Abstract

To master the overburden structure failure and fracture evolution law under multi-key stratum control during repeated mining in coal seams, this study takes the superimposed mining faces of 6# and 7# coal seams in Xinjiang mining area as the research background. Through comprehensive research methods including theoretical analysis, similarity simulation, numerical simulation, and field monitoring, it systematically reveals the evolution law of overburden fractures under repeated mining controlled by multiple key strata, and clarifies the crucial control effects of cumulative damage in the overburden and the superimposed effect of mining-induced stress fields on fracture morphology during repeated mining of close-distance coal seams. The research shows: (1) Based on key stratu theory, four key strata are identified above the working face, with the first sub-key stratum and the main key stratum located at 61.63 m and 174.63 m above the 7# coal seam, respectively. (2) Similarity simulation displays that after mining the upper 6#coal seam, the overburden failure exhibited an approximately “trapezoidal” distribution, with a fracture zone height of 40.2 m (height-to-mining ratio of 13.4); the fracture zone height in the area unaffected by repeated mining above the 7# coal seam was 115 m (height-to-mining ratio of 12.8). Repeated mining intensifies cumulative damage in the overburden and superimposes mining-induced stress fields, leading to rapid fracture propagation. Ultimately, under the combined control of multiple key strata, the fracture zone and caving zone heights stabilizes at 139.68 m and 42.88 m, respectively. The overburden failure pattern evolves from the single “trapezoidal” structure of initial mining to a "double-trapezoidal" composite structure, with fracture evolution following the pattern of "slow expansion during initial disturbance-leap increase due to cumulative damage from repeated mining-gradual stabilization regulated by key strata". (3) Field monitoring using the double-end water plugging and borehole observation joint detection method measures the fracture zone height after 6# coal seam mining as 38 m (height-to-mining ratio of 13.6 based on a measured seam thickness of 2.8 m), and the fracture zone height in the exclusively mined area of the 7# coal seam as 100.33 m (height-to-mining ratio of 12.4 based on a measured seam thickness of 8.09 m). The predicted height-to-mining ratios under different coal thickness conditions show good agreement. The research results provide a theoretical basis for roof water hazard prevention and control and surface damage management in the Xinjiang mining area.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the gradual depletion of coal resources in eastern mining areas in China, the strategic focus of coal development has rapidly shifted to northwest mining areas characterized by superior geological conditions. Xinjiang and other western mining regions not only possess advantages such as vast reserves, high-quality coal, simple geological structures, shallow burial depths, and ultra-thick coal seams, but their unique high-intensity repeated mining mode has also become a defining technical feature of regional exploitation1,2. However, the cumulative damage effects on overlying strata induced by repeated mining of ultra-thick coal seams significantly increase risks, including water-conducting fractures penetrating the surface and catastrophic roof water–sand inrushes, severely restricting safe and efficient mining operations3,4,5,6. Therefore, investigating the failure mechanisms and fracture evolution patterns of overlying strata under repeated mining of ultra-thick coal seams, and accurately predicting the developmental height of water-conducting fracture zone (WCFZ) under such conditions, are critical for preventing roof water hazards and protecting surface collapses.

Extensive research has established a systematic framework for addressing these challenges. Cao7,8 and Du et al.9,10 investigated structural stability and disaster prevention in coal mine overburden by integrating mechanical modeling, numerical simulation, and industrial testing. Their research focused on the mechanical properties and fracture evolution of overburden, revealing stress arch evolution laws during grout diffusion, thick-hard roof fracturing, and remaining coal pillar extraction. Mining-induced stress arches form dynamic bearing systems controlled by key strata, in which stiffness characteristics11,12 and energy release mechanisms13 directly influence coal mass-instability and support-structure adaptability. By constructing dual-body systems, fold catastrophe theory, and stress arch models, they proposed key technologies for grouting parameter optimization, rock burst prevention, and hydraulic support selection, providing theoretical support for overburden structure regulation and safe mining under complex conditions. Xu et al.14,15 developed a WCFZ height prediction model based on key strata theory, elucidating how structural differences in primary key strata control fracture morphology evolution. Lai et al.16 clarified the formation mechanisms of water-conducting channels through studies on overlying strata fracturing in fully mechanized caving faces. Gao et al.17 innovatively combined engineering analogy and numerical simulation to determine the regulatory role of key strata in surface subsidence and quantified the heights of caved zones and fracture zones (“two zones”). Addressing limitations of conventional theories, He et al.18 proposed an improved key strata (IKS) theory, incorporating dynamic overlying strata deformation, and established a WCFZ prediction method that explains differences in mining patterns between northwestern and eastern coalfields. Majdi et al.19 introduced five mathematical models for estimating WCFZ heights in longwall mining, revealing quantitative relationships: The short-term height and long-term height are 6.5–24 times and 11.5–46.5 times of the mining height respectively. Sun20identified“stepwise”overlying strata collapse patterns and quantified shear stress influence distances (92.7 m) using distributed optical fiber monitoring. Huang21, Zang et al.22 through numerical simulations and mechanical modeling analyses of fracture and stress evolution patterns in overlying strata under mining with different bedrock thicknesses, this study reveals that increased bedrock thickness enhances the bearing capacity of key stratum structures, prolongs the interval of immediate roof caving, and induces a deep shift of coal wall stress peaks with expanded influence zones, elucidating the underlying mechanical mechanisms. Lin23, Wang et al.24,25,26 analyzed crack evolution patterns in rock masses under stress based on geometric features of rough fractures (e.g., dip angle, JRC values), revealing that fracture dip angles and JRC govern the fractal characteristics and connectivity of water-conducting fractures. High-JRC fractures tend to form locally interconnected channels under low stress, while high-dip-angle fracture clusters promote large-scale conductive network development through shear slippage. Qu27, Li28, Yang et al.29 systematically revealed WCFZ evolution in central-eastern mining areas under complex strata, establishing a multi-factor prediction model integrating mining height, lithology, and disturbance effects. To address the water inrush disaster mechanisms in karst collapse columns, Cao30,31, Jia et al.32 conducted systematic research integrating nonlinear coupled mechanical models, bifurcation theory, and variable-mass fluid–solid coupling numerical simulation methods. Triaxial seepage tests revealed the spatiotemporal evolution of porosity in fractured rock masses and the three-stage characteristics of seepage velocity:"gradual transition—abrupt transition—steady-state."A heterogeneous rock mass multi-field coupling model based on Weibull distribution theory clarified the permeability leap induced by particle migration and the formation mechanisms of multi-scale conductive channels. Numerical simulations and field monitoring validated critical seepage instability thresholds, identifying that when the Darcy flow deviation factor falls below a critical value, saddle-node bifurcation triggers abrupt seepage transitions. Key controlling param for water inrush disasters—hydraulic gradient, initial porosity, and rock mass homogeneity index—were quantitatively determined, providing a multi-scale dynamic theoretical foundation for preventing karst water inrush in deep mines. Teng et al.33,34 Presented a novel approach that incorporates nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) measurement and triaxial loading chamber to accomplish the laboratory in situ continuous observation of the pore-fracture evolution in the coal-rock samples during triaxial compression. Triaxial compression tests with in situ NMR observation were conducted on coal and sandstone samples. The evolution of pore-fractures and permeability in a complete stress–strain process was detected in situ. In multi-seam repeated mining research, Ren35 demonstrated the transformation of overlying failure patterns from“trapezoidal”to“superimposed trapezoidal”in close-distance seams, with WCFZ heights increasing from 64.5 m to 158.5 m. Kang36 developed a principal component-fuzzy comprehensive evaluation model incorporating six weighted factors (e.g., mining thickness and depth) for WCFZ prediction. Teng37 quantified a 26.2% increase in upper-seam WCFZ heights and nonlinear growth patterns of failure volumes under repeated mining. Scholars including Wang38, Yu39, Hou40 and Chen et al.41 systematically investigated the temporal-spatial evolution characteristics of WCFZs in overlying strata under multi-seam superimposed mining conditions through multi-scale coupled numerical simulations. Their work quantitatively characterized the nonlinear mechanisms governing the influence of inter-seam spacing, extraction thickness ratio, and repeated mining-induced disturbances on the developmental height of fracture zones under stratified and coordinated extraction modes. Brigida42, Hu43 and Dzhioeva et al.44 developed a 3D regression model incorporating natural indicators (e.g., methane concentration in gas-air mixtures extracted underground) to effectively quantify the nonlinear dynamic characteristics of mining pressure, providing a data-driven approach for quantitative prediction of overburden fracture and stress evolution. These theoretical advancements have significantly enriched the understanding of overburden fracture evolution mechanisms during coal mining.

