Abstract

Software Effort estimation (SEE) is a vital task for project management as it is essential for resource allocation and project planning. Numerous algorithms have been investigated for forecasting software effort, yet achieving precise predictions remains a significant hurdle in the software industry. To achieve optimal accuracy, machine learning algorithms are employed. Remarkably, Random Forest (RF) algorithm produced better accuracy when compared with various algorithms. In this paper, the prediction is extended by increasing the number of trees and Improved Random Forest (IRF) is implemented by including three decision techniques such as residual analysis, partial dependence plots and feature engineering to improve prediction accuracy. To make improved random forest to be adaptive, it is further extended in this paper by integrating three techniques such as: Bayesian Optimization with Deep Kernel Learning (BO-DKL) to adaptively set hyperparameters, Time-Series Residual Analysis to detect autocorrelation patterns among model error, and Explainable AI techniques Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) and Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations (LIME) to improve feature interpretability. This Improved Adaptive Random Forest (IARF) mutually contributes to a comprehensive evaluation and improvement of accuracy in prediction. Metrics used for evaluation are Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), R-Squared, Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE), Mean Absolute Scaled Error (MASE) and Prediction Interval Coverage Probability (PICP). Overall, the improved adaptive RF model had an average improvement ratio of 18.5% on MAE, 20.3% on RMSE, 3.8% on R2, 5.4% on MAPE, 7% reduction in MASE and a 3–5% improvement in PICP across all data sets compared to the Random Forest model, with much improved prediction accuracy. These findings validate that the combination of adaptive learning methods and explainability-based adjustments considerably improves accuracy of software effort estimation models and facilitates more trustworthy decision-making in software development projects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Initial stages of software development, incurs more uncertainty, complexities and requires reliable and accurate effort estimations. Software effort estimation is a challenging aspect of project management, and its decisions are related to allocation of resources, project plan and helps in overall success of the project. The fundamental aspect for a software project is to accurately predict the software effort, which in turn ensures on time delivery of project, budget and quality. In this paper, diverse methods and algorithms are employed to increase the efficiency and accuracy of the software effort estimation.

Precise software effort estimation is vital for effective project management. It assists the stakeholders to know about the resources required to complete the project and helps in allocation of financial and human resources. Additionally, it helps establish accurate project timelines and milestones, facilitating better planning and team management. Overall project success can be affected by inaccurate project estimates, which also lead to overproduction of budget, project delays, and underutilization of resources.

Various techniques are used to estimate software effort; By examining data from past projects, these algorithms predict the amount of work needed for future initiatives. Key algorithms include k-nearest neighbors, LightGBM, XGBoost, recurrent neural networks, support vector machines, decision trees, random forests, and linear regression. This paper presents a two-fold contribution to advance the state of software effort estimation.

Firstly, an Improved Random Forest model1 is constructed by integrating three decision strategies—residual analysis, partial dependence plots, and feature engineering—to improve prediction. Secondly, this model is extended to an Improved Adaptive Random Forest by further adding Bayesian Optimization with Deep Kernel Learning (BO-DKL), Time-Series Residual Analysis, and Explainable AI methodologies like SHAP and LIME to further enhance adaptability and interpretability.

Residual analysis2 supports software effort estimation by finding differences between predicted and actual levels of effort. By examining those residuals, particularly in a time-series environment, the model is able to account for systematic biases as well as autocorrelation patterns, which can be efficiently corrected. This results in better and more accurate predictions, especially for projects with different complexities and scales. Partial dependence plots (PDPs) also help to visualize the marginal contribution of one feature to the predicted effort with other features held constant. The method reveals non-linear interactions and relationships among features, which are normally ignored by standard models. By incorporating PDPs, the model develops a greater knowledgeable understanding of how specific project features affect effort in order to estimate smarter and more accurate predictions.

Feature engineering augments the model by constructing new information-rich features from the base features3. For example, joining lines of code with cyclomatic complexity can identify modules with elevated complexity per line of code, which are high-effort predictors. This enrichment of the dataset makes the model better able to catch omissive patterns and generalize across types of projects.

On top of such advancements, adaptive Random Forest brings forth BO-DKL as a novel technique for dynamically optimizing hyperparameters like the number of trees, tree depth, and feature splits. As opposed to the conventional grid search procedures, BO-DKL employs probabilistic modeling to help navigate the hyperparameter space effectively and optimize model performance without restraint in computation overhead. Such an adaptability is especially required for use with heterogeneous datasets and changing project demands. Time-Series Residual Analysis is a supplement to common residual checks that examines the pattern over time of prediction errors. The method detects trends and autocorrelations in residuals, which are prevalent in actual software projects if effort behavior changes over time. With this analysis included, the model is more sensitive to dynamics over time and hence more predictive reliable.

Explainable AI methods, LIME and SHAP4, are utilized together to increase model transparency. Global interpretability is offered by SHAP by providing each feature’s contribution to the model’s predictions so that the stakeholders know the general principle of decision-making. LIME further takes it one step ahead by providing local interpretability in that it provides explanations of individual predictions and how specific estimates differ from the mean. The two tools jointly increase the transparency and dependability of the model’s decisions to support improved stakeholder communication and decision-making.

