Abstract

This study presents, for the first time, a theoretical investigation into the static bending behaviour of a functionally graded (FG) nanobeam integrated with a piezoelectric fibre-reinforced composite (PFRC) actuator. The model uniquely combines non-local strain gradient theory with electromechanical coupling to capture nanoscale effects accurately. In accordance with non-local strain gradient theory, a size-dependent functionally gradient nanobeam with a PFRC actuator formulation that includes extra material length size elements is designed. To model the FG nanobeam, we integrate the non-local strain gradient concept with a modified shear deformation beam theory. Three equations of equilibrium are built via the virtual work approach. The impacts of the outside electrical voltage, power law index, strain gradient parameter, non-local parameter, and length-to-thickness ratio on the static deformation of the nanobeam under electrical and mechanical loads are thoroughly investigated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fibre-reinforced composites have gained prominence in the aerospace, marine, aeronautics, and automotive industries in the past few decades. These composites can be customized to satisfy specific material requirements, such as high strength, low density, high damping, high stiffness, and high chemical and thermal shock resistance.

Designing materials with a minimum of two simultaneous interactions among electric, magnetic, elastic, and thermal materials is essential in manufacturing and engineering since they enable the feasibility and innovative usage of multipurpose devices.

Piezoelectric fibre-reinforced composites (PFRCs) have emerged as novel intelligent materials. The homogeneous piezoelectric fibres in PFRCs are longitudinally strengthened in an epoxy matrix structure. PFRCs can serve as actuators and sensors for adaptive material systems and structural health monitoring. These structures can be utilized within nanoelectromechanical structures for a variety of intelligent devices such as actuators, generators, sensors, transducers, and resonators.

Functionally graded materials (FGMs) have become common in nanoscale structures such as nanosensors, solar cells, artificial structures, and nanoelectromechanical systems. FGMs offer various advantages, namely, durability against abrasion, extreme bearing capacity, and extreme temperature capability. These materials are composed of multiple elemental components, the most prevalent being ceramics and metals. Several studies have been carried out on functionally gradient beams, plates, and shells1,2,3. Many researchers have been interested in incorporating PFRC layers into composite structures4,5,6,7,8,9,10. The mechanical properties of nanostructures have been extensively addressed in published research11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20.

Given the experimental challenges and high costs associated with nanoscale studies, the mechanical behaviour of nanodevices is often investigated through mathematical modelling. However, classic elasticity theory is inadequate for capturing size-dependent phenomena at the nanoscale, as it does not account for the long-range interatomic interactions inherent in nanostructured materials. As a result, conventional continuum mechanics have been extended to incorporate size effects through advanced theories.

Among these theories, various non-local elasticity formulations have been proposed, including Eringen’s non-local theory, strain gradient theory, surface stress theory, couple stress theory, and modified couple stress theory21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29. These models introduce internal length scale parameters that enable a more accurate representation of mechanical responses at reduced dimensions. In particular, Lim et al.7 developed non-local strain gradient theory (NSGT), which integrates two length scale parameters to capture non-local and gradient effects simultaneously. Notably, by setting the strain gradient parameter to zero, NSGT reduces to the non-local elasticity theory, and vice versa, demonstrating its versatility in modelling nanoscale mechanics.

Several investigators have utilized NSGT to examine the dynamic and static behaviours of nanostructures. Tang et al.30 addressed the static characteristics of micro- and nanobeams by adopting an overall strain gradient beam framework that accounts for shear and normal deformation interaction implications. Ebrahimi and Barati31 evaluated the vibration properties of FG viscoelastic nanobeams via NSGT and in hygrothermal environments. Rajasekeran and Khaniki32 employed the finite element approach to look at the bending, vibration, and buckling of a small-scale beam within the context of NSGT. Lv et al.33 adopted the NSGT to study the effects of material imperfections on the nonlinear vibration performance of implanted FG nanobeams. Papargyri-Beskou et al.34 examined the stability and bending of nanobeams via the Aifantis strain gradient theory. Aydogdu35 used generic non-local beam theory to investigate the vibration, bending, and buckling of nanobeams. Aghababaei and Reddy36 employed a non-local linear elasticity model to examine the vibration and bending of a nanoplate. Komeili et al.37 studied the thermoelectromechanical performance of functionally graded piezoelectric beams via a finite element model.

Chu et al.38 incorporated generalized strain gradient theory and explicitly introduced the concept of a physically neutral surface, which may deviate from the geometric mid-surface because of material gradation. This shift significantly influences the electromechanical behaviour, particularly under flexoelectric coupling. Ding et al.39 underlined the need to examine the neutral surface position rather than assume that it is at the geometric centre. They reduce the stretching–bending coupling effects induced by asymmetric material distributions, resulting in more precise predictions of nonlinear vibration properties.

