Abstract

Growing integration of renewable energy sources (RESs) into power grids has several advantages, including reduced greenhouse gas emissions and improved energy sustainability. Despite the related benefits, RES integration also poses actual challenges, such as power quality, voltage fluctuation, and reliability concerns. This study conducts a comprehensive performance evaluation of a grid-integrated microgrid consisting of an electric vehicle (EV) charging station, wherein the Volkswagen ID4 Crozz has been adopted as the standard EV model. The microgrid will consist of solar panels, a wind energy conversion system (WECS), and a battery energy storage system (BESS), which will be used for the supply of electricity economically with a reliable power supply. ETAP simulates various operating conditions to analyze their impact on voltage stability and power quality. This study investigates the impact of EV integration on power quality and applies advanced load management strategies, such as partial loading, selective disconnection, and coordinated renewable integration. A scenario-based optimization approach is used to minimize harmonic distortion and improve voltage stability. Among the configurations that were being compared, the 60% load configuration was superior, where the 5th harmonic distortion was 0.42% and the 11th was 0.55%, performing superior to full-load and other disconnection configurations of chargers. The configuration also had superior and stable voltage levels, which bear witness to its effectiveness in enhancing power quality as well as grid stability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Motivations and background

Power quality degradation is among the severe challenges that are a result of the intermittent nature of RESs1,2,3,4,5. Solar and wind power generation experiences fluctuations based on weather, time of day, and seasonality6,7,8,9,10,11. This fluctuation can lead to power quality degradation in the form of the introduction of voltage sags, swells, and harmonics, which can compromise the reliability of the grid and even impact sensitive equipment12. The shift to renewable energy sources (RESs) and the incorporation of various technologies in microgrids bring advantages as well as challenges to the overall performance of the electrical grid13,14,15. The shift of power generation to RESs currently needs to be examined closely for its impact on the overall performance of the grid16,17,18,19. Rapid changes in voltage levels can bring challenges to the stability of the grid. Voltage instability must be tackled by advanced voltage regulation technologies and a keen focus on grid management strategies20,21,22,23.

The integration of EVs with the electric grid is a complex interaction of opportunities and challenges24,25,26. Effectively managing this dynamic variable will need a collective effort in the form of grid modernization, smart charging infrastructure, and policy institutions supporting sustainable and grid-friendly utilization of EVs. With continued technological development, the interface between EVs and the electric grid has the potential to make the energy system stronger, more efficient, and more sustainable27,28. As the number of EVs on the roads rises, their impact on the electrical grid becomes more significant. Extensive use of electric vehicles leads to a rise in the demand for electricity, especially at peak charging times29,30,31. This higher demand can strain local distribution networks and peak load management, necessitating grid infrastructure reinforcement to handle the increased power requirements. Concentration of charging in specific locations, e.g., public charging stations or residential estates, can cause grid congestion. The congestion can result in voltage reduction and undermine the overall stability of the grid, particularly in areas of high EV density.

The establishment of an extensive and dense charging infrastructure is central to enabling EV adoption. Constraints include calls for higher charging station density, standardization of charging standards, and the introduction of smart charging systems to control grid interactions32,33,34. The dynamic and generally random character of EV charging loads requires careful grid planning and management. Utilities have to anticipate and keep pace with the changes in demand such that the grid can handle the extra load without compromising reliability. EVs present the potential for demand response programs and smart charging capabilities. With the application of communications technologies, grid operators can influence EV owners to shift their charging towards off-peak hours or during the period of peak renewable generation, thus balancing load and optimizing grid efficiency35. Scheduled charging when there is high generation from RESs aligns EV consumption with cleaner generation, resulting in the reduction of carbon emissions36,37,38.

Related works

The EV charging into the grid is a dynamic and complex process with system-wide impacts for the majority of the energy system. The charging behavior of EVs can inject variability into the electricity load curve. Uncertain demand peaks, especially during peak charging times, can potentially stress the grid and necessitate generation and distribution changes39. In40, a model for an integrated system that combines EV charging and battery storage to operate alongside unpredictable WTs and PV has been developed. The objective was to facilitate the design of an advanced electrical control system capable of generating an appropriate duty cycle for stabilizing and regulating voltage at the DC/DC converter. Extensive simulations were conducted in order to assess in detail the energy management operation and performance of the proposed control system. The system successfully regulated the distribution of electric power, employing energy from the BESSs during peak load hours and charging them during off-peak hours, thereby streamlining energy consumption and enhancing the stability of the grid. This approach reduced the load on the converter and resulted in shorter charging times for EVs.

In41, an optimization algorithm designed to identify the most effective set of control parameters for a voltage source inverter has been presented. This inverter integrated PV with an EV charging station to a common grid-connected AC bus. The controller parameters were tuned using the Salp Swarm Algorithm to reduce the oscillations in the DC-bus voltage. This was achieved by balancing the active power transfer and controlling the injected harmonics onto the grid. The study simulated a theoretical level 2 AC charging station for electric vehicles under various operating conditions. The controller was evaluated by simulated test cases and real irradiance profiles.

Utilities and grid operators need to plan for load profile changes, considering the geolocation of charging stations and peak hours of charging. The addition of EVs is usually followed by the adoption of time-of-use (TOU) pricing schemes. This encourages owners of EVs to charge their vehicles during off-peak periods, thus load balancing on the grid42,43,44,45. In46, an experiment was performed on different aspects of EV charging under a TOU tariff. The study was on off-peak rates beginning at different times, from 8 P.M. to 3 A.M., and employed a real residential distribution feeder for modeling. The goal was to find the most logical time to initiate off-peak rates, both to constrain the impact of EV charging on secondary service voltage and to ensure that EVs would be charged by 7 A.M. This approach was designed to achieve optimal benefits for the grid and customers. Analysis revealed that the optimum time to initiate off-peak rates was from 11 P.M. to 12 A.M. Moreover, analysis showed that expanding TOU off-peak hours to the latter half of the peak electricity usage period is beneficial.

In47, an approach to TOU price-based scheduling for Vehicle-to-Grid (V2G), implemented by an Electric Vehicle Aggregator (EVA), has been introduced. The central goal was to optimize the synchronized charging of EVs and achieve economic benefits for several stakeholders, including EV owners and the system operator. The strategy involved the application of a price-based (PB) DR program to improve the value proposition for EV owners. The V2G scheduling problem optimization for EVA considered real-world factors such as SOC, TOU-PB DR programs, and rate modulation of charging and discharging. Simulation results indicated the effectiveness of this proposed model to efficiently handle peak loads as well as generate monetary gains for all the stakeholders involved. Furthermore, the model played a role in offering regulation services to the system operator, thereby supporting grid stability and averting unforeseen contingencies.

In48, a sophisticated charging navigation model has been introduced to optimize benefits for various stakeholders. This optimization was achieved through the implementation of a TOU pricing strategy specifically tailored for fast charging stations (FCSs). The intention was to have EVs charge during off-peak periods and thus save both EV owners and FCs operators funds. The model used was that of a Stackelberg game, with the FCS operator as the leader and EVs as the followers. By analyzing the impact of prices on charging decisions, the study proposed an EV strategy consisting of selecting the optimal charging time, charging energy, charging point, and routes in order to minimize overall EV expenses. In49, a TOU pricing structure has been implemented in the electricity market, specifically for the purpose of capturing the time-varying interactions among power plants, generation activities, ESSs, EV charging, and electricity prices.