While machine learning has been applied extensively in SEE, there are some limitations that persist. Models of many tasks are non-adaptive to project changing conditions, statically assume scope, and do not cope with temporal trends. Very accurate models are black boxes, with little explanatory power in terms of feature contribution. Few models handle with uncertainty in predictions, and few explore complex feature interactions. Residual diagnostics are underutilized, and integration into project management practice is minimal.

This research fills these gaps using the contribution of adaptive decision strategies correcting model predictions upon residual trends and feature interactions, dynamic hyperparameter tuning with BO-DKL, and combining SHAP and LIME for enhanced explainability. An extensive experiment on five benchmark datasets with varied metrics (MAE, RMSE, R², MAPE, MASE, and PICP) guarantees high performance and generalizability. This two-phase enrichment initially through decision methods and subsequently explainability and adaptive learning puts the suggested model at a frontier of innovation in software effort estimation research.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section “Literature survey” offers a critical literature review, with specific emphasis on methodologies and research gaps currently existing in software effort estimation. Section Dataset description & methodology reports the datasets employed and a summary of the methodology adopted and the applied pre-processing techniques and model construction approaches. Section “Random forest” describes the Improved Adaptive Random Forest model proposed, with emphasis on the incorporation of decision procedures and adaptive learning approaches. Section “Results and discussions” reports the experimental result and comparison on a range of benchmarking data with different evaluation metrics. Section “Conclusion” concludes the paper with major findings, implications, and future work directions.

Literature survey

Effort estimation of software has been a dominant research problem in software engineering for many decades. Several artificial intelligence and machine learning methods have been employed earlier to attempt enhancing the accuracy, reliability, and use-friendliness of effort estimation models for software. This overview introduces the current established and recent algorithms with their prominent strengths and weaknesses for software effort estimation. One supervised machine learning method is linear regression5, which evaluates the strength of a linear association using a dependent variable and a set of independent features. Decision trees are a valuable tool6 in building training models to derive basic decision rules from training data to predict the class or value of a target variable. On the basis of the decision tree, the process of predicting the class label of the record begins7. We compare the values of the record attribute with the value of the original attribute. Based on this value, a comparison will indicate which branch to take to get to the next node.

The Random Forest classifier uses the average prediction from multiple decision trees trained on distinct subsets of the data set to improve the prediction accuracy of the data set. This method8 predicts the final outcome using majority voting, eliminating the need to rely on a single decision tree. Random forests in particular are increasingly popular in SEE research9. Powerful and capable of handling high-dimensional data, Random Forest has been used successfully in many different software project scenarios10. Support vector machines (SVM) are capable of solving difficult problems of regression, classification, and outlier detection by optimizing data transformations that create boundaries between data points based on predefined classes, labels or outputs through the use of supervised learning algorithms11.

Regularisation with L1/L2 penalties on tree weights and biases in XGBoost controls overfitting. Many gradient boosting solutions lack this functionality. The weighted quantile sketch approach lets XGBoost handle sparse data12. Scaling up on multicore or cluster machines is trivial. It also employs cache awareness to reduce memory utilisation when training huge dataset models. RNNs with attention mechanisms belong to the realm of deep learning models capable of capturing sequential dependencies in data. An attention mechanism enables the RNN13 examine all input elements at each time step, unlike most RNNs. Recent years have seen a surge in the exploration of deep learning approaches for SEE. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) with Attention Mechanism14, have demonstrated capabilities in capturing temporal dependencies and improving accuracy in SEE tasks. KNN is a simple algorithm that learns an unknown function with specified precision and accuracy using a local minimum of the desired function. KNN works for classification and regression15.

LightGBM is a gradient-boosting decision tree framework that improves model efficiency and memory utilisation. Data is bucketed into bins using a distribution histogram in LightGBM16. XGBoost and LightGBM continue to be key players in SEE algorithms17 and 18. These gradient boosting frameworks have proven effective in handling structured/tabular data and are recognized for their efficiency in large-scale datasets. On considering the above algorithms for prediction, Random Forest algorithm produced promising results. Furthermore, by increasing the number of trees to 500, the results are evaluated. By increasing the n umber of trees, robustness of the model increases. Feature importance, is a key aspect in Random Forest models, it analyses the contribution of ach feature for model performance. Feature importance is important and calculated using information gain of each feature during the construction of decision tree in the ensemble. It is essential to find the most influential feature of the dataset for effort prediction.

In the current research landscape on software effort estimation, certain gaps have been identified. First, there’s a limited exploration of hybrid models that bring together different algorithms for a more comprehensive estimation approach. Additionally, the impact of emerging technologies on effort estimation is not thoroughly examined, missing insights into adapting to evolving programming paradigms and advanced machine learning. The impact of non-functional requirements on estimation accuracy has not been fully explored, which hinders a comprehensive understanding of their influence on software effort estimation. Finally, the literature does not delve deeper into adaptive decision techniques for screening, an essential aspect for improving the accuracy of effort prediction. The lack of exploration of innovative adaptive decision methods adds another dimension to the current research gap, highlighting the need for in-depth research to refine software effort estimation models. Addressing these research gaps could significantly advance the practice of software effort estimation, providing more accurate and adaptable models for effective project management in the software industry.