Jalaei et al.40 investigated the viscoelastic transient response of functionally graded nanobeams with magnetic imperfections and employed advanced modelling to capture time-dependent behaviour under magnetic fields. Numanoğlu et al.41 presented a dynamic analysis of nanorods, focusing on size-dependent effects through non-local elasticity theory and contributing to the understanding of nanoscale mechanical behaviour. In their paper, Civalek et al.42 analysed the forced vibration response of composite beams reinforced with carbon nanotubes, highlighting the mechanical advantages of nanocomposite materials. Marinca et al.43 explored the nonlinear forced vibration of functionally graded nanobeams by incorporating non-local strain gradient theory, mechanical impact, electromagnetic actuation, and nonlinear foundation effects, providing a comprehensive nonlinear dynamic model.

Lieu et al.44 combined a non-local theory with third-order shear deformation theory to model the static bending and buckling of FG sandwich nanobeams. Additional studies on the mechanical features of nanoscale structures impacted by electric strain have been published45,46,47,48.

Several studies have provided significant insights into the behaviour of functionally graded porous nanoplates and micro/nanobeams analysed via non-local strain gradient theories. For example, the static stability under various in-plane loads and boundary conditions has been examined, highlighting the influence of porosity distributions and size effects on the mechanical response of nanostructures. These works have addressed size-dependent effects and material gradation, offering enhanced modelling accuracy for nanoscale and composite elements49,50,51,52.

Recently, Alghanmi53,54 examined the bending of FG nanoplates by applying NSGT and four unknown shear theories.

In accordance with this review, several notable studies on the incorporation of PFRC layers into composite structures have been published. In addition, different studies on nanostructures have been conducted. To the best of the author’s knowledge, this is the first attempt to explore the static bending behaviour of an FG nanobeam integrated with a PFRC actuator via the NSGT. This novel coupling of a material system and advanced size-dependent theory provides an accurate and comprehensive framework for understanding electromechanical interactions at the nanoscale. Unlike previous models that consider either FG structures or piezoelectric effects separately, the present study accounts for the dual influence of nonlocality and strain gradient effects, alongside piezoelectric actuation.

Additionally, the numerical results offer detailed insights into how variations in the electric voltage, power-law index, strain gradient parameter, non-local parameter, and aspect ratio affect the deformation and stress responses of the system.

These findings are not only academically significant but also practically applicable in designing advanced nanoelectromechanical system (NEMS) devices such as nanoactuators, sensors, energy harvesters, and biomedical devices. The results demonstrate how smart design choices at the nanoscale can dramatically influence mechanical performance, making this investigation a valuable reference for researchers and engineers working on smart nanostructures.

This study has strong practical relevance in the design of advanced NEMSs. The proposed FG nanobeam integrated with a PFRC actuator can be effectively used in nanoactuators and nanosensors requiring high precision and electromechanical responsiveness. It is also suitable for nanoscale energy harvesting, converting mechanical input into electrical energy.

The model supports applications in soft robotics and adaptive surfaces, where controlled deformation is essential. Furthermore, its sensitivity to mechanical and electrical loads makes it ideal for force and pressure sensing in biomedical and wearable systems. These applications highlight the importance of accurate modelling at the nanoscale for smart multifunctional devices.

Finally, the results of this study were obtained by applying the modified shear deformation theory. Although more complex than traditional models, this theory offers significant accuracy improvements in predicting transverse shear deformation without requiring shear correction factors.

Unlike classic or even third-order shear deformation theories, this approach captures both the nonlinearity in shear distribution and the coupling behaviour in functionally graded nanobeams more effectively, especially at small scales where gradients and electromechanical interactions are prominent.

Theory and formulation

Model description

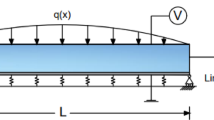

Figure 1 shows an FG nanobeam with dimensions of \(\:l,\:b,\) and \(\:h\). The FG nanobeam is connected to a PFRC layer of thickness \(\:{h}_{p}\), which functions as an actuator.

The Cartesian system \(\:(x,\:y,\:z)\) is utilized, with the origin point situated in the centre of the porous FG plate.

The essential features of the material, such as Young’s modulus \(\:E\), are defined as follows (Bao and Wang55:

The letters \(\:c\) and \(\:m\) represent ceramic and metal, respectively. The letter \(\:k\) (\(\:k\ge\:0\)) symbolizes the exponent of the power law.

This beam is exposed to an electrical potential \(\:\psi\:\) and a mechanical load \(\:q\left(x\right)\). The electric potential variations are identified as (Ray and Sachade14).

where \(\:{\psi\:}_{0}\) symbolizes the electric voltage applied on the PFRC material in the \(\:z\)-direction.

Nonlocal strain gradient theory

The stress field combines the two types of non-local elastic stress domains, as does the strain gradient stress area. The stress can be described as (Lim et al.7)

The stresses \(\:{\sigma\:}_{ij}^{\left(0\right)}\) and \(\:{\sigma\:}_{ij}^{\left(1\right)}\) refer to the strain \(\:{\varepsilon\:}_{ij}\) and the strain gradient \(\:\nabla\:{\varepsilon\:}_{ij}\), respectively, and are established by7

in which \(\:l\) is the nanobeam length. The first- and second-order non-local parameters are designated \(\:{e}_{0}a\) and \(\:{e}_{1}a\), respectively. \(\:{\alpha\:}_{0}\) is the fundamental attenuation kernel function associated with the nonlocality impact of the Euclidean distance between point \(\:x\) and its nearby points \(\:{x}^{{\prime\:}}\) within the domain \(\:V\).