The Xinjiang mining area hosts a large number of closely spaced extra-thick coal seams (9 m thick, average spacing 13.2 m), where the fracture evolution mechanism in overlying strata under repeated mining presents distinct characteristics due to superimposed multi-field coupling effects. Repeated extraction significantly increases the development height of WCFZs compared with single-seam mining, induces larger overburden subsidence, and enhances fracture network connectivity that facilitates water migration channels, leading to surface subsidence, roof water inrush, and landslides. However, existing research inadequately addresses the spatiotemporal evolution mechanisms of overburden fractures under repeated mining of such typical Xinjiang coal seams, with traditional theories and empirical formulas showing significant prediction errors. This urgently requires multi-scale analysis of fracture field evolution, multi-method precise detection, systematic revelation of fracture evolution patterns in closely spaced extra-thick seams under repeated mining, and establishment of a dynamic prediction model for fracture zone height based on geomechanical conditions. To address this, this study takes the superimposed working faces of the 6# and 7# coal seams in Xinjiang’s 106 Coal Mine as the engineering context. Within the framework of key strata theory, we integrate physical similarity simulation, 3D numerical modeling, and multi-method in-situ monitoring technologies to systematically reveal the spatiotemporal evolution laws of overlying strata fractures under high-intensity repeated mining. The research develops a staged fracture propagation model and elucidates the regulatory mechanisms of key stratum rupture on fracture development. This study establishes a theoretical foundation for prevention and control of water hazard and surface collapses in Xinjiang mining areas.

Research area overview

The 106 Coal Mine is located in Hutubi County, Xinjiang, featuring a south-high-north-low topography with high geomorphological complexity. The study area exhibits dense vegetation coverage, densely developed gullies, and significant surface dissection. The region belongs to a belted mountain structure, where the northern slope has a gradient of 15° ~ 20°, while the southern slope exposes large areas of bedrock. The southern zone primarily comprises fire-affected geomorphic units, and the western boundary is dissected by the Hutubi River flowing south-north, forming a typical north–south trending canyon terrain.

The study focuses on the superimposed working faces 1602 and 1702 within Panel 1, with an average vertical spacing of 13.2 m. The upper 1702 working face overlies the 1602 working face, adjacent to the panel rise protective coal pillar to the west (marked by the red curve in Fig. 1) and bordered by the goaf areas of Panels 1603 and 1601 to the south and north, respectively. The 1602 working face extracts 6# coal Seam, with a strike length of 1,079.5 m, dip length of 185.6 m, coal thickness ranging 1.4 ~ 3.5 m, average mining height of 3.0 m, and a seam dip angle of 15°. The 1702 working face adjoins the 1703 goaf to the south and borders a preparatory working face to the north, primarily mining the ultra-thick 7# coal Seam. It extends 1,102.5 m along the strike, 197 m along the dip, with coal thickness varying 7.1 ~ 12.9 m and an average mining height of 9.0 m. The spatial configuration of the working faces is illustrated in Fig. 1.

The stratigraphic sequence of the mining field, from bottom to top, comprises: Lower Jurassic Sangonghe Formation (J1s), Middle Jurassic Xishanyao Formation (J2x), Middle Jurassic Toutunhe Formation (J2t),Quaternary System (Q)。The Xishanyao Formation aquifer (J2x) serves as the primary water-bearing disaster unit in the mining area. Its lithology is characterized by interbedded layers of coarse sandstone, medium sandstone, and siltstone, exhibiting weak water abundance. This aquifer is recharged by atmospheric precipitation, snowmelt water, fracture water infiltration from shallow burnt rocks, and topography-driven runoff, forming an engineering-significant groundwater body. The Xishanyao Formation is subdivided into two lithologic members (J2x1 and J2x2) based on lithological features, containing four coal seams. The study focuses on 6# and 7#coal Seams, both hosted within the lower first lithologic member (J2x1).

Fracture evolution characteristics under repeated mining

To elucidate the dynamic evolution mechanisms of overburden fractures under repeated mining controlled by multi-layer key strata, a three-dimensional physical similarity simulation system was developed based on the spatial superposition theory of key strata. Utilizing a phased extraction-compaction cyclic loading protocol, this system integrates Digital Image Correlation (DIC) technology to capture fracture network distribution characteristics in real time, enabling visual characterization of the full-cycle evolution process of mining-induced fractures—from mesoscale initiation to macroscale connectivity.

