Abstract

White matter hyperintensities (WMHs) are prevalent in older age and are associated with cognitive decline. The location and extent of WMHs likely influences the relationship with behavior. Identifying which tracts are more likely impacted by WMHs might enable better understanding of which behaviors are affected. Therefore, this study aimed to i) identify which white matter tracts are most affected by WMHs, and ii) identify tracts where the presence of WMHs is associated with poorer cognitive scores. Participants (N = 212, 20–80 years) completed the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA). WMHs were manually delineated on FLAIR scans. In DSIStudio, we used the Human Connectome Project 1065FIB template to track how many fibers of each white matter tract intersected each participant’s WMH map. Values obtained represent disconnection associated with WMHs. These scores were correlated with age, MoCA total and memory index scores. There was significantly more disconnection with older age in the right arcuate fasciculus, extreme capsule, frontal aslant tract, bilateral inferior, middle and superior longitudinal fasciculi, and the corpus callosum. Disconnection associated with WMHs in the right superior longitudinal fasciculus was significantly associated with a lower MoCA scores. Finally, disconnection in the right extreme capsule, middle and superior longitudinal fascicli, and bilateral frontal aslant tracts were significantly associated with lower MoCA memory index scores. This study highlights the prevalence of WMHs across the lifespan and demonstrates a clear relationship between tract-specific WMHs and cognition. Age-related white-matter degeneration was pronounced in many association fibers, particularly in the right hemisphere. These data suggest age related disruption of specific white matter tracts represents a clear and present risk factor for global cognition and memory as we age.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Many structural brain changes occur across the lifespan, one of which is the subtle, progressive accrual of white matter hyperintensities (WMHs), a neuroimaging marker of small vessel disease1,2. The presence of WMHs is often associated with chronic, insufficient cerebrovascular supply and has previously been linked to cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, and high body mass index (BMI) scores3. The presence of WMHs is common in individuals older than 45 years2, and WMHs are seen in more than 90% of individuals by the age of 654. Recent research also indicates that WMHs can present much earlier than previously expected, with frequent occurrence in younger individuals5,6. There is a large body of research suggesting that the presence of WMHs is associated with behavioral changes6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13, though the exact nature of this relationship is not entirely clear. For example, several prior studies discuss the presence of WMHs affecting executive functions and memory14,15,16 whilst others have found a more global impact on cognition9.

There is little research into the impact of WMHs on global cognition and memory in younger individuals; however, there is a growing consensus that WMHs are associated with age-related cognitive decline and mild cognitive impairment in older age8,17,18. Silbert and colleagues recently reported increased WMH burden in individuals in the early, pre-symptomatic stages of mild cognitive impairment (MCI)19. Similarly, Tosto and colleagues found evidence that increased WMH severity is associated with a more rapid decline in cognitive abilities in those experiencing mild cognitive impairment 20. Finally, there is data supporting the idea that severe WMH burden in mild cognitive impairment may play a role in the conversion from mild cognitive impairment to dementia11,21,22,23,24,25,26, and that increased WMHs are common in individuals diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease27. Together with hippocampal atrophy, increased WMH severity in Alzheimer’s disease is thought to be associated with increased cognitive impairment28, and accumulation of WMHs may predict Alzheimer’s disease development29. While prior research clearly establishes a relationship between WMH load and cognition, few studies have examined this effect in detail. One recent study by Yoshida and colleagues found differences between cognitively healthy adults, adults with mild cognitive impairment, and adults with Alzheimer’s Disease in both extent and spatial location of WMHs30, suggesting that spatial characteristics of WMH distribution carry clinical value. It is also possible that younger individuals with increased WMHs are more likely to develop cognitive impairment or dementia earlier in life, although this should be formally tested in future studies.

To understand the impact of WMHs across the lifespan, the extent and spatial location is likely important because the size and location will determine how much, and which white or gray matter is damaged. As long-range white matter fiber bundles are important for coordinating behaviors, individuals with high WMH load, or those with WMHs directly impacting long fiber bundles may be more likely to have a cognitive impairment. Thus, identifying the common locations of WMHs may be crucial to understanding the relationship between WMHs and global cognition.

Therefore, the main aims of the current study are to (i) identify which white matter tracts are most affected by WMHs, and (ii) to see if there are specific white matter tracts where disconnection associated with WMHs is related to poorer global cognition and memory scores in a large cohort of healthy older adults. We chose the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) as our primary measure of cognition as this test gives an overview of general cognition. We further focused on the MoCA memory index score as it is typically used to identify individuals who may have mild cognitive impairment31 or who might convert from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease.

