Abstract

Sleep deficiency is becoming increasingly common among adolescents and may lead to aggressive behaviour. This study investigated the association between sleep deficiency and fighting among 1946 school-aged adolescents (mean age: 12.2 ± 0.47 years) in Ningbo city through a two-year longitudinal study and explored the mediating roles of loneliness, sadness, and nervousness. A total of 552 (28.3%) reported sleep deficiency at baseline. During the follow-up period, 347 (17.8%) adolescents engaged in fighting. Sleep deficiency was significantly associated with an increased likelihood of fighting (OR: 1.91, 95% CI: 1.45–2.52) after adjusting for confounders. Compared with boys, girls with sleep deficiency presented a greater risk of fighting (OR: 2.61, 95% CI: 1.44–4.73 for girls; OR: 1.74, 95% CI: 1.27–2.39 for boys). This association persists among adolescents with unhealthy lifestyles. Loneliness partially mediated this relationship (indirect effect β = 0.013, P < 0.05, effect ratio = 12.26%), whereas sadness and nervousness had no significant mediating effect. Studies have shown that sleep deficiency independently predicts adolescent fighting behaviour, with loneliness playing a key mediating role. Interventions that improve sleep hygiene, reduce loneliness, and address lifestyle likelihood factors may help reduce violent behaviour in adolescents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

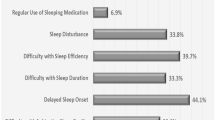

Adolescent sleep deficiency has emerged as a critical public health challenge, marked by increasing global prevalence and multifaceted health consequences1. Epidemiological studies have revealed that approximately 40% of adolescents in Europe and Asia experience sleep-related problems, with 20% meeting the criteria for chronic sleep deficiency2,3. Alarmingly, sleep deprivation (< 8 h/night) affects more than 75% of senior high school students in some regions4,5, with emerging evidence linking such deficits to impaired neurocognitive function6, academic underperformance7, and compromised social adaptation8. Sleep deficiency, encompassing both insufficient sleep duration and poor sleep quality9, defined as the AASM criteria (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index [PSQI] ≥ 5 or sleep duration < 8 h for adolescent)10, is further associated with behavioural dysregulation, including heightened aggression and violence11,12. Notably, physical fighting—a prevalent manifestation of adolescent aggression—has been reported in 23.7% of youth populations13, with longitudinal data suggesting its predictive value for adult violence and suicidality14,15.

The neurobiological mechanisms underlying the association between sleep deficiency and aggression involve prefrontal cortex dysfunction and dysregulated cortisol/serotonin activity, which may exacerbate impulsivity and reduce behavioural inhibition. Sleep deficiency has been shown to impair prefrontal cortex function, which plays a key role in behavioural regulation and executive control. This impairment is associated with increased levels of cortisol and serotonin, both of which have been implicated in the modulation of aggression and violent behaviour, including fighting16,17. Moreover, sleep deficiency reduces inhibitory control, thereby increasing the likelihood of impulsive and aggressive responses18. Evidence from animal models further supports this association. In one study, mice subjected to forced wakefulness via a rotating drum exhibited fatal outcomes within 3 to 14 days. Notably, the cause of death was not solely attributable to sleep deficiency itself but rather to heightened aggression and fighting behaviour among the animals. These findings suggest that sleep deficiency may directly promote aggressive tendencies16.

Sleep deficiency, characterized by insufficient sleep duration and poor sleep quality, adversely affects daytime functioning and is influenced by multiple biological, psychological, and social factors9,19. Previous studies have demonstrated that insufficient sleep duration can contribute to psychological and emotional disturbances, which may in turn mediate the relationship between sleep deficiency and aggressive behaviour. Interventions targeting psychological and emotional well-being have been shown to mitigate the aggression associated with sleep deficiency20. Furthermore, other studies have reported a significant association between poor sleep quality and increased involvement in physical fights among adolescents, with psychological stress identified as a key mediating variable13. Sleep deficiency has also been linked to heightened vulnerability to negative emotional states, including depression, loneliness, anxiety, anger, confusion and fatigue21,22. These findings highlight the importance of identifying specific mediating factors that may help explain the mechanisms underlying the association between sleep deficiency and aggressive behaviours such as fighting.

