Abstract

This paper examines sleep patterns in Romania, a country where long working hours and significant household responsibilities may impact rest. The study highlights key factors influencing perceived sleep quality, with the aim to offer insights for clinicians. Based on a cross-sectional survey 835 with Romanian respondents by the Francophone Space of Pneumology from 2019 to 2020, the study predates the COVID-19 pandemic and therefore avoids potential post-pandemic sleep disruptions. Participants reported their sleep habits, medical conditions, psychological well-being, and work conditions. The study assesses how these factors relate to sleep quality, sleep duration, insomnia, and sleep disturbances. Multivariate analysis reveals that individual perceptions of sleep quality can be misleading when analyzed in isolation. Through hierarchical models, we identify specific predictors of sleep quality. Multivariate analysis showed that good bedroom conditions (OR = 1.63) and physical activity (OR = 1.45) were associated with better sleep perception. Night shifts, female gender, and co-sleeping with pets (OR = 3.68) increased risk of sleep problems. Medical predictors (e.g., STOP-Bang) were not significantly associated. The results are also presented in a practical dashboard, helping healthcare professionals assess sleep disorders more effectively while identifying potential biases in self-reported sleep quality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sleep is a fundamental biological function essential for cognitive, emotional, and physiological health1. It plays a critical role in memory consolidation, metabolic regulation, immune function, and overall well-being. The circadian rhythm, regulated by the hypothalamic suprachiasmatic nucleus, synchronizes sleep with the light-dark cycle and is of fundamental importance for ensuring survival. Disruptions in this cycle can lead to sleep disorders, metabolic imbalances, and mental health issues.

Technological advancements, particularly artificial lighting and electronic devices, have altered natural sleep patterns, contributing to widespread sleep deprivation2,3,4. Contemporary society increasingly prioritizes work, social obligations, and digital entertainment, often at the expense of sufficient sleep. Recent evidence suggests that reduced sleep duration and compromised sleep quality are associated with long work hours, sedentary lifestyles, digital device usage, and environmental factors4,5. For parts of the population, the reduction of outdoors physical activities comes along with bad eating habits and long hours of exposure to blue device lights6. The increasing number of smartphone users is part of the story7, and technology addiction is considered now as a specific condition by the World Health Organization6, while unwanted psychological and well-being effects are reported for digital addicts8,9,10. Such phenomena are claimed to be detrimental to quality of sleep. It is therefore important to look at sleep patterns in societies that have already undertaken technological changes but continue to be under the stress of long work hours and weeks, as well as using a lot of time for house chores.

Romania presents a pertinent case for examining sleep patterns due to its extended workweeks, high domestic labor demands, and evolving technological landscape11,12. This study seeks to explore the self-perception of sleep quality in Romanian adults and to identify the key factors influencing sleep behaviors and outcomes. Our endeavor is in line with other studies13,14, and is important for understanding how people form their representations about sleep.

Materials and methods

We employ SOMNEF (Somnolence dans L’Espace Francophone), a cross-sectional survey carried out by the Francophone Space of Pneumology in 2017–2020 in several countries, including Romania. The Romanian language questionnaire is produced based on the French version of the survey, resulting from a process of translation-back translation15,16,17 and with the support of a group of experts that commented on all intermediary versions of the form, as well as on its final version.

The surveys were collected as paper-assisted-personal-interviews (PAPI). Questionnaires were sent to patients via their pneumologists. We select only Romanian patients, a sample of 835 respondents, that answered the survey between February 2019 and January 2020. Collecting data before pandemics helps to avoid post-pandemic sleep disturbances17 and observe sleeping patterns in regular conditions. The participants were informed in writing about the purpose of the international study, which is to help gain a better understanding of sleep habits and sleep-related issues. They were also informed that the doctor who proposed participation in this questionnaire-based study is a member of the Francophone Scientific Society of Pneumonology and that there are no personal benefits associated with participating in this study. All participants signed consent forms to complete the questionnaires. Self-declared data on age, gender, lifestyle, sleep, and medical history—such as cardiovascular problems, diabetes, or pulmonary disorders, tobacco use, and various behaviors—were collected in accordance with the principles of data protection legislation. All protocols were approved by the ethics committee of the French Society of Pneumology and the Romanian Society of Pneumology.