The \(\:{\alpha\:}_{1}\) kernel function describes the nonlocal influence of the first-order strain gradient field. \(\:{e}_{0}\) and \(\:{e}_{1}\) are non-local material constants that can be used to calibrate theoretical and experimental data, whereas \(\:a\) is an internal characteristic length.

where \(\:{c}_{ijkl}\) denotes the elastic tensor. If the non-local functions \(\:{\alpha\:}_{0}(x,{x}^{{\prime\:}},{e}_{0}a)\) and \(\:{\alpha\:}_{1}(x,{x}^{{\prime\:}},{e}_{1}a)\) match Eringen’s requirements21, the fundamental relationship of NSGT assumes the next construction

where \(\:{\nabla\:}^{2}=\frac{{\partial\:}^{2}}{{\partial\:x}^{2}}+\frac{{\partial\:}^{2}}{{\partial\:y}^{2}}\). Considering \(\:{e}_{1}={e}_{0}=e\) and omitting terms with order \(\:O\left({\nabla\:}^{2}\right)\), the constitutive relationship in Eq. (6) may be recast as (Lim et al.7)

The parameters \(\:\eta\:={\left(ea\right)}^{2}\) and \(\:\lambda\:={l}^{2}\) represent the nonlocality and strain gradient terms of size, respectively. The NSGT measures the stress (\(\:{\sigma\:}_{ij}\)) and electric displacement (\(\:{D}_{i}\)) as56,57,58

Here, \(\:{c}_{ijkl}\), \(\:{e}_{kij}\), and \(\:{\kappa\:}_{ik}\:\)are the elastic stiffness coefficients, piezoelectric coefficients, and dielectric permittivity constants, respectively. \(\:{E}_{k}\) denotes the electrical field components. Thus, the constitutive equation for the isotropic linear FG nanobeam can be expressed as56,57,58

where

where \(\:\nu\:\) and \(\:E\left(z\right)\) are the Poisson’s ratio and Young’s modulus, respectively. The constitutive equations for the PFRC layer are considered as56,57,58

\(\:{c}_{ij}^{p}\) specifies the stiffness constants. The electrical components of \(\:{E}_{i}\) are described as

Displacement function

In accordance with the revised shear deformation theory proposed by Vo and Thai59, the field of displacement at every point of the nanobeam is presented in the following form:

in which \(\:{w}_{b}\) and\(\:\:{w}_{s}\) measure the bending and shear components of the lateral displacements resulting from the bending and shear forces, whereas \(\:u\) represents the axial displacement. The shape function is identified as60

The strain shape function in Eq. (15), adopted from Thai and Kim60, offers higher accuracy by satisfying zero transverse shear stress at beam surfaces without requiring a correction factor. This function enhances the accuracy of shear strain representation for both thin and thick beams, making it more appropriate for nanoscale modelling than classic approximations are.

Referring to the displacement field offered in Eq. (14), the strain equations can be interpreted as

Governing equations

Following Hamilton’s law, the resulting governing formulae were developed:

Combining Eqs. (13–16) with Eq. (17) yields

where the stress resultants \(\:N,\:M,\:S,\) and \(\:Q\) are identified as

The equilibrium formulae of the studied theory are constructed through applying the integration by parts and placing the coefficients of \(\:(\delta\:u,\delta\:{w}_{b},\delta\:{w}_{s})\) to zero individually:

The boundary conditions, which represent the general form derived from the current theory and allow either displacements or their corresponding force resultants to be specified depending on the physical constraints at the beam ends, are as follows:

Coupled with the NSGT as described in Eqs. (9) and (11–12), the stress resultants in Eqs. (19–20) are established in the following manner:

where

Analytical solution

In the present investigation, an analytical solution was developed for a simply supported FG nanobeam under the following boundary conditions:

The electric potential \(\:\psi\:\) is set to zero at the beam ends to represent the grounded boundary conditions for the PFRC layer, ensuring a consistent electromechanical response in the simply supported configuration. The governing equations are theoretically solved through the Navier approach process, with displacements considered as follows:

where \(\:\alpha\:=\pi\:/l\) and \(\:(U_{m},\:{{W}_{b}}_{m},\:{{W}_{s}}_{m},\:V)\) are the unknown parameters. The mechanical load is expanded as

in which \(\:{Q}_{m}\) is defined for the uniform distributed load as follows:

Substituting Eq. (26) into Eq. (21) yields

The elements \(\:{a}_{ij}={a}_{ji}\) are given as

Numerical results

The numerical findings reported in this section are designed to illustrate the consequences of the electrical voltage, length dimension, and non-local components on the bending of an FG nanobeam linked to a PFRC actuator.

The FG nanobeam has dimensions of \(\:l=10\) nm, whereas the PFRC layer has a thickness of \(\:{h}_{p}=0.1\:h\). The properties of the FG material are presumed to be

The elastic and piezoelectric characteristics of the PFRC layer were determined by Mallik and Ray8.

