Abstract

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for approximately 80–85% of all lung cancer cases. NSCLC is less sensitive to conventional chemotherapeutic agents, and high mortality and recurrence rates have become the impetus to find alternative therapies. Bovine lactoferrin (bLF) derived from bovine milk, has been shown to inhibit lung cancer growth through inhibiting angiogenesis and dampening inflammation in vivo. However, the mechanism by which bLF does this within the context of lung cancer is not well understood. Our study aims to untangle these mechanistic details to provide a biochemical and transcriptomic landscape in lung cancer cells treated with bLF. Treatment with bLF significantly decreased the viability of A549 and H-1299 lung carcinoma cells. In NSCLC cells, bLF induced S-phase cell cycle arrest and suppressed migratory capacity. Importantly, research findings bLF triggered mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptotic cell death via the intrinsic mitochondrial apoptotic pathway. Importantly, RNA sequencing revealed major transcriptomic changes in bLF treated cells, particularly in the focal adhesion, cell cycle, and proteoglycans in cancer pathways. Our findings further emphasizes the potent anti-cancer properties of bLF and highlight the potential for bLF as a natural product-derived alternative therapy for NSCLC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to the latest cancer report released by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC/WHO) in 2020, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for approximately 80–85% of all lung cancers1,2. Though the survival time of patients with advanced NSCLC has significantly prolonged with the advent of targeted therapy and immunotherapy3,4, NSCLCs have also become resistant to these lines of therapies5. Moreover, resistance to chemotherapy, the first-line treatment for NSCLC, also occurs in these patients6. There remains a dire need for alternative lines of treatment for NSCLC.

Natural compounds have received increasing attention for the prevention and treatment of cancer due to its low toxicity and multi-faceted biological actions. Bovine lactoferrin (bLF) is a natural glycoprotein derived from bovine milk and have reported anti-cancer effects in oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC)7 and esophageal and colon cancer8 cells. Within the context of lung cancer, bLF has been shown to be a potent angiogenesis and inflammation inhibitor in NSCLC cells, A549 cells9. Therefore, bLF has certain therapeutic potential in the treatment of lung cancer. Moreover, recombinant human lactoferrin (rhLF) has been shown to exhibit selective anti-cancer effects in A549 cells, not in non-cancer cell lines10. Despite the known anti-cancer properties of bLF in NSCLC cells, the underlying mechanism behind this phenomenon is not well elucidated, let al.one at the transcriptomic level. Our current study aims to address this and to provide the mechanistic evidence behind the anti-cancer effects of bLF on NSCLC cells.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and reagents

The Human lung adenocarcinoma cell line A549 was obtained from the cell bank of Lanzhou Minhai Bioengineering kindly (Lanzhou, China). A549 cells were maintained in F12 medium (Lanzhou Minhai Bioengineering Co. Lanzhou, China) containing 10% FBS (Lanzhou Minhai Bioengineering Co, Lanzhou, China) and 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen, CA, USA). The Human Non-small cell lung cancer cell line H-1299 was obtained from the cell bank of Wuhan Servicebio Bioengineering kindly (Wuhan, China). H-1299 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 (Lanzhou Minhai Bioengineering Co. Lanzhou, China) containing 10% FBS ((Lanzhou Minhai Bioengineering Co, Lanzhou, China). All cells were maintained at 37℃ and 5% CO2. Bovine lactoferrin (bLF) was purchased from MacKlin Inc. (Shanghai, China).

Assessing the cytotoxicity of bLF

Cytotoxicity was evaluated the CCK‑8 assay (Solarbio Science Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). Cells were treated different bLF concentrations (0, 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, 2.5, 3.0 and 4.0 mg/mL) for either 24–48 h before adding 10% CCK‑8 solution to each well. The OD at 450 nm measured on a microplate reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA).

Colony formation assay

Cells treated with varying concentrations of bLF were incubated for approximately 10 days (media change every 3 days) before fixing with 4% paraformaldehyde, and staining in 0.5% crystal violet. Colonies were then visualized under a phase contrast microscope (Olympus Corporation, Japan).

Cell cycle assay

Cells at 60–70% confluency were treated with bLF (0, 0.5, 1.0 and 1.5 mg/mL) for 24 h before fixing in cold-ethyl alcohol overnight at 4℃. Washed cells were then labeled with propidium iodide (PI)/RNase Staining Buffer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) before analyzing using the Attune NXT acoustic cytometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA).

