Abstract

In recent years, haze has significantly hindered the quality and efficiency of daily tasks, reducing the visual perception range. Various approaches have emerged to address image dehazing, including image enhancement, restoration, and deep learning-based dehazing methods. While these methods have improved dehazing performance to some extent, they often struggle in bright regions of the image, leading to distortions and suboptimal dehazing results. Moreover, dehazing models generally exhibit weak noise resistance, with the PSNR value of dehazed images typically falling below 30 dB. Residual noise remains in the processed images, leading to degraded visual quality. Currently, it is challenging for dehazing models to simultaneously ensure effective dehazing in bright regions while maintaining strong noise suppression capabilities. To address both issues simultaneously, we propose an image dehazing algorithm based on deep transfer learning and local mean adaptation. The framework consists of several key modules: an atmospheric light estimation module based on deep transfer learning, a transmission map estimation module utilizing local mean adaptation, a haze-free image reconstruction module, an image enhancement module, and a noise reduction module. This design ensures stable and accurate atmospheric light estimation, enabling the model to process different regions of hazy images effectively and prevent distortion artifacts. Furthermore, to enrich the details of the dehazed pictures and enhance the dehazing performance while improving the model’s noise resistance, we incorporate an image enhancement module and a noise reduction module into the proposed dehazing framework. To validate the effectiveness of the proposed algorithm, we conducted dehazing experiments on a Self-Made Synthetic Hazy Dataset, the SOTS (outdoor) dataset, the NH-HAZE dataset, and O-HAZE dataset. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed dehazing model achieves superior performance across all four datasets. The dehazed images exhibit no color distortion, and the PSNR values consistently exceed 30 dB, indicating that the dehazed images are of high quality. The dehazed images also demonstrate a significant advantage in SSIM performance compared to mainstream dehazing algorithms, consistently achieving a similarity of over 85%. This indicates that the proposed dehazing model effectively mitigates distortion while enhancing noise resistance, exhibiting strong generalization capabilities across different datasets. The experimental results confirm that the proposed dehazing algorithm handles bright regions, such as the sky, and significantly reduces residual noise in the dehazed images. Both aspects demonstrate strong performance, validating the effectiveness and superiority of the proposed dehazing model. Furthermore, the algorithm achieves consistently good dehazing performance across all three hazy datasets, demonstrating its generalization capability. This study presents a novel dehazing method and theoretical framework that can be effectively applied to scenarios such as autonomous driving and intelligent surveillance systems. The proposed model offers a novel approach to image dehazing, contributing to advancements in related fields and promoting further development in haze removal technologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The presence of haze causes objects in images to become blurred, weakening the representation of image details and reducing object visibility1. Moreover, haze significantly hinders the rapid progress and development of fields such as autonomous driving2making it difficult for autonomous driving systems to interpret road scene information accurately, and severely affecting the efficiency and quality of intelligent transportation systems’ daily operations. Image dehazing helps obtain clearer and more visible images, enabling intelligent systems to more accurately interpret image information3. Therefore, image dehazing has become a widely studied and significant research topic.

Image dehazing methods can be broadly categorized into three types: enhancement-based approaches, restoration-based approaches, and deep learning-based approaches4. Enhancement-based dehazing algorithms improve image detail and overall clarity by adjusting properties such as color, brightness, and contrast5. Representative methods in this category include Histogram Equalization6the Retinex algorithm7LCGE8LBAF9SAEN10and MSEN-PFE11.In addition, Wang et al.12developed the Detail-Enhancement Attention Network (DEA-Net), which effectively integrates structure preservation and attention mechanisms to enhance edge structural information while improving overall image quality. Overall, enhancement-based dehazing methods perform well under light to moderate haze conditions. However, they still face significant challenges in complex, high-density haze scenarios, such as insufficient image information, color distortion, and limited generalization ability.

Restoration-based dehazing methods aim to recover clear, haze-free images by analyzing the atmospheric scattering model and leveraging physical priors. A representative method in this category is the Dark Channel Prior (DCP) algorithm13which has been widely applied across various domains. The DCP algorithm is developed based on the atmospheric scattering model; however, it tends to produce noticeable distortions in bright regions of hazy images, such as the sky. In addition, its limited noise robustness often results in residual artifacts in the dehazed output.

In recent years, deep learning-based dehazing methods have continuously developed and achieved good dehazing results on synthetic hazy datasets. These methods annotate haze information in hazy datasets, allowing the model to learn haze features in images. However, deep learning-based dehazing methods often rely on synthetic hazy images for training, which limits the scope of haze feature learning14,15,16. Additionally, since haze in real-world scenarios has various characteristics, these methods tend to have weak generalization performance across different datasets, and the results on real hazy images are often suboptimal. Furthermore, these methods involve a large number of parameters, making them challenging to deploy and apply17,18,19. Currently, all three types of dehazing methods face challenges in simultaneously maintaining good dehazing performance in bright regions and strong noise resistance. There is still room for performance improvement in this regard.

Hu et al.20to improve dehazing performance in bright regions, built upon the DCP dehazing model. They first calculated the gray level with the fewest discontinuities in the gray histogram and used it as the segmentation threshold to adapt to haze features in maritime images, specifically for segmenting bright regions such as the sky. Based on this, they proposed an enhanced DCP method, which locally optimizes the transmission map in the sky region and globally optimizes it across the entire image. This effectively improves dehazing clarity; however, the results in bright regions still exhibit slight distortion, and the model’s noise resistance remains weak. Wang et al.21 proposed an adaptive image dehazing algorithm based on bright region detection to improve the dehazing performance of the DCP algorithm in bright regions. The algorithm first sets the lower bounds for the transmission map and introduces an adaptive correction factor to adjust the transmission in the bright field regions, which effectively alleviates the limitations of the DCP in wide and high-brightness areas. Experimental results show that the proposed method significantly enhances the dehazing performance in bright regions. However, the issue of weak noise resistance in the model remains unresolved. Tian et al.22 proposed an improved DCP algorithm combined with Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) to address issues such as color distortion in the original DCP algorithm. However, similar problems, such as those in bright regions and weak noise resistance, persist in their approach. Guan et al.23proposed a polarization-assisted DCP dehazing method to address the shortcomings of the original DCP algorithm. However, their approach still fails to achieve both effective dehazing and strong noise resistance simultaneously. Han et al.24 proposed a remote sensing image dehazing method based on the atmospheric scattering model and DCP constraint network. The branch fusion module in this dehazing network is used to optimize feature weights, improving dehazing efficiency. To further improve dehazing performance, the PSD algorithm25 establishes a dehazing network composed of the DCP, Bright Channel Prior26and histogram equalization to guide the recovery of clear images. The Dehamer algorithm27 recovers clear images from hazy ones without relying on atmospheric light and transmission values, but it also reduces dehazing efficiency. Zheng et al.28 constructed a physics-aware dual-branch unit based on the atmospheric scattering model, and combined it with a contrastive regularization method to establish the C2PNet dehazing network. This greatly improved the dehazing performance. However, the model’s noise resistance does not exhibit strong generalization across different datasets. The RIDCP algorithm29 leverages a pre-trained VQGAN to obtain high-quality codebook priors, using these priors for controllable high-quality prior matching, thereby achieving feature restoration for hazy images. The DCMPNet al.gorithm30considering the potential relationship between scene depth information and hazy images, proposes a dual-task collaborative framework to achieve single-image dehazing. Experimental results show that this model effectively enhances the dehazing visualization performance. However, its noise resistance performance lacks generalization across different datasets. In summary, the above dehazing methods exhibit unsatisfactory performance in handling bright regions of images and in terms of noise resistance, with issues such as distortion and weak noise resistance. To address these problems, we propose an image dehazing algorithm based on deep transfer learning and local mean adaptation (DTLMA).

