Abstract

This study investigates the fundamental frictional behavior of granules through experimental analysis under two direct-shear testing scenarios: grains-assembly shearing and grains-to-surface shearing (when the shear plane is between the grains and a flat solid surface), incorporating new experimental data with comparison to previous findings. By varying grain mineralogy, morphology, and pore liquids, we identify key differences between the two systems. The results show that grain-assembly friction is influenced by grain morphology but not by mineralogy, whereas grains-to-surface friction exhibits the opposite trend. The presence of pore liquid also has contrasting effects: it reduces friction in grain-assemblies due to lubrication but increases friction of grains-surface systems due to solid-liquid adhesion. This paper explains these trends by hypothesizing a link between each shearing scenario to distinct grain displacement mechanisms—particle sliding or rolling (rearrangement). It also shows that the friction of an ‘ideal’ granular system, made of uniform, rigid, and smooth spheres, sets a threshold for the effects of lubrication and adhesion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Granular materials, ranging from aggregates to sands and powders, present a fascinating challenge at the intersection of physics, mechanics, and materials science1,2. Assemblies of these discrete particles ubiquitous in natural environments and engineering systems, exhibit complex behaviors that often defy traditional classifications such as solids, liquids, or gases1,3. The mechanical behavior of these materials is dictated by the intricate interplay between the particles themselves and their interactions with the fluids that occupy the space between them4,5. This complexity is sparking intense scientific and engineering interest in uncovering the fundamental principles that govern the mechanics of granular systems3,6.

The field of soil mechanics pioneered the understanding of the mechanical behavior of granular materials, particularly in the context of water-saturated soils7,8. The principle of effective stress, relating soil strength and deformation to pore water pressure, is a cornerstone of analyzing the behavior of these soils9,10. However, water-saturated soils represent only one scenario in a vast spectrum of solid-liquid combinations possible, which can lead to various mechanical phenomena11,12. For example, oil occupancy in the soil pore space tends to reduce the friction resistance of sandy soils due to the lubrication effect, while in clayey soils, it tends to increase the friction resistance due to physical-chemical interactions13,14. Such composite solid-liquid effects add to the mechanical complexity inherent in the granular structure, including the chaotic arrangement, morphology, and mineralogy of granules within the assembly15,16,17.

While traditionally granular material is characterized through the lens of continuum mechanics, by bulk properties such as strength and stiffness that describe the behavior of the entire assembly, a complementary perspective requires looking at the intergranular kinematics18,19. The unique displacement patterns at the particle level are fundamentally related to macro-scale phenomena such as the compressibility, dilatancy, and shear resistance of the granular assembly. Grain morphology characteristics, such as grain shape, angularity, and surface texture, impose kinematic constraints that affect the particle motion, the force transfer patterns, and the grain interlocking during the particles rearrangement20,21,22. For example, rounder and smoother grains experience less interlocking, allowing them to easily move against each other20,23,24. A similar reduction in grain interlocking, and consequently in bulk friction, can also occur through the lubrication effect, in which a liquid layer reduces solid-to-solid contacts20,24,25.

Various approaches have been employed to examine granular system behavior and grain-level interactions and properties. Miron et al. (2023) conducted a study on the effect of adhesive liquids on the shear strength of granular samples, utilizing a Centrifugal Adhesion Balance system26, which is designed to measure microscale adhesion forces between liquids and solids27,28. The study concluded that shear strength increases proportionally with the solid-liquid work of adhesion. In a subsequent investigation, Miron et al. (2025) explored the influence of oil lubrication on the frictional properties of granular soils, with a specific emphasis on grain morphology and liquid viscosity24. Through direct-shear testing of quartz samples with varying grain morphologies and pore oils, the study formulated the lubrication effect expression based on dry sample friction and oil viscosity, identifying a unique friction threshold that remains unaffected by lubrication. Dai et al. (2015) suggested that lubricant-induced friction reduction results from reduced interparticle friction29, which is associated with the ‘true’ friction between mineral surfaces30. Direct measurement of interparticle friction is challenging, with Rowe (1962) being one of the first to propose addressing it by shearing grains across a smooth surface made of the same material30, showing that different minerals are associated with different grains-to-surface shear resistance. Later, Skinner (1969) illustrated that the grains-to-surface shear scenario provides insights into grain displacement mechanisms, such as grains rolling or sliding. Notably, the transition between these two mechanisms was found to depend on the presence of pore liquid31.

This paper examines the complex interplay between grain mineralogy, morphology, and the influence of pore liquids on frictional behavior through an empirical study of two distinct shearing scenarios: grains-to-surface and grains-assembly shearing. The study reveals opposing fundamental trends in the frictional responses of these two systems, influenced by these factors, and attribute these differences to variations in grain displacement mechanisms unique to each system. The paper proposes a general framework through which the frictional responses of both systems can be uniformly described.