Methods

Participants

Participants (N = 212) were part of the ABC@USC Repository32, an ongoing original cross-sectional cohort study at the University of South Carolina, see Table 1 for full participant demographics. ABC@USC has the following exclusion criteria: anyone who has previously experienced a stroke, a diagnosis of a neurodegenerative disease or dementia (including Alzheimer’s disease, Lewy body dementia, Parkinson’s disease, or other dementias), any acute or chronic conditions which would limit their ability to participate, any severe current illnesses (e.g., cancer), and psychiatric diagnosis (e.g., schizophrenia), or anyone with a BMI of > 42. All participants who had complete demographic and behavioral data and had completed an MRI scan were included in this study. University of South Carolina Institutional Review Board approval was obtained, followed by written informed consent provided by all participants at the time of enrollment.

Behavioral testing

Researchers administering the cognitive battery had C-level qualifications and testing followed standardized procedures on either a laptop (MacBook Pro) or an iPad.

The primary cognitive measure to evaluate overall cognition was the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)33, a cognitive screening assessment sensitive to mild cognitive impairment. Researchers completed training for administration and scoring of the MoCA. Domain scores are obtained for each of the following cognitive domains: attention and concentration, executive functions, memory, language, visuoconstructional skills, and orientation. Total MoCA scores were calculated from these domain scores using the guidelines provided by the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center Uniform Data Set instruction manual for neuropsychological testing battery34 and were adjusted for educational level of the participant. We chose to focus on MoCA total score as a test of general cognition, and the memory subscore as it has previously been used to identify individuals who have mild cognitive impairment or may convert from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease31. Other subscores were not investigated in this study but could be explored in future studies. It should be noted that the MoCA is a limited cognitive test and does not represent a gold standard test for cognitive health and diagnostic prediction, therefore the results should be interpreted with caution.

At the time of behavioral testing, self-reported health measures were also collected, including presence of diabetes and hypertension. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated using participants’ height and weight.

Neuroimaging acquisition and preprocessing

Participants underwent MRI scanning on a Siemens Trio 3 T scanner with a 20-channel head coil. T1-weighted images were used for brain age estimation and were acquired using the following parameters: T1-weighted imaging (MP-RAGE) sequence with 1 mm isotropic voxels, 256 × 256 matrix size, 9° flip angle, and 92-slice sequence with repetition time (TR) = 2250 ms, inversion time (TI) = 925 ms, and echo time (TE) = 4.11 ms. Fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) scans were also acquired on the same scanner using the following parameters: TR = 5000 ms, TE = 387 ms, matrix = 256 × 256, FOV = 230 × 230 × 173 mm3, slice thickness = 1 mm, 160 sagittal slices.

For each participant, WMHs were manually delineated on the native-space FLAIR image in accordance with the STRIVE protocol (Standards for Reporting Vascular Changes on Neuroimaging)35. WMH masks were drawn over the scan for each participant using MRIcroGL. To account for variability of interpretation, the same trained individual (author SW) delineated WMHs for each participant and was blinded to behavior and demographic information. WMH identification was supervised by a neurologist (author LB) to ensure accurate delineation.

After delineating WMH maps on each participants FLAIR image, we used SPM12’s unified segmentation-normalization method36 to warp each participants’ native-space T1 scan to standard (MNI) space. The resulting spatial transform was applied to the native-space FLAIR scan as well as the hand-drawn WMH map. For each participant, WMH load was calculated as the volume in mm3 (the total number of voxels) corresponding to the WMH.

Statistical analysis with WMH load

To investigate the relationship between WMH burden and behavior, Kendall’s tau correlations were conducted between WMH load, MoCA total score, and MoCA memory index.

Tracking using WMH masks

In DSI Studio, we used the Human Connectome Project (HCP) 1065 FIB template in 1 mm resolution (HCP1065.1 mm.fib)37, which is a publicly available template downloaded from https://brain.labsolver.org/hcp_template.html37. The template was derived from 1065 individuals from the Human Connectome Project, and diffusion tensors were fitted using the b = 1000 s/mm2 data after gradient non-linearities correction37. The tensors were transformed into MNI space using HCP participant-specific volumetric transformations37,38. See Appendix 1 for a full list of tracts available in this template.

To identify which white matter tracts were likely disrupted by WMHs in each participant, we used this template to track how many fibers of each white matter tract intersected each participant’s WMH map. Specifically, in DSI studio we load each of the participants’ WMH maps into the HCP template. Then, using the in-built fiber count by region analysis, we track all fibers going through the WMH maps. The output for this analysis is the number of streamlines for each white matter tract that passes through the WMH map for each individual.

For tracts that are subdivided in the template into anatomically distinct segments (e.g., the superior longitudinal fasciculus [SLF], thalamic radiation, cingulum), we summed the values of all segments within each hemisphere for ease of analysis and interpretation, although we categorised tracts by laterality (left and right hemisphere). However, it should be noted that the summed segments represent distinct anatomical pathways.

