Abstract

Alpine peatlands on the eastern Tibetan Plateau are vital carbon sinks, with soil moisture playing a key role in peatland carbon cycling. However, they face disruptions in their carbon balance due to drought, which reduces soil water content. Therefore, this study investigated microbially driven water-carbon interactions through field surveys, laboratory incubations, and metagenomics. Soil drying contributes to changes in both the metabolic quotient (qCO2) and the microbial quotient (Cmic: Corg), as well as the microbial abundance. As the soil water content decreased, both qCO2 and Cmic: Corg exhibited an overall increasing trend. Moreover, soil water content had a more significant effect on soil bacteria, while its effect on fungi and archaea was minimal. Soil microbial carbon decomposition genes were also influenced by changes in soil water content. Next, we used RDA to analyze the relationship between soil respiration quotient values and microbial traits. The results revealed that Actinobacteria were strongly negatively correlated with qCO2, whereas Archaea and Candidatus_R were positively correlated with qCO2. Additionally, Cmic: Corg was closely linked to fungi, and both Proteobacteria and Acidobacteria exhibited positive correlations. qCO2 had a strong negative correlation with genes involved in the degradation of monosaccharides and hemicellulose, whereas Cmic: Corg was positively correlated with genes related to the degradation of cellulose and lignin. Moreover, droughts affected microbial residue carbon and associated carbon metabolic pathways. Therefore, changes in soil water content may be an important factor influencing carbon metabolism processes in peatlands. This study deepens our understanding of the effects of drought on soil metabolism and microbial dynamics in alpine peatlands and provides new insights into the microecological mechanisms of soil carbon cycling in these ecosystems in the context of global change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Global Peatland Assessment Report, published in 2022, indicates that the total area of peatlands worldwide is approximately 4.88 million km21. It is estimated that they store 500–700 Gt (1 Gt = 103 Mt) of soil carbon, contributing 21–47% of the global soil carbon storage (1500–2400 Gt C)2,3. Therefore, peatlands are considered vital long-term carbon sinks in support of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal on climate change4. However, peatlands worldwide have been significantly impacted by climatic drying over the past century. Drought and a decline in the water table have led to considerable reductions in peatland areas5,6. These changes can shift the anaerobic conditions of wetland soils and sediments to aerobic ones, potentially halting peat formation and converting carbon sequestration processes into carbon mineralization. This, in turn, could accelerate global warming7. Soil respiration (SR) is a key pathway in soil carbon turnover and is widely recognized as the carbon cycle process that follows gross primary productivity (GPP)8,9. However, global warming is expected to accelerate the release of soil carbon dioxide (CO2) into the atmosphere via soil respiration, creating strong positive feedback with climate change10. In addition, some studies have shown that due to the unique ecological and hydrological characteristics of peatlands, soil respiration in peatlands is influenced mainly by soil moisture, i.e., the soil water content11,12. Moreover, soil microorganisms play an important role in soil respiration13,14. However, drought or changes in moisture are usually key factors affecting microbial composition and activity15. They cause soil microorganisms in peatlands to shift from anaerobic to aerobic conditions and induce changes in the carbon function of the microbial community, with these changes being more sensitive in alpine regions16.

In general, soil microbial activity and biomass are critical determinants of respiration rates17with the relationship between respiration and biomass expressed as the microbial metabolic quotient (qCO2)18. Given that a higher qCO2 indicates a greater release of CO2 per unit of microbial biomass carbon (MBC), this quotient serves as a key parameter for assessing soil carbon storage19. Globally, qCO2 is influenced by environmental factors such as climate and soil characteristics20. Specifically, soil pH, temperature, and inorganic phosphorus availability positively impact qCO2, whereas soil organic carbon density and microbial nitrogen: phosphorus and carbon: phosphorus ratios have negative effects across large spatial scales21,22. Soil moisture also plays a role; in the Inner Mongolian grasslands, qCO2 is negatively correlated with precipitation23. Several researchers have reported that short-term reductions in precipitation significantly decrease qCO2 in the top 10 cm of soil24. Conversely, in subtropical Chinese fir (Cunninghamia lanceolata) plantations, qCO2 was significantly and positively correlated with the soil water content25. Biologically, qCO2 is influenced by the microbial community structure26 and is positively correlated with bacterial richness but negatively related to fungal richness across forest biomes27. Thus, theoretically, any factor that alters the physical or chemical properties of soil may influence the quantity and activity of soil microorganisms, which in turn could affect qCO223,26. For example, low soil moisture content restricts microbial metabolic activity and the diffusion of respiratory substrates, weakening soil respiration, whereas high moisture content can limit oxygen diffusion, thereby affecting microbial respiration28. Furthermore, moisture can influence microbial residual carbon by altering microbial biomass and activity29,30. Microbial residue carbon (MRC) is a significant component of soil carbon31. Some studies indicate that higher metabolic efficiency (i.e., a lower metabolic quotient and higher C use efficiency) can lead to increased microbial biomass, potentially increasing soil organic carbon (SOC) sequestration through microbial residue carbon accumulation32. Thus, microorganisms play a critical role in soil carbon production and metabolism. In contrast to microbial taxonomic data, functional genes can significantly influence carbon processes in soils by enabling the ecological functions associated with the enzymes they encode33. These changes in labile and stable carbon are largely associated with the abundance of functional genes related to decomposition34. Furthermore, various soil factors, including soil water content and vegetation characteristics, collectively regulate the abundance of these functional microbial genes35.