Experimental study

Grains-to-surface and grains-assembly shear experiments were conducted to identify the key factors governing the behavior of granular systems. The shear response in each system is analyzed as a function of independent properties of the sample components, associated with both the solid and liquid properties. Specifically, the mineralogy of the grains is quantified by characterizing the surface roughness and the surface energy of the solid, the liquid that occupies the pore spaces of the granules is characterized by its dynamic viscosity, and the mechanical interaction between the solid and the liquid is characterized through the work of adhesion that gives expression to the forces of attraction between them. The investigation of examined solids and liquids and the experimental setups are detailed in the following sections.

Pore liquids

Four types of liquid are used in this study, including water and three types of oils: 15W40, 80W90, 20W50. These oils are known for their lubricating effect, which is attributed to their high dynamic viscosity24. The oils viscosities are evaluated in this study by a rotational rheometer test, which is based on rotating a liquid sample at varying angular velocities, \(\:\omega\:\), and measuring the resulting torque, \(\:T\), as illustrated schematically in Fig. 1a. The dynamic viscosity of the liquid, \(\:\eta\:\), is the ratio between the shear stress \(\:{\tau\:}_{L}\) and the shear strain rate\(\:\:\dot{\gamma\:}\), which are respectively related to \(\:T\) and \(\:\omega\:\), and to the geometry of the system, as shown in the figure. Figure 1b presents \(\:{\tau\:}_{L}\) against \(\:\dot{\gamma\:}\) for the tested oils at a temperature of 25 °C, along with the typical trend for water at this temperature. These results indicate a closely Newtonian behavior, where \(\:\eta\:\) (the slope of the trend) is independent of \(\:\dot{\gamma\:}\). Table 1 lists the viscosities values for the different liquids, labeled L1-L4, together with their densities,\(\:\:{\gamma\:}_{L}\), which were measured using a pycnometer test.

The granular assemblies

Granular materials differ from each other both in terms of grain morphology and mineralogy. In order to separate these two factors when examining the mechanical response, we use grains with similar morphology made of different materials and grains with the same material but different morphology. For the investigation of different minerals, ~ 1 mm round beads of glass, copper, stainless steel, and chromium, are used. For the investigation of different morphologies, we used both glass beads and natural quartz sand. Table 2 details the granule types examined in this study, labeled by S1-S5. The surface characteristics of minerals can be quantified through the surface energy, which is characterized in this work as described below.

Interfacial properties

Interfacial properties32,33,34 are known to impact the mechanical behavior of granular materials26. To explore the connection between interfacial properties and mechanical response, this work focuses on characterizing (1) the solid surface energy, \(\:{\gamma\:}_{SV}\) (for the “grain-vapor” interface), and (2) the solid-liquid work of adhesion, \(\:{W}_{SL}\) (for the grain-liquid interface). A brief overview of these surface energies is given below.

Solid surface energy, \(\:{\gamma\:}_{SV}\) –is the energy required to create a unit area of a new surface in a solid material32,33,34,35. Variations in solid surface energy reflect differences in surface interactions and though as an intensive property it is not influenced by surface texture, on an extensive level (i.e. not as per unit area but as part of the total energy in the system) it is. This study aims to link between solid surface energy and the mechanical response of granules associated with different minerals.

Solid-liquid work of adhesion, \(\:{W}_{SL}\)- is the energy required to separate solid and liquid at their interface, reflecting the strength of the adhesive forces between them27,32,33,34. Higher \(\:{W}_{SL}\) values indicate stronger adhesion, influencing how well the liquid spreads or adheres to the solid surface. This study aims to link this adhesion property to the effect of the pore-liquid interactions on the mechanical response of granular materials.

The relationship between \(\:{W}_{SL}\) and \(\:{\gamma\:}_{SV}\) is given by Young-Dupré Eq. (27):

where \(\:{\gamma\:}_{LV}\) is the surface energy of the liquid-vapor interface, also known as the liquid surface tension, and \(\:{\gamma\:}_{SL}\) is the solid-liquid interfacial energy. \(\:\theta\:\) is the contact angle between a liquid and a solid, representing the angle formed at the interface where the three phases—solid, liquid, and vapor—meet. It is important to note that the experimental evaluation of\(\:\:{W}_{SL}\) (Eq. 1) involves a three-phase system—solid, liquid, and vapor. Although our granular experimental setup consists of a two-phase configuration (solid–liquid), we adopt this measure as an indirect proxy for solid–liquid molecular interactions (e.g., van der Waals forces, polarity, or chemical affinity). This approach has also been previously employed by26 for saturated granular systems, and relating intermolecular forces to such wetting properties is considered in 35.

