Abstract

This study explores how artificial intelligence technologies can enhance the regulatory capacity for legal risks in internet healthcare based on a machine learning (ML) analytical framework and utilizes data from the health insurance portability and accountability act (HIPAA) database. The research methods include data collection and processing, construction and optimization of ML models, and the application of a risk assessment framework. Firstly, the data are sourced from the HIPAA database, encompassing various data types, such as medical records, patient personal information, and treatment costs. Secondly, to address missing values and noise in the data, preprocessing methods such as denoising, normalization, and feature extraction are employed to ensure data quality and model accuracy. Finally, in the selection of ML models, this study experiments with several common algorithms, including extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost), support vector machine (SVM), random forest (RF), and deep neural network (DNN). Each algorithm has its strengths and limitations depending on the specific legal risk assessment task. RF enhances classification performance by integrating multiple decision trees, while SVM achieves efficient classification by identifying the maximum margin hyperplane. DNN demonstrates strong capabilities in handling complex nonlinear relationships, and XGBoost further improves classification accuracy by optimizing decision tree models through gradient boosting. Model performance is evaluated using metrics such as accuracy, recall, precision, F1 score, and area under curve (AUC) value. The experimental results indicate that the DNN model performs excellently in terms of F1 score, accuracy, and recall, showcasing its efficiency and stability in legal risk assessment. The principal component analysis-random forest (PCA+RF) and RF models also exhibit stable performance, making them suitable for various application scenarios. In contrast, the SVM and K-Nearest Neighbor models perform relatively weaker, although they still retain some validity in certain contexts, their overall performance is inferior to deep learning and ensemble learning methods. This study not only provides effective ML tools for legal risk assessment in internet healthcare but also offers theoretical support and practical guidance for future research in this field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rapid advancement of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) is profoundly transforming the healthcare industry. These technological developments exhibit immense potential in enhancing diagnostic accuracy, optimizing treatment plans, and improving patient health outcomes, driving medical services toward greater intelligence, precision, and personalization1. Among these advancements, AI-powered internet of medical things (IoMT) devices are particularly noteworthy. These devices enable comprehensive monitoring and management of patient health by integrating sensor technology, real-time data analytics, and remote communication capabilities2. For instance, smart wearable devices, remote monitoring systems, and automated health management platforms have achieved significant success in areas such as chronic disease management and telemedicine, greatly improving the quality and efficiency of healthcare services3.

However, as the scope of technological applications expands, the collection, storage, sharing, and usage of medical data become increasingly complex, raising pressing concerns about data privacy breaches, ethical disputes, and insufficient regulation4. These issues pose unprecedented challenges to existing legal and technical frameworks, with the protection of medical data privacy and compliance emerging as critical priorities. In the United States, for example, the regulation of medical data privacy and security is primarily governed by the health insurance portability and accountability act (HIPAA). It aims to standardize the use and protection of patients’ sensitive information. Nevertheless, with the rapid proliferation of AI and ML technologies in healthcare, the limitations of traditional legal frameworks are becoming increasingly evident. This is particularly true in addressing emerging challenges such as real-time data learning, algorithmic updates, and cross-platform data interactions5. For instance, AI models might inadvertently expose patients’ private data during the training process, while IoMT devices face heightened cybersecurity risks during data transmission and cloud processing. Moreover, the “black box” nature of AI systems, characterized by their lack of algorithmic transparency, further complicates regulatory oversight6. This opacity not only undermines the trust of patients and healthcare institutions in AI-driven decisions but also hampers regulators’ ability to accurately assess compliance. Striking a balance between technological innovation and risk control has become a critical challenge for the healthcare industry and regulatory authorities alike.

Against this background, this study takes the HIPAA database as the research entry point to explore issues related to ML-driven medical supervision and legal risk assessment. Given the lack of a systematic ML integration framework in the field of legal risk identification in ML, this study adopts multiple types of models in algorithm selection (including ensemble learning, deep neural network (DNN), kernel methods, etc.). It also introduces principal component analysis (PCA) and model fusion strategies in the experimental design, thus proposing an ML assessment path suitable for high-dimensional heterogeneous medical data. Although the models used are mainstream algorithms, their combined application, performance analysis, and adaptability optimization in legal risk identification have targeted practical value.