The mechanical load used in the computations is \(\:{q}_{0}=1\:\text{N}/{\text{m}}^{2}.\).

Verification study

Tables 1, 2 and 3 compare the current analysis to the previous studies of Zemeri et al.41 and Chaht et al.42, omitting the PFRC layer and examining only the non-local parameter \(\:\eta\:\).

Across all the tables, the displacement \(\:w\) increases with the non-local parameter\(\:\eta\:\)and decreases with the power law variable \(\:k\). This behaviour is consistent regardless of the ratio \(\:l/h\).

The findings from the present study (using HSDT) align closely with those from Zemri et al.61 (TSDT) and Chaht et al.62 (SSDT), reinforcing the reliability of these models in predicting the transverse displacement of FG nanobeams. Understanding the mechanical properties of FG nanobeams under bending requires careful consideration of both the \(\:\eta\:\) and \(\:k\) parameters during design and analysis.

Parametric study

This section presents a numerical examination of the bending action of an FG nanobeam linked with a PFRC layer. The following formulae are utilized to calculate the dimensionless displacement and stresses:

Table 4 shows the transverse displacement and stresses of an FG nanobeam alongside a top PFRC layer at different electric voltages and fixed non-local parameters (\(\:\eta\:,\:\lambda\:\)). The results are categorized according to the aspect ratios \(\:l/h=10,\:20,\:100\). For \(\:l/h=10\), the displacement varies as the voltage changes from \(\:V=5\) to \(\:V=-5\). This indicates a significant change in behaviour under applied voltage.

At \(\:l/h=10\), the displacement also decreases with increasing negative voltage. For \(\:l/h=100\), the displacement remains relatively consistent, with values of approximately 0.2699 to 0.2621 across different voltages, indicating less sensitivity to electric voltage.

For a fixed voltage, increasing the power index \(\:k\) tends to increase the displacement. For example, at \(\:V=5\) and \(\:l/h=20\), the displacement increases from 0.3657 (at \(\:k=0.1\)) to 0.4919 (at \(\:k=0.5\)).

With respect to the variation in axial stress, for \(\:l/h=10\), the axial stress ranges from \(\:-0.1037\:\:\) (at \(\:V=5\)) to 0.2371 (at \(\:V=-5\)), indicating a significant increase in stress magnitude with negative voltage. At \(\:l/h=100\) and \(\:V=-5\), the axial stress can reach as high as 12.4441. With a fixed voltage, the normal stresses increase significantly as \(\:k\) increases. This finding highlights the increase in the stress response resulting from the electromechanical coupling effects.

With respect to the variation in shear stress, the shear stress follows a similar pattern. At \(\:l/h=10\) and \(\:k=0.1\), the shear stress at \(\:V=5\) is 18.7538, which decreases to \(\:-18.7328\) at \(\:V=-5\). The applied voltage has a substantial effect on the structural integrity of the FG nanobeam, as evidenced by the maximum shear stress of 92.8820 for \(\:l/h=100\) at \(\:V=-5\). However, as the voltage increases, the shear stress can reach significant negative values, indicating a robust response under mechanical loading.

Table 5 shows the results of the transverse displacement and stresses under varying conditions of utilized voltage \(\:V,\) strain gradient variable \(\:\lambda\), and non-local variable \(\:\eta.\) The applied voltage substantially influences the transverse displacement, with a positive voltage increasing the displacement, zero voltage producing a neutral state, and negative voltage decreasing the displacement. Increasing V leads to a shift in normal stress values, making them more positive or negative depending on the sign of \(V.\) The shear stress follows a similar trend, where a higher positive voltage increases its value in the positive range, whereas a negative voltage leads to an inverse effect.

As the strain gradient variable increases, the transverse displacement decreases, indicating increased stiffness, whereas both the normal stress and shear stress slightly decrease. This demonstrates that higher \(\:\lambda\:\) values increase the rigidity of the beam and reduce stress concentrations, increasing its resistance to deformation and stress. As \(\:\eta\:\) increases, the transverse displacement increases, indicating greater flexibility, whereas the normal stress slightly decreases, and the shear stress slightly increases. This shows that higher \(\:\eta\:\) values enhance the beam’s non-local effects, leading to greater deformation and altered stress distribution, reflecting increased material flexibility at the nanoscale.

Figures 2, 3 and 4, and 5 demonstrate how different factors (\(\:V,\:\:\lambda\:,\:\:\eta\:,\:\:k\)) alter the displacement profile along the thickness of an FG nanobeam.

Figure 2 shows the effect of the applied electric voltage V on the transverse displacement. As V increases, the electromechanical coupling intensifies, leading to greater deflections along the beam. Figure 3 presents the influence of the strain gradient parameter \(\:\lambda\:\) on the displacement profile. An increase in \(\lambda\) enhances the stiffness of the nanobeam, which reduces the magnitude of transverse displacement along the length.

Figure 4 shows the effect of the non-local parameter \(\:\eta\:\). Higher values of \(\:\eta\:\) result in a more pronounced displacement, reflecting the softening behaviour induced by non-local interactions. Figure 5 explores the impact of the power-law parameter \(\:k\), which represents the material gradation. Increasing \(\:k\) generally leads to higher displacement magnitudes because of the more pronounced gradation effect in the FG material.

