three times per week. These home exercises were individualised during the programme and incorporated functional tasks relevant to daily life. Adherence to both the group sessions and home exercises was monitored through participant diaries, which were regularly reviewed by instructors.

Control group

Participants in the CG did not receive any specific intervention during the 12-week study period but were offered the PCS programme after the trial’s completion. They were asked to maintain their usual activities and received the same assessments as the IG.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of the PCS study was normal walking speed, with the sample size calculated accordingly. The current analysis focuses on a secondary outcome, the change in physical functional performance as measured by the Continuous Scale Physical Functional Performance 10 (CS-PFP-10) test14,15,16. The CS-PFP-10 is a validated and reliable tool that quantifies physical performance across ten standardised daily activities (Table 1), yielding a total score (0–100 points) and sub-scores in five domains17: Upper Body Strength, Upper Body Flexibility, Lower Body Strength, Balance & Coordination, and Endurance. Higher scores indicate better physical function18, with the total score providing a comprehensive measure of functional independence. We selected this test because it reflects the functional challenges of daily-life mobility in doing things around the house and accessing socio-cultural life19,20. We used the validated German version of the CS-PFP-10 test16. The CS-PFP-10 set-up at our facility is illustrated in Supplementary Material 1.

Data collection and assessments

Data collection took place between April and July 2021. Baseline assessments were conducted one week before the intervention started for the IG and at a similar time point for the CG. Post-intervention assessments were completed after the 12-week intervention period. All assessments were performed at the certified CS-PFP-10 laboratory of the Basel Mobility Center under standardised conditions16. Participants were instructed to perform each task at their maximum effort while remaining within their comfort and safety limits. Physical performance assessments (including the CS-PFP-10 and SPPB) were conducted with participants wearing their normal shoes (preferably the same ones at both tests) to ensure consistency. This approach helped maintain standardisation across measurements. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) was administered in a quiet, controlled environment at our research facility to ensure standardised testing conditions.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics were described using means and standard deviations for continuous variables or frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Analyses were conducted according to the groups as initially randomised. The primary analysis compared changes in the CS-PFP-10 total score and sub-scores from pre- to post-intervention between the IG and CG using a linear mixed-effects model. The model included group allocation as the primary predictor and adjusted for baseline CS-PFP-10 scores, sex, and age. The recruitment wave was treated as a random effect to account for potential intra-group correlations. Model assumptions were checked by examining the residuals. All analyses were conducted using R version 3.4.4 or higher, with the nlme package used for fitting the linear mixed models21.

Prior to the analysis, we conducted relevant assumption checks: First, the normality of residuals was assessed using QQ plots, which indicated that the residuals were approximately normally distributed across all outcome variables. Homoscedasticity was evaluated by plotting residuals against fitted values, revealing no apparent pattern and supporting the assumption of constant variance. Multicollinearity was examined using Variance Inflation Factors (VIF), with all predictors showing VIF values close to 1, indicating no significant multicollinearity. Overall, these diagnostics suggest that the assumptions underlying the linear mixed-effects models were reasonably met, allowing for valid inference from the models.

Adverse events

Adverse events, including falls and serious adverse events (SAEs), were monitored throughout the study. Falls were recorded during the live classes, and any injuries were documented. SAEs were assessed by an independent committee to determine whether they were related to the intervention.

Also, during home-based exercises, safety was closely monitored throughout the intervention. Specifically, during the first 12 sessions, participants were provided with detailed instructions on the home-based exercises (as outlined in Online Supplementary Material 1). At the end of each class, instructors reviewed the prescribed homework with participants, ensuring that everyone clearly understood how to perform the exercises safely at home. Participants then completed homework diaries in which they recorded the duration of their exercise, any adverse effects (e.g., muscle soreness, headaches, shortness of breath), and other relevant observations. These completed sheets were submitted and reviewed at the beginning of the subsequent class by a certified instructor, who also inquired about the participants’ experiences. Any adverse events reported were promptly documented and communicated to the research team for further evaluation. This systematic approach ensured continuous monitoring of safety during home practice.