We focus our analysis on association fibers (arcuate fasciculus [AF], cingulum, extreme capsule, frontal aslant tract [FAT], inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus [IFOF], inferior longitudinal fasciculus [ILF], middle longitudinal fasciculus [MLF], SLF and uncinate fasciculus [UF]), the fornix (projection fiber) and the anterior commissure and corpus callosum (commissural fibers). Given that the same template was used for tracking for each participant’s WMH mask, we used the raw number of streamlines (rather than accounting for intracranial volume or factors such as the length of white matter tract).

Association with behavior

To explore the relationship with behavior, the number of streamlines in each tract that intersected each WMH mask was correlated (Kendall’s tau correlation) separately with MoCA total score and MoCA memory scores, see Fig. 1.

Results

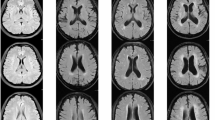

Participants had an average of 4.39 cm3 (SD = 4.66 cm)) of WMHs, see Fig. 2 for an overlay of WMHs. The average MoCA total score was 27.25/30 (SD = 2.47), participants had an average score of 13.26/15 (SD = 2.63) on the MoCA memory subtest.

Overlay of white matter hyperintensities across all participants. Red-yellow colors show where participants had white matter hyperintensities, where brighter colors indicate more participants. The color bar at the top provides a scale of how many participants have overlapping white matter hyperintensities. Note that the background brain image is the MNI152 template from MRIcroGL.

There was a positive correlation between WMH load and age (r = 0.393, p < 0.001), and a negative correlation between WMH load and MoCA total score (r = -0.248, p = 0.001) and MoCA memory index (r = -0.230, p = 0.003), see Fig. 3.

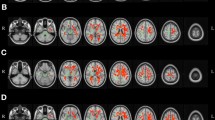

WMH analysis

When accounting for sex and education, disconnection associated with WMHs in 10 white matter tracts were significantly associated with increasing age, including right arcuate fasciculus (r = 0.265, p < 0.001), extreme capsule (r = 0.242, p < 0.001), frontal aslant tract (r = 0.279, p < 0.001), inferior longitudinal fasciculus (r = 0.288, p < 0.001), middle longitudinal fasciculus (r = 0.278, p < 0.001), and superior longitudinal fasciculus (r = 0.245, p < 0.001), left inferior longitudinal fasciculus (r = 0.219, p < 0.001), middle longitudinal fasciculus (r = 0.249, p < 0.001) and superior longitudinal fasciculus (r = 0.188, p < 0.001), and the corpus callosum (r = 0.178, p < 0.001), see Fig. 4 and Table 2. All analyses were corrected for multiple comparisons using Bonferroni correction. The adjusted significance level was p = 0.002 (0.05/24 = 0.002).

Visualization of the white matter tracts where increased WMH load was associated with older age, including the corpus callosum (purple), right arcuate fasciculus (pink), right extreme capsule (red), right frontal aslant tract (green), inferior longitudinal fasciculi (blue), middle longitudinal fasciculi (yellow) and superior longitudinal fasciculi (orange). Figures were generated by authors using DSIstudio (version Chen Nov 20 2023) using the Human Connectome Project 1065 template in 1 mm resolution (HCP1065.1 mm.fib)37, which is a publicly available template downloaded from https://brain.labsolver.org/hcp_template.html37.

When accounting for age and sex, disconnection associated with WMHs in the right superior longitudinal fasciculus was significantly associated with worse MoCA total scores, (r = -0.182, p < 0.001), see Fig. 5. Several other tracts approached significance, including right extreme capsule (r = -0.159, p = 0.004), middle longitudinal fasciculus (r = -0.154, p = 0.005), and frontal aslant tract (r = -0.148, p = 0.007), as well as left frontal aslant tract (r = -0.146, p = 0.007). Note that the MoCA is a limited cognitive test rather than a gold standard test for cognitive impairment, so results should be interpreted with caution and as preliminary findings.

Visualization of the white matter tract where increased WMH load was associated with worse MoCA memory index scores, the superior longitudinal fasciculus (orange). Figures were generated by authors using DSIstudio (version Chen Nov 20 2023) using the Human Connectome Project 1065 template in 1 mm resolution (HCP1065.1 mm.fib)37, which is a publicly available template downloaded from https://brain.labsolver.org/hcp_template.html37.