Research gap and contributions

Despite growing research in EV integration, some essential gaps remain in the existing literature. The majority of existing studies have so far been primarily interested in economic benefits and load management strategies of EVs in the grid, e.g., using EVs as a source of backup power or for demand response50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58. This economically oriented approach has a tendency to overlook significant issues of power quality, i.e., how EV charging affects electrical harmonic distortion and voltage stability. EV charging stations employ power electronic converters to extract power, hence becoming non-linear loads that inject current harmonics into the grid. However, there are few works that account for these harmonics in detail and their influence on the grid performance. EV charging causes harmonic distortions and voltage fluctuations that are not well elaborated in most of the works, though excessive distortion can foster inefficient energy transfer, equipment overheating, and voltage instability. Recent studies have pointed out the lack of extensive research on the effect of EV grid integration on power quality, highlighting this wonderful area of research deficiency.

Another deficiency in the literature is the limited analysis of EV integration in conjunction with renewable energy sources such as solar photovoltaics and wind. The variability and intermittency of renewable energy sources can cause voltage swings and power quality degradation, including voltage sags, swells, and harmonic injection from inverters. However, the combined effect of EV charging and renewable variations remains under-examined. The majority of studies treat EV integration and renewable penetration separately or make simplified interaction assumptions between the two. Realistically, an EV charger-enabled grid-connected microgrid with renewables can have compounded effects. Solar farm output variability combined with simultaneous EV fast charging, for instance, could exacerbate voltage stability or harmonics further. Recent studies usually work with static conditions or idealized models, and little is known about such dynamic interactions. Real-time adaptive solutions to handle the fluctuating load of EVs along with the output of renewable energy sources are seldom taken into account. This leaves a void in knowledge on how to maintain power quality at realistic, fluctuating operating levels. In summary, this study demands more comprehensive studies of power quality measurement in EV-integrated grids, especially under renewable generation variability. To address the aforementioned shortcomings, this study presents a comprehensive analysis of EV integration impacts on power quality, supported by in-depth simulations as well as real-time observations. Simulations were carried out using Electrical Transient Analyzer Program (ETAP), Version 20.6, available at https://etap.com/product-releases/etap20-6-release. The new contributions of the proposed study are as follows:

-

1.

This paper presents a thorough analysis of power quality in an EV charging microgrid with harmonic distortions and voltage stability in various operating modes. Unlike other papers, which brush technical issues under the carpet, the current paper performs numerical analysis of how various EV charging setups impact the harmonic spectrum. Through an examination of various loading levels as well as on and off conditions of the chargers, this study uncovers the worst-case and best-case scenarios of power quality.

-

2.

This study employs the Electrical Transient Analyzer Program, known as ETAP, to conduct detailed simulations of a grid-connected microgrid with integrated EV charging stations. Through various operational scenarios, the research provides valuable insights into the performance of different system configurations, enabling optimized grid design and improved stability measures. Using ETAP, the study captures transient effects and non-linear load behavior with high fidelity.

-

3.

This study improves practical relevance by using the Volkswagen ID4 Crozz as a representative EV model, ensuring that all load parameters align with real-world specifications. This technique provides more precise data on the effect on the grid, including voltage distortion and harmonic distortion. Since the simulations are so correlated with actual EV behavior, the outcomes translate directly to actual-world deployment scenarios, enabling utilities and microgrid operators to design more effectively for and operate EV integration.

-

4.

The paper considers coordination between charging of EVs and renewables, i.e., photovoltaic panels and wind turbines, in a microgrid. As the paper includes models of renewable energy, it considers their combined effect on harmonics and voltage stability.

-

5.

A key contribution of this study is the verification that the EV-integrated microgrid operates within the harmonic limits outlined in IEEE STD 519–2014. All simulation results are assessed in accordance with this industry standard, which establishes acceptable thresholds for total harmonic distortion and individual harmonic order distortion in electric power systems. By designing and operating the system to align with IEEE 519–2014 criteria, the study validates the robustness of the model and proposed solutions.

Organization of the paper

The work is structured in eight sections to provide a comprehensive examination of the impact of EV integration on grid-connected microgrids from the perspective of power quality issues such as harmonic distortions. Section 2 describes the methodology, where the use of ETAP software for the modeling and simulation of the microgrid and the selection of the Volkswagen ID4 Crozz as the test EV model are described. Section 3 gives EV integration to the grid, discussing an overview of EV technology and the impact of EVs on the grid. Section 4 outlines system component models, and particular focus is given to harmonic components induced by EVs. Section 5 discusses thoroughly the exceptional harmonic components introduced by EVs. Section 6 outlines operation modes explored, designed for the purpose of emulating the impact of various configurations on power quality and grid stability. Section 7 gives the results and discussion, summarizing the findings from the simulations. Finally, Sect. 8 concludes with the summary of key findings, highlighting the contribution of the study and offering suggestions on how to enhance microgrid efficiency and stability.

Methodology

ETAP software is applied in this research for simulation and modeling the grid-connected microgrid. ETAP has extensive usage for the purposes of power system analysis and simulation and, as such, is also suitable for investigating the complex behaviors within a microgrid. Strong software features of high modeling and simulation ability are exploited for performing a detailed investigation of the behavior of the microgrid in different sets of circumstances. The research capitalizes on the diverse nature of ETAP to strategic effect, emphasizing the value of advanced system modeling and simulation. Scenarios under examination in this study span a set of operating conditions and provide a balanced perspective of microgrid operation. Examination of scenarios with diverse changes in RESs generation makes possible the insight of the response of the system in different conditions. Scenario evaluation with charging station usage supports the evaluation of the impact on the performance of the microgrid during peak demand or specific patterns of charging.

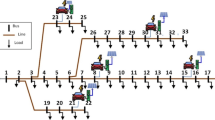

This approach is in accordance with the current industry trends and challenges, particularly in addressing the integration of RESs into current power systems. An integral component of the study is the meticulous analysis of potential power quality issues, voltage stability, and reliability risks likely to be triggered by the increased integration of RESs into the microgrid. This particular attention is essential in ensuring the robustness and sanity of the microgrid, especially considering that RESs are intermittent. The energy system combines PV and WECS to supply power to the loads and charging stations as shown in Fig. 1. The charging station itself is a research area, with a dual configuration where both DC and AC chargers are installed. The presence of a charging station, which is composed of DC and AC chargers, compels the system to be complex. It is termed a critical factor, particularly in terms of diversity in charging technology and its potential impact on microgrid operation. The research places great emphasis on investigating the complexity introduced by the charging station. Investigation is targeted especially on cases in terms of utilization of the charging points so that there is appropriate examination of microgrid resilience at peak load or given charging patterns.

A comprehensive analysis is performed to investigate the impact of EV integration in the grid on power quality with respect to harmonic distortions. The research employs a systematic framework by taking various operating conditions into account to bring out the profound impacts of EV integration on harmonics in the grid. EV integration is a dynamic parameter that can have a far-reaching impact on the electrical grid. When EVs are introduced into the grid, their charging behavior and application scenarios are diversified in a systematic manner to represent different operating conditions. This process enables the study to evaluate how EV integration impacts power quality, with special emphasis on harmonic distortion.

Harmonics, which refer to deviations from the standard sinusoidal waveform in the electrical system, can be influenced by the charging characteristics of EVs. The integration of EVs has the potential to introduce harmonic distortions into the grid, thereby affecting power quality. To assess these effects systematically, this study follows a four-step methodology, as illustrated in Fig. 2. Stage 1 carries out the initial assessment, i.e., grid interaction analysis, power quality concerns, climatological data, system configuration, and load estimation using ETAP software. Phase 2 is concerned with design optimization analysis, considering significant evaluation criteria such as power quality, load management strategies, and renewable energy exploitation with imposed model constraints such as battery state of charge (SOC), harmonic distortion limits, and renewable energy fractions. Various configuration possibilities are investigated, including various charging station configurations and various load levels. Phase 3 is under consideration for investigation by technical, economic, and environmental analysis. Power quality is investigated by harmonic orders, percentage distortion, and voltage waveform deviation, whereas economic issues are with cost implications of power quality issues. Environmental analysis is interested in renewable energy inputs and emissions savings. Stage 4 terminates the power quality assessment by defining the best harmonic suppression methods, voltage stability assessment, and electric vehicle charging network optimization. The ultimate aim is to define the best EV charging method to minimize harmonic distortion, maximize renewable energy management, enhance voltage stability at different loading conditions, and achieve IEEE 519–2014 compliance.