Wound healing assay

A fully confluent monolayer of cells in 6-well plates were scratched vertically with a 200µL pipette tip and replaced with medium containing different concentrations of bLF (0, 0.5, 1.0 and 1.5 mg/mL). The wound area was imaged at 0, 12 and 24 h post-treatment in the same trabecular area under a phase contrast microscope (Olympus Corporation, Japan).

Cell apoptosis assay

An annexin V- FITC/PI staining kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) was used determine the number of apoptotic cells upon treatment with bLF (0, 0.5, 1.0 and 1.5 mg/mL) after 24 h by flow cytometry (CytoFLEX, Beckman Coulter, CA, USA).

Hoechst 33,342 staining

Hoechst 33,342 (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) staining was used to observe the cells morphology post-treatment with bLF (0, 0.5, 1.0 and 1.5 mg/mL) for 24 h and imaged under a fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corporation, Japan).

Mitochondrial membrane potential

Mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) was analyzed using a Mitochondrial and Apoptosis Assay Kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). Cells were treated with bLF (0, 0.5, 1.0 and 1.5 mg/mL) for 24 h, before measuring fluorescence intensity using a fluorescence microscope.

ROS assay

Intracellular ROS levels were measured using 2,7-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA, Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were incubated with DCFH-DA for 30 min at 37 °C before detecting fluorescence under a fluorescence microscope.

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis

RNA sequencing was performed using a BGI Optimal series two-module mRNA library construction kit (BGI-Shenzhen, China) for PE100 / PE150 sequencing on a G400 / T7 / T10 sequencer by combined probe anchor polymerization (cPAS). Functional annotation and pathway enrichment analysis of DEGs were performed using GO (Gene Ontology, GO) and KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) databases11.

RT-qPCR

Total RNA from cells were extracted in Trizol (TIANGEN BIOTECH, Beijing, China) and reverse transcribed using a cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad Laboratory, Hercules, CA, USA). cDNA was the amplified by qPCR by SYBR Green on an ABI PRISM 7500 cycler (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The relative gene expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method. GAPDH expression was used to normalize the gene expression. The primer sequences are provided in Table 1.

Immunoblotting

Cells were harvested and whole-cell extracts prepared in RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) before quantifying using the BCA Protein Assay kit (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology, Beijing, China). The samples were separated by 10–12% SDS-PAGE, and then electro-transferred onto PVDF membranes (Millipore, Berlington, MA, USA). The incubated antibodies include P21 (#10355-1-AP, 1:1000, Proteintech, China), CDK2 (#10122-1-AP, 1:1000, Proteintech, China), E-cadherin (#20874-1-AP, 1:1000, Proteintech, China), SNAIL1 (#13099-1-AP, 1:1000, Proteintech, China), P53 (#10442-1-AP, 1:1000, Proteintech, China), Casepase-3/P17/P19 (#66470-2-Ig, 1:1000, Proteintech, China), Bax (#50599-2-Ig, 1:1000, Proteintech, China), Bcl-2 (#12789-1-AP, 1:1000, Proteintech, China), Cytochrome C (10993-1-AP, 1:1000, Proteintech, China), CyclinA1 (#HA500287, 1:1000, HUABIO), Caspase-9 (#ET1610-95, 1:1000, HUABIO), GAPDH (#ET1601-4, 1:1000, HUABIO). Immunoblotting was visualized using ECL Blotting Substrate (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). GAPDH was used as the loading control, and quantified using the Image J software for each protein band.

Statistical analysis

Comparative statistics were done by one-way ANOVA and Student’s t-test in GraphPad Prism 8 software (GraphPad Software, Inc.). Unless otherwise stated, data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of at least three independent experiments. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (*** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01 and * p < 0.05).