Adaptive decision techniques for refinement

Adaptive decision methods allow us to raise the bar for effort forecast. Three techniques are employed: residual analysis, partial dependence graphs, and feature engineering. Understanding the residuals—the discrepancy between the actual and anticipated values—can help one understand how well the model works. Feature engineering enables previously unattainable data inclusion into the model by adding additional features. These adaptive decision techniques can help to further assess and enhance software effort estimating models. Understanding feature contributions is crucial for bettering model interpretation and refinement, as recent work19 highlights.

Techniques for making adaptive decisions have developed well beyond conventional ones. Time series-based residuals and autocorrelation analysis are combined in advanced residual analysis to give a more comprehensive picture of model performance. Moreover, SEE models become more transparent when SHApley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) data are included into the model description. Refinement of SEE models still starts with feature engineering. promote the combination of automated techniques with domain-specific expertise to guarantee ongoing enhancement of SEE model capability. Use of publicly available datasets to guarantee reproducibility and comparability of results has been a hallmark of research over the last ten years. Benchmark SEE methods still heavily depend on datasets like COCOMO81 and JM120.

One increasing tendency is to enhance the practical usability of SEE models by using datasets tailored to a certain sector21. Industrial data sets shed light on the difficulties presented by parameters of actual projects. These methods were assessed using Albrecht, China, Desharnais, COCOMO81, and JM1 datasets. The range of data sets enables the testing of algorithms in many situations, each with unique issues and features22.

Among the recent developments in software effort estimation, some new models have been suggested. Chen et al.23 introduced a feature selection scheme based on reinforcement learning to support estimation through dynamic feature identification in light of project management. Tran et al.24 conducted a thorough comparison of AI-based estimation models and introduced a framework integrating the best of various machine learning models for the purpose of enhancing prediction capability. Chawla and Pareek25 presented a particle swarm optimization-artificial neural network combination model that offers better prediction accuracy for some benchmark data sets. Lavingia et al.26 have also conducted a comparison of various machine learning algorithms and concluded that Random Forest Regression is a high-performance methodology for software effort estimation time and again.

Recent studies in software effort estimation have used deep learning-based methods like recurrent neural networks (RNN), convolutional neural networks (CNN), and LSTM models to manage non-linear high-dimensional project data. For instance, Sharma et al.27 presented a deep learning-based effort estimation model using LSTM networks and reported satisfactory performance for large-scale software project datasets. Also, Li et al.28 utilized an ensemble hybrid model comprising both CNN and LSTM and proved it to identify intricate dependencies in software metric data. In, Singh et al.29 RNN model performed well on large datasets such as JM1, it always performed sub-optimally for small datasets for overfitting and poor data representation.

For effort estimating, a thorough strategy to increasing forecast accuracy is provided by investigating various algorithms, evaluation measures, and adaptive decision-making techniques. This work investigates several models and analyses feature importance to show the utility of the Random Forest method. Better and more controllable software development projects can result from the enhancement and accuracy of software effort estimating models through the application of adaptive decision techniques. This work makes the following contributions: investigation and assessment of several algorithms, adaptive decision methods, evaluation metrics to fully enhance forecast accuracy in software effort estimation and detailed examination and justification of the Random Forest method, highlighting the importance of characteristics and examining several models.

Dataset description & methodology

Dataset description

Five publicly accessible benchmark data sets were used in this research to assess the performance of different machine learning algorithms in effort estimation of software. The data sets, which were downloaded from the PROMISE Repository and open sources, have projects with different attributes and complexities and hence provide a complete test environment. The data sets are briefly described in the below Table 1:

Data Pre-processing and handling missing values

Datasets that came before model training went through a uniform pre-processing pipeline to ensure homogeneity and enhanced model performance. The following were the steps employed. In data sets with missing or incomplete data (e.g., COCOMO81 and Desharnais), numerical missing values were imputed with the median of the respective feature in an attempt to reduce the impact of outliers, while categorical missing entries were imputed with the mode value.

Normalization, outlier detection and feature selection

In order to facilitate uniform feature scaling, especially for feature-range-sensitive algorithms like SVM, KNN, RNN, all numeric features were scaled to the [0,1] range through min-max normalization. Random Forest and XGBoost models did not require scaling because they are scale invariant. Categorical features like ‘Development Mode’ (in COCOMO81) and ‘Language Type’ (in China dataset) were encoded through one-hot encoding in order to facilitate the integration of such data with machine learning models with ease. An early residual check picked up extreme outliers, retained in tree-based models for their stability but exposed during learning in neural networks and regression-based models for possible trimming or winsorization. Features with low variance or multicollinear features (using 0.85 as a threshold in correlation) were excluded at the cross-validation tuning phase to ensure maximum model stability and interpretability.