Cross-sectional studies posit that psychological states such as loneliness, sadness, and nervousness may bridge sleep deficits and aggression13,20,22,23although causal inferences remain constrained by methodological limitations. For example, sleep deprivation has been shown to amplify perceived loneliness, potentially creating a cyclical pattern of social withdrawal and reactive aggression13,23,24. Despite these insights, longitudinal investigations controlling for lifestyle confounders (e.g., screen time, alcohol use) and evaluating the temporal mediating effects of psychological factors (such as loneliness, sadness, and nervousness) remain conspicuously absent from the literature. This two-year prospective cohort study addresses three primary objectives: (1) quantifying longitudinal associations between sleep deficiency and physical fighting in Chinese adolescents; (2) examining gender-specific vulnerability patterns; and (3) evaluating parallel temporal mediation effects of loneliness, sadness, and nervousness. We used social emotional learning theory25 to construct a mediation model of psychological factors (such as loneliness, sadness, and nervousness) and proposed the following hypotheses (see Fig. 1):

H1

Baseline sleep deficiency independently predicts the incidence of fighting behaviour.

H2

Loneliness mediates the relationship between adolescent sleep deficiency and fighting behaviour.

H3

Sadness mediates the relationship between adolescent sleep deficiency and fighting behaviour.

H4

Nervousness mediates the relationship between adolescent sleep deficiency and fighting behaviour.

By employing a rigorous mediation framework and controlling for key lifestyle covariates, this research advances the understanding of modifiable risk pathways for adolescent violence. These findings have direct implications for the development of sleep hygiene interventions and targeted mental health support to mitigate aggression in youth populations.

Methods

Sampling procedure and participants

This school-based prospective cohort study was conducted by the Ningbo Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Ningbo, China. The baseline survey was administered from October–November 2016, and subsequent evaluations were conducted in October 2017 and October 2018. The study adhered to the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the Ethics Review Committee of the Ningbo CDC (No. 201703). To ensure standardization of data collection, strict training was provided to all researchers before the project began to maintain consistency in survey management. Prior to participation, written informed consent from parents or legal guardians was obtained, and all the adolescents participated voluntarily. Before the questionnaire was distributed, detailed explanations about the research objectives were provided to the participants. The collected data will only be used for scientific research purposes and will not be disclosed to the public. The participants were also informed that they had the right to withdraw from the investigation at any time without any consequences. Written informed consent was obtained from parents or legal guardians before participation. All the participants completed the questionnaire within one hour of normal class time.

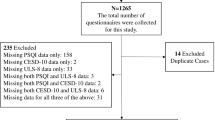

This study used a school-based cluster random sampling method to select seventh-grade students from 13 middle schools across 10 districts of Ningbo City as study participants. This study targeted healthy adolescents, excluding those with major illnesses or value deficiencies. After the investigation was completed, the responses were reviewed, and questionnaires with incomplete or unreasonable answers were deemed invalid and excluded from analysis. Finally, 1946 valid questionnaires were obtained, for a response rate of 89.93%. There were 943 girls and 1003 boys, with an average age of 12.2 ± 0.47 years. The research flow chart is presented in Fig. 2.

Research tools

Data collection utilized a standardized, self-report questionnaire adapted from the U.S. Youth Risk Behaviour Survey (YRBS) developed by the CDC26,27,28. The questionnaire assesses, among other things, sleep duration and quality, physical activity, screen time, smoking, alcohol use, and mental health. It is scored via self-reported multiple-choice or dichotomous classification, with higher scores indicating a greater prevalence of health risk behaviours. In addition, a demographic survey was included in this study. The YRBS questionnaire has good reliability and cultural adaptability and is widely used for adolescent health surveillance29,30. Trained investigators distributed and collected the questionnaires onsite, ensuring completeness.

Measures

Sleep deficiency

Sleep quality was assessed at baseline via the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). A PSQI score ≥ 5 indicated poor sleep quality31,32. Sleep duration was classified into three categories on the basis of the National Sleep Foundation’s recommendations for adolescents (12–13 years): <8 h, 8–9 h, and ≥ 9 h. Sleep deprivation was defined as < 8 h of sleep per night, whereas ≥ 9 h indicated sufficient sleep28. According to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM), insufficient sleep and poor sleep quality are collectively categorized as sleep deficiency33,34.

Fighting behaviour

Fighting behaviour was assessed with the following question: “In the past 12 months, how many times have you been in physical fighting?“. Fighting behaviour was defined as engaging in at least one fight (1 = yes, 0 = no)35. Adolescents who reported at least one fight during the 2017 and 2018 follow-ups were classified as having engaged in fighting.