Results

BLF exhibits toxicity toward lung cancer cells, as demonstrated in previous studies9. The CCK-8 assay revealed that higher bLF concentrations progressively reduced the viability of both A549 and H-1299 cells (Fig. 1A), confirming its dose-dependent inhibitory effect on non-small cell lung cancer. Furthermore, increasing the concentration of bLF also suppressed the proliferation of A549 cells (Fig. 1B-D). Further investigations will focus specifically on the A549 cell line. To investigate the mechanism behind this, we assessed whether bLF induces cell cycle arrest. A549 cells treated with bLF resulted in the significant increase of the percentage of cells entering S-phase and a decrease in the percentage of cells in G0/G1 phase (Fig. 2A-B). Consistent with this, the expression level of cell cycle-related p21 mRNA and protein was increased, coinciding with the decrease in CDK2 and cyclin A1 levels, proteins that interact in the cell cycle to regulate the transition from S phase to G2 phase, and then to M phase (Fig. 2C-E). Overall, we show that bLF can induce S-phase arrest in A549 cells. The ability of bLF to alter cell migration was then assessed using a scratch-wound healing assay. Compared to untreated cells, bLF treatment significantly inhibited cell migration in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3A). The expression levels of molecules associated with cell migration, E-cadherin was increased, while MMP-2, protein related to cancer invasion, and Snail, the transcription factor that regulates MMP-2, decreased (Fig. 3B-D). Those results showed that bLF can inhibit A549 cell migration.

Effects of bLF on proliferation, viability, morphology and proliferation of A549 cells in vitro. (A) The CCK-8 assay was performed to determine the viability of A549 and H-1299 cells after treatment with different doses of bLF for 24, and 48 h. (B) Microscopic observation of A549 cell morphology after 12 h and 24 h of treatment with different doses of bLF. (C) Colony formation assay of cell proliferation. The bLF concentrations were 0, 0.5, 1.0 and 1.5 mg/mL. (D) Quantitative results of colony formation. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001.

Effects of bLF on cell cycle in A549 cells. (A, B) A549 cell cycle distribution was detected using flow cytometry after treated with different concentrations of bLF. (C) RT-qPCR to detect the expression levels of cycle-related genes (CDK2, P21 and CyclinA1). (D) Western blot to detect the expression levels of cycle-related proteins (CDK2, P21 and CyclinA1). (E) Quantitative analysis of the cell cycle-associated proteins. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001.

bLF inhibits migration of A549 cells. (A) Wound healing assay to detect the effects of bLF on A549 cells. (B) RT-qPCR to detect the expression levels of migration-related genes (E-cadherin, Snail, and MMP-2). (C) Western blot to detect the expression levels of migration-related proteins (E-cadherin, Snail, and MMP-2). (D) Quantitative analysis of migration -associated proteins. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001.

Recombinant human LF (rhLF) has been previously shown to trigger apoptosis in A549 cells10. We wanted to see whether this also occurs with bLF. Hoechst 33,342 staining revealed that cells treated with bLF had typical apoptotic morphological hallmarks(Fig. 4A). Annexin V/propidium iodine staining confirms that bLF treated cells are undergoing apoptosis (Fig. 4B). These results showed that bLF can induce apoptosis of A549 cells. To further tease the apoptotic pathway bLF is triggering, we hypothesize that the intrinsic mitochondrial apoptotic pathway is involved based on previous findings that caspase 3, an essential component of this pathway, is activated in cells treated with rhLF12. Mitochondrial damage is an important indicator of early apoptosis, and mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) deficiency is a main manifestation of mitochondrial damage. Mitochondrial membrane potential assay was used to detect the effect of bLF on the integrity of the mitochondrial membrane in A549 cells. Mito-Tracker (red) aggregates represent intact stromal metal membranes, whereas green Annexin V (green) represents damaged stromal metal membranes. Compared to controls, bLF treatment induced MMP damage in A549 cells coinciding with an increase in apoptosis (Fig. 4C). Mitochondrial dysfunction and alterations in mitochondrial potential may also interfere with intracellular ROS levels13. To determine whether intracellular ROS levels are changed upon bLF treatment, intracellular ROS levels were examined. Increasing concentrations of bLF increased intracellular ROS production (Fig. 4D), demonstrating that bLF can trigger ROS production. Furthermore, validation by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) revealed that the expression levels of P53, Bax, and Caspase-3 genes were upregulated, while Bcl-2 gene expression was downregulated (Fig. 4E). Previous research established that mitochondrial apoptotic pathway activation induces cytochrome C release, facilitating apoptosome formation and subsequent Caspase-9/Caspase-3 cascade activation, culminating in apoptosis. Consistent with mitochondrial pathway involvement, bLF treatment activated caspase-3, caspase-9, and Cyto-C while upregulating p53 and mitochondrial Bax, accompanied by reduced Bcl-2 expression. In conclusion these findings demonstrate that bLF triggers apoptosis via the mitochondrial pathway (Fig. 4F-I).