The sample is not a probabilistic one but depends on response rates for each of the nine centers where data was collected. Gender, age, and the regional distribution were employed into the SPSSINC RAKE procedure to recalibrate the resulting sample in accordance with the structure of the adult population of Romania (Table 1). The weighting procedures cannot solve the educational bias, since the sample is heavily distorted towards university graduates (88% cases as contrasted to less than 20% university graduates in the Romanian adult population).

Several scales were assessed in the study: ODSI is the Observation and Interview-Based Diurnal Sleepiness Inventory and evaluates sleepiness in older adults. It assesses daytime sleepiness in passive and active situations18. Pichot’s Subjective Scale is used to assess fatigue. It consists of eight questions and provides a score ranging from 0 to 3219. Pichot’s Morale Scale is used to evaluate depression20. Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale (HAD) measures anxiety21. STOPBANG screens for obstructive sleep apnea22.

To analyze this data, we start by describing the variation in the variables that we have considered, then we show the associations between various factors and sleep outcomes in bivariate relations. More details are shown in the descriptive tables from the online appendix.

Four sleep outcomes were used as dependent variables. They include (1) self-assessment whether one has enough sleep (dichotomic answers were possible: yes/no), (2) how many hours of sleep are considered as being lost per week as compared to an ideal length of typical sleep, (3) whether sleep quality is labeled as bad, average, or good, and (4) whether the respondents report no insomnia, some incidents, or frequent insomnia.

Independent variables include socio-demographics (gender, age, education), lifestyle elements (sports activities, driving, smoking), work-related (self-defined work/life balance, work time, commuting time), time spent with displays/TVs, sleeping habits (alone/with others, bedroom quality), medication of various sorts, depression and anxiety/related scores.

Finally, we set up multilevel models (respondents nested into localities – that is where is located the medical cabinet where they were patients and where recruited) for each of the four mentioned outcomes. Insomnia and sleep quality were treated as ordinal outcomes, a logit link is employed for having enough sleep, while the loss of sleep hours is considered continuous, being logarithmed to provide a distribution closer to normality. No random effects were allowed. Stata 17 was employed for estimations. All regression assumptions were checked, and all diagnostics indicated no violation.

Results

The study participants reported an average sleep duration of 7.1 h (SD = 1.1 h) on regular days and 8.1 h (SD = 1.5 h) during vacations and weekends. On average, they perceived a sleep deficit of 0.8 h per day. Women reported missing significantly more sleep hours than men; however, gender did not significantly influence other sleep outcomes. Younger generations tended to sleep more on weekends but also reported experiencing greater pressure from inadequate sleep. Higher educational attainment was associated with shorter sleep duration and a stronger perception of sleep deprivation.

Regarding lifestyle habits, 39% of participants engaged in regular physical activity, 66% drove regularly, 22% consumed alcohol in the evening, and 26% were smokers. The average daily commuting time was 1.3 h. In terms of sleep environment and habits, 743 participants (89%) considered their bedroom conducive to good sleep quality. When assessing their sleep, 433 respondents (52%) rated it as good, 350 (42%) as average, and 52 (10%) as poor. Work-related obligations were not perceived as a major sleep disruptor for 54% of respondents.

Sleep arrangements varied, with 34% sleeping alone, 53% sharing a bed with their spouse, 12% sleeping with children, and 9% sleeping with pets. The use of digital devices before bedtime was prevalent, with women and younger individuals being more frequent users. The sample population spent an average of 1.9 h per day watching television, 4.6 h in front of screens for professional purposes, and 2.0 h for personal use.

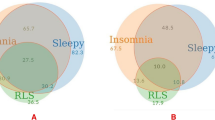

Sleep disturbances were reported frequently, with 231 participants (28%) experiencing at least some insomnia episodes. Among them, 126 (15%) reported frequent insomnia, with 4 (0.5% of the total sample) describing it as severe, 57 (7%) as moderate, and 65 (8%) as mild. Women reported poorer bedroom quality, lower sleep quality, more frequent insomnia, and greater interference of sleep with work schedules. They were also more likely to co-sleep with children.

Nocturnal awakenings were common, with 40% waking up once per night to urinate, 13% waking up more than once, and the rest not waking up to urinate at all. 8% of participants reported waking up due to pain, and 9% reported experiencing leg pain that either prevented them from falling asleep or caused nocturnal awakenings. A small number of respondents—4 individuals—reported waking up to smoke at night, while 6% relied on medication to fall asleep. The mean STOP-Bang score was 0.60 (SD = 0.82), indicating a low overall risk of moderate to severe obstructive sleep apnea.