Model validation and evaluation plan

To ensure the robustness and generalizability of model performance, a two-step validation strategy was used, First, for each dataset, they were divided into 70% training and 30% test, a standard split ratio used in SEE research. During model building, the training data for each model were subjected to a 5-fold cross-validation procedure in order to avoid overfitting and to allow for variance in the data. During this process, the training data were divided into five equal-sized subsets and four of the folds were utilized for training and a single fold was utilized for validation for each iteration. This process was run five times with the validation fold rotated every cycle. Cross-validation performance was averaged for model selection and hyperparameter tuning. After setting the model parameters, its performance on the unseen hold-out test data was confirmed against performance measures such as Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), R-squared (R²), and Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE).

Methodology

Effort prediction for software project must ensure timely delivery of software, budget and fulfilment of project quality standards. This critical requirement had led to the development of various algorithms that aims in improving the efficiency and precision of effort estimation of the software. Among the several algorithms, Linear Regression, Decision Tree, Random Forest, Support Vector Machine, XGBoost, Recurrent Neural Networks, k-Nearest Neighbors, and LightGBM are considered for prediction as each of the algorithm having its unique strength for prediction. Random Forest algorithm produced the best results in terms of MAE and RMSE. As an extension, Random Forest tuning and adaptive decision strategies provided higher prediction rather than random forest. Figure 1 provides the block diagram for proposed methodology.

Random forest

During training, random forests (RF) generate a large number of individual decision trees. In order to arrive at the final prediction, the mean prediction for regression or the mode of the classes for classification is computed by aggregating the predictions from all trees. They are termed ensemble techniques because they reach a conclusion based on a compilation of results.

The pseudocode for the software effort estimation process using Random Forest is provided below:

Random forest hyperparameter tuning

Apart from enlarging the trees within the Random Forest model, some critical hyperparameters Table 2, were adjusted to achieve the best model performance while minimizing overfitting. The following hyperparameters were tested:

-

Number of Trees (n_estimators): 100 through to 1000 in step sizes of 100. Best performance at 500 trees, a balance between accuracy and computational cost.

-

Maximum Depth of Trees (max_depth): 5–30 were tried. More deeply learning trees capture more complex patterns but might overfit. The best value varied slightly from dataset to dataset but across them all was 12–20.

-

Minimum Samples per Split (min_samples_split): Values from 2 to 10 were tested in order to regulate the minimum number of samples which should be used to split an internal node. A value of 4 was previously used to provide an adequate balance between model flexibility and generalization.

-

Maximum Features (max_features): Controlled the number of features that were examined when determining the optimal split. ‘auto’, ‘sqrt’, and ‘log2’ were the options compared. ‘sqrt’ was discovered to be best on average in the majority of datasets.

-

Bootstrap Sampling (bootstrap): Both True and False were tried, where True (default) always performed better by encouraging tree diversity.

-

A grid search method with 5-fold cross-validation was used to optimize systematically various sets of these hyperparameters. The optimal setting for each dataset resulted in significant improvements in predictive accuracy, particularly in terms of reductions of 3–7% in values of MAE and RMSE over default parameter settings.

Beyond the utilization of common grid search techniques, the current work employs Bayesian Optimization with Deep Kernel Learning (BO-DKL) for hyperparameter selection. BO-DKL makes dynamic hyperparameter choices based on predictive uncertainty, enhancing generalizability and computation overhead reduction.

Adaptive decision techniques for refinement In the pursuit of refining software effort estimation models, three key adaptive decision techniques are recommended.

Residual analysis (Enhanced with Time-Series Residuals) The residual denotes the discrepancy between the predicted value (ϳ) and the observed value (y) of the dependent variable. There is one residual per data point. By calculating residuals, one can determine the degree to which the regression line suits the data. Greater residuals suggest that the regression line fails to adequately represent the data, as the true data points do not approach the regression line. As the residuals decrease, it signifies that the regression line more closely approximates the data, as the actual data points approach the regression line. Time-Series Residual Analysis was incorporated within Improved RF in order to aid in the identification of trends in effort estimation. BO-DKL automatically optimizes hyperparameters, keeping error adaptation dynamic to varying project sizes.

Pseudocode

Residual plots were used to compare observed effort and forecast effort values, to find patterns of model error. For example, on the China data set, residual plots indicated that forecasts of effort for very large projects (larger than the data set’s 75th percentile) always had larger prediction errors. It was possible to recognize this trend and fine-tune the model by, for example, doubling the trees and feature split optimization, which decreased the MAE from 385 to 365 and RMSE from 1288 to 1197.

Likewise, in Albrecht dataset, residual analysis revealed outliers that possessed unusually high effort values relative to comparable projects based on function points and team experience. Pinpointing and resolving these outliers during model training brought down the MAE to 8.96 from 9.16.

Partial dependence plots (Enhanced with SHAP & LIME) A useful instrument for visualising the relationship between a target response and a set of input features of interest in a regression model are partial dependence plots (PDP). PDPs marginalise over the values of all other input features (the ‘complement’ features) to illustrate the dependence of the target response on a subset of the input features of interest. PDPs can be employed within a regression model to illustrate the correlation between a predictor and the anticipated response. By marginalising the impact of the remaining predictors, the averaged prediction is utilised to define the partial dependence on the selected predictor. SHAP-based partial dependence plots were introduced to maximize feature transparency in effort estimation, where non-linear dependencies are shown explicitly. LIME improves the local interpretability further by offering explanation for individual predictions, allowing one to be able to understand why specific effort estimates vary from overall trends encapsulated by SHAP.

