Abstract

Sagittally unstable intertrochanteric fracture (SUITF) is the posterior displacement of the shaft fragment (posterior sagging, [PS]) which causes difficulty in achieving an acceptable closed reduction in lateral view. This study aimed to validate the morphological characteristics of SUITF. Data of patients with acute intertrochanteric fractures who underwent surgery were retrospectively reviewed. Altogether, 382 patients were enrolled and classified into the PS and control groups, based on the presence of PS. We obtained morphological characteristics on plain radiographs based on literature (Long medial beak, anterosuperior obliquity, lesser trochanter (LT) detachment, extramedullary beak, and V shape cortical defect). Comparison between groups and multivariable analysis were performed using a multiple Firth logistic regression analysis. For all morphological characteristics, the proportion of patients was significantly higher in the PS group than in the control group. In the multiple Firth logistic regression analysis, ‘long medial beak distal to lesser trochanter (LT)’ (OR, 7.93; 95%CI: 1.72–36.59; P = 0.008); ‘anterosuperior obliquity’ (OR, 23.87; 95%CI: 1.37–415.54; P = 0.030); ‘LT detachment,’ (OR, 10.15; 95%CI: 2.03–50.83; P = 0.005); and ‘extramedullary beak’ (OR, 39.47; 95%CI: 2.14–727.26; P = 0.013) were significantly associated with PS presence. These morphological characteristics will be helpful in preoperative detection of SUITF for direct manipulation of fractures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Closed reduction with traction on the fracture table, followed by internal fixation, can manage intertrochanteric fractures (ITFs) in most cases1. Gadegone et al. reported that 86% of ITFs were reduced using closed means2. However, some cases cannot be reduced in a closed manner and a higher incidence of complications exists in poorly reduced ITFs3,4. One of the typical displacements of ITFs is the proximal fragment, which is displaced posteriorly after closed reduction. Displacement in this typical direction can cause excessive collapse of the proximal fragment even if the amount of displacement is minimal. Thus, Carr emphasized bone-to-bone contact of both the anterior and medial cortices to prevent excessive collapse of the fracture site5. By placing the proximal fragment in the extramedullary position, initial stability is achieved in the coronal and sagittal planes, resulting in a lower probability of excessive sliding.

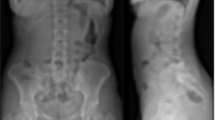

Contrary to the typical ITF, sagittally unstable intertrochanteric fracture (SUITF) is a type of ITF in which the shaft fragment is highly displaced posteriorly. SUITF presents difficulty in achieving acceptable reduction in a closed manner in the lateral view6 (Fig. 1). In SUITF, sagittal malalignment with a fracture gap is excessively large to allow for in situ fixation. Thus, direct manipulation is required for reduction of this fracture pattern, and open or percutaneous reduction techniques have been reported for the same6,7. If SUITF can be detected preoperatively through radiographs, surgeons can envision a sequence of reductions preoperatively and prepare reduction tools or instruments to cope with sagittal malalignment.

Previous studies have separately described distinguishable fracture morphology for SUITF (Table 1)6,7,8,9,10. However, these studies provided only simple descriptions. A qualitative comparative analysis of the comprehensive fracture morphology of SUITF is yet to be conducted. A lack of comprehensive evaluation limits our understanding of SUITF and surgical preparation. Therefore, we aimed to statistically evaluate fracture morphology of SUITF. The null hypothesis of the present study was that SUITF and morphological characteristics did not demonstrate a relationship, as described previously. The purpose of present study was to validate the morphological characteristics of SUITF.

Materials and methods

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Korea University Guro Hospital (IRB No. K2024-3021-001). A waiver for written informed consent was granted. Data collection was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations issued by the committee.

