Abstract

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) has a global occurrence of 0.59 to 3.69 per one lakh people. Palbociclib (Palbo), an inhibitor of CDK4 (cyclin dependent kinase) and CDK6, is used for treating cancer. Palbo showed a limited therapeutic effect in brains of transgenic mice after oral administration. Further, studies on P-glycoprotein (P-gp) and breast cancer resistant protein (BCRP) knock-out mice showed that P-gp and BCRP (efflux transporters) restrict Palbo’s permeability across the blood-brain barrier (BBB). Hence, the clinical usefulness of Palbo for treating GBM is limited. Palbociclib-loaded nanoparticles of albumin (Nps-Bsa-Palbo) and palbociclib-loaded nanoparticles of albumin conjugated with Polysorbate 80 (Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80) were formulated and optimized using Design Expert® 11.0.0. The Nps were prepared by desolvation with suitable size (195 nm and 221 nm) and zeta potential (13.4 mV and 10.6 mV). Nps-Bsa-Palbo and Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 exhibited greater inhibition against the SH-SY5Y cell viability in comparison with free Palbo. Studies on healthy male rats confirmed that Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 substantially enhanced Palbo distribution over free Palbo in the cerebellum, frontal cortex and posterior brain regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), the most common CNS tumour, has a global occurrence of 0.59 to 3.69 per one lakh people1. Even though there has been substantial advancements in chemotherapy, radiotherapy and surgical intervention, the median survival time, after diagnosis, is in between 12 and 15 months2,3. Further, about 3 to 5% of GBM patients manage to survive over a period of 3 years or longer4,5. In clinical trials, anti-GBM drugs failed to enhance GBM patients’ prognosis as they cannot easily cross the BBB6,7. The BBB functions as a tough membrane barrier that separates the blood stream from the brain. It’s selectivity limits the entry of variety of molecules into the CNS based on their charge, lipophilicity and molecular weight8. Therefore, the treatment of GBM by conventional delivery of anticancer drugs, surgical resection and radiation has been remained as a challenge9,10,11. Many studies have explored the possibilities of using various strategies to transport drugs into the brain12. Palbo, an inhibitor of CDK4 and CDK613, which regulate the progression of cell cycle, is used for treating cancer. It was the first CDK4/6 inhibitor approved by US-FDA and EMA in 2015. CDK4/6 pathways are hyperactive in several kinds of cancer cells and it has been observed in GBM that CDK4/6 or cyclin D are amplified13,14. The effectiveness of Palbo to treat cancer have been studied by many clinical trials15,16,17. Further, the usefulness of Palbo to treat brain tumour have been studied by few clinical trials18,19. In a study, de Gooijer et al. reported that Palbo penetration is restricted into the brain by P-gp and BCRP20. In another study by Martinez-Chavez et al. reported that P-gp restricts ribociclib exposure into the brain21. This clearly indicates that the clinical usefulness of these drugs to treat brain tumour are limited by the BBB. Design of Experiments (DoE) has emerged as an efficient method to optimize pharmaceutical formulations. The DoE can be used to identify a target response profile to generate and optimize the required response with superior safety, efficacy, and quality in healthcare. Factorial experiments are one of the most common methods to optimize processes and to identify the most dominant factor of the product and what level of these factors results in the desired product. In such context, designing and optimizing Bsa-based Nps of Palbo having a small size by factorial design is remarkable. In this paper, we describe the development of Palbo-loaded albumin Nps (Nps-Bsa-Palbo) to deliver Palbo into the brain for effective treatment of GBM. Further, coating of Nps with hydrophilic substances like Polysorbate 80 (Ps-80) increased the brain concentration of Palbo22,23.

Experimental

Materials

Palbo was generously provided as a gift by Hetero Drug Limited, India. Bsa was procured from Roche, USA. Polysorbate 80 (Tween 80), D (+) –glucose, dimethyl sulfoxide and glipizide were bought from Sigma-Aldrich Chemicals Private Limited, USA. The cell line SH-SY5Y was bought from the NCCS, Pune, India. The cell culture plates were obtained from Grenier Bio-One, Germany. All solvents and chemicals used for this research were of analytical grade.

Experimental design optimization by using DoE

The experimental independent variables, factors and factor levels were determined in two stages. To optimize the zeta potential, polydispersity index (PDI), and particle size: the following independent variables were selected: (i) concentration of albumin (mg) (X1), (ii) concentration of glutaraldehyde (%) (X2) and (iii) time of crosslinking (hours) (X3) (Supplementary Table 1). In the first stage of DoE, a full factorial (23) screening design was applied following the theory of Pareto principle (80/20 rule) by using Stat-Ease Inc.‘s Design Expert® 11.0.0 version statistical software (Minneapolis, MN, USA) to generate 8 experiments (Supplementary Table 2a) for each formulation variable by considering two different levels (the lowest and the highest values) (Supplementary Table 1). Next a study of the variables, screened at their optimum levels, was carried out using a central composite design (CCD) to generate 13 experiments (Supplementary Table 2b) for each formulation variable by considering five different levels (Supplementary Table 1).

Optimization of the Np formulations using CCD

In the experiments, a CCD matrix generated by Stat-Ease Inc.‘s Design Expert® 11.0.0 version was employed to examine the impact of two factors: albumin concentration (X1) and glutaraldehyde concentration (X2) on the zeta potential, the PDI and the particle size. The selected variables were examined at five various concentrations and were coded as -ɑ, -1, 0, 1, and +ɑ. Both orthogonality and rotatability were fulfilled in the design by calculating the value for alpha (-1.682). The CCD constituting 5 replicates at the centre points, 4 batches on axial points, and 4 batches on factorial points, was performed to estimate pure error sum of squares. The 13 batches of Np formulations are enlisted in Supplementary Table 2b. Using this design, the top model was selected from the linear model, the two-factor model with interaction, and finally the quadratic model by utilizing the Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). The optimized Np formulations were further used for in vitro evaluation to determine physico-chemical properties (morphological analysis of the surface, size of the particle, zeta potential, cytotoxicity, and release kinetics) and in vivo studies to determine the feasibility and ensure that they met specifications before use.

Formulation of Nps-Bsa-Palbo

The Nps-Bsa-Palbo were developed by desolvation with minor modifications24. In brief, albumin (130 mg) was dissolved in (10 mM) sodium chloride (8 mL) and stirred using a magnetic stirrer at 500 rpm. Palbo was dissolved in acetone and it was filled in a 3 mL Becton Dickinson syringe and added into the Bsa solution at an approximate flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. Acetone (desolvating agent) was gradually added until the mixture became turbid. To cross link the resulting Nps, 200 µL of glutaraldehyde (4% v/v) was added and the mixture was stirred for 4 h. Finally, 100 mg of glucose was added and stirred for 30 min. The Nps were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 30 min to remove the unloaded Palbo and lyophilized. For coating, 1%v/v Ps-80 was added (based on the total volume of suspension) to the Nps suspension after adding the cross-linker.