bLF induces apoptosis in A549 cells and induces A549 apoptosis through the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway. (A) Hoechst 33,342 staining to detect the morphological changes in A549 cells. 1–4: The bLF concentrations were 0, 0.5, 1.0 and 1.5 mg/mL. (B) Flow cytometry assay to determine the apoptosis rate of A549 cells after treated with bLF. (C) The results of mitochondrial membrane potential staining. (D) The results of intracellular ROS levels in A549 cells after bLF treated. 1–4: The bLF concentrations were 0, 0.5, 1.0 and 1.5 mg/mL. (E) RT-qPCR to detect the expression levels of mitochondrial apoptosis-related genes (Caspase-3, P53, Bcl-2 and Bax). (F, H) Western blot to detect the expression levels of mitochondrial apoptosis-related proteins (Caspase-3, Caspase-9, P53, Bcl-2, Bax and cyto-C). (G, I) Quantitative analysis of mitochondrial apoptosis-related proteins. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001.

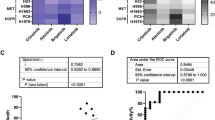

We then performed a transcriptomic screen on bLF treated cells. An inter-sample expression and correlation analysis between bLF treated cells and the control group shows a high degree of experimental reproducibility (Fig. 5A). Comparison with controls identified 637 differentially expressed mRNAs, including 291 up-regulated and 346 down-regulated genes (Fig. 5B-C). Based on transcriptomic analysis, the most significantly differentially expressed genes were screened and validated at the genetic level. The results demonstrated that the expression levels of genes up-regulation (U2AF1, EIF4EBP3, and LDLRAD2) and down-regulation (PRR5-ARHGAP8, RGPD2, and TSPAN2) were consistent with the transcriptomic screening results (Fig. 5D). KEGG enrichment analysis revealed that these differentially expressed mRNAs were significantly enriched in several cellular pathways, including focal adhesion, cell cycle, and proteoglycans in cancer, among others (Fig. 5E). An examination of the intersection sets among the groups using a VENN/UpSetR diagram showed that 15,789 common genes were present in both experimental groups (Fig. 5F). These 15,789 genes were further classified using KEGG pathway annotation (Fig. 5G) and found that these genes were primarily found in pathways related to neurodegenerative diseases. Overall, bLF treatment induces a transcriptomic profile consistent with cell cycle arrest and tumor migration.

Analysis of mRNA expression difference. (A) Heatmap of Correlation Coefficients for Exp_A549 and Con_A549 Samples. The X and Y axes represent individual samples, with the color indicating the correlation coefficient. Darker colors signify higher correlations, while lighter colors indicate lower correlations. (B) Differential Expression Volcano Plot. The X-axis displays the log2-transformed fold change, and the Y-axis shows the -log10-transformed significance value. Red dots represent up-regulated differentially expressed genes (DEGs), blue dots represent down-regulated DEGs, and gray dots represent non-differentially expressed genes (Non-DEGs). (C) Clustering Heatmap of DEGs. Expression values are depicted in varying colors, with high expression genes colored red and low expression genes colored blue. The intensity of the red color indicates a higher expression level, whereas the intensity of the blue color signifies a lower expression level. (D) RT-qPCR to detect the expression levels of upregulated and downregulated genes. (E) KEGG Pathway Enrichment Analysis of DEGs. The X-axis represents the enrichment ratio, and the Y-axis lists the KEGG Pathways. The bubble size reflects the number of genes annotated to a specific KEGG Pathway, while the color denotes the enrichment significance value. A redder color indicates a smaller significance value. (F) VENN/UpSetR Plot of Gene Expressions. Each circle represents a set of genes, and the overlapping areas of different circles indicate the intersection of these gene sets. The non-overlapping portions signify unique gene sets, and the numbers on the plot represent the gene count in the corresponding regions. (G) Detailed KEGG Pathway Enrichment Analysis of DEGs. Based on kegg_pathway annotation classification, the phyper function in R software was utilized for enrichment analysis to calculate P-values. Subsequently, FDR correction was applied to the P-values to obtain Q-values. Typically, functions with Q-values ≤ 0.05 are considered significantly enriched.