Literature review

Many scholars have explored the applications of ML in the healthcare domain. Gilbert et al.7 discussed the use of AI and ML in healthcare and highlighted the regulatory challenges associated with adaptive algorithmic model updates. As the performance of ML models in healthcare improved over time, regulatory frameworks gradually shifted toward a dynamic approach. For instance, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) proposed quality management systems and algorithm change protocols. Similarly, the European Union introduced comparable drafts, although their details remained underdeveloped. These studies suggested that innovative approaches to healthcare must align with novel regulatory methods to simultaneously enhance medical services and ensure patient safety. Syed and Es8 noted that the widespread adoption of IoMT devices not only enhanced the quality of healthcare services but also introduced significant challenges related to cybersecurity and data privacy. AI-driven security frameworks, leveraging ML algorithms and anomaly detection techniques, monitored threats in real-time and responded swiftly, thereby improving the cybersecurity of such devices. However, ethical concerns and regulatory implications associated with these technologies required further investigation to balance technological innovation with the protection of patient privacy. Gerke et al.9 proposed that a shift from product evaluation to a system-level regulatory perspective was critical for ensuring the safety and efficacy of medical AI/ML devices. However, this shift posed substantial challenges for traditional regulatory bodies. They recommended that regulators adopt a system-level approach to assess the overall safety of AI healthcare products, rather than focusing solely on performance testing. This approach offered new insights into the personalized development of healthcare services and the innovation of legal regulatory frameworks. Shinde and Rajeswari10 explored the application of ML techniques in health risk prediction, demonstrating their potential in processing electronic health record datasets. ML methods effectively predicted disease risks and provided decision support for physicians. The advantage of this technology lies in its ability to learn from historical data and optimize healthcare resource allocation through automated analysis. However, they emphasized the need for further research on its applicability in real-world scenarios and the associated ethical concerns. Mavrogiorgou et al.11 conducted a comparative study on seven mainstream ML algorithms across various healthcare scenarios. These algorithms included Naïve Bayes, decision trees, and neural networks, among others, and were applied to the prediction of diseases such as stroke, diabetes, and cancer. The study revealed significant differences in algorithm performance across specific scenarios, highlighting the necessity of constructing a tailored algorithm selection framework based on data characteristics and medical requirements. This analysis provided theoretical support for improving the accuracy and reliability of medical AI models. Saranya and Pravin12 reviewed advancements in ML for disease risk prediction, covering a technical overview, algorithm selection, and future research directions. The study demonstrated that ML remarkably improved the accuracy of medical predictions but faced challenges such as data privacy, algorithm interpretability, and regulatory compliance. This review offered a reference for applying ML in legal risk assessment and optimizing regulatory frameworks.

To sum up, existing literature generally emphasizes the extensive application potential of AI and ML technologies in the medical field, covering multiple aspects such as diagnostic assistance, risk prediction, and resource optimization. However, these studies also reveal the legal, ethical, and regulatory challenges faced in the process of algorithm deployment. On this basis, this study further analyzes the applicability and risk control mechanisms of ML models under the HIPAA regulatory framework. Meanwhile, it attempts to provide empirical evidence and feasible suggestions for the technical supervision of legal risks in internet healthcare through paths such as classification label standardization, model output structure constraints, and the introduction of future interpretability mechanisms.

Experimental design

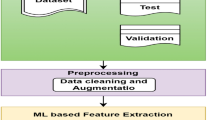

This study employs an ML-based analytical framework, leveraging data from the HIPAA database to explore how ML technologies can enhance the regulatory capacity for legal risk management in internet healthcare. Specific methods encompass data collection and processing, construction and optimization of ML models, and risk assessment based on evaluation frameworks. The steps are detailed below.

Data collection and processing

The primary data source for this study is the HIPAA database, which contains comprehensive information on medical data privacy protection, including patients’ medical records, insurance details, and related usage data. The data types in the HIPAA database encompass both textual data, such as medical records and personal information, and numerical data, such as treatment costs and medical course details. Structurally, the data includes both structured and unstructured formats, with the latter primarily involving medical texts and images. Due to issues with data quality, such as missing values or noise, essential data preprocessing must be performed prior to analysis to ensure the accuracy of model training and risk assessment results.

Data preprocessing involves several critical steps. First, to eliminate outliers and erroneous data, noise reduction is applied to identify and rectify inconsistencies in the data. Next, considering the potential dimensional inconsistency in numerical data, the z-score normalization method is utilized. Specifically, z-score normalization transforms data into a standard normal distribution with a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one, which can be written as Eq. (1):

\(X\) represents the raw data value; \(\mu\) is the mean of the feature, and \(\sigma\) refers to the standard deviation. Through this standardized method, numerical data can be compared and analyzed on the same scale, which improves the model’s training effect and accuracy.