\(\:{W}_{SL}\) and \(\:{\gamma\:}_{SV}\) were estimated using Eq. 1, with the full calculation method detailed in the Supplementary Materials section. Estimating these properties involves determining the surface tension, \(\:{\gamma\:}_{LV}\), and the contact angle, \(\:\theta\:\), associated with the examined materials. \(\:{\gamma\:}_{LV}\) was measured using the “falling drop weight” method32, based on dripping drops from the end of a tube as described in Fig. 2a. \(\:{\gamma\:}_{LV}\) is the ratio between the weight of the drop just before it falls (as shown in the figure) and the tube’s circumference. \(\:\theta\:\) was measured between liquid droplets and smooth surfaces made of the same material as the tested grains, using high-resolution images as described in Fig. 2b. The experimentally determined \(\:{\gamma\:}_{LV}\) and \(\:\theta\:\) values for the materials supplied in Supplementary Materials section, along with the calculation for estimating \(\:{\gamma\:}_{SV}\) and \(\:{W}_{SL}\). Table 3 and 4 provide the results of \(\:{\gamma\:}_{SV}\) and \(\:{W}_{SL}\), respectively.

Surface roughness, \(\:{R}_{q}\)- is a widely used statistical metric that quantifies a material’s surface texture by measuring the standard deviation of height variations from the mean surface level. The \(\:{R}_{q}\) values for the different solids were evaluated using a Zygo NewView 200 white-light interferometric microscope equipped with a 50× Mirau objective. For each material (plates and spheres), 4–5 measurements were performed, presented in Table 5.

The shear response of granular systems

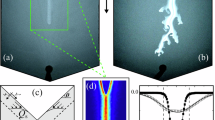

This study explores the shear response of granular samples through two test scenarios: grains-to-surface shearing and grains-assembly shearing, as illustrated in Fig. 3. In each scenario, various combinations of grains and liquids are tested (as detailed in previous sections) to induce mechanical reactions of differing intensities. The goal is to link these mechanical variations to properties of the sample components, such as liquid viscosity, solid surface energy, and the adhesive interactions between the liquid and the solid. Additionally, the study seeks to analyze grain movement mechanisms by comparing the shear behaviors between the two scenarios, thus providing deeper insights into how these factors influence granular mechanics.

Results and analysis

The results below are presented in terms of different variations of the friction angle property, \(\:\phi\:\), which is related to the ratio between the shear and the normal stress in the examined samples; \(\:\text{tan}\phi\:=\tau\:/\sigma\:\) (where \(\:\tau\:\) and \(\:\sigma\:\) are the shear and the normal stresses). The friction angle of granular samples is examined in this study in two shear scenarios described in Fig. 3: (a) grains-to-surface shearing and (b) grains-assembly. The shear tests were performed on both dry samples and liquid saturated samples. The samples were saturated in such amount which prevents the development of capillary forces (suction forces) in the pore space. The saturated samples were tested under fully drained conditions and at relatively slow shear rates to prevent the development of hydrostatic and viscous-shear stress, respectively.

Grains-to-surface shearing

The grains-to-surface shearing was investigated using the shear device illustrated in Fig. 3a. This testing approach has been previously employed to assess the friction angle between mineral surfaces, \(\:{\phi\:}_{\mu\:}\)30, characterizing the fundamental interparticle friction independent of kinematic constraints associated with grain morphologies. The distinction between the microscopic friction angle (\(\:{\phi\:}_{\mu\:}\)) and the macroscopic friction angle of the granular assembly has been extensively studied both experimentally and numerically (e.g., using DEM simulations). These studies consistently reveal a fundamental difference between the two, which depends strongly on particle shape and the dominant displacement mechanisms within the material29,31,36,37. The shear device (Fig. 3a) is composed of an upper 6 × 6 cm2 sample sheared against a smooth surface fixed at the bottom. The granular samples used for this study are S1-S3 and S5 (see Table 2), which refer to quartz sand and beads assemblies of different materials. The smooth surfaces used in the tests were made of the same material as the grains (a glass surface was used with both the glass beads and the quartz sand). A surface roughness meassurement procedure was employed to evaluate the surface roughness of both the grains and the plates (Table 5), confirming that the plates exhibit lower roughness values than the grains and can therefore be regarded as ‘smooth’ in the context of this study.