The variations in the axial stresses \(\:{\sigma\:}_{x}\) and the transverse shear stresses \(\:{\tau\:}_{xz}\) along the thickness of the FG nanobeam as a function of the electric voltage \(\:V\) with fixed parameters \(\:(k=1,\:\eta\:=2,\:\lambda\:=1,a/h=10)\) are depicted in Fig. 6a and b. Figure 6a shows that \(\:{\sigma\:}_{x}\) distributions tend to be nonlinear, with stress concentrations adjacent to surfaces, particularly at the interface with the PFRC layer. As the electrical charge \(\:V\) increases, the axial stress distribution may have a different pattern, potentially leading to greater tensile or compressive stresses depending on the material features. Depending on the specific gradation and material characteristics of the FG nanobeam, the spread of \(\:{\tau\:}_{xz}\) to the mid-plane might be symmetric or asymmetric. Figure 6b shows that the presence of the PFRC layer could further impact this distribution, resulting in different stress concentrations at the top layer, where the PFRC layer is located. The impacts of the strain gradient parameter \(\:\lambda\:\) on the variation in the stresses \(\:{\sigma\:}_{x}\) and the stresses \(\:{\tau\:}_{xz}\) through the thickness of the FG nanobeam with the fixed variables \(\:(k=2,\:\eta\:=1,\:V=0.1,l/h=10)\) are illustrated in Fig. 7a and b.

The axial stress varies considerably near the surface and diminishes towards the centre of the beam. As \(\:\lambda\:\) increases, the surface stresses may become more intense, resulting in larger stress gradients and strain gradient effects. The shear stress is generally greater towards the nanobeam core and lower at the boundaries. As \(\:\lambda\:\) increases, the shear stress may redistribute more sharply, possibly due to the greater sensitivity of the FG material to strain gradients in the transverse direction.

Generally, increasing \(\:\lambda\:\) decreases the axial and transverse shear stresses in the FG nanobeam. This implies that greater strain gradient effects (i.e., increased \(\:\lambda\:\)) reduce the material’s internal force response, resulting in lower stress concentrations.

Figure 8a and b show the variation in the axial stresses \(\:{\sigma\:}_{x}\) and the transverse shear stresses \(\:{\tau\:}_{xz}\) along the thickness of the FG nanobeam in terms of the non-local parameter \(\:\eta\:\) with the fixed variables \(\:(k=2,\:\lambda\:=1,\:V=0.1,l/h=10)\).

Increasing the non-local parameter \(\:\eta\:\) causes an increase in \(\:{\sigma\:}_{x}\) through the thickness of the FG nanobeam. This means that as nonlocality increases, so do the material’s internal tensions. An increase in \(\:\eta\:\) indicates that nonlocal influences increase the material’s responsiveness to applied forces, leading to stiffer behaviour and higher stress magnitudes. The transverse shear stress \(\:{\tau\:}_{xz}\) increases as \(\eta\) increases. This behaviour implies that larger non-local impacts increase the resistance of a material to shear forces.

Figure 9a and b demonstrate how the homogeneity index \(\:k\) (\(\eta\:=2,\:\lambda\:=4,\:V=2,l/h=10\)) changes the variance of the axial and transverse shear stresses within the thickness of the FG nanobeam.

The material gradation, represented by \(k\), has a direct effect on the distribution of axial stress \(\:{\sigma\:}_{x}\). As \(\:k\) increases, the material properties of the FG nanobeam become more heterogeneous across its thickness. A greater \(k\) value causes a steeper gradient in material characteristics, resulting in more substantial fluctuations in axial stress. The difference in stiffness between the beam and the PFRC layer causes more significant fluctuations in \(\:{\sigma\:}_{x}\) with increasing thickness, particularly near the interface.

The power law variable \(k\) also affects the transverse shear stress \(\:{\tau\:}_{xz}\). As \(k\) increases, the stress distribution along the thickness may display sharper transitions, especially at the surfaces where the material characteristics change more quickly. The stress distribution may concentrate on the outer surfaces or interfaces, especially at larger \(k\) values, causing stress concentrations or regions of increased shear stress, depending on the elastic gradient of the material.

The variations in the transverse displacement \(\:w\) as a function of \(\:l/h\) for various factors (\(\:V,\:\:\lambda\:,\:\:\eta\:,\:\:k\)) are illustrated in Figs. 10, 11, 12 and 13. Figure 10 shows that smaller \(\:l/h\) values result in a thicker nanobeam, which is more responsive to the applied electric voltage. In this range, thicker nanobeams deform more due to greater electrostatic forces, leading to a significant increase in \(w\) with increasing voltage. This is because a thicker nanobeam can store more energy in the form of strain in response to applied electric fields. As the \(\:l/h\) ratio increases, the nanobeam thins. The displacement induced by the same voltage becomes less noticeable. This reduced sensitivity to electric voltage in narrower beams is most likely due to an increase in beam stiffness as the thickness decreases. A thinner nanobeam is more structurally stiff in relation to its length, resulting in a lesser increase in displacement even when the same voltage is applied.