The peatlands on the eastern edge of the Tibetan Plateau represent a typical alpine peatland in Asia and are the largest such concentration in China. Previous studies on soil carbon processes in peatlands have focused primarily on the effects of general environmental factors36such as temperature and soil water content, as well as microbial community structure33on soil carbon processes (e.g., soil respiration). However, amidst global climate change, the impact of microbial functional genes on qCO2 and the contribution of MRC to alpine peatland SOC remain inadequately understood. However, understanding how different microbial functional genes influence soil carbon stocks is vital for predicting the future of carbon sequestration in a changing climate.

To this end, we investigated, sampled, and measured surface soils and analyzed microbial characteristics through metagenomic sequencing in alpine peatlands on the eastern Tibetan Plateau, which exhibit varying hydrological conditions. Our primary hypotheses are as follows: (1) The carbon content of microbial residues in alpine peatlands is significantly influenced by changes in soil water content. (2) The quotient values (metabolic quotient and microbial quotient) of soil respiration in alpine peatlands are regulated by moisture-mediated microbial characteristics. Addressing these questions within the context of global climate change will enhance our understanding of the microecological mechanisms governing soil metabolism and carbon cycling in peatlands.

Materials and methods

Study area

The study area, which is situated on the eastern edge of the Tibetan Plateau (32.73°~32.39°N, 102.34°~102.41°E) (Fig. 1), experiences a cold-temperate monsoon continental plateau climate. It has an average altitude of 3507 m and an annual temperature of 1.4 °C and receives 860.8 mm of rainfall per year. The region has a brief growing season (July-September) and a long, cold nongrowing season. It is covered mainly by grassland with an average vegetation height of 30 cm, and the predominant species include Carex alatauensis, Elymus nutans, Carex tristachya, Elymus dahuricus and Poa pachyantha.

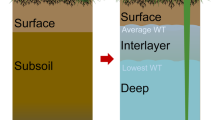

Soil collection

This study selected 12 sample sites through remote sensing image interpretation and field surveys, combined them with the water conditions of the study area in recent years and corrected them by measuring the soil water content. Based on differences in soil water content, the sample sites were divided into three categories: water-rich wetland (WR), water-scarce wetland (WS), and dry wetland (D) (Table S1). For each site, a 50 m×50 m plot was set up for soil sampling, with 10 random points within each plot. Visible plants and litter were removed before sampling, and the top 10 cm of soil was mixed. Sampling avoided deep-water areas, and shallow areas were drained first. Ten samples were combined into composite samples, from which large plant debris and fine roots were removed. These composite samples were then divided for analyses of soil properties, soil respiration (50 g fresh weight), and microbial residues and stored at −40 °C for future metagenomic sequencing.

Measurement of soil respiration

Prior to the measurement of soil respiration, the soil samples underwent a preincubation period of 7 days at a temperature of 20 °C in the absence of light, and their weight was measured daily to adjust the water content to 60%. At the end of the preincubation, the soil samples were incubated for another day, soil respiration was then quantified using the static alkali absorption method (Fig. S1), and the amount of CO2 absorbed was calculated from the amount of HCl consumed by titration.

Where C represents the actual concentration of HCl configured (mol L−1); m represents the mass of anhydrous Na2CO3 (g); V1 represents the amount of HCl used for titration of Na2CO3 (ml); V0 represents the amount of HCl used for titration of the blank (ml); 52.99 represents the molar mass of ½ Na2CO3 (g mol−1); and 250/25 represents the multiplier of the fraction.

Where W is the weight of CO2 in 250 ml of solution (g); V1 is two times the number of millilitres of HCl used in the test solution with methyl orange as the indicator (ml); V2 is two times the number of millilitres of HCl used in the blank test solution with methyl orange as the indicator (ml); C means the molar concentration of HCl (mol L−1); 44/2 × 1000 is the millimolar mass of CO2; and 250/25 indicates the multiplicity of the fractions.

Where Cum represents cumulative soil respiration (mg C-CO2 g−1); Ct represents the carbon content (mg C-CO2 L−1) in different treatments; Cb represents the carbon content in the blank lye (mg C-CO2 L−1); V denotes the volume of lye (mL); and W represents soil weight (g).

Where BR is the carbon emitted by soil respiration per hour.

Calculation of microbial metabolic coefficients

The soil qCO2 was calculated as the ratio of microbial respiration to microbial biomass18. Microbial biomass C (MBC) was determined by the fumigation extraction method37. Subsamples of sieved soil were fumigated with ethanol-free CHCl3 for 24 h and then extracted with 0.5 M K2SO4 solution. The amount of MBC could be calculated from the amount of FeSO4 consumed by titration.

Where ω(C) is the mass fraction of organic carbon (Oc) (mg kg−1); V0 is the volume of FeSO4 consumed in titrating the blank sample (ml); V1 is the volume of FeSO4 consumed in titrating the sample (ml); c is the concentration of FeSO4 solution (mol L−1); c is the concentration of FeSO4 solution (mol L−1); 3 is the millimolar amount of carbon (1/4 C), M (1/4 C) = 3 (mg mmol−1); 1000 is a conversion coefficient to kg; ts is the dilution factor; m is the mass of dried soil (kg).

Where ω(C) is microbial biomass carbon (Bc) mass fraction (mg kg−1); Ec is the difference between the organic carbon of fumigated and unfumigated soil samples (mg kg−1); KEC is the proportion of carbon (C) in the microbes killed by chloroform fumigation that is extracted by leaching, generally taken as 0.45.