Figure 4 describe the grains-to-surface shearing results obtained for the dry samples. Figure 4a describes the developed shear stress during horizontal displacement under different normal stresses, for the various samples. The highlighted lines refer to the plateaued shear stress response after sufficient shearing. The plateaued shear stress response is described in Fig. 4b as a function of the applied normal stress. These results are described by linear trends, starting from the origin and inclined by \(\:{\phi\:}_{\mu\:}\) angle. As can be seen, \(\:{\phi\:}_{\mu\:}\) ranges from 6.6o to 9.7o, with the lowest value belonging to the glass beads sample (S1) and the highest to the stainless-steel beads sample (S3). Notably, the \(\:{\phi\:}_{\mu\:}\) value obtained for the quartz sand (S5) is similar to that of the glass beads sample (S1), which are both related to a quartz mineral despite their distinct grain morphologies (presented in the figure). This observation reinforces the fact that \(\:{\phi\:}_{\mu\:}\) values are inherently related to the mineral type rather than the grains morphology.

Grains-to-surface shear test results for different grain minerals and morphologies under dry conditions and varying levels of applied normal stress, σ. The results include: (a) shear stress, τ, against horizontal displacement, and (b) shear stress after sufficient shearing plotted against the applied σ.

Since \(\:{\phi\:}_{\mu\:}\) is directly influenced by the mineral type, a qualitative comparison can be made between \(\:{\phi\:}_{\mu\:}\)and the microscale surface characteristics associated with each mineral. Specifically: (1) surface roughness values (\(\:R{}_{q}\)), detailed in Table 5 and shown in Fig. 5a, exhibit a direct positive correlation with \(\:{\phi\:}_{\mu\:}\); and (2) solid surface energy values (\(\:{\gamma\:}_{SV}\)), presented in Table 2 and shown in Fig. 5b, also demonstrate a reasonable trend with \(\:{\phi\:}_{\mu\:}\) (The negative slope observed in this case may be attributed to the solid–liquid wetting characteristics, particularly the contact angle used in the current analysis, which is itself influenced by surface roughness33,38,39. Although Fig. 5 provides only a first-order approximation, based on a limited four-point dataset, the observed trends offer preliminary insight into the relationships between the parameters.

The same grains-to-surface sample compositions were examined when saturated with different liquids. The liquids used in these tests are L1-L3 (see Table 1), which are water and two types of oils. Figure 6 describes the converged shear stress obtained in these tests as a function of the applied normal stress, where the sub-figures a-c describe test results of different minerals. The inclination of the different trends expresses the grains-to-surface friction property in the presence of liquid, \(\:{\phi\:}_{\mu\:L}\), that is related to the specific solid-liquid combination. It can be seen that the low friction values are obtained for the dry samples regardless of the solid type, while the high values of \(\:{\phi\:}_{\mu\:L}\) are obtained for water (L1) saturated grains. The oil-saturated grains yield a slightly higher friction value than the dry samples (which may be counterintuitively since oils are typically associated with friction reduction due to the lubrication effect; this phenomenon will be discussed in detail later).

The previously observed similarity in \(\:{\phi\:}_{\mu\:}\) values under dry conditions for both glass beads and sand (Fig. 4) persists when these materials are introduced to the same liquid, as indicated by the green and yellow markers in Fig. 6a. This consistency reinforces our observation that grain-surface friction is strongly influenced by the mineral type of the grains, regardless of the grains’ morphology. The fact that \(\:{\phi\:}_{\mu\:L}\) can be described as a mechanical property related to the interaction between specific solid mineral and liquid combination, allows us to compare \(\:{\phi\:}_{\mu\:L}\) to other physical properties related to the interaction of the same mineral-liquid configurations.

Figure 7 illustrates the increase in friction due to the soil-liquid interaction, denoted as \(\:{\Delta\:}{\phi\:}_{SL}\), which represents the rise in \(\:{\phi\:}_{\mu\:L}\) compared to \(\:{\phi\:}_{\mu\:}\)values. Plotting \(\:{\Delta\:}{\phi\:}_{SL}\), against the work of adhesion, \(\:{W}_{SL}\) (as listed in Table 4), for the same solid-liquid configurations reveals a clear trend: \(\:{\Delta\:}{\phi\:}_{SL}\) significantly increases with higher \(\:{W}_{SL}\).

Grains-assembly

The grains-assembly shearing behavior was examined using a direct shear test device designed for 6 × 6 cm2 samples, illustrated in Fig. 3b. The study focuses on the critical friction angle, \(\:{\phi\:}_{c}\), that is independent on the volume change tendency during shearing12,30. The evaluation of \(\:{\phi\:}_{c}\) is determined based on the residual shear stress response, at which the volumetric change was reached to a constant value.

Let us first refer to the the friction in dry samples. Figure 8a provides an example of volumetric changes observed during horizontal displacement in glass beads samples (S1) under dry conditions. These samples exhibit volumetric compaction or dilation toward a volumetric change cessation, depending on the initial porosity state and the applied normal load. Correspondingly, Fig. 8b illustrates the shear stress response associated with these volumetric changes. The shear stress converges to a value corresponding to σ tan(\(\:{\phi\:}_{c}\)), as illustrated in Fig. 8c. In other words, the stress ratio τ/σ converges to a constant value at the residual stress response, represented by the inclination of \(\:{\phi\:}_{c}\).