Data of patients with acute ITF who underwent surgery between January 2017 and December 2020 at a single university hospital were retrospectively reviewed. Initially, 548 patients were included in this study. We excluded the patients who had AO/OTA type A3 fractures11 (n = 81), irreducible ITF12 (n = 13), nondisplaced ITF (n = 62), pathologic fractures (n = 5), previous fracture history at the intertrochanteric area (n = 1), and peri-implant fractures (n = 4). Finally, 382 patients were enrolled in this study. We classified patients into the posterior sagging (PS) and control groups according to the presence of PS (described below and Fig. 1).

Radiographic measurements

The morphological characteristics of SUITF were evaluated using preoperative radiographs and computed tomography (CT) scans based on the descriptions proposed by Chun et al.6Sharma et al.7Zhang et al.8Hao et al.9and Li et al.10 (Table 1).

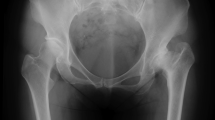

Long medial beak

For assessment of ‘long medial beak on the proximal fragment in anteroposterior (AP) view’6,7,8,10we set a criterion for beak length on AP view because no objective criteria for ‘long medial beak’ were established. Transverse lines were set to divide LT into one-third perpendicular to the femoral shaft axis. Patients with a medial beak distal to the distal one-third of the lesser trochanter (LT) were included. The second criterion was defined as the lower LT margin. If the medial beak was distal than two-third of the LT regardless of whether distal to the LT lower margin or not, it was assessed as ‘long medial beak distal to LT distal one-third.’ If the medial beak was distal than the lower margin of the LT, it was assessed as ‘long medial beak distal to LT lower margin.’ Patients with ‘long medial beak distal to LT lower margin’ were classified as having a ‘long medial beak distal to LT distal one-third,’ and were not separately grouped. Preoperative radiographs were obtained to measure medial beak length. Because the proximal fragment is commonly flexed and shortened in the AP view, we confirmed the relationship between the medial beak and lower margin of the LT using three-dimensional (3D) computed tomography (CT) (Fig. 2).

Radiograph and three-dimensional CT for long medial beak and displaced LT fragment. Transverse lines are set to divide the LT into one-third perpendicular to femur shaft axis (a, b). If the medial beak (asterisk) is distal than two-thirds of the LT (dotted line), it is assessed as ‘long medial beak distal to LT distal one-third.’ If the medial beak is distal than lower margin of LT (solid line), it is assessed as ‘long medial beak distal to LT lower margin.’ (a) In the anteroposterior radiograph, the medial beak is located within the LT distal one-third, and a completely fractured LT is noted. (b) When the view is reformatted considering the flexion of proximal fragment in the 3D CT scan, the medial beak is distal than the LT lower margin. We counted this case as ‘long medial beak distal to LT lower margin.’ (c) The LT fragment is placed along the proximal fragment which aggravated flexion deformity of the proximal fragment. CT, computed tomography; LT, lesser trochanter.

Anterosuperior obliquity

“Oblique fracture surfaces of distal fragments that face anterosuperiorly in the lateral view”6,8 were assessed in the hip translateral view (Fig. 3). We evaluated the obliquity of the fracture based on the distal fragments (anterosuperior) because the proximal fragment could have a flexion deformity with some external rotation in the SUITF. The angle of obliquity was not measured because it can change according to the angle of the translateral view.

Radiograph and three-dimensional (3D) CT for anterosuperior obliquity and extramedullary beak. (a) In the translateral view, oblique fracture surface of distal fragment for SUITF (white arrows) faces anterosuperiorly. (b) Fracture surface of typical intertrochanteric fractures faces posterosuperiorly (white arrows) restricting anterior displacement of proximal fragment. Medial (c) and lateral (d) views of the 3D CT scan for SUITF, sequentially. (c) Proximal fragment located at the extramedullary position appears shallow without a posterior cortex. (d) Contrary to the flexed anterior proximal fragment with a posterior fracture surface, the posterior coronal fragment is located next to the shaft fragment without malalignment.

CT, computed tomography; SUITF, sagittally unstable intertrochanteric fracture.