The main contribution of this paper is summarized as follows:

-

1.

We designed an atmospheric light estimation module based on deep transfer learning. Traditional methods rely on statistical priors, and once these assumptions are violated, the accuracy of atmospheric light estimation deteriorates. Additionally, the process of estimating atmospheric light is prone to being influenced by image noise and low contrast, resulting in slower computational speed. To address the above issues, we improved the MobileNetV2 model to learn both global and local image features from large-scale synthetic and real-world data. This enhancement strengthens the model’s adaptability across different scenarios, helping to avoid failure cases and improve the speed of atmospheric light estimation.

-

2.

We designed a transmission estimation module based on local mean adaptation. To enable the dehazing model to effectively handle both bright and non-bright regions in an image, we apply window-based processing to different locations of the image. First, we calculate the average transmission value for different locations in the image to distinguish between bright and non-bright regions in each window. Next, we design a novel transmission estimation method to ensure that the transmission in bright regions within each window better approximates that in non-bright regions. Finally, we apply guided filtering to the transmission map to reduce noise. Overall, this ensures that the model can appropriately adjust the transmission values for different locations in the image.

-

3.

We designed an image enhancement module. The dehazed image retains some level of detail, but there may be a slight color shift compared to the original image in terms of color restoration. To address the above issues, we first apply wavelet denoising to the dehazed image to effectively reduce noise introduced by the dehazing algorithm. Next, we convert the dehazed image from the RGB space to the Lab space, where we perform adaptive histogram equalization on the L channel (luminance channel) separately. Finally, we use a weighted fusion method to moderately enhance the contrast, ensuring that the dehazed image appears more natural and closer to the original image.

-

4.

We designed an image denoising module to address the weak noise resistance of the dehazing model, which primarily results from the lack of noise handling, affecting the quality of the dehazed image. To solve this issue, we added an image denoising module to the existing dehazing model. To preserve the edge details of the image while enhancing its quality, we introduced a guided filtering model to improve dehazing performance. To select the appropriate number of guided filtering layers, we conducted ablation experiments to ensure that the model enhances image quality without damaging image detail.

Related work

New dehazing methods have emerged in recent years. These methods aim to improve the visualization of dehazed images, enhance dehazing performance in bright regions, and reduce model complexity. Zheng et al.31to ensure the navigation safety of intelligent ships in complex hazy weather, proposed a lightweight real-time dehazing method based on an integrated dehazing network for natural environments. This method uses hybrid dilated convolutions to construct the dehazing network, which expands the receptive field and improves feature extraction without increasing the model’s computational load. However, experimental results show that the model has weak noise resistance performance. Huang et al.32 pointed out that real-world hazy images lack labels, and most deep learning-based models are trained on synthetic datasets, neglecting the complexity and unpredictability of real-world haze. They proposed a Retinex-based decomposition cycle dehazing network (DCD-Net). Experimental results show that the dehazed images processed by this method generally have a PSNR performance lower than 30 dB. Cui et al.33 aimed to improve dehazing performance by enhancing spatial-spectral learning, proposing the EENet efficient dehazing network. Chen et al.34 to further enhance dehazing effects and reduce computational complexity, proposed the DPTE-Net lightweight dehazing network. This method considers the quadratic increase in complexity of self-attention modules with image resolution, which hinders their applicability on resource-constrained devices. By replacing the traditional self-attention module with the pooling mechanism of DPTE-Net, the model retains the learning capability of ViT while reducing computational requirements. However, the model’s noise resistance and dehazing efficiency still need improvement. Ma et al.35 proposed a polarization dual-channel multi-scale decomposition algorithm to improve dehazing effects for both distant and near scenes in images. The main strategy is to extract the near and far scenes separately and then combine them into a dehazed image based on fusion principles. Cong et al.36 proposed a semi-supervised real-world data dehazing model to enhance the generalization performance of dehazing models. Experimental results show that the dehazing performance of the above method varies across different datasets. In summary, the dehazing models based on image restoration20,21,22,23 and deep learning27,28,29,30 have effectively improved dehazing performance to some extent, but the models generally exhibit weak noise resistance. In general, improving the model’s noise resistance requires including a denoising module in the dehazing process to filter out image noise. However, the introduction of the denoising module reduces the clarity and other relevant features of the dehazed image, leading to blurriness. Therefore, improving both the dehazing effect in bright regions and the model’s noise resistance has become a major challenge.

Method

To simultaneously address the above two issues, an image dehazing algorithm based on deep transfer learning and local mean adaptation was designed. This algorithm includes the design of several modules: a deep transfer learning-based atmospheric light value solver, a local mean adaptation-based transmission map solver, a haze-free image restoration module, an image enhancement module, and an image denoising module. To mitigate the influence of various interfering factors during atmospheric light estimation, we employ transfer learning to estimate atmospheric light. The pre-trained MobileNetV2 model is improved to achieve more stable and accurate results. In addition, considering that different regions of an image require varying adjustments of transmission values, a local mean adaptive method is adopted to enhance the dehazing performance in different regions. Furthermore, since dehazing may result in the loss of image details, adaptive histogram equalization is applied to the L-channel of the dehazed image to enrich detailed information. Finally, as noise is a key factor affecting the quality of dehazed images, and guided filtering offers an edge-preserving advantage, an edge-preserving filtering model is integrated into the dehazing process to improve noise robustness and enhance image quality.

The structure of the proposed model

To ensure that the model performs well in bright areas while maintaining strong noise resistance, a novel image dehazing algorithm based on deep transfer learning and local mean adaptation is designed. The specific structure of the proposed model is shown in Fig. 1. It first includes the Atmospheric Light Estimation Module Based on Transfer Learning (ALETL), followed by the Transmission Estimation Module Based on Local Mean Adaptation (TELMA). Additionally, it contains the Haze-Free Image Estimation Module (HFIEM), and finally, the Image Enhancement Module (IEM) and Image Denoising Module (IDM).

Image Dehazing Algorithm Based on Deep Transfer Learning and Local Mean Adaptation. The block diagrams with different background colors in Fig. 1 represent the following modules: (a) ALETL module, (b) TELMA module, (c) HFIEM module, (d) IEM module, and (e) IDM module.

The DTLMA model begins with an enhanced MobileNetV2 network designed for atmospheric light estimation, which integrates the physical interpretability of traditional models with the powerful modeling capabilities of deep learning. To better accommodate regression tasks, the original classification layers are removed and replaced with fully connected regression layers. The use of depthwise separable convolutions, linear bottlenecks, and inverted residual structures effectively reduces computational complexity while enhancing feature representation. Moreover, the inclusion of a global feature extraction module improves the model’s adaptability to complex scenes. The proposed approach provides a balanced advantage in accuracy, efficiency, deployability, and theoretical soundness. It is well-suited for a wide range of practical applications compared with traditional hybrid methods and end-to-end deep learning models. In the estimation of image transmission, we propose a novel approach based on locally adaptive mean values to compute transmission maps. Unlike existing deep learning-based dehazing models, our method adaptively adjusts the transmission values across different regions of the image, which theoretically enhances the dehazing performance in spatially heterogeneous areas. After obtaining the initial dehazed image, an image enhancement module is introduced to enrich fine details and mitigate potential information loss caused by the dehazing process. Furthermore, we innovatively integrate guided filtering into the dehazing framework. Compared to other deep learning-based methods, this integration theoretically provides superior noise robustness and better preservation of image structure.