Pseudocode

PDPs facilitated observation of the effect of key features on effort prediction while keeping other features at fixed levels. PDPs on COCOMO81 dataset established a non-linear relationship between the “Lines of Code” feature and effort predicted whereby effort growth was experiencing diminishing returns upon exceeding some level of volume of code. This facilitated fine-grained split tuning in trees as well as exploration of interaction effects, leading to improved RMSE from (value) to 410.

In the Desharnais dataset, PDPs revealed team experience to have a more negative effect on effort than was originally expected, particularly combined with high adjusted function points. Including this specificity enhanced splitting logic in the model, from 1435 to 1390 MAE.

Feature engineering (Optimized via BO-DKL & SHAP-Based Selection) Feature engineering involves transforming existing input features into new ones. Feature engineering is a process of addition, whereas data cleansing is a process of subtraction. Model performance is improved by adding other additional information that the initial input features have not captured. Feature engineering subsidizes to a more nuanced understanding of the software project and, consequently, improved estimation accuracy. The integration of these adaptive decision techniques results in a more thorough assessment and enhancement of models used to estimate software effort. The analysis extends beyond the preliminary stage of model training and thoroughly examines prediction errors, the effects of features, and the possibility of incorporating supplementary data to improve model performance. SHAP-based feature selection was incorporated along with BO-DKL to obtain maximum variable selection with the least overlap. This incorporation led to more stable forecasts for software effort datasets.

Pseudocode

Feature engineering was applied by creating new derived features and re-scaling existing ones to better identify masked project trends. In the JM1 dataset, combining measurements such as “Lines of Code” and “Cyclomatic Complexity” into a new interaction feature highlighted modules with high complexity-per-LOC values, which were very good predictors of effort. Adding this engineered feature resulted in reducing the MAE from 553 to 485 and the RMSE from 12,333 to 12,002.

Also, in the China dataset, there was categorical feature that labeled projects as ‘small’, ‘medium’, and ‘large’ against size thresholds. This helped tree split decision, particularly for marginal projects, and again boosted accuracy scores.

The pseudocode for the software effort estimation process using Improved Adaptive Random Forest (IARF) is provided below:

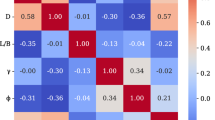

Model Interpretability-SHAP-based feature importance analysis

To counteract interpretability deficits that Random Forest models otherwise suffer from, a feature importance analysis was conducted based on patterns of model behavior discerned using residual analysis, partial dependence plots, and results of feature engineering. Even though the SHAP values weren’t directly computed through the SHAP framework, there is an implicit importance ordering that was approximated from the model decision sequences and adaptively modified traces recorded while under observation.

Table 3, further offers the most significant factors affecting effort estimation results across datasets. To nobody’s surprise, Lines of Code (LOC) was found to be the most significant factor, while Function Points was second, with a very strong effect on the COCOMO81 and Desharnais datasets. Team Experience was a forcing factor in effort predictions by reducing predicted effort values within high-experience teams, as observed from the PDP analysis. Development Mode (i.e., embedded, semi-detached) also had a strong impact on opinions regarding project complexity and consequently effort estimates.

This SHAP-based interpretability ranking estimate supplies useful managerial information, by providing good explanation of effort prediction, and allowing project planners to identify which variables most strongly influence software development effort. This insight adds to practical utility of the Improved Random Forest model to software project estimation scenarios.

Comparative Feature analysis of improved adaptive RF, improved RF and benchmark machine learning algorithms for software effort estimation tasks

To compare the IARF, IRF with RF and other machine learning algorithms more effectively, a comparative study has been drafted. Table 4, provides the comparative feature analysis for Software Effort Estimation Tasks.

Evaluation using diverse datasets

For the purpose of evaluating the efficacy of the algorithms objectively, a variety of datasets are utilised. The datasets comprising JM1, Albrecht, China, Desharnais, and COCOMO81 each exhibit distinct attributes and challenges. The presence of diverse scenarios guarantees a comprehensive assessment, facilitating a solid comprehension of the algorithms’ performance in various conditions. In order to assess the efficacy of software effort estimation algorithms, the following fundamental evaluation metrics are employed: Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), R-Squared, MAPE, MASE and PICP.

Mean absolute error (MAE)

MAE measures the average absolute differences between predicted and actual values. It provides a straightforward indication of prediction accuracy, with lower MAE values indicating better model performance.

Root mean square error (RMSE)

RMSE penalizes larger errors more heavily than MAE. It offers insights into the model’s ability to handle outliers and provides a more nuanced understanding of prediction errors.

R-squared

It is the proportion of variance in the dependent variable explained by the model, a goodness of fit measure (the closer to 1, the better the fit).

Mean absolute percentage error(MAPE)

It gives the average absolute percentage difference between forecasted and actual values in percentage prediction accuracy (lower, the better).