Use of the ETAP software is at the core of this analysis because it provides an interactive simulation platform through which one can scrutinize in-depth how the incorporation of EV affects harmonics in the grid. The proposed model with the unit of ETAP software is shown in Fig. 3. The DC chargers, as shown in Fig. 4, provide the outline for DC charging stations and individual charging units that are linked to a shared DC bus. The design for each unit is to receive various levels of power, thus performing efficiently and effectively in charging. The AC chargers, as shown in Fig. 5, demonstrate the structure of AC charging stations. They are fitted inside an AC bus and are designed to receive power demands for maximum EV charging capacity. The microgrid configuration in the figure is a highly synchronized system that makes use of RESs to provide energy requirements in the current era, such as charging stations for EVs. The use of circuit breakers and converters facilitates seamless control of the flow of energy, protecting the system components as well as power quality.

The BESS is a vital component for supply-demand balancing, storing excess energy and releasing it when needed. This mixed approach allows for the continuous and uniform operation of the microgrid, which is both effective and sustainable as an energy solution. Different operating conditions with fluctuations in EV charging patterns, such as peak loading or specific charging profiles, are investigated to ensure the full range of potential effects on the grid harmonics. Through systematic examination of the modes of operation, this study will provide a comprehensive insight into how the interaction between EVs and the power grid influences the power quality, with special focus on harmonics. The knowledge is significant to power system planners, operators, and stakeholders so they can address the challenges and opportunities that arise with increasing levels of EV adoption and the general shift toward sustainable power systems. Lastly, the research provides worthwhile contributions to the current debate on the integration of EVs into the grid and its implications for power quality.

EV integration to the grid

Overview of EV technologies

In recent times, there has been significant innovation in the manufacture of EVs, with a move towards cleaner and more efficient transport. EVs have branched out into numerous various forms, each characterized by a distinct technology and setup. In general terms, they can be broadly categorized into five types59:

-

Battery Electric Vehicles (BEVs).

BEVs are fully EVs that operate exclusively on electric power. BEVs are equipped with a sizable traction battery pack for storing electrical energy, along with an electric motor responsible for propelling the wheels. BEVs need to be plugged into an electric charging station to recharge their batteries. They are fully emission-free and famous for being environmentally friendly.

-

Plug-In Hybrid Electric Vehicles (PHEVs).

PHEVs integrate an internal combustion engine, usually gasoline-fueled, and an electric motor, with a battery, to enable propulsion. PHEVs are designed to operate on electricity alone for a significant distance, a distance that can be varied based on the model and the size of the battery. This allows drivers to cover short to medium distances entirely on electricity, reducing the demand for gasoline or diesel fuel during normal commuting or other normal driving conditions. Keep in mind that actual real-world fuel consumption of PHEVs can vary under real-world driving conditions.

The fuel economy figures quoted by car manufacturers are often based on standardized test conditions and may not necessarily correspond to the actual fuel economy achieved under real driving conditions. Driving style, road type, temperature, and rate of battery recharging are all factors that can influence actual fuel use. PHEVs can be charged via a standard electrical outlet or charging station and offer flexibility for both short and long trips. PHEVs provide a balance between electric-only driving and the extended range offered by the internal combustion engine. Their suitability depends on individual driving habits, access to charging infrastructure, and environmental considerations.

-

Hybrid Electric Vehicles (HEVs).

HEVs incorporate a normal internal combustion engine, along with an electric motor and a compact battery. HEVs are different from PHEVs in the sense that, they cannot be plugged into the grid to recharge. Unlike PHEVs, HEVs do not use power primarily from the internal combustion engine. The electric motor helps the engine during acceleration and can be used to recharge the battery through regenerative braking, which captures energy that would otherwise be lost during braking and converts it into electrical power. HEVs don’t require charging from an external source, such as a charging station or wall socket. They utilize the engine and regenerative braking to maintain the battery charged. HEVs tend to have a smaller battery capacity compared to PHEVs as a limiting factor on their ability to operate in electric-only mode.

HEVs are designed to maximize fuel efficiency through the use of the electric motor to assist the engine during acceleration and other driving conditions, hence reducing the operation of the internal combustion engine to a minimum.

-

Fuel Cell Electric Vehicles (FCEVs).

FCEVs use hydrogen to generate electricity by way of a fuel cell that powers an electric motor in return. The only emissions they produce are water vapor, and they typically enjoy greater driving distance than certain BEVs. FCEVs are far less prevalent and will require exposure to hydrogen refueling infrastructure. Refueling at a compressed hydrogen-filling station powers the FCEVs. Filling up an FCEV is as simple as filling up a gasoline- or diesel-driven car, with the process taking only a few minutes. However, refueling infrastructure may be a constraint for the FCEV owners in certain regions. FCEVs are being considered as a future solution to zero-emission transportation, particularly for applications where the large driving distances and rapid refueling are relevant. But expanding hydrogen refueling infrastructure and cleaner ways of producing hydrogen are necessary for mass FCEV adoption and the environmental acceptability of these vehicles overall.

-

Extended-Range Electric Vehicles (ER-EVs).

ER-EVs, or “range-extended” EVs, are a unique class of EVs that share some similarities with BEVs. ER-EVs are built on the same principles as BEVs and essentially rely on an electric motor powered by a massive battery pack for power. ER-EVs are equipped with an additional internal combustion engine (typically gasoline or some other similar fuel) that serves as a generator to charge the vehicle’s battery. The engine is not mechanically coupled to the wheels and does not aid in direct mechanical propulsion of the vehicle. When the battery charge falls below a point or when additional power is needed, the auxiliary combustion engine comes on and generates electricity to charge the battery. This boosts the driving range of the vehicle beyond that provided by the battery alone. ER-EVs can operate in all-electric mode when the battery is sufficiently charged. Such a mode offers zero-emission and quiet operation. ER-EVs are designed to reduce range anxiety, which is a concern for some owners of BEVs who worry that they will use up their battery power. Having the backup engine leaves a reserve source of power for long travel.

Impact of integrating EVs into the grid

Integration of EVs will have extensive consequences on various parts of the electrical grid, including power quality and grid stability. While EVs have numerous grid advantages, such as load management and grid stabilization, in certain situations they may turn out to be problems in power quality and stability within the grid. It may result in unstable demand for power during the charging phases and have implications for the continuity of power supplied to the customers. This is mainly applicable to communities with limited grid capacity or poor infrastructure. The ways in which EV integration will affect power quality and grid stability can be enumerated as below:

-

Voltage Fluctuations: Rapid charging of EVs at a dense site could create voltage fluctuations, especially if the grid infrastructure is poorly equipped to manage the higher load.

-

Harmonics: EV charging can result in harmonic distortion to the grid, affecting the quality of the supply of power. Harmonics can lead to equipment failure and increased losses in the grid.

-

Voltage Sags and Swells: High charging loads of EVs can lead to voltage sags (transient voltage drops) or voltage swells (transient voltage increases) if the grid infrastructure is not properly sized to handle the load.

-

Grid Resilience: While EVs can potentially enhance grid resilience through V2G capabilities, improper integration or a large number of discharging vehicles during grid outages can impact power quality.

-

Peak Load Impact: High concentrations of EVs charging simultaneously during peak hours can result in increased peak electricity demand, potentially requiring additional generation capacity and grid upgrades to maintain stability.

-

Grid Congestion: Grid congestion is conceivable where there is a high EV density, with a possibility of destabilizing the voltage and power quality.