Design of the atmospheric light Estimation module based on deep transfer learning

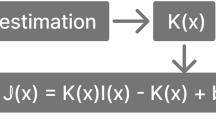

Dehazing methods based on image restoration rely on the atmospheric scattering model37,38,39 to estimate the haze-free image. The expression of the atmospheric scattering model is as follows:

In the equation, I(x) represents the input hazy image, t(x) denotes the transmission map, J(x) is the haze-free image to be recovered, and A is the atmospheric light value.

According to the atmospheric scattering model, the values of atmospheric light and transmission directly impact the dehazing performance40,41,42. Traditional methods for estimating atmospheric light often assume that at least one color channel in non-sky regions is close to zero. However, this assumption may fail in certain scenarios. These include heavy fog, white objects, or strong lighting conditions, which can lead to significant estimation errors. Secondly, the estimation of atmospheric light is typically performed by selecting the brightest 0.1% of pixels in the dark channel image. However, this approach is highly susceptible to bright spots, halos, and strongly reflective objects. This susceptibility leads to inaccurate estimations. Lastly, the traditional method requires computing local minimum values and performing window-based searches, resulting in high computational complexity, which makes it unsuitable for real-time applications. To accurately estimate atmospheric light, we designed an atmospheric light estimation module based on transfer learning, as illustrated in Fig. 2.

The training process for the atmospheric light estimation model is as follows:

1) Dataset preparation: Reside (ITS).

2) The dataset is divided into a training set and a testing set. The training set consists of 12,990 pairs of hazy and clear images, while the testing set includes 1,000 hazy and clear images.

3) We calculated the atmospheric light values for both hazy and clear images in the training and test sets, and generated the corresponding labels. The labels are denoted as trainhazy.m, trainclear.m, testhazy.m, and testclear.m, respectively. The atmospheric light is assumed to be spatially uniform and represented by a fixed RGB vector across the entire image. First, the dark channel of each hazy image was computed by selecting the minimum RGB component at each pixel. Then, pixels corresponding to the top 0.1% darkest values in the dark channel were selected as candidate regions. Among these candidate pixels, the maximum RGB value was chosen as the atmospheric light.

Here, \({I_{{\text{h}}azy}}(y)\) represents the RGB value of the hazy image at a given pixel position, and Ωrefers to the set of candidate region pixels.

4) Load the MobileNetV2 pre-trained model, remove the original classification layer, and add a new regression layer.

5) Set the training optimizer to Adam, with a batch size of 32 and 20 epochs for training.

6) The definition of the loss function is as follows:

The prediction value of atmospheric light by the model is denoted as, and the true atmospheric light value of the hazy image is denoted as\({A_{{\text{hazy}}}}\).

7) Plot the performance loss curves for training and testing.

Deep transfer learning is a method that utilizes existing model knowledge and applies it to new tasks. The core idea is to pre-train a deep neural network on a large-scale dataset to learn general features. The pre-trained model is then transferred to a smaller target task dataset, reducing computational overhead and improving generalization ability. We use MobileNetV2 as the feature extraction network, leveraging depthwise separable convolutions to reduce computational complexity. Additionally, we incorporate linear bottlenecks and inverted residual structures to improve the model’s feature representation capabilities. To enable MobileNetV2 to better predict atmospheric light values, we made structural adjustments to the model. First, we remove the final classification layer and retain the global feature extraction layer. Then, we add a fully connected regression layer to directly predict the atmospheric light. The modified network architecture is shown in Fig. 3.

The modified MobileNetV2 network structure is as follows:

-

1)

Input Image (Hazy Image): This serves as the input to the model, with a size of 224 × 224 × 3.

-

2)

Standard Convolution Layer (Conv 3 × 3): This layer is responsible for extracting the initial features from the image.

-

3)

Depthwise Separable Convolution: This operation reduces computational complexity while extracting more diverse and rich features.

-

4)

Bottleneck Block: Through the 1 × 1 convolution, this block performs channel compression and expansion, enhancing the feature representation capability.

-

5)

Skip Connection: This mechanism facilitates better gradient flow, thus improving training stability.

-

6)

Global Average Pooling (GAP): This operation further compresses the feature map dimensions and outputs a global feature vector.

-

7)

Fully Connected Layer (FC Layer): This layer directly maps the GAP features to the output atmospheric light value.

Finally, the output layer of the model consists of a single regression output node, representing the atmospheric light value. Through transfer learning, the low-level features pretrained by MobileNetV2 are utilized, and the final fully connected layer is retrained to adapt the model for atmospheric light value estimation. The original classification layer of MobileNetV2 is removed, and a new fully connected layer for regression is added, which can be seen as an independent layer appended to the MobileNetV2 architecture. MobileNetV2 primarily serves as the feature extraction component, ultimately outputting a feature vector. The fully connected (FC) layer is an independent additional layer responsible for mapping the extracted features to the atmospheric light value A. During the atmospheric light value training process, the FC layer is appended after MobileNetV2, as expressed in the following equation:

Where I is the input image,\({f_\theta }\) represents the MobileNetV2 transfer learning model, and A is the predicted atmospheric light value.

Design of transmission Estimation module based on local mean adaptation

Considering that the dark channel prior theory does not hold in bright regions, where the corresponding dark channel values approach the atmospheric light value, the expression is as follows:

At this point, the expression for the transmission estimation is as follows:

Equation (5) indicates that the dark channel prior theory is not suitable for bright regions in an image, where the estimated transmission values are significantly lower than the true values. This limitation results in suboptimal performance of DCP-based dehazing algorithms in bright areas such as the sky. To improve transmission estimation and enhance the visual quality of dehazed images, we designed a transmission estimation module based on local mean adaptation. The detailed procedure is as follows.

1) We first divide the image into multiple windows to adjust the transmission values regionally. Within each window, the image is segmented into bright and non-bright regions using a brightness mask. The criteria for setting the mask are as follows:

\({M_{bright}}(x)\)represents the bright region mask, which is set to 1 if the transmission value within the window is lower than the overall mean transmission; otherwise, it is set to 0.\({M_{{\text{dark}}}}(x)\) represents the dark region mask, which is complementary to\({M_{bright}}(x)\).\(\mathop t\limits^{ - } (x)\)represents the local mean transmission value within the window, used to differentiate between bright and non-bright regions.

2) Calculate the local transmission mean for the bright and non-bright regions of each window separately:

\({\mathop t\limits^{ - } _{bright}}(x)\)represents the local transmission mean of the bright region. \({\mathop t\limits^{ - } _{dark}}(x)\)represents the local transmission mean of the dark region.\({\Omega _{{\text{bright}}}}(x)\)and\({\Omega _{dark}}(x)\)represent the pixel sets of the bright and non-bright regions within the local window, respectively.

3) After segmenting each window into bright and non-bright regions and obtaining the average transmission values for both regions, we designed a locally adaptive mean method to uniformly estimate the transmission value within the window. The expression is as follows:

\(t^{'}(x)\)represents the corrected transmission rate, and\(\varepsilon\)represents a constant to prevent division by zero, set to 0.001. As shown in Eq. (10), within a transmission adjustment window, transmission values belonging to the non-bright region remain largely unchanged. In contrast, transmission values within the bright region are increased based on their original values, thereby further refining the transmission estimation. This process effectively adjusts the transmission values for both bright and non-bright regions within the window.