Characterization of Nps-Bsa-Palbo

The Np preparations (Nps-Bsa-Palbo and Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80) were characterized for the yield, drug loading, surface charge and morphology, mean size, drug release and release kinetics. The percentage yield was estimated by calculating the weight% of the final dried product in relation to the combined weight of substances used in the preparation. The average charge and size of Nps-Bsa-Palbo were assessed using the Litesizer 500 particle size analyser (Anton Paar, USA). The morphology of Nps-Bsa-Palbo was studied by a SEM (Joel, Japan). For drug loading determination, Palbo was fully extracted from 25 mg of Nps-Bsa-Palbo and the Palbo concentration was assessed using UV spectrophotometry at 267 nm.

In vitro Palbo release and Palbo release kinetics

Release of Palbo from the Nps was studied in in vitro using dialysis and the medium was PBS (pH 7.4) containing 0.2% (w/v) sodium lauryl sulphate. Nps equivalent to 1 mg of Palbo were loaded into a dialysis tube and dispersed in 1 ml of buffer before sealing at both ends. The dialysis bag was placed in 100 ml of buffer and stirred at 100 rpm at 37 °C. At regular intervals of time, 5 ml of dissolution medium was removed and an equal volume was replaced with fresh buffer to maintain sink conditions. The Palbo concentration was determined using UV spectrophotometry at 267 nm. The obtained data were fit to zero order, first order, Higuchi, Hixson-Crowell and Korsmeyer-Peppas to determine the most suitable fit.

In vitro cytotoxicity

MTT colorimetric assay was used for assessing the cytotoxicity of free Palbo, Bsa-Palbo and Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 on SH-SY5Y cells25. Briefly, DMEM containing 10% FBS was used to culture the SH-SY5Y cells and the cells were placed in 96 well plates. The cells density was 0.1 × 105 cells per well in 0.1 mL media and incubated under 95% oxygen and 5% carbon dioxide for 24 h at 37 °C. Once the cells reached a halfconfluent monolayer, they were washed by using PBS (pH 7.4), followed by adding the serum free medium into the wells, and thereafter incubated for 1 h. The serum free medium was also finally removed. While the control cells received the serum free medium, the test wells received different concentrations of free Palbo, Nps-Bsa-Palbo and Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 (0.05–100 µM) and the plates were incubated for 24 h. The cells were two times, after incubation, washed with PBS, followed by addition of fresh medium into the cells. MTT solution (10µL of 1 mg/mL) was added in each of the wells for evaluating cell viability and incubated for 4 h. The supernatants were removed, and 100µL of DMSO was utilized per well to solubilize the formazan complex, followed by spectroscopic measurement of absorbance at 540 nm. The percentage of viable cells of the test groups relative to the control groups is shown in the data.

In vivo animal study

Healthy Sprague-Dawley male rats (age: 8–12 weeks) were used for the study. In this study, the animal experiments were carried out after getting approval from Institutional Animal Ethics Committee, College of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Dayananda Sagar University, Bengaluru, India (DSU/Ph.D./IAEC/20/2018-19). The experiments were performed in accordance with the CCSEA, India guidelines. The rats were housed on a 12-hour light/12-hour dark cycle in a well-ventilated animal house. The temperature and humidity were 22 ± 3 °C and 50 ± 15% respectively. The rats were given unlimited access to water and a standard laboratory food. Rats were acclimatized a week before conducting the studies.

Pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution studies

For this, 81 healthy rats were randomly divided into three groups in which three rats were examined for nine sampling time points. A dose of 5 mg per kg body weight (Palbo, Nps-Bsa-Palbo and Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80) was injected intravenously in each of the three groups of 27 rats. Blood samples were obtained from the retro-orbital plexus and pre-labelled tubes containing anticoagulant (2% w/v K2EDTA solution) were used to collect blood samples. Isoflurane anaesthesia was employed during the blood collection and the intervals were 0.08, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 24 h. The blood was centrifuged for 10 min (1000 rpm) at 4 °C and the plasma samples were maintained at -85 °C until analysis. To study tissue distribution, the rats were euthanized in a humane manner using carbon dioxide technique. The organs, such as kidneys, lungs, liver, posterior brain region, cerebellum, and the frontal cortex, were expunged at various time intervals, followed by rinsing with normal saline, homogenization in PBS (pH 7.4) with 1:4 ratio and stored at -85 °C until analysis26,27.

Tandem mass spectrometry was utilised with liquid chromatography to quantify the Palbo concentrations in the tissue and plasma samples and all results were expressed as mean. The AUC (exposure) ratios of tissues to plasma were determined using tissue concentrations (AUC Kp ratio). The AUCs ratio attained from the profile of concentration-time in the corresponding matrix in relation to plasma was used to calculate the AUC Kp ratio for the frontal cortex, posterior brain region, cerebellum, liver, lungs, and kidney. The concentration at different time points was used to determine the pharmacokinetic parameters through a noncompartmental approach using Phoenix WinNonlin 8.3 software (Certara L.P., USA). Parameters, such as peak concentration (Cmax), terminal elimination half-life (t1/2), and the area under the plasma concentration-time curve up to the last quantifiable time point (AUC0–t) were calculated using mixed log-linear methods. The pharmacokinetic parameters (e.g., systemic clearance) were estimated as Dose/AUCinf and Vss as\(\:\text{C}\text{L}\times\:\text{M}\text{R}\text{T}\), where Vss = Volume of distribution, CL = Systemic plasma clearance, and MRT = Mean residence time. All data were expressed as means and graphs were prepared using Microsoft Excel 2013.

LC-MS/MS analysis

The Palbo concentration in plasma and the tissue samples were analysed by using an Acquity Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography (UPLC) system (Waters Corp., Milford, MA, USA). The analytes were eluted from the Acquity BEH C18 (Milford, Massachusetts, USA) 50 mm × 2.1 mm internal diameter column – with a mobile phase in a gradient state. The column was comprised of formic acid (0.1%) with ammonium formate (5 mM) in formic acid (0.1%) and water in acetonitrile at a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min. The column’s temperature was mainatined at 40 °C. 800 µL of weak wash solvent (acetonitrile and water, 1:9 (v/v)) and 600 µL of strong wash solvent (acetonitrile and water, 9:1 (v/v)) were used to inject 5 µL of the test sample. The analytes on an API-4000 MS (Applied Biosystems/MDS SCIEX, Toronto, Canada) were detected with Turbon Ion spray by using multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) with electrospray ionization (ESI). The parameters of mass spectrometer are described in Supplementary Tables 3 and 4. The calibration curves were made and determined employing weighted (1/x2) linear regression by plotting ratios of (peak area) analyte (Palbo) and nominal concentrations versus internal standard of analytes. The samples were diluted serially with a dynamic range of 1.03 to 1026.00 ng/mL for generating the calibration curves for Palbo. In plasma and tissues, the correlation coefficient (r2 was greater than 0.99. Separate calibration curves were made for blank rat plasma and blank tissues, and samples were prepared and analyzed using the appropriate matrix with a 4-fold dilution for tissue homogenate.

