Abstract

Aortic stenosis (AS) is an important prognostic cardiovascular disease. However, there are few reports investigating the factors contributing to AS progression in patients with hemodialysis (HD). Because human arterial tissue can be easily harvested during arteriovenous fistula (AVF) surgery, we focused on the association between arterial calcification and AS progression. This is the first study with the aimed to establish a link between radial artery calcification (RAC) level and AS progression in patients with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD). All segments of the radial artery were collected during AVF surgery and stained with the Von Kossa stain. Changes in peak flow velocity (ΔVmax) were calculated based on two echocardiographic findings, and the relationship between RAC level and ΔVmax was analyzed. In the univariate analysis, RAC level, baseline peak aortic jet velocity (Vmax), and age were found to contribute to ΔVmax. After adjusting for age, sex, presence of diabetes, and Vmax at HD initiation, RAC level emerged as an independent factor contributing to ΔVmax. In conclusion, a high RAC level may be a predictor of subsequent development and progression of AS after HD initiation. Our findings may help identify this high-risk group and provide targeted healthcare interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Arteriosclerosis is an important risk factor for cardiovascular events in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in patients with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD). In fact, the cardiovascular mortality rate in hemodialysis (HD) patients is 10–20 times higher than in the general population1. This heightened risk is closely related to coronary artery disease and valvular heart disease2.

Aortic stenosis (AS) is one of the most common valvular diseases worldwide. In HD patients, the prevalence of aortic valve calcific abnormalities ranges from 28 to 85%, with severe AS detected in 6–13% of cases3. Additionally, the prevalence of AS and mitral regurgitation is higher in patients with CKD, including those not on dialysis4. ESKD is also associated with aortic and mitral valve calcification, accelerating the progression of valve stenosis and leading to worse outcomes5. Factors such as CKD-mineral and bone disorder, inflammation, anemia, hemodynamic changes, and volume overload contribute to the progression of AS3,6. The identification of valvular calcification on echocardiography has been reported to be independently associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes7. Aortic valve calcification increases the risk of cardiovascular mortality, even in the absence of significant obstruction of left ventricular outflow8. In patients with HD, calcified AS has also been identified as an independent risk factor for mortality9,10,11.

Patients with hemodynamically significant AS are vulnerable to episodes of profound hypotension on HD10, a condition known as dysdialysis syndrome, which can be life-threatening. In the same context, AS poses a significant challenge in managing patients on HD. AS progression plays a crucial role in the prognosis of patients with ESKD. However, there is limited research on the factors contributing to AS progression in dialysis patients, and no reports have explored the association between histological findings in arterial tissue and AS progression. Because human arterial tissue can be easily harvested during arteriovenous fistula (AVF) surgery in patients with HD, we focused on the associations of arterial calcification and changes in peak flow velocity (ΔVmax) with AS progression. According to clinical guidelines, peak aortic jet velocity (Vmax) is also used in the diagnostic criteria and severity classification of AS12. Generally, an increase in Vmax indicates the progression of stenotic changes of aortic valve, even before AS manifests clinically. Reportedly, Vmax gradually rises from the early stages of aortic valve sclerosis and accelerates over time, ultimately leading to the development of AS13.

As previously mentioned, CKD is associated with arteriosclerosis and AS. Hypothetically, patients with ESKD and arterial calcification are at a higher risk of developing AS.

In this study, we aimed to identify factors contributing to the progression of stenotic changes of aortic valve in patients with HD, including histological changes in peripheral arteries harvested at the time of AVF creation.

Results

Baseline characteristics

The clinical and laboratory baseline characteristics of the enrolled patients are presented in Table 1. The mean age at the time of AVF creation was 67.3 ± 13.6 years, with 37.2% of the participants (n = 35) being females. All patients had ESKD, with an average serum creatinine level of 8.46 ± 2.91 mg/dL and an estimated glomerular filtration rate of 5.7 ± 1.9 mL/min/1.73 m2. On baseline echocardiography, the average Vmax was 1.61 ± 0.45 m/s, and the average ΔVmax was 0.05 ± 0.27 m/s/year.

Histological findings

Microcalcifications were predominantly localized in the media (Fig. 1). These tissues were divided into three groups based on the first and second tertiles, with the first tertile at 0.017% and the second tertile at 0.256%.