4) To further smooth the transmission rate and improve the quality of the restored image, we apply guided filtering to the transmission rate:

\({I_{{\text{gray}}}}\).represents the guidance image, which is the reference image used in the filtering process, typically chosen as a grayscale image. r represents the filter window radius, and\(\zeta\)represents the regularization parameter, which helps prevent over-enhancement of local contrast and prevents noise from being amplified during the filtering process.

In real-world scenarios, we need to consider two main issues. First, the degree of transmission rate correction may vary at different positions in the image. For example, bright areas such as the sky typically have lower transmission rates and require higher correction, while other regions may need less adjustment. If we only use the mean transmission rate of non-bright regions to adjust local areas in the image, it may lead to over-correction or under-correction in certain areas. In addition, for foggy images, the threshold for dividing bright and non-bright regions may vary across different positions in the image. To address this issue, we first calculate the average transmission rate for each local window. We then use this average value as the threshold to classify the bright and non-bright regions within each window. Then, we adjust the transmission rates of the bright and non-bright regions within each local window, ensuring that the transmission rates of both regions are optimized towards the average transmission rate of the non-bright region in that window. The advantage of this method lies in the adaptive transmission rate correction based on local transmission rates, rather than a global uniform correction. This improves the accuracy of the correction. Due to the smoothing effect of the local window mean, the transmission rate correction is smoother, reducing potential edge artifacts and color block issues. By adaptively adjusting the transmission rate based on local means, this method effectively controls the correction magnitude, preventing the image from becoming overly bright or overexposed due to excessive correction. As a result, the correction becomes more adaptive, enhancing the quality of the dehazed image.

Design of transmission Estimation module based on local mean adaptation

In summary, we proposed novel calculation methods for estimating atmospheric light and transmission values. After accurately estimating these two parameters, they are substituted into the atmospheric scattering model to recover haze-free images. The design formula of the haze removal module is as follows:

In the above equation, A denotes the atmospheric light estimated by the ALETL module, t(x) represents the transmission estimated by the TELMA module, I(x) is the input image, and J(x) is the restored haze-free image.

Integrating the image enhancement module

To further enrich image details and enhance the dehazing effect, an image enhancement module is designed. First, wavelet denoising is applied to reduce image noise. Then, the dehazed image is converted from the RGB color space to the Lab color space, where the L channel (luminance channel) undergoes adaptive histogram equalization separately. The above processing does not affect color distribution, thereby avoiding the color distortion issues associated with traditional RGB histogram equalization. Additionally, a weighted fusion method is employed to moderately enhance contrast while preventing artifacts caused by excessive histogram equalization. Finally, the enhanced L channel is substituted back into the image, followed by conversion to the RGB color space. The structural diagram of the image enhancement process is shown in Fig. 4.

Integration of image denoising module

To enhance the quality of the dehazed image and reduce noise levels, guided filtering is applied as an additional processing step. Guided filtering43,44,45 is an edge-preserving filtering technique that utilizes a guidance image to perform smoothing while retaining crucial edge details in the image.

This method estimates the output pixels within local windows using a linear model, ensuring that the filtering result preserves the structure of the guidance image46. Compared to traditional methods such as Gaussian filtering, guided filtering offers the advantage of edge preservation and does not blur boundaries. Therefore, guided filtering was applied in the image enhancement module.

Experimental design of atmospheric light value Estimation

To achieve a more stable and accurate estimation of atmospheric light, a transfer learning-based atmospheric light estimation module was designed. The ITS subset of the RESIDE public dataset was employed as the training data, which contains a total of 13,990 synthetic hazy images. Among them, the first 12,990 images were used for training, while the remaining 1,000 images served as the test set. The ground-truth atmospheric light values for both the training and test sets were computed using a dedicated estimation method and stored as corresponding labels. This ensured a one-to-one correspondence between each hazy image and its true atmospheric light label. For the transfer learning-based atmospheric light estimation model, the maximum number of training epochs was set to 20, with each mini-batch consisting of 32 images. Each epoch involved 406 iterations, resulting in a total of 8,120 training iterations. The key parameters of the MobileNetV2 network are as follows: an expansion factor of 6, a width multiplier of 0.75, the Adam optimizer, an initial learning rate of 0.001, and a momentum value of 0.9. During the training process, the model’s loss and mean squared error (MSE) values were recorded at each iteration to assess convergence. The experiments were conducted on a hardware platform running Windows 11, equipped with a 14th Gen Intel® Core™ i9-14900HX CPU @ 2.20 GHz, 16.0 GB of RAM, and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4060 Laptop GPU with 8 GB GDDR6 memory. The software environment included PyCharm as the integrated development environment (IDE), Python version 3.11.11, and PyTorch as the deep learning framework. The loss and MSE curves during training are shown in Figs. 5 and 6.

As shown in Figs. 5 and 6, the atmospheric light value estimation model stabilizes around the 300th iteration, with the loss value approaching zero. This indicates that after the 300th iteration, the model’s prediction performance becomes stable, and the difference between the predicted and the true values is almost zero, signifying that the model has converged. From the RMSE curve, it can be observed that the difference between the model’s predicted values and the true values stabilizes after 1000 iterations, with the error value remaining below 0.1. This indicates that the model’s prediction error is small, and MobileNetV2 has successfully learned the pattern for atmospheric light value estimation, further confirming that the training process has reached convergence. To further verify whether the trained MobileNetV2 model can effectively predict real atmospheric light values, predictions were made on the test set, followed by performance testing. The results are shown in the following figures.

As shown in Fig. 7, the prediction errors for the vast majority of samples are relatively low, concentrated below 0.005, indicating that the model can accurately fit the true values in most cases. Figure 8 shows that the RMSE curve follows the same trend as the MSE, with the prediction errors for most samples being low. The RMSE curve shares the same dimensionality as the original data, making it a more intuitive reflection of the actual size of the prediction errors. Figure 9 shows the absolute error between the predicted and true values. Similar to the MSE curve, the majority of samples exhibit low MAE errors. Additionally, the MAE curve is less influenced by outliers and is more stable compared to the MSE curve. As shown in Fig. 10, the error distribution for all test samples is presented. The horizontal axis represents the error between the predicted and true values, while the vertical axis represents the number of samples. Most of the errors are concentrated around 0, displaying a relatively symmetric distribution. This indicates that the model does not exhibit any significant systemic bias (i.e., it does not overestimate or underestimate the atmospheric light value). The majority of errors fluctuate within the range of [−0.1, 0.1], with few extreme errors, suggesting that the model can accurately estimate the atmospheric light value in most cases. As shown in Fig. 11, the scatter plot between the true values and predicted values is presented. Ideally, all points should align along the diagonal. In the image, most of the predicted values are close to the true values, with data points clustering near the ideal fitting line, indicating that the model performs well overall. Except for a small number of predictions with some deviations when the true atmospheric light value is below 0.7, the majority of predicted values have a small error compared to the true values. As shown in Fig. 12, the variation curves of the true values (blue) and predicted values (red) for all test samples are displayed. The predicted values generally fit the true values well, with only a small number of predictions having some deviations from the true values. Overall, the model can estimate the atmospheric light values accurately in most cases, with only a small amount of data showing slight deviations. To further assess the testing performance, we calculated the overall average errors, including the overall average mean squared error (MSE), the overall average root mean squared error (RMSE), and the overall average mean absolute error (MAE). The results are shown in Table 1.