Statistical analysis

The findings are presented as means and standard deviations. Students’ ttest or oneway ANOVA was employed with Fisher’s test for assessing the statistical differences. A p value less than 0.05 was considered as significance.

Results

Screening and optimization of Nps by using DOE

In order to assess the significance of the studied variables, a 23-factorial design was constructed for screening. Supplementary Table 5 shows the combination of variables and the responses obtained after performing the experiments. The evaluated responses were: particle size and PDI. The results demonstrated that the particle size of the Np formulations ranged between 127.2 nm and 447.5 nm (Supplementary Table 5). Moreover, the minimum to maximum desired values for the responses are shown in Supplementary Table 6. The influence of time for cross-linking (X3), glutaraldehyde concentration (X2), and albumin concentration (X1) on the size of the particle and PDI of Np formulations is graphically illustrated as desirability charts (Supplementary Fig. 1a and 1b). As shown in Supplementary Fig. 1b, among the three selected variables, concentrations of albumin (X1) and glutaraldehyde (X2) showed a major influence on the responses. The figure shows that desirability of 0.92 can be obtained by combining the two variables. The selected variables were further used for the optimization of the Np formulations using CCD. Desirability ramp intended for the optimized Nps displaying the impact of process parameters (albumin concentration, glutaraldehyde concentration, and the cross-linking time) on the size of particle and PDI. (a) Desirability ramp intended for the optimized Nps formulations demonstrating the effect of process variables (concentrations of albumin and glutaraldehyde) on polydispersity index (PDI) and particle size. (b) RSM plots indicating the effect of the interaction among the process variables on zeta potential (c), polydispersity index (PDI), and particle size.

Optimization of Np formulations using CCD

Preparation of thirteen Np formulations in total were executed using CCD for optimizing two variables: the albumin concentration (X1) and the gluteraldehyde concentration (X2) at five levels. Analysis of all the batches were carried out for determining the zeta potential, PDI, and the size of the particle (Supplementary Table 7). It was found that batch 6 had the highest particle size (690.3 nm) and PDI (0.48%) when prepared using the highest albumin concentration and a comparatively lower concentration of glutaraldehyde (6%).

A quadratic (second-order) polynomial model, linear model, and a response surface three-dimensional plot, built with the software Design Expert®, were used to evaluate the impact of different factors on each of the responses. In order to find the variability in percentages in the various obtained responses, a significant effect had been determined, as well as p < 0.05 was deemed significant. ANOVA was employed for every response in order to determine the model’s significance and best fit, as depicted in Supplementary Table 8. The estimated values of both the albumin concentration (X1) and the glutaraldehyde concentration (X2) as determined by the coefficient were discovered as positive, implying that a rise in albumin as well as glutaraldehyde concentrations leads to an increased particle size. The quadratic (second-order) model was discovered to be significant statistically having a (p value = 0.0286) along with a lack of fit (F = 59.6193; p > 0.05) which was insignificant for the size of particle (Supplementary Table 8). Supplementary Fig. 1c depicts the three-dimensional response surface plot, which can also be used to analyse the impact of the main variables as well as the interactive variables on the particle size response. X1 denoted a p-value of 0.0068, whereas X2 denoted a p-value of 0.1079. In this case, X1 was a significant model term. Besides, the quadratic term for the concentration of glutaraldehyde (X22) was significant (p = 0.0412). Thus, positive and significant large values for X1 and X22 indicate that these two factors have a prime influence on the particle size (Y1), which is also congruent with Supplementary Fig. 1c. The rest of the factors were regarded as insignificant because their values of p were greater than 0.05.

Similarly, in the numerical model that describes the relation between the variables (X1, X2) and the response variable (Y2), the estimated values of both the albumin concentration (X1) and the glutaraldehyde concentration (X2) as determined by the coefficient were discovered as positive, implying that a rise in albumin as well as glutaraldehyde concentrations leads to an increased PDI. The quadratic model was found to be statistically significant (p = 0.0323) with an insignificant lack of fit (F = 2.23328; p > 0.05) for PDI (Supplementary Table 8). Supplementary Fig. 1c depicts the three-dimensional response surface plot, which can also be used to analyse the impact of the main variables as well as the interactive variables on the PDI response. X1 was found to have a value of (p = 0.0152), whereas X2 was found to have a value of (p = 0.2751). In this case, X1 was a significant model term. A decrease in the resultant factor was associated with an increase in zeta potential because the coefficient estimated value of albumin (X1) concentratration was negative. An increase in the resultant factor was associated with an increase in zeta potential because the concentration of gluteraldehyde (X2) was positive. The quadratic (second-order) model was statistically significant having a p value = 0.0066 along with a lack of fit (F = 30.6197; p > 0.05) which was insignificant for the zeta potential (Supplementary Table 8). Supplementary Fig. 1c depicts the three-dimensional response surface plot, which can also be used to analyse the impact of the main variables as well as the interactive variables on the zeta potential response. X1 denoted a p-value of 0.0343, whereas X2 denoted a p-value of 0.1024, indicating X1 to be a substantial model term. Besides, the quadratic term for the concentration of glutaraldehyde (X22) was significant (p = 0.0009). The results show that the concentration of albumin (X1) and the quadratic term for glutaraldehyde (X22) influence the zeta potential (Y3). Other factors were not significant.

Validation of optimized formulations

Furthermore, the experimental and theoretical means of the additional triplicate experiments are compared in preparation for the desired range of Np formulations to confirm the reliability and suitability of optimized conditions (Table 1). The variables and responses of the optimized formulations report that the particle size of the experimental combination was found to be 167.57 nm under modified settings and it matched with the theoretical value of 138.69 nm. Similarly, the zeta potential (16.2 mV) and PDI (0.25) of the experimental combination were well-matched with theoretical values (0.21 and 17.7 mV).