Mental health factors

Baseline mental health factors included loneliness, sadness, and nervousness36. Loneliness was measured by the following question: “In the past 12 months, how often did you feel lonely?” with responses ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (always). Sadness and nervousness were assessed by asking “In the past 12 months, have you ever felt sad?” (1 = Yes, 0 = No). “In the past 12 months, have you ever felt nervous?” (1 = Yes, 0 = No). These measures are widely validated for assessing adolescent emotional well-being37.

Lifestyle factors and behaviours

Lifestyle behaviours, including physical activity, screen time, smoking, and alcohol use, are assessed at baseline38,39. Physical activity was defined as engaging in moderate to vigorous exercise or muscle-strengthening activities at least once a week (1 = yes, 0 = no). Excessive screen time was defined as more than 2 h per day of TV or computer use (1 = yes, 0 = no). Smoking and drinking were assessed by asking whether the adolescents smoked or consumed alcohol at least once in the past month (1 = yes, 0 = no).

Covariates

Demographic information, including gender, age, parental marital status, and parental education level, was collected at baseline. These covariates are known to influence sleep patterns and behavioural outcomes20.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the characteristics of the adolescents by sleep deficiency and fighting behaviour status. The Kolmogorov‒Smirnov test was used to assess data normality. Normally distributed continuous data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD), whereas nonnormally distributed data are presented as the median and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical data are expressed as frequencies (percentages).

Between-group comparisons were conducted via independent t tests or analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. Logistic regression models were applied to assess the association between sleep deficiency and fighting behaviour, with the results reported as adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) after adjusting for the confounders of age, parental marital status, education level, physical activity, screen time, smoking status and alcohol use.

Subgroup analyses were performed to examine the moderating effects of physical activity, screen time, smoking, and alcohol use on sleep deficiency and fighting behaviour, and forest plots were used to visualize ORs and interactions. The mediating effects explored the indirect effects of loneliness, sadness, and nervousness on the relationship between sleep deficiency and fighting. The “lavaan” package in R was used for parallel mediation effects analysis, and bootstrap resampling was used to estimate the indirect effect. The bias-corrected 95% CI was calculated via bootstrap resampling to ensure the robustness of the inference. If the confidence interval did not contain zero, the mediation effect was considered statistically significant.

All analyses were conducted via R software (version 4.3.1, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). A two-tailed P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Descriptive analysis

Of the 2164 students initially enrolled, 30 were excluded because of missing data, and 188 were lost to follow-up, resulting in a final sample of 1946 adolescents (Table 1; Fig. 2). The mean age of the participants was 12.2 ± 0.47 years. Sleep deficiency was reported by 552 adolescents (28.3%), with similar prevalence rates among boys (28.31%) and girls (28.42%). Significant differences were detected between adolescents with and without sleep deficiency in terms of mild physical activity, muscle-strengthening activity, screen time, smoking, and alcohol use (P < 0.05). Adolescents with sleep deficiency reported higher levels of loneliness, sadness, and nervousness (P < 0.05).

Likelihood of fighting behaviour during follow-up

During the two-year follow-up, 347 adolescents (17.8%) engaged in fighting. Fighting was significantly associated with gender, parental marital status, mild physical activity, internet screen use, smoking, alcohol use, and mental health outcomes (loneliness, sadness, and nervousness) (P < 0.05, Table 2). Boys were more likely to fight (28.41%) than girls were (6.57%). Adolescents from households with divorced, widowed, or separated parents were more likely to fight. Additionally, adolescents who reported fighting were more prone to feelings of loneliness, sadness, and nervousness (P < 0.05).

Longitudinal associations between sleep deficiency and fighting behaviour

Multivariate logistic regression revealed that adolescents with sleep deficiency at baseline were significantly more likely to be fighting during follow-up (OR: 1.95, CI: 1.53–2.48; Table 3). After adjusting for age, parental marital status, education level, physical activity, screen time, cigarette use, and alcohol use, sleep deficiency remained an independent predictor of fighting (OR: 1.91, 95% CI: 1.45–2.52).