-

Power Losses: As far as the charging stations’ efficiency and scheduling of charging of EVs are concerned, power losses in the grid are open to effect. Such power quality issues are countered through measures such as voltage regulation devices and advanced control systems, enabling an uninterrupted supply of electricity.

Models for system components

EV modeling using ETAP

EVs in ETAP software are simulated based on advanced battery models that reflect real-world EV battery pack behavior and capacity. For research in this research, the Volkswagen ID4 Crozz is used as the model EV because it is often driven by residents of the study area. ETAP provides a vast library of battery models to ensure proper simulation and analysis. To simulate the Volkswagen ID4 Crozz, a model of one of this library’s ternary lithium batteries is chosen. The chosen battery model with a capacity of 55.7 kWh best represents the Volkswagen ID4 Crozz battery pack specification to enable realistic simulation results that are relevant to real-world use. The ternary lithium battery has high energy density and is efficient and hence the optimum for use in duplicating the Volkswagen ID4 Crozz.

The selection is important in the research because it ensures that the impact of the EV on microgrid stability as well as power quality is well depicted. Table 1 gives a detailed description of the features of the Volkswagen ID4 Crozz, like battery capacity, charging rates, and other factors. Through the inclusion of these specific characteristics within the ETAP model, the research is able to simulate various modes of operation with high accuracy, examining how integration of the Volkswagen ID4 Crozz impacts power quality, particularly harmonic distortions, voltage stability, and overall grid reliability. This approach allows for a systematic analysis of EV-microgrid interaction and one that provides substantial information about challenges and advantages related to high EV penetration. Using a common model that is representative of actual EV specifications guarantees conclusions derived from the study are correct and relevant to industry practice and trends in the present.

Estimation of the EV population

The quantity of EVs in the study area is ascertained by considering the percentage of EV integration in the area. This ratio, which represents the percentage of EV integration, is computed by comparing the count of households that own EVs (\(\:{N}_{hhEV})\) to the overall residential units in the study region (\(\:{N}_{hh}\)) as represented in the following equation60:

The number of residential units within the study area is determined as follows:

Where \(\:{S}_{Thh}\)represents the total apparent power consumption of the residential units and \(\:{S}_{hh}\) represents the apparent power demand of an individual household.

The EV population in the study area is determined based on the overall apparent power demand of the loads. As previously indicated, the study network consists of a combination of both residential and commercial loads.

Battery energy storage system

Solar power is an RES and a clean energy, but it is highly variable. It depends on the time of day, weather, and location. It leads to fluctuations in output power. During periods of high solar radiation, there is surplus energy generation compared to demand, while during cloudy and nighttime periods, solar output is zero. Battery banks are required for generating a stable and consistent supply of power, especially in situations where the source of energy, e.g., solar radiation, is intermittent. They absorb excess power when available and release it when needed to generate a constant output of power to target loads. The battery bank size determines how much power can be stored and then delivered to the loads. Choosing the proper-sized battery bank is essential so that you have enough storage for as much energy as you need, to power your own special requirement, either backup power on a cloudy day or time-shifting excess generation of solar energy to night loads.

Battery bank capacity is the most significant parameter. It indicates how much energy the system can store and deliver to loads. DOD is the percentage of the stored battery energy that is expended in a single charge-discharge cycle and affects battery life. Battery life is a decisive factor in whether the energy storage system is economically viable. Batteries can have only a limited number of charge-discharge cycles before capacity and performance are degraded. The estimated battery life is an important factor in system design. The degree of discharge of a battery in use impacts its life. More discharging will have fewer numbers of charge-discharge cycles and less total battery life. Monitoring and controlling the DOD is necessary to ensure the best life and performance of the battery. SOC is a significant parameter in battery management. Proper estimation of SOC is crucial for effective operation and maintenance of the battery storage system. The BESS model takes into account numerous factors, such as the charge and discharge power, the rate of self-discharge, and the efficiency of charging and discharging, as described below61,62:

Where, \(\:{\varvec{E}}_{\varvec{B}\varvec{E}\varvec{S}\varvec{S}}^{\varvec{r}\varvec{a}\varvec{t}\varvec{e}}\) denotes rated capacity of the BESS in kWh, \(\:{\varvec{E}}_{\varvec{B}\varvec{E}\varvec{S}\varvec{S}}\left(\varvec{t}\right)\) denotes the capacity for BESS at time t in kWh, \(\:{\varvec{S}\varvec{O}\varvec{C}}_{\varvec{B}}\left(\varvec{t}\right)\:\)denotes the SOC for BESS at time t,\(\:\:{\varvec{\delta\:}}_{\varvec{s}\varvec{e}\varvec{l}{\varvec{f}}_{\varvec{D}}}\) denotes the self-discharging rate for BESS, \(\:{\varvec{\eta\:}}_{\varvec{B}\varvec{E}\varvec{S}{\varvec{S}}_{\varvec{C}\varvec{h}}}\) and \(\:\:{\varvec{\eta\:}}_{\varvec{B}\varvec{E}\varvec{S}{\varvec{S}}_{\varvec{D}\varvec{i}\varvec{s}}\:}\:\)denote the charging and discharging efficiencies of BESS, respectively, \(\:{\varvec{P}}_{\varvec{B}\varvec{E}\varvec{S}{\varvec{S}}_{\varvec{C}\varvec{h}}}\) and \(\:{\varvec{P}}_{\varvec{B}\varvec{E}\varvec{S}{\varvec{S}}_{\varvec{D}\varvec{i}\varvec{s}}}\) denote charging and discharging power for BESS in kW, respectively.

PV modelling

PV technology is a major driving force for converting sunlight to electricity using semiconductor material like silicon on solar panels to convert the light energy into direct electric power. Photovoltaic cells are the backbone of this technology, in which when hit by sunlight, photons are absorbed and electrons are driven, thus developing an electric current. Significantly, the efficiency of this conversion is inextricably linked with environmental conditions, and temperature influences performance. However, ongoing innovation in technology and material, as well as the grid integration of PV systems and use of energy storage technology such as batteries, has improved the reputation of solar energy. These advancements not only have improved the overall effectiveness of solar panels but have also helped in making solar power an affordable and universal source of electricity generation, which has been a big leap towards greenifying the energy industry. The quantity of electrical energy generated by a solar panel varies based on a number of parameters and can be calculated using the formula below63,64,65:

Grid modelling

As mentioned above, RESs produce power intermittently, and hence there are cases when the net power output of these units and BESS fails to meet the demanded load. In such situations, the utility grid is employed as a backup, providing power to the microgrid to meet the demand. The utility grid power-supplying model is described below:

Where, \(\:{\varvec{P}}_{\varvec{G}\varvec{r}\varvec{i}\varvec{d}}\left(\varvec{t}\right)\) denotes the power supplied by the grid, \(\:{\varvec{P}}_{\varvec{L}\varvec{o}\varvec{a}\varvec{d}}\left(\varvec{t}\right)\) represents the load power and \(\:\:{\varvec{P}}_{\varvec{B}\varvec{E}\varvec{S}\varvec{S}}\left(\varvec{t}\right)\) represents the power provided by BESS.

Harmonic components generated by EVs

EVs are gaining increasing popularity, and their integration into microgrids raises some interesting considerations, particularly in terms of harmonic components and power quality. Harmonic components are sinusoidal voltage or current waveforms with frequencies that are integer multiples of the fundamental frequency. EVs are typically powered by power electronic converters that can inject harmonics into the microgrid. The chargers are normally connected to the grid, and the injected harmonics have the potential to affect power quality. EVs also utilize power electronics for battery charging, DC-AC inversion in hybrid and EVs, and motor control. The power electronics can inject harmonic distortion into the grid since they are non-linear. The frequency and amplitude of harmonic components from EVs depend on charging infrastructure type, power electronics, and EV design. EVs employ inverters to transform the battery’s DC power to AC power to power the electric motor.