Physical similarity simulation of fracture evolution

Key strata identification and experimental design

Xu et al.45 established a practical method for identifying key strata in overlying rock masses. This approach involves: (1) screening candidate key strata: Sequentially identifying hard rock layers with high strength and deformation resistance from the bottom upward; (2) calculating fracture spans: Comparing the breaking spans of potential key strata using the composite beam theory. Assuming the first layer is a hard stratum, the load imposed by overlying strata is calculated as:

In the formula: q1(x) |n represents the load imposed by then-th layer on the first hard stratum; hi is the thickness of the layer i (m); Vi is the unit weight of the layer i (kN/m3);Ei is the elastic modulus of the layer i, (MPa).

Using Eq. (1), the loads q1(x) |m and q1(x) |m+1 imposed by the m-th and (m + 1)-th layers on the first hard stratum are calculated. It necessarily follows that q1(x) |m+1 < q1(x) |m. Based on this criterion, the positions of hard strata are determined. Subsequently, the breaking spans lk of different hard strata are calculated to identify the main key strata and sub-key strata:

In the formula: hk is the thickness of the hard rock strata, (m); Tk is the tensile strength of the hard rock strata, (MPa); qk is the load applied to the hard rock strata, (MPa); mk is the number of soft rock stratas controlled by the k-th hard rock strata; Ek,j is the elastic modulus of the j-th strata in the soft rock group controlled by the k-th hard rock strata, Ek,0 is the elastic modulus of the k-th hard rock strata itself (MPa); hk,j is the thickness of the j-th soft rock strata, hk,0 is thetotal thickness of the k-th hard rock strata itself (m); Vk,j is the unit weight of the j-th soft rock layer, (kN/m3).

For overlying strata containing a surface soil layer, the load on the uppermost hard strata (n-th layer) is modified as:

In the formula: H is the thickness of the surface soil layer, (m); V is the unit weight, (kN/m3); Ek,0 is the elastic modulus of the n-th hard rock strata itself (MPa); hn,0 is thetotal thickness of the n-th hard rock strata itself (m).

By comparing the breaking spans of hard strata, the key strata positions are determined, where the hard stratum with the maximum breaking span is identified as the main key strata, while others are classified as sub-key strata.

Applying this method, the key strata identification results for Mine 106 are obtained as shown in Table 1. The layers at 61.63 m and 174.63 m above 7#coal Seam are identified as the first sub-key strata and main key strata, respectively.

Based on similarity theory and the occurrence conditions of the 6# and 7# coal seams in the 106 Coal Mine, a physical similarity model with dimensions of 275 cm × 37 cm × 180 cm (length × width × height) was constructed using sand as the aggregate, calcium carbonate-gypsum composite cementitious material, and borax retarder. The experimental setup adheres to the similarity simulation criteria46,47,48 outlined in Table 2, with the specific material ratios for the analog strata provided in Table 3.

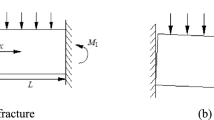

The simulation scope extended 20 cm below the floor of the 7# coal seam. The mining heights of the 6# and 7# coal seams were 1.7 cm and 4.8 cm, respectively, with an interlayer spacing of 6.6 cm. The mining lengths of both working faces were 175 cm. To eliminate boundary effects and match actual conditions, a 35 cm (equivalent to 70 m) coal pillar was reserved on the left side of the 6# coal seam, and a 65 cm (equivalent to 130 m) coal pillar on the right side. For the 7# coal seam, 65 cm and 35 cm coal pillars were reserved on the left and right sides, respectively (Fig. 2). The evolutionary morphology of overlying strata fractures during working face advancement was dynamically observed using a DIC monitoring system (Fig. 3). The model design fully accounted for the distribution of key strata and stress transfer characteristics, laying the foundation for subsequent analysis of overlying strata failure patterns.

Overburden failure and fracture evolution characteristics during mining in the upper coal seam

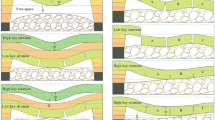

During the mining process of the 6# coal seam, the development pattern of overburden fractures is shown in Fig. 4. When the working face advanced to 45 m (Fig. 4a), the immediate roof experienced its first break and caving. The fractured rock blocks exhibited a“voussoir beam”structural feature, forming a delamination space of approximately 0.8 ~ 1.2 m above. At this stage, the height of the mining-induced fractures reached 6.9 m. As the face advanced to 130 m (Fig. 4b), the influence of mining intensified, resulting in an expanded range of overburden breakage. The fracture network continued to extend, forming a three-dimensionally connected"Z"-shaped lateral fracture at the edge of the goaf, along with a transversely connected delamination space at the top of the fracture zone. The overall geometry resembled an approximately“trapezoidal”distribution. At this stage, the height of the collapsed fragmented zone reached 6.5 m, and the total height of the water-conducting fracture zone (WCFZ) increased to 24.43 m, approximately 8.1 times the mining height. As the working face advanced further to 270 m (Fig. 4c), under the action of mining-induced stress, the overlying strata exhibited periodic breakage, and the range of the“trapezoidal”fracture network continued to expand. Numerous delamination and vertical fractures developed in the strata above the goaf, which periodically opened and closed with the progression of mining. At this stage, the height of the WCFZ rose to 40.2 m, and the caving zone developed to a height of 12.4 m. When the working face reached 310 m (Fig. 4d), vertical development of the overlying fracture network had essentially ceased, stabilizing into a“trapezoidal”form characterized by a broader base and narrower top. The height of the caving zone also stabilized, and the WCFZ height remained at 40.2 m, with a fracture-to-mining-height ratio of 13.4. In summary, during the initial extraction of the upper 6# coal seam, the vertical development rate of fractures was relatively slow. The stepwise subsidence pattern of roof rock breakage, which dominated overburden failure, was consistent with the characteristics of single-seam mining.

Overburden failure and fracture evolution characteristics under repeated mining

The characteristics of overburden failure and fracture evolution during repeated mining of the 7# coal seam exhibit a more intense and dynamic development pattern due to the combined effects of superimposed mining-induced stress fields and cumulative overburden damage, as shown in Fig. 5.