The metabolic quotient (qCO₂) was calculated as the ratio of soil BR to MBC (BR/MBC), and the microbial quotient (Cmic: Corg) was calculated as the ratio of microbial biomass C to soil organic carbon38.

Determination of the carbon content of microbial residues

The Zhang and Amelung method was used to determine the soil aminosugars39. Finally, the contents of fungal and bacterial residual carbon were calculated based on the contents of GluN and MurA in the soil samples.

where 179.17 and 251.23 are the molecular weights of GluN and MurA, respectively; 9 and 45 are conversion factors. The total MRC was estimated as the sum of fungal MRC and bacterial MRC.

Analysis of soil properties

The soil pH was measured using a pH monitor (Thermo Orion-868, MA, USA). Total nitrogen (TN) was quantified using the Kjeldahl method, which involves the use of concentrated sulfuric acid and a mixed catalyst decoction. Dissolved organic carbon (DOC) was extracted using a MK2SO4 solution and analyzed using a TOC-TN analyzer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan)40. The total carbon (TC) and soil organic carbon (SOC) contents were determined using the external heating method with K2Cr2O741. Dissolved organic nitrogen (DON) was calculated as the difference between soil soluble total nitrogen and soil inorganic nitrogen. The carbon-to-nitrogen ratio (C/N) was calculated as the ratio of SOC to TN. The soil texture, including that of the sand, silt, and clay, was determined using the hydrometer (TM-85) method42.

DNA extraction and sequencing

Total genomic DNA was extracted from the community using the E.Z.N.A.Soil DNA Kit (Omega, M5635-02, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. DNA concentration was measured with a Qubit 4.0 (Thermo, USA) to ensure adequate high-quality genomic DNA.

For each sample, 500 ng of DNA was used for library preparation. Libraries were constructed with the Hieff NGS® MaxUp II DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina® (12200ES96, YEASEN, China) according to the manufacturer’s guidelines, incorporating index codes for sample identification. DNA was fragmented into approximately 500 bp pieces using Covaris 220. These fragments were purified with Hieff NGS™ DNA Selection Beads (12601ES56, YEASEN, China). After purification, the DNA underwent end repair, adapter ligation, and fragment selection. PCR was then performed with 2×Super Canace®II High-Fidelity Mix, Primer Mix (p5/p7), and Adaptor Ligated DNA. The PCR products were purified with Hieff NGS™ DNA Selection Beads and assessed for quality using a Qubit®4.0 Fluorometer. Libraries were quantified, pooled, and sequenced using NovaSeq 6000 (Illumina, USA).

Sequencing data quality was assessed with Fastp (version 0.36). The raw reads were filtered by removing adaptor sequences, eliminating low-quality bases (Q < 20) from the 3’ to 5’ ends, applying a sliding window approach to discard bases less than 20 from the read tails (4 bp window), correcting overlaps and inconsistent bases between read pairs, and discarding reads shorter than 35 nt along with their pairs. The clean data was then used for further analysis.

Metagenome assembly and Binning

Initially, Megahit (v1.2.9) was used for multi-sample mixed splicing to generate preliminary spliced contig sequences. Bowtie2 (v2.1.0) then mapped cleaned reads to these spliced results, extracted unmapped reads, and used SPAdes (v3.13) for re-splicing to obtain low-abundance contigs. MetaWRAP (v1.3.2) performed binning processes including sorting, purification, quantification, reassembly, and identification to produce a high-integrity, low-contamination draft genome of a single bacterium. To predict open reading frames (ORFs), Prodigal (v2.60) identified genes ≥ 100 base pairs and translated them into amino acids. CD-HIT (v2.60) was used to remove redundancies, creating a non-redundant gene set. Salmon (v1.5.0) then constructed a specific index for this gene set, employing a dual-phase algorithm and bias model to quantify gene abundance based on gene length. The gene abundance calculation formula is as follows:

Where Gk is the gene abundance; r is the number of reads of the gene on the ratio; and L is the length of the gene.

Screening, classification and annotation of carbon decomposition genes

The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) is an extensive database covering biological systems, including genomes, chemicals, and their functions43. KEGG GENES, one of its components, contains protein sequences from all known complete genomes and offers fundamental gene information. Using DIAMOND (version 0.8.20) to compare genomic protein sequences with the KEGG database—applying filters like E-value < 1e-5 and score > 60—we identified KO numbers related to carbon degradation genes. Linking these KOs to specific pathways and modules provided annotation for the gene sequences, allowing us to retrieve genes with similar functions for further study. Building on previous research44labile carbon compounds were classified into monosaccharides, disaccharides, polysaccharides, hemicelluloses, cellulose, and aminosugars, whereas stable carbon compounds included lipids, chitin, and lignin (the basic information on the carbon decomposition functional genes detected in this study is shown in Table S3). The analysis involved counting gene sequences associated with various microbial functions.

Statistical and analytical methods

All the data were tested for a normal distribution. One-way analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA) was used to assess the variation in the soil properties and microbial metabolic coefficients under different water conditions. For significant main effects (p < 0.05), Tukey’s honestly significant difference (Tukey’s HSD) post hoc test was applied for multiple comparisons among treatment groups. Nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) was used to analyze the variability among the sample plots with different soil water contents. Mental tests were used to test the effects of soil water content and related environmental factors on key indicators. Redundancy analysis (RDA) was used to analyze microbial communities and their associated functional genes in relation to key indicators. The data were processed and analyzed using Microsoft Excel 2019 and SPSS 22 (IBM, USA) and plotted using Origin 2021. The map, shown as Fig. 1, was created using ArcGIS 10.2 (https://desktop.arcgis.com/en/desktop/index.html).

