Abstract

Insight problem-solving is a creative cognitive process that involves overcoming mental impasses and discovering novel solutions. However, the neural mechanisms underlying insight, particularly in spatial manipulation task remain poorly understood. In this study, we investigated the brain dynamics involved in solving matchstick arithmetic problems, a type of spatial insight problem, using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). We applied two complementary analysis methods: (1) a general linear model (GLM) to identify brain regions associated with different problem-solving strategies (quick, analytical, and insight-based solutions), and (2) a hidden Markov model (HMM) to estimate discrete brain states during the problem-solving process. Our findings reveal that the default mode network (DMN) was more active during insight-based solutions than during quick and analytical strategies, whereas the executive control network (ECN) exhibited increased activation during quick and analytical solutions. These results suggest distinct roles for the DMN and ECN in spatial insight problem-solving. Additionally, we characterized specific brain states for each problem-solving strategy using HMM and examined their relationships with behavioral performance and state transitions. Our results suggest that insight problem-solving involves dynamic interactions between large-scale brain networks, with different strategies corresponding to different brain states. Notably, the high variability in brain state dynamics observed during the prolonged process of insight solutions may reflect increased cognitive flexibility. This study offers novel insights into the neural basis of spatial insight and its temporal dynamics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Creative insight is a well-recognized phenomenon in human cognition, famously illustrated by the story of Archimedes, who discovered a method to determine the density of a crown while sitting in a bathtub. Wallas conceptualized creative cognition as a four-step sequential process: preparation, incubation, illumination, and verification1. An alternative framework, the “Geneplore” model, proposes that creative problem-solving involves iterative cycles of generative and exploratory processes, continuing until a satisfactory solution emerges2,3. Both models suggest that dynamic brain states underlie the creative-problem-solving process.

Jung-Beeman et al.4 characterized four key aspects of creative insight: (i) problem solvers initially reach an impasse, halting progress toward a solution; (ii) the process leading to a breakthrough is often subconscious and cannot be explicitly described by the solver; (iii) solutions appear suddenly, and solvers instantly recognize their correctness; and (iv) solving insight problems involves creative thinking and cognitive skills distinct from those required for non-insight problems. We hypothesized that dynamic brain states play a crucial role in solving complex problems.

The right anterior temporal lobe (ATL) and left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) have been implicated in insight problem-solving4,5. These regions are activated during insight tasks, and transcranial electric stimulation, such as transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), targeting these areas has been shown to enhance performance on such tasks6,7,8,9,10,11,12. Neuroimaging studies, including those using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), reveal increased right ATL activity during insight-problem solving compared to non-insightful problem-solving, which is without the ”Aha!” experience4. Additionally, the left DLPFC, along with subcortical regions such as the nucleus accumbens, hippocampus, and dopaminergic midbrain, has been linked to the intensity of the subjective “Aha!” experience. Dynamic causal modeling (DCM) analysis has revealed that the left DLPFC is positively connected to the nucleus accumbens and negatively connected to the hippocampus during high-insight solutions5. Intervention studies using tDCS have shown that electrical stimulation of the DLPFC or right ATL enhances performance on various insight tasks6,7,9,11,12,13. These findings suggest that tDCS-induced changes in brain state may improve insight problem-solving, but the underlying dynamics remain poorly understood.

Recent analyses aimed at quantifying dynamic brain states have employed the hidden Markov model (HMM) and functional connectivity to capture the temporal evolution of large-scale brain networks, offering greater ecological applicability than traditional task designs14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23. These methods are effective for characterizing the dynamic interactions between brain regions during tasks involving significant variability in response time, such as insight problem-solving. Unlike the general linear model (GLM), which can localize brain regions associated with a task but cannot evaluate dynamic interactions, the HMM can detect stable and abstract event boundaries even during complex cognitive processes.

In this study, we used HMM profiles to characterize the dynamic brain states associated with insight problem-solving. We acquired fMRI data at rest and during an insight problem-solving task across three scanning sessions, focusing on the matchstick arithmetic (MA) task (Fig. 1), which requires spatial manipulation to solve equations rather than verbal insight tasks such as the Remote Associates Test (RAT). After each trial, the participants were instructed to annotate their solutions as “Quick,” “Analytical,” or “Insight.” We estimated the dynamic brain state profiles using HMM (Fig. 2) and quantified them according to each type of solution.

Experimental paradigm of matchstick arithmetics (MA). Design of the MA task: Participants were instructed to solve an MA by correcting an equation through moving a single matchstick during the ‘Question’ phase (maximum duration: 240 s). If a participant found a solution, they pressed a button with their index finger ([1] answer) and selected an answer from three options during the ‘Response for the answer’ phase: [1] and [2]: numbers or [3]: other. If the correct answer was [1] or [2], the participant selected the appropriate number; otherwise, they selected [3]. Afterward, the participant indicated the method of solution: [1] quick solution, [2] analytical solution, or [3] insight solution. Finally, the participant rated the difficulty of the task as [1] easy or [3] difficult. If the participant did not answer within the maximum duration or selected ‘skip’ during the ‘Question’ phase, the program displayed ‘Fixation’ and moved to the next trial.

