Abstract

To investigate the evolution mechanism of rock mechanical properties under high-stress conditions, marble samples from deep underground were selected for a series of triaxial compression tests, microscopic fracture surface scanning, and discrete element numerical simulations. The results indicate that significant changes in the mechanical properties of marble occur when the confining pressure exceeds 30 MPa. Under low confining pressure conditions, the stress-strain curve of the rock exhibits relatively weak post-peak deformation capacity. As the confining pressure increases, the peak strength of the rock increases significantly, while the elastic modulus remains relatively stable. The rock exhibits low cohesion and high internal friction angle. Under high confining pressure conditions, the stress-strain curve demonstrates more ideal plastic deformation characteristics. As the confining pressure increases, the increase in peak strength becomes less pronounced, while the elastic modulus rises. The rock exhibits high cohesion and low internal friction angle. Analysis of the fracture surface morphology shows that under high confining pressure, the failure mechanism of the rock gradually shifts from primarily grain boundary cracking to predominantly transgranular fracture. The microscopic differences in the internal fracture mechanism of the rock are the key factors driving the evolution of its mechanical properties.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The utilization of deep underground space for large-scale energy storage has emerged as a dominant global strategy for energy reserves, playing a critical role in safeguarding national energy security, securing strategic material supplies, and advancing the achievement of carbon peaking and carbon neutrality goals1,2. In the field of deep underground engineering, rock strength and failure characteristics are the basis for theoretical calculations and design work3,4. Studying the deformation and failure characteristics of rocks under high-stress conditions is of significant reference value for deep tunnel support, mining microseismic monitoring, and rock burst early warning5,6,7.

Under triaxial compression, with the increase in confining pressure, the failure mode of rocks gradually transitions from brittle failure to ductile failure. Under low confining pressure, rocks exhibit distinct peak strength and typical brittle failure characteristics. However, under high confining pressure, the peak strength of the rock no longer increases significantly and forms a clear shear band, with the failure mode shifting to ductile failure8,9,10. Additionally, under triaxial compression, with the increase in confining pressure, the peak strength, residual strength, elastic modulus, and deformation modulus of the rock all show a linear growth trend, while the dip angle of the rock shear failure band gradually decreases11,12. In the brittle-ductile transition stage, rocks may simultaneously exhibit both shear failure and cataclastic flow as failure modes. With an increase in the average particle size, the critical confining pressure required for the brittle-ductile transition is significantly reduced13,14. It is generally believed that under low confining pressure, stress within the rock is mainly concentrated in limited, low-strength regions, resulting in clear strain-softening behavior. In contrast, under high confining pressure, even materials with higher internal strength will reach their bearing limit, leading to more uniform yielding and weakening deformation, and thus showing obvious plastic deformation characteristics. Research indicates that large deformation plastic failure modes frequently occur in surrounding rock within deep, high-stress environments, posing significant challenges for the design of support structures15.

Under triaxial compression, with the increase in confining pressure, the shear strength of the rock exhibits nonlinear characteristics16,17. Specifically, as confining pressure increases, the cohesion of the rock material continuously increases, while the internal friction angle gradually decreases18. Under low confining pressure, the rock primarily exhibits tensile failure, with fracture surface dip angles being steeper and significantly differing from predictions based on the Mohr-Coulomb criterion. In contrast, under high confining pressure, the failure mode of the rock is dominated by shear failure, and the fracture surface dip angle tends to align more closely with the predictions of the Mohr-Coulomb criterion19.

The microscopic structure of the rock plays a crucial role in controlling its macroscopic mechanical behavior under triaxial compression20. Rocks with uniform mineral composition and consistent particle size are more prone to plastic failure, whereas rocks with dispersed particle sizes exhibit significant suppression of plastic failure21. The relationship between the microscopic particle size of rocks and their macroscopic mechanical properties adheres to the Hall-Petch empirical relationship. As the average grain size of the rock increases, the critical confining pressure required for the brittle-ductile transition significantly decreases22. Large particles in the rock play a key role in resisting deformation and transmitting stress, while smaller particles are more likely to rotate under pressure, and as axial pressure increases, more small particles undergo rotation23. Under triaxial compression, two types of microcracks develop within the rock: one is intergranular cracking, which occurs primarily along grain boundaries, and the other is intragranular or transgranular cracking, which forms along the cleavage planes of the crystals24. By combining “equivalent rock mass” numerical simulations with laboratory rock mechanics tests, it is found that the mechanical response of the rock is mainly controlled by the opening of pre-existing fractures, the initiation and propagation of new cracks, and the interaction between cracks25. Considering the elastic deformation of particles, elastic-plastic deformation of contact surfaces, and the cracking mechanisms within and between particles, a numerical model can be constructed to effectively simulate the rock’s stress-strain relationship and failure characteristics. This model successfully reveals the mechanical response and failure evolution of rocks under complex stress states26.