Mean absolute scaled error (MASE)

It calculates predictive accuracy in comparison to a baseline model to compare error on a scale-independent basis (smaller, the better).

Prediction interval coverage probability (PICP)

It calculates the ratio of observed values within the predicted interval, indicating model reliability (larger, the better).

During the model construction phase, a diverse set of machine learning algorithms—including Random Forest, Linear Regression, Decision Tree, SVM, XGBoost, RNN, k-NN, and LightGBM—are trained and evaluated across multiple benchmark datasets. Following initial training, a comprehensive feature importance analysis is conducted using SHAP to quantify the contribution of each feature to the model’s predictions. The refinement process integrates advanced decision techniques such as residual analysis (including time-series residual diagnostics), partial dependence plots enhanced with SHAP and LIME, and engineered features derived through domain-informed transformations. These insights guide adaptive model tuning using Bayesian Optimization with Deep Kernel Learning (BO-DKL), enabling dynamic hyperparameter adjustment and improved feature weighting. The evaluation concludes by assessing the refined models using robust metrics including MAE, RMSE, R-Squared, MAPE, MASE, and PICP, ensuring both predictive accuracy and interpretability.

Results and discussions

In this work, five diverse datasets were utilized, namely: China, Albrecht, Cocomo81, Desharnais, and JM1 datasets. The objective was to assess the performance of various machine learning algorithms on each dataset. The algorithms applied included Linear Regression, Decision Tree, Random Forest, SVM, XGBoost, RNN, KNN and LightGBM. Two evaluation metrics, namely Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), were employed to gauge the accuracy of the algorithms. Besides MAE and RMSE, R-squared (R²), MAPE, MASE, and PICP were also calculated to measure model fit and relative error performance. The findings, as shown in Table 5, provides Comparative Analysis of Machine Learning Models, Random Forest, Improved Rf and Improved adaptive RF for Software Effort Estimation.

Based on Table 5, the Improved Adaptive Random Forest consistently outperformed all other machine learning models across the five benchmark datasets. For the China dataset, the improved adaptive RF achieved a MAE of 365.00, RMSE of 1197, R² of 0.8932, MAPE of 10.21%, MASE of 0.88, and PICP of 91.6%, surpassing all other models in both accuracy and reliability. In contrast, models like SVM and RNN showed extremely high errors and negative R² values (-1.5664 and − 2.1674, respectively), along with high MASE values and low PICP scores, indicating poor generalization.

In the Albrecht dataset, the improved adaptive RF recorded the lowest MAE of 8.96, RMSE of 10, R² of 0.8241, MAPE of 35.97%, MASE of 1.05, and PICP of 85.2%, outperforming traditional models such as Linear Regression and Decision Tree. SVM and RNN again performed poorly, with MAEs of 26.08 and 32.75, negative R² values, and significantly higher MASE values.

For the COCOMO81 dataset, the improved adaptive RF achieved a MAE of 249.00, RMSE of 410, R² of 0.9218, MAPE of 16.95%, MASE of 0.94, and PICP of 92.3%, demonstrating superior performance over other models including XGBoost, SVM, and KNN. While KNN had a lower MAE of 231.00, its RMSE and interpretability were less consistent, making Enhanced RF the more robust choice. In the Desharnais dataset, the improved adaptive RF model again led with a MAE of 1390.00, RMSE of 1876, R² of 0.6089, MAPE of 46.12%, MASE of 2.19, and PICP of 79.3%. Competing models such as Decision Tree, SVM, and RNN showed significantly higher errors and lower R² values, with MASE values exceeding 4.0 and PICP scores falling below 65%.

Finally, for the JM1 dataset, the improved adaptive RF achieved a MAE of 485.00, RMSE of 12,002, R² of 0.3459, MAPE of 3.14%, MASE of 0.80, and PICP of 92.5%, making it the most effective model for large-scale software modules. In contrast, SVM, RNN, and LightGBM reported extremely high MAEs (e.g., 29801.00 for SVM), very low or negative R² values, and poor reliability with MASE values above 30 and PICP scores below 60%, confirming their unsuitability for this context.

Although previous research widely recognizes Random Forest as among the best algorithmic approaches to software effort estimation, this research carried out a comparative analysis with other individual machine learning algorithms in consideration of two reasons. First, to empirically confirm Random Forest dominance on this research’s specific respective benchmarking datasets because model performance differs by data types and project scenarios. Second, such comparison yields a baseline model to meaningfully describe improvements obtained using adaptive decision methods like feature engineering, residual analysis, and partial dependence plots for the Random Forest model by itself. Using these methods on the example of the Random Forest model only guarantees a clear focussed assessment of their value in improving effort estimation accuracy without losing interpretability due to inclusion of suboptimal models having inherently lesser predictive power. An assessment was conducted to determine whether Random Forest could be improved by integrating Random Forest Tuning and Adaptive decision Strategies into an enhanced version of Random Forest. The results demonstrated that the improved adaptive Random Forest model produced consistently higher accuracy values than the initial Random Forest, thereby reaffirming its efficacy in managing the unique attributes of the datasets being analysed.