Among boys, sleep deficiency increased the likelihood of fighting (OR: 1.84, 95% CI: 1.37–2.46), with the association persisting after adjustment (OR: 1.74, 95% CI: 1.27–2.39). Girls with sleep deficiency presented a greater likelihood of fighting (OR: 3.13, 95% CI: 1.86–5.29), and although the adjusted OR decreased (OR: 2.61, 95% CI: 1.44–4.73), their likelihood remained greater than that of boys (girls OR: 2.61 vs. boys OR: 1.74).

Subgroup analyses

As illustrated in Fig. 3, compared with their peers without sleep deficiency, adolescents with sleep deficiency were almost twice as likely to engage in fighting (OR: 1.95, 95% CI: 1.53–2.48, P < 0.001). Compared with boys, girls with sleep deficiency were more likely to fight (OR: 2.61, 95% CI: 1.44–4.73 for girls; OR: 1.74, 95% CI: 1.27–2.39 for boys). Adolescents with or without moderate physical activity and mild physical activity were more likely to fight (all P < 0.01). Excessive screen time and alcohol use were associated with a greater likelihood of fighting, although the interaction effects were not statistically significant.

Mediation analysis

Mediation analysis explored the roles of loneliness, sadness, and nervousness in the association between sleep deficiency and fighting (Table 4; Fig. 4). Sleep deficiency was positively correlated with fighting (β = 0.076, P < 0.05) and significantly predicted higher levels of loneliness, sadness, and nervousness. Loneliness, in turn, was positively associated with fighting.

Loneliness partially mediated the relationship between sleep deficiency and fighting (indirect effect β = 0.013, P < 0.05; effect ratio = 12.26%). However, sadness and nervousness exhibited no significant mediating effects (P > 0.05), suggesting that the influence of sleep deficiency on fighting is driven primarily by loneliness.

Discussion

Key findings

This 2-year prospective cohort study confirmed that sleep deficiency is an independent likelihood factor for fighting among adolescents (OR: 1.91, 95% CI: 1.45–2.52). Notably, girls with sleep deficiency were more likely to fight than boys were (girls; OR: 2.61 vs. boys; OR: 1.74). Subgroup analysis indicated that the relationship between sleep deficiency and fighting remained significant in adolescents with low physical activity, excessive screen time, and alcohol use (all P < 0.05). While sleep deficiency was associated with loneliness, sadness, and nervousness, only loneliness had a significant mediating effect on fighting.

Sleep deficiency and fighting: a complex relationship

Consistent with previous research, this study highlights the role of sleep deficiency in increasing aggressive and violent behaviour. Adolescents with poor sleep quality are up to 3.61 times more likely to exhibit aggressive tendencies than those with sufficient, high-quality sleep18,20. In our cohort, adolescents with sleep deficiency were twice as likely to fight as their peers were, underscoring the predictive value of sleep deficiency for adolescent aggression. The slightly lower odds observed in this study (OR = 2) than in the literature may stem from the narrower classification of sleep deficiency, which focuses primarily on sleep duration and low sleep quality, whereas other studies included broader categories such as insomnia and sleep deprivation18,20. The relationship between sleep deficiency and fighting may be explained by disruptions in neurocognitive and emotional mechanisms. Sleep deprivation impairs prefrontal cortex function, elevates cortisol and serotonin levels, and fosters antisocial and aggressive behaviours40,41. Poor sleep quality may further exacerbate impulsivity and anger, contributing to aggressive outbursts42,43.

Interestingly, this study revealed that while boys were more likely to fight overall, girls with sleep deficiency were more likely to fight than their boy counterparts were. This finding contradicts previous research suggesting that boys with sleep deficiency are at greater likelihood of violence44,45. This discrepancy may reflect gender-specific emotional responses to sleep deficiency. Research by Short et al. (2015) suggests that adolescent girls are more emotionally vulnerable to sleep loss and exhibit greater susceptibility to depression and anxiety, which may heighten aggression46. Hormonal differences and variations in the stress response may also contribute to this increased likelihood47,48. Further investigations into the sex-specific effects of sleep deficiency on aggression are warranted.