When the working face advanced to 55 m (Fig. 5a), the strata supporting the interval between the two seams fractured and collapsed, forming“voussoir beam”structures on both sides of the panel. Mining-induced fractures rapidly developed and established hydraulically connected vertical water-conducting channels with the goaf of the overlying 6# coal seam. At this point, the fracture height reached 28.7 m, with a fracture-to-mining-height ratio of 3.2. As the working face advanced to 105 m (Fig. 5b), the fractured strata in the upper goaf collapsed extensively, while interlayer rock masses underwent periodic fracturing and caving. Influenced by the cumulative damage effect from repeated mining, mining-induced fractures developed rapidly but were constrained by the bearing capacity of Sub-Key Stratum 1. A larger trapezoidal zone formed in the central region due to cumulative damage, containing numerous wide-aperture bed separation fractures and penetrating fractures. At this stage, the caving zone height reached 22.2 m, and the WCFZ height surged abruptly to 62.43 m (fracture-to-mining ratio of 6.9).

With continued advancement to 155 m (Fig. 5c), the extent of fractured overburden expanded. Under the influence of superimposed mining stress, Sub-Key Stratum 1 reached its ultimate bearing capacity and fractured, allowing fractures to develop up to the base of Sub-Key Stratum 2. Within the central trapezoidal damage zone, the rock mass was severely fractured, and the overlapped trapezoidal region increased in both height and extent, forming a through-going low-level delamination space around Sub-Key Stratum 1. At this point, the WCFZ height increased to 102.48 m, approximately 11.4 times the mining height, while the caving zone developed to 31.3 m. Upon advancing to 175 m (Fig. 5d), Sub-key stratum 2 underwent bending subsidence, generating high-level bed separations. Due to the loss of control from intermediate sub-key strata and the expansion of the overburden failure scope, the trapezoidal cumulative damage zone induced by repeated mining progressively extended. At this stage, the maximum height of the WCFZ reached 122.38 m, while the caving zone developed to 34.6 m.

During working face advancement between 255 and 350 m (Fig. 5e ~ f), the fracture development height in the overburden stabilized under the hierarchical control of multiple key strata. Throughout this phase, high-level bed separations continued propagating upward until eventual closure. Severely damaged strata within the central cumulative damage zone were gradually compacted under the subsidence of overlying fractured rock masses. Influenced by the supporting effect of boundary-staggered coal pillars, highly interconnected water-conducting channels formed around the stope. Within the repeated mining superposition-affected area (marked by the red trapezoid in Fig. 5f), the caving zone height stabilized at 42.88 m and the WCFZ height at 139.68 m (fracture-to-mining ratio of 15.5), representing a 244% increase in WCFZ height compared to single-seam mining. As the lower 7# Seam was progressively extracted toward the stopping line, overburden fractures at the working face forefront continuously propagated upward. Near the area above 7#Seam stopping line (marked by the blue trapezoid in Fig. 5f), where 6#Seam remained unmined and thus unaffected by repeated mining, the maximum WCFZ height measured 115 m, with a fracture-to-mining-height ratio of 12.8. Ultimately, a"double-trapezoid"fracture configuration formed above the goaf (Fig. 5f).

In summary, fracture development during close-distance repeated mining is regulated in a stepwise manner by multiple sub-key strata. The evolution of overburden fractures follows the pattern of “initial disturbance with slow expansion—cumulative damage surge under repeated mining—gradual stabilization under stepwise control of key strata.” Due to the stress redistribution caused by staggered pillar support and progressive failure of sub-key strata, the failure mode of the overburden transitions from the “trapezoidal” fracture zone typical of single-seam mining to a damage-accumulated “double-trapezoidal” composite structure.

Analysis of fracture and strain evolution characteristics in overburden

Analysis of images acquired by the DIC system during similarity simulation yielded strain contour maps of the overburden at different mining stages (Fig. 6), enabling further investigation into damage extent and mining-induced fracture evolution under repeated mining conditions. Using the strain state before mining (Fig. 6a) as the baseline, overburden strain patterns during extraction were analyzed. Upon completion of 6# coal seam mining (Fig. 6b), the maximum principal strain reached 0.149 within the zone spanning from above the goaf to Sub-Key Stratum 1 (corresponding to the fracture zone of 6# coal seam).

As the lower 7# coal seam progressively advanced (Fig. 6c ~ d), cumulative damage intensified in the overburden under repeated mining superposition effects. Mining-induced fractures rapidly propagated and interconnected, with notably wider apertures persistently maintained along both sides of the stope. When 7# coal seam extraction reached 175 m, the maximum principal strain within the repeated mining-affected zone increased to 0.168. Further advance to 255 m induced additional strain growth in this zone, peaking at 0.170. However, in the central superposition-affected area, overburden strain exhibited a decreasing trend due to compaction following strata fracturing and subsidence.

This analysis demonstrates that maximum principal strain at fixed overburden locations continuously increased with face advance until strata fracturing and caving occurred. Simultaneously, influenced by overlying rock caving deformation and fracture evolution, both the spatial influence range and magnitude of maximum principal strain induced by repeated mining exhibited progressive amplification.

Numerical simulation analysis of fracture evolution under repeated mining

Based on the occurrence characteristics of close-distance coal seams in the 106 Coal Mine, a numerical model was established. The plastic zone evolution in overlying strata during repeated mining was analyzed to further investigate the developmental patterns of fracture zones under repeated mining of close-distance ultra-thick coal seams.

Based on the geological conditions of the working faces in 6# coal seam and the 7# ultra-thick coal seam at Coal Mine 106, along with the physical–mechanical parameters of the coal seam roof and floor strata obtained through laboratory testing (Table 4), a numerical model measuring 800 m long × 600 m wide × 300 m high was established using the Mohr–Coulomb failure criterion. To eliminate boundary effects, 200 m-wide boundary coal pillars were set along both the strike and dip directions of the model, with fixed displacement boundaries applied to all lateral sides and the bottom boundary.

Numerical simulation findings for isolated mining of the upper coal seam

The coupled evolution characteristics of overburden damage and stress fields during the isolated mining of the 6# coal seam are obtained. When the working face advanced to 50 m, the overlying strata above the seam predominantly experienced shear failure, with a limited influence range from mining-induced stress, and the height of fracture development reached 12 m. As the working face progressed to 200 m, large-scale fracturing and collapse occurred in the overburden, and the mining-induced fractures continuously propagated upward, reaching a height of 31 m. When the working face advanced to the range of 350–400 m, the panel entered the fully mined-out stage. At this stage, the WCFZ exhibited dynamic horizontal propagation and closure, while vertical development tended toward stabilization, eventually stabilizing at a height of 48 m.

Simultaneous monitoring of the stress field indicated that the peak abutment pressure increased from an initial value of 9.46 MPa to 11.32 MPa. With the continuous advancement of the working face, the stress in the pressure-relieved area above the goaf gradually recovered, and the overburden underwent a recompaction process. Eventually, the stress field in the overburden above the goaf tended toward a stable state.