Results

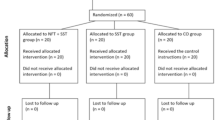

The study included 57 participants who were randomly assigned to the intervention group (IG) or the control group (CG). Of the 57 participants, 29 were allocated to the IG and 28 to the CG. During the study, 6 participants dropped out (3 from each group), resulting in 51 participants completing the study (26 in the IG and 25 in the CG). The flow of participants is shown in Fig. 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were similar between the two groups, as shown in Table 2. The mean age was 79.3 years (SD 4.6) in the IG and 81.4 years (SD 5.2) in the CG. Both groups had a similar sex distribution, with 27.6% male and 72.4% female participants in the IG, and 39.3% male and 60.7% female in the CG. The average Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) score was comparable between the groups (IG: 26.9, CG: 26.9), indicating similar cognitive functioning at baseline. Other characteristics, including body mass index (BMI), history of falls, comorbidities, and physical activity levels, were also well-matched between groups (Table 2).

In the analysis of the intervention effects on physical function outcomes, the adjusted differences between the intervention and control groups were generally positive across most outcomes, though none reached statistical significance at the conventional alpha level (Table 3). The total physical function score and specific subdomains, such as Lower Body Strength and Balance & Coordination, showed trends favouring the intervention group, with p-values approaching significance. However, confidence intervals for all outcomes included zero, suggesting uncertainty in these estimates. Effect sizes for the outcomes indicated small to moderate effects, particularly in Lower Body Strength and Balance & Coordination. These results suggest a potential positive effect of the intervention, but further research with a larger sample size may be needed to confirm these findings.

Regarding adverse events, two falls were recorded during live classes in the IG, but no injuries were reported. Serious adverse events (SAEs) occurred in one participant in the IG and six in the CG, including hospitalisations due to conditions such as diverticulitis and prostate biopsy. These SAEs were reviewed and deemed unrelated to the intervention.

Discussion

This randomised controlled trial is the first to investigate the efficacy of the “Power Centering for Seniors” (PCS) intervention on physical functional performance in daily life activities among older community-dwelling adults. In summary, the PCS intervention showed promising but statistically non-significant trends in improving the CS-PFP-10 total score and key subdomains (Lower Body Strength, Balance & Coordination, and Endurance), with effect sizes (Cohen’s d) ranging from small to medium. In addition to the positive effects, we observed a statistically non-significant reduction in the Upper Body Strength domain (Cohen’s d = −0.338). Larger studies could enhance statistical power, reduce variability, and provide a clearer demonstration of the PCS programme’s potential benefits.

Comparison with existing literature

The findings of this study are consistent with a body of research that underscores the efficacy of multifaceted exercise programmes in improving physical functional performance in older adults. Programmes that incorporate balance, strength, and flexibility training, such as the PCS intervention, are particularly effective in addressing the decline in mobility and the increased risk of falls associated with ageing. For instance, it is recommended that older adults engage in a minimum of 3 h per week of balance-challenging exercises, including walking and strength training, to mitigate the risk of falls22.

Qi Gong and Tai Chi, which are integral components of the PCS programme, have been shown to have positive effects on strength, balance, and posture, as well as on social support networks among older adults23,24,25,26. Compared to inactive controls, the observed effect sizes in our study align with meta-analytical findings from yoga interventions (e.g., balance: Hedges’ g = 0.7; lower body flexibility: g = 0.5; lower body strength: g = 0.45)27.

Further meta-analytical evidence indicates that specific resistance training can achieve large effects on muscle strength in very elderly (above 75 years of age) individuals (e.g., Cohen’s d = 0.97)28. These effects are notably greater than those we observed in our multicomponent PCS programme, which targets a broader range of functional domains at the expense of maximal gains in single domains like muscle strength. This underscores the potential benefits of tailored resistance training for individuals with a primary goal of improving muscle strength.

