Abstract

By conducting push-out tests, the bond behavior between H-shaped steel and concrete under different freeze-thaw (F–T) cycles (including failure modes, bond strength, and bond stress-slip curves) was investigated. The experiment considered one type of concrete (C35), three volumetric stirrup ratios (0.4%, 0.8%, and 1.2%), and three F–T levels (0, 25, and 50 cycles). Based on the experimental results, the effects of F–T cycles and stirrup ratio on the bond performance were systematically analyzed. The results showed that prior to F–T exposure, specimens with a stirrup ratio of 0.8% and an anchorage length of 380 mm / 560 mm exhibited splitting failure, while specimens with a stirrup ratio of 0.4% and an anchorage length of 380 mm experienced pull-out failure. As the number of F–T cycles increased, the failure mode shifted from splitting failure to push-out failure. After 50 F–T cycles, the bond strength of specimens with 380 mm and 560 mm anchorage lengths decreased to 82.2% and 84.7%, respectively, compared to the unexposed condition. Under the same F–T conditions, the pull-out force and bond strength of specimens with a 1.2% stirrup ratio were higher than those with 0.4%. The bond stress-slip curve shape remained generally consistent before and after F–T cycles, but the peak stress decreased and the slip at the peak load increased with more cycles. A regression model was also developed to describe bond strength degradation, providing a basis for predicting long-term performance. These findings clarify the deterioration pattern of steel–concrete bond under F–T conditions and offer a technical reference for the safety and durability assessment of composite structures in cold regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Steel-reinforced concrete (SRC) structures combine the advantages of steel and reinforced concrete, resulting in a synergistic effect. SRC structures are known for their high rigidity, which allows them to effectively resist external loads and provide exceptional seismic response capabilities. Additionally, their improved fire resistance ensures good performance in emergencies such as fires1,2. Compared to conventional reinforced concrete (RC) structures, SRC structures offer greater load-bearing capacity, better ductility, superior seismic performance, and a higher damping ratio3,4,5,6. As a result, SRC structures have been widely applied in the construction industry7,8,9,10,11.

The overall mechanical behavior of SRC structures depends not only on the properties of the materials, but also on the bond performance at the steel–concrete interface12,13,14,15. This bonding action allows the two materials to fully leverage their respective advantages and share the load16. Ensuring sufficient bond strength and rigidity within SRC structures is therefore crucial for the effective transfer of shear forces17,18,19,20. The bond behavior between profiled steel and concrete is influenced by many factors. These include concrete cover thickness, concrete strength, steel corrosion, anchorage conditions, and volumetric stirrup ratio10,21,22. Together, these factors affect the overall performance of steel-reinforced concrete structures and are vital for ensuring their stability and reliability.

Pollutant transport in concrete pores is critical for assessing the durability of steel-concrete composites23. Studies have shown that water permeability is related to the pores in the 10–100 nm and 100–1000 nm ranges, while gas permeability is mainly influenced by the 100–1000 nm pores24. In the interception wall system, the permeability of pollutants is closely related to the permeability coefficient of the low-permeability layer.

When the permeability coefficient (k₂) is 2 × 10⁻⁹ m/s, about 53% of the pollutant flux passes through the weakly permeable layer25. In coarse aggregate media, pollutant migration can be 10 times faster than in fine aggregate26. In unsaturated concrete, pore distribution governs the convective diffusion behavior of chloride ions27. Additionally, the adoption of biomimetic technology is an important strategy to improve the durability of concrete and reduce maintenance costs. Biomimetic approaches, such as gradient-responsive repair materials inspired by plant conduits and shell structures, have been shown to improve concrete durability28. The self-healing system inhibits water intrusion by actively sealing cracks29,30 but low-temperature environments significantly suppress microbial metabolic activity29. Moreover, environmental factors have a significant regulatory effect on the self-healing process26.