Numerical simulation results under repeated mining conditions

The coupled evolution characteristics of cumulative overburden damage and mining-induced stress fields under repeated mining are obtained. Under the influence of repeated mining in the dual coal seams, the overburden fracture network underwent dynamic reconstruction. When the working face advanced to 50 m, due to the superimposed effects of the overlying mining-induced stress, interlayer strata experienced failure, and the fracture network rapidly developed and gradually became hydraulically connected. Upon advancing to 200 m, driven by cumulative damage effects, the overburden fractures evolved intensively: The rock mass within the central cumulative damage zone underwent large-scale fracturing and collapse, with the fracture network rapidly penetrating through the overburden and forming a saddle-shaped fracture distribution—lower in the center and slightly higher on both sides.

As the working face continued to advance, lateral fractures with large apertures and high connectivity progressively developed at both ends of the panel. Under the stepwise control of multiple key strata, the height of the WCFZ eventually stabilized at 134 m, representing a 179% increase compared to single-seam mining. Simultaneously, the central rock mass underwent compaction following collapse. Ultimately, a “saddle-shaped” WCFZ characterized by higher ends and a lower center was formed.

Simultaneous monitoring results showed that a mining-induced stress concentration as high as 13.24 MPa developed in the coal pillar zone at the lateral boundary of the goaf of the 7# coal seam. With the continuous retreat of the working face, the original overburden stress field was significantly disrupted, and the impact of mining disturbance on the surrounding rock stress became more severe. The stress in the pressure-relieved zone at the center of the goaf gradually recovered, while the peak abutment pressure increased further and migrated deeper into the coal wall as mining progressed. Ultimately, a new dynamic stress equilibrium was established over a larger area.

Evolution law of the WCFZ induced by repeated mining

Based on numerical simulation results, the evolution pattern of the WCFZ under repeated mining can be summarized as follows: During the initial disturbance, overburden failure led to a slow vertical extension of fractures. Upon entering the repeated mining stage, driven by cumulative damage effects, fracture development experienced a sharp escalation, with the WCFZ height increasing dramatically by 179% compared to single-seam mining, forming a highly connected fracture network and a saddle-shaped spatial configuration. Eventually, under the stepwise control of multiple key strata, both the height and morphology of the WCFZ tended toward dynamic stability, with a final stabilized height of 134 m. Simultaneously, the overburden stress field underwent significant adjustments and reestablished a new dynamic equilibrium, as shown in Fig. 7.

Multi-method field monitoring validation

To verify the reliability of the theoretical model for overburden fracture evolution under repeated mining, a combined observation approach integrating the double-end borehole water injection sealing method and borehole camera technology was employed to conduct comprehensive detection of the “two-zone” heights above the repeated mining working face in the close-distance, extra-thick coal seams of the Xinjiang 106 Mine. A feedback validation system was established through the integration of numerical simulation, physical modeling, and field measurements.

Borehole observation design

Guided by the theoretical calculation formulas for"Two-Zone"heights (caving zone and WCFZ) specified in relevant codes49,50, a multi-method collaborative detection scheme was implemented at the 1702 working face of the 106 Mine. Due to severe overburden damage in repeated mining areas hindering borehole layout, drill sites were positioned near the stopping lines of 6#coal seam and 7# coal seam to exclusively detect overburden failure characteristics after single-seam extraction. Specifically, a post-mining detection drill site for 6#coal seam was arranged in the 1702 haulage roadway while a detection drill site for the 7#coal seam was established near the stopping line in the 1702 materials roadway, with each drill site following a"3 + 1"configuration comprising three observation boreholes and one reference borehole (technical parameters detailed in Table 5; borehole layout shown in Fig. 8).

Field observation results analysis

In the detection of the overburden failure zone, a comprehensive monitoring system combining the double-end water injection leakage method and borehole imaging technology was employed. The double-end water injection leakage method uses a hydraulically driven double-packer to isolate specific test sections within the borehole (Fig. 9a), and monitors water injection volume changes using a high-precision flow meter. When the test section lies within the WCFZ, the influence of mining-induced secondary fracture networks can cause the permeability coefficient of the fractures to increase by 2–3 orders of magnitude, resulting in an exponential increase in water loss. The borehole imaging method uses the YCJ90/360(A) borehole camera system (Fig. 9b), which integrates a high-resolution imaging system mounted at the front of the push-type drill rod to dynamically observe the distribution and morphology of fractures within the borehole.

Analysis of fracture distribution characteristics in overburden above 6# coal seam

The field water loss monitoring results for the 6# coal seam are shown in Fig. 10a. Monitoring data indicate that the control borehole located in the coal pillar zone exhibited relatively stable water loss rates ranging from 0.2 to 3.4 L/min, reflecting typical characteristics of primary fracture seepage. In observation borehole 1, water loss sharply increased to 12.6–18.4 L/min within the vertical depth range of 14.01 ~ 33.24 m, representing more than a 15-fold increase and indicating a significant seepage anomaly. Observation borehole 2 showed a continuous rise in water loss within the 17.69 ~ 38.00 m section, with a peak value of 21.3 L/min, suggesting that fractures in this interval are well-developed and highly connected. Observation borehole 3 exhibited a stepped increase in water loss between 10.23 and 34.94 m. All three observation boreholes recorded significant surges in water loss within their respective test intervals, confirming that these sections fall within the WCFZ. Subsequently, the water loss rapidly declined to low levels, indicating that the boreholes had penetrated beyond the upper boundary of the WCFZ and entered undisturbed, intact overburden strata.

Comprehensive determination revealed that the maximum development height of the WCFZ above 6# coal seam reached 38.00 m. Given the field-measured coal thickness of 2.8 m, the fracture-to-mining ratio was calculated as 13.6. These field measurements showed close agreement with both the empirical formula result (40.36 m) and the similarity simulation outcome (40.2 m), thereby verifying the reliability of the simulation results.

Analysis of fracture distribution characteristics in overburden above 7# coal seam

Borehole camera observations (Fig. 11 and Fig. 12) further revealed the distribution characteristics of the overlying strata. The borehole wall of the 7# coal seam control hole remained intact (Fig. 11a), showing only a few closed joints, indicating that it was located in an area not significantly affected by mining. In Borehole 1, a distinct interface was observed at a depth of 100.33 m (Fig. 11b); above this interface, severe borehole wall damage and a well-developed network of fractures were present. This depth corresponds to the water loss peak (25.6 L/min) shown in Fig. 10b, thus identifying 100.33 m as the upper boundary of the WCFZ in Borehole 1.

