Abstract

Inadequate bowel preparation negatively impacts the quality of colonoscopy, potentially resulting in missed lesions and the need for repeat procedures. Although gut motility plays a key role in bowel cleansing, it is often neglected in risk prediction. This study developed and validated a predictive model and simplified scoring system that integrates gut motility parameters to identify individuals at risk of inadequate bowel preparation. A total of 1,165 patients from two hospitals were enrolled, with 815 forming the training set and 350 forming the external validation cohort. The overall rate of inadequate bowel preparation was 9.8%. Multivariate analysis revealed that altered bowel movement frequency, stool consistency based on the Bristol Stool Scale, low polyethylene glycol (PEG) volume, and delayed last bowel movement were significant predictors of poor preparation. These variables were incorporated into a user-friendly scoring system that demonstrated good discriminative ability, with area under the curve values of 0.778 and 0.774 in the training and validation cohorts, respectively. A cutoff score of 3.0 yielded a sensitivity of 75.0%, specificity of 66.9%, and a negative predictive value of 96.3% in external validation. This model provides a practical, motility-informed approach for risk stratification and personalized preparation regimens, offering potential to enhance the effectiveness and efficiency of colonoscopy in diverse clinical settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Adequate bowel preparation is crucial for the success of colonoscopy, thus preventing colorectal cancer, as it ensures clear visualization of the colonic mucosa, facilitating the detection and removal of neoplastic lesions1,2. Inadequate bowel preparation can result in missing 1/3 to 1/2 of adenomas during colonoscopy3. It also leads to incomplete procedures and increased healthcare costs due to the need for repeat colonoscopies4. Various factors, including elder age, history of abdominal surgery, constipation, diabetes, inadequate patient compliance, low volume of laxatives, long bowel-preparation-to-defecation interval, and inadequate exercise during preparation, contribute to poor preparation quality5. Predictive models integrating these factors aim to identify patients at risk of inadequate bowel preparation, enabling individualized strategies to improve outcomes6.

Gut motility plays a critical role in determining bowel preparation quality. Altered bowel movement frequency and stool consistency significantly affect the effectiveness of preparation regimens7. Constipation, often caused by gastrointestinal motility disorders, comorbidities (such as Parkinson’s disease and stroke), or medications such as opioids, antidepressants, calcium channel blockers, and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists, impair bowel motility and hinder effective preparation8,9,10. Combining gut motility parameters with clinical factors, predictive models may provide clinicians with a tailored approach to optimizing bowel preparation. Tools such as the Bristol Stool Chart offer a simple yet reliable method for assessing stool consistency and have shown promise in clinical practice11. Moreover, the regularity of daily bowel movements and the timing of the last bowel movement before colonoscopy significantly influence preparation quality12. However, the existing predictive models did not integrate gut motility assessments such as stool consistency and detailed evaluation of daily and the most recent bowel movements into predictive models for bowel preparation12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19.

This study addresses this gap by developing and validating a predictive model that integrates gut motility assessment to predict inadequate bowel preparation. Using a multicenter observational cohort, we identified significant risk factors, created a diagnostic nomogram, and developed a simplified scoring system. These tools provide a practical framework for stratifying patients by risk and personalizing bowel preparation strategies. Through rigorous validation and demonstrated clinical utility, this study offers a robust methodology to enhance colonoscopy outcomes and improve patient care.

Methods

Patients

This prospective observational study recruited multicenter cohorts, including a derivation cohort from Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital and an external validation cohort from Northern Jiangsu People’s Hospital. Consecutive patients who underwent colonoscopy were included between October 2024 and December 2024. Eligible participants were adults who completed bowel preparation with polyethylene glycol (PEG) in divided doses as per standard protocols. Exclusion criteria included a history of gastrointestinal surgery, gastrointestinal bleeding, inflammatory bowel disease, neurological conditions (e.g., Parkinson’s disease, stroke, or spinal injury), use of tricyclic antidepressants, or incomplete data.

Sample size calculation

To minimize overfitting, we calculated the minimum sample size required to develop a multivariable clinical prediction model using the criteria proposed by Riley et al.20. Based on the prevalence of inadequate bowel preparation in previous cohorts of 12% and the expected C-Index of 0.75, the minimum sample size required in the derivation cohort is 815, using up to the anticipated seven predictor parameters and with a shrinkage of 0.9 and an anticipated dropout rate of 15%. With the ratio of set sizes as 7:3, the external validation cohort required a minimum size of 350. Furthermore, we confirm that the final model development adhered to the important principle of ≥ 10 events-per-parameter (EPP). With an observed event rate of 9.9% in the derivation cohort (n = 815), yielding 81 events, and 6 predictor degrees of freedom included in the final model, we achieved an EPP of 13.5, which exceeds the recommended threshold of 10. This provides additional confidence in the stability and reliability of our model coefficients.