Mean activations of brain states. Mean activation maps of the nine brain states estimated using the hidden Markov model (HMM). Each state’s mean activation is color-coded, ranging from low (blue) to high (red). In the plot (bottom right), the y-axis represents the average correlations between each HMM model and 14 other models, calculated using the Munkres (Hungarian) algorithm. The x-axis represents the model number, as 15 models were generated iteratively. The model with the highest correlation (red circle) aligns with the labeled states across other models, leading to the selection of model #6 for this study. Abbreviations: dDMN, dorsal default mode network; PRE, precuneus; vDMN, ventral default mode network; ASN, anterior saliency network; PSN, posterior saliency network; LECN, left executive control network; RECN, right executive control network; BGN, basal ganglia network; AUD, auditory network; pVIS, primary visual network; hVIS, high visual network; SMN, sensorimotor network; VSN, visuospatial network; LAN, language network.

Results

Solution-specific brain activity

The number of solution strategies reported by the participants is presented in Table 1. Over the three-session experiment, we collected a total of173.8 ± 8.7 responses, consisting of quick solutions (105.4 ± 22.8), analytical solutions (45.9 ± 15.8), and insight solutions (8.4 ± 5.5). One participant (Participant #8) was excluded from further analyses (GLM and HMM statistics) because of the absence of any insight solution responses. The hit rates showed the following accuracies for each solution type: quick solutions: 97.9 ± 1.8%; analytical solutions: 96.7 ± 4.1%; and insight solutions: 78.6 ± 27.8%.

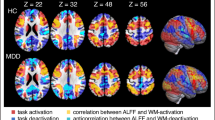

We compared the mean RTs for quick (8.61 ± 1.9 s), analytical (36.58 ± 13.7 s), and insight solutions (114.44 ± 29.6 s) (Fig. 3a). Tables 2, 3, and 4 present the statistical results of the GLM comparisons. First, we contrasted insight with analytical solutions (insight > analytical: Fig. 3b; insight < analytical: Fig. 3c). In the “insight > analytical” contrast, significant clusters were identified in the left superior frontal gyrus 2 (SFG2), right angular gyrus, left superior temporal gyrus (STG), left angular gyrus, right middle cingulate cortex (MCC), right posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), right superior temporal pole (STP), left precuneus, and right insula. Conversely, in the “analytical > insight” contrast, significant clusters were found in the left middle occipital gyrus (MOG), left thalamus, right middle frontal gyrus 2 (R MFG2), left insula, and right insula. Brain regions identified in the contrast (insight > analytical) included the right STP and left SFG2, consistent with previous findings, such as the right ATP (Jung-Beeman et al., 2003) and the left DLPFC5, respectively.

Behavioral results and activation maps resulting from general linear model (GLM) analysis. (a) Mean response time for each solution type. (b–g) GLM results. The threshold for statistical significance was set at an uncorrected p value of 0.001, with a cluster-based family-wise error (FWE) correction applied at a p value < 0.05. The following contrasts are shown: (b) insight > analytical (k > 270 voxels); (c) insight < analytical, (k > 494 voxels); (d) insight > quick, (k > 228 voxels); (e) insight < quick, (k > 307 voxels); f: analytical > quick, (k > 449 voxels); g: analytical < quick, (k > 1487 voxels).

Subsequently, we compared the contrasts between insight and quick solutions (insight > quick: Fig. 3d; insight < quick: Fig. 3e). In the “insight > quick” contrast, significant clusters were identified in the left medial superior frontal gyrus (mSFG), right angular gyrus, left angular gyrus, right precuneus, left caudate, right inferior frontal gyrus (IFG), right inferior frontal gyrus triangular part (IFG tri), and bilateral middle temporal gyrus (MTG). In the “insight < quick” contrast, significant clusters were found in the left MOG, left inferior frontal gyrus orbital part (IFG orb), bilateral MFG 2, left inferior parietal lobule (IPL), and left mSFG.

Additionally, we compared the contrasts between the analytical and quick solutions (analytical > quick: Fig. 3f; analytical < quick: Fig. 3g). The “analytical > quick” contrast revealed significant clusters in the right supramarginal gyrus, left IFG orbital part 2 (IFG orb 2), bilateral MFG 2, left IPL, and left mSFG. In the “analytical < quick” contrast, significant clusters were found in the bilateral paracentral gyri and right postcentral gyrus.

These findings suggest that brain regions associated with broader networks, including the dorsal default mode network (dDMN) and language network (LAN), are more activated during the insight solution than the analytical and quick solutions. Conversely, brain regions associated with the executive control network (ECN) and visual network (higher visual network; hVIS, primary visual network: VIS) exhibit greater activation during analytical and quick solutions than during insight solutions. The mean time courses of the BOLD signal at the peak voxel for each cluster of the contrasts are shown in Supplementary Fig. 5.

Dynamic brain states estimated from the HMM

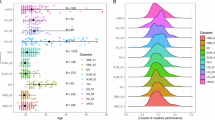

The mean activation patterns (mean of the Gaussian distribution) for each brain state were estimated using HMM, as shown in Fig. 2. To explore the functional characteristics of these brain states, we compared the FO across three solution types: the quick solution included whole periods, and the analytical and insight solutions analyzed for approximately 9 s prior to the response. We performed paired t-tests for each solution type (Fig. 4). For the quick solutions, we observed a significantly higher FO for States 2, 6 and 8 compared to both the analytical and insight solutions. In the analytical solution, the FO of State 9 was significantly higher than in both the quick and insight solutions. Regarding the insight solution, FOs of States 4 and 5 were significantly higher than in the quick and analytical solutions.