Similarly, Borehole 2 exhibited significantly increased water loss between depths of 32.5 m and 95.2 m, with borehole observations indicating well-developed vertical fractures in this interval (Fig. 12c); above 99.44 m, water loss returned to baseline levels and the borehole wall remained intact. Therefore, the upper boundary of the WCFZ at Borehole 2 was determined to be at 99.44 m. Borehole 3, used for detecting the collapse zone of the 7# coal seam, showed cavity and separation phenomena at a depth of 43.7 m, with the underlying rock mass exhibiting blocky fracturing characteristics (Fig. 12d), consistent with typical collapse zone damage. Combined with the water loss data in Fig. 10b, the collapse zone height at this borehole location was confirmed as 43.7 m.

Accordingly, analysis confirmed that the maximum development height of the WCFZ above 7#coal seam reached 100.33 m. With a coal thickness of 8.09 m measured in the detection area, the fracture-to-mining ratio was determined as 12.4, while the caving zone height measured 43.7 m, yielding a caving-to-mining ratio of 5.4.

Overburden failure morphology and fracture evolution law under repeated mining

Physical similarity simulation revealed that during the initial mining of the upper 6# coal seam, the overlying strata experienced periodic fracturing, with the vertical development rate of the WCFZ being relatively slow compared to the repeated mining stage. Upon entering the full mining stage, a trapezoidal fracture damage zone—wider at the bottom and narrower at the top—was formed above the goaf. The repeated mining of the lower 7# extra-thick coal seam intensified the cumulative damage effect on the overlying strata, causing rapid development of mining-induced fractures that connected with the goaf of the upper 6# coal seam. Under the hierarchical regulation of multiple key strata, the fracture development of the overlying strata gradually stabilized, eventually forming a “double trapezoidal” composite fracture structure. Influenced by the staggered coal pillar support at the mining boundary, strong, well-connected water-conducting fractures formed near the boundary of the central cumulative damage “trapezoidal zone,” becoming a long-term dominant water inrush channel for the working face, while the central area gradually compacted due to overlying strata fracturing and subsidence. Numerical simulation further confirmed the reconstruction of the mining-induced stress field and the significant overlying strata damage caused by repeated mining of the extra-thick coal seam.

Comparative analysis through multiple methods (Table 6) revealed that within the cumulative damage-affected zone under repeated mining, the WCFZ heights predicted by physical similarity simulation (fracture zone height: 139.68 m, fracture-to-mining ratio: 15.5) and numerical simulation (fracture zone height: 134 m, fracture-to-mining ratio: 14.9) showed close agreement, with a minor discrepancy of only 5.68 m. This slight deviation primarily originated from the idealized model and boundary constraints adopted in numerical simulation, which failed to fully capture the complex nonlinear failure behavior of similar materials (e.g., anisotropy in dynamic fracture propagation), leading to localized deviations in predicted fracture orientation and height. However, the 6#coal seam and 7#coal seam thickness measured at the field monitoring location was 2.8 m and 8.09 m, differing from the 3 m (6#coal seam) and 9 m (7#coal seam) thickness used in both similarity and numerical simulations. Consequently, direct comparison of absolute WCFZ heights was deemed inappropriate, making the fracture-to-mining ratio within the same panel a more suitable comparative metric. Similarity simulation results (Table 6) indicated fracture-to-mining ratios of 13.4 for isolated mining of 6# coal seam and 12.8 for 7# coal seam in areas unaffected by repeated mining. Field measurements yielded corresponding ratios of 13.6 and 12.4, respectively. The errors between simulated and measured fracture-to-mining ratios fell within an acceptable range, confirming the reliability of simulation results. In contrast, the caving zone exhibited immediate response characteristics, with rock mass collapse synchronizing perfectly with mining advancement. Thus, the measured caving zone height (43.7 m) aligned well with the simulated prediction (42.88 m), demonstrating the dynamic evolution principle of"immediate collapse upon mining"in the caving zone.

In summary, analysis demonstrates that under the condition of single-seam mining of the upper coal seam, the overlying strata experienced relatively low damage, with the fracture expansion rate during the initial disturbance stage being slow, ultimately forming a laterally developed, low-profile “trapezoidal” distribution pattern (Fig. 13). Subsequently, under the repeated mining of the lower thick coal seam, the cumulative damage effect on the overlying strata combined with the superimposed mining-induced stress field intensified, leading to aggravated overlying strata damage and rapid development of mining-induced fractures. This promoted the fracture network evolution from the initial single “trapezoidal” structure of the first mining to a “double trapezoidal” composite structure (Fig. 14). This evolution process eventually stabilized under the stepwise fracturing regulation of multiple key strata. Within the central cumulative damage “trapezoidal” zone, the rock mass was fragmented and disorderly distributed, gradually compacting with strata fracturing and subsidence; meanwhile, lateral fractures at the boundaries of the cumulative damage zone remain highly interconnected and persistently open, thus establishing long-term preferential pathways for water influx into the working face. Through multi-method integrated research, the study systematically revealed the three-stage dynamic evolution law of overlying strata fractures under repeated mining: “initial disturbance slow expansion – repeated mining damage accumulation surge – hierarchical regulation by key strata leading to stabilization.” The maximum heights of the WCFZ and collapse zone were determined as 139.68 m (with a mining-to-seam thickness ratio of 15.5) and 40.75 m, respectively, clarifying the critical controlling role of cumulative damage and stress field superposition from close-distance repeated mining of coal seam groups on fracture morphology.

Conclusions

-

(1)

Based on key stratum theory, comprehensive analysis identified four key strata developed above the working face, with the first sub-key stratum and the main key stratum located at 61.63 m and 174.63 m above the 7# coal seam, respectively. The synergistic effect of these multiple key strata significantly regulated overburden fracture development. During initial mining (6# coal seam), the fracture zone height stabilized at 40.2 m. Under repeated mining (7# coal seam extraction), the overburden fracture development height increased markedly, with the water-conducting fracture zone rising to 139.68 m (height-to-mining ratio of 15.5), representing a 244% increase compared to single-seam mining.