Predictors of ΔVmax: univariate and multivariate analyses

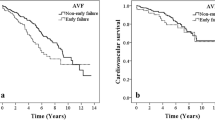

In the univariate analysis of clinical characteristics, cardiovascular risk factors, laboratory data, baseline Vmax, and RAC level, RAC level (adjusted mean of ΔVmax for severe group: 0.16 m/s/y, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.07–0.25 vs. for mild group: 0.02 m/s/y, 95% CI − 0.07–0.11 vs. for none group: − 0.03 m/s/y, 95% CI − 0.13–0.06; p = 0.01), baseline Vmax (standardized coefficients [β]: 0.21, 95% CI 0.09–0.33, p < 0.001), and age (β: 0.00, 95% CI 0.00–0.01, p = 0.02) were significantly associated with the increase in Vmax (Table 2). In the multivariate analysis of RAC level, baseline Vmax, age, and sex, RAC level (adjusted mean of ΔVmax for severe group: 0.14 m/s/y, 95% CI 0.04–0.23 vs. for mild group: 0.02 m/s/y, 95% CI − 0.07–0.11 vs. for none group: − 0.04 m/s/y, 95% CI − 0.13–0.05; p = 0.03) and baseline Vmax (β: 0.14, 95% CI 0.01–0.26, p = 0.03) were independent factors contributing to the increase in Vmax (Table 2). The relationship between ΔVmax and RAC level is shown in Fig. 2. Higher levels of RAC tended to result in greater increases in Vmax. Conversely, diabetes, serum phosphate, calcium, calcium–phosphate product, and parathyroid hormone levels were not associated with an increase in Vmax.

Factors associated with baseline Vmax

In the univariate analysis of clinical characteristics, RAC level (adjusted mean of baseline Vmax for severe group: 1.79 m/s, 95% CI 1.64–1.94 vs. for mild group: 1.48 m/s, 95% CI 1.33–1.63 vs. for none group: 1.56 m/s, 95% CI 1.40–1.71; p = 0.02) and age (β: 0.01, 95% CI 0.00–0.02, p = 0.01) were significantly associated with higher baseline Vmax (Table 3). In the multivariate analysis of RAC level, age, hemoglobin (Hb), phosphate, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, age (β: 0.01, 95% CI 0.00–0.02, p = 0.01) was an independent factor contributing to higher baseline Vmax. Although not statistically significant, higher rates of RAC tended to be associated with higher baseline Vmax (adjusted mean of baseline Vmax for severe group: 1.76 m/s, 95% CI 1.61–1.91 vs. for mild group: 1.51 m/s, 95% CI 1.36–1.65 vs. for none group: 1.56 m/s, 95% CI 1.41–1.71; p = 0.05; Table 3).

Factors associated with RAC level

In the univariate ordinal logistic regression analysis, only Hb level tended to be associated with RAC level (odds ratio: 0.74, 95% CI 0.54–1.01, p = 0.07). Even after adjustment for C-reactive protein level, corrected calcium level, and history of dyslipidemia, Hb level tended to be associated with RAC level (adjusted odds ratio: 0.75, 95% CI 0.54–1.03, p = 0.08), but there were no associations with all variables (Table 4).

Discussion

Our study revealed that elevated RAC level at the initiation of HD were associated with an increase in Vmax. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report to establish a link between RAC level and the progression of stenotic changes of aortic valve in patients with ESKD. Although many cases in this study did not meet the diagnostic criteria for AS, the significant increase in Vmax may serve as an indirect predictor of its future onset and progression. The results suggest that patients with ESKD and high RAC level are at a greater risk of AS development and progression. Therefore, these findings may help identify this high-risk group and provide targeted healthcare interventions. AS is a progressive disease with varying rates of progression among patients14, particularly dialysis patients. There is no consensus on the factors influencing AS progression in this population. Some studies suggest that annual echocardiography may be beneficial for monitoring moderate or asymptomatic AS in patients with ESKD15,16. However, current guidelines recommending fixed intervals for echocardiography based on population averages of AS17 may lead to unnecessary tests for slow-progressing patients and overlook significant progression in rapid-progressing patients18. The findings of our study may aid in administering appropriate healthcare strategies for patients with AS.

The most accurate method for evaluating vascular calcification (VC) is through histological examination of arterial specimens. While some studies have reported histological examinations of VC using rodent models like rats, there are limited reports on histological evaluation using human arterial tissues. Obtaining human artery tissues is typically challenging, but it can be easily done during AVF surgery19, allowing for the pathological evaluation of human arterial tissues.