Furthermore, for textual data, the term frequency-inverse document frequency (TF-IDF) method is used for feature extraction. TF-IDF is a statistical approach to measure the importance of terms within a collection of documents. By calculating the frequency of each term in a document and its distribution across the entire document set, the method evaluates the significance of terms effectively. This approach enables the extraction of meaningful features from large volumes of textual data, providing essential inputs for ML model training. Consequently, the data processing steps establish a more reliable and accurate foundation for subsequent ML model development.

Selection and construction of ML models

This study selects a variety of common ML algorithms for experimental analysis and constructs corresponding models to predict and evaluate legal risks in internet healthcare. The algorithms selected include random forest (RF), support vector machine (SVM), DNN, and extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost).

The RF algorithm. RF is an ensemble learning method based on decision tree construction, which improves classification performance by integrating the prediction results of multiple trees. RF uses bootstrap sampling to randomly select subsets from the data for training, and votes on the predicted results of each tree13. Firstly, data cleaning is performed, including denoising and missing value processing, to ensure the quality of the training data. Each tree is trained independently, and the characteristic of RF is to adopt random feature bagging for each tree, rather than using all features14. This process enhances the diversity of the model and reduces the risk of overfitting. The equation for information gain is as follows:

\(IG(T,A)\) denotes the gain of feature \(A\) on the dataset \(T\); \(H(T)\) represents the entropy of the dataset; \({T}_{v}\) is a subset divided by a value \(\text{v}\) of feature \(A\).

When all trees have completed training, RF integrates the predictions for each tree by voting (for classification tasks) or averaging (for regression tasks) to make a classification decision. The integrated voting is expressed in Eq. (3):

\({y}_{i}\) indicates the prediction for each decision tree, and \(\widehat{y}\) refers to the final prediction.

Compared to traditional single decision trees, RF introduces randomness during the training process, specifically by incorporating randomness when selecting split attributes. This enhances the model’s diversity and robustness. In RF, each decision tree is constructed independently, and the final prediction is determined by voting among the predictions of all decision trees15. If the model contains n decision trees, each sample will have n prediction results. RF selects the class with the highest number of votes as the final prediction result by aggregating the votes across all trees. The flowchart for generating the forest in the RF algorithm is presented in Fig. 1.

The process of decision-making in the RF algorithm is displayed in Fig. 2.

The SVM algorithm. SVM is a classification method based on the maximum margin hyperplane. It looks for a hyperplane in the high-dimensional space to separate different classes of samples, and the optimal hyperplane is the plane that maximizes the margin16.

Data preprocessing: SVM has high requirements for data standardization, and often uses the z-score standardization method to process numerical data. As a result, the data have a distribution with a mean value of 0 and a standard deviation of 117.

Finding the hyperplane: Given the training data \(\{({x}_{1},{y}_{1}),\dots ,({x}_{n},{y}_{n})\}\), the SVM finds the optimal hyperplane by solving an optimization problem that aims to maximize the boundary spacing while guaranteeing that all data points are correctly classified. The optimization objectives are:

\(w\) denotes the normal vector of the hyperplane, and the constraint is: \({y}_{i}(w\cdot {x}_{i}+b)\ge 1\).

For nonlinear separable data, SVM utilizes kernel tricks to map the data to a higher-dimensional space to solve nonlinear classification problems. Common kernel functions include linear kernels, Gaussian kernels, and others18. The Gaussian kernel function is shown in Eq. (5):

\(x\) and \({x}{\prime}\) refer to the input vectors; \(\upsigma\) represents the parameters of the Gaussian kernel.

The DNN algorithm. DNN is a multilayer perceptron (MLP) structure that enables complex pattern learning through multi-layer networks. DNN has powerful capabilities in handling large-scale data and complex nonlinear relationships, particularly suitable for the classification and regression of complex data such as images and speech19.

Data preprocessing: Similar to SVM, DNN requires high standardization of input data, so z-score standardization is usually performed first. For text data, TF-IDF or word embedding methods are employed.

The DNN architecture is revealed in Fig. 3.

The DNN consists of an input layer, multiple hidden layers, and an output layer. Each layer includes a number of neurons, each connected to all the neurons in the previous layer, and a weighted sum is performed. The output is nonlinearly transformed by activation functions such as ReLU, Sigmoid, etc.20. The neuronal calculation reads:

\({z}^{(l)}\) indicates a linear combination of the \(\text{l}\)-th layer; \({W}^{(l)}\) stands for the weight matrix; \({a}^{(l-1)}\) refers to the activation value of the previous layer; \({b}^{(l)}\) is the bias term; \(\upsigma\) represents the activation function. The cross-entropy loss function is commonly used to evaluate the predictive performance of a model, which is represented by Eq. (8):

\({y}_{i}\) refers to real labels; \({\widehat{y}}_{i}\) is predicted probability.