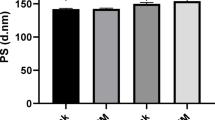

Nps-Bsa-Palbo

The Nps-Bsa-Palbo were prepared by desolvation. While the yield was 70.6 ± 5.3%w/w and 73.2 ± 4.6%w/w (Table 2) for Nps-Bsa-Palbo and Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 respectively, the drug loading was 8.5 ± 1.3%w/w and 5.5 ± 0.9%w/w (Table 2) for Nps-Bsa-Palbo and Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 respectively. The SEM pictures show that the particles are nearly spherical and uniform sized (Fig. 1A and B). While the particle size was 195 nm and 221 nm for Bsa-Nps and Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 (Fig. 2A and B) respectively, the zeta potential (ZP) was 13.4 mV and 10.6 mV (Fig. 3A and B) respectively. The polydispersity index was 0.23 and 0.25 for Bsa-Palbo-Np sand Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 respectively. Palbo exhibited sustained release from the Nps for 24 h with release percentages of 93.90 ± 2.43% and 90.93 ± 0.53% (Fig. 4) for Nps-Bsa-Palbo and Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 respectively. The n value of Nps-Bsa-Palbo and Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 for the Korsmeyer-Peppas model was 0.37 and 0.33 for Nps-Bsa-Palbo and Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 respectively and which is less than 0.45, indicating Fickian mechanism (Table 3).

In vitro cytotoxicity

The in vitro cytotoxicity of Palbo, Nps-Bsa-Palbo and Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 was examined on SH-SY5Y cells with various concentrations (0.05 to100 µM) and the results are given in Fig. 5. The Nps demonstrated a dose dependent inhibitory effect on SH-SY5Y cells. The IC50 value of Palbo, Nps-Bsa-Palbo and Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 was 0.86 µM, 0.60 µM and 0.60 µM respectively. This results indicate that the Nps significantly enhanced the cytotoxic effect of Palbo.

In vivo studies

Pharmacokinetic studies

The mean pharmacokinetic factors of Palbo, Nps-Bsa-Palbo and Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 were calculated using a noncompartmental approach (Table 4). The clearance rate was 21.8 ml/min/kg, 38.6 ml/min/kg and 22.8 ml/min/kg for Palbo, Nps-Bsa-Palbo and Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 respectively. The AUC was 1921 h×ng/mL, 3871 h×ng/mL and 3691 h×ng/mL for Palbo, Nps-Bsa-Palbo and Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 respectively. The t1/2 (half-life) was 2.1 h, 5.3 h and 5.5 h for Palbo, Nps-Bsa-Palbo and Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 respectively. The MRT (mean residence time) was 2.5 h, 6.3 h and 6.4 h for Palbo, Nps-Bsa-Palbo and Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 respectively. The Vss (volume of distribution) was 3.3 L/kg, 8.1 L/kg and 8.9 L/kg for Palbo, Nps-Bsa-Palbo and Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 respectively. It is clear from the pharmacokinetic studies and that Nps as well as Nps coated with PS-80 significantly altered the pharmacokinetic parameters of Palbo when compared with free Palbo. It is clear from Fig. 6 that Nps are able to sustain the Palbo concentration in the blood.

Tissue distribution study in rats

The tissue-plasma ratios (Kp) and the mean data of AUC0-t and Cmax of Palbo, Nps-Bsa-Palbo and Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 are given in Table 5 (Figs. 7 and 8). The Palbo concentration level was found to be higher in all the tissues after iv administration of Nps-Bsa-Palbo and Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 in comparison with free Palbo. Nps-Bsa-Palbo and Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 increased the brain AUC0-t of Palbo by 3.38-fold and 5.88-fold in the cerebellum; 4.25-fold and 9.05-fold in the brain posterior region; 5.26fold and 16.89-fold in the frontal cortex, in comparison with free Palbo. The Nps-Bsa-Palbo increased the AUC0-t of Palbo by 2.95-fold, 3.58-fold and 4.25-fold in the lungs, liver and kidney respectively. At the same time, Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 increased the Palbo concentration by 4.03-fold, 5.03-fold and 9.05-fold in the lungs, liver and kidney respectively. Nps-Bsa-Palbo increased the brain concentration of Palbo by 9.55-fold, 7.03-fold and 3.93-fold in the frontal cortex, brain’s posterior region and cerebellum respectively in comparison with free Palbo. Whereas, Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 increased Palbo’s brain concentration by 32.04-fold, 29-fold and 8.59-fold in the frontal cortex, brain’s posterior region and cerebellum respectively in comparison with free Palbo. This shows that Ps-80 coating substantially enhanced the brain concentration of Palbo as well as altered the brain distribution pattern.

Discussion

Optimization

The optimization results indicated that for the 13 formulations, the influence of different factors resulted in particle size ranging from 85.4 to 690.3 nm, indicating that particles smaller than 100 nm were also obtained, but in many batches the size ranged between 150 nm and 700 nm. This finding is somewhat similar to a previous finding where prednisolone acetate encapsulated chitosan Nps showed a size range of 161.5 nm to 604.9 nm28. Also, it was noted that the batch prepared with the highest concentration (batch 6) of albumin and a relatively lower concentration of glutaraldehyde exhibited the highest particle size and PDI (Supplementary Table 7). The PDI varied between 0.13 and 0.48. PDI value < 0.5 suggests uniform-sized particles in the dispersed phase. A monodisperse system is likely to aggregate less than a polydisperse system. Besides, the range of the zeta potential of all 13 formulations (2.3 to 17.7 mV) suggested the stability of the Nps. These values indicate that just one fragment of amino groups is deactivated in the production of NPs29. Iftikhar28 reported similar findings and the PDI of all the optimized Np formulations ranged between 0.25 and 0.82 with positive zeta potential (5.72 and 21 mV). Moreover, ANOVA findings for the reduced quadratic equation indicated that the zeta potential, PDI, and particle size were affected by the independent factors, namely, the concentration of albumin (X1) and quadratic term for glutaraldehyde (X22) (Supplementary Table 8).

Palbo-Bsa-Nps

Both natural and synthetic polymers have been extensively studied for preparing Nps. But usage of water insoluble polymers usually need organic solvents, high speed stirring and heat which sometimes affect drugs’ efficacy and stability. Generally, mild and simple methodology is required when water soluble polymers are used to make Nps. Further, these methods avoids high speed stirring and harmful organic solvents. Albumin Nps can be formulated using techniques including desolvation, nano spray drying, thermal gelation, nab-technology, self-assembly and emulsification. In this study, Nps-Bsa-Palbo were formulated using the desolvation method. While the yield was 70.6 ± 5.3%w/w and 73.2 ± 4.6%w/w (Table 2) for Nps-Bsa-Palbo and Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 respectively, the drug loading was 8.5 ± 1.3%w/w and 5.5 ± 0.9%w/w (Table 2) for Nps-Bsa-Palbo and Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 respectively. The method produced Nps with good drug loading, and the lyophilized form was a free flowing powder. Many surfactants such as polysorbates, poloxamers and poloxamines have been studied to find out their effectiveness for transporting drugs into the brain. It was found that polysorbate-80 was more effective for brain drug delivery and this was further supported by many studies30,31,32. Hence in the present study, we also used polysorbate 80 to transport Palbo into the brain. Drug loading should be high for any nano-based carrier to minimize the amount of nano-carrier required per millilitre of solvent during administration. If drug loading is less, large quantity of carrier is required to administer the required dose in the target site. This may result in systemic toxicity after iv administration and cause more problem to degrade, metabolize and excrete the carrier materials to the patients. This limits the clinical translation of nanoparticles33. The SEM pictures show that the particles are nearly spherical and uniform sized (Fig. 1A and B).