Lifestyle factors and behavioural synergy

The link between sleep deficiency and fighting is modulated by lifestyle factors, with adolescents engaging in unhealthy behaviours being at heightened likelihood. Our findings align with those of previous studies demonstrating that adolescents who lack physical activity, spend excessive time on screens, and consume alcohol are more likely to experience both sleep deficiency and aggression. Physical inactivity is known to impair sleep quality in conjunction with emotional dysregulation and impulsivity, which in turn increase the likelihood of violent behavior49. Moderate physical exercise can promote the mental health of adolescents, alleviate insomnia symptoms, and improve sleep quality50,51. Excessive screen time further exacerbates sleep deficiency by disrupting melatonin secretion and interfering with circadian rhythms52. Adolescents who reported prolonged screen exposure were more likely to experience sleep deficiency and engage in fighting, supporting the need for interventions aimed at reducing screen use. Similarly, adolescents who consumed alcohol presented an increased likelihood of sleep deficiency and fighting, reinforcing the established link between substance use and aggression53,54. Alcohol disrupts the sleep‒wake cycle and impairs impulse control, increasing the likelihood of aggressive behaviours. This highlights the importance of addressing substance use as part of comprehensive interventions targeting adolescent violence and sleep problems.

The mediating role of loneliness

Mental health factors, particularly loneliness, have emerged as significant mediators of the association between sleep deficiency and fighting. Adolescents with higher levels of loneliness were more likely to engage in fighting, and loneliness partially mediated the relationship between sleep deficiency and aggression (indirect effect β = 0.013, P < 0.05; effect ratio = 12.26%). Conversely, sadness and nervousness did not exhibit a significant mediating effect.

These findings are consistent with those of previous studies indicating that sleep deprivation exacerbates loneliness, which in turn increases the likelihood of aggressive behaviour23,42,55,56. Adolescents experiencing sleep deficiency often report elevated levels of psychological distress, which contributes to emotional dysregulation and impulsive behaviour. Addressing loneliness through psychological interventions may therefore reduce the likelihood of fighting in adolescents with sleep deficiency.

Previous studies have also demonstrated that states of loneliness and anxiety can negatively impact sleep quality, creating a bidirectional relationship that fuels aggression13. This underscores the importance of prioritizing adolescent mental health, as interventions targeting loneliness and emotional well-being may concurrently mitigate sleep deficiency and reduce aggressive tendencies.

This study revealed that not all mental health variables serve as significant mediators in the pathway between sleep deficiency and aggressive behaviour. Sadness and nervousness may lead to internalized behaviours such as withdrawal and avoidance rather than externalized fighting behaviours, which may explain why their mediating effect is not significant57,58. Although both sadness and nervousness are correlated with sleep deficiency and fighting, their influence may be moderated by additional factors such as coping mechanisms and levels of social support59,60. In contrast, loneliness appears to exert a more persistent and cumulative effect on aggressive behaviour, potentially making it a more stable and reliable mediator in the relationship between sleep deficiency and fighting.

Strengths and limitations

This study contributes valuable longitudinal evidence on the relationship between sleep deficiency and adolescent fighting, providing insight into the causal pathway and potential mediating factors involved. The prospective design enhances the robustness of the findings, shedding light on long-term associations that cross-sectional studies cannot capture.

However, several limitations should be acknowledged. The reliance on self-reported data introduces the possibility of recall bias and misreporting. Future studies should incorporate objective measures, such as actigraphy or polysomnography, to increase data accuracy61. Additionally, the study population was limited to a specific region, which may restrict the generalizability of the findings. Replication in diverse cultural and geographic contexts is essential to validate these results and explore potential variations.

Conclusion

This study highlights sleep deficiency as an independent likelihood factor for adolescent fighting, with the likelihood being greater among girls and adolescents with unhealthy lifestyles. Loneliness plays a critical mediating role in this relationship, emphasizing the need for comprehensive public health interventions to address sleep, lifestyle, and mental health. Early intervention strategies that promote better sleep hygiene, encourage physical activity, reduce screen time, and address alcohol use may reduce both sleep deficiency and aggressive behaviour. Additionally, psychological interventions aimed at alleviating loneliness and improving emotional well-being could further mitigate the likelihood of fighting but also improve overall mental health and promote healthier development among school-aged adolescents, thereby reducing the health burden and social costs associated with youth violence at a broader societal level.

Data availability

Upon reasonable request, the corresponding author will provide the dataset.

References

Liu, J. et al. Childhood sleep: physical, cognitive, and behavioral consequences and implications. World J. Pediatr. 20, 122–132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12519-022-00647-w (2022).

Parsons, C. E. & Young, K. S. Beneficial effects of sleep extension on daily emotion in short-sleeping young adults: an experience sampling study. Sleep Health. 8, 505–513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2022.05.008 (2022).