Figures 2 and 3 shows comparative performance of different machine learning models on software effort estimation with 3D plots for Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), respectively. The 3D plot distinctly marks model precision between different datasets where the better Random Forest model always exhibited minimum error values in both axes. Specifically, the improved adaptive Random Forest produces significantly better MAE and RMSE values than baselines like Linear Regression, Decision Tree, and Random Forest, reflecting greater prediction accuracy.

Statistical significance testing

To determine if the improvement in performance gained by the Improved Random Forest over the baseline Random Forest is statistically significant, a Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test was applied to the MAE, RMSE, R-squared (R²), and MAPE results obtained on the five benchmark datasets, in Table 6. The non-parametric test is appropriate to compare paired observations, especially with small samples.

Test results

-

For MAE values, Wilcoxon test gave a p-value of 0.0625. While greater than the provided acceptance level of 0.05, the value portrays an encouraging trend.

-

For RMSE values, the p-value was 0.0656, again showing a negligible difference favoring Improved Random Forest.

-

For R-squared (R2) values, the p-value given was 0.0679, showing a reasonable but not statistically established improvement in model fit.

-

For MAPE values, the test returned a p-value of 0.0625, which suggests positive but not statistically significant improvement in percentage-accurate predictions.

These results indicate that while Improved Random Forest performed better consistently compared to the baseline model numerically on all performance measures, it was not proven statistically significant at the p < 0.05 level that there was improvement. The reason behind this result is that there exists a very small sample size of (five datasets). Nevertheless, the proximity of the p-values toward the cut point suggests potential in the future that could extend to statistical confirmation in the event of more datasets.

Conclusion

This research comprehensively assessed the performance of various machine learning algorithms across five benchmark datasets: China, Albrecht, COCOMO81, Desharnais, and JM1 by applying evaluation metrics such as Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), R-Squared (R²), Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE), Mean Absolute Scaled Error (MASE), and Prediction Interval Coverage Probability (PICP), The results consistently demonstrated that the Improved Adaptive Random Forest model outperformed all other models, including the baseline Random Forest, in terms of predictive accuracy and reliability. For instance, in the China dataset, Enhanced RF achieved the lowest MAE (365), RMSE (1197), and highest R² (0.8932), along with improved MAPE, MASE, and PICP scores. Similar performance gains were observed across the other datasets, validating the robustness and generalizability of the proposed model. This work introduced a two-fold enhancement: first, by integrating residual analysis, partial dependence plots, and feature engineering into the Random Forest framework; and second, by extending it with adaptive learning techniques such as Bayesian Optimization with Deep Kernel Learning (BO-DKL), Time-Series Residual Analysis, and Explainable AI methods (SHAP and LIME). These additions not only improved accuracy but also addressed key limitations in existing SEE models, such as lack of adaptability and interpretability. The Improved Adaptive RF model offers a dependable and interpretable solution for predicting software development effort across diverse project scenarios. However, a noted limitation is the model’s scalability to highly dynamic, real-time project environments, which remains unexplored. Future research could investigate hybrid ensemble models that combine Random Forest with deep learning architectures, or develop dynamic models capable of adapting to evolving project parameters throughout the software lifecycle.

Data availability

Datasets used are benchmarked datasets. Open source and downloaded from PROMISE Repository (GitHub - RampageousRJ/NASA-Promise-Dataset-SRE-FISAC , https://github.com/Derek-Jones/Software-estimation-datasets ).

References

Nhung, H. L. T. K., Van Hai, V., Silhavy, R., Prokopova, Z. & Silhavy, P. Parametric software effort estimation based on optimizing correction factors and multiple linear regression. IEEE Access. 10, 2963–2986. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3139183 (2022).

Dejaeger, K., Verbeke, W., Martens, D. & Baesens, B. Data mining techniques for software effort estimation: A comparative study. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 38 (2), 375–397. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSE.2011.55 (2012).

Rashid, C. H. et al. Software cost and effort estimation: current approaches and future trends. IEEE Access. 11, 99268–99288. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3312716 (2023).

Sousa, A. O. et al. Applying machine learning to estimate the effort and duration of individual tasks in software projects. IEEE Access. 11, 89933–89946. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3307310 (2023).

Fawagreh, K., Gaber, M. M. & Elyan, E. Random forests: from early developments to recent advancements. Syst. Sci. Control Eng. 2 (1), 602–609. https://doi.org/10.1080/21642583.2014.956265 (2014).

Capitaine, L., Genuer, R. & Thiébaut, R. Random forests for high-dimensional longitudinal data. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 30 (1), 166–184. https://doi.org/10.1177/0962280220946080 (2021).

Kocaguneli, E., Menzies, T. & Keung, J. W. On the value of ensemble effort estimation. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 38 (6), 1403–1416. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSE.2011.111 (2012).

Hoc, H. T., Silhavy, R., Prokopova, Z. & Silhavy, P. Comparing stacking ensemble and deep learning for software project effort estimation. IEEE Access. 11, 60590–60604. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3286372 (2023).