Cundall and Strack27 proposed the particle flow method and PFC program based on the discrete element theory. This method has been applied to the study of the fundamental properties of rock-like materials, the dynamic response of granular materials, and the fracture mechanisms and crack evolution patterns of rock-like materials, yielding significant results28,29.

Previous studies have enriched our understanding of the macroscopic mechanical properties and failure mechanisms of rocks under high-stress conditions. However, since the samples are typically not taken from deep underground, their test results may lack representativeness. Furthermore, in triaxial compression tests, the failure process and internal conditions are difficult to directly observe, highlighting the need for more comprehensive analysis of deep rock samples through discrete element numerical simulation. Discrete element modeling not only reproduces the macroscopic mechanical characteristics of rocks, but also reveals the development and evolution mechanisms of internal cracks. This study integrates experimental testing with discrete element simulations, determining the macroscopic mechanical properties of the rock while also simulating the evolution process and failure modes of internal cracks. Additionally, the relationship between microfracture patterns and macroscopic mechanical behaviors is analyzed. The results provide important references for the design and safety assessment of deep underground engineering.

Engineering background

As shown in Fig. 1, the Jinping II Hydropower Station is located at the Jinping Big River Bay on the Yalong River mainstream in Sichuan Province, China. The design team has made full use of the natural elevation drop at the Jinping Big River Bay by excavating tunnels to shorten the flow path for water diversion and power generation. The water diversion system of the station consists of four pressurized tunnels, each with a diameter of 13 m. The tunnels range in length from 16 to 19 km, with an average burial depth of 1610 m and a maximum burial depth of 2525 m. Notably, 75% of the tunnel length is located at depths greater than 1500 meters30.

The locations of the Yalong River and Jinping water diversion tunnel. The map was independently created by the corresponding author using publicly available geographic information from Baidu Map V21 (https://map.baidu.com/) and drawn with Microsoft PowerPoint.

The deep surrounding rock environment of the water diversion tunnels at Jinping II exhibits significantly higher in-situ stresses compared to shallow tunnels. Measurements show that the maximum principal stress is 46 MPa and the minimum principal stress is 26 MPa, with the expected maximum stress at the deepest point of the tunnel reaching 70 MPa. The properties of geotechnical materials are key determining factors in geotechnical engineering31,32. The surrounding rock of the diversion tunnels is primarily composed of Triassic Middle and Upper Series marble, limestone, sandstone, and slate, with marble being the dominant material. Rock bursts induced by high stresses are a major engineering geological concern in this region. The marble samples used in this study were sourced from the western end of Tunnel No. 3 at the Jinping II Hydropower Station’s water diversion system, and belong to the Triassic Middle Series Zagu Nao Formation (T2Z). The marble samples used in the experiment are white or light gray in appearance, and the rock primarily consists of medium to fine-grained crystals.

Triaxial compression experiments

Rock specimens and experimental apparatus

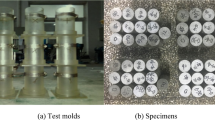

The rock specimens used in this study were sourced from deep strata at depths exceeding 1500 m. All rock samples were extracted from the same rock mass and drilled in the same direction to minimize the influence of material anisotropy and sample variability on the experimental results. The rock exhibits a medium to fine-grained texture, with a highly uniform composition and no visible inclusions or structural discontinuities. Prior to testing, all specimens were processed into Φ50 mm \(\:\times\:\) 100 mm standard cylinders, and allowed to air dry. Two ends of the specimens were perpendicular to the height, with surface roughness smaller than 0.05 mm. The five specimens subjected to confining pressures of 10 MPa, 20 MPa, 30 MPa, 35 MPa, and 40 MPa were designated as S-1, S-2, S-3, S-4, and S-5, respectively.

The experiment was accomplished on the RMT-150 rock mechanics servo-controlled testing system in the Rock Laboratory of Changjiang River Scientific Research Institute (Fig. 2). The Changjiang River Scientific Research Institute, in collaboration with the Institute of Rock and Soil Mechanics of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, upgraded and modified the existing control system. This upgrade improved the accuracy and performance of the hydraulic power system and the numerical control equipment of the testing machine. During the experiment, the axial load was stabilized and applied through the feedback signal of the sensor. The axial and hoop strains of the rock specimens were measured by using LVDT and high-precision strain gauges.