Results

Effects of drought on the MRC, metabolic quotient and microbial quotient in peatlands

Both the qCO2 and Cmic: Corg values of the soils differed under the influence of drought (Fig. 2). The qCO2 differed significantly between WR and WS but not among WR, WS, and D. However, the mean qCO2 values were ordered as WS > D > WR. The Cmic: Corg of the soils was significantly lower in WR and WS than in D. Furthermore, droughts affected microbial residue dynamics in peatland ecosystems (Fig. 2). The bacterial MRC, fungal MRC and total MRC were generally higher in water-rich wetlands than in water-scarce and dry wetlands (Fig. S2).

Differences between qCO₂, Cmic: Corg and MRC under different moisture conditions. qCO₂ refers to the metabolic quotient, Cmic: Corg refers to the microbial quotient, MRC refers to microbial residue carbon. WR is water-rich wetlands, WS is water-scarce wetlands, D is dry wetlands. Different letters indicate the significance level (p < 0.05).

Soil water also influenced the soil carbon content, with peat soils generally having higher carbon contents under water-rich conditions and lower carbon contents under dry conditions (Table S2). MRC was closely linked to soil carbon (TC, SOC and C/N), with a positive connection; qCO₂ and Cmic: Corg were negatively correlated with soil carbon, whereas Cmic: Corg was significantly related to soil carbon and qCO₂ was significantly related to MRC (Fig. 3a). In addition, the soil water conditions regulated the dynamics of qCO₂, Cmic: Corg and MRC (Fig. 3b).

Soil microorganisms in peatlands as affected by soil drought

Among the microorganisms found in peatland ecosystems, soil fungi are the most prevalent and are dominated primarily by Ascomycota, followed by bacteria (Fig. 4). Among the bacterial phyla, Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria had the highest relative abundances. The functional genes involved in the degradation of monosaccharides were the most abundant across all phyla, followed by genes for lignin, lipids, disaccharides, polysaccharides, cellulose, and hemicellulose; the functional genes involved in the degradation of amino sugars were the least abundant (Fig. 4).

The microbial content within these environments is influenced by the level of soil water content (Fig. S3). Overall, the effect of water conditions on soil bacteria was more significant, whereas its impact on fungi and archaea was not significant. Among the bacterial phyla, Acidobacteria, Gemmatimonadetes, Chloroflexi, and Candidatus_R had significant effects on changes in soil water content, whereas moisture had a weak effect on Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria (Fig. 5).

Moreover, various functional genes involved in carbon decomposition in soil microorganisms are affected by changes in soil water content (Fig. 6).

Water-mediated soil microbes influence soil metabolic processes in peatlands

We also analyzed the effects of soil microbial traits on qCO₂ and Cmic: Corg using redundancy analysis (RDA) (Fig. 7). The results indicated that Archaea, Candidatus_R, and Actinobacteria presented significant relationships with qCO₂, with Actinobacteria showing a strong negative correlation, whereas Archaea and Candidatus_R presented positive correlations. Additionally, a strong correlation was observed between Cmic: Corg and most microorganisms. Notably, Cmic: Corg was strongly correlated with fungi, and both Proteobacteria and Acidobacteria presented strong positive correlations. Moreover, MBC was strongly positively correlated with Gemmatimonadetes, fungi, and Chloroflexi, and in general, MBC was positively correlated with bacteria overall. Furthermore, carbon decomposing functional genes were linked to soil microbial metabolism and residual carbon. qCO₂ was strongly negatively correlated with functional genes involved in the degradation of monosaccharides and hemicellulose. In contrast, Cmic: Corg was strongly positively correlated with functional genes associated with the degradation of cellulose and lignin. Moreover, MBC was strongly negatively correlated with genes involved in the degradation of polysaccharides and lipids, while it was positively correlated with genes related to the degradation of cellulose and lignin.

The effects are driven primarily by specific genes and pathways. The genes involved included fabB, glgB, glgA, rpiB, pgi-pmi, rhaT, pgm, GMPP, glk, K16881, and TPI. The associated pathways encompass ABC transporters, fatty acid metabolism, amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism, starch and sucrose metabolism, and glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, among others. Additionally, all of these genes and pathways are influenced by changes in water conditions to varying degrees (Fig. 8).

Discussion

First, drought causes changes in the microbial metabolic quotient (qCO2) of peatlands. As the soil water content decreases, qCO2 tends to increase overall (Fig. 2). He et al.45 also produced similar results to ours in the wetlands. The water content often alters the microbial community structure and inhibits microbial activity, leading to a reduction in microbial biomass carbon (MBC)46. As the soil moisture content decreases, soil aeration improves, allowing oxygen to diffuse more freely and increasing oxygen utilization efficiency47. On the other hand, when the soil moisture content is too high, oxygen diffusion is restricted28. Therefore, both excessive and insufficient moisture can inhibit soil respiration. Only when soil moisture is within an optimal range can soil respiration be effectively promoted48. Therefore, changes in soil moisture affect the soil metabolic quotient. Our results show that a lower qCO2 is linked to a higher organic carbon content in the soil (Fig. 2, Table S2). This finding aligns with the generally negative relationship between qCO2 and microbial carbon use efficiency (CUE)49. Specifically, a higher CUE supports more efficient biosynthesis by soil microorganisms, which in turn enables the soil to store more organic carbon14. Droughts also significantly affected the soil organic carbon content, which led to a significant effect of soil water content on Cmic: Corg (Fig. 2). Thus, our results suggest that drought increases qCO2 and Cmic: Corg in alpine peatlands, which may be detrimental to SOC sequestration because a higher qCO2 is accompanied by more rapid SOC decomposition and C loss27.