Selection and construction of XGBoost. XGBoost is an ensemble learning method based on gradient boosting, widely used for classification and regression tasks. It enhances the traditional gradient boosting algorithm by introducing a regularization term to control model complexity and prevent overfitting21.

Data preprocessing: Similar to other models, XGBoost requires data standardization and denoising prior to training.

Construction of tree models: XGBoost improves classification accuracy by incrementally building multiple decision trees. Each new tree is trained based on the residuals of the previous model, correcting the errors made in the prior iteration.

The loss function and regularization are expressed by Eq. (9):

\(l({y}_{i},{\widehat{y}}_{i})\) means the target loss; \(\Omega ({f}_{k})\) represents the regularization term.

Performance evaluation metrics

The evaluation metrics for the proposed model in this study include the F1-score, accuracy, precision, and recall. Accuracy measures the proportion of correctly predicted samples out of the total number of samples, and its calculation is defined as follows:

\(TP\) represents the number of positive samples correctly predicted as positive by the model, while \(TN\) denotes the number of negative samples correctly predicted as negative. Moreover, \(FP\) refers to the number of negative samples incorrectly predicted as positive; \(FN\) indicates the number of positive samples incorrectly predicted as negative. Precision measures the proportion of correctly classified positive samples out of the total number of samples predicted as positive by the classifier. The predictive ability of the model is directly proportional to its precision. The equation for precision reads:

The recall measures the ratio between the number of positive samples correctly classified by a classifier and the total number of positive samples. It mainly refers to the proportion of predicted positive text to actual emotional text. The calculation is given in Eq. (12):

Accuracy and recall constitute a pair of interdependent evaluation metrics, with high accuracy often accompanied by low recall, while high recall results in relatively low accuracy, presenting an opposing relationship between the two. The F1 score is the harmonic average of precision and recall, calculated as follows:

Results and discussion

Experimental configuration and data description

To improve the transparency of model construction and the reproducibility of results, this study systematically explains various ML models’ input features, output targets, training set size, and modeling process on the HIPAA dataset. The HIPAA dataset covers two types of information: structured and unstructured data. Structured data mainly includes numerical variables such as medical treatment costs, insurance types, and time-series information, which are uniformly processed through z-score standardization to ensure consistent data scales. Unstructured text data, such as electronic medical records and diagnostic descriptions, is processed using the TF-IDF method to extract keyword frequency features. These two data types are fused to form a unified high-dimensional input vector, with the final input dimension being 520.

In terms of setting output variables, the core task of this study is to identify potential legal risk types in Internet healthcare services. The model is constructed in a multi-class single-label manner, that is, each sample corresponds to only one risk label. There are six risk categories in total: data leakage risk, compliance violation risk, privacy infringement risk, cross-border data transmission risk, misdiagnosis and abuse risk, and contract dispute risk. All models (including DNN) adopt a softmax output structure, generating a six-dimensional probability vector each time. This represents the predicted probability of each type of risk, and the one with the highest probability is taken as the final prediction result. Therefore, this study adopts a single-model multi-output classification structure rather than multiple independent binary classifiers.

Regarding data partitioning, the original dataset contains 18,000 valid samples. These datasets are divided into a training set (70%, 12,600 samples), a validation set (15%, 2700 samples), and a test set (15%, 2700 samples) using stratified sampling according to category proportions. This ensures that the distribution of various risks is consistent across different subsets.

For model training configuration, the DNN adopts a three-layer hidden layer structure with 256, 128, and 64 neurons in sequence. The activation function uses ReLU, the output layer adopts the softmax function, and a Dropout layer (with a dropout rate of 0.3) is set to prevent overfitting. The optimizer is Adam with a learning rate of 0.001, and the loss function is cross-entropy. The maximum number of training epochs is 50, and an early stopping mechanism on the validation set is used to prevent over-training. The RF model employs 200 trees with a maximum depth of 15, improving the model’s generalization ability through Bootstrap sampling and feature bagging, and the final output is determined by majority voting. The SVM model uses a radial basis function kernel with parameters set to C = 1.0 and gamma = ‘scale’. Considering the computational pressure caused by high-dimensional features, PCA reduces the input dimension to 50 before training. The XGBoost model is set with 100 boosting rounds, a maximum tree depth of 6, regularization parameters λ = 1 and α = 0.5, and the evaluation metric is multi-class logarithmic loss. The K-nearest neighbor (KNN) model sets the number of neighbors to 5 and uses Euclidean distance for classification. The Principal Component Analysis-Random Forest (PCA+RF) model first applies PCA to reduce the dimension to the first 50 principal components (with cumulative explained variance exceeding 90%). They are then input into a random forest with 150 trees for training.