LT detachment

“Completely detached LT fragment or a part of proximal fragment”6,7 was assessed in hip AP view. Only LT fragment with complete fracture line was evaluated as “LT detachment.” If there was incomplete fracture line without displacement, it was not assessed as “LT detachment” (Fig. 2).

Extramedullary beak

“Medial spike of proximal fragment located in extramedullary position for shaft fragment”7 was assessed in both hip AP and hip translateral view. When proximal fragment was medial for shaft fragment in AP or anterior for shaft fragment in translateral view displacement of at least one cortex distance, it was assessed as “extramedullary” (Fig. 3).

V-shape defect

“V-shape cortical defect in the distal fragment on the externally rotation X-ray”8 was assessed in hip AP and external oblique view. A clear V-shape fracture margin on the shaft fragment was assessed as a “V-shape defect” (Fig. 4).

External rotation radiograph for a V-shape cortical defect. (a) A V-shape cortical defect (black arrow) is observed in the external rotation radiograph of a sagittally unstable intertrochanteric fracture. (b) Cortical defect from the medial beak (black arrow) is combined with the defect caused by the lesser trochanter fragment (black arrowhead), resulting in an ambiguous defect for assessment.

Subsequently, we evaluated shaft fragment PS using a C-arm image. All surgeries were performed using fracture tables. If there was a posterior displacement of shaft fragment for more than half of the neck diameter on the translateral view despite the traction, we assessed t phenomenon as ‘PS’ and the fracture as SUITF (Fig. 1).

Morphological characteristics were compared between the PS and control groups. A multivariable analysis was performed to assess the morphological characteristics associated with the presence of PS.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using the chi-square test for categorical variables and independent t-test for continuous variables. Continuous data were expressed as means and standard deviations. Simple and multiple Firth logistic regressions were conducted for the multivariable analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using R software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and SPSS version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Altogether, 119 patients (31.2%) had AO/OTA 31-A1 and 263 (68.8%) had AO/OTA 31-A2. Among them, 2 patients (1.7%) in the AO/OTA 31-A1 group and 24 patients (9.1%) in AO/OTA 31-A2 group presented with PS intraoperatively (P = 0.007). Thus, 26 patients were classified into the PS group, and 356 patients comprised the control group. No significant differences in age (80.73 ± 8.5 vs. 78.8 ± 11.3, P = 0.402) and laterality (58% vs. 45%, P = 0.229) were observed between the PS and control groups, respectively. The PS group had a higher proportion of female patients than the control group (88% vs. 70%, P = 0.050) (Table 2).

For all morphological characteristics, the proportion of patients was significantly higher in the PS group than in the control group (Table 3). In the multiple Firth logistic regression analysis, “long medial beak distal to LT lower margin” (odds ratio [OR], 7.93; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.72–36.59; P = 0.008); “anterosuperior obliquity” (OR, 23.87; 95% CI: 1.37–415.54; P = 0.030); “LT detachment” (OR, 10.15; 95% CI: 2.03–50.83; P = 0.005); and “extramedullary beak” (OR, 39.47; 95% CI: 2.14–727.26; P = 0.013) were significantly associated with the presence of PS (Table 4).

Discussion

In general, excessive sliding and varus collapse mainly cause ITF failure, and anterior and medial cortical support has been addressed in the literature5. Posteriorly displaced proximal fragments, which can be expressed as subtype P or intramedullary are considered risk factors for excessive sliding13. However, SUITF positioned as anteriorly displaced or flexed proximal fragments can demonstrate different problems. Compared with coronal plane reduction, which requires control of the varus or valgus alignment of the proximal fragment, the deforming force for SUITF is tremendous in the sagittal plane owing to anterior soft tissue pulling on the proximal fragment and PS caused by gravity on the shaft fragment. Thus, additional surgical intervention—such as the percutaneous Steinmann pin technique, anterior–posterior Hohmann retractor technique, leverage technique, cerclage clamping, cerclage wiring, anterior plating, and provisional pin fixation—is required (Supplemental material)6,7,14,15,16. Moreover, fracture reduction loss intraoperatively is likely due to difficulty of maintaining reduction. Even with appropriate reduction and implantation, secondary reduction loss with rotation of the proximal fragment can occur owing to a high deforming force (Fig. 5). If the SUITF was fixed with unacceptable reduction without appropriate bone-to-bone contact, it can result in highly increased anteversion, anterior apex angulation, and lateral protrusion of the lag screw.