We found significant effects of droughts on microbial residues in peatlands (Fig. 2). The overall trend of increasing soil moisture promoting the accumulation of microbial residues was consistent with the results of other researchers29. This may be because moisture affects microbial growth and metabolic processes and activity, which in turn affects microbial abundance and residue formation29. Fungal MRC was higher than bacterial MRC in peatlands (Fig. S2), possibly because fungi are more tolerant to water stress50. This finding is also consistent with the results of other researchers51. Similar to our findings (Fig. 3a), the cellular residues of fungi and bacteria are important components of the soil’s stable organic carbon pool52,53. Changes in the microbial metabolic quotient reflect the microbial utilization of soil organic carbon54. This process may be influenced by the soil water content content (Fig. 3b).

In addition, peatland soil drying has an effect on microorganisms (Fig. 5 and Fig. S3). This may be because fungi usually contain mycelia and can compensate for physiological stresses caused by water stress by redistributing the use of mycelial water and mycelial growth within soil pores to obtain nutrients55; therefore, peatlands are more abundant in fungi than bacteria. Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria are tolerant to changes in moisture conditions55leading to the highest relative abundance among bacterial phyla. Among the bacterial phyla, Acidobacteria, Gemmatimonadetes, Chloroflexi, and Candidatus_R had significant effects on changes in soil water condition (Fig. 5). Similar results have been reported in peatlands in previous studies56. Additionally, soil microbial carbon decomposition genes are affected by changes in soil water content (Fig. 6), which is consistent with the findings of Liu57. This may be because moisture regulates microbial function by affecting soil substrate availability and quality58. This pattern is observed in alpine wetlands and other ecosystems, suggesting that drought stress affects the abundance and functional composition of soil microorganisms59. Moreover, variations in soil moisture levels impact the biochemical processes of microorganisms, resulting in alterations in both the activity and composition of the soil microbial community60. Our study revealed the highest abundance of microbial functional genes associated with monosaccharide degradation, which aligns with findings from other regions, including forests44 and permafrost areas46suggesting that genes involved in the degradation of monosaccharides occupy important positions in different environments. Due to the accumulation of lignin as a result of the special hydrothermal conditions in peatlands, coupled with the difficulty of degrading lignin itself61the content of functional genes involved in the degradation of lignin is also relatively high in these environments. This phenomenon also occurs in forest ecosystems44.

Some studies have shown that water content affects soil respiration by influencing the microbial diversity and functional microorganisms involved in soil carbon decomposition36. Research has also shown that soil microbial structure and activity can influence qCO223. Our findings revealed that Archaea, Candidatus_R, and Actinobacteria were significantly related to qCO2 (Fig. 7). Bacterial communities are better able to metabolize soil carbon due to the stability and metabolic capacity of the dominant bacteria62. Actinomycetes play crucial roles in peatland soil metabolism as key decomposers, breaking down complex organic matter, surviving in extreme environments, and supporting local biogeochemical cycles63. Additionally, a strong correlation was observed between MRC and Cmic: Corg, as well as with most microorganisms. Because microorganisms not only play crucial roles in the decomposition of soil organic matter and carbon metabolism but also accumulate in the soil as microbial residues after they die52. Acidobacteria and Proteobacteria are among the most abundant phyla in terrestrial soils64,65. Our results also highlight the importance of these two bacterial phyla in determining the soil microbial quotient (Fig. 7). Emerging evidence suggests that the abundance of functional genes may serve as an indicator of enzymatic activity potential, thereby influencing the subsequent mineralization of soil organic carbon66,67. Additionally, our results revealed that carbon decomposition-related functional genes were strongly associated with both microbial metabolic activity and the accumulation of microbial residual carbon (Fig. 7), highlighting their dual role in driving carbon turnover and stabilization processes.

qCO2 was strongly correlated with functional genes involved in the degradation of monosaccharides. This phenomenon, where genes involved in monosaccharide degradation influence soil carbon processes, has also been observed in other ecosystems68. Monosaccharides are the most important biomarkers in terms of quantity, and their levels are strongly positively correlated with microbial biomass69. Therefore, the decomposition of monosaccharides affects the metabolism of soil microorganisms70. Because monosaccharides are typically the primary drivers of microbial activity in the soil, other carbon sources, such as cellulose, must first be broken down into monosaccharides by specific enzymes before they can be utilized by microorganisms71,72. The microbial quotient (Cmic: Corg), which reflects the proportion of active organic carbon and the availability of the total soil carbon pool73is strongly positively correlated with functional genes involved in the degradation of cellulose and lignin (Fig. 7). Due to the unique hydrothermal conditions of peatlands, plant-derived carbon is not easily decomposed and tends to accumulate, leading to an increase in the organic carbon content of peatlands74,75. These results suggest that microorganisms containing functional genes that degrade lignin and cellulose regulate soil carbon availability, whereas those with functional genes for degrading monosaccharides influence soil carbon use efficiency. Finally, we also identified specific carbon catabolic genes and metabolic pathways that are influenced to varying degrees by the soil water content and impact soil carbon metabolism and processes (Fig. 8). GMPP is thought to be the gene that edits GDP-mannose pyrophosphorylase, which is essential for the normal survival of organisms76and its abundance may affect soil carbon production and metabolism. glgB, which is significantly associated with Cmic: Corg, plays important roles in growth processes such as glycogen synthesis77. Pathways such as ABC transporters are influenced to varying degrees by changes in soil water content (Fig. 8), as observed in other studies78.