The inverters, by their switching operation, can produce harmonics in the microgrid. The order and amplitude of harmonics are determined by the inverter configuration and the modulation strategy. When a number of EVs are charging from a microgrid, unbalanced load currents and unbalanced loads can be present, and they can inject harmonic components. Unbalanced loads can produce harmonics, particularly in the zero-sequence (neutral current) components. EVs that are charging from a microgrid can get coupled with the existing grid harmonics. If the grid already contains harmonic distortion, the EVs can compound the issue by introducing more harmonics into the system. There are regulations and standards in most countries to restrict the level of harmonic distortion within the power grid. These regulations are applied to all devices that are connected to the grid, including EVs and charging stations. Adherence to these standards is important in order to provide power quality. Excessive harmonic components can lead to negative impacts on other microgrid elements, such as transformers and capacitors. Components are subjected to additional stress and heating by harmonics that can reduce their life expectancy.

Harmonic components in waveforms of current are greater than in voltage waveforms, and the percentage of total harmonic distortion (THD) plays a major role in impacting power quality of microgrids. This is of specific significance in EV charging stations. The increasing use of EV non-linear loads can disturb the sinusoidal nature of voltage and current signals because these non-linear waveforms consist of harmonic components. AC/DC and DC/AC converters of EV charging systems are some of the prominent sources of such harmonics. EVs, driven by electric motors and battery banks, possess notable environmental advantages in the form of zero emissions and renewable energy sources, thereby reducing dependence on fossil fuels. Harmonics in the power system can lead to a variety of risks in a smart microgrid:

-

Overheating of Power Distribution Lines: Harmonics can result in excessive heat generation in power distribution lines, leading to increased losses, reduced efficiency, and even potential harm to the electrical infrastructure.

-

Resonance in Smart Microgrid: Effects of resonance may be caused within the smart microgrid through harmonics, causing interference to the stability and performance of the microgrid. This equipment damage and voltage and current distortion are other alternatives provided by resonance.

-

Reduced Transformer and Electric Equipment Life: Harmonics shorten the life of transformers and electric equipment installed on the microgrid, leading to future premature failure and increased maintenance.

-

Reactive Capacitor Damage: Destructive effects may be induced on reactive power compensating capacitors by harmonics, which will destroy the capacitors. The process will decrease power factor correction as well as system efficiency.

-

Protection Switch Tripping: Harmonic current may result in premature or unjustified tripping of the protective switches of the microgrid, leading to microgrid operation instability and finally power interruption.

-

Communication Infrastructure Disturbance: Harmonics can lead to noise or interference within the communication infrastructure of the smart microgrid, impacting the reliability and performance of communications networks utilized for monitoring and control.

THD is a typical parameter that can be utilized in order to quantify the extent of harmonic distortion in smart microgrids. \(\:{\varvec{T}\varvec{H}\varvec{D}}_{\varvec{V}}\) refers to a measure used to measure the overall distortion of the voltage waveform within a microgrid. The measure of \(\:{\varvec{T}\varvec{H}\varvec{D}}_{\varvec{V}}\) is typically taken as a percentage and represents the quality of the voltage supply within the microgrid. A lower percentage of \(\:{\varvec{T}\varvec{H}\varvec{D}}_{\varvec{V}}\) defines a purer and cleaner sinusoidal voltage waveform, while a higher percentage of \(\:{\varvec{T}\varvec{H}\varvec{D}}_{\varvec{V}}\) indicates that there is a greater level of harmonic distortion, and this can lead to equipment failure and power quality issues in the microgrid. It is required to monitor and maintain \(\:{\varvec{T}\varvec{H}\varvec{D}}_{\varvec{V}}\) at low levels to ensure a stable and safe electric supply in smart microgrids. It is determined by analyzing the harmonic components of the voltage signal with respect to the fundamental frequency. Mathematically, \(\:{\varvec{T}\varvec{H}\varvec{D}}_{\varvec{V}}\) is determined by the formula66:

Where, \(\:{\varvec{V}}_{\varvec{n}}\) represents RMS voltage of \(\:{\varvec{n}}_{\varvec{t}\varvec{h}}\) harmonic, \(\:{\varvec{V}}_{1}\) represents the magnitude of the fundamental frequency component of the voltage waveform.

Current Total Harmonic Distortion (\(\:{\varvec{T}\varvec{H}\varvec{D}}_{\varvec{I}}\)) is one of the significant measurements, which is used to ascertain what percentage of the harmonic distortion has the current waveform of an electricity system. It measures the way the current waveform deviates from the ideal sinusoidal waveform. The \(\:{\varvec{T}\varvec{H}\varvec{D}}_{\varvec{I}}\) is normally expressed in percentage. The smaller the percentage of \(\:{\varvec{T}\varvec{H}\varvec{D}}_{\varvec{I}}\), the nearer the current waveform will be to an ideal sinusoidal waveform, which indicates good power quality. Conversely, the higher the percentage of \(\:{\varvec{T}\varvec{H}\varvec{D}}_{\varvec{I}}\), the more the harmonic distortion of the current waveform, and this has negative effects on the power distribution system, such as increased losses, overheating, and the potential to damage sensitive equipment. \(\:{\varvec{T}\varvec{H}\varvec{D}}_{\varvec{I}}\) is calculated using the formula:

\(\:{\varvec{I}}_{\varvec{n}}\) represents the effective current of \(\:{\varvec{n}}_{\varvec{t}\varvec{h}}\) harmonic, \(\:{\varvec{I}}_{1}\) represents the fundamental frequency component of the current waveform.

Effect of EV charger operation on harmonic dynamics

EV charging stations are becoming increasingly widespread in modern power systems, and their integration into microgrids introduces new challenges, particularly in terms of power quality. Among these, harmonic distortion is a significant concern due to the nature of EV chargers as nonlinear loads. However, it is not only the presence of chargers that matters. The operational settings and technical configurations of these chargers play a decisive role in determining the level and characteristics of harmonic distortion they inject into the grid.

One of the primary factors influencing harmonic emissions is the type of charger employed. Level 1 and Level 2 AC chargers generally operate with single-phase or three-phase rectifiers that introduce lower-order harmonics, especially the 3rd, 5th, and 7th. These harmonics arise due to the switching action of diodes or thyristors in uncontrolled or semi-controlled rectifier configurations. Meanwhile, DC fast chargers employ more complex converter topologies, such as two-level or three-level inverters combined with high-frequency switching. These systems are capable of injecting both low-order and high-order harmonics, depending on their switching strategy and load conditions. The faster the charger delivers power, the more rapidly its power electronics must switch, which in turn broadens the spectrum of harmonics generated.

Another critical aspect is power factor correction (PFC). Many modern EV chargers are equipped with PFC circuits, either passive or active. Passive PFC typically includes inductors and capacitors that smooth out current waveforms to reduce harmonic content. Active PFC, which uses power electronic converters, can dynamically shape input current to mimic a sinusoidal waveform. Chargers without any form of PFC tend to draw highly distorted current waveforms, especially at partial loads. The presence or absence of PFC, along with its implementation quality, significantly alters the THD and the harmonic current spectrum.

Switching frequency and modulation technique are also important contributors. Chargers that use pulse-width modulation (PWM) with lower switching frequencies tend to concentrate energy in the lower harmonic orders, which have a more detrimental effect on voltage quality and equipment lifespan. On the other hand, chargers using high-frequency PWM spread the harmonic energy over a wider range of higher-order harmonics, which are often easier to filter but may pose challenges for electromagnetic compatibility. The choice of modulation strategy, such as sinusoidal PWM or space vector modulation, impacts not only the efficiency and control performance of the charger but also the shape of the current waveform and harmonic content.