When accounting for age and sex, disconnection associated with WMHs in six white matter tracts was significantly associated with worse scores on the MoCA memory index, including the right extreme capsule (r = -0.169, p = 0.002), frontal aslant tract (r = -0.248, p < 0.001), middle longitudinal fasciculus (r = -0.189, p < 0.001), and superior longitudinal fasciculus (r = -0.223, p < 0.001), left frontal aslant tract (r = -0.192, p < 0.001), and superior longitudinal fasciculus (r = -0.193, p < 0.001), see Fig. 6 and Table 2. Disconnection in several tracts also approached significance including right inferior longitudinal fasciculus (r = -0.149, p = 0.006) and left middle longitudinal fasciculus (r = -0.156, p = 0.004). All analysis was corrected for multiple comparisons using Bonferroni correction (0.05/24 = 0.002).

Visualization of the white matter tracts where increased WMH load was associated with worse MoCA memory index scores, including the right extreme capsule (red), frontal aslant tracts (green), right middle longitudinal fasciculus (yellow) and superior longitudinal fasciculi (orange). Figures were generated by authors using DSIstudio (version Chen Nov 20 2023) using the Human Connectome Project 1065 template in 1 mm resolution (HCP1065.1 mm.fib)37, which is a publicly available template downloaded from https://brain.labsolver.org/hcp_template.html37.

Discussion

In this study, we examined which white matter tracts were most susceptible to age-related degeneration, and whether there was a relationship between these disruptions and cognitive performance. We identified several specific white matter tracts that were commonly affected by increased WMHs in older age, including many association fibers. Specifically, lower MoCA scores were associated with WMHs in the right superior longitudinal fasciculus, while WMHs in several association fibers were associated with lower scores on the MoCA memory index.

In line with previous literature, we confirmed high prevalence of WMHs in middle and older age39, and a positive association between WMH load and age9,11. Notably, we found that WMHs in the right hemisphere disrupted more white matter tracts than those in the left hemisphere, corroborating previous literature that has shown that individuals with mild cognitive impairment were more likely to have WMHs in the right ILF and IFOF than controls40, and suggesting that WMHs in the right hemisphere is particularly associated with behavioral impairment. This asymmetry in WMHs found in the current study may suggest that the right hemisphere typically ages differently to the left. There has been some research suggesting hemispheric differences in aging, with the right hemisphere aging more rapidly than the left (Goldstein & Shelly, 1981). It has also been suggested that the right hemisphere plays an important role in cognitive reserve, with Robertson (2014) suggesting that the structural integrity of the right prefrontal lobe and right inferior parietal lobe may partially mediate the protective effects of cognitive reserve41. Our results demonstrate that the right hemisphere is more likely to be impacted by WMHs, but it is possible that those with spared right prefrontal and inferior parietal lobes may be less likely to have behavioral changes typically associated with an increased WMH load.

Another striking finding of the current study was the disparity in WMH severity found in participants of similar ages (Fig. 3A). In the top right corner of the graph, there are participants who have particularly high WMH load, suggesting that some individuals may be particularly poor agers. Future studies could investigate if there are vascular risk factors, demographic factors, or genetic factors that influence this disparity in WMH load. It is also possible in these individuals that age-related small vessel diseases such as arteriolosclerosis and cerebral amyloid angiopathy contribute to WMH burden in these individuals, and this could be investigated further.

Many of the tracts most affected by WMHs in older age were long-range association tracts including the arcuate fasciculus, extreme capsule, frontal aslant tract, inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus, middle longitudinal fasciculi, and superior longitudinal fasciculus, which connect cortical areas within the same hemisphere. These tracts are typically thought to be critical for cognitive processes such as executive function, language, and memory42,43,44,45. Therefore, degradation of these tracts, potentially due to the presence of WMHs, may contribute to some of the age-related cognitive declines common in behaviors such as executive function and memory46,47,48. Although no participants in the current study had a diagnosis of dementia, many had WMHs in tracts that have previously been highlighted in Alzheimer’s or other related dementia research. For example, changes in the corpus callosum such as increased atrophy and increased WMH burden have been identified in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease49. Therefore, it is possible that this corpus callosum degradation is associated with cognitive decline50 and may be a potential biomarker for cognitive deficits preceding development of Alzheimer’s disease50,51, even in younger adults. Indeed, Jokinen and colleagues found that, in stroke, corpus callosum atrophy is associated with cognitive decline independently of age, education, and stroke-related factors52. Similarly, Qui et al. suggest that WMH burden in the corpus callosum may contribute to cognitive deficits in subcortical ischemic vascular disease53, and Chua and others used diffusion tensor imaging to highlight abnormalities in the corpus callosum, which are more common in older age51.