Overall, we have provided a new perspective on soil carbon cycling in alpine peatlands on the eastern Tibetan Plateau. However, there are still several limitations that need to be discussed. First, indoor incubation experiments do not correspond exactly to actual soil conditions, so long-term observations in the field need to be strengthened. Second, the metabolic quotient is usually calculated from soil heterotrophic respiration (i.e., microbial respiration); however, current soil respiration measurements also include autotrophic respiration as well as respiration from plant debris that cannot be completely removed; therefore, new research methods are needed in the future to improve the accuracy of the measurements. Third, the enzymes encoded by the functional genes play a key role in the carbon degradation process, which we did not emphasize. We will further clarify this in a follow-up study.

Conclusions

This study examined the impact of drought on microbial metabolism quotient values. These results indicate that drought may increase the soil metabolic quotient and accelerate carbon loss while also affecting soil microorganisms, whose traits play crucial roles in carbon metabolism. We identified key functional genes and microbial phyla that significantly influence the qCO2 and Cmic: Corg. Specifically, microbial functional genes related to monosaccharides play a key role in influencing the qCO2, whereas genes responsible for degrading plant-based sources (cellulose and lignin) affect the Cmic: Corg. Additionally, drought also impacts the content of microbial residues in peatlands. In conclusion, soil water content may be an key factor affecting carbon metabolism processes in peatlands. Improving moisture conditions through water management and rewetting may help reduce qCO2, increase microbial carbon utilization efficiency, increase microbial residue accumulation in peatlands, and ultimately increase the carbon sink capacity of alpine peatlands, strengthening their ability to mitigate climate change.

Data availability

The bacterial and fungal DNA sequences produced in this study can be accessed from the GenBank database at the National Center for Biotechnology Information, using the project accession numbers PRJNA987568 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/?term=PRJNA987568). Other data will be available upon request from the corresponding author at kangyuyao@foxmail.com.

References

UNEP, Global Peatlands Assessment. The State of the World’s Peatlands: Evidence for Action Toward the Conservation, Restoration, and Sustainable Management of Peatlands (United Nations Environment Programme, 2022).

Page, S. E. & Baird, A. J. Peatlands and global change: response and resilience. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 41, 35–57 (2016).

Friedlingstein, P. et al. Global carbon budget 2020. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 12(4), 3269–3340 (2020).

Huang, Y. Y. et al. Trade off of CO2 and CH4 emissions from global peatlands under water-table drawdown. Nat. Clim. Change. 11 (7), 618–622 (2021).

Evans, C. D. et al. Overriding water table control on managed peatland greenhouse gas emissions. Nature 593 (7860), 548–552 (2021).

Leifeld, J. & Menichetti, L. The underappreciated potential of peatlands in global climate change mitigation strategies. Nat. Commun. 9, 1071 (2018).

Ma, L. et al. A globally robust relationship between water table decline, subsidence rate, and carbon release from peatlands. Commun. Earth Environ. 3 (1), 254 (2022).

Davidson, E. A., Janssens, I. A. & Luo, Y. On the variability of respiration in terrestrial ecosystems: moving beyond Q10. Glob. Change Biol. 12 (2), 154–164 (2006).

Lei, J. et al. Temporal changes in global soil respiration since 1987. Nat. Commun. 12 (1), 403 (2021).

Wang, M. M. et al. Global soil profiles indicate depth-dependent soil carbon losses under a warmer climate. Nat. Commun. 13(1), 5514 (2022).

Dadap, N. C. et al. Drainage canals in Southeast Asian peatlands increase carbon emissions. Agu Adv. 2(1), e2020AV000321 (2021).

Hoyt, A. M. et al. Widespread subsidence and carbon emissions across Southeast Asian peatlands. Nat. Geosci. 13 (6), 435 (2020).

Li, F. et al. Bacterial community structure after Long-term organic and inorganic fertilization reveals important associations between soil nutrients and specific taxa involved in nutrient transformations. Front. Microbiol. 8, 187 (2017).

Tao, F. et al. Microbial carbon use efficiency promotes global soil carbon storage. Nature 618 (7967), 981–985 (2023).

Evans, S., Allison, S. & Hawkes, C. Microbes, memory and moisture: predicting microbial moisture responses and their impact on carbon cycling. Funct. Ecol. 36 (6), 1430–1441 (2022).

Lamit, L. J. et al. Peatland microbial community responses to plant functional group and drought are depth-dependent. Mol. Ecol. 30 (20), 5119–5136 (2021).

Moorhead, D. et al. Interacting microbe and litter quality controls on litter decomposition: A modeling analysis. PLOS ONE 9(9), e108769 (2014).

Anderson, T. H. & Domsch, K. H. The metabolic quotient for CO2 (qCO2) as a specific activity parameter to assess the effects of environmental conditions, such as ph, on the microbial biomass of forest soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 25 (3), 393–395 (1993).

Li, J., Shangguan, Z. & Deng, L. Dynamics of soil microbial metabolic activity during grassland succession after farmland abandonment. Geoderma 363, 114167 (2020).

Risch, A. C. et al. Drivers of the microbial metabolic quotient across global grasslands. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 32 (6), 904–918 (2023).