The regeneration of microcracks caused by F–T cycles may exceed the capacity of concrete’s self-healing mechanisms. In addition to F–T effects, environmental actions such as sulfate attack, carbonation, and ion penetration influence the strength, permeability, and microstructure of concrete. Akbarpour and Mahdikhani31 found that replacing up to 20% of cement with natural zeolite improved the long-term mechanical strength and reduced permeability of cement–bentonite cutoff walls due to enhanced sulfate resistance. Akbarpour et al.32 reported that zeolite-modified plastic concrete showed increased strength and stiffness under sulfate ion exposure, which they attributed to reduced porosity and refined microstructure. Akbarpour et al.33 further demonstrated, through SEM analysis, that specimens cured in sulfate environments developed lower porosity, leading to improved unconfined strength, elastic modulus, and reduced permeability. Meanwhile, Akbarpour et al.34 highlighted that incorporating carbon fiber-reinforced polymer (CFRP) bars and wraps substantially improved the flexural performance of RC beams. Although porosity was not directly measured, the enhanced performance was partly attributed to improved crack control and increased microstructural integrity, which are indirectly related to reduced porosity and enhanced durability under aggressive conditions.

The SRC structures in cold and extremely cold regions are significantly affected by F–T cycles. F–T cycles, driven by temperature fluctuations, cause water in concrete pores to repeatedly freeze and thaw, seriously degrading SRC structural performance35. This process damages concrete and weakens the steel-concrete bond, leading to irreversible degradation and reduced durability36. Existing research indicates that F–T cycles significantly reduce the bond strength of ordinary concrete, while air-entrained concrete and SHCC-repaired concrete exhibit better crack resistance under F–T conditions. Increasing the stirrup ratio can further enhance bonding performance. An increased number of F-T cycles significantly reduces the bond strength between recycled aggregate concrete and deformed steel bars37,38.

Recent studies have shown that freeze–thaw cycles affect the steel–concrete interface at the macro and micro scales, causing pore enlargement, interfacial microcracking, and redistribution or loss of hydration products. These microstructural changes contribute to the degradation of interfacial bonding properties. Additionally, several numerical models have been developed to simulate the freeze–thaw damage process in steel–concrete composite systems, enabling the prediction of long-term bond strength deterioration under repeated environmental loading. Research has also investigated the evolution of bond strength under cyclic conditions, including degradation rates, crack propagation behavior, and adhesion loss over time. Although bonding performance between steel and concrete has been relatively well studied, there remain gaps in understanding the degradation mechanism of the interface between H-shaped steel and concrete under freeze–thaw cycles. Guo9 and Yao et al.39 conducted pull-out tests on H-shaped steel–concrete specimens and found that the number of freeze–thaw cycles is negatively correlated with the interfacial bond strength. In addition, the anchorage length of the steel section is negatively correlated with the ultimate bearing capacity of the specimen, while the reinforcement ratio is positively correlated with the bond strength. However, most studies focus on macroscopic mechanical behavior, with limited understanding of bond stress redistribution and its degradation under freeze–thaw damage. This highlights a specific research gap regarding the underlying mechanism of interfacial bond degradation under freeze–thaw cycles, particularly in H-shaped steel–concrete systems.

Although numerous studies have investigated the bond performance between steel bars and concrete under F–T conditions, the interfacial degradation mechanisms specific to H-shaped steel–concrete systems remain inadequately understood. Moreover, there is a lack of comprehensive analysis on the combined effects of stirrup ratio and anchorage length on bond degradation during repeated F–T cycles.

The objective of this study is to quantify the degradation of bond strength at the interface between H-shaped steel and concrete under different numbers of F–T cycles. It also aims to investigate the effects of stirrup ratio and anchorage length on the evolution of interfacial damage. Bond behavior was examined after 0, 25, 50, 100, and 200 F–T cycles. The results enhance the understanding of the interfacial bond degradation mechanism between H-shaped steel and concrete under F–T cycles, and support the durability design of composite structures in cold regions.