Experimental procedure

The confining pressure in this experiment was set at five levels: 10 MPa, 20 MPa, 30 MPa, 35 MPa, and 40 MPa. Prior to the experiment, shrink tubing was applied to seal the specimens, and LVDT was installed on the outer surface of the specimens. Once the specimens were properly installed, confining and axial pressures were applied simultaneously using a hydrostatic pressurization method at a loading rate of 0.05 MPa/s. The pressures were increased until the target confining pressure was reached, and then stabilized for 1 min. Following this, axial load was applied at a displacement-controlled rate of 0.002 mm/s. After the specimen reached its peak strength, the axial displacement rate was maintained to obtain the post-peak stress-strain curve. Once the specimen failed completely, the loading was stopped, and the hydraulic oil in the testing chamber was drained. The specimen was then removed, and the failure mode was observed and recorded.

Finally, small fragments were collected from the fracture surface of the specimen, prepared into suitable samples for scanning electron microscopy (SEM) observation, and sent to the SEM laboratory for detailed examination of the fracture morphology. Figure 3 shows the fracture samples coated with gold for SEM observation.

Failure modes of marble samples under different confining pressures

Figure 4 illustrates the failure modes of marble samples under different confining pressures. It can be observed that the rock samples predominantly exhibit shear failure along a macro single fracture plane. As the confining pressure increases, the angle between the main fracture plane and the direction of the maximum principal stress gradually increases. Examination of the macro fracture surfaces of the rock samples reveals that under low confining pressure, the fracture surfaces are relatively rough. However, with increasing confining pressure, the fracture surfaces become progressively smoother. Furthermore, under higher confining pressures, white rock powder is observed along the shear fracture surfaces, which is likely a result of intense frictional forces.

Result analysis

Axial stress-strain curve of deep marble under different confining pressures

Figure 5 presents the triaxial compression stress-strain curves of deep marble samples under varying confining pressures. It can be observed that, at lower confining pressures of 10 MPa and 20 MPa, the stress-strain curves exhibit a distinct peak, with the post-peak deformation capability of the rock being relatively weak. However, when the confining pressure increases to 30 MPa, the peak of the stress-strain curve becomes less pronounced, and the post-peak stage exhibits ideal plastic behavior.

Hoek33 classified rock failure modes into brittle failure, ductile failure, and a transitional state between the two. Brittle failure is characterized by a rapid reduction in the rock’s load-bearing capacity with increasing deformation, while ductile failure is marked by the rock maintaining its load-bearing ability while undergoing permanent deformation. As seen in Fig. 5, with increasing confining pressure, the failure mode of the rock gradually transitions from brittle to ductile. In this experiment, it can be inferred that at confining pressures between 20 MPa and 30 MPa, the deep marble transitions from brittle to ductile behavior.

Confining pressure effect on the peak strengths of marbles under triaxial compression

To quantify the differential effect of confining pressure on the peak strengths of the rock samples, a confining pressure effect coefficient is defined as follows:

Where K is the confining pressure effect coefficient, σ1 is the peak stress (or strength) under different confining pressures, σ3 is the confining pressure, and Rc is the uniaxial compressive strength. A higher confining pressure effect coefficient indicates a greater increase in peak strength per unit of confining pressure.

Figure 6 shows the relationship between confining pressure and the corresponding confining pressure effect coefficient, while Table 1 lists the specific values calculated based on the experimental data. As seen in Fig. 6; Table 1, the confining pressure effect coefficient decreases as confining pressure increases, and remains relatively constant once the confining pressure exceeds 30 MPa. This suggests that beyond 30 MPa, the increase in peak strength of deep marble samples slows down significantly. After the rock exhibits ductile failure characteristics, further increases in confining pressure no longer result in a significant improvement in rock strength.

Elastic modulus of deep marble under different confining pressures

Table 2 presents the elastic modulus values of marble samples under different confining pressure conditions. For each confining pressure level, the elastic modulus was measured at 25%, 45%, and 65% axial stress levels. Figure 7 illustrates the trend of the average elastic modulus values and their standard deviations under varying confining pressures.

As shown in Fig. 7, when the confining pressure is less than 30 MPa, the elastic modulus of the rock remains nearly constant or even slightly decreases as the confining pressure increases. However, when the confining pressure exceeds 30 MPa, the elastic modulus of the rock gradually increases with the rising confining pressure. This increase in elastic modulus can be attributed to the gradual reduction in the shear failure angle of the rock as the confining pressure increases, which, in turn, makes axial deformation more difficult. Consequently, when the confining pressure is greater than 30 MPa, the elastic modulus of the rock shows a steady upward trend.