Group-based exercise programmes, like the PCS intervention, have also been proven effective in improving functional capacities in the elderly, particularly when they are multicomponent in nature29,30. The combination of group exercises with home-based exercises, goal setting, empowerment, and participant engagement has been shown to enhance the effectiveness of such interventions31,32. Moreover, regular monitoring, tailored adjustments, and supervision, all of which are integral to the PCS programme, are essential for ensuring that the intervention meets the specific needs of each participant and maximises its benefits.

These practices also have documented benefits for psychological well-being and general health outcomes33. The inclusion of these elements in the PCS programme may contribute to the observed improvements in coordination and lower body function by promoting better body awareness, control, and mental focus, which are crucial for maintaining mobility and preventing falls.

The PCS programme distinguishes itself from other well-known interventions, such as Otago, Vivifrail, and LiFE/aLiFE, by incorporating motivational, self-awareness, and mindfulness components alongside traditional physical exercises. While these other programmes have been shown to be effective in improving balance and reducing fall rates34,35, the PCS programme’s unique integration of cognitive elements from Qi Gong and Tai Chi may offer additional benefits, such as enhanced mental focus and body awareness, which can further support independent living.

The PCS intervention combines conventional functional strength exercises with traditional Tai Chi and Qi Gong practices. The Tai Chi portion of the programme incorporates a sequence that emphasises Yin-Yang polarities, embodying the balance between stillness and activity. These traditional principles are thought to enhance both cognitive and physical functioning by promoting a harmonious integration of body and mind. Recent studies bolster this approach: Henning et al. (2017) discuss the integration of mindfulness within Tai Chi practice, emphasizing its potential to improve cognitive engagement and motor coordination36, while Qu et al. (2024) provide empirical evidence that mindful Tai Chi training leads to notable improvements in mental and physical health outcomes37. Collectively, these insights support the theoretical foundation of the PCS programme and its potential to enhance functional performance in older adults.

Empirical evidence supports links between these TCM concepts and functional outcomes. For example, Tsang and Hui-Chan (2003) found that long-term Tai Chi practitioners had significantly better knee-joint proprioceptive acuity (smaller repositioning error) and wider postural stability limits (greater lean range and faster weight-shift responses) than matched controls38. Likewise, Huston and McFarlane (2016) summarize in their clinical review that Tai Chi training consistently improves static and dynamic balance, contributing to a reduced fall risk in older adults9. Neurophysiological studies also reflect cognitive benefits: Chan et al. (2011) observed that one-month Tan Tien breathing training increased EEG markers of relaxation (alpha asymmetry) and attention (theta coherence), implying enhanced cognitive state6. In line with this, Yang et al. (2020) report that Tai Chi interventions produce moderate improvements in global cognition, memory, attention, and visuospatial processing in older adults with mild cognitive impairment39. Together, these findings indicate that the PCS program’s Tai Chi and Qi Gong elements correspond to measurable gains in balance, proprioception, and cognitive performance.

Although our study did not target improvements in aerobic capacity, we used the established relationship from Cress et al. (2003) as a benchmark to define what constitutes a clinically meaningful change in functional performance. Specifically, the quantified link—where an 8 mL·kg−1·min−1 decrease in VO2peak corresponds to an approximate 3-unit decline in the CS-PFP score—provides an external standard to contextualise the magnitude of changes observed in our study18. This approach allows us to interpret functional performance shifts in terms of a validated physiological measure, thereby enhancing the clinical relevance of our findings.

In summary, the PCS programme builds on established evidence for multi-component exercise programmes by adding elements that address both physical and cognitive aspects of ageing. This holistic approach may provide a more comprehensive strategy for maintaining mobility, reducing fall risk, and promoting overall well-being in older adults.