The main white matter tract where disconnection associated with WMHs was related to poorer cognitive scores was the superior longitudinal fasciculus. A previous study showed that higher WMH burden was related to worse diffusion in the superior longitudinal fasciculus (along with the forceps major, forceps minor, anterior thalamic radiation, cingulum, cortical spinal tract, inferior longitudinal fasciculus, and the uncinate fasciculus)54, highlighting how the presence of WMHs may disrupt connectivity in these long-range tracts. The superior longitudinal fasciculus is typically associated with language functions and connects posterior language areas to precentral gyrus and Broca’s area55. As some of the domains on the MoCA require language comprehension or production skills, it is possible that the association we found between MoCA scores, and the superior longitudinal fasciculus are related to these language components. Similarly, the disconnection associated with WMHs in the frontal aslant tract approached a significant relationship with MoCA total score. The frontal aslant tract is thought to connect Broca’s area to the supplementary motor area in both hemispheres and has been associated with speech functions56, in particular motor speech57. Bilateral damage to the frontal aslant tract has been found in individuals with Alzheimer’s disease, suggesting that the integrity of this tract may be important in cognitive decline, a finding which is substantiated by our results. It has also been reported that both the superior longitudinal fasciculus and frontal aslant tract are associated with poorer memory performance58, which may also explain the results of the current study.

In another study of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease, the largest volume of WMHs across the brain were found in the IFOF59. Our results corroborate this finding, as we found increasing disconnection associated with WMHs in the IFOF with older age. Although we did not find that disconnection in the IFOF was associated with cognitive impairment based on the MoCA total score, we did find that it negatively correlated with reduced scores on the MoCA memory index. Although not a comprehensive cognitive assessment, MoCA memory index scores are typically thought to be lower in individuals who convert from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease31, therefore, our results suggest that there is increased disconnection in the IFOF prior to a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. This is supported by previous work, with some studies highlighting that white matter changes in the right inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus were a good predictor of conversion from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease60.

Additionally, we found increased disconnection associated with WMHs in other association fibers correlated with lower MoCA memory index scores, including the FAT, MLF, and SLF. This finding is in line with research highlighting the involvement of association fibers in the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. However, our results indicate that the integrity of association fibers may be affected before a diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s disease. Our results also align with previous studies such work by Balado and colleagues (2022)61. Although they focus more on brain regions rather than specifically white matter tracts, one of their main findings was that temporal and juxtacortical WMHs were associated with episodic memory deficits. Similarly, we found that disconnection associated with white matter hyperintensities in juxtacortical white matter tracts such as the superior longitudinal fasciculus, along with other tracts that extend into the temporal lobe such as the extreme capsule and middle longitudinal fasciculus are also associated with lower MoCA memory index scores.

It is important to note that participant specific DTI data was not used throughout, and instead the same template (Human Connectome Project 1065 FIB template) was used to track how many streamlines of each fiber tract intersected each individual’s WMH maps. This method means that the costly and time-consuming collection of diffusion data is not required from each participant, and if results can be obtained from scans which are more routinely collected, it might be more clinically relevant and easier to replicate more widely. However, it is likely that there are interindividual differences in the exact structure, size, and location of each individual’s white matter tracts, which are not captured by using this method, and future research may be needed to capture these individual differences and to ascertain if there is upregulation or compensation as a response to disconnection in tracts.

Limitations

One of the limitations with the current study is that the MoCA was developed as a brief test for cognitive impairment and does not provide an extensive evaluation of cognitive function, therefore, we cannot form firm conclusions about the role of WMH load on structural connectivity in mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s disease.

Another limitation is that our sample is mainly comprised of white participants, making the results less generalizable to other races. Furthermore, there are more females than males. These numbers reflect ease of recruitment of some races and/or genders.

In addition, there are other factors that may have influenced the results which could be investigated in future studies, for example the influence of anxious or depressive symptoms. Similarly, we did not adjust our correlational analyses for BMI which has previously been associated with WMH severity3.

Finally, we did not investigate factors such as the number of times a WMH overlapped with a particular tract, or whether a single or multiple WMHs overlapped with a tract. This means we cannot make any conclusions about how a tract is disrupted or if there is a difference between disruption associated with one large WMH at a single point in the tract compared to multiple smaller WMHs along the length of the tract. Future research could incorporate measures such as number of WMHs along a tract to further investigate this.

Conclusions

This study provides novel evidence for which white matter tracts are most affected by WMHs in older age and identifies specific brain regions (i.e., white matter tracts) in which WMH presence is associated with poorer cognitive abilities in a population of older adults who self-identified as healthy. Our findings have implications for the role of disconnection associated with WMHs in long-range association fibers across the brain with older age, as well as the relationship with cognitive decline, suggesting that WMHs in these tracts may impact behavior before a diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s disease.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. All ABC data is available upon request at https://abc.sc.edu/abc-repository-data-requests/.