SOC of the EV battery also influences the harmonic behavior. At lower SOC levels, the battery demands higher charging currents, leading to greater distortion. As charging progresses and the battery nears full capacity, the current demand diminishes and the charger transitions into constant-voltage mode, often resulting in different harmonic patterns. This dynamic behavior introduces time-varying harmonic characteristics, which complicates the prediction and management of harmonics in real-time grid operations.

Operational coordination among chargers introduces another layer of complexity. In public or fleet charging stations, multiple chargers may operate simultaneously. If they are uncoordinated, each charger may start or stop independently, creating random harmonic superpositions. Moreover, if chargers operate on the same or similar switching frequencies without phase-shifted control strategies, they may produce harmonic resonance or amplification at certain frequencies. Even chargers from different manufacturers may have unique harmonic signatures due to proprietary control algorithms, resulting in intermodulation harmonics when used in the same location.

User behavior and environmental conditions also influence harmonic levels. Peak-hour charging, especially in residential areas where many users plug in vehicles at the same time in the evening, can create clusters of harmonic generation. Additionally, climatic factors such as ambient temperature can affect charger efficiency and internal thermal management systems, indirectly influencing their switching characteristics and, consequently, their harmonic output.

Furthermore, smart charging algorithms and demand-side management strategies can significantly mitigate or worsen harmonic issues. Chargers that implement delayed start, power throttling, or adaptive current control based on grid signals can help in reducing harmonic surges. In contrast, unmanaged or opportunistic charging, where vehicles begin charging at maximum capacity as soon as they are plugged in, is likely to cause significant harmonic spikes.

The harmonic impact of EV charging infrastructure is not only a function of the number of vehicles or chargers connected to the grid, but also of the intricate and dynamic operational behaviors of those chargers. Detailed modeling of these behaviors, along with coordinated grid control strategies, is essential to accurately assess and mitigate harmonic pollution in EV-integrated power systems. Future research should focus on developing standardized harmonic profiles for charger types, advancing harmonic-aware scheduling strategies, and designing robust grid monitoring systems that account for the evolving nature of EV charging operations.

Moreover, selective disconnection of EV chargers represents a promising operational strategy for mitigating harmonic distortion in modern power systems. In large-scale charging infrastructures, simultaneous operation of multiple chargers can result in the aggregation of harmonic currents, especially if these chargers share similar switching frequencies or modulation techniques. This overlap can lead to constructive interference, harmonic amplification, or even resonance at specific harmonic orders, particularly in weak or lightly damped distribution systems. By implementing selective disconnection protocols, system operators can disconnect specific chargers based on their harmonic contribution, operating phase, or real-time power quality indices.

This approach can be particularly effective during peak charging periods, where the harmonic load is elevated due to high utilization of chargers. For instance, disconnecting chargers with poor power factor correction, high THD, or those operating on harmonically sensitive buses can help flatten the overall harmonic spectrum and improve voltage waveform quality. Additionally, this strategy can be integrated with other demand-side management measures, allowing for dynamic reallocation of charging load while minimizing power quality impacts. Advanced control systems equipped with harmonic analyzers and real-time monitoring can support automated decision-making processes for charger disconnection and reconnection. These systems can assess the harmonic contributions of individual chargers and apply rule-based or optimization-based algorithms to determine the optimal subset of active chargers that balances energy demand with power quality requirements. In this context, the integration of machine learning and predictive analytics may further enhance the responsiveness and effectiveness of selective disconnection strategies by anticipating harmonic trends and proactively managing charger operation.

Ultimately, the selective operation of EV chargers offers a practical, scalable, and low-cost method to address the growing challenge of harmonic distortion in EV-integrated grids. When combined with smart scheduling algorithms and coordinated grid control, this approach contributes to a more stable and resilient energy infrastructure, capable of accommodating high penetration levels of electric mobility.

Studied operational scenarios

To analyze the effect of EV integration on grid power quality for harmonic distortions, some operating scenarios were defined. The operating scenarios vary ratios of loads, AC chargers, and DC chargers to assess their effect on the microgrid. The primary purpose is to use ETAP software to identify and implement solutions filtering out harmonics, enhancing power quality, and optimizing load flow for smooth microgrid operation. Every scenario presents other configurations to compare their impact on energy consumption and network load. The scenarios include an in-depth study of charger configuration versus attendant energy consumption. Load management and strategic disconnection reveal a nonlinear effect between the energy consumption at a station and charging chargers quantity. Peak load management is the most critical factor towards the success of energy efficiency and a healthy charging system, with power quality optimization and grid stability.

-

Scenario 1: AC Stations Off.

AC chargers are turned off here. Here, the intention is to study the impact of having only DC chargers on the microgrid’s power quality. In this case, there is an awareness of how the lack of AC charging generates harmonic distortions and the grid’s general performance.

-

Scenario 2: DC Stations Off.

This situation involves the closure of all the DC chargers, with AC chargers standing alone to work. The idea is to observe the levels of power quality and harmonic distortion when DC charging is not used. It provides an understanding of how the grid looks like when there are only AC chargers in operation.

-

Scenario 3: Full Load (100%).

AC and DC charging are both charged to capacity in this instance, a station maximum load case. This is a comparison point for observing worst-case energy consumption and harmonic distortion, an end-to-end picture of the microgrid at the top loads.

-

Scenario 4: 60% Load.

The load is reduced to 60% of the peak capacity by intentionally disconnecting half of the chargers. This case helps to determine the effect of partial load operation on power quality and grid stability. It analyzes how minimizing the load can optimize system performance and minimize power quality issues.

-

Scenario 5: 40% Load.

The load is then brought down to 40% of the total capacity. The aim is to explore the effect of degree load reduction on microgrid operation, primarily power quality and energy efficiency, and harmonic distortions. It evaluates the effectiveness of aggressive load management techniques in maintaining power quality.

Results and discussion

The section provides a comprehensive discussion of grid-connected microgrid and operation of an EV charging station. Various situations were taken into account for evaluating the impact of various operation conditions on power quality, harmonic distortion, and voltage stability. The simulation results obtained from the ETAP software under consideration of voltage waveform, harmonics orders, and voltage spectrum for various scenarios are discussed elaborately. To investigate the impact of EV integration into the grid on power quality, specifically on harmonic distortion, some simulation scenarios have been performed. Five operation scenarios have been designed, with various amounts of loads, AC chargers, and DC chargers. The distortion of voltages imposed in this study adhere to the IEEE STD 519–2014 standards, which provide acceptable individual harmonic distortion and THD values for different voltage levels at the point of common coupling (PCC). The limits are listed in Table 2.

Scenario analysis

-

i.

Scenario 1: AC Stations Off.

Scenario 1 identifies the challenges that the microgrid faces in the case of shutting down AC stations. The significant harmonic distortion levels observed in this scenario reflect the need for appropriate load management, efficient system design, and advanced monitoring systems such that the microgrid follows correct power quality standards. These issues need to be addressed in order to ensure the reliability, efficiency, and lifespan of the microgrid equipment. The conclusions emphasize that harmonics not only affect power quality but also create other impacts on system operation and maintenance. Figure 6 illustrates the voltage waveform with respect to time for Scenario 1, where AC stations are turned off. The waveform shows large fluctuations, representing harmonic distortions.

The distortions are caused by the nonlinear loads created by the EV charging stations. The waveform shows deviation from the pure sinusoidal shape, with clear peaks and troughs typical of harmonics. The waveform amplitude is highly fluctuating, with both greater and lesser peaks compared to those of a pure sinusoidal waveform. Such oscillations are typical of harmonic interference, which is typically present in systems with high non-linear loads, e.g., EV chargers. The waveform shape is a deformed waveform with high distortion from the ideal sinusoidal waveform. Distortion is caused by the harmonics produced due to the nonlinear loads of the EV charging stations. The fundamental cycle is not altered, but the occurrence of harmonics provides variability in each cycle and affects the voltage stability.