In terms of validation and parameter tuning, all models are evaluated for performance on the test set. Parameters are optimized through fivefold cross-validation on the training set, and grid search is used to find the optimal combination. Three independent repeated experiments are conducted, and the average value is taken to reduce fluctuations caused by random initialization and improve the stability and reliability of the results.

Analysis of model performance

This study compares the models’ accuracy, recall, F1 score, and Area under the curve (AUC) value to assess the performance of different ML models in legal risk assessment for internet healthcare. Additionally, it analyzes the training and testing time to evaluate the models’ effectiveness and efficiency. The six ML models include PCA+RF, SVM, RF, DNN, KNN, and XGBoost. Each model’s accuracy, recall, and F1 scores are suggested in Fig. 4.

According to Fig. 4, DNN performs the best, with an accuracy of 95.4%, a recall of 93.1%, and an F1 score of 94.2%, demonstrating its high efficiency and stability in risk assessment. PCA+RF also performs well, and its accuracy, recall, and F1 scores are 94.1%, 91.2%, and 92.6%, indicating an improvement in model performance through the integration of dimensionality reduction techniques. RF ranks third with an accuracy of 92.3%, a recall of 89.5%, and an F1 score of 90.8%, showing a balanced performance. XGBoost also demonstrates stable performance, demonstrating an F1 score of 92.3%, a recall of 91.0%, and an accuracy of 93.7%. In contrast, SVM and KNN exhibit relatively weaker performance across all metrics. SVM achieves an accuracy of 88.7%, recall of 85.2%, and an F1 score of 86.8%, whereas KNN shows even poorer performance, and its accuracy, recall, and F1 scores reach 87.2%, 84.0%, and 85.5%. These results suggest that DNN has a notable advantage in this domain. However, other models also demonstrate certain effectiveness, making them suitable for selection based on different needs and data characteristics.

Different models’ training time, testing time, and AUC values are denoted in Fig. 5.

In terms of AUC, DNN performs the best with a value of 0.975, illustrating strong classification ability. The second-best is PCA+RF, with an AUC value of 0.960, reflecting high accuracy. Other models, such as RF, XGBoost, SVM, and KNN, have lower AUC values, indicating slightly weaker classification performance. Regarding training time, DNN takes the longest, with a time of 48.3 s, while KNN has the shortest training time at only 10.5 s. The training times for other models range from 10.5 s to 19.7 s, showing relatively high training efficiency. Considering the testing time, DNN also has a longer testing time at 6.1 s, while KNN has the shortest testing time at just 1.9 s. Overall, DNN excels in AUC value but requires more time for training and testing, while other models like RF, PCA+RF, and XGBoost achieve a better balance between performance and time efficiency.

Impact of model parameters on performance

This section investigates the impact of adjusting key parameters in the ML models, exploring how different parameter settings influence model performance and optimizing parameters to improve the model’s effectiveness in legal risk assessment for internet healthcare. The RF model’s parameters include 50 trees, 100 trees, and 200 trees, while the DNN model’s layers are set to 2, 3, and 4. The results of the impact of model parameters on performance are plotted in Fig. 6.

Significant impacts on model performance can be observed with different settings by adjusting the key parameters of the RF and DNN models. For the RF model, as the number of decision trees increases from 50 to 200, the accuracy improves from 89.60% to 94.10%, recall increases from 87.20% to 91.30%, and F1 score rises from 88.30% to 92.50%. It indicates that more decision trees markedly enhance the model’s classification performance. In the DNN model, performance further improves as the number of layers rises from 2 to 4. Its F1 score, accuracy, and recall increase from 92.20% to 95.10%, 93.50% to 96.20%, and 91.00% to 94.50%, respectively, demonstrating that adding more layers optimizes the model’s learning ability and evaluation effectiveness. Overall, parameter optimization substantially enhances the model’s performance in legal risk assessment for internet healthcare.

Risk identification and classification result

This study identifies and classifies legal risks in Internet healthcare by using a DNN model to predict on the HIPAA database. Different risk categories are divided according to the prediction results, and the proportion of each category and the predicted risk identification rate are analyzed. The accuracy and risk identification rate presented in the figure are derived from the output results of a single DNN multi-classification model, rather than multiple independent binary classifiers. The model selects the category with the highest probability as the prediction label according to the softmax output, corresponding to six types of legal risks. The detailed classification results and their proportional analysis are depicted in Fig. 7.