Analysis of bivariate correlations highlighted several significant associations (Table 2). Women were more likely to report inadequate sleep, greater sleep loss, lower sleep quality, and higher insomnia rates. Older participants were more likely to report having enough sleep but also felt they were losing more sleep hours. Regular physical activity was associated with improvements across all four sleep outcomes, while driving increased the likelihood of experiencing insomnia. Evening alcohol consumption correlated with a lower perception of sleep deprivation. Work-related factors, including night shifts and poor work-life balance, negatively affected sleep quality and duration.

The point estimates indicate b coefficients of determination. Sleep loss was logarithmed for normality reasons. All models are multilevel, with respondents nested in their localities. A logit estimate is used for the first model, while the last two outcomes are ordinal. 95% CIs are displayed.

The point estimates indicate b coefficients of determination. Sleep loss was logarithmed for normality reasons. All models are multilevel, with respondents nested in their localities. A logit estimate is used for the first model, while the last two outcomes are ordinal. 95% CIs are displayed.

Furthermore, we first run models with no controls for actual hours of sleep, and then we repeat them by including such controls (Appendix 1 and Appendix 2).

In models controlling for total sleep hours, gender remained a significant predictor of sleep perception, with women reporting insufficient sleep and more frequent insomnia episodes (Fig. 1). Education levels influenced sleep perceptions, with higher education correlating with shorter perceived sleep duration. Regular exercise increased the likelihood of reporting good sleep, while work-related stress remained a significant deterrent to sleep quality. Co-sleeping with pets was consistently associated with worse sleep outcomes (Fig. 2). Screen use for professional purposes remained negatively associated with sleep quality, but its impact on perceived sleep deprivation was negligible. Medication for memory improvement and the one for heart and blood vessels are associated with better sleep outcomes (Fig. 3).

In summary, the study identified multiple factors influencing sleep perception, including gender, work-life balance, co-sleeping habits, medication use, psychological well-being, and lifestyle behaviors. These findings highlight the complexity of sleep-related perceptions and suggest that practitioners should consider both objective and subjective factors when assessing patients’ sleep health.

The point estimates indicate b coefficients of determination. Sleep loss was logarithmed for normality reasons. All models are multilevel, with respondents nested in their localities. A logit estimate is used for the first model, while the last two outcomes are ordinal. 95% CIs are displayed.

Discussion

Sleep issues, including poor sleep, insomnia and daytime sleepiness, are increasingly recognized as major public health concerns due to their rising prevalence and potentially harmful effects. These effects can lead to physical and mental health problems, reduced productivity, a higher likelihood of accidents, greater healthcare use, and an increased risk of psychiatric conditions.

Our findings emphasize that sleep quality perception is influenced by multiple lifestyles, environmental, and medical factors. The multivariate analysis demonstrated that self-reported sleep quality does not always align with objective sleep-related predictors, underscoring the importance of clinical assessments in evaluating sleep disorders.

Nevertheless, how one feels about owns sleep is essential13,14 and the representations of sleep quality remain important and produce consequences in daily life. Furthermore, the results are stable in controlling the actual length of sleep, showing that they are robust and reliable.

Women exhibited a higher prevalence of sleep disturbances, aligning with previous studies that link gender differences to hormonal fluctuations and caregiving responsibilities According to our results, co-sleepers prove to be a factor for increasing odds to report insomnia, however they do not change the self-perceptions related to quality of sleep, sleeping enough, or sleep loss amongst the ones that do not sleep enough. This creates some discrepancies between our findings and other studies23.The results of a research that assessed the perceived sleep quality in fathers identified as co-sleepers24, highlighted that a “strong” intention to co-sleep was associated with better sleep quality perception and prioritizing co-sleeping fathers were more likely to view co-sleeping as a way to improve perceived sleep quality for the entire family. Since our paper reveals the general factors related to sleeping outcomes, our analysis does not control specificities such as the age of children and the parent’s gender, as they were out of our scope, and the limited space of a journal article is a constraint in this respect. However, further research should consider the interactions between the co-sleeping behavior and the gender of the co-sleeping parent, the age of children, the co-sleeping with both parents, with more children, etc. While the differences may also derive from cultural distinctions, one may also consider the need for comparative research.