Shochat, T., Cohen-Zion, M. & Tzischinsky, O. Functional consequences of inadequate sleep in adolescents: a systematic review. Sleep Med. Rev. 18, 75–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2013.03.005 (2014).

Gradisar, M., Gardner, G. & Dohnt, H. Recent worldwide sleep patterns and problems during adolescence: A review and meta-analysis of age, region, and sleep. Sleep Med. 12, 110–118 (2011).

Defranky, T., Windiani, I. G. A. T., Adnyana, I. G. & A. N., S. Soetjiningsih. The prevalence and risk factors of sleep disorders among adolescent in junior high school. Am. J. Pediatr. 6, 392–396. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajp.20200604.12 (2020).

Owens, J. A. & Weiss, M. R. Insufficient sleep in adolescents: causes and consequences. Minerva Pediatr. 69, 326–336. https://doi.org/10.23736/s0026-4946.17.04914-3 (2017).

Speyer, L. G. The importance of sleep for adolescents’ long-term development. Lancet Child. Adolesc. Health. 6, 669–670. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2352-4642(22)00214-0 (2022).

Woodfield, M., Butler, N. G. & Tsappis, M. Impact of sleep and mental health in adolescence: an overview. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 36, 375–381. https://doi.org/10.1097/mop.0000000000001358 (2024).

Liu, J., Ji, X., Rovit, E., Pitt, S. & Lipman, T. Childhood sleep: assessments, risk factors, and potential mechanisms. World J. Pediatr. 20, 105–121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12519-022-00628-z (2022).

Gohari, A., Baumann, B., Jen, R. & Ayas, N. Sleep deficiency: epidemiology and effects. Sleep Med. Clin. 19, 509–518. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsmc.2024.07.001 (2024).

Simola, P., Liukkonen, K., Pitkäranta, A., Pirinen, T. & Aronen, E. T. Psychosocial and somatic outcomes of sleep problems in children: a 4-year follow‐up study. Child Care Health Dev. 40, 60–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2012.01412.x (2012).

McCaffrey, C., McClure, J., Singh, S. & Melville, C. A. Exploring the relationship between sleep and aggression in adolescents: A cross sectional study using the UK millennium cohort study. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 29, 577–590. https://doi.org/10.1177/13591045231225824 (2024).

Begue, L., Nguyen, D. T., Vezirian, K., Zerhouni, O. & Bricout, V. A. Psychological distress mediates the connection between sleep deprivation and physical fighting in adolescents. Aggress. Behav. 48, 341–347. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.22021 (2022).

Van Dulmen, M. et al. Longitudinal associations between violence and suicidality from adolescence into adulthood. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 43, 523–531. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12036 (2013).

Thompson, M. P., Kingree, J. B. & Lamis, D. Associations of adverse childhood experiences and suicidal behaviors in adulthood in a U.S. Nationally representative sample. Child. Care Health Dev. 45, 121–128. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12617 (2019).

Kamphuis, J., Meerlo, P., Koolhaas, J. M. & Lancel, M. Poor sleep as a potential causal factor in aggression and violence. Sleep Med. 13, 327–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2011.12.006 (2012).

Frøyland, L. R. & von Soest, T. Adolescent boys’ physical fighting and adult life outcomes: examining the interplay with intelligence. Aggress. Behav. 46, 72–83. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21871 (2019).

Van Veen, M. M. et al. Observational and experimental studies on sleep duration and aggression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2022.101661 (2022).

Hasan, M. M., Tariqujjaman, M., Fatima, Y. & Haque, M. R. Geographical variation in the association between physical violence and sleep disturbance among adolescents: A population-based, sex-stratified analysis of data from 89 countries. Sleep Health. 9, 151–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2022.11.007 (2023).

Shi, X., Qiao, X. & Zhu, Y. Emotional dysregulation as a mediator linking sleep disturbance with aggressive behaviors: disentangling between- and within-person associations. Sleep Med. 108, 90–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2023.06.003 (2023).

Whiting, C., Bellaert, N., Deveney, C. & Tseng, W. L. Associations between sleep quality and irritability: testing the mediating role of emotion regulation. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2023.112322 (2023).

Castiglione-Fontanellaz, C. E. G. et al. Sleep regularity in healthy adolescents: associations with sleep duration, sleep quality, and mental health. J. Sleep Res. 32. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.13865 (2023).

Ben Simon, E. & Walker, M. P. Sleep loss causes social withdrawal and loneliness. Nat. Commun. 9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-05377-0 (2018).