Strengths and limitations

A key strength of this study is its rigorous design, including the use of the CS-PFP-10, a validated and reliable tool that simulates daily activities and provides objective measures of physical function17. This test offers a more comprehensive assessment of functional performance compared to self-reported measures, which can be subject to bias.

However, several limitations must be acknowledged. The intervention period of 12 weeks, while sufficient for some improvements, may not have been long enough to capture the full potential benefits of the PCS programme, especially for more complex domains such as balance and coordination. The lack of blinding in assessments is another limitation, although efforts were made to minimise bias by separating the intervention and assessment teams. The COVID-19 pandemic also posed challenges, leading to interruptions in recruitment and possible changes in participants’ baseline physical activity levels due to shifting restrictions. Pre-testing and instruction began in the last weeks of the Swiss COVID-19 lockdown, with limitations on personal contact and social interactions. These COVID-19 restrictions were relaxed a few weeks later, potentially altering participants’ (physical) activity in both groups.

Furthermore, the intervention did not specifically target upper body strength, which might explain the lack of improvement in this domain of the CS-PFP-10 test. Future iterations of the PCS programme could consider integrating more upper body exercises to provide a more balanced approach to physical conditioning.

We did not test for changes in cognition. Future research may benefit from incorporating specific cognitive measures to evaluate these aspects more comprehensively.

Generalisability of the findings

Our sample comprised community-dwelling older adults from the Basel region, and we did not collect detailed ethnicity data. This relatively homogeneous sample may limit the generalisability of our findings to more ethnically diverse populations.

The external validity of our study warrants careful consideration. While the promising trends observed in physical functional performance suggest that the PCS intervention may have practical benefits for older community-dwelling adults, several factors may limit the generalisability of these results. First, the study was conducted at a single centre in Basel, Switzerland, and the specific characteristics of our sample may not be representative of older adults in other geographical regions or care settings. Second, assessments were performed under controlled laboratory conditions, which may not fully capture the complexities and variabilities of real-world environments.

Clinical implications and future research

Despite the limitations, the trends observed in this study suggest that the PCS intervention could play a valuable role in maintaining or improving physical function in older adults, particularly in enhancing lower body strength and balance, which are crucial for preventing falls and maintaining independence. Given the growing ageing population and the associated increase in healthcare costs due to physical decline, interventions like PCS could be integrated into community and clinical settings to promote healthy ageing.

Future research should focus on larger, multi-centre trials with longer follow-up periods to confirm the efficacy of the PCS programme and explore its long-term benefits. It would also be beneficial to investigate the mechanisms underlying the improvements observed, particularly the role of cognitive dual-tasking elements in enhancing physical function. Additionally, incorporating assessments of motivation, self-efficacy, and participants’ attitudes towards ageing could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the programme’s impact.

Conclusion

The PCS intervention shows promise in improving different physical functional capacities in older adults, particularly in the domains of lower body strength and balance. While the observed improvements did not reach statistical significance, the positive trends indicate that this programme could be a useful tool in the effort to maintain mobility and independence in the ageing population. Notably, upper body strength experienced a non-significant decline. Further research with larger sample sizes and extended follow-up periods is necessary to fully establish the effectiveness of the PCS programme and its potential to be implemented in broader clinical practice.

Data availability

The dataset analysed during the current study is included as supplementary material (Supplementary Material 2).

References

Chou, C. H., Hwang, C. L. & Wu, Y. T. Effect of exercise on physical function, daily living activities, and quality of life in the frail older adults: A meta-analysis. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 93(2), 237–244 (2012).

Gill, T. M. Assessment of function and disability in longitudinal studies. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 58(Suppl 2), S308–S312 (2010).

Lee, I. M. et al. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: An analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet 380(9838), 219–229 (2012).

World Health Organisation clinical consortium on healthy ageing. Report of consortium meeting held virtually, 18–19 November 2020 (2021).