A growing body of evidence suggest that co-sleeping with pets may disrupt human sleep25. Our results showed that co-sleeping with pets was significantly associated with insomnia, consistent with research suggesting that pet movement and noise disrupt sleep.

Contrary to common beliefs, the impact of screen time on sleep quality was nuanced. While excessive screen exposure was associated with poorer sleep outcomes, the effect was less pronounced when controlling additional variables. This aligns with emerging literature suggesting bidirectional influences between sleep quality and technology use26,27,28.

Medical conditions and medication use also played a substantial role29. High STOP-Bang scores were predictive of poorer sleep perceptions, reinforcing the need for clinical screening in populations at risk for sleep apnea. Sleep and pain medications paradoxically correlated with worse sleep outcomes, possibly due to dependency effects or underlying conditions necessitating their use.

A post-COVID study on sleeping patterns using another Romanian convenience sample30, although not focused on the same indicators as our work, indicate in bivariate analysis that the differences between men and women, by gender, depending on medication etc. were significant with respect to sleep outcomes. The comparison with the abovementioned study, is an indication that our findings may be valid even after the post-COVID sleep status of Romanian population.

Summing up, our work provides a dashboard of potential sleep covariates to help clinicians assess patients’ sleep concerns more effectively. Understanding the complexities of sleep perception versus objective measures is crucial in designing targeted interventions.

Limitations and future research

This study is limited by its reliance on self-reported data, which may introduce response bias. The cross-sectional design precludes causal inferences, highlighting the need for longitudinal research. The analysis that we proposed was focused on a Romanian sample. Further research should overcome this limitation, due to the limited space of a paper, and extend the analysis to other countries, in order to observe to which extent, the findings are universally valid.

We have partly corrected the bias of a better educated and more urban sample, selected based on visits to the doctor. However, one may still need to consider the population that does not see a doctor. For these non-patients, we cannot estimate to which extent the results could be different. However, from a clinical perspective, this is not affecting our implications, since the findings are robust with respect to the population that seek medical advice from the doctor.

Future studies should also explore the role of cultural influences on sleep behaviors and examine the interplay between use of technology and sleep outcomes in greater depth.

Conclusion

Self-perceived sleep quality is shaped by an intricate interplay of lifestyle habits, environmental conditions, and medical factors. This study provides valuable insights into the determinants of sleep outcomes in Romanian adults, emphasizing the necessity for nuanced clinical assessments. The patients may delay visiting the doctor due to positive representations on quality of sleep. Some patients may even omit narrating episodes of bad sleep due to inconsistency with their own representations.

Although the study is limited by its sample size and focuses on individuals who sought clinical care for sleep-related issues, the results nonetheless offer a practical tool for healthcare practitioners to better evaluate and address sleep-related issues in patient populations.

Data availability

Raw data are available from the authors upon reasonable request. Bogdan Voicu can be contacted for data access via email at Bogdan@iccv.ro.

References

Grigg-Damberger, M. M. Ontogeny of sleep and its functions in infancy, childhood, and adolescence. In: (eds Nevsimalova, S. & Bruni, O.) Sleep Disorders in Children. Cham: Springer; 3–29. (2017).

Finger, A. M. & Kramer, A. Mammalian circadian systems: organization and modern life challenges. Acta Physiol. (Oxf). 231, e13548 (2021).

Czeisler, C. A. Perspective: casting light on sleep deficiency. Nature 497, S13 (2013).

Andersen, M. L., Pires, G. N. & Tufik, S. The impact of sleep: from ancient rituals to modern challenges. Sleep. Sci. 17, e203–e7 (2024).

Grandner, M. A. Sleep, health, and society. Sleep. Med. Clin. 17, 117–139 (2022).

Dresp-Langley, B. & Hutt, A. Digital addiction and sleep. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health ;19. (2022).

Statista Statista Number of Smartphone Users from 2016 to 2021 (in Billions). Technology and Telecommunications. (2021).

Kuss, D. J., Griffiths, M. D., Karila, L. & Billieux, J. Internet addiction: a systematic review of epidemiological research for the last decade. Curr. Pharm. Des. 20, 4026–4052 (2014).

Rumpf, H. J. et al. Including gaming disorder in the ICD-11: the need to do so from a clinical and public health perspective. J. Behav. Addict. 7, 556–561 (2018).