Discussion

Lactoferrin is an iron-binding glycoprotein in the transferrin family. Several studies have reported the use of bLF for the treatment of several diseases. Numerous studies have confirmed its strong anti-tumor ability8. In the present study, we demonstrate the potent anti-cancer effects of bLF on NSCLC cells. It was found that bLF could inhibit the viability of non-small cell lung cancer cells (both A549 and H-1299 cell lines).

The anti-proliferative effects of anti-cancer drugs are often associated with cell cycle inhibition, and therapeutic approaches targeting the cell cycle have become routine in cancer treatment14. Cell cycle regulation is dependent on the cell cycle protein family and the CDK protein family. Decrease or dysregulation of the cell cycle protein A/CDK2 complex may lead to cell arrest in the S phase. In this study, the percentage of S-phase in A549 cells was significantly increased, coinciding with a reduction in G0/G1-phase cells after treatment with bLF. In addition, bLF treatment inhibited the expression of cell cycle-related protein CyclinA1 and CDK2, while promoted the expression of p21 to prevent the normal proliferative activities of A549 cells. It has been shownthat bLF down-regulates the expression of Snail transcription factor and vimentin, whilst upregulating calmodulin (cadherin) and suppressing IL-6/STAT3 gene expression, thereby regulating the EMT process and affecting the migration and invasion in glioma cells15. The scratch-wound healing assay showed that bLF inhibited A549 cell migration in a concentration-dependent manner and found that this was consistent with the downregulation of Snail and MMP-2 were and the upregulation of E-cadherin (Fig. 3B-D).

Apoptosis, or programmed cell death, is a series of biochemical processes that are characterized by morphological changes and cell death. This process is essential for the cell cycle in multicellular organisms and is mainly characterized by nuclear division, cell shrinkage, mRNA decay, and DNA breakage. Mitochondria are essential for cell survival and constitute the cornerstone of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway16. Mitochondria are not only involved in energy metabolism and the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), but also control cell survival and are known as the “power factories” of cells. It has been shown that bLF can cause a shift in mitochondrial permeability and trigger apoptotic effects in leukemic cells16. Consistent with this, we showed that bLF can trigger mitochondria-dependent apoptosis and mitochondrial membrane potential depolarization in NSCLC cells. Transcriptomics systematically studies the composition, abundance, structure, and functions of RNA molecules, primarily targeting mRNAs (though non-coding RNAs are often included). Through high-throughput sequencing methods like RNA-seq, it enables genome-wide profiling of gene expression patterns in cells, tissues, or organisms under specific conditions11. Based on our transcriptomic findings, the inhibitory effect on A549 cell proliferation affected pathways related to cell adhesion, cell cycle, proteoglycans in cancer pathways. Furthermore, the examination of apoptosis-related factors of genes and proteins revealed that bLF up-regulated the pro-apoptotic protein Bax down-regulated the anti-apoptotic regulator Bcl-2, thereby to prevent them forming a complex. This causes the loss of the electron chain complex in the mitochondrial membrane, and inhibits the intracellular redox metabolism. The activation of cytochrome C, caspase-3, and caspase-9 demonstrates that bLF induces apoptotic cell death in A549 cells through elevated intracellular ROS levels and mitochondrial damage.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our results confirm that bLF elicits inhibitory effects on A549 cells proliferation, cycle progression, migration. We show mechanistically that bLF can trigger apoptosis and mitochondrial dysfunction through MMP loss. Transcriptome sequencing analysis identified key differentially expressed genes potentially associated with bLF’s anti-NSCLC effects. These genes participate in cell cycle regulation, proteoglycan synthesis, and related signaling pathways. Taken together, our data suggested that bLF may be a natural agent that can therapeutically be use to treat lung cancers. Although these study findings were limited to in vitro, but also provided some experimental evidence for the development of novel natural anti-tumor agents, and offered new transcriptomic insights into the effect of bLF on NSCLC cells.

Data availability

The original data supporting the conclusions of this manuscript will be provided by authors to any qualified researcher without reservation. Raw data have been deposited to National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) under the BioProject number PRJNA1244310 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/search/all/?term=PRJNA1244310+). (Please contacted the corresponding author if someone wants to request the data from this study). The remaining data are available in the accompanying article, supplementary information, or source data files attached to this manuscript.