American College of Sports Medicine, Chodzko-Zajko, W.J., Proctor, D.N., Fiatarone Singh, M.A., Minson, C.T., Nigg, C.R., et al. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Exercise and physical activity for older adults. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 41(7),1510–1530 (2009).

Chan, A. S., Cheung, M. C., Sze, S. L., Leung, W. W. & Shi, D. Shaolin dan tian breathing fosters relaxed and attentive mind: A randomized controlled neuro-electrophysiological study. Evid. Based Complement Alternat. Med. 2011, 180704 (2011).

Liu, H. H., Nichols, C. & Zhang, H. Understanding Yin-Yang philosophic concept behind Tai Chi practice. Holist. Nurs. Pract. 37(5), E75–E82 (2023).

Klein, P., Picard, G., Baumgarden, J. & Schneider, R. Meditative movement, energetic, and physical analyses of three qigong exercises: Unification of eastern and western mechanistic exercise theory. Medicines (Basel) 4(4), 69 (2017).

Huston, P. & McFarlane, B. Health benefits of tai chi: What is the evidence?. Can. Fam. Phys. 62(11), 881–890 (2016).

Podsiadlo, D. & Richardson, S. The timed “Up & Go”: A test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 39(2), 142–148 (1991).

Guralnik, J. M. et al. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: Association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J. Gerontol. 49(2), M85-94 (1994).

Cesari, M. et al. Prognostic value of usual gait speed in well-functioning older people–results from the health, aging and body composition study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 53(10), 1675–1680 (2005).

Cruz-Jentoft, A. J. et al. Sarcopenia: Revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing 48(1), 16–31 (2019).

Cress, M. E. et al. Continuous-scale physical functional performance in healthy older adults: A validation study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 77(12), 1243–1250 (1996).

Cress, M. E., Petrella, J. K., Moore, T. L. & Schenkman, M. L. Continuous-scale physical functional performance test: Validity, reliability, and sensitivity of data for the short version. Phys. Ther. 85(4), 323–335 (2005).

Hardi, I., Bridenbaugh, S. A., Cress, M. E. & Kressig, R. W. Validity of the German version of the continuous-scale physical functional performance 10 test. J. Aging Res. 2017, 9575214 (2017).

Freiberger, E. et al. Performance-based physical function in older community-dwelling persons: A systematic review of instruments. Age Ageing 41(6), 712–721 (2012).

Cress, M. E. & Meyer, M. Maximal voluntary and functional performance levels needed for independence in adults aged 65 to 97 years. Phys. Ther. 83(1), 37–48 (2003).

Brochu, M. et al. Effects of resistance training on physical function in older disabled women with coronary heart disease. J. Appl. Physiol. 92(2), 672–678 (2002).

Cress, M. E. et al. Exercise: Effects on physical functional performance in independent older adults. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 54(5), M242–M248 (1999).

Pinheiro, J., Bates, D., DebRoy, S., et al. R Package ‘nlme.’ Linear Nonlinear Mix Eff Models Version 31–162 (2023).

Sherrington, C. et al. Exercise to prevent falls in older adults: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 51(24), 1750–1758 (2017).

Hackney, M. E. & Wolf, S. L. Impact of Tai Chi Chu’an practice on balance and mobility in older adults: An integrative review of 20 years of research. J. Geriatr. Phys. Ther. 37(3), 127–135 (2014).

Panel on Prevention of Falls in Older Persons AGS, British Geriatrics Society. Summary of the Updated American Geriatrics Society/British Geriatrics Society clinical practice guideline for prevention of falls in older persons. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 59,148–57 (2011).

Sattin, R. W., Easley, K. A., Wolf, S. L., Chen, Y. & Kutner, M. H. Reduction in fear of falling through intense tai chi exercise training in older, transitionally frail adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 53(7), 1168–1178 (2005).

Wayne, P. M. et al. Complexity-based measures inform effects of Tai Chi training on standing postural control: Cross-sectional and randomized trial studies. PLoS ONE 9(12), e114731 (2014).