Greenfield, D. N. Treatment considerations in internet and video game addiction: A qualitative discussion. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatr Clin. N Am. 27, 327–344 (2018).

Fuchs-Schündeln, N. & Schündeln, M. The long-term effects of communism in Eastern Europe. J. Economic Perspect. 34, 172–191 (2020).

Voicu, B., Voicu, M. & Strapcová, K. Gendered housework. A Cross-European analysis. Sociologia ;39. (2007).

Okun, M. L. et al. Psychometric evaluation of the insomnia symptom questionnaire: a Self-report measure to identify chronic insomnia. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 05, 41–51 (2009).

Coelho, J. et al. Better characterizing sleep beliefs for personalized sleep health promotion: the French sleep beliefs scale validation study. Front. Public. Health. 11, 1293045 (2023).

Sagheri, D., Wiater, A., Steffen, P. & Owens, J. A. Applying principles of good practice for translation and cross-cultural adaptation of sleep-screening instruments in children. Behav. Sleep. Med. 8, 151–156 (2010).

Oros, M. & Mihălțan, F. Chestionar Pentru identificarea riscului de Apnee în Somn La copii, varianta prelucrată în limba română-studiu preliminar. Intern. Medicine/Medicină Internă ;12. (2015).

Tedjasukmana, R., Budikayanti, A., Islamiyah, W. R., Witjaksono, A. & Hakim, M. Sleep disturbance in post COVID-19 conditions: prevalence and quality of life. Front. Neurol. 13, 1095606 (2022).

Peter-Derex, L. et al. Apport du score ODSI Chez les patients explorés pour somnolence diurne excessive. Médecine Du Sommeil ;16. (2019).

Pichot’s Fatigue Scale.

Benaicha, N. et al. Moroccan taxi drivers fatigue using Pichot questionnaire: A Cross-Sectional survey. J. Health Sci. ;5. (2017).

Zigmond, A. S. & Snaith, R. P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatry. Scand. 67, 361–370 (1983).

Chung, F. et al. High STOP-Bang score indicates a high probability of obstructive sleep Apnoea. Br. J. Anaesth. 108, 768–775 (2012).

Vogiatzoglou, M. et al. Exploring the relationship between Co-Sleeping, maternal mental health and expression of complaints during infancy, and breastfeeding. Healthc. (Basel) ;12. (2024).

D’Souza, L., Kruse, S. P., Makela, E. & Barry, E. S. Co-sleeping fathers’ perceptions of sleep quality with intentional and unintentional co-sleeping. Australian Psychol. 59, 474–485 (2024).

Chin, B. N., Singh, T. & Carothers, A. S. Co-sleeping with pets, stress, and sleep in a nationally-representative sample of united States adults. Sci. Rep. 14, 5577 (2024).

Bauducco, S. et al. A bidirectional model of sleep and technology use: A theoretical review of how much, for whom, and which mechanisms. Sleep. Med. Rev. 76, 101933 (2024).

Heath, M. et al. Does one hour of bright or short-wavelength filtered tablet screenlight have a meaningful effect on adolescents’ pre-bedtime alertness, sleep, and daytime functioning? Chronobiol Int. 31, 496–505 (2014).

AlShareef, S. M. The impact of bedtime technology use on sleep quality and excessive daytime sleepiness in adults. Sleep. Sci. 15, 318–327 (2022).

Van Gastel, A. Drug-Induced insomnia and excessive sleepiness. Sleep. Med. Clin. 13, 147–159 (2018).

Strilciuc, Ş. et al. Sleep health patterns in romania: insights from a nationwide Cross-Sectional online survey. Brain Sci. 14 (11), 1086. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci14111086 (2024). PMID: 39595848; PMCID: PMC11592081.

Funding

No funding was received for this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.S, F.M. participated in the elaboration of the study and supervision of the manuscript writing; F.S., F.M., M.O. participated in data collection and interpretation of the results B.V performed the data preparation, statistical analysisThe first draft of the manuscript was written by B.V and M.O, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. A.D.M, A.R.O and F.M. reviewed the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee (name of institute/committee) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Oros, M., Soyez, F., Moldovan, AD. et al. Sleep and modern life: a population-based study. Sci Rep 15, 27763 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13405-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13405-5