As shown in Fig. 4, when the confining pressure is 30 MPa, the rock sample exhibits two branches of the main fracture. One branch has a relatively steep dip angle, which makes the sample more susceptible to axial deformation. This leads to a noticeable reduction in the elastic modulus under 30 MPa confining pressure. Overall, there is a significant correlation between the dip angle of the main fracture and the axial elastic modulus of the rock sample. The steeper the dip angle, the lower the elastic modulus. Generally, as the confining pressure increases, the dip angle of the main fracture tends to become gentler, resulting in a gradual increase in the elastic modulus.

Evolution of strength parameters of deep marble under different confining pressures

In geotechnical engineering, the linear Mohr-Coulomb (M-C) strength criterion is commonly used. In the M-C strength criterion, the relationship between the maximum and minimum principal stresses is linear. Its expression is given as:

Where σ1 and σ3 corresponding to the maximum and minimum principal stresses of the peak strengths, \({q_\text{p}}\)is the uniaxial compressive strength, and \({M_\text{p}}\) is a constant. The relationship between the maximum and minimum principal stresses and the rock’s shear strength parameters, cohesion C and internal friction angle \(\varphi\), can be expressed as:

By rearranging Eq. (2), the Mohr-Coulomb strength expression can be derived as:

Where \(\tau\) is the shear stress on the yield surface and \({\sigma _\text{n}}\) is the normal stress on the yield surface. The rock’s shear strength consists of two components: one is the cohesion on the yield surface, which resists shear, and the other is the frictional resistance, which is proportional to the normal stress \({\sigma _\text{n}}\), with a proportionality coefficient of \(\tan \varphi\).

The strength values of the marble samples S-1, S-2, and S-3 under confining pressures of 10–30 MPa are linearly fitted to obtain the cohesion C = 39.97 MPa and internal friction angle \(\varphi\)= 42.8°. Thus, the Mohr-Coulomb strength criterion for confining pressures of 10–30 MPa is expressed as:

The strength values of the marble samples S-3, S-4, and S-5 under confining pressures of 30–40 MPa are linearly fitted to obtain the cohesion C = 49.83 MPa and internal friction angle \(\varphi\)= 38.8°. Therefore, the Mohr-Coulomb strength criterion for confining pressures of 30–40 MPa is expressed as:

Figure 8 presents the M-C strength envelope fitted using the principal stress expressions. From Fig. 8, it can be observed that, in the high confining pressure range, the M-C strength envelope becomes flatter. This indicates that the internal friction angle of the rock at high confining pressures is smaller than that at low confining pressures, while the cohesion of the rock at high confining pressures is greater than that at low confining pressures.

Evolution of mechanical properties of deep marble under different confining pressures

The results of triaxial compression tests on deep marble from the Jinping region indicate that significant changes in the rock’s mechanical properties occur when the confining pressure exceeds 30 MPa. Therefore, in this study, confining pressures below 30 MPa are referred to as low confining pressure, while confining pressures of 30 MPa and above are considered high confining pressure.

Table 3 presents the evolution of the mechanical properties of deep marble under different confining pressure conditions. Under low confining pressure conditions, the stress-strain curve of the rock exhibits a relatively weak post-peak deformation capacity. As the confining pressure increases, the peak strength of the rock rises significantly, while the elastic modulus shows minimal variation. Similarly, under low confining pressures, the rock’s cohesion is relatively low, while the internal friction angle is higher.

In contrast, under high confining pressure conditions, the stress-strain curve of the rock displays ideal elastoplastic deformation characteristics. As the confining pressure increases, the increase in peak strength gradually diminishes, while the elastic modulus increases. Furthermore, under high confining pressures, the rock’s cohesion is higher, while the internal friction angle is lower.

Microscopic morphological characteristics of marble fracture surfaces under different confining pressures

Figure 9 presents scanning electron microscope (SEM) images of the fracture surfaces of the rock. It is evident from Fig. 9 that under different confining pressures, the fracture surfaces of the rock display distinct layering and cutting marks, with the fractures exhibiting a rough, irregular surface. This indicates that both low and high confining pressures lead to transgranular fractures in the rock.

Figure 9(a) shows that under low confining pressures, the layered surface of the fracture is relatively smooth, with distinct fracture edges. There are fewer transgranular fragments caused by shear friction, and the fragments are polygonal and irregular in size. The smooth fracture surface suggests that, under low confining pressure conditions, the rock primarily fractures along grain boundaries, with transgranular fractures occurring as secondary. No clear friction marks are observed on the transgranular fracture surfaces, indicating that the transgranular fractures primarily occur in a tensile mode.