Comparison of fractional occupancy (FO) for dynamic brain state profiles across solution strategies. In each state, we compared FOs across three strategies (quick, analytical, and insight). Asterisks indicate statistical significance based on one-way ANOVA (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.005, with Tukey–Kramer honestly significant difference post-hoc test). The boxplots represent the 25th and 75th percentiles (upper and lower edges), the central line indicates the median, and the dots represent individual participants.

To examine the differences in long-term processes, we conducted a post hoc analysis by visualizing the dynamic brain states across participants for the analytical (Fig. 5b) and insight (Fig. 5c) solutions. For the mean RT of the analytical solution, described in Subsection “Solution-specific brain activity,”, we aggregated all trials where the analytical and insight solutions lasted longer than 30 s for each participant and mapped the brain states during the “Fixation” phase (rest) and the final 30 s of problem-solving in the “Question” phase. The brain states during the “Fixation” phase exhibited similar temporal patterns in both solutions, primarily involving states 3 (yellow) and 6 (bright blue). In the analytical solution, states 9 and 5 were predominant during the 30 s before participants responded in the “Question” phase. In contrast, the insight solution exhibited a variety of brain states, such as states 1, 2, 4, 5, and 9, with temporal patterns that varied across participants, consistent with the state transition graph shown in Fig. 5a. To quantify state transition variability across the three conditions—rest (inter-trial-interval), insight solution, and analytical solution—we computed the entropy using the bootstrapping method (Supplementary Fig. 4). We found a significantly higher entropy for the insight solution (1.70 ± 0.04) than for both the rest (1.16 ± 0.05) and the analytical solution (1.14 ± 0.04). This indicates that brain states during the last 30 s of the “Question” phase exhibited more flexible dynamics in the insight solution. These results suggest that temporal brain state dynamics differ depending on the problem-solving strategy, while resting brain dynamics exhibit similar temporal patterns, indicating that participants may switch cognitive processes during insight problem-solving.

Properties of dynamic brain states depending on solutions. (a) Directed graphs represent state transition probabilities (ST) for each solution compared with the resting state. Dark red lines with greater width indicate higher ST. (b, c) Brain states are color-coded according to the legend (right side) for both the Fixation phase, before the Question phase began, and the final 30 s of the Question phase, just before the response. Brain states in rest are similar across participants in both solutions. However, states 5 and 9 dominated the analytical solution, while multiple brain states appeared in the insight solution.

Discussion

In this study, we aimed to characterize brain state dynamics during insight problem-solving in the MA task using both GLM and HMM. GLM analysis revealed distinct activation patterns associated with different problem-solving strategies: the dDMN showed higher activation in the insight solution than in the quick and analytical solutions, whereas the bilateral ECN and VSN exhibited higher activation in the quick and analytical solutions than in the insight solution. HMM analysis further identified specific brain states associated with each strategy: States 4, and 5 were linked to insight solutions; State 9 to analytical solutions; and states 2, 6, and 8 to quick solutions. These findings suggest that dynamic brain states vary depending on the problem-solving strategies employed. Below, we discuss four key points: (i) differentiation in brain networks, (ii) temporal dynamics and flexibility, (iii) roles of specific brain states, and (iv) a comparison of psychological models for insight problem-solving.

Differentiation in brain networks

GLM analysis revealed distinct activation patterns across different problem-solving strategies. We also demonstrated temporal changes in BOLD signals at the peak voxels, which varied depending on the contrasts (Supplementary Fig. 5). For the “insight > analytical” contrast, we found that the right ATL and DLPFC were included in the identified clusters, consistent with previous findings on verbal insight4,5. Furthermore, the specific clusters identified for this contrast included the dDMN, PSN, LAN, and AUD (Table 2). For the “insight > quick” contrast, we observed activity in the dDMN and LAN (Table 3). Specifically, the dDMN and LAN (including the bilateral angular gyrus) exhibited greater activation during the insight solution, whereas the ECN and VIS showed increased activity during both quick and analytical solutions. These results suggest that different cognitive processes are involved in these strategies, highlighting the importance of broader network interactions rather than limited brain regions or a single network. The engagement of the dDMN likely reflects introspective and spontaneous thought processes. Meanwhile, the LAN, including the bilateral angular gyrus, may be associated with multisensory integration and semantic processing, which are crucial for mathematical thinking, such as a core component of insight problem-solving. Conversely, the activation of the ECN and VIS appears to support the deliberate, stepwise visual search processing characteristic of analytical thinking.

Our findings indicate that heightened activity in the sensorimotor areas was observed for quick solutions, suggesting that this solution may be driven by automatic processes in subcortical regions. This aligns with the concept of intuitive processing, as seen in expert Shogi players24, or observed in verbal insight incorporating semantic priming with "Aha!" experience25, where repeated task exposure leads to fast, nearly automatic responses.

Temporal dynamics and flexibility of brain states and their roles

HMM analysis provides insights into the functional roles of various brain states. We identified nine brain states with distinct mean activation patterns, each suggesting specific functional interpretations: State 1 involved internal processing; State 2 reflected bottom-up sensory processing; State 3 related to sensory integration and attention; State 4 was associated with salience and external demands; State 5 showed coactivation of the DMN, salience network (SN), and ECN; State 6 involved coactivation of DMN, ECN and LAN; State 7 was linked to multisensory processing; State 8 pertained to language-related processes; and State 9 was involved in intuitive execution processes.