References

Christiansen, P., Larsson, H. B. W., Thomsen, C., Wieslander, S. B. & Henriksen, O. Age dependent white matter lesions and brain volume changes in healthy volunteers. Acta radiol. 35(2), 117–122. https://doi.org/10.1177/028418519403500203 (1994).

d’Arbeloff, T. et al. White matter hyperintensities are common in midlife and already associated with cognitive decline. Brain Commun. https://doi.org/10.1093/BRAINCOMMS/FCZ041 (2019).

Etherton, M. R., Wu, O. & Rost, N. S. Recent advances in leukoaraiosis: white matter structural integrity and functional outcomes after acute ischemic stroke. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 18(12), 1–13 (2016).

Longstreth, W. T. et al. Clinical correlates of white matter findings on cranial magnetic resonance imaging of 3301 elderly people. Stroke 27(8), 1274–1282. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.27.8.1274 (1996).

Hopkins, R. O. et al. Prevalence of white matter hyperintensities in a young healthy population. J. Neuroimaging 16(3), 243–251. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1552-6569.2006.00047.X (2006).

Karvelas, N. & Elahi, F. M. White matter hyperintensities: Complex predictor of complex outcomes. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 12, 30351. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.123.030351 (2023).

Prins, N. D. & Scheltens, P. White matter hyperintensities, cognitive impairment and dementia: an update. Nature Rev. Neurol. 11(3), 157–165. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2015.10 (2015).

Boyle, P. A. et al. White matter hyperintensities, incident mild cognitive impairment, and cognitive decline in old age. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 3(10), 791–800. https://doi.org/10.1002/ACN3.343 (2016).

Kloppenborg, R. P., Nederkoorn, P. J., Geerlings, M. I. & Van Den Berg, E. Presence and progression of white matter hyperintensities and cognition. Neurology 82(23), 2127–2138. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000000505 (2014).

Mok, V. et al. Predictors for cognitive decline in patients with confluent white matter hyperintensities. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 8(SUPPL. 5), S96–S103. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JALZ.2011.10.004 (2012).

Wang, Y. L. et al. Associations of white matter hyperintensities with cognitive decline: A longitudinal study. J.Alzheimer’s Dis. 73(2), 759–768. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-191005 (2020).

Tosto, G., Zimmerman, M. E., Hamilton, J. L., Carmichael, O. T. & Brickman, A. M. The effect of white matter hyperintensities on neurodegeneration in mild cognitive impairment. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 11(12), 1510–1519. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JALZ.2015.05.014 (2015).

Miao, R., Chen, H. Y., Robert, P., Smith, E. E. & Ismail, Z. White matter hyperintensities and mild behavioural impairment: Findings from the MEMENTO Study. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 17(S6), e053142. https://doi.org/10.1002/ALZ.053142 (2021).

Arvanitakis, Z. et al. Association of white matter hyperintensities and gray matter volume with cognition in older individuals without cognitive impairment. Brain Struct Funct. 221(4), 2135–2146. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00429-015-1034-7/FIGURES/3 (2016).

Hedden, T. et al. Cognitive profile of amyloid burden and white matter hyperintensities in cognitively normal older adults. J. Neurosci. 32(46), 16233–16242. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2462-12.2012 (2012).

Tullberg, M. et al. White matter lesions impair frontal lobe function regardless of their location. Neurology 63(2), 246–253. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.WNL.0000130530.55104.B5 (2004).

de Groot, J. C. et al. Cerebral white matter lesions and subjective cognitive dysfunction: The rotterdam scan study. Neurology 56(11), 1539–1545 (2001).

Pantoni, L., Poggesi, A. & Inzitari, D. The relation between white-matter lesions and cognition. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 20(4), 390–397 (2007).

Silbert, L. C. et al. Trajectory of white matter hyperintensity burden preceding mild cognitive impairment. Neurology 79(8), 741–747. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0B013E3182661F2B (2012).

Tosto, G., Zimmerman, M. E., Carmichael, O. T. & Brickman, A. M. Predicting aggressive decline in mild cognitive impairment: The importance of white matter hyperintensities. JAMA Neurol. 71(7), 872–877. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMANEUROL.2014.667 (2014).

Brickman, A. M. et al. Regional white matter hyperintensity volume, not hippocampal atrophy, predicts incident alzheimer disease in the community. Arch. Neurol. 69(12), 1621–1627. https://doi.org/10.1001/ARCHNEUROL.2012.1527 (2012).

Debette, S. et al. Association of MRI markers of vascular brain injury with incident stroke, mild cognitive impairment, dementia, and mortality: The framingham offspring study. Stroke 41(4), 600–606. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.570044 (2010).