As shown in Table 1, the overall MSE is 0.0010536, indicating that the average squared error between the predicted and true values is very small. The model’s predictions are generally stable, with most samples showing small errors. There are a few extreme errors (outliers), suggesting that the model performs well in estimating atmospheric light values in various hazy environments. The overall MAE is 0.023229, which means the average error for each sample is 0.023229. MAE is a linear error metric, unlike the MSE curve, which amplifies the influence of extreme values. Therefore, MAE provides a more realistic reflection of the actual error. The current MAE value indicates that the error for the vast majority of samples is less than 0.023, demonstrating good stability in the predictions. The overall RMSE of the model is 0.03246, which means the standard deviation of the error is approximately 0.03246. RMSE shares the same unit as the original data, making it more interpretable than MSE, and it is well-suited for assessing the overall error level of the model. The current RMSE value suggests that the error fluctuation is small, indicating good model stability. If RMSE were significantly higher than MAE, it would suggest the presence of large outliers; however, since RMSE is only slightly higher than MAE, this indicates that the impact of extreme errors is not severe. Overall, the model demonstrates a good fit between predicted and true values and is capable of accurately estimating atmospheric light values.

To further verify the reliability of the proposed atmospheric light estimation model, we conducted comparative experiments using the EfficientNet-B0 model, which is currently a state-of-the-art atmospheric light estimation model known for its high accuracy and low parameter count. Experiments were performed on the same training and test sets, and the overall error performance was recorded. The results are presented in Table 2.

From the experimental results above, it can be observed that the three error metrics obtained using the EfficientNet-B0 model are relatively high. This indicates that the predicted atmospheric light values deviate more significantly from the ground truth when using this model. Overall, the proposed method demonstrates certain advantages, providing more accurate atmospheric light estimation and validating its reliability.

Image dehazing comparative experiment

To evaluate the dehazing performance and generalization ability of the proposed model, experiments were conducted on a self-constructed synthetic hazy dataset, the publicly available SOTS (Outdoor) dataset, and two real-world datasets: NH-HAZE and O-HAZE. The following sections describe the datasets and experimental settings in detail.

Datasets: The self-made synthetic hazy dataset contains 1,000 pairs of hazy and clear images. The clear images were sourced from the Cityscapes dataset and real-world collected images, while the hazy images were generated using an atmospheric scattering model by setting different β values to create hazy images with varying levels of haze intensity. Among them, images with β = 0.005 are considered as light haze images, images with β = 0.01 are considered as moderate haze images, images with β = 0.015 are considered as heavily hazy images, and images with β = 0.02 are considered as dense haze images. Each type of hazy image consists of 250 images. To test the dehazing performance of the proposed algorithm in outdoor bright areas, the SOTS (Outdoor) public dataset was selected, which contains 500 pairs of hazy and haze-free outdoor images. To validate the model’s dehazing performance in real-world hazy scenarios, tests were conducted on the publicly available NH-HAZE and O-HAZE datasets. The NH-HAZE dataset contains 55 pairs of real hazy and clear images, while the O-HAZE dataset includes 45 such pairs.

Experimental Parameter Settings: In the custom hazy dataset, both the original and haze-added images were uniformly resized to 620 × 480 pixels. Typically, the adaptive local mean window sizes for transmission estimation are selected from 20 × 20, 30 × 30, and 40 × 40. A smaller window size leads to an increased number of windows, which results in higher computational complexity, greater susceptibility to noise, and reduced smoothness. Conversely, a larger window size may fail to preserve image details and could result in the loss of local features. To balance dehazing accuracy and computational complexity, the adaptive local mean window size for transmission estimation was set to 30 × 30, resulting in a total of 336 windows. The experimental environments for the four hazy scenarios were consistent with those of the atmospheric light estimation module, with identical software and hardware configurations.

Dehazing comparison experiment based on self-made synthetic hazy dataset

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed model, we first conduct experiments comparing it with mainstream dehazing algorithms using the self-made synthetic hazy dataset. To more comprehensively and accurately evaluate the performance of dehazing models under varying haze conditions, we constructed a customized synthetic hazy dataset. Existing public datasets typically provide only coarse-grained categorizations of haze density. This limitation reduces their ability to assess a model’s adaptability and robustness across different scenarios, such as light, moderate, and heavy haze. In our dataset, haze levels are precisely defined and categorized into multiple grades, enabling more targeted and discriminative performance evaluation. Moreover, each hazy image is paired with a corresponding clear image, facilitating precise quantitative comparisons. The design of this dataset is grounded in the observation that haze concentration varies significantly in real-world applications, and a model’s effectiveness in practical deployment depends largely on its generalization ability across different haze levels. Therefore, conducting experiments on this dataset enables a more detailed characterization of model performance boundaries. It also provides reliable validation of the model’s practicality and robustness in complex real-world environments. The compared dehazing algorithms include image restoration-based methods, such as the DCP dehazing algorithm, as well as deep learning-based methods, including CoA dehazing25(Towards Real Image Dehazing via Compression-and-Adaptation, CVPR 2025), Dehamer dehazing27 (Image Dehazing Transformer with Transmission-Aware 3D Position Embedding, CVPR 2022), C2Pnet28 (Curricular Contrastive Regularization for Physics-Aware Single Image Dehazing, CVPR 2023), and DCMPNet30 (Depth Information Assisted Collaborative Mutual Promotion Network for Single Image Dehazing, CVPR 2024). The code for the above experimental models was obtained from publicly available open-source repositories. The experimental environment remained consistent with the previous setup. For the DTLMA algorithm, all parameters were normalized, the minimum filtering window size was set to 15, and a single-layer guided filter was applied for noise reduction. Some dehazing visualization results of these algorithms on our self-generated synthetic hazy dataset are shown in Fig. 13.

As shown in Fig. 13, the dehazed images processed by the DCP algorithm exhibit distortion in bright regions. The dark channel prior theory is not well suited for handling bright areas such as the sky, resulting in suboptimal dehazing performance in these regions. The CoA model produces dehazed images with generally good visual quality; however, some haze remains in the images, partially obscuring important details. The image processed by the Dehamer algorithm loses a significant amount of detail, resulting in color shifts and the loss of fine details. The dehazing effect achieved by the C2Pnet algorithm does not exhibit color shift problems, but there are still some areas in the hazy image where haze has not been fully removed. The dehazing result from the DCMPNet algorithm is relatively mild in terms of color distortion, and the dehazed image retains more of the original image’s details. However, there is still a noticeable difference compared to the original image. The dehazing result obtained using the DTLMA algorithm shows better visual effects. To further verify the differences among the dehazing algorithms, the performance of the results obtained by the above methods is evaluated, and the average values are calculated. The results are shown in Table 3.

According to the PSNR evaluation results, the dehazed images produced by the aforementioned algorithms generally exhibit values below 32 dB. The Dehamer algorithm shows relatively weaker performance, indicating that some noise remains in the processed images. In contrast, the DTLMA algorithm achieves better results, with a peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR) of 31.85 dB, demonstrating that images processed by the proposed method contain less noise and possess higher quality. Regarding the SSIM evaluation, the Dehamer algorithm performs the poorest, suggesting a noticeable difference between the processed images and the original ones. The results processed by the DTLMA algorithm demonstrate superior dehazing performance, with an average SSIM value reaching 91.90%. This indicates that the dehazed images produced by the proposed model are closest to the original images, exhibiting the lowest level of distortion. Additionally, the DTLMA algorithm achieves the best CIEDE2000 performance, indicating minimal color distortion and improved color restoration.