It has been reported that RAC may be frequently associated with calcific coronary plaques20. In addition, there has been a correlation between coronary artery calcification and cardiac valve calcific deposits21. Aortic valve calcification is a precursor of AS22 and is involved in its development and progression. The risk of aortic valve calcification is linked to the baseline Agatston score of aortic valves23. While aortic valve calcification was traditionally attributed to time-dependent valve leaflet wear and passive calcium deposition, recent research suggests it is an active, multifaceted condition involving lipoprotein deposition, chronic inflammation, osteoblastic migration of valve interstitial cells (VICs), and active valve apex calcification24, in addition to passive processes. VC is also considered an active, regulated pathological process similar to osteogenesis, involving a phenotypic transition of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs)25. Valvular calcification is common in CKD and is closely associated with intimal arterial disease findings26. VICs, rather than VSMCs, populate the aortic valve. The pathogenesis of AS progression is distinct from that of atherosclerosis27. However, valvular calcification and VC may share common risk factors and pathogenetic features28. Our findings suggest that VC, common in CKD, and AS (aortic valve calcification) progression may be related, supporting this hypothesis.

It has been reported that baseline Vmax is a predictor of AS progression29. Another study indicated that calcified aortic valves and diabetes mellitus have been linked to rapid AS progression30. Some studies have also shown that serum phosphate, calcium, calcium–phosphate product, and parathyroid hormone levels can predict AS progression31,32. In addition, recent research suggests that warfarin use may be linked to AS progression33. However, conflicting reports exist, with some studies showing no correlation between these factors and AS progression in dialysis patients. The exact cause of the accelerated disease progression in this population remains unclear and is likely multifactorial9. In our study, as previously reported, it was suggested that baseline Vmax was related to AS progression, while factors such as diabetes mellitus, serum phosphate, calcium, and warfarin use were not found to be associated.

Aortic valve calcification increases as the estimated glomerular filtration rate decreases34. It has been reported that severe calcification in patients with ESKD actually begins long before renal insufficiency is severe enough to require dialysis35. The rate of progression of AS in dialysis patients is higher than in the general population6. In addition, decreased renal function may be associated with AS progression in nondialysis patients36. As just described, the degree of renal dysfunction is closely related to aortic valve calcification and the subsequent progression of AS. This study only included patients at the time of dialysis initiation; thus, we could study the progression of stenotic changes of aortic valve at the same level of renal function and duration of dialysis.

Currently, there are no pharmacotherapies that directly prevent the onset or progression of AS. In Japan, transcatheter aortic valve implantation for severe AS has been covered by insurance, even for dialysis patients, since February 2021. Therefore, surgical or transcatheter aortic valve implantation procedures are the only effective treatment options for severe AS in dialysis patients37. Early aortic valve replacement significantly improves 5-year survival compared to conservative treatment, even in dialysis patients38. Therefore, early detection of the onset and progression of AS and prompt treatment can improve the prognosis of these patients. For dialysis patients, there are no established standards regarding the intervals for echocardiography. Currently, the interval between echocardiography examinations after the initiation of dialysis varies from facility to facility. Patients with RAC may require more frequent follow-up echocardiography exams for the early detection of AS.

VC is commonly observed in patients with CKD and is often accompanied by abnormalities in phosphate and iron metabolism25,39. It has been reported that VC can develop in young adults with ESKD even in the absence of traditional cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension or dyslipidemia40. The mechanism of VC in CKD differs from classical arteriosclerosis (atherosclerosis). In this study, no significant factors contributing to arterial calcification were identified, including anemia, which is associated with CKD-MBD and classical arteriosclerosis risk factors. Anemia can lead to peripheral hypoxia, which in turn influences the osteogenic potential of bone cells41. It has been suggested that the hypoxia-inducible factor signaling pathway, which is the cellular response to hypoxia, potentially plays a role in the osteochondrogenic differentiation of VSMCs42. Low Hb level tended to be associated with RAC but it was not significant, thus this should be further studied.