-

(2)

Driven by cumulative damage in the overburden and the superimposed effect of mining-induced stress fields, the overburden failure morphology evolved from a single“trapezoidal”shape during initial mining to a"double-trapezoidal"composite structure. Within the mid-section“trapezoidal zone”of cumulative damage, the rock mass became fragmented and disordered, gradually compacting with subsidence. In contrast, lateral fractures at the boundaries of this zone exhibited high connectivity and remained persistently open, becoming dominant pathways for water inflow into the working face. During repeated mining, overburden fracture evolution followed a three-stage dynamic pattern:"slow expansion under initial disturbance – leap increase due to cumulative damage from repeated mining – gradual stabilization regulated by key strata", a process further validated by numerical simulations.

-

(3)

Given the differences between field-measured coal thicknesses (2.8 m for 6# coal, 8.09 m for 7# coal) and the thicknesses used in physical similarity simulations and numerical modeling (3 m and 9 m), direct comparison of absolute water-conducting fracture zone heights was unsuitable; therefore, the height-to-mining ratio served as a more appropriate validation metric. Comparative results indicated that the height-to-mining ratios obtained from similarity simulation (13.4 for isolated 6# coal mining and 12.8 for the area above 7# coal unaffected by repeated mining) fell within a reasonable error range compared to field measurements (12.7 for isolated 6# coal mining and 12.4 for isolated 7# coal mining). Furthermore, caving zone development exhibited the characteristic"instantaneous caving following extraction"response, with the measured height (42.88 m) showing good agreement with the simulated prediction (43.7 m), verifying the reliability of the simulation results. This research can provide a theoretical basis for controlling roof water hazards and managing surface subsidence damage in Xinjiang mining areas.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

References

Zhang, C. et al. Characteristic of the water-conducting fracture zone development in thick overburden working face with extra-large mining height in western mining area. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 7(3), 333–343 (2022).

Xie, D. L. et al. Numerical simulation study on development law of mining induced overburden separation layer in deep and thick coal seam in western mining area. Saf. Coal Mine. 55(4), 204–212 (2024).

Bian, Z. F. & Lei, S. G. Green exploitation of coal resources and its environmental effects and protecting strategy in Xinjiang. Coal Sci. Technol. 48(04), 43–51 (2020).

Wang, L. L., Chen, J. Z. & Zhang, W. G. Study on the current situation and control countermeasures of mining roof disasters in Xinjiang. Xinjiang Geol. 40(04), 561–565 (2022).

Liu, Z. G. et al. Analysis on development height of water flowing fracture zone in fully mechanized caving mining of extra thick coal seam. Coal Technol. 39(09), 119–122 (2020).

Guo, B. Study on the development law of water conduction fracture zone in close distance coal seams mining under goaf. Coal Chem. Ind. 47(03), 74 (2024).

Zhengzheng, C. et al. Diffusion evolution rules of grouting slurry in mining-induced cracks in overlying strata. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 58, 6493–6512. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-025-04445-4 (2025).

Cao, Z. et al. Disaster-causing mechanism of spalling rock burst based on folding catastrophe model in coal mine. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-025-04497-6 (2025).

Feng, D. et al. Research on overburden structural characteristics and support adaptability in cooperative mining of sectional coal pillar and bottom coal seam. Sci. Rep. 14, 11458. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-62375-7 (2024).

Feng, D. et al. Breaking law of overburden rock and key mining technology for narrow coal pillar working face in isolated island. Sci. Rep. 14, 13045. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-63814-1 (2024).

Wang, M., Wan, W. & Zhao, Y. L. Experimental study on crack propagation and coalescence of rock-like materials with two pre-existing fissures under biaxial compression. Bull. Eng. Geol. Env. 79(6), 3121–3144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-020-01759-1 (2020).

Wang, M., Zhenxing, Lu., Zhao, Y. & Wan, W. Experimental and numerical study on peak strength, coalescence and failure of rock-like materials with two folded preexisting fissures. Theoret. Appl. Fract. Mech. 125, 103830. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tafmec.2023.103830 (2023).

Wang, M., Zhenxing, Lu., Zhao, Y. & Wan, W. Peak strength, coalescence and failure processes of rock-like materials containing preexisting joints and circular holes under uniaxial compression: Experimental and numerical study. Theoret. Appl. Fract. Mech. 125, 103898. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tafmec.2023.103898 (2023).

Xu, J. L. et al. New method to predict the height of fractured water-conducting zone by location of key strata. J. China Coal Soc. 37(05), 762–769 (2012).

Wang, X. Z. et al. Influence of primary key stratum structure stability on evolution of water flowing fracture. J. China Coal Soc. 37(04), 606–612 (2012).

Lei, X. P. et al. Analysis on characteristics of overlying rock caving and fissure conductive water in top-coal caving working face at three soft coal seam. J. China Coal Soc. 42(01), 148–154 (2017).

Gao, C. et al. Study on influence of key strata on surface subsidence law of fully mechanized caving mining in extra-thick coal seam. Coal Sci. Technol. 47(9), 229–234 (2019).

He, J. H. et al. A method for predicting the water-flowing fractured zone height based on an improved key stratum theory. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 33(1), 2095–2686. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmst.2022.09.021 (2023).

Majdi, A., Hassani, F. P. & Nasiri, M. Y. Prediction of the height of destressed zone above the mined panel roof in longwall coal mining. Int. J. Coal Geol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2012.04.005 (2012).

Sun, B. Y. et al. Research on the overburden deformation and migration law in deep and extra-thick coal seam mining. J. Appl. Geophys. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jappgeo.2021.104337 (2021).

Cunhan, H. et al. Development rule of ground fissure and mine ground pressure in shallow burial and thin bedrock mining area. Sci. Rep. 15, 10065. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77324-7 (2025).

Zang, C. et al. Study on overlying strata movement and stress distribution of coal mining face with unequal thickness bedrock. Processes 13, 752. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13030752 (2025).

Lin, H. et al. Study on the degradation mechanism of mechanical properties of red sandstone under static and dynamic loading after different high temperatures. Sci. Rep. 15, 11611. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93969-4 (2025).

Wang, M. & Wan, W. A new empirical formula for evaluating uniaxial compressive strength using the Schmidt hammer test. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 123, 104094. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2019.104094 (2019).

Wang, M., Wan, W. & Zhao, Y. Prediction of the uniaxial compressive strength of rocks from simple index tests using random forest predictive model. C.R. Mec. 348(1), 3–32. https://doi.org/10.5802/crmeca.3 (2020).

Wang, M., Zhenxing, Lu., Zhao, Y. & Wan, W. Numerical study on the strength and fracture of rock materials with multiple rough preexisting fissures under uniaxial compression using particle flow code. Comput. Part. Mech. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40571-024-00811-1 (2024).