Bowel Preparation protocol

Patients followed a low-residue diet the day before their colonoscopy and fasted entirely on the day of the procedure. They were prescribed 2 L, 3 L, or 4 L of split-dose PEG solution based on the routine practices of their outpatient doctors, with 3 L PEG being the most common regimen. In the 3 L PEG regimen, patients consumed the first liter of PEG the night before the colonoscopy. The remaining two liters were taken in the early morning at one-hour intervals for morning procedures (8 a.m. to 12 p.m.) or late morning for afternoon procedures (2 p.m. to 5 p.m.). In the 2 L PEG regimen, the night-before dose was omitted, while in the 4 L PEG regimen, patients consumed two liters of PEG the night before at one-hour intervals. Patients self-reported the timing of their PEG intake via a questionnaire.

Colonoscopy procedure

All colonoscopies were performed by experienced endoscopists under sedation using CO₂ insufflation. During withdrawal, all endoscopists performed standard intra-procedural cleaning maneuvers, including water flushing, irrigation, and suctioning, to optimize mucosal visualization. Water-assisted techniques such as water immersion or water exchange were not used. Each examination was conducted by two endoscopists: one performed the procedure, while the other monitored real-time endoscopic images and assessed bowel cleanliness using the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale (BBPS) during withdrawal, following standard intra-procedural cleaning maneuvers21. Both endoscopists were blinded to the patient-specific factors, such as bowel movement frequency and stool consistency, and the dosage of the preparation regimen. The BBPS assessed three colonic segments (left colon, transverse colon, right colon) with scores ranging from 0 (poor) to 3 (excellent). The total score (0–9) is the sum of the segmental scores. A total BBPS < 6, or BBPS of either colonic segment < 2, defines inadequate bowel preparation. The location, diameter, and morphology of the polyps detected were documented by electronic reports and images. In cases of inadequate preparation despite maximal intra-procedural cleaning, patients were advised to undergo early repeat colonoscopy with modified bowel preparation protocols, in line with institutional practice.

Data collection

Baseline patient data were collected through structured questionnaires before the colonoscopy, including bowel movement frequency of the last 2 weeks, stool consistency (Bristol Stool Scale), and PEG dosage. Procedural data, such as colonoscopy time, BBPS scores, and polyp detection rates, were recorded by electronic reports. BBPS scores were used as the primary outcome to evaluate bowel preparation quality. Additional clinical variables, such as comorbidities and demographic details, were also documented. Decreased bowel movement was defined as < 3 times per week, and increased bowel movement was defined as > 15 times per week.

Missing Data Handling: Missingness for all predictors was shown in Table S1. Given the minimal missing data (2.4% in the derivation cohort and 0 in the validation cohort), complete-case analysis was employed.

Statistical analysis

The normality of the data distribution was assessed with the Shapiro-Wilk test. The normal distribution data are presented as mean and standard deviation, and the difference between the two groups was analyzed by t-tests. The non-normally distributed data are given as medians and interquartile ranges (IQR), and the Mann-Whitney U test was carried out to illustrate the difference between the two groups. In categorical variables, the number of each group and its proportion is described, and the difference between the two groups was compared by chi-square tests. Variables with P < 0.05 entered logistic regression analyses. In the derivation cohort, univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to identify independent predictors of inadequate bowel preparation, with results expressed as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). A diagnostic nomogram was constructed based on the significant predictors, and its performance was evaluated using calibration curves, decision curve analysis (DCA), and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. A simplified scoring system was derived from the nomogram and validated in both cohorts. Statistical analyses were conducted using R software (version 4.2.0), with a two-sided P value < 0.05 considered significant.

Results

Patient selection and cohort comparability

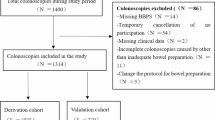

Figure 1 illustrates the patient selection process. We included 815 patients at Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital in the derivation cohort and 350 patients at Northern Jiangsu People’s Hospital in the external validation cohort. Table 1 summarizes the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the derivation and validation cohorts. There is a statistically different mean age between the validation cohort (50.5 ± 14.6 years) and the derivation cohort (48.5 ± 14.9 years, P = 0.036), but it does not felt to be clinically significant. The other variables show no significant differences, confirming the comparability of the two cohorts.