Lu, Y. et al. Loneliness, depression and sleep quality among the type 2 diabetic patients during COVID-19 local epidemic: A mediation analysis. Nurs. Open. 10, 6345–6356 (2023).

Carpendale, E. J. et al. Item response theory analysis of self-reported social-emotional learning competencies in an Australian population cohort aged 11 years. School Psychol. (Washington D C) 38, 247–263. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000533 (2023).

Gong, Q. H., Li, S. X., Li, H., Cui, J. & Xu, G. Z. Insufficient sleep duration and overweight/obesity among adolescents in a Chinese population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15050997 (2018).

Eaton, D. et al. Youth risk behavior Surveillance—United states, 2005. J. Sch. Health 76 353–372 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2006.00127.x (2006).

Gong, Q., Li, S., Wang, S., Li, H. & Han, L. Sleep and suicidality in school-aged adolescents: A prospective study with 2-year follow-up. Psychiatry Res. 287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112918 (2020).

Charles, N. E. et al. Test-Retest reliability of Self-Reported substance use and sexual risk behavior among at-Risk adolescents. Psychol. Rep. 127, 432–446. https://doi.org/10.1177/00332941221100459 (2024).

Li, X. et al. Lifestyle behaviors and Suicide-Related behaviors in adolescents: Cross-Sectional study using the 2019 YRBS data. Front. Public Health 9, 766972. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.766972 (2021).

Provini, F. et al. Pittsburgh sleep quality index (PSQI) responses are modulated by total sleep time and wake after sleep onset in healthy older adults. PLoS ONE 17. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0270095 (2022).

Du, Z., Wang, G., Yan, D., Yang, F. & Bing, D. Relationships between the Pittsburgh sleep quality index (PSQI) and vertigo outcome. Neurol. Res. 45, 291–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/01616412.2022.2132728 (2023).

M, K. P. & Latreille, V. Sleep disorders. Am. J. Med. 132, 292–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2018.09.021 (2019).

Sateia, M. J. International classification of sleep disorders-third edition: highlights and modifications. Chest 146, 1387–1394. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.14-0970 (2014).

Semahegn, A. et al. Physical fighting among adolescents in Eastern ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 21, 1732. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11766-w (2021).

Liu, T. et al. Comparison of networks of loneliness, depressive symptoms, and anxiety symptoms in at-risk community-dwelling older adults before and during COVID-19. Sci. Rep. 14. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-65533-z (2024).

Steen, O. D., Ori, A. P. S., Wardenaar, K. J. & van Loo, H. M. Loneliness associates strongly with anxiety and depression during the COVID pandemic, especially in men and younger adults. Sci. Rep. 12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-13049-9 (2022).

Yang, Y. et al. Chronotype is associated with eating behaviors, physical activity and overweight in school-aged children. Nutr. J. 22, 50. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12937-023-00875-4 (2023).

Gong, Q. H. et al. Associations between sleep duration and physical activity and dietary behaviors in Chinese adolescents: results from the youth behavioral risk factor surveys of 2015. Sleep Med. 37, 168–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2017.06.024 (2017).

Cao, L. et al. Bidirectional association between sleep quality or duration and aggressive behaviour in early adolescents: A cross-lagged longitudinal study. J. Affect. Disord. 334, 197–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2023.04.119 (2023).

Paiva, T. & Canas-Simião, H. Sleep and violence perpetration: A review of biological and environmental substrates. J. Sleep Res. 31. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.13547 (2022).

Wang, W. et al. The impact of sleep quality on emotion regulation difficulties in adolescents: a chained mediation model involving daytime dysfunction, social exclusion, and self-control. BMC Public Health 24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-19400-1 (2024).

López-Cepero, A. et al. Association between poor sleep quality and emotional eating in US Latinx adults and the mediating role of negative emotions. Behav. Sleep Med. 21, 162–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/15402002.2022.2060227 (2022).

Fahlgren, M. K., Cheung, J. C., Ciesinski, N. K., McCloskey, M. S. & Coccaro, E. F. Gender differences in the relationship between anger and aggressive behavior. J. Interpers. Violence. 37, NP12661–NP12670. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260521991870 (2021).

Van Veen, M. M., Lancel, M., Beijer, E., Remmelzwaal, S. & Rutters, F. The association of sleep quality and aggression: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Sleep Med. Rev. 59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2021.101500 (2021).