Kuller, L. H. et al. Risk factors for dementia in the cardiovascular health cognition study. Neuroepidemiology 22(1), 13–22. https://doi.org/10.1159/000067109 (2003).

Prins, N. D. et al. Cerebral white matter lesions and the risk of dementia. Arch. Neurol. 61(10), 1531–1534. https://doi.org/10.1001/ARCHNEUR.61.10.1531 (2004).

West, N. A. et al. Neuroimaging findings in midlife and risk of late-life dementia over 20 years of follow-up. Neurology 92(9), e917–e923. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000006989 (2019).

Garde, E., Lykke Mortensen, E., Rostrup, E. & Paulson, O. B. Decline in intelligence is associated with progression in white matter hyperintensity volume. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 76(9), 1289–1291. https://doi.org/10.1136/JNNP.2004.055905 (2005).

Huynh, K. et al. Clinical and biological correlates of white matter hyperintensities in patients with behavioral-variant frontotemporal dementia and alzheimer disease. Neurology 96(13), e1743–e1754. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000011638 (2021).

García-Alberca, J. M., Garcia-Casares, N. & Royo, J. L. White matter lesions and hippocampal atrophy are associated with cognitive and behavioral and psychological symptoms in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and hypertension. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 17, e054134. https://doi.org/10.1002/ALZ.054134 (2021).

Brickman, A. M. et al. Reconsidering harbingers of dementia: progression of parietal lobe white matter hyperintensities predicts Alzheimer’s disease incidence. Neurobiol. Aging. 36(1), 27–32. https://doi.org/10.7916/54TE-WP27 (2015).

Yoshita, M. et al. Extent and distribution of white matter hyperintensities in normal aging, MCI, and AD. Neurology 67(12), 2192–2198. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.WNL.0000249119.95747.1F (2006).

Julayanont, P., Brousseau, M., Chertkow, H., Phillips, N. & Nasreddine, Z. S. Montreal cognitive assessment memory index score (MoCA-MIS) as a predictor of conversion from mild cognitive impairment to alzheimer’s disease. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 62(4), 679–684. https://doi.org/10.1111/JGS.12742 (2014).

Newman-Norlund RD, Newman-Norlund SE, Sayers S, et al. the aging brain cohort (ABC) repository: The university of south carolina’s multimodal lifespan database for studying the relationship between the brain, cognition, genetics and behavior in healthy aging. Neuroimage: Reports. 1(1):100008. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.YNIRP.2021.100008 2021

Nasreddine, Z. S. et al. The montreal cognitive assessment, MoCA: A Brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 53(4), 695–699. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1532-5415.2005.53221.X (2005).

Weintraub, S. et al. Version 3 of the alzheimer disease centers’ neuropsychological test battery in the uniform data set (UDS). Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 32(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.1097/WAD.0000000000000223 (2018).

Wardlaw, J. M. et al. Neuroimaging standards for research into small vessel disease and its contribution to ageing and neurodegeneration. Lancet Neurol. 12(8), 822–838 (2013).

Ashburner, J. & Friston, K. J. Unified segmentation. Neuroimage 26(3), 839–851 (2005).

Yeh, F. C. Population-based tract-to-region connectome of the human brain and its hierarchical topology. Nat. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41467-022-32595-4 (2022).

Alexander, D. C., Pierpaoli, C., Basser, P. J. & Gee, J. C. Spatial transformations of diffusion tensor magnetic resonance images. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 20(11), 1131–1139. https://doi.org/10.1109/42.963816 (2001).

Sachdev, P., Wen, W., DeCarli, C. & Harvey, D. Should we distinguish between periventricular and deep white matter hyperintensities? [4] (multiple letters). Stroke 36(11), 2342–2344. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.0000185694.52347.6e (2005).

Chen, H. F. et al. Microstructural disruption of the right inferior fronto-occipital and inferior longitudinal fasciculus contributes to WMH-related cognitive impairment. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 26(5), 576–588. https://doi.org/10.1111/CNS.13283 (2020).

Robertson, I. H. A right hemisphere role in cognitive reserve. Neurobiol. Aging. 35(6), 1375–1385. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.NEUROBIOLAGING.2013.11.028 (2014).

Rizvi, B. et al. Tract-defined regional white matter hyperintensities and memory. Neuroimage Clin. 25, 102143. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.NICL.2019.102143 (2020).

Duffau, H. Stimulation mapping of white matter tracts to study brain functional connectivity. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 11(5), 255–265. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2015.51 (2015).

Friederici, A. D. Pathways to language: Fiber tracts in the human brain. Trends Cogn. Sci. 13(4), 175–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2009.01.001 (2009).