Example of direct shear test results for glass beads under dry conditions and varying levels of applied normal stress, σ: (a) vertical displacement versus horizontal displacement, (b) shear stress response as a function of horizontal displacement, and (c) critical shear stresses plotted against the applied normal stress.

Rounded smooth particles

For the study of the mineral effect on the grains-assembly friction, a series of direct shear tests were performed on smooth beads assemblies, to reduce the effect of grains morphology on the friction results. Figure 9a-c show the stress ratio response, \(\:\tau\:/\sigma\:\), of samples composed of S2-S4 dry beads, against horizontal displacement. As can be seen, a similar critical stress ratios (corresponding to similar \(\:{\phi\:}_{c}\) values) were obtained for the different grain minerals (including S1 results shown in Fig. 8), with an average value of \(\:{\phi\:}_{c}=15.1^\circ\:\). This similarity is not intuitive since we obtained different \(\:{\phi\:}_{\mu\:}\) values for these materials (Fig. 4). In other words, it is noticeable that the interplay between the interparticle friction (\(\:{\phi\:}_{\mu\:}\)) and the sample-scale friction (\(\:{\phi\:}_{c}\)) is weak. We hypothesize that the difference between these two friction quantities is linked to the grains’ displacement mechanism, which is influenced by the specific system used for their evaluation, as will be discussed later.

To investigate the liquid effect on the bead samples (while still disregarding the influence of grain morphology), direct shear tests were performed on bead samples S1–S4 when saturated with liquids L1–L4. We define the critical friction property of saturated granular samples as \(\:{\phi\:}_{cL}\). Figure 10 presents the critical shear stress results obtained for various solid-liquid combinations as a function of the applied normal stress. Different solids are represented by distinct symbols, while pore liquids are indicated using different colors. The dashed line represents the average, \(\:{\phi\:}_{c}\), value of the dry bead assemblies (Fig. 9). As shown in the figure, the results for the different solid-liquid combinations closely align with this trend line, suggesting that the effect of liquids on the friction of smooth bead assemblies is negligible. Notably, the independence of \(\:{\phi\:}_{cL}\) from the liquid type (Fig. 10), contrasted with the clear dependence of \(\:{\phi\:}_{\mu\:L}\) on the liquid type (Fig. 6), highlights the weak interplay between interparticle friction, \(\:{\phi\:}_{\mu\:L}\), and sample-scale friction, \(\:{\phi\:}_{cL}\), in smooth solid granules when liquids are present.

Particles with a general morphology

Unlike the experimental study described above, the experimental study on particles with a general morphology (this section) builds on the findings of Miron et al. (2025)24. These findings complement the overall analysis of the current study and are therefore briefly summarized here.

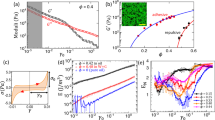

The results discussed above pertain to smooth spherical grains, representing only one specific instance within the vast spectrum of possible grain morphologies. Grain morphologies can vary in terms of shape, angularity, roughness, size distribution, etc., where it is well-known that these factors significantly affecting the mechanical response of the granular material. These factors are highly influenced by the presence of liquid. Figure 11 shows Miron et al. (2025)’s findings in terms of friction angles, illustrating the relationship between the critical friction of liquid-saturated quartz assemblages (with different grain configurations and liquid types) and their corresponding friction angle under dry conditions. The wide range of friction values was achieved by using various quartz morphologies; glass beads, sand, crushed glass, and some combinations of them. As can be seen from the figure, the water-saturated samples exhibit friction trends similar to the dry samples, whereas oil-saturated samples demonstrate comparatively reduced friction (\(\:{\phi\:}_{c}-{\phi\:}_{cL}\)) due to the lubrication effect. This friction reduction effect is intensified by two independent factors: (1) the increase in the liquid viscosity, and (2) the increase in the grain irregularity, that can be indirectly quantified by the resultant friction angle (\(\:{\phi\:}_{c}\)).

The linear trends shown in Fig. 11 represent \(\:{\phi\:}_{cL}\) associated with the different liquids, where it is evident that these trends converge as \(\:{\phi\:}_{c}\) decreases, ultimately intersecting at a specific friction value. This intersection point represents the threshold of the lubrication effect, at which \(\:{\phi\:}_{cL}\) equals \(\:{\phi\:}_{c}\), independent of the pore liquid. The lubrication threshold corresponds to the critical friction of an ‘ideal’ sample composed of uniform, smooth, and rigid spheres; such an ideal configuration yields the minimum friction value compared to any other grain morphology. The results presented in Fig. 10 support the friction threshold concept, demonstrating that the friction of near-ideal grain samples remains unaffected by the lubrication effect, regardless the grain minerals type.