Sivaramakrishnan, D. et al. The effects of yoga compared to active and inactive controls on physical function and health related quality of life in older adults-systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 16, 1–22 (2019).

Grgic, J. et al. Effects of resistance training on muscle size and strength in very elderly adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sports Med. 50(11), 1983–1999 (2020).

Tarazona-Santabalbina, F. J. et al. A multicomponent exercise intervention that reverses frailty and improves cognition, emotion, and social networking in the community-dwelling frail elderly: A randomized clinical trial. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 17(5), 426–433 (2016).

Lord, S. R. et al. The effect of group exercise on physical functioning and falls in frail older people living in retirement villages: A randomized, controlled trial. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 51(12), 1685–1692 (2003).

Barnett, A., Smith, B., Lord, S. R., Williams, M. & Baumand, A. Community-based group exercise improves balance and reduces falls in at-risk older people: A randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing 32(4), 407–414 (2003).

Phillips, E. M., Schneider, J. C. & Mercer, G. R. Motivating elders to initiate and maintain exercise. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 85(7 Suppl 3), S52–S57 (2004).

Li, F. et al. Tai Chi and fall reductions in older adults: A randomized controlled trial. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 60(2), 187–194 (2005).

Robertson, M. C., Campbell, A. J., Gardner, M. M. & Devlin, N. Preventing injuries in older people by preventing falls: A meta-analysis of individual-level data. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 50(5), 905–911 (2002).

Thomas, S., Mackintosh, S. & Halbert, J. Does the ‘Otago exercise programme’ reduce mortality and falls in older adults?: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing 39(6), 681–687 (2010).

Henning, M., Krägeloh, C. & Webster, C. Mindfulness and taijiquan. Ann. Cognit. Sci. 1, 1–6 (2017).

Qu, P. et al. The effects of mindfulness enhanced Tai Chi Chuan training on mental and physical health among beginners: A randomized controlled trial. Front. Psychol. 15, 1381009 (2024).

Tsang, W. W. & Hui-Chan, C. W. Effects of tai chi on joint proprioception and stability limits in elderly subjects. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 35(12), 1962–1971 (2003).

Yang, J. et al. Tai Chi is effective in delaying cognitive decline in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: Evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Evid. Based Complement Alternat. Med. 2020, 3620534 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank all participants for taking part in our study and Ursula de Almeida Goldfarb, Sylvia Zukerman, and Marcina de Almeida for contributing to the content, design, and conduct of the intervention. We thank Dr. Stephanie A. Bridenbaugh for contributing to the study design and data collection and Prof. Dr. Manfred Berres for conducting the sample size estimation and randomisation.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the Christian Toggenburger Foundation, Switzerland and the Legacy of Wisdom Swiss Association, Switzerland.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RWK was responsible for the study conception and design. JG was responsible for the content, design, and conduct of the intervention. IH, AH, and MB performed material preparation, data collection. RR conducted the statistical analysis. All authors except JG contributed to interpreting the results. MB and RR wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and all authors contributed to subsequent revisions. All authors read, commented on, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Author Jay Goldfarb is the Founder and Director of Legacy of Wisdom, one of the organisations that provided funding for this study. Jay Goldfarb was involved only in the design of the intervention and in the organisation of the training sessions. He had no involvement in data cleaning, data management, analysis, or interpretation of the results. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The trial was conducted according to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local Ethics Committee (Ethikkommission Nordwest- und Zentralschweiz EKNZ, BASEC ID 2018-00067) and has been registered on https://clinicaltrials.gov (NCT04861831). All participants provided written informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study prior to its commencement.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rössler, R., Birrer, M., Haslbauer, A. et al. Efficacy of the power centering for seniors intervention on physical functional performance in older community-dwelling adults: a secondary analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Sci Rep 15, 28908 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13404-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13404-6