Figure 9(b) shows that under high confining pressure, the layered surface of the fracture is blurred, with the edges being smoothed. There are more transgranular fragments produced by shear friction, and these fragments are spherical and accumulate on the fracture surface. These microscopic characteristics suggest that, under high confining pressure conditions, the rock primarily undergoes transgranular failure, and friction marks are evident after the grains are sheared through, indicating a failure mode dominated by shear friction after transgranular fracture.

Overall, the microscopic characteristics of the marble fracture surfaces suggest that, under high confining pressure, the rock exhibits higher wear at the fracture surface after transgranular failure, with the dominant failure mechanism being shear friction following transgranular fracture. In contrast, under low confining pressure, while transgranular failure also occurs, there is no significant wear at the fracture surface, and the fracture is mainly dominated by tensile failure. Under low confining pressure, the rock primarily fractures along grain boundaries, where the shear strength of the grain boundaries controls the strength of the fracture surface. After local transgranular failure occurs, the rock’s load-bearing capacity decreases sharply, leading to low wear after transgranular failure. Under high confining pressure, the rock predominantly experiences transgranular failure, with the shear strength of the grains controlling the strength of the fracture surface, leading to higher wear at the fracture surface.

Numerical simulation of fracture mechanisms in triaxial compression of deep marble

Discrete element model construction

Rock samples contain a large number of grain boundaries, whose mechanical properties are typically weaker than those of the rock’s crystal material. Due to the random distribution of grain boundaries, the rock samples exhibit heterogeneity and anisotropy. Under different confining pressure conditions, grain boundaries serve as a medium for transferring the load-bearing structure of the rock, significantly influencing the variation of its mechanical properties.

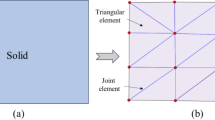

As shown in Fig. 10, the particle model has dimensions of 100 mm × 50 mm and is constructed from a series of circular particles (see Fig. 10). The steps for generating the equivalent crystalline model of marble are as follows: (1) create initial circular particles that match the size of mineral crystals. (2) perform Voronoi tessellation on the circular particles, remove the original particles, and consider the boundaries of the tessellated regions as the boundaries of the mineral crystals. (3) fill each mineral crystal region with smaller circular particles, ensuring that each particle has at least three contact points.

As shown in Fig. 11, two types of contact models are set within the GBM model: the contact between particles within the grains is defined as a parallel bond model, while the contact at the crystalline network surfaces is defined as a smooth-joint model. The micro-mechanical parameters of the model are summarized in Table 4.

The micro-mechanical parameter calibration process was as follows: (1) Fundamental mechanical tests were conducted to determine the macroscopic mechanical properties of the actual rock material, including elastic modulus, tensile strength, uniaxial compressive strength, and compressive strength under various confining pressures. (2) The geometric distribution of grains was determined, and the mechanical properties within and between grains were estimated based on relevant literature and engineering experience. (3) Numerical simulations were then carried out, and mesoscopic parameters were iteratively adjusted to match the laboratory results.

The advantages of applying the smooth-joint (S-J) model at grain boundaries are as follows: (1) The use of the S-J model at grain boundaries enables more accurate simulation of joint or boundary behavior in crystalline rocks. Unlike conventional contact models, it is independent of particle contact orientation. Instead, contact behavior aligns with the predefined joint plane, allowing particles to overlap and slide upon failure. This effectively prevents artificial crack bypassing and local geometric dilation34. (2) In traditional bonded-particle models, the uniaxial compressive strength (UCS)/tensile strength (TS) ratio is often overestimated compared to laboratory results. By combining particle bonds within grains and the S-J model at grain boundaries, the simulated UCS/TS ratio aligns more closely with experimental data, better capturing the actual mechanical behavior of rocks35. (3) The S-J model provides a more realistic representation of rock failure by reproducing the weak interface behavior between grains, including sliding, separation, and shear failure. This allows clear distinction between intergranular and intragranular failure, enhancing the accuracy of fracture initiation and propagation simulations.

Figure 12 shows the stress conditions of the model. Confining pressure is applied first, followed by axial pressure until the model fails.

Modeling results

(1) Complete stress–strain curves of the marble numerical model.

Figure 13 shows the axial stress-strain curves of the numerical model under different confining pressure conditions. As observed in the Fig. 13, when the confining pressure exceeds 30 MPa, the rate of increase in peak stress significantly slows down, which is consistent with the results from actual experiments. Due to the limitations in the number of particles in the numerical model, it is difficult to simulate the ideal plastic deformation characteristics observed at high confining pressures.