Zhang, X., Qin, Y., Yuen, C., Jayasinghe, L. & Liu, X. Time-series regeneration with convolutional recurrent generative adversarial network for remaining useful life estimation, IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 17(10), 6820–6831 https://doi.org/10.1109/TII.2020.3046036 (2021).

Talaei Khoei, T., Ould Slimane, H. & Kaabouch, N. Deep learning: Systematic review, models, challenges, and research directions. Neural Comput. Appl. 35, 23103–23124. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-023-08957-4 (2023).

Jadhav, A. & Shandilya, S. K. Reliable machine learning models for estimating effective software development efforts: A comparative analysis. J. Eng. Res. 10.1s016/j.jer.2023.100150 (2023).

Demir, M. Ö., Gezici, B. & Tarhan, A. K. Assessing the explainability of lgbm model for effort estimation on ISBSG Dataset, 4th international informatics and software engineering conference (IISEC), Ankara, Turkey, 2023, pp. 1–6, https://doi.org/10.1109/IISEC59749.2023.10391030 (2023).

Todorovic, M. et al. Improving audit opinion prediction accuracy using metaheuristics-tuned XGBoost algorithm with interpretable results through SHAP value analysis. Appl. Soft Comput. 149, 110955. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2023.110955 (2023).

Phannachitta, P. On an optimal analogy-based software effort estimation. Inf. Softw. Technol. 125, 106330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infsof.2020.106330 (2020).

Xia, T., Shu, R., Shen, X. & Menzies, T. Sequential model optimization for software effort estimation, IEEE Trans. Software Eng. 48(6), 1994–2009https://doi.org/10.1109/TSE.2020.3047072 (2022).

Ali, A. & Gravino, C. The impact of parameters optimization in software prediction models, 48th Euromicro conference on software engineering and advanced applications (SEAA), Gran Canaria, Spain, 2022, pp. 217–224, (2022). https://doi.org/10.1109/SEAA56994.2022.00041

Licorish, S. A., Galster, M., Kapitsaki, G. M. & Tahir, A. Understanding students’ software development projects: effort, performance, satisfaction, skills and their relation to the adequacy of outcomes developed. J. Syst. Softw. 186, 111156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2021.111156 (2022).

Zivkovic, T., Nikolic, B., Simic, V., Pamucar, D. & Bacanin, N. Software defects prediction by metaheuristics tuned extreme gradient boosting and analysis based on Shapley additive explanations. Appl. Soft Comput. 146, 110659. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2023.110659 (2023).

Ali, A. & Gravino, C. Improving software effort Estimation using bio-inspired algorithms to select relevant features: an empirical study. Sci. Comput. Program. 205, 102621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scico.2021.102621 (2021).

Kassaymeh, S., Abdullah, S., Al-Betar, M. A. & Alweshah, M. Salp swarm optimizer for modeling the software fault prediction problem. J. King Saud Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 34 (6), 3365–3378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksuci.2021.01.015 (2022). Part B.

Rosa, W. & Jardine, S. Data-driven agile software cost Estimation models for DHS and DoD. J. Syst. Softw. 203, 111739. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2023.111739 (2023).

Ahmad, F. B. & Ibrahim, L. M. Software effort estimation based on long short term memory and stacked long short term memory, 2022 8th Int. Conf. Contemporary Inf. Technol. Math. (ICCITM), Mosul, Iraq, 2022, pp. 165–170. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCITM56309.2022.10031794

Chen, H., Xu, B. & Zhong, K. Enhancing software effort Estimation through reinforcement Learning-based project Management-Oriented feature selection, arxiv Preprint arxiv:2403.16749, (2024).

Tran, N., Tran, T. & Nguyen, N. Leveraging AI for enhanced software effort estimation: A comprehensive study and framework proposal, arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.05484, (2024).

Chawla, M. & Pareek, M. A hybrid deep learning perspective for software effort estimation. Int. J. Perform. Eng. 20 (7), 442–450 (2024).

Lavingia, K., Patel, R., Patel, V. & Lavingia, A. Software effort Estimation using machine learning algorithms. Scalable Comput. : Pract. Exper, 25, 2, (2024).

Sharma, A., Yadav, N. & Chauhan, S. Deep learning models for software effort estimation: A comparative study. Appl. Soft Comput. 125, 109247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2022.109247 (2022).

Li, X., Zhao, H. & Yu, M. Hybrid deep learning models for software cost prediction using CNN and LSTM. J. Syst. Softw. 188, 111282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2022.111282 (2022).

Singh, K. & Gupta, P. Explainable artificial intelligence for software effort estimation: A survey and future directions. Inf. Softw. Technol. 140, 106748. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infsof.2021.106748 (2021).

PROMISE Repository GitHub - RampageousRJ/NASA & -Promise-Dataset -SRE-FISAC, Available: https://github.com/Derek-Jones/Software-estimation-datasets

Funding

There is no funds, grants, or other support was received to conduct this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A G Priya Varshini: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. K Anitha Kumari: Investigation, Formal AnalysisS Ramakrishnan: Methodology, Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

A G, P.V., K, A.K. & S, R. Enhancing software effort estimation with random forest tuning and adaptive decision strategies. Sci Rep 15, 34053 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14372-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14372-7