Qu, S. B. Evolution analysis of thick and hard overburden strata and water-conducting fracture zone in double key layer fully mechanized caving face. J. XI. AN. Univ. Sci. Technol. 44(05), 880–891 (2024).

Li, R. R. et al. Numerical simulation of fractured water-conduction zone by considering native fractures in overlying rocks. Coal Geol. Explor. 48(6), 179 (2021).

Yang, Y. L. & Xu, Z. H. Evolution law of water-conducting fault zone in large mining height working face under sandstone aquifer of Luohe Formation. Saf. Coal Min. 52(3), 30–35 (2021).

Cao, Z. et al. Water inrush mechanism and variable mass seepage of karst collapse columns based on a nonlinear coupling mechanical model. Min. Water Environ. 44, 259–274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10230-025-01041-4 (2025).

Cao, Z. et al. State-of-the-art review on seepage instability and water inrush mechanisms in karst collapse columns. Fluid. Dyn. Mater. Proc. https://doi.org/10.32604/fdmp.2025.062738 (2025).

Yunlong, J. et al. Nonlinear evolution characteristics and seepage mechanical model of fluids in broken rock mass based on the bifurcation theory. Sci. Rep. 14, 10982. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-61968-6 (2024).

Teng, T. et al. Water injection softening modeling of hard roof and application in Buertai coal mine. Environ. Earth Sci. 84, 54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-024-12068-1 (2025).

Teng, T. et al. In situ nuclear magnetic resonance observation of pore fractures and permeability evolution in rock and coal under triaxial compression. J. Energy Eng. 151(4), 04025036. https://doi.org/10.1061/JLEED9.EYENG-6054 (2025).

Ren, Y. W. et al. Evolution characteristics of mining-induced fractures in overburden strata under close-multi coal seams mining based on optical fiber monitoring. Eng. Geol. 343, 107802. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2024.107802 (2024).

Kang, Z., Yang, D. & Shen, P. Prediction correction modeling of water-conducting fracture zones height due to repeated mining in close distance coal seams. Sci. Rep. 14, 31611. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75346-9 (2024).

Teng, T. et al. Overburden failure and fracture propagation behavior under repeated mining. Min. Metall. Explor. 42, 219–234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42461-025-01172-w (2025).

Wang Y. Research on the dynamic law of overlying strata failure in shallow burying and short distance double coal seam mining. China university of mining and technology (2022).

Yu, X. Y., Mu, C. & Li, J. F. Development law of water-conducting fracture zone in overlying rock with layered mining under strong water-bearing body in Barapukuria coal mine. J. China Coal Soc. 47(S1), 29–38 (2022).

Hou, E. K. et al. Study on development law of water-conducting fault zone in deep gently inclined double coal seam mining. Saf. Coal Min. 53(03), 50–57 (2022).

Chen, H. F. et al. Development Law of water conducted fissure in overburden rock during the collaborative slicing of thickness-limiting and filling in extra-thick coal seams. Coal Eng. 56(05), 129–137 (2024).

Brigida, V. S., Golik, V. I. & Dzeranov, B. V. Modeling of coalmine methane flows to estimate the spacing of primary roof breaks. Mining 2, 809–821. https://doi.org/10.3390/mining2040045 (2022).

Hu, T. et al. Development law of waterconducting fracture zones in overburden above fully mechanized top-coal caving face: A comprehensive study. Processes 12, 2076. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr12102076(2024) (2024).

Dzhioeva, A. K. & Brigida, V. S. Spatial non-linearity of methane release dynamics in underground boreholes for sustainable mining. J. Min. Inst. https://doi.org/10.31897/PMI.2020.5.3 (2020).

Xu, J. L. & Qian, M. G. Method to distinguish key strata in overburden. J. China Univ. Min. Technol. 05, 21–25 (2000).

Wang, L., Zhang, W., Cao, Z., Xue, Y. & Xiong, F. Coupled effects of the anisotropic permeability and adsorption-induced deformation on the hydrogen and carbon reservoir extraction dynamics. Phys. Fluid. 37(6), 066608. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0270765 (2025).

Cao, Z. Z. et al. Experimental study on the fracture surface morphological characteristics and permeability characteristics of sandstones with different particle sizes. Energy Sci. Eng. 12, 2798–2809. https://doi.org/10.1002/ese3.1768 (2024).

Xinlei, L. et al. Study on coal drawing parameters of deeply buried hard coal seams based on PFC. Sci. Rep. 15, 21934. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08154-4 (2025).

Ping, Xu. et al. Effect of polymeric aluminum chloride waste residue and citric acid on the properties of magnesium oxychloride cement. J. Build. Eng. 101, 111864. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2025.111864 (2025).

Li, G. D. et al. A new determination method of hydraulic support resistance in deep coal pillar working face. Sci. Rep. 15, 19158. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04268-x (2025).

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (U24B2041, 52174073, 52274079); the Natural Science Foundation of Henan Province (242300421246); the Key Research and Development Program of Henan Province (251111320400); Program for the Scientific and Technological Innovation Team in Universities of Henan Province (23IRTSTHN005); Program for Science & Technology Innovation Talents in Universities of Henan Province (24HASTIT021); the cultivation project of"Double first-class"creation of safety discipline (AQ20240724); the Young Teacher Foundation of Henan Polytechnic University(2023XQG-01).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sun Chaoshang: Data curation, Methodology, Writing-original draft. Shi Chaoyang: Data curation, Writing-original draft. Zhu Zhiming: Data curation, Writing-original draft. Lin Haixiao: Conceptualization, Writing-original draft. Li Zhenhua: Conceptualization, Project administration, Resources. Du Feng: Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision. Cao Zhengzheng: Project administration, Resources. Lu Pengtao: Project administration, Resources. Liu Lin: Project administration, Resources. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent to publish

All authors of this article consent to publish.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chaoshang, S., Chaoyang, S., Zhiming, Z. et al. Overburden failure characteristics and fracture evolution rule under repeated mining with multiple key strata control. Sci Rep 15, 28029 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14068-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14068-y

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Acid mine drainage control in mining areas: identification of groundwater recharge pathways and source reduction strategies

Scientific Reports (2026)

-

Science competition-driven teaching optimization for mining engineering

Scientific Reports (2026)

-

Determination method of rational position for working face entries in coordinated mining of section coal pillars and lower sub-layer

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Effects of diagenetic stage and burial depth on the microstructure and mechanical properties of coal-bearing sandstones

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Water-induced damage mechanism and dual-radius grouting control of weakly cemented argillaceous roadways in Western China

Scientific Reports (2025)