Significant differences in temporal brain-state dynamics were observed between the insight and analytical solutions. Using the concepts of in-degree (number of incoming edges) and out-degree (number of outgoing edges) to quantify “hub” status, we characterized states with more than six connections:

-

In the analytical solution, States 2, 5, and 9 were identified as hubs.

-

In the insight solution, States 2, 4, and 5 were identified as hubs.

State 5 consistently exhibited high in- and out-degrees in both solutions, indicating its flexibility. This suggests that it acts as a central connector for both incoming and outgoing transitions, which is important for long-term thinking. Conversely, State 9 in the analytical solution (showing significantly higher FO than the other two solutions in Fig. 4), and State 2 in the insight solution showed a higher in-degree than their out-degree. This imbalance suggests that these states might represent more stable or less exploratory cognitive processes, where transitions primarily flow in rather than out. These findings highlight both commonalities and differences in dynamic brain states between the analytical and insight problem-solving strategies, particularly during prolonged problem-solving periods (longer than 30 s).

Previous studies using GLM localized specific brain regions related to insight problem-solving, such as the right ATL4 and left DLPFC5, but did not address large-scale brain interactions. However, our study demonstrated that the analytical solutions predominantly involved states 5 and 9, while insight solutions engaged a broader range of brain states, including states 1, 2, 4, 5, and 9, reflecting a more diverse cognitive process.

Focusing on the insight solution, States 4 and 5, which involved the coactivation of the DMN, ECN, and SN, played a central role. Evidence for this includes its higher variance in FO compared to the other two solutions. These findings suggest that States 4 and 5 act as hubs for communication with other states, particularly States 2, 5, and 9, and States 1, 2, 4, and 9, respectively. This pattern is consistent with previous findings from idea-generation process studies using fMRI26. These results underscore the importance of dynamic large-scale network interactions in spatial insight problem-solving.

Comparison of psychological models for insight problem-solving

Our findings contribute to existing problem-solving models, particularly by highlighting the differences between analytical and insight-based processes. The longer RT and more diverse brain-state transitions observed in insight solutions may reflect the cognitive restructuring required, aligning with theories of sudden realization in insight problem-solving. In contrast, the more predictable and stable state transitions observed in analytical solutions support a linear, step-by-step approach characteristic of deliberate reasoning.

In this study, we decided to distinguish “quick solution” and “insight solution” even if both solutions may evoke “Aha!” experience in our preliminary experiment, because the processes of these solutions should possess different characteristics, as summarized by Jung-Beeman et al.4. We acknowledge that several studies22,23,25,27 have reported faster response times for insight solutions. Our finding that insight solutions were slower than analytical solutions can largely be attributed to the fundamental nature of the matchstick problems compared with the verbal insight task. The matchstick problem inherently demands visual restructuring and mental manipulation, which, even with a sudden “Aha!” experience can lead to longer overall solution times than rapid verbal recall. Our “quick solution” category (mean RT: ~ 9s) captures very rapid, intuitive solutions, which might align with some “Aha! experiences” in other contexts. In contrast, our “insight solutions” (mean RT: ~ 30s) represent a distinct process involving an impasse followed by restructuring, which is typically more time-consuming in this task domain. In addition, the hit rates showed the highest accuracy in the quick solutions than in the insight solution (see in the Result section). Our finding that insight solutions showed lower accuracy than analytical solutions also contrasts with some prior work28 and reflects the demanding nature of matchstick problems. True insight problems often present high initial failure rates and even a feeling of “Aha!” experience does not always guarantee a correct solution owing to the complexity of the required restructuring.

While our study provides valuable insights, it does not definitively identify which psychological model, such as the Wallas1 or Geneplore models2, best explains the insight problem-solving. However, the dynamic brain states revealed by the HMM, particularly during the extended processes leading to a solution, offer meaningful contributions to the understanding of cognitive flexibility. Rather than following a strictly sequential process, we observed distinct neural patterns depending on the problem-solving strategies employed. Specifically, the high variability, represented by high entropy in the insight solution, seems to indicate a transition from the “generate” phase to the “explore” phase based on pre-inventive forms, as proposed in the Geneplore model (Supplementary Fig. 4). The variability in brain states prior to insight solutions suggests a more flexible cognitive approach that may align with the principles of the Geneplore model.

Limitations of this study

The MA task, with its spatial and mathematical demands, provided a unique context for studying problem-solving, minimizing the influence of vocabulary or verbal memory, unlike previous studies. Our results suggest that the involvement of the DMN in insight solutions may be linked to internal processes that reflect the task’s realistic problem-solving demands. Future studies should aim to develop a more comprehensive problem-solving model by incorporating extended time frames and exploring additional processes beyond those captured in this study.

Additionally, we did not assess the generalizability of our findings to other types of insight problem-solving, such as verbal insight tasks (e.g., RAT). Identifying brain states that generalize across different tasks is crucial for understanding the dynamic brain processes underlying complex problem-solving. Despite this, we confirmed the generalizability of our HMM model on our specific dataset using leave-one-subject-out cross-validation (LOSO CV). This is particularly important given the limited sample size of the insight solution compared with the quick solutions in our experimental protocol. Future research should aim to modify insight problem solving tasks to better capture these rare events, further enhancing the generalizability of our findings.