Figure 7 shows that the data breach risk has the highest proportion, accounting for 25.4%. The risk identification rate is 91.2%, indicating that the DNN model performs well in identifying data breaches. The next most significant risk is compliance violation, with a proportion of 18.3% and an identification rate of 89.6%. Privacy invasion risk ranks third, with a proportion of 14.7%, and the highest identification rate of 93.0%. Other risks, such as cross-border data transfer, misdiagnosis and abuse, and contract dispute risks, show relatively balanced proportions and identification rates, at 12.8%, 15.1%, and 13.7%, respectively.

The model’s predictions for each risk category are shown in Fig. 8.

From the analysis of Fig. 8, it can be found that in each risk category, privacy invasion risk has the highest precision (93.5%) and recall (93.0%), with an F1 score of 93.2%, demonstrating strong identification ability. Data breach risk and misdiagnosis and abuse risks also perform well, with precision and recall of 92.1% and 91.2%, and 91.3% and 90.2%, respectively. Among them, cross-border data transfer risk has a relatively lower precision (88.2%), indicating that the identification of this risk category still requires further optimization. Overall, the DNN model can accurately predict various risk types in Internet healthcare, particularly excelling in the identification of data breaches, privacy invasions, and compliance violation risks.

Discussion

This study constructs a legal risk assessment model for internet healthcare based on ML techniques, systematically exploring the processes of data processing, model selection, and optimization. At the same time, it analyzes the performance and applicable scenarios of different algorithms based on experimental results. The following discussion covers the methodological effectiveness, comparison of model performance, practical significance, and future research directions.

The effectiveness and innovation of methodology

The proposed method is based on the HIPAA database, integrates ML and data mining technologies, and introduces a complete regulatory framework for legal risks in internet healthcare. Compared with traditional methods that rely on expert experience or simple rule settings, the ML method adopted in this study shows stronger flexibility and adaptability. In data preprocessing, combined with the characteristics of structured and unstructured data, efficient data integration is achieved through z-score standardization and TF-IDF feature extraction technology, providing a reliable data foundation for subsequent model training. This accurate data preprocessing not only improves the prediction effect of the model but also reduces risks caused by data quality problems. This study does not stop at the direct application of general models. However, it constructs an integrated framework based on multi-model comparison, PCA dimensionality reduction optimization, and high-dimensional medical data structure, combined with the characteristics of legal risks in internet healthcare. Especially in the data preprocessing stage, feature fusion is performed for the heterogeneity of text and numerical data. At the model level, models such as DNN and XGBoost are used to handle high-complexity risk structures, and a multi-model integration comparison system is designed. This multi-model comparison and integration strategy follows established practices in ML research and can provide useful reference for similar studies in related fields.

Analysis and comparison of model performance

The experimental results indicate that DNN outperforms other algorithms across multiple performance metrics (such as accuracy, recall, and F1 score), particularly excelling in handling complex nonlinear relationships and high-dimensional data. However, the DNN model also presents significant computational cost issues, with training times far exceeding those of other models. This highlights the need to balance high accuracy with computational resource constraints, especially in resource-limited practical environments.

In contrast, the PCA-RF model strikes a more favorable balance between performance and operational efficiency. By applying PCA to reduce the dimensionality of the data, the PCA-RF model significantly improves the efficiency of the RF algorithm. The reduction in dimensionality helps to streamline the computational process, enhancing operational speed without sacrificing accuracy or F1 score. This makes the PCA-RF model an ideal solution for tasks that require the processing of large volumes of data within a short time frame. For example, real-time monitoring of healthcare legal risks is paramount. In scenarios where quick decision-making is necessary, particularly in high-stakes environments like healthcare, the PCA-RF model emerges as a practical and reliable choice. The XGBoost model shows its advantages in handling medium-sized data and tasks with strong regularity. However, its performance is slightly inferior to that of DNN, especially in tasks requiring high-complexity pattern recognition. Therefore, XGBoost is more suitable for scenarios where risk characteristics are relatively clear, and not suitable for tasks that completely rely on complex pattern recognition.

Practical significance and regulatory enlightenment

The results of this study have significant practical implications in the field of legal risk regulation for internet healthcare. First, by constructing and optimizing ML models, accurate prediction and assessment of risks such as medical data privacy breaches and legal disputes can be achieved, thereby improving regulatory efficiency. Compared to traditional passive, reactive regulatory models, the model proposed in this study is more proactive and forward-looking, enabling regulatory bodies to devise corresponding risk prevention and control strategies before issues arise.