Experimental details

Materials and mix ratios

During the experiment, 1) ordinary Portland cement (grade 42.5R) grade complying with “Common portland cement” GB175-200740 was used; 2) the fine aggregate is artificial sand with a fineness modulus of 2.7, as shown in Fig. 1a and 3) the coarse aggregate was crushed stone with a maximum particle size of 40 mm, as depicted in Fig. 1b and 4) the mixing water was ordinary tap water, with a water-to-cement ratio of 0.40; (5) HRB335 deformed bar with a diameter of 6 mm were arranged at 120 mm spacing as the hoop reinforcement, while deformed bar with a diameter of 8 mm and a yield strength of 400 MPa were used as longitudinal reinforcement; (6) as shown in Fig. 2a, the profiled steel used was Q345 hot-rolled H-shaped steel with specifications of HW200 × 200 × 8 × 12. The casting mould for the specimen, shown in Fig. 2b, was made of wood with a thickness of 2 cm and an overall size of 384 × 384 × 402 mm. A 2 cm-thick foam board was placed at the bottom of the mould to ensure that the bottom steel section protruded by 2 cm. Four triangular wooden blocks were used at the top of the mould to tightly grip the and prevent expansion or leakage. Before pouring, the interior of the mould was evenly brushed with oil to facilitate demolding without damaging the specimen. A steel bar frame was used to clamp the outside of the mould to prevent expansion during the pouring. (7) A polycarboxylate superplasticizer was added to the concrete mixture to reduce water content, and fly ash was incorporated as a mineral admixture. Table 1 lists the mix proportions by weight of the concrete mixture.

Sample selection

The volumetric stirrup ratios of 0.4%, 0.8%, and 1.2%, along with anchorage lengths of 380 mm and 560 mm, were selected based on references9 and27. These values were chosen to represent typical reinforcement and anchorage conditions encountered in engineering practice. Specifically, the two anchorage lengths correspond to commonly adopted short and long anchorage configurations in SRC members, enabling the assessment of bond performance variation under F–T conditions. The combined variations in stirrup ratios and anchorage lengths were designed to simulate realistic reinforcement layouts and bonding scenarios typically observed in cold-region constructions.

Samples and testing programs

The preparation and curing process of the specimens followed these steps: (1) the entire profiled steel was cut to the predetermined anchorage length to ensure compliance with the specifications (Fig. 3a); prior to casting, the surface of the H-shaped steel was manually treated using a wire brush to remove rust, oil, and debris, ensuring a clean and roughened surface condition to promote effective bonding with concrete; (2) the cut longitudinal and stirrup rebars were processed and tied into a rebar cage, ensuring that the cage had an adequate protective layer thickness (Fig. 3b); (3) wooden moulds were fabricated according to the design dimensions of the specimens (Fig. 3c); (4) the profile of the profiled steel was cut out on a foam board to ensure that the steel was centred within the specimen and that the prefabricated rebar cage was properly positioned in the mould (Fig. 3d); (5) the mixed concrete was poured into the mould, and after vibrating, a wet cloth was placed over the surface of the specimen to prevent moisture evaporation (Fig. 3e); (6) following the “Standard for Test Methods of Physical and Mechanical Properties of Concrete” GB/T50081-2019 41, the specimens were cured in an environment of 20 ± 5 °C and relative humidity greater than 50% for 2 days, after which the moulds were removed when the specimens reached a specific strength (Fig. 3f); and (7) according to the “Standard for Test Methods of Long-Term Performance and Durability of Ordinary Concrete” GB/T 50082-200 42, the specimen was extracted from the wooden mold and maintained for 28 days under conditions of 95% RH and a temperature range of 20 ± 3 °C (Fig. 3g).

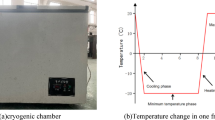

According to the “Standard for Test Methods of Physical and Mechanical Properties of Concrete”41 the push-out test method was employed. Figure 4 shows the specimen for the push-out test. Figure 5 provides a schematic of the dimensions of the push-out specimen. The specimens were soaked in water for 4 days before undergoing F–T cycling. Subsequently, the water-soaked concrete specimens were placed in an F–T testing apparatus and subjected to F–T cycle tests in accordance with GB/T 50082 − 200942. A total of 0, 25, and 50 F–T cycles were applied to simulate varying degrees of environmental degradation. In cold regions such as Changchun in northeastern China, approximately 30–60 natural F–T cycles occur annually; thus, the 50-cycle condition reasonably represents one year of actual exposure. During the F–T cycles, the concrete specimens were placed in a small, lidless box with internal dimensions of 40 × 40 × 50 cm, a bottom plate made of 5 mm-thick steel, and sides constructed of 3 mm-thick steel. During the F–T cycle test, the central temperature of the concrete specimen was monitored by a platinum thermal sensor embedded in a 380 mm x 380 mm x 400 mm prism at the center of the specimen. After an F–T cycle, the center temperature of the prism specimen was dropped from 3 ± 2 °C to -11 ± 2 °C and then rose to 8 ± 2 °C for 3 h. Figure 6 shows the specimen and Pt sensor in the F–T testing apparatus.