Xu, X. F. et al. Global pattern and controls of soil microbial metabolic quotient. Ecol. Monogr. 87 (3), 429–441 (2017).

Hartman, W. H. & Richardson, C. J. Differential nutrient limitation of soil microbial biomass and metabolic quotients (qCO2): is there a biological stoichiometry of soil microbes?? Plos One 8(3), e57127 (2013).

Cao, Y. Q. et al. Soil microbial metabolic quotient in inner Mongolian grasslands: patterns and influence factors. Chin. Geogra. Sci. 29 (6), 1001–1010 (2019).

Sun, Y. et al. Effects of short-term precipitation reduction on soil organic carbon mineralization and organic carbon fractions in Hainan rubber forests. J. Trop. Ecol. 15 (03), 272–280 (2024).

Lei, C. et al. Effects of warming on soil microbial respiration and entropy in subtropical Chinese Fir (Cunninghamia lanceolata) plantation. Acta Ecol. Sin. 44 (14), 6186–6194 (2024).

Jiang, Y. J. et al. Soil aggregate stratification of nematodes and microbial communities affects the metabolic quotient in an acid soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 60, 1–9 (2013).

Liu, S. G. et al. Temperature legacies predict microbial metabolic quotient across forest biomes. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 32 (1), 107–119 (2023).

Li, X. et al. Effects of drying-wetting cycle caused by rainfall on soil respiration: progress and prospect. Chin. J. Ecol. 38 (2), 567–575 (2019).

He, M. et al. Spatial distributions and key drivers of microbial necromass carbon in permafrost deposits across the Tibetan plateau. Chin. Sci. Bull. 69 (07), 925–938 (2024).

Jia, J., Li, X. & Feng, X. Effect of drainage on microbial transformation processes of soil organic carbon in two typical wetlands of China. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 35 (01), 133–140 (2024).

Zeng, X. M. et al. Local temperature increases reduce soil microbial residues and carbon stocks. Glob. Change Biol. 28 (21), 6433–6445 (2022).

Bhople, P. et al. Microbial necromass formation, enzyme activities and community structure in two alpine elevation gradients with different bedrock types. Geoderma 386, 114922 (2021).

Chen, Y. et al. Large-scale evidence for microbial response and associated carbon release after permafrost thaw. Glob Chang. Biol. 27 (14), 3218–3229 (2021).

Qiu, J. et al. Five-year warming does not change soil organic carbon stock but alters its chemical composition in an alpine peatland. Pedosphere 33 (5), 776–787 (2023).

Chen, X. et al. Analysis on the difference of microbial function gene in different grasslands of Sanjiangyuan National park. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 29 (03), 472–482 (2020).

Jiang, W. et al. Microbial genes for degrading plant-derived carbon are a key factor affecting soil respiration and temperature sensitivity in plateau peatlands. Pedosphere 34 (6), 1026–1037 (2024).

Vance, E. D., Brookes, P. C. & Jenkinson, D. S. An extraction method for measuring soil microbial biomass C. Soil Biol. Biochem. 19 (6), 703–707 (1987).

Wu, D. M., Guo j, F., Zhang, Z., Li, S. J. & Yang, Y. S. Elects of dissolved organic mater addition on Sol microbial respirlion and quolient values in a secondary castanopsis carlesii forest. Acta Eeologica Sinica. 38 (11), 3806–3815 (2018).

Zhang, X. & Amelung, W. Gas chromatographic determination of muramic acid, glucosamine, mannosamine, and galactosamine in soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 28 (9), 1201–1206 (1996).

Shi, Y. et al. Spatial scale affects the relative role of stochasticity versus determinism in soil bacterial communities in wheat fields across the North China plain. Microbiome 6, 27 (2018).

Cai, M. Research on Soil Elemental Stoichiometry and its Key Influencing Factors in Larix principis-rupprechtii Plantations at Mt. Taiyue (Beijing Forestry University, 2021).

Bouyoucos, G. J. Hydrometer method improved for making particle size analyses of Soils1. Agron. J. 54, 464–465 (1962).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Matsuura, Y. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res. 53, D672–D677 (2025).

Ren, C. et al. Microbial traits determine soil C emission in response to fresh carbon inputs in forests across biomes. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 1516–1528 (2021).

He, H. et al. Soil microbial community and its interaction with soil carbon dynamics following a wetland drying process in mu Us sandy land. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 17 (12), 4199 (2020).

Liu, Q. et al. Characteristics of paddy soil organic carbon mineralization and influencing factors under different water conditions and microbial biomass levels. Environ. Sci. 42 (05), 2440–2448 (2021).

Chen, G. et al. Experimental demonstration of a Hybrid-Quantum-Emitter producing individual entangled photon pairs in the Telecom band. Sci. Rep. 6(1), 26680 (2016).

Deng, D. et al. Zhan, g.X.-H.,. Influences of soil moisture on soil respiration. For. Res. 22(5), 722–727 (2009).

Ye, J. et al. Compensatory thermal adaptation of soil microbial respiration rates in global croplands. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 34, e2019GB006507 (2020).

Zhao, X. C. et al. Mean annual temperature and carbon availability respectively controlled the contributions of bacterial and fungal residues to organic carbon accumulation in topsoil across china’s forests. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 32 (1), 120–131 (2023).

Zhang, Q. et al. The contribution of microbial necromass carbon to soil organic carbon in soil aggregates. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 190, 104985 (2023).

Schweigert, M. et al. Fate of ectomycorrhizal fungal biomass in a soil bioreactor system and its contribution to soil organic matter formation. Soil Biol. Biochem. 88, 120–127 (2015).