The relationship between the critical friction of liquid-saturated samples, \(\:{\phi\:}_{cL},\) and their corresponding friction angle in a dry condition, \(\:{\phi\:}_{c}\) (digitized from Miron et al., (2025))24.

Discussion

The friction of grain systems is studied in this paper by facilitating two sets of experimental studies: grains-assembly shearing and grains-to-surface shearing. The difference between the mechanical response in these testing sets were examined in terms of their dry friction, the grain shape, the grain mineralogy, and the effect of solid-liquid interaction. Table 6 summarizes the essential differences of these effects between the two datasets. The table specifies the following differences: (1) the friction values under dry conditions of the grains-to-surface system are significantly lower than the entire friction spectrum obtained from the grains-assembly system. (2) The grains-to-surface friction is not sensitive to the grain morphology, as opposed to the high sensitivity to grain morphology in the grains-assembly system. (3) In contrast, the grains-assembly system found not sensitive to the grain mineral while the grains-to-surface friction is affected by the mineral type. (4) In the presence of liquids, an increased friction was observed in the grains-to-surface system (linked to adhesion effect) while a decrease in friction was observed in the grains-assembly system (linked to a lubrication effect). Practically speaking, the table summarizes the findings of the current experimental study on grain-to-surface shearing, alongside the experimental results published by Miron et al. (2025)24 on grain-assembly shearing.

These contrasting effects, specified in Table 6, are interpreted in this study based on the grain displacement mechanisms in the two systems, which result from either sliding or rolling patterns of the grains. Figure 12 demonstrates the fundamental difference between these displacement mechanisms, with respect to a schematical case of grains-surface shearing. The figure illustrates that a single grain tends to slide across a perfectly smooth surface without engaging in rolling. We anticipate a higher friction response when the grain slides against a rougher surface. However, beyond a certain roughness threshold, the grain is more likely to roll than slide. We hypothesize the same logic for adhesive surface, in which for a sufficient adhesive contant the grain would be more likely to roll. Once rolling governs the particle’s motion, this mechanism is insensitive to further increases in adhesive strength. In the case of multiple particle shearing upon a surface, the rolling mechanism derives an increase in the overall friction by causing adjacent grains to rub against each other, whereas the sliding mechanism is unaffected by the neighboring particles due to minimal interactions between them.

In contrast to the displacement mechanism proposed for grains sheared against a surface (Fig. 12), the mechanism in a grain assembly is governed by the degree of interlocking between grains, with a greater tendency for grains to roll as the interlocking decreases24. In other words, the addition of lubricants, which reduces the degree of interlocking, enhances the particle rolling mechanism within the system. In an attempt to combine our two sets of findings into an integrative description of the friction property in general granular assemblies, Fig. 13 presents both grains-assembly and grains-to-surface friction results, combining the data shown in Figs. 6 and 11. The figure marks five regions of interest, a – e, that are described below:

-

(a)

\(\:{\phi\:}_{c}\) for dry grains: a 1:1 line, which represents friction values of dry granular samples (or water-saturated samples), over a wide range of friction values associated with the examined grain morphologies.

-

(b)

Lubrication threshold: this term refers to the theoretical friction threshold for lubricated granular samples. As the degree of lubrication increases, friction in granular samples decreases due to reduced grain interlocking, reaching a point of maximum lubrication effect, which corresponds to a minimal (theoretical) friction threshold24.

-

(c)

The intersection point of the two friction regions, attributed to ‘ideal’ grain samples (composed of uniform, smooth, and rigid spheres), which can be defined as a reference case that independant of solid-liquid interaction.

-

(d)

\(\:{\phi\:}_{\mu\:}\) for dry grains: extending the 1:1 friction line for lower values associated with the grains-to-surface shearing scenario.

-

(e)

Adhesion threshold: From the grain-to-surface friction results marked in the figure, one can see that the higher the adhesion the greater the friction response, up to the point where a sufficient adhesion reaches the horizontal line in the figure. Based on the link made between this sufficient adhesion and rolling mechanism (Fig. 12), we hypothesize that horizontal line (c-e) may represent a frictional behavior dominated by a rolling mechanism.

Due to the fact that \(\:{\phi\:}_{\mu\:L}\) reaches a maximum threshold similar to the minimal threshold of \(\:{\phi\:}_{cL}\), both related to a grain-rolling mechanism, it seems that the horizontal line in the figure (b-c-e) has a general meaning of friction response that is dominated by grain rolling. We hypothesize that a steeper inclination of this line, anchored at point c, indicates a greater dominance of the grain sliding mechanism over the grain rolling mechanism. It should be noted that the illustrative scheme presented in Fig. 13 is based solely on macro-scale observations and is therefore intended as a conceptual hypothesis to guide future micro-scale investigations into grain-scale displacement mechanisms in granular systems.