This is the first study to investigate the temporal dynamics of brain states during insight problem-solving, such as rare events, using the MA task across three sessions for each participant. Based on participants’ reports of problem-solving strategies, we identified distinct spatial patterns of brain activity for quick, analytical, and insight solutions using the GLM. Additionally, we characterized dynamic brain states corresponding to different solving strategies, with the insight solution showing more flexible state transitions than the more stable state transitions in the quick and analytical solutions. Our findings suggest the possibility of “representation change,” which is crucial for overcoming an impasse or halting progress toward solutions.

Methods

Participants

Sixteen healthy participants (6 women, 10 men; mean age, 22.5 ± 2.3 years) were recruited. All participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision, no history of drug use affecting the central nervous system, and no neurological disease. The study was approved by the ATR Review Board Ethics Committee and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to the experiment. The participants received cash remuneration for their involvement in each session.

Experimental paradigm

The experiment comprised three scanning sessions within a two-week period, with 18–19 fMRI scanning runs for each participant. In each session, fMRI data were collected during a 10-min eyes-open resting-state run and four or five MA task runs using the Presentation Version 20.3 software (Neurobehavioral Systems Inc., CA, USA). We developed and implemented the MA task using Arabic numerals, in contrast to the Roman numerals used in previous studies7,29. In this task, participants were instructed to identify the correct arithmetic statement (the solution) by moving a single matchstick from one position to another, without adding or discarding sticks and without using the signs; “ ≠ ,” “ < ,” and “ > .” Based on a previous study, we prepared 44 equations consisting of four types of operations: type-A, type-B, type-C, and type-D6. A complete list of questions and answers is presented in Supplementary Table 1.

Type-A problems require moving a stick within the same numerical character. For example, in the equation “1 + 2 = 2,” participants must change the right-hand side “2” to “3,” yielding the solution “1 + 2 = 3.”

Type-B problems involve changing numerical characters, by moving a stick from one numeral to another, which has been shown to be more difficult in previous studies6,30. For instance, in “11–9 = 6,” participants must move a stick from the “9” on the left to the “6” on the right, producing the solution “11–3 = 8.”

Type-C problems require the alteration of a sign or operator. For example, in “3 + 8 = 6,” participants must move a stick from the “6” on the right-hand side to the leftmost position to form a minus sign (“–”), resulting in the solution “− 3 + 8 = 5.” Another example is “3–8 = 5,” where participants must interchange a horizontal stick between the equal sign (“ = ”) and the minus sign (“– “) to obtain “3 = 8–5.”

Type-D problems involve changing a two-digit number into a one-digit number and vice versa. For example, in the equation “11 + 2 = 9,” participants must change the two-digit number “11” to “7,” producing the solution “7 + 2 = 9.” Another example is “4–6 = 5,” where participants must change the one-digit number “4” to the two-digit number “11”, resulting in the solution “11–6 = 5.”

Each run consisted of 13 questions, with task difficulty determined by the proportion of solution types, ranging from 1 to 8 (Supplementary Table 2). Due to substantial individual differences in response times (RTs), it was not possible to predetermine the total scanning volume for a single run. Therefore, the maximum number of questions was set to 13, and the maximum duration was limited to 18 min. To maintain the participants’ motivation and concentration during the MA task with fMRI scanning, the first run started with a task difficulty of 1.

Subsequently, the task level was increased stepwise across runs in the same session. The experimental procedure was performed over three days. On the first day (Session 1), participants completed structural MRI scanning and fMRI acquisitions, including a T1-weighted structural image, a 10-min resting-state fMRI, and four MA-task runs with difficulty levels ranging from 2 to 5. On the second day (Session 2), participants underwent five runs of fMRI acquisitions, consisting of a 10-min resting-state fMRI and four to five MA-task runs with difficulty levels from 3 to 7. On the third day (Session 3), fMRI acquisitions included a 10-min resting state fMRI and four to five MA-task runs with difficulty levels ranging from 4 to 8. The proportion of solution types was adjusted based on task difficulty (Supplementary Table 2).

Prior to MRI scanning, the participants completed a practice run of the MA task with a difficulty level of 1 to familiarize themselves with the basic matchstick operations. Each trial consisted of five phases.

-

Fixation A crosshair appeared at the beginning of each trial for 15 s.

-

Question An MA equation was presented on the screen (e.g., “1 + 2 = 2”). Participants had three options: (i) provide a solution if they found one by pressing a button with their index finger; (ii) if they could not answer a solution within the maximum duration (240 s), they would proceed to the next trial, starting with the “Fixation” phase; or (iii) skip the question by pressing a button with their ring finger due to reduced motivation, proceeding directly to the “Fixation” phase for the next trial.

-

Response for the answer Participants were instructed to provide the solution to the equation (e.g., the correct solution for “1 + 2 = 2” is “1 + 2 = 3,” and the correct answer is “3”). Participants were required to ensure that the values on both sides of the equation were identical if the answer was correct.

Participants selected one answer from three options displayed on the screen: “2” (index finger), “3” (middle finger), or “other” (ring finger). The option “other” was included to prevent participants from deducing the correct answer based on the presence of only valid choices in this phase of this study.