Figure 14 illustrates the crack distribution of the marble numerical model under different confining pressure conditions. In the Fig. 14, red cracks represent grain boundary fractures, while black cracks indicate fractures within the grains. Grain boundary cracks reflect the cracking process along the boundaries of the rock grains, while internal grain cracks represent the rupture of the rock grain.

As shown in Fig. 14, under triaxial compression, the macroscopic shear failure surface of the rock is predominantly controlled by the propagation of black cracks. Under low confining pressure conditions (< 30 MPa), there are fewer internal grain fractures, leading to insufficient fracture development and less distinct primary failure surfaces. In contrast, under high confining pressure conditions (> 30 MPa), internal grain fractures are more developed, the fracture surfaces are more concentrated, and the primary failure surface is more easily identifiable.

(2) Statistical Analysis of Crack Propagation in the Numerical Model.

Figure 15 presents the statistical distribution of the number of cracks in the marble model after failure under triaxial compression. As shown in Fig. 15, with increasing confining pressure, the number of cracks along the grain boundaries decreases, while the number of fractures within the grains significantly increases. When the confining pressure exceeds 30 MPa, the rate of increase in the number of internal grain fractures slows down, and the total number of cracks tends to stabilize.

Figure 16 illustrates the proportion of transgranular cracks to grain boundary cracks under different confining pressure conditions. As shown in Fig. 16, with the increase in confining pressure, the crack propagation mode of the rock gradually shifts from being dominated by grain boundary fractures to being primarily controlled by transgranular fractures. When the confining pressure reaches a critical value (30 MPa in this study), the rate of increase in the number of internal grain fractures begins to slow down. Compared to grain boundary fractures, transgranular fractures exhibit higher cohesion. After internal grain fractures, the particles are sheared and ground into smaller sizes, resulting in a lower internal friction angle.

Micromechanisms of marble’s macroscopic mechanical property evolution under triaxial compression

As the confining pressure gradually increases, the grain boundaries within the rock sample are compacted, and its internal structure becomes denser, which is reflected in the gradual increase in the cohesion (C) of the rock. At the same time, the increase in confining pressure promotes the interlocking of grain boundaries, leading to further development of transgranular cracks and a reduction in the size of particles produced during failure. This results in a decrease in the internal friction angle of the rock after failure.

Under conventional triaxial compression conditions, when the confining pressure is below 30 MPa, fractures primarily occur along grain boundaries, leading to lower peak strength. As the confining pressure increases from low to high, the grain boundaries are progressively compacted and interlocked, causing a shift in the failure mode toward predominately transgranular fracturing. The interlocking effect of the grain boundaries significantly increases the peak strength of the rock during this stage. When the confining pressure reaches 30 MPa, the grain boundaries become fully interlocked, and the rock essentially transitions to a transgranular failure mode. At this point, the interlocking effect of the grain boundaries under confining pressure is no longer significant, and the growth of peak strength plateaus.

Conclusions and discussion

This study investigates the evolution of mechanical properties of deep marble samples from the Jinping region, with depths exceeding 1500 m, through triaxial compression tests, rock fracture morphology scanning, and discrete element numerical simulations. The results systematically explore the mechanical property evolution of deep marble under triaxial compression. The findings indicate that the differences in the micromechanical fracture mechanisms under varying confining pressures are key factors in the macroscopic mechanical property changes.

The triaxial test results for deep marble from Jinping indicate that when the confining pressure exceeds 30 MPa, the mechanical properties of the rock undergo significant changes. Under low confining pressures, the stress-strain curve of the rock exhibits relatively weak post-peak deformation behavior. As confining pressure increases, the peak strength of the rock rises significantly, but the elastic modulus shows no noticeable change. Under these conditions, the rock has low cohesion and a high internal friction angle. Conversely, under high confining pressure conditions, the stress-strain curve demonstrates more ideal plastic deformation characteristics. As confining pressure increases, the rate of increase in peak strength gradually diminishes, while the elastic modulus increases. Under high confining pressure, the rock exhibits higher cohesion and a lower internal friction angle.

Microscopic features of the marble fractures indicate that, under low confining pressure, there is little wear on the fracture surface, and the fracture fragments are fewer and polygonal. The failure mechanism is mainly dominated by tensile fracture along grain boundaries. Under high confining pressures, however, the degree of wear on the fracture surface is higher, with more fragment debris that is spherical in shape. The failure mechanism is primarily shear friction following transgranular fracture.