Conclusions

In this study, we conducted shear experiments on granular materials under two distinct shear scenarios: grains-to-surface and grains-assembly shearing. The friction property derived from these testing was comprehensively studied by using samples of various grain minerals, grain morphologies, and different pore-liquids. The concluded key factors affecting the frictions in the two shear scenarios are:

-

1.

Granules mineralogy. While grains-assembly friction is unaffected by the grains mineralogy, grains-to-surface friction is affected by the grains mineral type depending on solid surface energy of the grains.

-

2.

Granules morphology. Grains with higher irregularity in morphology (i.e., shape, angularity, and roughness) significantly increase the friction within a grains assembly. However, in a grains-to-surface system, the friction is notably unaffected by these morphological variations. We believe this distinct difference between the two systems is related to the deformation mechanisms of the grains. Specifically, shearing against a smooth surface primarily involves grain sliding, whereas shearing within an assembly is largely influenced by particle rearrangement which is affected by the particles interlocking that directly linked to the grains’ morphology.

-

3.

Solid-liquid interaction. In the two shear scenarios, the presence of liquid has opposite effects. In a grains assembly, liquid reduces friction due to its lubrication effect, which is associated with the liquid’s viscosity and its impact on particle rearrangement. Conversely, when particles slide against a smooth surface, the liquid intensifies friction due to the solid-liquid work of adhesion.

It is demonstrated that the friction of an ‘ideal’ granular assemblage—composed of smooth, rigid, spherical particles—represents a unique threshold for solid-liquid interactions, independent of grain mineralogy. This friction value serves as both a lower bound for lubrication effect that dominates the behavior of grains-assembly system and an upper limit for adhesion effect that dominates the behavior of grains-to-surface system. These findings provide a thorough insight into the fundamental understanding of granules behavior, by shedding light on the complex relationships between particle properties, liquid interactions, the grains displacement mechanism, and the resulting bulk friction.

Data availability

The properties and analysis of the materials used in this study are detailed in the Supplementary Information file. All analyzed data are presented within the manuscript. The raw experimental data can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Duran, J. & Behringer, R. Sands, Powders, and Grains: An Introduction to the Physics of Granular Materials. Vol. 54. (2001).

Tahmasebi, P. A state-of-the-art review of experimental and computational studies of granular materials: properties, advances, challenges, and future directions. Prog Mater. Sci. 138, 101157 (2023).

Jaeger, H. M., Nagel, S. R. & Behringer, R. P. Granular solids, liquids, and gases. Rev. Mod. Phys. 68, 1259–1273 (1996).

Santamarina, J. C. Soil behavior at the microscale: Particle forces. In: Soil Behavior and Soft Ground Construction, 25–56 (ASCE, 2003).

Mitchell, J. K. & Soga, K. Fundamentals of Soil Behavior. Vol. 3 (Wiley, 2005).

Aranson, I. S. & Tsimring, L. S. Patterns and collective behavior in granular media: theoretical concepts. Rev. Mod. Phys. 78, 641–692 (2006).

Terzaghi, K. Theoretical Soil Mechanics (Wiley, 1943).

Terzaghi, K., Peck, R. B. & Mesri, G. Soil Mechanics in Engineering Practice. 3 Ed. (Wiley, 1996).

Bishop, A. W. The principle of effective stress. Tek Ukebl. 106, 859–863 (1959).

Skempton, A. W. Effective stress in soils, concrete and rocks in Pore Pressure and Suction in Soils (Butterworths, London, 4–16. (1961).

Meegoda, J. N., Chen, B., Gunasekera, S. D. & Pederson, P. Compaction characteristics of contaminated soils-reuse as a road base material. Geotech Spec. Publ. 195–209 (1998).

Ratnaweera, P. & Meegoda, J. N. Shear strength and Stress-Strain behavior of contaminated soils. Geotech. Test. J. 29, 1–8 (2006).

Khamehchiyan, M., Hossein Charkhabi, A. & Tajik, M. Effects of crude oil contamination on geotechnical properties of clayey and sandy soils. Eng. Geol. 89, 220–229 (2007).

Khodary, S. M., Negm, A. M. & Tawfik, A. Geotechnical properties of the soils contaminated with oils, landfill leachate, and fertilizers. Arab. J. Geosci. 11, 13 (2018).

Cho, G. C., Dodds, J. & Santamarina, C. Particle shape effects on packing density, stiffness, and strength: natural and crushed sands. J. Geotech. Geoenvironmental Eng. 132, 591–602 (2006).