Figure 11 reveals that the strain gradient becomes more noticeable for smaller \(\:l/h\) ratios and thicker beams. In this range, the transverse displacement \(w\) decreases dramatically as \(\lambda\) increases. This implies that for thicker beams, the strain gradient stiffens the material, limiting its capacity to deform. Thicker beams are more susceptible to microstructural effects; therefore, even slight increases in \(\lambda\) result in noticeable displacement decreases.

Figure 12 shows that for smaller \(\:l/h\) ratios and thicker beams, the impact of the non-local parameter \(\eta\) is increasingly prominent. As \(\eta\) increases, so does the transverse displacement \(w\). This suggests that for thicker beams, the addition of non-local effects softens the material, making it more flexible under the same conditions. The increase in the non-local parameter reduces the beam’s stiffness, allowing it to have larger displacements.

Figure 13 shows that for smaller \(\:l/h\) ratios (thicker beams), the transverse displacement \(w\) increases with the power law variable \(k\). Larger \(\:l/h\) ratios (thinner beams) increase the transverse displacement \(w\) with increasing \(k\), but the effect is less pronounced than that of thicker beams. Thinner beams, despite being more flexible due to their geometry, experience less displacement increase from changes in \(k\), as their thinner structure is already highly flexible, and the impact of material gradation is less substantial. However, even with thinner beams, increasing \(k\) leads to larger displacements.

Conclusions

The transverse displacement and stresses of the FG nanobeams integrated with PFRC layers were found to be highly sensitive to the applied electric voltage. As the aspect ratio increased, a reduction in displacement sensitivity and an increase in stress sensitivity were observed, indicating different mechanical behaviours under varying conditions. The bending response was significantly affected by the applied voltage, power-law index \(\:k\), and length-to-thickness ratio. Non-local effects, especially the parameter \(\:\eta\:\), led to an increase in both axial \(\:{\sigma\:}_{x}\) and shear \(\:{\tau\:}_{x}\) stresses, resulting in a stiffer mechanical response than that predicted from classic elasticity. The interactions among the electric voltage \(\:V\), strain gradient parameter \(\:\lambda\:\), non-local parameter \(\:\eta\:\), and power-law index \(\:k\) highlight the complex electromechanical behaviour in FG nanobeams. These findings underscore the necessity of incorporating size-dependent effects in the design of nanoscale structures for actuation and sensing applications.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Chu, L., Dui, G., Ju, C. & Zheng, L. Thermally induced nonlinear dynamic analysis of temperature-dependent functionally graded flexoelectric nanobeams based on nonlocal simplified strain gradient elasticity theory. Eur. J. Mech. Solids. 82, 103999 (2020).

Chu, L., Li, Y. & Dui, G. Nonlinear analysis of functionally graded flexoelectric nanoscale energy harvesters. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 167, 105282 (2020).

Zhou, F., Chu, L. & Dui, G. Model and performance analysis of energy conversion in functionally graded flexoelectric semiconductor nanostructures. Appl. Math. Model. 135, 729–744 (2024).

Ekinci, K. L. & Roukes, M. L. Nanoelectromechanical systems. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 76, 061101 (2005).

Bhushan, B. Nanotribology and nanomechanics of MEMS/NEMS and biomems/bionems materials and devices. Microelectron. Eng. 84, 387–412 (2007).

Nami, M. R. & Janghorban, M. Static analysis of rectangular nanoplates using trigonometric shear deformation theory based on nonlocal elasticity theory. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 4, 968–973 (2013).

Lim, C. W., Zhang, G. & Reddy, J. N. A higher-order nonlocal elasticity and strain gradient theory and its applications in wave propagation. J. Mech. Phys. Solids. 78, 298–313 (2015).

Mallik, N. & Ray, M. C. Effective coefficients of piezoelectric fiber-reinforced composites. AIAA J. 41, 704–710 (2003).

Ray, M. C. & Mallik, N. Performance of smart damping treatment using piezoelectric fiber-reinforced composites. AIAA J. 43, 184–193 (2005).

Panda, S. & Ray, M. C. Nonlinear finite element analysis of functionally graded plates integrated with patches of piezoelectric fiber reinforced composite. Finite Elem. Anal. Des. 44, 493–504 (2008).

Shiyekar, S. M. & Kant, T. Higher order shear deformation effects on analysis of laminates with piezoelectric fibre reinforced composite actuators. Compos. Struct. 93, 3252–3261 (2011).

Abad, F. & Rouzegar, J. An exact spectral element method for free vibration analysis of FG plate integrated with piezoelectric layers. Compos. Struct. 180, 696–708 (2017).

Mallik, N. & Ray, M. C. Exact solutions for the analysis of piezoelectric fiber reinforced composites as distributed actuators for smart composite plates. Int. J. Mech. Mater. Des. 1, 347–364 (2004).

Ray, M. C. & Sachade, H. M. Finite element analysis of smart functionally graded plates. Int. J. Solids Struct. 43, 5468–5484 (2006).

Li, L. & Hu, Y. Nonlinear bending and free vibration analyses of nonlocal strain gradient beams made of functionally graded material. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 107, 77–97 (2016).