For the “Response for solution” phase, participants were asked, “How did you solve the problem?” They chose from three options: (1) “quick solution,” which was found immediately or with minimal trial and error; (2) “analytical solution,” which involved solving the problem through multiple trials and errors, often by chance; and (3) “insight solution,” where participants initially paused then suddenly found a new approach that led to the solution. Our primary motivation for including “quick solutions” stems from recognizing that problem-solving behavior often involves a spectrum of cognitive processes, not limited to just analytical reasoning or a sudden “Aha!” moment. We define a “quick solution” as a problem solved almost instantaneously and intuitively, without conscious step-by-step deliberation (as in analytical solutions) or a period of impasse followed by restructuring (as in insight solutions). This category captures instances where subjects might rely on highly automatic or well-processed, akin to the rapid, intuitive judgements observed in experts (e.g., board game experts24).

For the “Response for difficulty” phase, participants rated the difficulty of the task by selecting one of two options: “easy” or “difficult.” This subjective difficulty rating was not included in the further analyses.

MRI data acquisition

Images were acquired using 3T MRI scanners (MAGNETOM Prisma; Siemens Medical Systems, Erlangen, Germany) with a 64-channel head coil at the Brain Activity Imaging Center of ATR. High-resolution T1-weighted structural images were acquired in Session 1 for normalization to a standard brain for echo-planar image (EPI) registration purposes (repetition time [TR] = 2400 ms, echo time [TE] = 2.22 ms, flip angle = 8°, inversion time [TI] = 1000 ms, matrix size = 256 × 256, field of view = 256 mm, slice thickness = 0.8 mm, isotropic-voxel). Functional images were acquired using an EPI sequence (TR = 1000 ms, TE = 30 ms, flip angle = 50°, matrix size = 100 × 100, field of view = 200 mm, slice thickness = 2.0 mm, no gap, 72 slices, interleaved scan sequences, multi-band acceleration factor = 6) oriented parallel to the anterior commissure-posterior commissure plane.

For the resting-state scans, 600 EPI brain volumes were acquired in the first run of each session (600 volumes × 3 sessions × 16 participants). For the MA task, 161,616 volumes were acquired. In total, 190,416 volumes were collected over the three-session experiment across all participants (see Supplementary Table 3 for more details).

Preprocessing of functional MRI data

We followed the preprocessing protocol described in a previous study31. The data were processed using SPM12 (Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging). The initial 10 volumes were discarded to allow T1 equilibration. The remaining data were corrected for slice timing and realigned to the mean image of the sequence to correct for head movements. Next, the structural image was coregistered with the mean functional image and segmented into three tissue types in the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space. The functional images were normalized and resampled to a 2 × 2 × 2 mm grid using the corresponding parameters. Finally, they were spatially smoothed using an isotropic Gaussian kernel with an 8 mm full-width at half-maximum.

General linear model

A first-level analysis was conducted on a participant-by-participant basis using a general linear model (GLM) in SPM12, as described previously 31. T-statistics were computed for each participant using boxcar regressors convolved with a canonical hemodynamic response function, excluding the time and dispersion derivatives. Preprocessed individual functional images were subjected to a high-pass filter with a cutoff period of 128 s to remove low-frequency drift. Additionally, six head movement parameters obtained from the realignment procedure were included as nuisance regressors. The fMRI data from each run were modeled with three regressors of interest (“quick,” “analytical,” and “insight”) corresponding to the task blocks in the run. For the “quick” solution regressor, onset times were aligned with the start of the “Question” phase, with durations matching the RT. For the “analytical” and “insight” solution regressors, onsets were set to 9 s before the button press during the “Question” phase, with fixed durations of 9 s for the analysis (Fig. 3a). For comparison, we also conducted an additional GLM analysis the entire Solution phase as a single block for all types (see in Supplementary Fig. 2).

To identify the brain areas activated for each solution type, contrast images were calculated for the following comparisons: (i) insight > analytical, (ii) insight < analytical, (iii) insight > quick, (iv) insight < quick, (v) analytical > quick, and (vi) quick > insight. One participant was excluded from the GLM analysis because of the lack of annotating of any “insight” solutions. The contrast images were used as input data for group-level analyses employing random-effects models and one-sample t-tests. The threshold for statistical significance was set at an uncorrected p value of less than 0.001, with a cluster-based family-wise error (FWE) correction applied at a p value of less than 0.05.

Hidden Markov model (HMM)

HMM is an analysis method that discretizes dynamic systems into a pre-defined number of states in a sequential manner. To represent discrete brain states in a data-driven manner, we applied the HMM using the HMM-MAR MATLAB toolbox (https://github.com/OHBA-analysis/HMM-MAR) to the temporal time course of whole-brain activity at rest and during tasks15,16. Brain state sequences were estimated from the activity of 14 brain networks derived from whole-brain fMRI data at each time point. This estimation was performed using the HMM with variational Bayesian inference and Gaussian distributions (mean activations), with the order of the MAR model set to zero.