Table 3 presents a comprehensive analysis of harmonic voltage distortion across four major buses in the microgrid under Scenario 1, where all AC charging stations are switched off. The buses include the main loads bus at 0.40 kilovolts, the WT bus at 4.16 kilovolts, the grid bus at 0.40 kilovolts, and the PV bus at 0.60 kilovolts. The voltage spectrum is analyzed across various harmonic orders, ranging from the 1 st to the 49th, focusing on identifying the dominant harmonics and assessing their compliance with the IEEE standard 519–2014.

Among all harmonic orders, the fifth harmonic exhibits the highest magnitude, recorded at 0.7935% on both the main loads and grid buses. This value is notably higher than that on the WT bus and the PV bus, which show 0.4438% and 0.4191% respectively. The prominence of the fifth harmonic is characteristic of non-linear loads and power electronic converters, particularly those found in EV charging stations, which often operate using six-pulse rectifiers. The slightly lower values at the generation-side buses, such as the WT and PV buses, indicate that harmonic propagation is more significant near load centers than at generation points. Despite being the most dominant, the fifth harmonic remains well below the IEEE 519–2014 individual limit of 5%, indicating that the microgrid maintains harmonic levels within acceptable boundaries. Another significant component is the eleventh harmonic, with values of 0.6338% at both the main loads and grid buses, 0.5604% at the WT bus, and 0.5451% at the PV bus. The presence of this harmonic is likely due to resonance phenomena and the cumulative interactions between non-linear sources distributed throughout the microgrid. The eleventh harmonic is not typically as dominant in simple systems, but in interconnected renewable-based microgrids with varying impedance and multiple converter interfaces, it becomes more pronounced. Again, all values remain within IEEE-recommended limits.

The thirteenth harmonic also appears with non-negligible magnitudes across all buses, ranging from 0.3529 to 0.4321%. While lower than the fifth and eleventh, its consistent presence confirms that multiple harmonic orders are actively propagating in the network. These medium-order harmonics, if left uncontrolled, can lead to voltage waveform distortion and degradation in the performance of sensitive electronic devices. The third and seventh harmonics show relatively minor distortion, with values around 0.0642–0.1850% depending on the bus. These lower-order odd harmonics generally arise from asymmetrical loading or line impedance mismatch and are also influenced by system grounding. Their minimal values reflect effective load balancing and grounding practices in the model. For harmonic orders above the fifteenth, the voltage spectrum shows a clear declining trend. The seventeenth harmonic registers up to 0.1995%, and subsequent harmonics such as the nineteenth, twenty-third, twenty-fifth, and so on, reduce progressively below 0.07%. By the time the system reaches the forty-ninth harmonic, distortion is as low as 0.0084%. This tapering off of higher-order harmonics is expected due to natural attenuation in the system and the frequency-selective impedance of transformers and lines, which suppress high-frequency components. These results also suggest that no resonant conditions exist that would otherwise amplify specific high-order harmonics.

A comparison across the four buses reveals a consistent pattern. The main loads and grid buses typically exhibit the highest harmonic distortion values, indicating that these points are the most exposed to non-linear load effects. This observation is particularly relevant for microgrid planners, as it highlights the need for local harmonic filtering or improved converter designs at the load end. In contrast, the WT and PV buses, which represent renewable generation points, experience comparatively lower harmonic content. This pattern confirms that harmonic propagation in microgrids is directional and that loads are the principal sources of distortion. Overall, all harmonic levels recorded in Table 3 fall well within the individual harmonic distortion limit of 5% and the THD limit of 8% defined by IEEE standard 519–2014 for voltage levels below 1 kilovolt. Although the total THD is not explicitly presented in this table, the low values across all harmonic orders suggest that the aggregate THD remains well below the threshold.

Scenario 1 effectively demonstrates the capability of the proposed model to manage harmonic distortion even in the presence of non-linear loads, and without the influence of active AC stations. The data shows that harmonic emissions from EV charging infrastructure and power electronics are well controlled through embedded control strategies, appropriate network impedance design, and possibly passive or active filtering mechanisms. This level of performance indicates a high degree of robustness and reliability in the microgrid model and supports its suitability for real-world applications where power quality is critical. The findings of Table 3 validate the model’s strength in harmonic suppression, system resilience, and adherence to regulatory standards. These attributes are essential for ensuring the stable and efficient operation of microgrids integrating renewable energy sources and modern electric loads.

-

ii.

Scenario 2: DC Stations Off.

Scenario 2 shows the results when DC stations are turned off. This scenario is important for understanding the impact of the absence of DC charging stations on the microgrid’s performance. Figure 7 shows the voltage waveform for Scenario 2, where DC stations are off. The voltage variations indicate the system’s response to the absence of DC charging stations, which affects the harmonic distortions and overall power quality. Similar to Scenario 1, the amplitude of the waveform in Scenario 2 exhibits significant variations, indicating harmonic presence. The model is well representing these variations, demonstrating its potential for reflecting the real-world consequences of different operation conditions. The waveform is also distorted, but the pattern of distortion is a bit different than Scenario 1 due to the changing nature of loads (absence of DC stations). The distinction verifies the model’s responsiveness to changing types of loads. The consequences of harmonics introduce additional oscillations in each cycle, which influence voltage stability.

Table 4 provides a detailed overview of the harmonic voltage distortion across four key buses in the microgrid under Scenario 2, where all DC charging stations are deactivated. The buses analyzed include the main loads bus operating at 0.40 kilovolts, the WT bus at 4.16 kilovolts, the grid bus at 0.40 kilovolts, and the PV bus at 0.60 kilovolts. Harmonic analysis was conducted across a wide range of odd harmonic orders, from the third up to the forty-ninth, with the fundamental frequency excluded. A dominant characteristic observed in this scenario is the significant amplitude of the fifth harmonic component. Both the main loads and the grid bus report a maximum distortion of 0.9762% at this harmonic order, making it the most pronounced distortion across the system. The WT bus and PV bus also show notable fifth harmonic content, registering 0.4975% and 0.4443% respectively. The elevated level of the fifth harmonic is strongly associated with the non-linear operation of EV charging systems and other power electronic interfaces, such as inverters, rectifiers, and variable speed drives. These components are known sources of low-order harmonics due to their switching behavior.

Despite the relatively high magnitude of the fifth harmonic in Scenario 2 compared to Scenario 1, it remains significantly below the individual harmonic distortion limit of 5% as prescribed by the IEEE standard 519–2014. This compliance demonstrates the capacity of the model to maintain power quality, even under conditions where DC charging infrastructure is unavailable and non-linear load interactions become more concentrated at the alternating current (AC) end of the system. The eleventh harmonic represents another significant distortion component. The main loads and grid bus both record distortion levels of 0.6346% at the eleventh harmonic, with the WT bus and PV bus registering 0.5522% and 0.5385% respectively. This harmonic is not typically associated with isolated single sources, but rather with complex interharmonic interactions, system resonances, and the aggregated effect of distributed non-linear devices. Although the values are lower than the fifth harmonic, they are consistent across all buses, indicating a network-wide propagation of this component. Once again, all values remain comfortably within the IEEE-defined individual limits, ensuring no breach of voltage waveform quality.

The thirteenth harmonic follows a similar trend, showing voltage distortions in the range of 0.3303–0.4250% across all buses. The presence of this medium-order harmonic is noteworthy as it often arises due to switching overlap in converters and the harmonic multiplication effects of interlinked non-linear sources. While not as impactful as the fifth and eleventh harmonics, its non-negligible magnitude points to a layered harmonic profile within the microgrid, demanding careful monitoring and control. Lower-order harmonics such as the third and seventh also appear in the results. The third harmonic, while minimal at the main loads and grid buses (0.0641%), reaches up to 0.3918% at the PV bus. This is indicative of the presence of triplen harmonics, which may accumulate in neutral lines and are typically generated by single-phase non-linear loads or unbalanced three-phase systems. However, the values remain low enough to suggest that phase imbalance and zero-sequence harmonic propagation are not critically affecting the microgrid in this scenario.