Particle size and zeta potential

Particle size, hydrophobicity and charge significantly influence the biological fate of Nps following administration, as they play a crucial role in Nps’s interaction with plasma membrane. Nps size play a major role to deliver anticancer drugs in tumour site. In the present study, while the particle size was 195 nm Nps-Bsa-Palbo, it was 221 nm for Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 (Fig. 2A and B). Nps can get easy access inside the body and transported to various sites through blood circulation. Moreover, size of particle play a significant role to deliver anticancer drugs into the cancer cells. In a study Yuan et al. reported that the pore size of blood capillaries of LS 174T tumour (a human colon adrenocarcinoma) is about 400 nm34. This shows that if the particle size is below 400 nm then the nanoparticles can be taken up by the cancer cells by passive targeting because of EPR effect. Hence, it can be hypothesized that the formulated Nps will be readily internalized by glioma cells after traversing the BBB via the EPR effect. Ps-80 coting slightly increased the size of particles. Many studies reported that Ps-80 coating increased the particle size22,23. Further, this confirms the coating of particles with Ps-80. The PDI showed a narrow distribution pattern and it was 0.23 and 0.25 for Nps-Bsa-Palbo and Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 respectively. PDI gives information about Nps’ distribution pattern as well as resemblance between Nps’ sizes. Particles with unequal size affect the pharmacokinetic pattern which further influence the Nps’ therapeutic efficacy35. Zeta potential (ZP) indicates charge on the surface of Nps and an increase in the value indicates more charge on the particles’ surface. Nps with high negative or positive charge result in high repulsive forces and the high repulsion in between the Nps with similar charge avoid particles’ aggregation, therefore helps easy redispersion and improve product stability36. A ZP value of 20 mV with either positive or negative charge is desirable, in case of combined steric and electrostatic stabilization Nps37. The Nps-Bsa-Palbo had a ZP of 13.4 mV, while the Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 had a value of 10.6 mV (Fig. 3A and B) and the obtained values are sufficient to produce a stable Nps suspension. Ps-80 coating slightly reduced the charge and this could be explained by the fact that the coating masked the charge on the surface38. We also observed similar findings in our earlier studies39.

In vitro Palbo release

The Palbo release was 93.90 ± 2.43%w/w and 90.93 ± 0.53%w/w for Nps-Bsa-Palbo and Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 respectively (Fig. 4). After 1 h, the Palbo release was 6.75 ± 0.75%w/w for Nps-Bsa-Palbo and 6.14 ± 0.04%w/w for Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 and this was owing to the burst release. It is well known that the drug bound with the Nps’ surface dissolve when they are exposed to dissolution medium which results in burst effect. The initial rapid Palbo release was linked to the Palbo molecules trapped in the surface layer of the particles, which dissolve when contact with the buffer40. We observed similar findings in our earlier studies41. The remaining Palbo was released in a slow and sustained way and which is greatly desired in anti-cancer drug delivery. The prolonged release of Palbo was attributed to the Palbo incorporated into the inside core of Nps. A lower anticancer drug level in the blood is always desirable as it decrease the side effects and the drug level should be higher at the target organ (cancer cells) to increase the anticancer efficacy42. It can be noted that after iv injection, the Nps minimize Palbo release in the blood while increasing Palbo concentration in the cancer cells/tissues (target organ), which inturn increase Palbo’s efficacy. The Palbo release was diffusion controlled from the Nps and the Palbo release mechanism was Fickian as the n value is less than 0.45 for Korsmeyer-Peppas model (Table 3)43.

In vitro cytotoxicity

Albumin is a nontoxic, non-immunogenic, biocompatible, biodegradable and water soluble polymer. The products obtained from degradation of albumin are not harmful to the body44. The in vitro cytotoxicity of Palbo, Nps-Bsa-Palbo and Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 was examined on SH-SY5Y cells with various concentrations (0.05 to100 µM) and the results are given in Fig. 5. The Nps demonstrated a dose dependent inhibitory effect on SH-SY5Y cells. The IC50 value of Palbo, Nps-Bsa-Palbo and Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 was 0.86 µM, 0.60 µM and 0.60 µM respectively. The Np bound drug is readily taken up by the tumour cells owing to EPR effect. This could be the reason that Nps containing Palbo showed significantly enhanced cytotoxic effect.

In vivo studies

Particles with a size less than 7 μm are commonly, after iv injection, absorbed by the reticuloendothelial system primarily by the liver Kupffer cells45,46. We also observed the similar pattern in our studies. A higher Palbo concentration was found in the liver with Nps when compared with free Palbo. The maximum mean Palbo concentration (Cmax) achieved in the liver when administered as free Palbo and Palbo bound with the Nps was 2441.4 ng/g and 19543.3 ng/g respectively. Similar trend was found in the case of lungs and kidneys. In lungs the Palbo concentration achieved after iv administration of free Palbo and Palbo bound with Nps was 12720.7 ng/g and 40,983 ng/g respectively, whereas it was 485.2 ng/g and 3413.7 ng/g respectively in kidneys. Similar kind of results were reported in other studies for other drugs47,48. The Cmax was increased in the case of liver, lungs and kidneys when the Nps were coated with Ps-80 and it was 19931.8 ng/g, 69296.3 ng/g and 14075.6 ng/g respectively. Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 increased the Palbo concentration by 4-fold, 5-fold and 9-fold in the lungs, liver and kidney respectively (Table 4). The higher concentration of Palbo achieved in these organs, when it was bound with Nps, could be useful to deliver drugs into these organs to treat metastatic state of glioma as in metastasis the cancer cells reach other organs including liver, lungs and kidneys. The higher Palbo concentration achieved in the kidneys when bound with Nps was in accordance with previous studies for other drugs49.

The maximum mean Palbo concentration (Cmax) achieved in the brain when administered as free Palbo, Nps-Bsa-Palbo and Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 was varied in different parts of the brain tissues. In frontal cortex, it was 129.2 ng/g, 1234.5 ng/g and 4139.8 ng/g for as free Palbo, Nps-Bsa-Palbo and Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 respectively, whereas it was 161.8 ng/g, 1137.9 ng/g and 4691.9 ng/g for as free Palbo, Nps-Bsa-Palbo and Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 respectively in posterior region of brain. In cerebellum, it was 120.4 ng/g, 473.1 ng/g and 1034.5 ng/g for as free Palbo, Nps-Bsa-Palbo and Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 respectively. Nps-Bsa-Palbo increased the brain concentration of Palbo by 10-fold, 7-fold and 4-fold in the frontal cortex, brain’s posterior region and cerebellum respectively in comparison with free Palbo. Whereas, Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 increased the Palbo’s brain concentration by 32-fold, 29-fold and 9-fold in the frontal cortex, brain’s posterior region and cerebellum respectively in comparison with free Palbo (Fig. 7).