Difficulties of SUITF. (a) SUITF is reduced and temporarily fixed with a 2.8-mm Steinmann pin. However, reduction loss is observed after intramedullary nailing. (b) Postoperative radiographs of the SUITF with cerclage wiring. (c) Two weeks postoperatively, reduction loss is observed. The lateral end of the blade is pulled into the medullary canal (white arrowhead) because of the high posterior sagging force of the shaft fragment. SUITF, sagittally unstable intertrochanteric fracture.

This study is clinically relevant because it enables preoperative detection of SUITF using statistically validated characteristics (long medial beak, displaced LT, anterosuperior obliquity, and extramedullary position). Unlike previous studies that simply list fracture morphology, this is the first study to statistically analyze these morphological characteristics. In addition, it could result in two benefits. First, the surgeon can better prepare to reduce the non-typical ITF. From percutaneous to open procedures, direct manipulation is usually needed, during which the deforming force, which is opposite to typical ITF, needs to be resisted. Second, these findings can optimize anesthesia preparation to account for potential bleeding and prolonged surgical time associated with open reduction6. With thorough preparation, reduction outcome can be improved and sufficient stability might be obtained. This, in turn, might allow prompt weight-bearing and guarantees fracture healing.

Of the 382 fractures, 26 (6.8%) patients in the present study demonstrated PS of the shaft fragments. Since we excluded several fracture types during patient enrollment, this should not be interpreted as the actual frequency of SUITF. Patients with a classic type of irreducible fracture with a long medial beak caught between the iliopsoas and LT were excluded12. Moreover, AO/OTA A3 type was excluded because of its inherent instability of this fracture type. PS was observed mainly in the incompetent lateral wall (AO/OTA A2 type) group (92%). As the lateral wall is attached to the gluteus and vastus lateralis, separation of the lateral wall from the shaft fragment indicates a loss of muscle stabilization.

Ikuta et al. analyzed fracture patterns that were irreducible in a closed manner according to preoperative radiographs using the position of the proximal fragment in the lateral view17. In that study, SUITF was included as subtype A, which is similar to the ‘extramedullary’ in the present study. In subtype A, they emphasized that displacement of the LT fragment contributed to irreducible fractures, in which the LT fragment was placed along the proximal fragment (Fig. 2). We also identified cases with SUITF morphology with an intact LT fragment demonstrating less prominent sagging of the shaft fragment owing to the pulling of the iliopsoas.

In the initial comparison, all the morphological characteristics were more common in the PS group. In the logistic regression analysis, a ‘long medial beak distal to the LT distal one-third’ and a ‘V-shaped defect’ did not demonstrate a significant association with PS. These two characteristics should be interpreted differently. For long medial beak, specific criteria for beak length were not proposed in the literature regarding SUITF, despite being mentioned6,7,8,17. Thus, we created two sets of criteria for verifying the length of the long medial beak; longer medial beak (distal to the LT lower margin) demonstrated a significant association in the regression analysis. However, in the present study, the lower margin distal to the LT had only 50% SUITF, and at one-third distal to the LT distal one-third which contained 92% SUITF is more appropriate as a criterion for long medial beaks in terms of preoperative detection. Notably, a longer medial beak was associated with a higher possibility of PS (31% vs. 15%). Empirically, the longer the proximal fragment the greater was the observed displacement, and PS was strongly predicted in this case. Although a longer medial beak length is strongly associated with PS, for preoperative detection, more attention should be paid to the length of the medial beak around the LT distal one-third. We presume that a pulling force is exerted by the iliofemoral ligament on the proximal fragment, which is attached to the intertrochanteric line18. ITF with a fracture line medial or proximal to the iliofemoral ligament can spontaneously realign during traction with the effect of ligamentotaxis. In contrast, the long medial beak of the SUITF containing the iliofemoral ligament attachment was pulled from the hip joint, aggravating the PS.