Short, M. A. & Louca, M. Sleep deprivation leads to mood deficits in healthy adolescents. Sleep Med. 16, 987–993. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2015.03.007 (2015).

Acheson, A., Richards, J. B. & de Wit, H. Effects of sleep deprivation on impulsive behaviors in men and women. Physiol. Behav. 91, 579–587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.03.020 (2007).

Zhou, L., Kong, J., Li, X. & Ren, Q. Sex differences in the effects of sleep disorders on cognitive dysfunction. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2023.105067 (2023).

Passos, N. F., Freitas, P. D., Carvalho-Pinto, R. M., Cukier, A. & Carvalho, C. R. F. Increased physical activity reduces sleep disturbances in asthma: A randomized controlled trial. Respirology 28, 20–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/resp.14359 (2022).

Shen, Q. et al. The chain mediating effect of psychological inflexibility and stress between physical exercise and adolescent insomnia. Sci. Rep. 14, 24348. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75919-8 (2024).

Xiao, T., Pan, M., Xiao, X. & Liu, Y. The relationship between physical activity and sleep disorders in adolescents: a chain-mediated model of anxiety and mobile phone dependence. BMC Psychol. 12, 751. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-024-02237-z (2024).

Lissak, G. Adverse physiological and psychological effects of screen time on children and adolescents: literature review and case study. Environ. Res. 164, 149–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2018.01.015 (2018).

Merianos, A. L., Stone, T. M., Mahabee-Gittens, E. M., Jandarov, R. A. & Choi, K. Tobacco smoke exposure and sleep duration among U.S. adolescents. Behav. Sleep Med. 22, 234–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/15402002.2023.2232498 (2023).

Phiri, D. et al. Prevalence of sleep disturbance among adolescents with substance use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Mental Health 17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-023-00644-5 (2023).

Doane, L. D. & Thurston, E. C. Associations among sleep, daily experiences, and loneliness in adolescence: evidence of moderating and bidirectional pathways. J. Adolesc. 37, 145–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.11.009 (2013).

Kabadayi, F. Smartphone addiction, depression, distress, eustress, loneliness, and sleep deprivation in adolescents: a latent profile and network analysis approach. BMC Psychol. 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-024-02117-6 (2024).

Leventhal, A. M. & Sadness Depression, and avoidance behavior. Behav. Modif. 32, 759–779. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445508317167 (2008).

Zeman, J., Shipman, K. & Suveg, C. Anger and sadness regulation: predictions to internalizing and externalizing symptoms in children. J. Clin. Child. Adolesc. Psychol. 31, 393–398. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp3103_11 (2002).

Shu, J., Bolger, N. & Ochsner, K. N. Social emotion regulation strategies are differentially helpful for anxiety and sadness. Emotion 21, 1144–1159. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000921 (2021).

Ken, C. S., Guan, N. C. & Commentary Internalizing problems in childhood and adolescence: the role of the family. Alpha Psychiatry. 24, 93–94. https://doi.org/10.5152/alphapsychiatry.2023.080523 (2023).

Kahn, M. et al. Sleep, screen time and behaviour problems in preschool children: an actigraphy study. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 30, 1793–1802. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-020-01654-w (2020).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to Jian Song for providing careful guidance and suggestions during the paper writing process.

Funding

This study was funded by grants from the Science and Technology Project for Disease Control and Prevention of Zhejiang Province (No. 2025JK070), Guangxi Key Research and Development Program (No. Guike AB23026047), Ningbo Top Medical and Health Research Program (No.2023020713), and Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang (LTGY24H260007).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wei Wei: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Conceptualization. Lu Pan: Formal analysis, Data curation. Si-Jia Wang: Conceptualization, Investigation. Si-Xuan Li: Conceptualization, Investigation. Qing-Hai Gong: Resources, Methdology, Project administration, Funding acquisition.Xin Xiao: Methodology, Visualization, Software, Writing–review & editing, Funding acquisition.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study adhered to the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the Ethics Review Committee of the Ningbo CDC (No. 201703). All research procedures and data collection were performed in a manner compliant with the related legal requirements.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from parents or legal guardians before participation.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wei, W., Pan, L., Li, SX. et al. Loneliness mediates the association between sleep deficiency and fighting in school-aged adolescents: a 2-year longitudinal study. Sci Rep 15, 29938 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13505-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13505-2