A 520 mm length of steel was embedded into a concrete cube with dimensions of 380 × 380 × 400 mm, with 400 mm as the anchorage length for the bonding performance test. Figure 7 shows the push-out test setup. Linear Variable Differential Transformers (LVDTs) were installed at the loading point and the free end of the specimen to measure the relative slip between the H-shaped steel and the concrete.

Experimental results and data analysis

Specimen failure mode

Xie et al.43 conducted pull-out tests on steel-reinforced concrete and identified three main failure modes: (1) Bond-splitting failure. Upon reaching approximately 80% of the ultimate load, vertical cracks begin to appear on the inner side of the protective layer at the edge of the steel flange. As the load further increases, these cracks gradually expand outward at approximately a 45° angle or parallel to the direction of the profiled steel, and extend along its length. (2) Bond-anchorage failure, also known as push-out or pull-out failure. Upon reaching approximately 80% of the ultimate load, microcracks perpendicular to the flange’s edge begin to appear in the marginal protective layer of the steel flange. Shear cracks on the inner side of the steel’s protective layer predominantly extend along the entire length of the steel within a narrow thickness range, while also slightly expanding towards the outer side of the protective layer. (3) Profiled steel yielding failure, which occurs after the profiled steel itself yields.

According to the test results, it can be seen that the failure mode did not undergo a significant change after a lower number of F–T cycles. The specimens consistently exhibited a failure mode of push-out for steel sections with an anchorage length of 400 mm embedded in concrete after undergoing various F–T cycles. Figure 8 presents the typical push-out failure cross-sections of the profiled steel embedded in concrete after 0, 25, and 50 F–T cycles. From Fig. 8, it can be seen that before the F–T cycle, the crack at the top of the specimen is relatively small, primarily oriented perpendicular to the flange, indicating that the structural integrity of the concrete is maintained in the initial state, and its failure mode is primarily push-out failure. After 25 F–T cycles, vertical splitting cracks appeared at the top of the specimen, caused by F–T damage, and extended from the top toward the sides, forming through cracks. This finding suggests that the specimen’s failure pattern progresses from crack development to initial degradation in bonding performance as the number of F–T cycles increases. After 50 F–T cycles, small initial cracks were observed at the end of the top flange. The crack development of the specimen was still relatively limited, but the damage to the bottom concrete was more severe. Although the bond performance further decreased, crack development was not pronounced, and the failure mode remained push-out failure. Therefore, F–T cycles have a particular impact on the failure mode at the interface between H-shaped steel and concrete. As the number of F–T cycles increases within a specific range, the interfacial bond performance gradually decreases, and the crack expansion pattern exhibits different characteristics, but the failure mode does not change.

Guo9 conducted 0, 50, 100, and 200 F–T cycle push-out tests on concrete specimens with profiled steel anchorage lengths of 380 mm and 560 mm and volumetric stirrup ratios of 0.4%, 0.8%, and 1.2%. For specimens with a volumetric stirrup ratio of 0.4%, the failure mode was push-out failure after 50 F–T cycles. For specimens with a volumetric stirrup ratio of 0.8% and a profiled steel anchorage length of 380 mm, the failure mode was splitting failure before F–T cycling, which changed to push-out failure after 100 and 200 F–T cycles. However, after 50 F–T cycles, one of the three specimens exhibited splitting failure, while the remaining two specimens exhibited push-out failure. For specimens with a volumetric stirrup ratio of 0.8% and a profiled steel anchorage length of 560 mm, splitting failure was observed before F–T cycles, and it changed to push-out failure after 50, 100, and 200 F–T cycles.