Barretta, R., Feo, L., Luciano, R., de Sciarra, F. M. & Penna, R. Functionally graded Timoshenko nanobeams: a novel nonlocal gradient formulation. Compos. Part. B Eng. 100, 208–219 (2016).

Allahyari, E., Asgari, M. & Pellicano, F. Nonlinear strain gradient analysis of nanoplates embedded in an elastic medium incorporating surface stress effects. Eur. Phys. J. Plus. 134, 191 (2019).

Xu, X., Karami, B. & Janghorban, M. On the dynamics of nanoshells. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 158, 103431 (2021).

Civalek, Ö. & Demir, C. A simple mathematical model of microtubules surrounded by an elastic matrix by nonlocal finite element method. Appl. Math. Comput. 289, 335–352 (2016).

Behrouz, A. & Wang, Q. A review on the application of nonlocal elastic models in modeling of carbon nanotubes and graphenes. Springer Ser. Mater. Sci. 188, 57–82 (2014).

Eringen, A. C. On differential equations of nonlocal elasticity and solutions of screw dislocation and surface waves. J. Appl. Phys. 54, 4703–4710 (1983).

Eringen, A. C. & Edelen, D. On nonlocal elasticity. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 10, 233–248 (1972).

Yang, F., Chong, A. C. M., Lam, D. C. C. & Tong, P. Couple stress based strain gradient theory for elasticity. Int. J. Solids Struct. 39, 2731–2743 (2002).

Lou, J., He, L., Du, J. & Wu, H. Buckling and post-buckling analyses of piezoelectric hybrid microplates subject to thermo–electro-mechanical loads based on the modified couple stress theory. Compos. Struct. 153, 332–344 (2016).

Thai, H. T. & Vo, T. P. A nonlocal sinusoidal shear deformation beam theory with application to bending, buckling, and vibration of nanobeams. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 54, 58–66 (2012).

Lu, L., Xingming, G. & Jianzhong, Z. A unified size-dependent plate model based on nonlocal strain gradient theory including surface effects. Appl. Math. Model. 68, 583–602 (2019).

Thanh, C. L., Tran, L. V., Vu-Huu, T., Nguyen-Xuan, H. & Abdel-Wahab, M. Size-dependent nonlinear analysis and damping responses of FG-CNTRC micro-plates. Comput. Meth Appl. Mech. Eng. 353, 253–276 (2019).

Farajpour, A., Howard, C. Q. & Robertson, W. S. P. On size-dependent mechanics of nanoplates. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 156, 103363 (2020).

Barretta, R., Faghidian, S. A. & de Sciarra, F. M. Stress-driven nonlocal integral elasticity for axisymmetric nano-plates. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 136, 38–52 (2019).

Tang, H. et al. Coupling effect of thickness and shear deformation on size-dependent bending of micro/nano-scale porous beams. Appl. Math. Model. 66, 527–547 (2019).

Ebrahimi, F. & Barati, M. R. Hygrothermal effects on vibration characteristics of viscoelastic FG nanobeams based on nonlocal strain gradient theory. Compos. Struct. 159, 433–444 (2017).

Rajasekeran, S. & Khaniki, H. B. Bending, buckling and vibration of small-scale tapered beams. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 120, 172–188 (2017).

Lv, Z., Qiu, Z., Zhu, J., Zhu, B. & Yang, W. Nonlinear free vibration analysis of defective FG nanobeams embedded in elastic medium. Compos. Struct. 202, 675–685 (2018).

Papargyri-Beskou, S., Tsepoura, K. G., Polyzos, D. & Beskos, D. E. Bending and stability analysis of gradient elastic beams. Int. J. Solids Struct. 40, 385–400 (2003).

Aydogdu, M. A general nonlocal beam theory: its application to nanobeam bending, buckling and vibration. Phys. E. 41, 1651–1655 (2009).

Aghababaei, R. & Reddy, J. N. Nonlocal third-order shear deformation plate theory with application to bending and vibration of plates. J. Sound Vib. 326, 277–289 (2009).

Komeili, A., Akbarzadeh, A. H., Doroushi, A. & Eslami, M. R. Static analysis of functionally graded piezoelectric beams under thermo-electro-mechanical loads. Adv. Mech. Eng. 3, 153731 (2011).

Chu, L., Dui, G. & Ju, C. Flexoelectric effect on the bending and vibration responses of functionally graded piezoelectric nanobeams based on general modified strain gradient theory. Compos. Struct. 186, 39–49 (2018).

Ding, J., Chu, L., Xin, L. & Dui, G. Nonlinear vibration analysis of functionally graded beams considering the influences of the rotary inertia of the cross section and neutral surface position. Mech. Based Des. Struct. Mach. 46, 225–237 (2017).

Jalaei, M. H., Thai, H. T. & Civalek, O. On viscoelastic transient response of magnetically imperfect functionally graded nanobeams. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 172, 103629 (2022).

Numanoğlu, H. M., Akgöz, B. & Civalek, O. On dynamic analysis of nanorods. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 130, 33–50 (2018).