Zhang, B. et al. Research progress on accumulation, turnover and stabilization of microbial residues in soil. Acta Pedol. Sin. 59 (06), 1479–1491 (2022).

Hu, Y. et al. Grassland degradation-induced soil organic carbon loss associated with micro-food web simplification. Soil Biol. Biochem. 201, 109659 (2025).

Barnard, R. L., Osborne, C. A. & Firestone, M. K. Responses of soil bacterial and fungal communities to extreme desiccation and rewetting. ISME J. 7, 2229–2241 (2013).

Haocai, W. A. N. G. et al. Spatial distribution and drivingmechanism of soil bacterialcommunities in the wetland of Zoige plateau. Acta Ecol. Sin. 41 (7), 2663–2675 (2021).

Liu, F. et al. Altered microbial structure and function after thermokarst formation. Glob. Change Biol. 27 (4), 823–835 (2021).

Tkacz, A. et al. Stability and succession of the rhizosphere microbiota depends upon plant type and soil composition. ISME J. 9 (11), 2349–2359 (2015).

Bogati, K. & Walczak, M. The impact of drought stress on soil microbial community, enzyme activities and plants. Agronomy 12(1), 189 (2022).

Rodríguez-Iturbe, I. et al. Challenges in humid land ecohydrology: interactions of water table and unsaturated zone with climate, soil, and vegetation. Water Resour. Res. 43, W09301 (2007).

Xia, S. et al. Patterns and determinants of plant-derived lignin phenols in coastal wetlands: implications for organic C accumulation. Funct. Ecol. 37 (4), 1067–1081 (2023).

Huang, R. et al. High stability and metabolic capacity of bacterial community promote the rapid reduction of easily decomposing carbon in soil. Commun. Biology. 4 (1), 1376 (2021).

Sapkota, A. et al. Isolation, characterization, and screening of Antimicrobial-Producing actinomycetes from soil samples. Int. J. Microbiol. 2020 (1), 2716584 (2020).

Montecchia, M. S. et al. Pyrosequencing reveals changes in soil bacterial communities after conversion of Yungas forests to agriculture. PLOS ONE 10(3), e0119426 (2015).

Kim, H. S. et al. Diversity and composition of soil Acidobacteria and Proteobacteria communities as a bacterial indicator of past land-use change from forest to farmland. Sci. Total Environ. 797, 148944 (2021).

Burns, R. G. et al. Soil enzymes in a changing environment: current knowledge and future directions. Soil Biol. Biochem. 58, 216–234 (2013).

Guo, X. et al. Gene-informed decomposition model predicts lower soil carbon loss due to persistent microbial adaptation to warming. Nat. Commun. 11 (1), 4897 (2020).

Hayakawa, C. et al. Biodegradation kinetics of monosaccharides and their contribution to basal respiration in tropical forest soils. Soil. Sci. Plant. Nutr. 57 (5), 663–673 (2011).

Schmidt, J. et al. Carbon input and crop-related changes in microbial biomarker levels strongly affect the turnover and composition of soil organic carbon. Soil Biol. Biochem. 85, 39–50 (2015).

Fujii, K. et al. Biodegradation of low molecular weight organic compounds and their contribution to heterotrophic soil respiration in three Japanese forest soils. Plant. Soil. 334 (1), 475–489 (2010).

Büttner, M. & Sauer, N. Monosaccharide transporters in plants: structure, function and physiology. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes. 1465(1), 263–274 (2000).

Niaz, K., F. Khan, and M.A. Shah, Chapter 18 - Analysis of carbohydrates (monosaccharides, polysaccharides), in Recent Advances in Natural Products Analysis. Elsevier. p. 621–633 (2020)

Li, C. et al. Change in deep soil microbial communities due to long-term fertilization. Soil Biol. Biochem. 75, 264–272 (2014).

Yang, L. et al. Lignin characteristics in a peat core of lake Dajiu. Geochimica 38 (02), 133–139 (2009).

Hodgkins, S. B. et al. Tropical peatland carbon storage linked to global latitudinal trends in peat recalcitrance. Nat. Commun. 9 (1), 3640 (2018).

Liu, X. Characterisation of the prokaryotic expression and properties of GDP-mannose pyrophosphorylase (GMPP). Shandong University (2008).

Seibold, G. M. et al. The glgB-encoded glycogen branching enzyme is essential for glycogen accumulation in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Microbiology 157(11), 3243–3251 (2011).

Xiong, M. et al. Microbial carbohydrate-active enzymes influence soil carbon by regulating the of plant- and fungal-derived biomass decomposition in plateau peat wetlands under differing water conditions. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1266016 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the financial support from the Natural Science Foundation of Sichuan Provence (No. 2023NSFSC0143), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31800458), and Sichuan Province Transportation Science and Technology Project: Research and Demonstration on Crucial Technologies of Wetland Eco-environment Protection Under the Influence of Highway Engineering on the Western Sichuan Plateau (No. 2019-ZL-19).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JW: Data curation, Writing-original draft; XMY: Data curation, Investigation; FSS: Data curation, Investigation; CYY: Data curation, Investigation; LQM; Data curation, Investigation; ZSZ: Investigation, Writing-review & editing, Software. KD: Investigation, Software, Writing-review & editing, Data curation, Funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, W., Xiong, M., Feng, S. et al. Water content alters soil organic carbon metabolism via microbial traits in Tibetan alpine peatlands. Sci Rep 15, 27793 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13788-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13788-5