References

Sung, H. et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71 (3), 209–249. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660 (2021).

Filho, A. M. et al. The GLOBOCAN 2022 cancer estimates: data sources, methods, and a snapshot of the cancer burden worldwide. Int. J. Cancer. 156 (7), 1336–1346. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.35278 (2025).

Duma, N., Santana-Davila, R. & MolinaJR Non-Small cell lung cancer: epidemiology, screening, diagnosis, and treatment. Mayo Clin. Proc. 94 (8), 1623–1640. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.01.013 (2019).

SiegelRL, MillerKD, FuchsHE & JemalA Cancer statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71 (1), 7–33. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21654 (2021).

Shergold, A. L., Millar, R. & Nibbs, R. J. B. Understanding and overcoming the resistance of cancer to PD-1/PD-L1 Blockade. Pharmacol. Res. 145, 104258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2019.104258 (2019).

Ashrafi, A. et al. Current landscape of therapeutic resistance in lung cancer and promising strategies to overcome resistance. Cancers (Basel). 14 (19), 4562. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14194562 (2022).

Li, H. et al. The combination of two bioactive constituents, lactoferrin and linolenic acid, inhibits mouse xenograft esophageal tumor growth by downregulating lithocholyltaurine and inhibiting the JAK2/STAT3-Related pathway. ACS Omega. 5 (33), 20755–20764. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.0c01132 (2020).

Cao, X. et al. Lactoferrin: A glycoprotein that plays an active role in human health. Front. Nutr. 9, 1018336. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.1018336 (2023).

Tung, Y. T. et al. Bovine lactoferrin inhibits lung cancer growth through suppression of both inflammation and expression of vascular endothelial growth factor. J. Dairy. Sci. 96 (4), 2095–2106. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2012-6153 (2013).

Olszewska, P., Pazdrak, B. & Kruzel, M. L. A novel human Recombinant lactoferrin inhibits lung adenocarcinoma cell growth and migration with no cytotoxic effect on normal human epithelial cells. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. (Warsz). 69 (1), 33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00005-021-00637-2 (2021).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Matsuura, Y. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res. 53 (D1), D672–D677. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae909 (2025).

Delierneux, C. et al. Mitochondrial calcium regulation of redox signaling in cancer. Cells 9 (2), 432. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9020432 (2020).

Liu, T. et al. Identifying optimal first-line immune checkpoint inhibitors based regiments for advanced non-small cell lung cancer without oncogenic driver mutations: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. PLoS One. 18 (4), e0283719. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0283719 (2023).

Cutone, A. et al. Native and iron-saturated bovine lactoferrin differently hinder migration in a model of human glioblastoma by reverting epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition-like process and inhibiting interleukin-6/STAT3 axis. Cell. Signal. 65, 109461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cellsig.2019.109461 (2020).

Kashyap, D., Garg, V. K. & Goel, N. Intrinsic and extrinsic pathways of apoptosis: role in cancer development and prognosis. Adv. Protein Chem. Struct. Biol. 125, 73–120. 10.1016 /bs.apcsb.2021.01.003 (2021).

Mader, J. S., Salsman, J., Conrad, D. M. & Hoskin, D. W. Bovine lactoferricin selectively induces apoptosis in human leukemia and carcinoma cell lines. Mol. Cancer Ther. 4 (4), 612–624. https://doi.org/10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-04-0077 (2005).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all of the people who participated in the studies.

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Gansu Province (23JRRA717), Central University of basic scientific research business special funds project (31920250076) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (31860696, 22104045).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JS and YZ completed the theoretical research, technical method design, experiment and analysis, and the writing and revision of the paper. ML and GC performed experiments and processed the results. CL assisted with experiments and analysis. AI assisted with the experimental design, wrote, edited and reviewed this manuscript. ZM and HZ supervised the entire process, provided research guidance, demonstrated technical methods, and wrote and reviewed the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Su, J., Zhao, Y., Li, M. et al. Bovine lactoferrin drives cell cycle arrest and alters the transcriptomic profile of NSCLC cells. Sci Rep 15, 27850 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13796-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13796-5