To enable locally adaptive adjustment of the transmission map, each input image (with a resolution of 620 × 480) was divided into multiple non-overlapping local windows of size 30 × 30. Since the image width of 620 is not divisible by the window size, zero-padding was applied to the right side of the image to extend its width to 630, allowing it to be evenly divided into 21 windows. As a result, each image was partitioned into 336 non-overlapping local windows, and transmission estimation and correction were performed separately for each window. To prevent padding pixels from introducing errors in local computations, the transmission values corresponding to the padded region were excluded from subsequent statistical and averaging operations, serving only to maintain the integrity of the window structure. To further validate the rationality and effectiveness of the selected number of windows, three commonly used window sizes were tested within the dehazing model. Experiments were conducted on a synthetic hazy dataset, and the dehazing performance is presented in Table 4.

According to the experimental results, different settings of the adaptive window size for computing the local mean of transmittance have varying impacts on model performance. When the window size is set to 30 × 30, the overall dehazing performance achieves a relatively good balance and shows clear improvement compared to the 20 × 20 window setting. The use of a 20 × 20 window may introduce noise during the patch-based dehazing process, potentially disrupting the spatial structure of the image, which results in suboptimal dehazing quality. When the window size is increased to 40 × 40, the noise level in the dehazed image is reduced, leading to improved visual quality. However, both SSIM and CIEDE2000 scores decline, indicating increased color distortion and structural deviation. Overall, a window size of 30 × 30 is the most appropriate choice, offering a good trade-off between visual quality and color accuracy.

Dehazing comparison experiments based on the SOTS (outdoor) dataset

The SOTS (Outdoor) dataset contains 500 pairs of hazy and clear outdoor images, with many of the outdoor images featuring bright areas such as the sky. This provides an ideal scenario for testing the model’s ability to effectively handle bright regions. To verify the effectiveness of the proposed algorithm, experiments were conducted on the SOTS (Outdoor) dataset. The visualization results are shown in Fig. 14 below.

The dehazing results obtained by the above models on the SOTS (Outdoor) dataset are similar to those on the custom foggy dataset. The DCP-based dehazing algorithm still introduces a certain degree of distortion. In contrast, the CoA algorithm consistently achieves good dehazing performance and effectively enhances image clarity. The results obtained using the Dehamer algorithm lost a significant amount of detailed information, which also affected the resolution of the dehazed image. The results obtained by applying the C2Pnet algorithm still show a certain degree of haze, which continues to obscure important information in the image. The DCMPNet and DTLMA algorithms, on the other hand, provided better dehazing visual effects, with no significant distortion observed in the bright regions of the image. To quantify the dehazing performance of each model, a performance evaluation of the dehazing results obtained from the above models was conducted. The average dehazing performance values are shown in Table 5.

Based on the above dehazing performance evaluation, the dehazed results obtained by the existing models generally exhibit noticeable noise, with average PSNR values mostly below 30 dB. This indicates that these models have relatively weak noise suppression capabilities. In contrast, the proposed algorithm achieves a PSNR of 30.21 dB, showing a clear advantage over other methods. Moreover, the average SSIM of the dehazed images produced by the proposed method reaches 90.86%, which also outperforms other mainstream dehazing algorithms. These experimental results verify the effectiveness of the proposed method. In terms of color fidelity, the CIEDE2000 evaluation shows that the DTLMA model achieves superior performance, with an average CIEDE2000 value of 2.82. This indicates significantly lower color distortion and better image quality compared to other models.

Dehazing comparison experiments based on the real-world NH-HAZE foggy image dataset

To validate the dehazing performance of the proposed algorithm in real-world scenarios, experiments were conducted on the NH-HAZE dataset. An image enhancement module and an additional image denoising layer were incorporated into the DTLMA algorithm, and the parameters within the DTLMA model were normalized. The dehazing results are shown in Fig. 15.

As observed from the above visualization results, the dehazing performance varies across the different methods. The DCP algorithm exhibits noticeable distortion in its dehazed outputs. Deep learning-based methods such as CoA, Dehamer, C2PNet, and DCMPNet often rely on synthetic hazy images for training, which leads to suboptimal performance when applied to real-world haze scenarios. These methods tend to suffer from color distortion and incomplete haze removal, indicating limited cross-dataset generalization ability. In contrast, the proposed algorithm achieves more satisfactory dehazing results. To quantitatively assess the performance of each model, evaluation metrics for the dehazed results are summarized in Table 6.

Based on the above performance evaluation results, most of the dehazing models exhibit noise robustness below 32 dB, indicating relatively weak denoising capabilities. In contrast, the proposed DTLMA algorithm achieves an average PSNR of 32.84 dB and an average SSIM of 85.25%, further validating its effectiveness. Among all evaluated models, the DTLMA algorithm consistently achieves the highest PSNR and SSIM across the three datasets, demonstrating both its effectiveness and superiority. The DTLMA algorithm achieved an average PSNR above 30 dB across all three hazy datasets, indicating strong noise robustness and good generalization performance. In terms of FADE evaluation, the DTLMA model produced the best results, suggesting that its dehazed images contain the least amount of residual haze and demonstrate the most effective dehazing performance.

Dehazing comparison experiments based on the real-world O-HAZE hazy image dataset

To further validate the dehazing performance of the proposed algorithm in real-world scenarios, additional experiments were conducted on the O-HAZE dataset. In this experiment, an image enhancement module and a single-layer denoising module were integrated into the DTLMA algorithm. Additionally, parameter normalization was applied within the DTLMA framework. The dehazing results are presented in Fig. 16.

As shown in the visual results in Fig. 16, the dehazing performance varies significantly across different methods. The image processed by the DCP algorithm exhibits noticeable distortion, and the haze is not effectively removed. The Dehamer algorithm demonstrates some improvement in haze removal; however, it introduces color shifts and residual distortion. The image produced by DCMPNet shows relatively better overall quality, yet still falls short in restoring fine details compared to the haze-free ground truth. The result from the C2PNet model retains a certain level of haze. In contrast, the CoA and DTLMA models yield comparatively better visual outcomes. To quantitatively evaluate the dehazing performance of each model, objective metrics were computed, and the results are presented in Table 7.

Based on the PSNR evaluation results, all the aforementioned models exhibit relatively poor noise resistance, with PSNR values generally below 30 dB. This further indicates that these dehazing methods struggle to suppress noise effectively, leaving residual noise that degrades the quality of the dehazed images. The DTLMA dehazing model, however, achieves an average PSNR of 33.56 dB, showing a clear advantage. In terms of SSIM and FADE metrics, the average SSIM reaches 90.52%, indicating that the proposed dehazing model provides the best restoration performance. These experimental results demonstrate the superiority of the proposed model and its strong generalization capability on real-world hazy datasets.

Ablation study

Ablation study of the ALETL module

To improve the accuracy of atmospheric light estimation, we designed the ALETL module to enhance the precision of atmospheric light values. To verify the effectiveness of the proposed method, we conducted step-by-step ablation experiments based on the DCP algorithm. Specifically, the traditional atmospheric light estimation module in DCP was replaced with the ALETL module. Both the original and modified models were evaluated on a synthetic hazy dataset, and the performance results are summarized in Table 8.