Screening predictors and developing a multivariate model in the derivation cohort

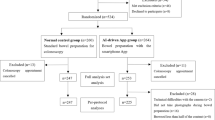

In the derivation cohort, the comparison between patients with adequate and inadequate bowel preparation revealed distinct differences (Table S2). Decreased bowel movements were notably common among those with inadequate preparation (51.9% vs. 14.7%, P < 0.001). Stool form differed significantly, with patients having inadequate preparation showing a lower mean Bristol Stool Chart (2.91 ± 1.81 vs. 3.99 ± 1.31, P < 0.001) and a higher prevalence of dry stools (48.1% vs. 12.5%, P < 0.001). Preparation volume was also a significant factor. The use of 2 L PEG was more common in patients with inadequate bowel preparation (30.9% vs. 14.9%, P < 0.001), whereas higher volumes (3 L and 4 L) were associated with better preparation quality. The timing of the last bowel movement was another critical determinant, with preparation adequacy sharply declining when the interval exceeded three days before colonoscopy (32.1% vs. 4.1%, P < 0.001). BBPS scores were significantly lower in the inadequate preparation group across all colonic regions (P < 0.001), accompanied by a reduced cecal intubation rate (86.7% vs. 100%, P < 0.001). Multivariate analysis identified several significant predictors of inadequate bowel preparation (Table S3). The model’s formula was as follows: logit (P) = -0.67 + 1.07×(decreased movement) + 1.07×(increased movement) + 1.78×(Last bowel movement ≥ 3 days before colonoscopy) − 0.35×(Bristol stool scale) − 1.31×(PEG volume of 3 L) − 1.99×(PEG volume of 4 L). Both decreased bowel movement frequency (OR = 2.91, 95% CI: 1.42–5.91, P = 0.003) and increased bowel movement frequency (OR = 2.90, 95% CI: 1.32–6.09, P = 0.006) markedly increased the risk. Notably, an interval of ≥ 3 days since the last bowel movement before colonoscopy substantially increased the likelihood of inadequate preparation (OR = 5.93, 95% CI: 2.93–12.02, P < 0.001). As measured by the Bristol Stool Scale, stool form was also associated with inadequate preparation, with an OR of 0.71 per unit increase (95% CI: 0.57–0.87, P = 0.001). The volume of PEG used was a protective factor, with 3 L and 4 L regimens significantly reducing the risk of inadequate preparation (OR = 0.27 and 0.14, respectively, both P < 0.001) compared with the 2 L regimen. Figure 2 displays a forest plot summarizing the results of multivariate logistic regression.

Construction of a diagnostic nomogram and scoring system in the derivation cohort

Figure 3 illustrates the development and performance of a diagnostic nomogram for predicting inadequate bowel preparation. The nomogram (Fig. 3a) integrates key predictive factors, offering a comprehensive risk assessment tool. The calibration curve (Fig. 3b) demonstrates excellent agreement between predicted and observed probabilities in the training cohort. The decision curve analysis (Fig. 3c) highlights the clinical utility of the model, demonstrating a significant net benefit across a wide range of threshold probabilities. A simplified scoring system was developed based on the diagnostic nomogram derived from the training set (Table 2). The scoring system incorporates key predictive factors, assigning points proportional to their contribution to the risk of inadequate preparation. Both decreased and increased bowel movement frequency were assigned scores of 3, while an interval of ≥ 3 days since the last bowel movement before colonoscopy carried the highest score of 5. Stool form, assessed by the Bristol Stool Scale, demonstrated a graded association with preparation adequacy, with scores ranging from 7 points for type 1 (hard stool) to 1 point for type 7 (watery stool). Higher PEG volumes reduced risk and were assigned negative scores (-4 for 3 L and − 6 for 4 L PEG). This scoring system simplifies risk stratification by quantifying multiple risk factors into an accessible and clinically applicable framework, facilitating decision-making in practice.

Calibration and clinical utility of the diagnostic nomogram. (a) The nomogram for predicting the probability of inadequate bowel preparation. (b) Calibration curve assessing the nomogram’s agreement between predicted and observed outcomes. (c) Decision curve analysis evaluating the clinical net benefit of the nomogram.