The mean brain AUC0 − t for free Palbo, Nps-Bsa-Palbo and Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80, after iv administration, was also varied in different parts of the brain tissues. In frontal cortex, it was 383.8 h × ng/g, 2019.5 h × ng/g and 6484.2 h × ng/g for as free Palbo, Nps-Bsa-Palbo and Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 respectively, whereas it was 757.5 h × ng/g, 3220 h × ng/g and 6857.8 h × ng/g for as free Palbo, Nps-Bsa-Palbo and Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 respectively in posterior region of brain. In cerebellum, it was 402.5 h × ng/g, 1359.8 h × ng/g and 2365 h × ng/g for as free Palbo, Nps-Bsa-Palbo and Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 respectively. Nps-Bsa-Palbo increased the brain AUC0 − t of Palbo by 5-fold, 4-fold and 3-fold in the frontal cortex, brain’s posterior region and cerebellum respectively in comparison with free Palbo. Whereas, Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 increased the brain AUC0 − t of Palbo by 17-fold, 9-fold and 6-fold in the frontal cortex, brain’s posterior region and cerebellum respectively in comparison with free Palbo (Table 5; Fig. 8).

The mean tissue-plasma ratio for free Palbo, Nps-Bsa-Palbo and Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80, after iv administration, was also varied in different parts of the brain tissues. In frontal cortex, it was 0.2, 0.5 and 1.8 for as free Palbo, Nps-Bsa-Palbo and Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 respectively, whereas it was 0.4, 0.9 and 1–9 for as free Palbo, Nps-Bsa-Palbo and Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 respectively in posterior region of brain. In cerebellum, it was 0.2, 0.4 and 0.7 for as free Palbo, Nps-Bsa-Palbo and Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 respectively. Nps-Bsa-Palbo increased the tissue-plasma ratio of Palbo by 2.5-fold, 2.25-fold and 2-fold in the frontal cortex, brain’s posterior region and cerebellum respectively in comparison with free Palbo. Whereas, Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 increased the tissue-plasma ratio of Palbo by 9-fold, 4.75-fold and 3.5-fold in the frontal cortex, brain’s posterior region and cerebellum respectively in comparison with free Palbo. The biodistribution study results showed that Nps coated with Ps-80 significantly increased the brain concentration of Palbo. This is important as Palbo can not easily penetrate across the BBB. Further, the Nps are expected to be easily internalized by the tumour cells. Hence, it is obvious that the Palbo loaded Nps minimize the side effects on normal brain cells.

Many studies explored the possibility of delivering drugs into the brain by nanobased formulation50,51,52,53,54,55. Troster et al. observed that poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) Nps labelled with14C coated with surfactants which includes Ps-80, after iv injection, increased the amount of Nps reached into the rat brain30 Later studies conducted on in vitro bovine microvessel endothelial cell cultures confirmed PS-80 coating improved the brain uptake of PMMA Nps31. Thereafter, drugs which cannot penetrate across the BBB, dalargin56loperamide57tubocuraine58and doxorubicin59were delivered by Ps-80 coated poly(butyl cyanoacrylate) Nps into the brain. Drug loaded Nps which were not further coated with Ps-80 failed to exhibit therapeutic efficacy which indicates Ps-80’s crucial role in brain targeting60. Further, the specific role of Ps-80 coating in brain targeting was supported by many studies48. Our study also further confirms these findings.

Various mechanism have been hypothesized in brain targeting using Nps coated with Ps-80. Nps get accumulated, after injection, in the brain capillaries which enhances concentration gradient followed by Nps penetration across the endothelial cell layer. Lipids present in the endothelial cell membrane get solubilized which improves membrane fluidization followed by drug penetration. Ps-80 opens the tight junctions which allows entry for the free drug and drug loaded Nps. The Nps can be transported into the brain by receptor mediated endocytosis. Apolipoproteins like E and/or B get adsorbed on Ps-80 coated Nps, when the Nps are introduced into the blood. After apolipoprotein adsorption, the Nps function similarly to low density lipoproteins (LDL) and engaging with the LDL receptors of the BBB and internalized by the process called receptor-mediated endocytosis61. Numerous studies provided support for the receptor mediated hypothesis. In a study apolipoproteins like B-100, A-1 and E3 were attached with loperamide incorporated Nps and the apolipoproteins functionalized Nps elicited antinociceptive activities after in injection in mice. This shows the involvement of various interactions in brain targeting by Nps62. Based on the earlier hypothesis, it is believed that the Nps are transported via receptor mediated endocytosis in the present study.

Conclusion

Delivery of anticancer drugs by nanomedicines such as Nps and liposomes have numerous advantages including targeting drugs into the cancerous cells. Further, Nps can improve drugs’ efficacy, tolerability, circulation time and protect the loaded drug from degradation. Albumin Nps have been extensively as a carrier for a variety of drugs63,64. The US-FDA approved, in 2005, the first human serum albumin based Nps containing paclitaxel (Abraxane® to treat metastatic breast cancer after combination therapy failure65,66. Abraxane® enhanced paclitaxel’s solubility with numerous advantages over the conventional formulations. This shows the potential usefulness of albumin Nps to target anticancer drugs. In the present study, we successfully prepared Nps-Bsa-Palbo and surface functionalized with PS-80. In comparison with free Palbo, Nps-Bsa-Palbo and Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 exhibited greater inhibition against the SH-SY5Ycell viability. Studies on healthy male rats confirmed that Nps-Bsa-Palbo-Ps-80 substantially enhanced palbociclib distribution over free Palbo and Nps-Bsa-Palbo in different parts of the brain, namely, frontal cortex (17fold and 3fold), posterior brain region (9fold and 2fold) and cerebellum (6fold and 2fold). The high Palbo concentration achieved in the brain, in our studies, can be considered as a significant improvement for treating GBM. The findings presented here are derived from the Palbo concentrations attained in the brain and other vital organs. Therefore, additional studies are necessary to determine its potential as a drug delivery system.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ostrom, Q. T. et al. CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and other central nervous system tumorsdiagnosed in the united States in 2013–2017. Neuro Oncol. 22 (12 Suppl 2), iv1–iv96 (2020).

Stupp, R. et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant Temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl. J. Med. 352, 987–996 (2005).

Wen, P. Y. & Kesari, S. Malignant gliomas in adults. N Engl. J. Med. 359, 492–507 (2008).

Ohgaki, H. Epidemiology of brain tumors. Methods Mol. Biol. 472, 323–342 (2009).

Martinez, R. et al. Frequent hypermethylation of the DNA repair gene MGMT in long-term survivors of glioblastoma multiforme. J. Neurooncol. 83, 91–93 (2007).