Thiebaut de Schotten, M., Dell’Acqua, F., Valabregue, R. & Catani, M. Monkey to human comparative anatomy of the frontal lobe association tracts. Cortex 48(1), 82–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CORTEX.2011.10.001 (2012).

Juan, S. M. A. & Adlard, P. A. Ageing and cognition. Subcell Biochem. 91, 107–122. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-3681-2_5/COVER (2019).

Grady, C. L. & Craik, F. I. Changes in memory processing with age. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 10(2), 224–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-4388(00)00073-8 (2000).

Murman, D. L. The impact of age on cognition. Semin. Hear. 36(03), 111–121. https://doi.org/10.1055/S-0035-1555115 (2015).

Di Paola, M., Spalletta, G. & Caltagirone, C. In vivo structural neuroanatomy of corpus callosum in alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment using different mri techniques: A review. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 20(1), 67–95. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-2010-1370 (2010).

Wang, X. D. et al. Corpus callosum atrophy associated with the degree of cognitive decline in patients with Alzheimer’s dementia or mild cognitive impairment: A meta-analysis of the region of interest structural imaging studies. J Psychiatr Res. 63, 10–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JPSYCHIRES.2015.02.005 (2015).

Pedro, T. et al. Volumetric brain changes in thalamus, corpus callosum and medial temporal structures: Mild alzheimer’s disease compared with amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 34(3–4), 149–155. https://doi.org/10.1159/000342118 (2012).

Jokinen, H. et al. Corpus callosum atrophy is associated with mental slowing and executive deficits in subjects with age-related white matter hyperintensities: The LADIS Study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 78(5), 491–496. https://doi.org/10.1136/JNNP.2006.096792 (2007).

Qiu, Y. et al. Loss of integrity of corpus callosum white matter hyperintensity penumbra predicts cognitive decline in patients with subcortical vascular mild cognitive impairment. Front. Aging Neurosci. 13, 605900. https://doi.org/10.3389/FNAGI.2021.605900/BIBTEX (2021).

Liu, Y. et al. White matter hyperintensities induce distal deficits in the connected fibers. Hum. Brain Mapp. 42(6), 1910–1919. https://doi.org/10.1002/HBM.25338 (2021).

Bernal, B. & Altman, N. The connectivity of the superior longitudinal fasciculus: A tractography DTI study. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 28(2), 217–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.MRI.2009.07.008 (2010).

Forkel, S. J. et al. Anatomical predictors of aphasia recovery: A tractography study of bilateral perisylvian language networks. Brain 137(7), 2027–2039. https://doi.org/10.1093/BRAIN/AWU113s (2014).

Zhong, A. J., Baldo, J. V., Dronkers, N. F. & Ivanova, M. V. The unique role of the frontal aslant tract in speech and language processing. Neuroimage Clin. 34, 103020. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.NICL.2022.103020 (2022).

Rizio, A. A. & Diaz, M. T. Language, aging, and cognition: frontal aslant tract and superior longitudinal fasciculus contribute toward working memory performance in older adults. NeuroReport 27(9), 689–693. https://doi.org/10.1097/WNR.0000000000000597 (2016).

Taylor, A. N. W. et al. Tract-specific white matter hyperintensities disrupt neural network function in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 13(3), 225–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JALZ.2016.06.2358 (2017).

Stone, D. B., Ryman, S. G., Hartman, A. P., Wertz, C. J. & Vakhtin, A. A. Specific white matter tracts and diffusion properties predict conversion from mild cognitive impairment to alzheimer’s disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 13, 711579. https://doi.org/10.3389/FNAGI.2021.711579/BIBTEX (2021).

Jiménez-Balado, J., Corlier, F., Habeck, C., Stern, Y. & Eich, T. Effects of white matter hyperintensities distribution and clustering on late-life cognitive impairment. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-06019-8 (2022).

Funding

University of South Carolina Excellence Initiative, Aging Brain Cohort (ABC) Project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NB conceptualized project, conducted the data analysis, data organisation, wrote the main manuscript and prepared all figures, JW conceptualized project, conducted data analysis, data organisation, prepared figures, RNN preprocessed and organized neuroimaging data, SNN collected and organized behavioral data, SW collected and organized behavioral data, NR collected and preprocessed behavioral and neuroimaging data, AT preprocessed neuroimaging data, RWR organized data, LB reviewed manuscript, CR collected and preprocessed neuroimaging data, JF conceptualized project and obtained funding, LB conceptualized project, prepared figures. All authors reviewed manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

All participants gave informed consent for study participation and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Busby, N., Wilmskoetter, J., Newman-Norlund, R. et al. Damage to white matter networks resulting from small vessel disease and the effects on cognitive function. Sci Rep 15, 27736 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13813-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13813-7