Diagnostic performance of the scoring system in the derivation and the validation cohort

The ROC curves evaluating the scoring system’s performance in differentiating adequate from inadequate bowel preparation, with an AUC of 0.778 (95% CI: 0.719–0.37) for the training cohort and 0.774 (95% CI: 0.685–0.863) for the validation cohort (Fig. 4a and b). To efficiently and conveniently distinguish high-risk patients by the scoring system, the cut-off value was set at > 3.0 based on the Youden Index. In the derivation cohort, the scoring system achieved a sensitivity of 75.3%, a specificity of 67.2%, a positive likelihood ratio (PLR) of 2.29, and a negative likelihood ratio (NLR) of 0.37, with a negative predictive value (NPV) of 96.1%. In the validation cohort, the sensitivity, specificity, PLR, and NLR were 75.0%, 66.9%, 2.26, and 0.37, respectively, with an NPV of 96.3%. The calibration curves for the scoring system in the derivation cohort (Fig. 4c) and the validation cohort (Fig. 4d) demonstrated strong agreement between predicted and observed probabilities, confirming the model’s stability and reliability.

Discussion

This study developed and validated a predictive model and simplified scoring system to assess the adequacy of bowel preparation for colonoscopy, integrating gut motility parameters and preparation regimens. Key predictors of inadequate bowel preparation included decreased (< 3 times/week) and increased (> 15 times/week) bowel movement frequency, stool consistency (Bristol Stool Scale), smaller PEG volumes, and intervals of ≥ 3 days since the last bowel movement before colonoscopy. The diagnostic nomogram demonstrated excellent calibration and discrimination, with robust performance across both the training and validation cohorts. The simplified scoring system derived from the nomogram provides a practical and clinically applicable tool, enabling personalized preparation strategies. These findings address the limitations of the empirical dosing strategy, offering an evidence-based framework to optimize preparation quality, enhance colonoscopy outcomes, and reduce the risk of procedure failures.

Our findings align with and expand upon prior research identifying critical factors influencing bowel preparation quality. Consistent with previous studies, we confirmed that constipation, characterized by reduced bowel movement frequency and hard stool consistency, is a significant predictor of inadequate preparation. Zhang Y et al.5 highlighted the association between low bowel motility and poor preparation quality, and our results further quantified this relationship by incorporating the Bristol Stool Scale into a predictive model. Additionally, consistent with Fuccio L et al.17, our results demonstrated that preparation quality significantly improved with increased PEG volume, showing the protective effects of 3 L and 4 L regimens. While previous studies have primarily focused on demographic and clinical risk factors, such as age and comorbidities, this study emphasizes the dynamic relationship between bowel motility and preparation quality. Our study had several novel findings. First, we identified a non-linear relationship between bowel movement frequency and preparation quality. While decreased bowel movement frequency is a well-established risk factor, we found that increased bowel movement frequency also exerts negative effects on bowel preparation. It may be due to intestinal dysmotility, which presents impaired coordination of bowel movement and ineffective excretion. Second, we stratified constipation severity, demonstrating that patients who had no bowel movements within two days before a colonoscopy showed a significantly higher likelihood of inadequate bowel preparation. In contrast, a colonoscopy shortly after a recent bowel movement substantially reduced this risk. Third, we incorporated the Bristol Stool Scale in our model, where it performed effectively as a continuous variable. Low stool water content, as seen with type 1 and type 2 stools, reduces the effectiveness of bowel preparation agents, as insufficient water prevents stool softening and complete evacuation. Hard stools also correlate with reduced gut motility, resulting in prolonged stool transit time, causing excessive water absorption in the colon and drier stools, which are more challenging to clear.

We developed a comprehensive diagnostic nomogram with exceptional calibration and discrimination, complemented by a simplified scoring system derived from the nomogram. This scoring system was constructed and validated, enabling clinicians to implement evidence-based, personalized preparation regimens easily. Moreover, the DCA demonstrated the clinical net benefit of our scoring system, offering a practical framework to guide preparation strategies. Importantly, external validation demonstrated its applicability across diverse populations, further validating the model’s robustness and reliability. Our scoring system achieved an AUC of 0.774 in external validation, surpassing most existing models, whose AUCs range from 0.621 to 0.7713,14,15,16,17,18,19. Notably, our system is streamlined and highly user-friendly, requiring patients to ask only four questions: bowel movement frequency, stool consistency, preparation regimen volume, and timing of the last bowel movement. This simplicity differentiates it from most existing models, which typically require at least five parameters17,19. For instance, Chen et al. developed a model with an AUC of 0.80, significantly improving over previous models12. However, their study exclusively included patients using a 4 L split-dose PEG regimen, limiting its generalizability to real-world scenarios where 2–3 L regimens are more common. Our scoring system is simple, efficient, and broadly applicable, bridging the gap between theoretical predictors and practical implementation.