This study has some limitations. First, the use of an AVF for HD access can impact cardiac load by increasing preload and decreasing afterload (peripheral vascular resistance)43, leading to high cardiac output and potentially elevating the transvalvular gradient in the setting of AS44. Second, the hemodynamic evaluation parameters of the aortic valve may be modified by the dialysis session36. While most assessments were conducted on nondialysis days in the majority of cases, the exact timing of these inspections was not always known. Third, because arterial specimens were harvested during AVF surgery, arterial specimens comprised only part of the artery opposed to representing cross-sections. This might affect the quantification of the RAC level. Moreover, it was difficult to collect a wide range of data on patients beyond echocardiography data after the initiation of HD, and therefore, we could not examine the impact of these data on ΔVmax. For instance, the control and treatment of CKD-MBD and anemia might have affected ΔVmax after initiation HD. However, our findings suggest that AS may progress more rapidly in cases with RAC, irrespective of the post-HD initiation scenario. Finally, because of the relatively short follow-up period and the limited sample size, progression to AS was observed in a few cases. Additionally, variability in follow-up durations across cases made the assessment of the absolute value of Vmax difficult. Therefore, evaluations were based on ΔVmax, adjusted for the follow-up interval.

We propose that an increase in Vmax may serve as an indirect predictor of AS onset and progression. However, a longer follow-up period and a larger sample size would be necessary to draw definitive conclusions regarding RAC as a predictor of AS development or progression.

In conclusion, RAC is an independent factor contributing to an increase in Vmax after HD initiation. Patients with ESKD and RAC should be aware of the potential development and progression of AS.

Methods

This study was performed as a subanalysis of the previous prospective trial. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Juntendo University Hospital, Tokyo, Japan (approval number 13-101) and registered at the clinical trials registry on 31/10/2013 (registration no. UMIN000012150). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (revised in Brazil in 2013), and informed consent was obtained from all participants, as approved by the ethics committee. The primary endpoint of this study was ΔVmax after initiation HD.

Patients

A total of 150 patients with ESKD underwent primary AVF surgery between November 2013 and April 2016 at Juntendo University Hospital, Tokyo, Japan. Exclusion criteria included insufficient sample of radial artery (n = 15), lack of echocardiography data or low left ventricular ejection fraction (n = 35), history of aortic valve surgery (n = 4), bicuspid aortic valve (n = 1), and aortic and/or mitral regurgitation (n = 1). Overall, 94 patients with ESKD were enrolled in the study. Baseline data for these patients at the time of AVF surgery were obtained from the institutional database.

Histological studies

All segments of the radial artery were collected during AVF surgery and immediately fixed in 10% neutral formaldehyde. The specimens were stained using the Von Kossa method to quantify calcium, which can detect microcalcifications. Slides were immersed in a 5% silver nitrate solution to replace calcium cations with silver, turning the mineralized material black. After being placed in 5% sodium thiosulfate, the specimens were counterstained with Kernechtrot for contrast, selectively staining nuclear chromatin red and providing nonspecific background tissue staining in shades of pink.

Sections stained with Von Kossa staining were captured as 20 × color images using an Olympus microscope (VS120-L100, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Histomorphometry was conducted using Definiens Tissue Studio software (Definiens, Munich, Germany). The area of Von Kossa-stained positive and the total arterial tissue were measured (Fig. 3), and the percentage of calcified tissue area to the total arterial tissue area was calculated for histologic quantitative evaluation. In case arterial tissue contained large amount of loose adventitial tissue, those sections were excluded (Fig. 3).

Methods of histomorphometry of radial artery calcification using software. (a) The region enclosed in orange represents the total arterial tissue (the loose adventitial tissue was excluded). (b) The calcium-stained area is indicated by yellow area, which corresponds to the Von Kossa-stained positive area.

Echocardiography

These patients underwent echocardiography immediately before AVF surgery, and at least one echocardiography was performed within 5 years of initiating HD. The patients were examined in a left lateral decubitus position using the LOGIQ e ultrasound system (GE Healthcare Japan, Tokyo, Japan). The exam included a comprehensive assessment of cavity and wall dimensions, ventricular and valvular function, morphologic appraisal, and pressure predictions, following international guidelines. Vmax was routinely measured using continuous-wave Doppler tracing, recorded from the window yielding the highest velocity signal. The progression between the first and last exams was expressed as a Vmax change. To account for interindividual variations in the follow-up interval, the change in peak flow velocity was normalized to a 1-year interval. The Vmax data immediately before AVF surgery was defined as baseline Vmax, and the change in Vmax per year was defined as ΔVmax.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation for the normally distributed data or median and interquartile ranges for the skewed data, while categorical data were presented as numbers and percentages. For the evaluation of radial artery calcification (RAC), the tissues were categorized into three groups based on the degree of RAC: none, mild, and severe RAC groups by the first and second tertiles (Fig. 1).