Second, the proposed model is highly scalable and can be applied to various internet healthcare scenarios. For example, in areas such as online medical consultations, remote diagnosis, and electronic health record management, the model can effectively monitor potential risks and provide scientific evidence for the formulation of related legal policies. Furthermore, this model can be extended to other data-sensitive fields, such as fintech and online education, thus enhancing its social value.

Finally, from an implementation perspective, regulatory bodies and healthcare institutions can use the proposed method to construct real-time monitoring systems for dynamic analysis of patient data access, transmission, and storage. Upon detecting potential risks, the system can automatically trigger warnings and generate processing recommendations, significantly reducing the likelihood of risk occurrence.

Limitations and future research directions

Although this study has made certain research advancements, it also has limitations. Although DNN performs well in this study, its “black-box nature” limits the interpretability of results. In legally and regulatory sensitive fields, model transparency is crucial. Future research can introduce interpretable ML technologies such as SHapley Additive exPlanations and Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations to visually analyze the contribution of key model features, enhancing the credibility and compliance of model output. In addition, the combination of symbolic logic and ML can be explored to support the automatic embedding and visual explanation of legal logic rules, thereby promoting the in-depth integration of “technology and regulations”.

Conclusion

This study, based on an ML analytical framework, explores methods to enhance legal risk regulation in the field of Internet healthcare and has achieved a series of significant results. The main conclusions are as follows:

-

(1)

The importance of data preprocessing.

By leveraging the diverse data from the HIPAA database, this study applies z-score standardization and TF-IDF methods to preprocess numerical and textual data effectively. This preprocessing step remarkably improves data quality, laying a solid foundation for subsequent model training and evaluation.

-

(2)

The effectiveness of ML models.

The study systematically compares the performance of various ML models, including RF, SVM, DNN, and XGBoost. Experimental results demonstrate that DNN achieves the highest accuracy (95.4%), recall (93.1%), and F1 score (94.2%) among all models, showcasing its advantage in handling complex nonlinear problems.

-

(3)

Performance evaluation and comprehensive analysis.

Using metrics such as precision, recall, F1 score, and AUC, this study comprehensively evaluates the practical performance of each model in legal risk assessment for internet healthcare. The analysis reveals distinct characteristics of each model. Overall, when identifying legal risks in internet healthcare, the DNN model can accurately predict various risk types, especially excelling in the identification of data leakage, privacy infringement, and compliance violation risks.

-

(4)

Suggestions for enhancing legal risk regulation capabilities.

The findings indicate that adopting ML techniques can effectively enhance legal risk regulation capabilities in the internet healthcare sector. In particular, high-performance models like DNN and XGBoost can assist regulatory agencies in achieving more precise risk prediction and assessment. Moreover, data preprocessing and feature extraction techniques, such as TF-IDF and dimensionality reduction, play a crucial role in improving model efficiency and accuracy.

-

(5)

Research significance and prospect.

This study presents a comprehensive, systematic, and practical technical solution for legal risk management in internet healthcare, which improves the accuracy of risk assessments and offers valuable references for data-driven regulatory frameworks. By exploring these dynamic environments, future studies could further refine the models to be more adaptive to new, unforeseen challenges in the regulatory space. Additionally, this study paves the way for exploring ML’s potential in automating legal compliance, which can reduce the administrative burden on healthcare providers and regulatory bodies. This ensures a more efficient and scalable solution to legal risk management.

In conclusion, this study validates the application value of ML techniques in the legal risk regulation of internet healthcare. Moreover, it contributes to practical policy recommendations that are relevant for stakeholders in this domain. By offering a clear foundation for the future exploration and refinement of ML-based risk management systems, it serves as a critical stepping stone for advancing research in this domain, driving innovation, and ensuring the sustainable, ethical, and legally compliant use of ML technologies in healthcare.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Nadella, G. S., Satish, S., Meduri, K. & Meduri, S. S. A systematic literature review of advancements, challenges and future directions of AI and ML in healthcare [Online]. Available: https://www.ijsdcs.com/index.php/IJMLSD/article/view/519/214 [Accessed 3 5]. (2023).

Rana, M. & Bhushan, M. Machine learning and deep learning approach for medical image analysis: Diagnosis to detection. Multimed. Tools Appl. 82, 26731–26769. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-022-14305-w (2023).

Muehlematter, U. J., Bluethgen, C. & Vokinger, K. N. FDA-cleared artificial intelligence and machine learning-based medical devices and their 510(k) predicate networks. Lancet Digit. Health 5, e618–e626. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2589-7500(23)00126-7 (2023).