Besides a well-performed scoring system, this study provides numerous valuable insights that warrant further exploration. First, improving motility has the potential to be an effective strategy for enhancing bowel cleansing, especially in patients with slow-transit constipation. Second, optimizing the timing of colonoscopy relative to bowel movements may significantly improve outcomes. Scheduling a colonoscopy within two days of a spontaneous bowel movement could improve preparation adequacy. When a colonoscopy is already scheduled, it could work that using adjunctive measures such as laxatives to induce bowel movements or increasing the dose of PEG given if no bowel movements within two days before colonoscopy. Integrating such timing strategies into clinical practice, especially for constipated patients, represents a simple yet impactful approach to optimizing bowel preparation and improving the overall success of colonoscopy. Water-assisted colonoscopy techniques such as water exchange may enhance bowel cleanliness in select patients. Future studies are warranted to evaluate whether such techniques may improve preparation adequacy in high-risk patients.

Although all colonoscopies in this study were performed using standard intra-procedural cleaning maneuvers—including water flushing, irrigation, and suctioning—water-assisted colonoscopy techniques such as water immersion and water exchange were not employed. These methods have been reported to enhance mucosal visualization, particularly in patients with residual debris or suboptimal preparation22. While our observed bowel preparation adequacy rate of approximately 90% suggests the effectiveness of conventional cleaning approaches, it remains possible that a subset of patients may have achieved improved BBPS scores with water-assisted techniques. We acknowledge this as a methodological limitation. Future prospective studies incorporating water-assisted techniques may be warranted to determine their additional value in improving bowel cleanliness, especially among patients identified as high-risk by predictive models.

Despite the strengths of this study, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the data collection relied on self-reported information regarding bowel habits and stool consistency, which may have introduced recall bias or subjective variability. Second, while our scoring system was validated in an external cohort, the validation sample size was relatively small and derived from a single medical center, potentially limiting its generalizability. To address these limitations, future research should focus on expanding the external validation cohort to include larger and more diverse populations, ensuring broader applicability of the predictive model. Incorporating objective measures of bowel habits, such as motility tests or electronic stool diaries, could reduce the reliance on subjective, self-reported data and enhance the accuracy of predictions. These advancements would improve bowel preparation models’ predictive accuracy and clinical utility, ultimately enhancing colonoscopy outcomes and patient care.

In conclusion, this study developed a predictive model and simplified scoring system that enhanced the precision and practicality of bowel preparation for colonoscopy. The model offers a significant step toward individualized care in gastrointestinal diagnostics by focusing on patient-specific factors, such as gut motility and preparation regimens. Its external validation underscores its reliability and potential for application across various clinical settings. The system can be pivotal in optimizing colonoscopy effectiveness, enhancing patient care, and reducing the burden of repeat procedures.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are not openly available due to reasons of sensitivity and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Hassan, C. et al. Bowel preparation for colonoscopy: European Society of Gastrointestinal endoscopy (ESGE) guideline - update 2019. Endoscopy 51(8), 775–794. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-0959-0505 (2019).

Corley, D. A. et al. Adenoma detection rate and risk of colorectal cancer and death. N Engl. J. Med. 370(14), 1298–1306. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1309086 (2014).

Chokshi, R. V., Hovis, C. E., Hollander, T., Early, D. S. & Wang, J. S. Prevalence of missed adenomas in patients with inadequate bowel preparation on screening colonoscopy. Gastrointest. Endosc. 75(6), 1197–1203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gie.2012.01.005 (2012).

Pantaleón Sánchez, M. et al. Prevalence of missed lesions in patients with inadequate bowel preparation through a very early repeat colonoscopy. Dig. Endosc. 34(6), 1176–1184. https://doi.org/10.1111/den.14278 (2022).

Zhang, Y. et al. Predictors of inadequate bowel preparation in older patients undergoing colonoscopy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 149, 104631. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2023.104631 (2024).

Fostier, R. et al. Models and scores to predict the adequacy of bowel preparation before colonoscopy. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 67, 101859. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpg.2023.101859 (2023).