With increasing confining pressure, the shear angle of the rock fracture decreases, making axial deformation of the rock more difficult. This results in a gradual increase in the elastic modulus of the rock when the confining pressure exceeds 30 MPa. Under low confining pressure conditions, the interlocking effect of grain boundaries is weak, and failure primarily occurs along grain boundaries. Due to the weak bonding between the boundaries, cohesion is low. Additionally, the fracture surfaces formed along the grain boundaries are rough, leading to a higher internal friction angle. Under high confining pressure, the interlocking effect of grain boundaries becomes stronger, and failure primarily occurs within the grains. The higher strength of the grains results in increased cohesion, while the fracture surfaces formed along the grains are smoother, leading to a lower internal friction angle.

The confining pressure at which the grain boundaries are fully interlocked represents the brittle-ductile transition pressure. In underground engineering stability analysis, when applying the M-C failure criterion, the strength envelope should be divided into at least two segments, with the transition point between the two segments representing the brittle-ductile transition stress.

To address current limitations and guide future work, we plan to incorporate triaxial unloading tests and corresponding PFC simulations under high confining pressure conditions to better replicate the stress paths encountered by surrounding rock in engineering environments. Moreover, to enhance applicability at the engineering scale, future research will focus on jointed rock masses. This includes field monitoring and discrete element modeling of failure mechanisms in jointed rock masses, aiming to provide more practical insights for rock mechanics researchers and mining engineers.

Data availability

Data sets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Kumar, K. R., Honorio, H. T. & Hajibeygi, H. Simulation of the inelastic deformation of porous reservoirs under Cyclic loading relevant for underground hydrogen storage. Sci. Rep. 12, 21404. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-25715-z (2022).

Chang, J., Qi, Y., Yang, R. & Hao, T. The self-healing property of rock salt damage in underground gas storage: A review. Results Eng. 27, 106098. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2025.106098 (2025).

Yang, S., Su, C. & Xu, W. Experimental investigation on strength and deformation properties of marble under conventional triaxial compression. Rock. Soil. Mech. 26, 475–478 (2000).

Tan, Y. et al. Study on the disaster caused by the linkage failure of the residual coal pillar and rock stratum during multiple coal seam mining: mechanism of progressive and dynamic failure. Int J. Coal Sci. Technol. 10, 45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40789-023-00603-7 (2023).

Zhao, Q. et al. Acoustic emission and failure characteristics of coal and rock under single-free-face true triaxial loading. Eng. Fail. Anal. 161, 108299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2024.108299 (2024).

Zhang, W. et al. In-situ and experimental investigations of the failure characteristics of surrounding rock through granites with biotite interlayers in a tunnel. Eng. Geol. 343, 107816. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2024.107816 (2024).

Butt, A., Hedayat, A. & Moradian, O. Microseismic monitoring of laboratory hydraulic fracturing experiments in granitic rocks for different fracture propagation regimes. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 57, 2035–2059. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-023-03669-6 (2024).

Lagioia, R. & Nova, R. An experimental and theoretical study of the behaviour of a calcarenite in triaxial compression. Géotechnique 45, 633–648. https://doi.org/10.1680/geot.1995.45.4.633 (1995).

Yang, S., Jing, H. & Wang, S. Experimental investigation on the strength, deformability, failure behavior and acoustic emission locations of red sandstone under triaxial compression. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 45, 583–606. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-011-0208-8 (2012).

Wang, D. et al. Quantitative analysis of fracture dynamic evolution in coal subjected to uniaxial and triaxial compression loads based on industrial CT and fractal theory. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 196, 108051. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2020.108051 (2021).

Zong, Y., Han, L., Wei, J. & Wen, S. Mechanical and damage evolution properties of sandstone under triaxial compression. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 26, 601–607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmst.2016.05.011 (2016).

Zhang, J., Lin, Z., Dong, B. & Guo, R. Triaxial compression testing at constant and reducing confining pressure for the mechanical characterization of a specific type of sandstone. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 54, 1999–2012. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-020-02357-z (2021).

Li, J. et al. On the mechanical properties and failure mechanism of conglomerate specimens subjected to triaxial compression tests. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 56, 973–995. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-022-03110-4 (2023).

Duan, K. et al. Micro-mechanical analysis of the failure process of conglomerate: insights from DEM simulation with physics-based gravel structure. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-025-04609-2 (2025).

Zhao, J. et al. Large deformation characteristics and mechanisms of deep-buried foliated basalt tunnel: A case study of the Haba snow mountain tunnel. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 58, 3523–3544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-024-04301-x (2025).