V-shaped cortical defects were not significantly associated with PS. Although cortical defects made from the medial beak could be detected in the external rotation view, they were often combined with defects caused by LT fragments, resulting in ambiguous assessment of defects (Fig. 4). As less than half of the patients in the PS group (39%) presented with a V-shaped cortical defect, it could not be used for preoperative detection.

In typical ITF, the proximal fragments consist of the head and coronal fragments with posterior soft tissue attachments19. In SUITF, the anterosuperior fracture line in the lateral view formed a shallow anterior proximal fragment with a posterior surface and no soft tissue attachment but a fracture surface (Fig. 3). Consequently, the posterior soft tissue could not stabilize the proximal fragment, resulting in marked flexion or anterior displacement. Moreover, the direction of the fracture plane itself cannot prevent displacement of the proximal fragment, and extramedullary beaks are likely to occur naturally. When the proximal fragment is intramedullary, cancellous bone impaction may occur; however, damage to the surrounding soft tissue tends to be minor. In contrast, the extramedullary position may occur with a burst of the surrounding soft tissue. Especially, soft tissue continuity at the end of the proximal beak may be completely lost, resulting in a flexion deformity of the proximal fragment.

In the PS group, all the patients were aged > 70 years, except for one young adult who was 46 years old and injured from high-energy trauma. Considering that most ITF occur as fragility fractures in the elderly, the PS group being mostly comprised by elderly individuals is plausible. However, in only one young patient, PS appeared when morphologic characteristics were present. Regardless of age and fragility fractures, PS can occur when morphological conditions are met, which is suitable for preoperative detection.

This study had several limitations. First, a relatively small number of patients with PS were included, although the statistical analysis revealed a significant association. Conversely, the number of patients in the control group was relatively large. This is because we collected data on all intertrochanteric fractures from 2017 to 2020. To overcome the limitation of a relatively small number of SUITF cases, we collected data on a large number of ITF cases to ensure a sufficient sample size of SUITF cases could be obtained. These factors might affect the generalizability of our findings. Second, the clinical outcomes of the enrolled patients were not evaluated. Since we focused on morphological characteristics for preoperative detection, a comparison of clinical results depending on preoperative detection and preparation would be meaningful. Third, although we assessed each morphological characteristic dichotomously, each factor had quantitative differences in morphology. Lastly, the causative effect of each characteristic on PS was not revealed. Therefore, a study based on soft tissue attachment using MRI findings or finite element analysis is needed.

Future studies should aim to include a larger number of SUITF cases to achieve statistical power and generalizability. It is also essential to analyze how each morphological characteristics of SUITF contribute to specific deforming forces and cause specific types of displacement. These findings indicate that it might be possible to individualize these reduction methods to resist specific deforming forces. Furthermore, comparative analysis of clinical outcomes between SUITF and typical ITF cases are necessary to highlight the clinical significance of SUITF and guide optimized treatment strategies.

In conclusion, long medial beak, anterosuperior obliquity in the lateral view, completely detached LT fragment, and extramedullary beak of the proximal fragment were significantly associated with PS of the shaft fragment. These morphological characteristics will be helpful in preoperative detection of SUITF for direct manipulation of the fracture.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Bannister, G. C., Gibson, A. G., Ackroyd, C. E. & Newman, J. H. The closed reduction of trochanteric fractures. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 72, 317 (1990).

Gadegone, W. M. & Salphale, Y. S. Proximal femoral nail - an analysis of 100 cases of proximal femoral fractures with an average follow up of 1 year. Int. Orthop. 31, 403–408 (2007).