The preparation of the time courses for the 14 networks involved the following steps: (i) computing the average signal of all voxels within each network mask32 (Supplementary Fig. 1); (ii) discarding the first 10 scans and demeaning the time courses; (iii) regressing out six head motion parameters, along with the average signals from gray matter, white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid, and applying a bandpass filter (transmission range, 0.01–0.1 Hz); and (iv) standardizing the data by dividing the standard deviation for each participant and each run. Subsequently, the data for each participant were temporally concatenated into a data matrix with dimensions of 14 × 190,416 (Supplementary Table 3). The number of states for the HMM was a free parameter that needed to be selected prior to further analysis. Therefore, the HMM estimated the brain state sequence at each time point from the matrix, exploring models with 8 to 11 brain states, using 500 training cycles and 15 repetitions. To select the most consistent model, we employed the Munkres (Hungarian) algorithm for linear assignment problems, as described in a previous study15, and determined that an HMM with 9 states was most suitable for our dataset. For generalizability, we performed a leave-one-subject-out (LOSO) cross-validation. This approach allowed us to access the consistency and robustness of our identified brain states and to perform model selection within each cross-validation fold. We quantitatively evaluated state consistency and selected the optimal model in each fold through the following steps:

Step 1 Reference model definition: We first defined a reference model which has already been trained using the entire dataset above. This model served as our benchmark for state characteristics.

Step 2 LOSO Training & Model Selection: In each iteration, we trained an HMM model on data excluding one subject (the test set). From these newly trained models, we selected the optimal model by identifying the model whose estimated states showed the lowest dissimilarity to the reference model (Step1). Dissimilarity was calculated using Kullback–Leibler (KL)-divergence from the mean and covariance of each state with the Gaussian distributions, minimized with the Hungarian algorithm.

Step 3 Label Matching & Evaluation: Finally, the held-out test data (excluded subject) was applied to the selected model from Step 2 to obtain its brain states. We then confirmed high matching from Step 1 and Step 3 based on the Random Index, further validating the state consistency.

We computed three key metrics for each solution: the cumulative time spent in a particular state (fractional occupancy, FO), the time duration each participant remained in a specific state (dwell time, DT), and the probability of transitioning between states (state transition probability, ST). From the HMM, the spatial patterns of each state were visualized as the mean activation across the 14 brain networks (Fig. 2). These fMRI signals were used to identify unique patterns of mean activity corresponding to each brain state. This output provided insights into the most expressed brain states during rest and the MA task across the three sessions. The dynamic aspects of brain states were derived from the state paths, allowing us to parameterize the dynamics across rest and MA tasks for the 9 s prior to answering, based on the mean RT for the quick solution. Specifically, we evaluated (i) FO and DT for each brain state (Fig. 2) and (ii) state transition matrices, which encode the likelihood of transitioning between states for each participant and run (Fig. 2).

To evaluate the dynamics of brain states between rest and the MA task based on solution types, we analyzed the dynamic metrics—FO and DT—for each brain state. To compare FO across the three solutions (quick, analytical, and insight) within each state, we employed one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Statistical significance was set at 0.05. When a significant main effect detected, Tukey–Kramer honestly significant difference (HSD) post-hoc test were performed to identify specific differences between solution pairs using functions ‘anova1.m’ and ‘multcompare.m’ in the Statistics Toolbox, MATLAB (* p < 0.05; ** p < 0.005). In addition, we compared FOs between the reference model and LOSO cross validation models in Supplementary Fig. 3. A threshold of 20% was set to identify the most common transitions. Finally, using the Network-Based Statistics (NBS) toolbox (version 1.2), we identified networks of STs that were significantly more prevalent during the solution types prior to answer onset compared to rest and, inversely, during rest compared to the solutions.

As post-hoc analyses, we further characterized the temporal patterns of long-term brain state dynamics during rest, as well as during “analytical” and “insight” solutions. First, we calculated the mean probability of FO for each state at each time point during the inter-stimulus interval, such as the “Fixation” phase (rest) and the entire solving period prior to the answer lasting longer than 30 s. We then identified the state with the highest probability (Fig. 5). Additionally, we quantified brain state variability, represented by entropy (\(Entropy=-{\sum }_{i=1}^{n}{p}_{i}\text{log}{p}_{i}\), where n and pi denote the number of states and the probability of i-th state, respectively), across three conditions: rest during the “Fixation” phase, insight solutions, and analytical solutions. This was done using the bootstrapping method across time and participants with 100 repetitions. Subsequently, we conducted a one-way ANOVA to statistically compare condition-dependent variability (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Data availability

Data for tasks are provided in the supplementary information file. Other data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Takeshi Ogawa, upon reasonable request.

References

Wallas, G. The Art of Thought (Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1926).

Finke, R. A., Ward, T. B. & Smith, S. M. Creative Cognition: Theory, Research, and Applications 239 (The MIT Press Creative Cognition, 1992).

Sowden, P. T., Pringle, A. & Gabora, L. The shifting sands of creative thinking: Connections to dual-process theory. Think. Reason. 21, 40–60 (2015).

Jung-Beeman, M. et al. Neural activity when people solve verbal problems with insight. PLoS Biol. 2, E97 (2004).

Tik, M. et al. Ultra-high-field fMRI insights on insight: Neural correlates of the Aha!-moment. Hum. Brain Mapp. 39, 3241–3252 (2018).

Aihara, T., Ogawa, T., Shimokawa, T. & Yamashita, O. Anodal transcranial direct current stimulation of the right anterior temporal lobe did not significantly affect verbal insight. PLoS ONE 12, e0184749 (2017).

Chi, R. P. & Snyder, A. W. Facilitate insight by non-invasive brain stimulation. PLoS ONE 6, e16655 (2011).

Chrysikou, E. G., Morrow, H. M., Flohrschutz, A. & Denney, L. Augmenting ideational fluency in a creativity task across multiple transcranial direct current stimulation montages. Sci Rep 11, 8874 (2021).