Civalek, Ö., Akbaş, Ş. D., Akgöz, B. & Dastjerdi, S. Forced vibration analysis of composite beams reinforced by carbon nanotubes. Nanomaterials 11(3), 571 (2021).

Marinca, B., Herisanu, N. & Marinca, V. Investigating nonlinear forced vibration of functionally graded nanobeam based on the nonlocal strain gradient theory considering mechanical impact, electromagnetic actuator, thickness effect and nonlinear foundation. Eur. J. Mech. Solids. 102, 105119 (2023).

Lieu, P. V., Zenkour, A. M. & Luu, G. T. Static bending and buckling of FG sandwich nanobeams with auxetic honeycomb core. Eur. J. Mech. A-Solid. 103, 105181 (2024).

Fu, Y., Tang, X., Jin, Q. & Wu, Z. An alternative electro-mechanical finite formulation for functionally graded graphene-reinforced composite beams with macro-fiber composite actuator. Materials 14, 7802 (2021).

Chuaqui, T. R. C. & Roque, C. M. C. Analysis of functionally graded piezoelectric Timoshenko smart beams using a multiquadric radial basis function method. Compos. Struct. 176, 640–653 (2017).

Rao, M. N., Schmidt, R. & Schröder, K. U. Large Deflection electro-mechanical analysis of composite structures bonded with macro-fiber composite actuators considering thermal loads. Eng. Comput. 38(Suppl 2), 1459–1480 (2022).

Lee, A. J. & Inman, D. J. Electromechanical modeling of a bistable plate with macro-fiber composites under nonlinear vibrations. J. Sound Vib. 446, 326–342 (2019).

Omar, I. et al. Static stability of functionally graded porous nanoplates under uniform and non-uniform in-plane loads and various boundary conditions based on the nonlocal strain gradient theory. Results Eng. 25, 103612 (2025).

Sahmani, S. & Madyira, D. M. Nonlocal strain gradient nonlinear primary resonance of micro/nano-beams made of GPL reinforced FG porous nanocomposite materials. Mech. Based Des. Struct Mach. 49, 553–580 (2021).

Chen, S. X., Sahmani, S. & Safaei, B. Size-dependent nonlinear bending behavior of porous FGM quasi-3D microplates with a central cutout based on nonlocal strain gradient isogeometric finite element modelling. Eng. Comput. 37, 1657–1678 (2021).

Shahzad, M. A., Sahmani, S., Safaei, B., Basingab, M. S. & Hameed, A. Z. Nonlocal strain gradient-based meshless collocation model for nonlinear dynamics of time-dependent actuated beam-type energy harvesters at nanoscale. Mech. Based Des. Struct. Mach. 52, 3974–4008 (2023).

Alghanmi, R. A. Nonlocal strain gradient theory for the bending of functionally graded porous nanoplates. Materials 15, 8601 (2022).

Alghanmi, R. A. Hygrothermal bending analysis of sandwich nanoplates with FG porous core and piezomagnetic faces via nonlocal strain gradient theory. Nanotechnol Rev. 12, 20230123 (2023).

Bao, G. & Wang, L. Multiple cracking in functionally graded ceramic/metal coatings. Int. J. Solids Struct. 32 (19), 2853–2871 (1995).

Malikan, M. & Nguyen, V. B. Buckling analysis of piezo-magnetoelectric nanoplates in hygrothermal environment based on a novel one variable plate theory combining with higher-order nonlocal strain gradient theory. Phys. E. 102, 8–28 (2018).

Arefi, M., Kiani, M. & Zamani, M. H. Nonlocal strain gradient theory for the magneto-electro-elastic vibration response of a porous FG-core sandwich nanoplate with piezomagnetic face sheets resting on an elastic foundation. J. Sandw. Struct. Mater. 0, 1–29 (2018).

Arefi, M., Pourjamshidian, M. & Ghorbanpour Arani, A. Application of nonlocal strain gradient theory and various shear deformation theories to nonlinear vibration analysis of sandwich nano-beam with FG-CNTRCs face-sheets in electro-thermal environment. Appl. Phys. A. 123, 323 (2017).

Vo, T. P. & Thai, H. T. Vibration and buckling of composite beams using refined shear deformation theory. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 62, 67–76 (2012).

Thai, H. T. & Kim, S. E. Analytical solution of a two-variable refined plate theory for bending analysis of orthotropic Levy-type plates. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 54, 269–276 (2012).

Zemri, A., Houari, M. S. A., Bousahla, A. A. & Tounsi, A. A mechanical response of functionally graded nanoscale beam: an assessment of a refined nonlocal shear deformation theory. Struct. Eng. Mech. 54, 693–710 (2015).

Chaht, F. L. et al. Bending and buckling analyses of functionally graded material (FGM) size-dependent nanoscale beams including the thickness stretching effect. Steel Compos. Struct. 18, 425–442 (2015).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.A.A. conceived the study, developed the theoretical model, performed the analysis, and wrote the manuscript. R.A.A. also prepared all figures and reviewed the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alghanmi, R.A. Size-dependent static response of a functionally graded nanobeam attached to a piezoelectric fibre-reinforced composite actuator. Sci Rep 15, 28734 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13726-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13726-5