Feng, L. et al. Risk factors for inadequate bowel preparation before colonoscopy: A meta-analysis. J. Evid. Based Med. 17(2), 341–350. https://doi.org/10.1111/jebm.12607 (2024).

Beran, A. et al. Risk factors for inadequate bowel preparation in colonoscopy: A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 3 https://doi.org/10.14309/ajg.0000000000003073 (2024).

Mahmood, S., Farooqui, S. M. & Madhoun, M. F. Predictors of inadequate bowel preparation for colonoscopy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 30(8), 819–826. https://doi.org/10.1097/MEG.0000000000001175 (2018).

Yao, R. et al. Effect of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists on bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 119(6), 1154–1157. https://doi.org/10.14309/ajg.0000000000002564 (2024).

Amatya, B., Elmalik, A., Lowe, M. & Khan, F. Evaluation of the structured bowel management program in inpatient rehabilitation: a prospective study. Disabil. Rehabil. 38(6), 544–551. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2015.1047970 (2016).

Chen, L. et al. The superiority of a preparation-related model for predicting inadequate bowel preparation in patients undergoing colonoscopy: A multicenter prospective study. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 37(12), 2297–2305. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgh.16010 (2022).

Gkolfakis, P. et al. Comparative performance and external validation of three different scores in predicting inadequate bowel preparation among Greek inpatients undergoing colonoscopy. Ann. Gastroenterol. 36(1), 25–31. https://doi.org/10.20524/aog.2023.0757 (2023).

Hassan, C. et al. A predictive model identifies patients most likely to have inadequate bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 10(5), 501–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2011.12.037 (2012).

Dik, V. K. et al. Predicting inadequate bowel preparation for colonoscopy in participants receiving split-dose bowel preparation: development and validation of a prediction score. Gastrointest. Endosc. 81(3), 665–672. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gie.2014.09.066 (2015).

Gimeno-García, A. Z. et al. Risk factors for inadequate bowel preparation: a validated predictive score. Endoscopy 49(6), 536–543. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0043-101683 (2017).

Fuccio, L. et al. Factors that affect adequacy of colon cleansing for colonoscopy in hospitalized patients. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 19(2), 339–348e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2020.02.055 (2021).

Berger, A. et al. A predictive score of inadequate bowel preparation based on a self-administered questionnaire: PREPA-CO. Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 45(4), 101693. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinre.2021.101693 (2021).

Okamoto, N. et al. Predicting inadequate bowel preparation when using sodium picosulfate plus magnesium citrate for colonoscopy: development and validation of a prediction score. Digestion 103(6), 462–469. https://doi.org/10.1159/000527312 (2022).

Riley, R. D. et al. Calculating the sample size required for developing a clinical prediction model. BMJ 368, m441. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m441 (2020). Published 2020 Mar 18.

Lai, E. J., Calderwood, A. H., Doros, G., Fix, O. K. & Jacobson, B. C. The Boston bowel preparation scale: a valid and reliable instrument for colonoscopy-oriented research. Gastrointest. Endosc. 69(3 Pt 2), 620–625. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gie.2008.05.057 (2009).

Cadoni, S. et al. Water-assisted colonoscopy: an international modified Delphi review on definitions and practice recommendations. Gastrointest. Endosc. 93(6), 1411–1420e18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gie.2020.10.011 (2021).

Funding

The work received funding from (1) Nanjing Medical Key Technology Development Project (ZKX22018), (2) Jiangsu Provincial Health Commission Medical Research General Project (H2023138), (3) fundings for Clinical Trails from the Affiliated Drum Tower Hospital, Medical School of Nanjing University (2023-LCYJ-MS-07).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design: N. Z., J. L., and B. X.Collection of the data: J. L., H. W., R. W., Y. Z., X. L., and W. Z.Analysis and interpretation of the data: R. W., H. W., B. X., and N. Z.Drafting of the article: R. W. and H. W.Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content: N. Z., B. X., J. L., R. W., H. W., Y. Z., X. L., Y. Z., and W. Z.Final approval of the article: all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics statement

The study was conducted following the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013) and approved by the ethics committees of Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital and Northern Jiangsu People’s Hospital (Approval No. 2024-820-01), which was registered on the Clinical Trials website (ChiCTR2400094160). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before enrollment. The study followed the guidance of the Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis Or Diagnosis (TRIPOD) statement.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, H., Wu, R., Zhang, Y. et al. Development and validation of a gut motility based model for predicting bowel preparation quality. Sci Rep 15, 28265 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13739-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13739-0