Ghazvinian, A. H., Fathi, A. & Moradian, Z. A. Failure behavior of Marlstone under triaxial compression. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. 45, 807–814. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2007.09.006 (2008).

Zhou, S. et al. Evaluating nonlinear plastic dilatation behaviors of sandstone using stress-dilatancy models. Int. J. Civ. Eng. 22, 2167–2191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40999-024-01008-6 (2024).

Ramamurthy, T. Shear strength response of some geological materials in triaxial compression. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. 38, 683–697. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1365-1609(01)00035-1 (2001). https://doi.org/https://

Jiang, Q., Zhong, S., Cui, J., Feng, X. & Song, L. Statistical characterization of the mechanical parameters of intact rock under triaxial compression: an experimental proof of the Jinping marble. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 49, 4631–4646. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-016-1054-5 (2016).

Cao, F. et al. Quantitative characterization of the multiscale mechanical properties of low-permeability sandstone roofs of coal seams based on nanoindentation and triaxial tests and its implications for CO2 geological sequestration. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 12, 5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40789-024-00739-0 (2025).

Klein, E., Baud, P., Reuschlé, T. & Wong, T. f. Mechanical behaviour and failure mode of Bentheim sandstone under triaxial compression. Phys. Chem. Earth Pt A-Solid Earth Geod. 26, 21–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1464-1895(01)00017-5 (2001).

Liu, S. L. et al. Constitutive modeling of rock failure behavior under pressure conditions spanning the brittle-ductile transition. Int. J. Non-Linear Mech. 175, 105117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnonlinmec.2025.105117 (2025).

Huang, Y. et al. Numerical simulation study on macroscopic mechanical behaviors and micro-motion characteristics of gangues under triaxial compression. Powder Technol. 320, 668–684. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2017.08.002 (2017).

Manthei, G. Characterization of acoustic emission sources in a rock salt specimen under triaxial compression. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Amer. 95, 1674–1700. https://doi.org/10.1785/0120040076 (2005).

Zhou, Y., Wu, S., Gao, Y. & Misra, A. Macro and meso analysis of jointed rock mass triaxial compression test by using equivalent rock mass (ERM) technique. J. Cent. South. Univ. 21, 1125–1135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11771-014-2045-x (2014).

Chen, W. & Konietzky, H. Simulation of heterogeneity, creep, damage and lifetime for loaded brittle rocks. Tectonophysics 633, 164–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tecto.2014.06.033 (2014).

Cundall, P. A. & Strack, O. D. L. A discrete numerical model for granular assemblies. Géotechnique 29, 47–65. https://doi.org/10.1680/geot.1979.29.1.47 (1979).

Peng, J., Wong, L. N. Y. & Teh, C. I. Effects of grain size-to-particle size ratio on micro-cracking behavior using a bonded-particle grain-based model. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. 100, 207–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2017.10.004 (2017).

Zhang, H. et al. Fracture behavior of rock with initial damage: theoretical, experimental, and numerical investigations. Geofluids 8886843. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8886843 (2020).

Wang, B., Zhu, J. & Wu, A. Experiment study on mechanical properties of Jinping marble under loading and unloading stress paths. Chin. J. Rock. Mech. Eng. 27, 2138–2145 (2008).

Wu, D. et al. Ground deformation characteristics induced by mechanized shield twin tunnelling along curved alignments. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2021 (6640072). https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6640072 (2021).

Guo, P. et al. Soil Creep Effect on Time-Dependent Deformation of Deep Braced Excavation. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 5655592. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/5655592 (2022).

Hoek, E. & Brown, E. T. Underground Excavations in Rock (CRC, 1980).

Hu, X. et al. Influence of meso-structure heterogeneity on granite strength and deformation with particle flow code. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 42, 1540–1548. https://doi.org/10.11779/CJGE202008020 (2020).

Wong, L. N. Y., Peng, J. & Teh, C. I. Numerical investigation of mineralogical composition effect on strength and micro-cracking behavior of crystalline rocks. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 53, 191–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jngse.2018.03.004 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors greatly acknowledge the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2023YFC2907201).

Funding

This work was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2023YFC2907201).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zanmin Xiong: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Writing - Original Draft; Dongsheng Chen: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Methodology, Formal Analysis; Bei Jia: Conceptualization, Funding Acquisition, Resources, Writing - Review & Editing; Xiaobo Su: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Resources, Supervision, Writing - Review & Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiong, Z., Chen, D., Jia, B. et al. Experimental and numerical investigation on mechanical properties and fracture mechanisms of deep marble under triaxial compression. Sci Rep 15, 28496 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14356-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14356-7