The results indicate that replacing the original module with the ALETL module has a significant impact on dehazing performance for synthetic hazy datasets. After integrating the ALETL module, both the PSNR and SSIM values improved, with a particularly notable enhancement in SSIM. These findings demonstrate that the introduction of the ALETL module effectively enhances the overall performance of the model, confirming the reliability of the proposed improvement.

Ablation study of the TELMA module

To improve the accuracy of transmission estimation and enhance dehazing performance in bright regions such as the sky, we designed the TELMA module to further refine the estimation of transmission values. To validate the effectiveness of the proposed method, we further replaced the original transmission module with TELMA based on the DCP algorithm already integrated with the ALETL module. Dehazing experiments and performance evaluations were conducted on a synthetic hazy dataset, and the results are shown in Table 9.

The results show that further replacing the module with TELMA on top of the ALETL integration leads to additional improvements in dehazing performance. These findings indicate that the introduction of the TELMA module helps enhance dehazing in bright regions such as the sky, reduces distortion in the dehazed images, and improves the overall visual quality. Moreover, the results validate the effectiveness of the TELMA module design.

Ablation study on image enhancement

To further verify whether the introduction of the image enhancement module can positively impact dehazing performance, we first performed image dehazing after estimating atmospheric light and transmission values. Subsequently, dehazing was conducted on the synthetic hazy dataset both with and without the image enhancement module. The visual comparison of dehazing results before and after enhancement is shown in Fig. 17.

The results above indicate that after image enhancement, the detail and edge information of the image become more pronounced, and the color restoration exhibits improved fidelity to the original image. For instance, in the second image, the windows and doors area shows enhanced color vibrancy and clearer details after image enhancement. This suggests that image enhancement helps to improve the visual quality of the dehazed image. To quantify the changes in dehazing performance, a performance evaluation of the images before and after enhancement was conducted, with the average performance values presented in Table 10.

Based on the above experimental results, after image enhancement, the SSIM performance of the dehazed images increased from an average of 89.92–91.01%. These results demonstrate that image enhancement can effectively improve the visualization of the dehazed images, further enhancing their visual quality beyond the original dehazing results, making the dehazed images closer to the original ones. At the same time, the noise in the dehazed images has been slightly amplified, with the average PSNR of the dehazed images decreasing from 32.19 dB to 31.56 dB. However, the image enhancement process has little effect on the model’s noise resistance, as the enhanced images maintain the model’s noise robustness while improving the visualization quality.

Image denoising ablation experiment

To further enhance the model’s denoising performance and improve the quality of the dehazed images, denoising processing is applied based on the previous image enhancement. Considering that the guided filtering algorithm has an edge-preserving effect, the guided filtering module is further integrated into the image enhancement process. The number of stacked guided filtering layers may have different impacts on the model’s denoising performance. To determine the appropriate number of guided filtering layers, one to six layers of the guided filtering algorithm are added on top of the previous image enhancement. The dehazing visual effects after incorporating guided filtering are shown in Fig. 18.

Based on the above dehazing results, it is concluded that integrating an appropriate denoising algorithm into the image enhancement process effectively reduces image noise. This integration improves the model’s anti-noise performance. When guided filtering modules with varying numbers of layers were incorporated, the dehazed images showed no significant changes in visual effects. Changes in color and detail restoration were also minimal. To quantify the dehazing performance with different numbers of guided filtering layers, a performance evaluation was conducted based on the image enhancement process. The results are shown in Table 11.

From the above experimental results, it can be seen that the dehazed image performance varies with the addition of different numbers of guided filter layers on top of the image enhancement. In terms of PSNR, as the number of guided filter layers increases, the model’s noise resistance performance improves, rising from 31.56dB to 32.04 dB. These results indicate that the integration of guided filtering effectively enhances the model’s noise resistance. In terms of SSIM performance, with the increase in the number of guided filter layers, the SSIM performance of the dehazed images gradually decreases. The highest SSIM average value was achieved after integrating just one layer of guided filtering. To simultaneously ensure robust noise suppression and high visual quality in the dehazing model, we introduce an additional guided filtering module on top of the aforementioned image enhancement process. This module is designed to remove residual noise present in the dehazed images, thereby improving the overall image quality. By combining image enhancement with guided filtering-based denoising, the original dehazing model achieves enhanced performance and delivers superior dehazing results.

Comparative experiments on dehazing efficiency

To evaluate the dehazing efficiency of the above models, their average inference times were measured on three synthetic and real-world hazy datasets: the Synthetic Hazy Dataset, SOTS (Outdoor) Dataset, and NH-HAZE Dataset. All experiments were conducted on an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4060 Laptop GPU with 8GB GDDR6 memory. The average inference times of these dehazing models on the three datasets are shown in Figs. 19, 20 and 21, and Fig. 22, respectively.

Figures 19, 20, 21 and 22 show that the DCP algorithm achieves the best dehazing efficiency and can perform fast dehazing in practical scenarios. However, it should be noted that DCP is not well suited for processing bright regions such as the sky in hazy images, where it causes severe distortions. Therefore, there is room for improvement in its visual dehazing quality. Overall, the CoA algorithm demonstrates good balance between dehazing quality and efficiency. The dehazing efficiency of the Dehamer and C2Pnet models still needs improvement. The DCMPNet algorithm achieves good overall dehazing performance and effectively removes haze to a large extent, but its inference speed is relatively low. The DTLMA algorithm shows strong dehazing performance across all four hazy datasets. Its dehazing speed is second only to the DCP model, while its overall dehazing quality surpasses other mainstream methods, indicating the proposed model’s advantages and practical application potential.

Conclusion

Currently, dehazing models do not perform well in handling bright areas and exhibit weak noise resistance, leading to distortion and poor noise resilience. To address these issues, a deep transfer learning and local mean adaptation-based image dehazing algorithm is proposed. This algorithm first employs a deep transfer learning-based method to estimate the atmospheric light value. By training a modified MobileNetV2 module, the algorithm comprehensively captures global image information, reducing computational errors and enhancing processing speed, thereby more stably and accurately estimating the atmospheric light value. Additionally, a local mean adaptation-based transmission map estimation module is designed, allowing the model to effectively handle both bright and non-bright areas of the image. Finally, image enhancement and denoising are applied to the dehazed images to improve the model’s noise resistance and its ability to capture edge details. To validate the effectiveness of the proposed algorithm, experiments were conducted on four different hazy datasets. The experimental results show that the proposed dehazing model performs well across all four hazy datasets, demonstrating a certain degree of generalization capability. Finally, to validate the dehazing efficiency of the proposed model, comparative experiments were conducted with mainstream algorithms on a synthetic hazy dataset. The results demonstrate that the proposed dehazing algorithm achieves good dehazing efficiency. This paper provides a novel dehazing method and approach for fields such as autonomous driving, contributing to advancements and developments in related areas.

Data availability

The RESIDE (ITS) and SOTS datasets that support the findings of this study are publicly available at https://sites.google.com/view/reside-dehaze-datasets/reside-standard. The NH-HAZE dataset that supports the findings of this study is publicly available at https://data.vision.ee.ethz.ch/cvl/ntire20/nh-haze/. The O-HAZE dataset that supports the findings of this study is publicly available at https://data.vision.ee.ethz.ch/cvl/ntire18/o-haze/.

References

LING, P. et al. Single image dehazing using saturation line prior[J]. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 32, 3238–3253 (2023).