Lim, E. J. et al. Comparison of sliding distance of lag screw and nonunion rate according to anteromedial cortical support in intertrochanteric fracture fixation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Injury 52, 2787–2794 (2021).

Hoffmann, M. F., Khoriaty, J. D., Sietsema, D. L. & Jones, C. B. Outcome of intramedullary nailing treatment for intertrochanteric femoral fractures. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 14, 360 (2019).

Carr, J. B. The anterior and medial reduction of intertrochanteric fractures: a simple method to obtain a stable reduction. J. Orthop. Trauma. 21, 485–489 (2007).

Chun, Y. S., Oh, H., Cho, Y. J. & Rhyu, K. H. Technique and early results of percutaneous reduction of sagittally unstable intertrochateric fractures. Clin. Orthop. Surg. 3, 217–224 (2011).

Sharma, G. et al. Pertrochanteric fractures (AO/OTA 31-A1 and A2) not amenable to closed reduction: causes of irreducibility. Injury 45, 1950–1957 (2014).

Zhang, S., Zhang, J. Y., Yang, D. M., Yang, M. & Zhang, P. X. Morphology character and reduction methods of sagittally unstable intertrochanteric fractures. Beijing Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 49, 236–241 (2017).

Hao, Y. et al. Trochanteric and subtrochanteric fractures irreducible by closed reduction: a retrospective study. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 18, 141 (2023).

Li, K., Du, X., Chen, Z. & Shui, W. Minimally invasive reduction of irreducible, sagittally unstable peritrochanteric fractures: novel technique and early results. Chin J. Traumatol (2024).

Meinberg, E. G., Agel, J., Roberts, C. S., Karam, M. D. & Kellam, J. F. Fracture and dislocation classification Compendium-2018. J. Orthop. Trauma. 32 (Suppl 1), S1–s170 (2018).

Said, G. Z., Farouk, O. & Said, H. G. An irreducible variant of intertrochanteric fractures: a technique for open reduction. Injury 36, 871–874 (2005).

Yoon, Y. C., Oh, C. W., Sim, J. A. & Oh, J. K. Intraoperative assessment of reduction quality during nail fixation of intertrochanteric fractures. Injury 51, 400–406 (2020).

Cho, J. W. et al. Provisional pin fixation can maintain reduction in A3 intertrochanteric fractures. Arch. Orthop. Trauma. Surg. 136, 945–955 (2016).

Kim, Y. et al. Hook leverage technique for reduction of intertrochanteric fracture. Injury 45, 1006–1010 (2014).

Lim, E. J. et al. Surgical outcomes of minimally invasive cerclage clamping technique using a pointed reduction clamp for reduction of nonisthmal femoral shaft fractures. Injury 52, 1897–1902 (2021).

Ikuta, Y., Nagata, Y. & Iwasaki, Y. Preoperative radiographic features of trochanteric fractures irreducible by closed reduction. Injury 50, 2014–2021 (2019).

Wagner, F. V. et al. Capsular ligaments of the hip: anatomic, histologic, and positional study in cadaveric specimens with MR arthrography. Radiology 263, 189–198 (2012).

Cho, J. W. et al. Fracture morphology of AO/OTA 31-A trochanteric fractures: A 3D CT study with an emphasis on coronal fragments. Injury 48, 277–284 (2017).

Funding

This work was supported by the research grant of the Chungbuk National University in 2023.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EJL have drafted the work and analyzed statistically. JSK acquired radiographic data. H-CS interpreted the analyzed data. YKR acquired the patients data. JSC visualized analyzed data. J-KO supervised the process of data acquisition and analyze. WC and J-WC have the conception, designed the work, and substantively revised the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lim, E.J., Kim, J.S., Shon, HC. et al. Predicting ‘sagittally unstable intertrochanteric fractures’ that require direct manipulation for reduction: a fracture morphology analysis. Sci Rep 15, 28932 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14043-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14043-7