First, univariate analysis was conducted using simple linear regression for continuous covariates or one-factorial analysis of variance for categorical factors to identify relevant factors potentially influencing ΔVmax (factors with a p value of 0.2 or less). These factors, along with sex, were included in the multivariate analysis as covariates.

Second, a multivariate analysis was performed to investigate the impact of the parameters on ΔVmax. Multivariate analyses using analysis of covariance for categorical variables or multiple linear regression for continuous variables were conducted, and RAC level, sex, diabetes mellitus, baseline Vmax, and age were selected as covariates.

In addition, factors associated with baseline Vmax were examined using analysis of covariance for categorical variables or multiple linear regression for continuous variables, while the degree of RAC was analyzed using ordinal logistic regression.

All statistical analyses were conducted using the Windows version of JMP software (Version 17.0.0, SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC), with a significance level set at a p value of < 0.05.

Data availability

The data used in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Foley, R. N., Parfrey, P. S. & Sarnak, M. J. Clinical epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in chronic renal disease. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 32, S112–S119 (1998).

Ahmad, Y., Bellamy, M. F. & Baker, C. S. R. Aortic Stenosis in dialysis patients. Semin. Dial. 30, 224–231 (2017).

Rattazzi, M. Aortic valve calcification in chronic kidney disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 28, 2968–2976 (2013).

Samad, Z. et al. Prevalence and outcomes of left-sided valvular heart disease associated with chronic kidney disease. JAHA 6, 6044 (2017).

Patel, K. K. et al. Characteristics and outcomes of patients with aortic stenosis and chronic kidney disease. JAHA 8, 9980 (2019).

Perkovic, V., Hunt, D., Griffin, S. V., Du Plessis, M. & Becker, G. J. Accelerated progression of calcific aortic stenosis in dialysis patients. Nephron. Clin. Pract. 94, c40–c45 (2003).

Raggi, P. et al. All-cause mortality in hemodialysis patients with heart valve calcification. CJASN 6, 1990–1995 (2011).

Otto, C. M., Lind, B. K., Kitzman, D. W., Gersh, B. J. & Siscovick, D. S. Association of aortic-valve sclerosis with cardiovascular mortality and morbidity in the elderly. N. Engl. J. Med. 341, 142–147 (1999).

Zentner, D. et al. Prospective evaluation of aortic stenosis in end-stage kidney disease: A more fulminant process?. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 26, 1651–1655 (2011).

London, G. M., Pannier, B., Marchais, S. J. & Guerin, A. P. Calcification of the aortic valve in the dialyzed patient. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 11, 778–783 (2000).

Minamino-Muta, E. et al. Causes of death in patients with severe aortic stenosis: An observational study. Sci. Rep. 7, 14723 (2017).

Izumi, C. et al. JCS/JSCS/JATS/JSVS 2020 guidelines on the management of valvular heart disease. Circ J. 84, 2037–2119 (2020).

Kurasawa, S. et al. Relationship between peak aortic jet velocity and progression of aortic stenosis in patients undergoing hemodialysis. Int. J. Cardiol. 402, 131822 (2024).

Amanullah, M. R. et al. Factors affecting rate of progression of aortic stenosis and its impact on outcomes. Am. J. Card. 185, 53–62 (2022).

Lentine, K. L. et al. Cardiac disease evaluation and management among kidney and liver transplantation candidates: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology Foundation: Endorsed by the American Society of Transplant Surgeons, American Society of Transplantation, and National Kidney Foundation. Circulation 126, 617–663 (2012).

Rosenhek, R. et al. Predictors of outcome in severe, asymptomatic aortic stenosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 343, 611–617 (2000).

Otto, C. M. et al. 2020 ACC/AHA Guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 143, e35–e71 (2020).

Lindman, B. R. Progression rate of aortic stenosis: Why does it matter?. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 16, 329–331 (2023).

Kano, T. et al. Impact of transferrin saturation and anemia on radial artery calcification in patients with end-stage kidney disease. Nutrients 14, 4269 (2022).

Achim, A. et al. Radial artery calcification in predicting coronary calcification and atherosclerosis burden. Cardiol. Res. Pract. 2022, 1–8 (2022).

Wang, A.Y.-M. et al. Cardiac valve calcification as an important predictor for all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality in long-term peritoneal dialysis patients: A prospective study. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 14, 159–168 (2003).

Kurasawa, S. et al. Number of calcified aortic valve leaflets: natural history and prognostic value in patients undergoing haemodialysis. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 24, 909–920 (2023).