Wu, W. et al. Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM): an overview of current therapies and mechanisms of resistance. Pharmacol. Res. 171, 105780 (2021).

Brar, H. K., Jose, J., Wu, Z. & Sharma, M. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors for glioblastoma multiforme: challenges and opportunities for drug delivery. Pharmaceutics 15, 59 (2023).

Rene, C. A. & Parks, R. J. Delivery of therapeutic agents to the central nervous system and the promise of extracellular vesicles. Pharmaceutics 13, 492 (2021).

Gallego, O. Nonsurgical treatment of recurrent glioblastoma. Curr. Oncol. 22 (4), e273–281 (2015).

Sathornsumetee, S. & Rich, J. N. New approaches to primary brain tumor treatment. Anticancer Drugs. 17 (9), 1003–1016 (2006).

Xu, Y. Y., Gao, P., Sun, Y. & Duan, Y. R. Development of targeted therapies in treatment of glioblastoma. Cancer Biol. Med. 12 (3), 223–237 (2015).

Barnabas, W. Drug targeting strategies into the brain for treating neurological diseases. J. Neurosci. Methods. 311, 133–146 (2019).

Peyressatre, M., Prével, C., Pellerano, M. & Morris, M. C. Targeting cyclin-dependent kinases in human cancers: from small molecules to peptide inhibitors. Cancers (Basel). 7 (1), 179–237 (2015).

Toogood, P. L. et al. Discovery of a potent and selective inhibitor of cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6. J. Med. Chem. 48 (7), 2388–2406 (2005).

Finn, R. S. et al. Palbociclib and letrozole in advanced breast cancer. N Engl. J. Med. 375, 1925–1936 (2016).

Serra, F. et al. Palbociclib in metastatic breast cancer: current evidence and real-life data. Drugs Context. 8, 212579 (2019).

Brain, E. et al. Palbociclib in older patients with advanced/metastatic breast cancer: A systematic review. Target. Oncol. 19, 303–320 (2024).

Taylor, J. W. et al. Phase-2 trial of Palbociclib in adult patients with recurrent RB1-positive glioblastoma. J. Neurooncol. 140, 477–483 (2018).

van Mater, D. et al. A phase I trial of the CDK 4/6 inhibitor Palbociclib in pediatric patients with progressive brain tumors: A pediatric brain tumor consortium study (PBTC-042). Pediatr. Blood Cancer. 68, e28879 (2021).

De Gooijer, M. C. et al. P-glycoprotein and breast cancer resistance protein restrict the brain penetration of the CDK4/6 inhibitor Palbociclib. Invest. New. Drugs. 33, 1012–1019 (2015).

Martínez-Chávez, A. et al. P-glycoprotein limits ribociclib brain exposure and CYP3A4 restricts its oral bioavailability. Mol. Pharm. 16, 3842–3852 (2019).

Wilson, B. et al. Poly (n-butylcyanoacrylate) nanoparticles coated with polysorbate 80 for the targeted delivery of Rivastigmine into the brain to treat alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res. 1200, 159–168 (2008).

Wilson, B. et al. Targeted delivery of Tacrine into the brain with Polysorbate 80-coated Poly (n-butylcyanoacrylate) nanoparticles. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 70, 75–84 (2008).

Wilson, B., Paladugu, L., Priyadarshini, S. R. B. & Jenita, J. J. L. Development of albumin-based nanoparticles for the delivery of abacavir. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 81, 763–767 (2015).

Sebak, S., Mirzaei, M., Malhotra, M., Kulamarva, A. & Prakash, S. Human serum albumin nanoparticles as an efficient Noscapine drug delivery system for potential use in breast cancer: Preparation and in vitro analysis. Int. J. Nanomed. 5, 525–532 (2010).

Mariappan, T. T. et al. Estimation of the unbound brain concentration of P-glycoprotein substrates or nonsubstrates by a serial cerebrospinal fluid sampling technique in rats. Mol. Pharm. 11 (2), 477–485 (2014).

Al-Shehri, M. et al. Development and validation of an UHPLC-MS/MS method for simultaneous determination of palbociclib, letrozole and its metabolite carbinol in rat plasma and Pharmacokinetic study application. Arab. J. Chem. 13 (2), 4024–4034 (2020).

Iftikhar, S. Y., Iqbal, F. M., Hassan, W., Nasir, B. & Sarwar, A. R. Desirability combined response surface methodology approach for optimization of prednisolone acetate loaded Chitosan nanoparticles and in-vitro assessment. Mater. Res. Express. 7, 115004 (2020).

Tantra, R., Tompkins, J. & Quincey, P. Characterisation of the de-agglomeration effects of bovine serum albumin on nanoparticles in aqueous suspension. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 75, 275–281 (2010).

Troster, S. D. & Müller, U. Modification of the body distribution of poly(methylmethacrylate) nanoparticles in rats by coating with surfactants. Int. J. Pharm. 61, 85–100 (1990).

Kreuter, J., Alyautdin, R. N., Kharkevich, D. A. & Ivanov, A. A. Passage of peptides through the blood-brain barrier with colloidal polymer particles (nanoparticles). Brain Res. 674, 171–174 (1995).

Alyautdin, R. N., Gothier, D., Petrov, V. E., Kharkevich, D. A. & Kreuter, J. Analgesic activity of the hexapeptide Dalargin adsorbed on the surface of polysorbate 80-coated poly(butylcyanoacrylate) nanoparticles. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 41, 44–48 (1995). (1995).

Shen, S., Wu, Y., Liu, Y. & Wu, D. High drug-loading nanomedicines: progress, current status, and prospects. Int. J. Nanomed. 12, 4085–4109 (2017).

Yuan, F. & Et Vascular permeability in a human tumor xenograft: molecular size dependence and cutoff size. Cancer Res. 55, 3752–3756 (1995).

Muller, R. H., Jacobs, C. & Kayser, O. Nanosuspensions as particulate drug formulations in therapy, rationale for development and what we can expect for the future. Adv. Drug Deliv Rev. 47, 3–19 (2001).

Mainardes, R. M. & Evangelista, R. C. PLGA nanoparticles containing praziquantel: effect of formulation variables on size distribution. Int. J. Pharm. 290, 137–144 (2005).

Kohane, D. S., Tse, J. Y., Yeo, Y., Padera, R. & Shubina, M. Robert, L. Biodegradable polymeric microspheres and nanospheres for drug delivery in the peritoneum. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 77, 351–361 (2006).

Vila, A., Sánchez, A., Tobío, M., Calvo, P. & Alonso, M. J. Design of biodegradable particles for protein delivery. J. Control Release. 78, 15–24 (2002).

Wilson, B. et al. Chitosan nanoparticles as a novel delivery system for anti-Alzheimer’s drug Tacrine. Nanomed. Nanotech Biol. Med. 6 (1), 144–152 (2010).