The seventh harmonic records moderate levels across all buses. The main loads and grid buses show distortion of 0.2103% each, while the WT and PV buses display 0.1962% and 0.1935% respectively. These values, although measurable, are well below the 5% limit and pose little risk to system stability or equipment functionality. Higher-order harmonics beyond the fifteenth order exhibit a clear pattern of exponential decay in magnitude. The seventeenth harmonic is the last notable one, with values around 0.2015% at the main loads and grid buses, and slightly lower at the WT and PV buses. From the nineteenth to the forty-ninth harmonics, distortion levels continue to decrease, falling below 0.15% in all instances. For example, the twenty-fifth harmonic measures approximately 0.0368% at the main loads, and even the forty-ninth harmonic is reduced to just 0.0093%. This attenuation pattern reflects the natural impedance filtering effect of the network, and possibly the presence of designed passive filters or careful layout of cable and transformer configurations to suppress high-frequency harmonic propagation.

A comparative review between the different buses confirms that the main loads and grid buses experience the highest distortion levels. These buses, being the primary delivery points for consumer power and the connection points for downstream non-linear loads, are more exposed to harmonic interference. On the other hand, generation-side buses such as the WT and PV points demonstrate lower harmonic penetration, reinforcing the directional nature of harmonic flow and the local generation-load dynamics in microgrids. Importantly, all harmonic magnitudes in Table 4 fall within the permissible limits defined by IEEE standard 519–2014, which stipulates that the total harmonic distortion in voltage for systems below one kilovolt should not exceed 8%, and individual harmonic components should be kept below 5%. Although the total harmonic distortion value is not provided explicitly in the table, the cumulative sum of individual harmonic contributions suggests that THD remains safely under this threshold. The highest individual harmonic value recorded is the fifth harmonic at 0.9762%, which is less than one-fifth of the permissible maximum.

Scenario 2 successfully demonstrates the model’s capability to suppress harmonic distortions despite the absence of DC charging stations. Typically, DC charging systems with high-speed converters are major sources of harmonics; yet, their deactivation in this scenario shifts harmonic burden to other non-linear AC-based devices. The fact that the system continues to perform within compliance parameters illustrates the model’s effective harmonic mitigation strategy. This is crucial for maintaining voltage waveform quality, preventing overheating or malfunction in sensitive equipment, and ensuring operational continuity of protection systems.

In conclusion, the results presented in Table 4 confirm the resilience and stability of the microgrid model in managing harmonics under real-world-like operating conditions. The ability of the model to remain within IEEE standard thresholds, even in a high non-linear load environment without the support of DC charging regulation, showcases its reliability, adaptability, and readiness for deployment in modern microgrids that integrate renewable energy and electrified transport infrastructure.

-

iii.

Scenario 3: Full Load.

Scenario 3 examines the behavior of the microgrid when both AC and DC EV charging stations are operating concurrently at their maximum rated capacity. This scenario simulates the most demanding condition, where the charging infrastructure introduces the highest possible load on the system. In this context, the contribution of EV charging stations to power quality issues becomes most pronounced, particularly in terms of harmonic distortion. EV charging stations are a major source of harmonic distortion due to the use of power electronic interfaces, including rectifiers, inverters, and DC-DC converters. These components exhibit nonlinear behavior by drawing current in short pulses rather than in a smooth sinusoidal manner. As a result, they inject harmonic currents into the grid, leading to distortion of the voltage waveform across the entire network. The severity of this distortion increases proportionally with the number of chargers in use and their rated capacity, both of which are maximized in this scenario.

At full load, each charging unit operates at its maximum switching frequency, which intensifies the generation of harmonics, particularly in the lower orders such as the 3rd, 5th, 7th, and 11th. These harmonics are reflected back into the grid and affect voltage and current waveforms at all nodes. The superposition of multiple harmonic sources from simultaneously charging EVs leads to harmonic resonance, waveform notching, and voltage flattening, which collectively degrade power quality. This is particularly problematic at the point of common coupling, where the aggregation of harmonic sources results in elevated THD levels. Figure 8 presents the voltage waveform during full load conditions. The waveform exhibits evident deviation from the ideal sinusoidal shape, with exaggerated peaks and valleys indicating significant waveform distortion. This distortion arises from cumulative nonlinear loading by multiple high-power EV chargers operating simultaneously.The presence of such distortions confirms that EV charging stations, particularly when operating in large numbers and at full capacity, are dominant contributors to harmonic pollution in the microgrid.

Table 5 provides a detailed breakdown of harmonic content for this scenario. The results show that the 5th harmonic distortion is 0.72% and the 11th harmonic distortion is 0.63% at the main loads and grid bus. These values are the highest among all five evaluated scenarios. The 5th harmonic is especially significant because it is commonly produced by six-pulse rectifiers used in most Level 2 and DC fast chargers. The 11th harmonic is often associated with high-frequency switching in inverters and pulse-width modulation techniques. The fact that these two harmonics dominate the distortion profile under full-load conditions highlights the role of EV charger electronics in generating repetitive waveform deviations. Compared to Scenario 4, which uses only 60% of the charging infrastructure, the full-load scenario presents noticeably higher harmonic levels. The marginal increases may appear numerically small, but even slight percentage increases in lower-order harmonics can produce substantial electromagnetic interference, voltage flicker, and overheating of system components such as transformers and neutral conductors.

WT AC bus and PV AC bus also register increased harmonic levels at 0.42% and 0.41% respectively for the 5th harmonic, and 0.56% and 0.55% respectively for the 11th harmonic. These measurements reflect the distributed impact of EV-induced harmonics throughout the microgrid. The 7th harmonic remains low at all buses, with values ranging from 0.14 to 0.18%. Although these higher-order harmonics are less severe, they still indicate the broader harmonic spectrum caused by high switching frequencies. The consistent presence of harmonics across the microgrid nodes indicates that distortion from EV chargers is not localized but diffuses system-wide through coupling paths. These findings strongly support the conclusion that EV charging stations, especially when operating at full load, are not only active sources of harmonics but also dominant contributors to power quality deterioration in interconnected microgrids. This underscores the need for careful consideration of EV load modeling, harmonic behavior, and system-wide impacts during microgrid planning and operation. Moreover, understanding the harmonic signature of EV chargers is essential to maintaining compliance with standards such as IEEE STD 519–2014, ensuring voltage quality, and avoiding long-term equipment degradation.

-

iv.

Scenario 4: 60% Load.

Scenario 4 examines the system performance under the 60% capacity load. The partial load condition allows for the examination of the behavior of the microgrid under a modest loading condition. Figure 9 illustrates the voltage waveform as a percentage versus time (cycle) for scenario 4, portraying the voltage stability and oscillations faced under the 60% load condition. This is a key observation since it illustrates the ability of the system in maintaining stable voltage levels despite the variation in the load. In this instance, the voltage waveform undergoes minimal fluctuations, showing that the microgrid is able, in most instances, to maintain voltage stability with medium load levels. These fluctuations, although minimal, are significant to note since they may affect the performance of sensitive equipment connected to the grid. Voltage stability is among the performance measures, and any deviation from the nominal voltage can be a sign of issues with the microgrid’s ability to process the load efficiently. The variations in voltage observed are within acceptable limits as per the IEEE STD 519–2014 standards. These standards stipulate that at voltages less than 1.0 kV, THD should be lower than 8%, and individual harmonic distortion should be lower than 5%.The findings indicate that the microgrid performs well within these specifications, demonstrating its feasibility to drive a 60% load without significantly deviating from the standard voltage levels. The stability in voltage waveform, as noted, contributes to overall power quality. Steady voltage levels minimize the threat of equipment breakdown and enhance power delivery efficiency.