Green, A. E. et al. Thinking cap plus thinking zap: tDCS of frontopolar cortex improves creative analogical reasoning and facilitates conscious augmentation of state creativity in verb generation. Cereb Cortex 27, 2628–2639 (2017).

Lucchiari, C., Sala, P. M. & Vanutelli, M. E. Promoting creativity through transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS). A critical review. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 12, 167 (2018).

Luft, C. D. B., Zioga, I., Banissy, M. J. & Bhattacharya, J. Relaxing learned constraints through cathodal tDCS on the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Sci. Rep. 7, 2916 (2017).

Salvi, C., Beeman, M., Bikson, M., McKinley, R. & Grafman, J. TDCS to the right anterior temporal lobe facilitates insight problem-solving. Sci. Rep. 10, 946 (2020).

Koizumi, K., Ueda, K., Li, Z. & Nakao, M. Effects of transcranial direct current stimulation on brain networks related to creative thinking. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 14, 541052 (2020).

Baldassano, C. et al. Discovering event structure in continuous narrative perception and memory. Neuron 95, 709–721 (2017).

van der Meer, J. N., Breakspear, M., Chang, L. J., Sonkusare, S. & Cocchi, L. Movie viewing elicits rich and reliable brain state dynamics. Nat. Commun. 11, 5004 (2020).

Stevner, A. B. A. et al. Discovery of key whole-brain transitions and dynamics during human wakefulness and non-REM sleep. Nat. Commun. 10, 1035 (2019).

Da Mota, P. A. et al. The dynamics of the improvising brain: A study of musical creativity using jazz improvisation. In bioRxiv, p. 2020.01.29.924415 (2020)

Yu, Y., Oh, Y., Kounios, J. & Beeman, M. Dynamics of hidden brain states when people solve verbal puzzles. Neuroimage 255, 119202 (2022).

Cabral, J., Kringelbach, M. L. & Deco, G. Functional connectivity dynamically evolves on multiple time-scales over a static structural connectome: Models and mechanisms. Neuroimage 160, 84–96 (2017).

Vidaurre, D., Smith, S. M. & Woolrich, M. W. Brain network dynamics are hierarchically organized in time. PNAS 114, 12827–12832 (2017).

Vidaurre, D. et al. Spontaneous cortical activity transiently organises into frequency specific phase-coupling networks. Nat. Commun. 9, 2987 (2018).

Yu, Y., Oh, Y., Kounios, J. & Beeman, M. Electroencephalography spectral-power volatility predicts problem-solving outcomes. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 36, 901–915 (2024).

Yu, Y., Oh, Y., Kounios, J. & Beeman, M. Uncovering the interplay of oscillatory processes during creative problem solving: A dynamic modeling approach. Creat. Res. J. 35, 1–17 (2023).

Wan, X. et al. The neural basis of intuitive best next-move generation in board game experts. Science 331, 341–346 (2011).

Becker, M., Sommer, T. & Kühn, S. Verbal insight revisited: fMRI evidence for early processing in bilateral insulae for solutions with AHA! Experience shortly after trial onset. Hum. Brain Mapp. 41, 30–45 (2020).

Beaty, R. E., Benedek, M., Silvia, P. J. & Schacter, D. L. Creative cognition and brain network dynamics. Trends Cog. Sci. 20, 87–95 (2016).

Salvi, C., Bricolo, E., Kounios, J., Bowden, E. & Beeman, M. Insight solutions are correct more often than analytic solutions. Think. Reason. 22, 443 (2016).

Becker, M., Yu, Y. & Cabeza, R. The influence of insight on risky decision making and nucleus accumbens activation. Sci. Rep. 13, 1–14 (2023).

Knoblich, G., Ohlsson, S., Haider, H. & Rhenius, D. Constraint relaxation and chunk decomposition in insight problem solving. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 25, 1534–1555 (1999).

Ogawa, T., Aihara, T., Shimokawa, T. & Yamashita, O. Large-scale brain network associated with creative insight: Combined voxel-based morphometry and resting-state functional connectivity analyses. Sci. Rep. 8, 6477 (2018).

Ogawa, T., Shimobayashi, H., Hirayama, J.-I. & Kawanabe, M. Asymmetric directed functional connectivity within the frontoparietal motor network during motor imagery and execution. Neuroimage 247, 118794 (2022).

Shirer, W. R., Ryali, S., Rykhlevskaia, E., Menon, V. & Greicius, M. D. Decoding subject-driven cognitive states with whole-brain connectivity patterns. Cereb Cortex 22, 158–165 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We thank Hiroki Moriya for supporting the task design, Yoko Matsumoto, Mihoko Sato, and Arisa Katagiri for assisting with the MRI experiments, and Ryuta Tamano for contributing to the discussion of the results.

Funding

Takeshi Ogawa was supported by the JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Numbers JP 20K20400, JP21K12620, JP24K15692) and MIC/SCOPE (Grand Number #192107002).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T. O. contributed to the conception and design of the study. Material preparation was carried out by T. A. and T. O., while data collection and data analysis were performed by T. O. The manuscript draft was written by T. O., T. A., and O. Y. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ogawa, T., Aihara, T. & Yamashita, O. Neural correlates and dynamical brain states of creative insight in a spatial problem task. Sci Rep 15, 28216 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13684-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13684-y