Owens, D. S. et al. Incidence and progression of aortic valve calcium in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). Am. J. Cardiol. 105, 701–708 (2010).

Lindman, B. R. et al. Calcific aortic stenosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2, 16006 (2016).

Ye, Y. et al. Repression of the antiporter SLC7A11/glutathione/glutathione peroxidase 4 axis drives ferroptosis of vascular smooth muscle cells to facilitate vascular calcification. Kidney Int. 102, 1259–1275 (2022).

Leskinen, Y. et al. Valvular calcification and its relationship to atherosclerosis in chronic kidney disease. J. Heart Valve Dis. Jul. 18, 429–438 (2009).

Dweck, M. R., Boon, N. A. & Newby, D. E. Calcific aortic stenosis: A disease of the valve and the myocardium. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 60, 1854–1863 (2012).

Moe, S. M. et al. Medial artery calcification in ESRD patients is associated with deposition of bone matrix proteins. Kidney Int. 61, 638–647 (2002).

Otto, C. M. et al. Prospective study of asymptomatic valvular aortic stenosis clinical, echocardiographic, and exercise predictors of outcome. Circulation 95, 2262–2270 (1997).

Nishimura, S. et al. Predictors of rapid progression and clinical outcome of asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis. Circ. J. 80, 1863–1869 (2016).

Ureña, P. et al. Evolutive aortic stenosis in hemodialysis patients: Analysis of risk factors. Nephrol. 20, 217–225 (1999).

Pawade, T. A., Newby, D. E. & Dweck, M. R. Calcification in aortic stenosis: the skeleton key. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 66, 561–577 (2015).

Hariri, E. H. et al. Impact of oral anticoagulation on progression and long-term outcomes of mild or moderate aortic stenosis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 80, 181–183 (2022).

Guerraty, M. A. et al. Relation of aortic valve calcium to chronic kidney disease (from the chronic renal insufficiency cohort study). Am. J. Cardiol. 115, 1281–1286 (2015).

Merjanian, R., Budoff, M., Adler, S., Berman, N. & Mehrotra, R. Coronary artery, aortic wall, and valvular calcification in nondialyzed individuals with type 2 diabetes and renal disease. Kidney Int. 64, 263–271 (2003).

Candellier, A. et al. Chronic kidney disease is a key risk factor for aortic stenosis progression. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 38, 2776–2785 (2023).

Nishimura, R. A. et al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 63, e57–e185 (2014).

Bohbot, Y. et al. Severe aortic stenosis and chronic kidney disease: outcomes and impact of aortic valve replacement. JAHA 9, 17190 (2020).

Zarjou, A. et al. Ferritin prevents calcification and osteoblastic differentiation of vascular smooth muscle cells. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 20, 1254–1263 (2009).

Goodman, W. G. et al. Coronary-artery calcification in young adults with end-stage renal disease who are undergoing dialysis. N. Engl. J. Med. 342, 1478–1483 (2000).

Mokas, S. et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 plays a role in phosphate-induced vascular smooth muscle cell calcification. Kidney Int. 90, 598–609 (2016).

Copur, S., Ucku, D., Cozzolino, M. & Kanbay, M. Hypoxia-inducible factor signaling in vascular calcification in chronic kidney disease patients. J. Nephrol. 35, 2205–2213 (2022).

Aala, A., Sharif, S., Parikh, L., Gordon, P. C. & Hu, S. L. High-output cardiac failure and coronary steal with an arteriovenous fistula. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 71, 896–903 (2018).

Ennezat, P. V., Maréchaux, S. & Pibarot, P. From excessive high-flow, high-gradient to paradoxical low-flow, low-gradient aortic valve stenosis: Hemodialysis arteriovenous fistula model. Cardiology 116, 70–72 (2010).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank members of the Laboratory of Morphology and Image Analysis, Biomedical Research Core Facilities, Juntendo University Graduate School of Medicine for technical assistance with microscopy.

Funding

This study was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (Grant No.: JP21K11199; to J. Nakata).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.M., J.N., and H.I. developed concepts for this study. T.M., T.K., H.F., and K.S. collected data. T.M. and S.N. analyzed the results. T.M. drafted the manuscript. T.M., J.N., H.I., and Y.S. revised the manuscript. All authors gave their approval for the final version to be submitted.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Maeda, T., Nakata, J., Nojiri, S. et al. Radial artery calcification is a predictor of aortic stenosis development and progression after initiation of hemodialysis. Sci Rep 15, 30350 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13644-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13644-6