CHEN W T et al. Sjdl-vehicle: Semi-supervised joint defogging learning for foggy vehicle re-identification[C]//Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. 36(1): 347–355. (2022).

Sakaridis, C., Dai, D. & Van Gool, L. Model adaptation with synthetic and real data for semantic dense foggy scene understanding[C]. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision. 687–704 (2018).

HUANG, F. et al. Active imaging through dense fog by utilizing the joint polarization defogging and denoising optimization based on range-gated detection[J]. Opt. Express. 31 (16), 25527–25544 (2023).

POLLAK, A. & MENON, R. Image-to-image machine translation enables computational defogging in real-world images[J]. Opt. Express. 32 (19), 33852–33860 (2024).

Rivera-Aguilar, B. A. et al. A new histogram equalization technique for contrast enhancement of grayscale images using the differential evolution algorithm[J]. Neural Comput. Appl. 36 (20), 12029–12045 (2024).

FAN, T. et al. An improved single image defogging method based on Retinex[C]//2017 2nd international conference on image, vision and computing (ICIVC). IEEE, : 410–413. (2017).

Wang, Y. et al. UCL-dehaze: Toward real-world image dehazing via unsupervised contrastive learning[J]. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 33, 1361–1374 (2024).

Xiao, J. et al. Single image dehazing based on learning of haze layers[J]. Neurocomputing. 389, 108–122 (2020).

Zhang, S. et al. Semantic-aware dehazing network with adaptive feature fusion[J]. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 53 (1), 454–467 (2021).

Ahmed, M., Li, X. & Tran, H. Multi-scale enhancement with pseudo-fog estimation for generalizable dehazing[J]. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 92, 104781–104793 (2023).

Chen, Z., He, Z. & Lu, Z.‑M. DEA‑Net: Single image dehazing based on detail‑enhanced convolution and content‑guided attention[J]. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 33, 1002–1015 (2024).

HE, K., SUN, J. & TANG, X. Single image haze removal using dark channel prior[J]. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 33 (12), 2341–2353 (2010).

Dong, H. et al. Multi-scale boosted dehazing network with dense feature fusion[C]. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 2157–2167 (2020).

Guo, C. L. et al. Image dehazing transformer with transmission-aware 3D position embedding[C]. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 5812–5820 (2022).

He, K. et al. Momentum contrast for unsupervised visual representation learning[C]. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 9729–9738 (2020).

Dong, J. & Pan, J. Physics-based feature dehazing networks[C]. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision. 188–204 (2020).

Liu, X. et al. GridDehazeNet: Attention-based multi-scale network for image dehazing[C]. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision. 7314–7323 (2019).

LIU, W. & ZHANG, J. Research on Image Defogging Algorithm Combining Homomorphic Filtering and Retinex[C]//2024 4th International Symposium on Computer Technology and Information Science (ISCTIS). IEEE, : 596–599. (2024).

HU, K. et al. A method for defogging sea fog images by integrating dark channel prior with adaptive Sky region Segmentation[J]. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 12 (8), 1255 (2024).

WANG, Y. et al. Adaptive Image-Defogging algorithm based on Bright-Field region Detection[C]//Photonics. MDPI 11 (8), 718 (2024).

TIAN, H. & YU X Y. Research on image defogging algorithm based on dark channel prior and particle swarm optimization[J]. J. Beijing Univ. Posts Telecommunications. 47 (2), 118 (2024).

GUAN, J., MA, M. & HUO, Y. Underwater polarimetric dark channel prior descattering[J]. Opt. Laser Technol. 175, 110864 (2024).

HAN, L. et al. Atmospheric scattering model and dark channel prior constraint network for environmental monitoring under hazy conditions[J]. J. Environ. Sci. 152, 203–218 (2025).

Ma, L. et al. Coa: Towards real image dehazing via compression-and-adaptation[C]//Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Conference. : 11197–11206. (2025).

LBAO, Z. H. A. N. G., SHAN, W. A. N. G. & XIAOHAN, W. A. N. G. Single image dehazing based on a bright channel prior model and a saliency analysis strategy. IET Image Proc. 15 (5), 1023–1031 (2021).

Guo, C. L. et al. Image dehazing transformer with transmission-aware 3D position embedding[C]. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 5812–5820 (2022).

Zheng, Y. et al. Curricular contrastive regularization for physics-aware single image dehazing[C]. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 5785–5794 (2023).

Wu, R. Q. et al. RIDCP: Revitalizing real image dehazing via high-quality codebook priors[C]. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 22282–22291 (2023).

ZHANG, Y. & ZHOU, S. LI H. Depth Information Assisted Collaborative Mutual Promotion Network for Single Image Dehazing[C]//Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. : 2846–2855. (2024).

Zheng, Y. et al. A novel image dehazing algorithm for complex natural environments[J]. Pattern Recogn. 157, 110865 (2025).

Huang, Y. et al. DCD-Net: weakly supervised decomposition learning for real-world image dehazing[J]. Sig. Process. 230, 109826 (2025).

Cui, Y. et al. EENet: an effective and efficient network for single image dehazing[J]. Pattern Recogn. 158, 111074 (2025).

Tran, L. A. & Park, D. C. Distilled pooling transformer encoder for efficient realistic image dehazing[J]. Neural Comput. Appl. 37 (6), 5203–5221 (2025).

Ma, T. et al. Polarimetric dual‑channel multi‑scale decomposition dehazing[J]. IEEE Sensors J. 25, 8569–8585 (2025).

Cong, X. et al. A semi-supervised nighttime dehazing baseline with spatial-frequency aware and realistic brightness constraint[C]//Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. : 2631–2640. (2024).

Yang, Y., Guo, C. L. & Guo, X. Depth-aware unpaired video dehazing[J]. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 33, 2388–2403 (2024).

Ren, J. et al. Triplane-smoothed video dehazing with clip-enhanced generalization[J]. Int. J. Comput. Vision. 133 (1), 475–488 (2025).

Du, Y. et al. Dehazing network: asymmetric UNet based on physical model[J]. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 62, 1–12 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. UCL-Dehaze: toward real-world image dehazing via unsupervised contrastive learning[J]. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 33, 1361–1374 (2024).

Stevens, T. S. W. et al. Dehazing ultrasound using diffusion models[J]. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 43 (10), 3546–3558 (2024).

Chougule, A. et al. Agd-net: attention-guided dense inception u-net for single-image dehazing[J]. Cogn. Comput. 16 (2), 788–801 (2024).

Dang, Y. et al. Efficient and adaptive recommendation unlearning: A guided filtering framework to erase outdated Preferences[J]. ACM Trans. Inform. Syst. 43 (2), 1–25 (2025).

Shen, Z. et al. IDTransformer: infrared image denoising method based on convolutional transposed self-attention[J]. Alexandria Eng. J. 110, 310–321 (2025).

Limami, F. et al. Fractional optimal control for deep convolutional neural networks exploring ODE-based solutions for image denoising[J]. Inverse Probl. Imaging. 19 (2), 424–455 (2025).

He, K., Sun, J. & Tang, X. Guided image filtering[J]. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 35 (6), 1397–1409 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China(Grant: 51977021) and Chongqing Graduate Student Research Innovation Program(Grant: CYB240245).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dongyang Shi: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing-original draft, Writing-review & editing. Sheng Huang: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, writing original draft, Writing-review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shi, D., Huang, S. Image dehazing algorithm based on deep transfer learning and local mean adaptation. Sci Rep 15, 27956 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13613-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13613-z