Agnihotri, S. A., Mallikarjuna, N. N. & Aminabhavi, T. M. Recent advances on chitosan-based micro- and nanoparticles in drug delivery. J. Control Release. 100, 5–28 (2004).

Wilson, B., Samanta, M. K. & Suresh, B. Design and evaluation of Chitosan nanoparticles as novel drug carrier for the delivery of Rivastigmine to treat alzheimer’s disease. Ther. Deliv. 2, 599–609 (2011).

Muller, B. G., Leuenberger, H. & Kissel, T. Albumin nanospheres as carriers for passive drug targeting: an optimized manufacturing technique. Pharm. Res. 13, 32–37 (1996).

Costa, P. & Lobo, S. Modeling and comparison of dissolution profiles. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 13 (2), 123–133 (2001).

Langer, K. et al. Optimization of the Preparation process for human serum albumin (HAS) nanoparticles. Int. J. Pharm. 257, 169–180 (2003).

Douglas, S. J., Illum, L., Davis, S. S. & Kreuter, J. Particle size and size distribution of poly(butyl-2-cyanoacrylate) nanoparticles. J. Col Interf Sci. 101, 49–58 (1984).

Lenaerts, V. Et al. In vivo uptake of poly(isobutylcyanoacrylate) nanoparticles by the rat liver kupffer, endothelial and parenchymal cells. J. Pharm. Sci. 73, 980–982 (1984).

Chiannilkulchai, N., Ammoury, N., Caillou, B., Devissageut, J. & Couvreur, P. Hepatic tissue distribution of doxorubicin loaded nanoparticles after i.v. Administration in reticulosarcoma M 5076 metastases-bearing mice. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 26, 122–126 (1990).

Löbenberg, R., Araujo, L., von Brisen, H., Rodgers, E. & Kreuter, J. Body distribution of Azidothymidine bound to hexyl-cyanoacrylate nanoparticles after i.v. Injection to rats. J. Control Release. 50, 21–30 (1998).

Borchard, G., Audus, K. L., Shi, F. & Kreuter, J. Uptake of surfactant-coated poly(methylmethacrylate)-nanoparticles by bovine brain microvessel endothelial cell monolayers. Int. J. Pharm. 110, 29–35 (1994).

Wilson, B., Lavanya, Y., Priyadarshini, S. R. B., Ramasamy, M. & Jenita, J. J. L. Albumin nanoparticles for the delivery of gabapentin: preparation, characterization and pharmacodynamic studies. Int. J. Pharm. 473, 73–79 (2014).

Vishwanath, K., Wilson, B. & Geetha, K. M. Nanoparticle-based drug delivery across the blood-brain barrier for treating malignant brain glioma. Open. Nano. 10, 100128 (2023).

Wilson, B., Alobaid, B. N. M., Geetha, K. M. & Jenita, J. L. Chitosan nanoparticles to enhance nasal absorption and brain targeting of sitagliptin to treat alzheimer’s disease. J. Drug Deliv Sci. Technol. 61, 102176 (2021).

Vishwanath, K., Wilson, B., Geetha, K. M. & Murugan, V. Polysorbate 80-coated albumin nanoparticles to deliver Paclitaxel into the brain to treat glioma. Ther. Deliv. 14, 193–206 (2023).

Geetha, K. M., Shankar, J. & Wilson, B. Potential applications of nanomedicine for treating parkinson’s disease. J. Drug Deliv Sci. Technol. 66, 102793 (2021).

Wilson, B. & Geetha, K. M. Neurotherapeutic applications of nanomedicine for treating alzheimer’s disease. J. Control Release. 325, 25–37 (2020).

Alyautdin, R. N. et al. Delivery of loperamide across the blood-brain barrier with polysorbate 80-coated poly(butylcyanoacrylate) nanoparticles. Pharm. Res. 14, 325–328 (1997).

Alyautdin, R. N. et al. Significant entry of tubocurarine into the brain of rats by adsorption to polysorbate 80-coated poly(butylcyanoacrylate) nanoparticles: an in situ brain perfusion study. J. Microencpsul. 15, 67–74 (1998).

Gulyaev, A. E. et al. Significant transport of doxorubicin into the brain with polysorbate 80-coated nanoparticles. Pharm. Res. 16, 1564–1569 (1996).

Sun, W., Xie, C. & Wang, H. Specific role of polysorbate 80 coating on the targeting of nanoparticles to the brain. Biomaterials 25, 3065–3071 (2004).

Kreuter, J. Nanoparticle systems for brain delivery of drugs. Adv. Drug Deliv Rev. 47, 65–81 (2001).

Kreuter, J. et al. Covalent attachment of Apolipoprotein A-I and Apolipoprotein B-100 to albumin nanoparticles enables drug transport into the brain. J. Control Release. 118, 54–58 (2007).

Anonymous. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2005/21660_ABRAXANE_approv.PDF. (2005). Accessed on 13th April 2024.

Wilson, B., Geetha, K. M., Diveskar, K., Jenita, J. L. & Premakumari, K. B. Sagar, G. Albumin nanoparticle enhances oxaliplatin concentration in the colorectal region with increased efficacy. BioNanoScience 15, 1–10 (2025).

Wilson, B., Ambika, T. V., Dharmeshkumar, P., Jenita, J. J. L. & Priyadarshini, S. R. B. Nanoparticles based on albumin: preparation, characterization and the use for 5-flurouracil delivery. Int. L J. Biol. Macromol. 51, 84–88 (2012).

Wilson, B. & Geetha, K. M. Artificial intelligence and related technologies enabled nanomedicine for advanced cancer treatment. Nanomed. (London). 15, 103553 (2020).

Gradishar, W. J. & Et Phase III trial of nanoparticle albumin-bound Paclitaxel compared with polyethylated castor oil-based Paclitaxel in women with breast cancer. J. Cli Oncol. 23, 7794–7803 (2005).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.V.: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing manuscript draft, Figure, and table. B. Wilson: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Supervision, Reviewing and Editing. Geetha KM: Methodology, Formal analysis, Reviewing and Editing. Kalpana D.: Methodology, Formal analysis, Reviewing and Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

In this study, the animal experiments were carried out after getting approval from Institutional Animal Ethics Committee, College of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Dayananda Sagar University, Bengaluru, India (DSU/Ph.D./IAEC/20/2018-19). The authors confirm that all the methods are reported in accordance with ARRIVE/CCSEA guidelines.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kurawattimath, V., Wilson, B., Geetha, K.M. et al. Surface functionalized albumin nanoparticles of palbociclib with amplified brain delivery for treating brain glioblastoma. Sci Rep 15, 28433 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13721-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13721-w

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Mapping two decades of nanomaterials research in glioblastoma: trends, networks, and translational insights

Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology (2025)