Rasool, R. U., Ahmad, H. F., Rafique, W., Qayyum, A. & Qadir, J. Security and privacy of internet of medical things: A contemporary review in the age of surveillance, botnets, and adversarial ML. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 201, 33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnca.2022.103332 (2022).

Cui, S., Tseng, H.-H., Pakela, J., Ten Haken, R. K. & El Naqa, I. Introduction to machine and deep learning for medical physicists. Med. Phys. 47, e127–e147. https://doi.org/10.1002/mp.14140 (2020).

Venigandla, K. Integrating RPA with AI and ML for enhanced diagnostic accuracy in healthcare. Power Syst. Technol. 46, 33–42. https://doi.org/10.52783/pst.251 (2022).

Gilbert, S. et al. Algorithm change protocols in the regulation of adaptive machine learning-based medical devices. J. Med. Internet Res. 23, e30545. https://doi.org/10.2196/30545 (2021).

Syed, F. M. & Es, F. 2024. AI-powered security for internet of medical things (IoMT) devices [Online]. Available: https://redcrevistas.com/index.php/Revista [Accessed 1 15].

Gerke, S., Babic, B., Evgeniou, T. & Cohen, I. G. The need for a system view to regulate artificial intelligence/machine learning-based software as medical device. NPJ Digit. Med. 3, 53. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-020-0262-2 (2020).

Shinde, S. A. & Rajeswari, P. R. Intelligent health risk prediction systems using machine learning: A review. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 7, 1019–1023. https://doi.org/10.14419/ijet.v7i3.12654 (2018).

Mavrogiorgou, A. et al. A catalogue of machine learning algorithms for healthcare risk predictions. Sensors 22, 8615. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22228615 (2022).

Saranya, G. & Pravin, A. A comprehensive study on disease risk predictions in machine learning. Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. 10, 9. https://doi.org/10.11591/ijece.v10i4.pp4217-4225 (2020).

Uddin, M. S., Chi, G., Al Janabi, M. A. M. & Habib, T. Leveraging random forest in micro-enterprises credit risk modelling for accuracy and interpretability. Int. J. Financ. Econ. 27, 3713–3729. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijfe.2346 (2022).

Zhu, W., Zhang, T., Wu, Y., Li, S. & Li, Z. Research on optimization of an enterprise financial risk early warning method based on the DS-RF model. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 81, 102140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2022.102140 (2022).

Cohen, I. G., Gerke, S. & Kramer, D. B. Ethical and legal implications of remote monitoring of medical devices. Milbank Q 98, 1257–1289. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12481 (2020).

Akinnuwesi, B. A., Macaulay, B. O. & Aribisala, B. S. Breast cancer risk assessment and early diagnosis using principal component analysis and support vector machine techniques. Inf. Med. Unlocked 21, 100459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imu.2020.100459 (2020).

En-Naaoui, A., Kaicer, M. & Aguezzoul, A. A novel decision support system for proactive risk management in healthcare based on fuzzy inference, neural network and support vector machine. Int. J. Med. Inf. 186, 105442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2024.105442 (2024).

Wu, J. H. et al. Risk assessment of hypertension in steel workers based on LVQ and Fisher-SVM deep excavation. IEEE Access 7, 23109–23119. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2899625 (2019).

Andreeva, O., Ding, W., Leveille, S. G., Cai, Y. & Chen, P. Fall risk assessment through a synergistic multi-source DNN learning model. Artif. Intell. Med. 127, 102280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.artmed.2022.102280 (2022).

Duan, J. Financial system modeling using deep neural networks (DNNs) for effective risk assessment and prediction. J. Frankl. Inst. 356, 4716–4731. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfranklin.2019.01.046 (2019).

Abhadiomhen, S. E., Nzeakor, E. O. & Oyibo, K. Health risk assessment using machine learning: systematic review. Electronics 13, 4405. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics13224405 (2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.W.; methodology, S.L.; software, H.L.; validation, S.F.; formal analysis, Z.W.; investigation, S.L.; resources, Z.W., S.L.; data curation, H.L.; writing—original draft preparation, H.L., S.F., L.S., Z.W.; writing—review and editing, Z.W., S.L.; visualization, L.S.; supervision, H.L.; project administration, Z.W. All authors have read and agreed to the submitted version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, S., Liu, H., Fan, S. et al. Machine learning enables legal risk assessment in internet healthcare using HIPAA data. Sci Rep 15, 28477 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13720-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13720-x