Thakur, M. M. & Penumadu, D. Influence of friction and particle morphology on triaxial shearing of granular materials. J. Geotech. Geoenvironmental Eng. 147, 1–15 (2021).

Elhassan, A. A. M., Mnzool, M., Smaoui, H., Jendoubi, A. & Elnaim, B. M. E. Faihan alotaibi, effect of clay mineral content on soil strength parameters. Alexandria Eng. J. 63, 475–485 (2023).

Andrade, J. E., Avila, C. F., Hall, S. A., Leonir, N. & Viggiani, G. Multiscale modeling and characterization of granular matter: from grain kinematics to continuum mechanics. J. Mech. Phys. Solids. 59, 237–250 (2011).

Misra, A., Placidi, L. & Turco, E. Variational methods for evolution. In Encyclopedia of Continuum Mechanics. Vol. 17. 1391–1467 (Springer, 2019).

Santamarina, J. C. & Shin, H. Friction in Granular Media (2009).

Santamarina, J. C. & Cho, G. C. Soil behaviour: The role of particle shape. In Conference on Advances in Geotechnical Engineering, London. 604–617 (2004).

Pinzón, G. A. Experimental investigation of the effects of particle shape and friction on the mechanics of granular media. Grenoble Alpes (2023).

Lakkimsetti, B. & Latha, M. Grain shape effects on the liquefaction response of Geotextile – Reinforced sands. Int. J. Geosynth Gr Eng. 9, 1–17 (2023).

Miron, A., Tadmor, R., Multanen, V. & Pinkert, S. Da vinci’s friction for granular media. Sci. Rep. 15 (2025).

Veltkamp, B., Velikov, K. P., Venner, C. H. & Bonn, D. Lubricated friction and the Hersey number. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 44301 (2021).

Miron, A., Tadmor, R. & Pinkert, S. Decoupling the mechanical role of pore liquids in soils to liquid viscous effect and solid–liquid adhesion effect. Acta Geotech. 18, 95–104 (2023).

Tadmor, R. et al. Solid – liquid work adhesion. Langmuir 33, 3594–3600 (2017).

Yadav, S., Gulec, S., Tadmor, R. & Lian, I. A novel technique enables quantifying the molecular interaction of solvents with biological tissues. Sci. Rep. 9, 1–9 (2019).

Dai, B. B., Yang, J. & Zhou, C. Y. Observed effects of interparticle friction and particle size on shear behavior of granular materials. Int. J. Geomech. 16, 04015011 (2016).

Rowe, P. W. The stress-dilatancy relation for static equilibrium of an assembly of particles in contact. In Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. Vol. 269. 500-527. http://rspa.royalsocietypublishing.org/cgi/doi/. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.1962.0193) (1962).

Skinner, A. E. A note on the influence of interparticle friction on the shearing strength of a random assembly of spherical particles. Géotechnique 19, 150–157 (1969).

Adamson, A. W. & Gast, A. P. Physical Chemistry of Surfaces. 6 Ed. (Wiley, 1997).

Israelachvili, J. N. Intermolecular Surface Forces. 3 Ed. (Academic, 2010).

Ruths, M. Surface forces, surface tension, and adhesion. In (Wang, Q. & Chung, Y. Eds. ) Encyclopedia of Tribology. 3435–3443 (Springer, 2013).

Vinod, A. et al. Measuring surface energy of solid surfaces using centrifugal adhesion balance. Phys. Rev. E. 110, 1–12 (2024).

Suiker, A. & Fleck, N. A. Frictional collapse of granular assemblies. J. Appl. Mech. – Trans. ASME. 71, 350–358 (2004).

Gong, J., Zou, J., Zhao, L., Li, L. & Nie, Z. New insights into the effect of interparticle friction on the critical state friction angle of granular materials. Comput. Geotech. 113, 103105 (2019).

Liu, J. L., Feng, X. Q., Wang, G. & Yu, S. W. Mechanisms of superhydrophobicity on hydrophilic substrates. J Phys. Condens. Matter 19 (2007).

Yildirim Erbil, H. & Elif Cansoy, C. Cansoy Range of applicability of the Wenzel and cassie-baxter equations for superhydrophobic surfaces. Langmuir 25, 14135–14145 (2009).

Acknowledgements

We thank Pazy foundation, Israel, for partial support of this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A. M. and S.P. conceptualized this study, conducted the analysis, and wrote the main manuscript text. A.M. performed the laboratory experiments. S.P. and R.T. are the PIs of this research.V.M. and A.M. prepared the Supplementary Material.All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Miron, A., Tadmor, R., Multanen, V. et al. Friction of granular systems: the role of solid–liquid interaction. Sci Rep 15, 34051 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14045-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14045-5