Bond strength

In this study, the average bonding stress at the interface between steel and concrete is defined as:

where τ represents the average bond stress in units of MPa; P is the load applied at the loading end in units of kN; C is the circumference of the profiled steel cross-section in units of mm; and l is the bond length of the profiled steel in units of mm.

The bond strength test results between the profiled steel and the concrete after F–T cycling are presented in Table 2. The specimen numbering follows the format “F200V08L560-3”, where “F200” indicates 200 freeze–thaw cycles, “V08” denotes a volumetric stirrup ratio of 0.8%, “L560” specifies an anchorage length of 560 mm, and “-3” represents the third parallel specimen in the group. An asterisk (“*”) indicates data obtained from the present experiments, while the remaining values were adopted from reference9; however, all the failure modes were re-examined and consistently reclassified in this study.

Each configuration was tested with 1 to 3 specimens, depending on material availability and experimental feasibility. For groups with multiple specimens, the bond strength is reported as the mean ± standard deviation; for single specimens, the measured value is presented directly without deviation.

The influence of F–T cycles on bonding stress

The impact of F–T cycling on the bond strength between profiled steel with a volumetric stirrup ratio of 0.8% and concrete with anchorage lengths of 380 mm and 560 mm is illustrated in Fig. 9. Table 3 shows the percentage decrease in the bond strength of profiled steel embedded in concrete with anchorage lengths of 380 mm and 560 mm as the number of F–T cycles increases. From Fig. 9 and Table 3, it can be seen that as the number of F–T cycles increases, the bond strength decreases. The specimens with a profiled steel anchorage length of 380 mm show a greater reduction in bond strength than those with an anchorage length of 560 mm. After 50 F–T cycles, the bond strength between the steel shapes with anchorage lengths of 380mm and 560mm and the concrete decreased to 82.2% and 84.7% of their initial strength, respectively. After 100 F–T cycles, the bond strength between the steel shapes with anchorage lengths of 380mm and 560mm and the concrete decreased to 75.3% and 78.6% of its initial strength, respectively. After 200 F–T cycles, the bond strength decreased to 67.2% and 71.7% of the precycle strength for anchorage lengths of 380 mm and 560 mm, respectively.

According to the experimental results of this study, after 25 and 50 F–T cycles, the bond strengths of the profiled steel-concrete with an anchorage length of 400 mm were 98.8% and 64.3%, respectively, of their initial value before the F–T cycling. Yao et al.39 used the same experimental method to investigate the bond strength after 0, 50, and 100 F–T cycles for profiled steel with anchorage lengths of 380 mm and 560 mm. The conclusion remains the same: with an increase in the number of F–T cycles, the decline in the specimen’s bond strength intensifies. As the number of F–T cycles increases, the accumulation of damage leads to the expansion and penetration of cracks in the concrete44 which reduces the chemical bonding force, mechanical interlock, and friction of the contact surface between the steel and the concrete to varying degrees9thus reducing the bonding stress between the steel and the concrete.

Potential sources of error include variations in specimen preparation, such as mixing and reinforcement placement, which could affect bond strength measurements. Inconsistent material distribution or specimen geometry could also introduce variability. Fluctuations in environmental conditions, particularly temperature and humidity, may affect hydration and strength development, thereby influencing bonding performance. Meanwhile, the brief temperature fluctuation (± 2 °C) of the F–T test device may prolong a single F–T cycle, thereby affecting the degradation of the bond stress between the steel and concrete after F–T.

Influence of stirrup volumetric stirrup ratio on bond strength

The impact of the volumetric stirrup ratio on the bond strength between the profiled steel with an anchorage length of 560 mm and the concrete after 0 and 100 F–T cycles is shown in Fig. 10. As illustrated in Fig. 10, the bond strength tends to increase with the volumetric stirrup ratio. At the same volumetric stirrup ratio, the bond strength decreases as the number of F–T cycles increases. Table 2 shows that after the same number of F–T cycles, the push-out force and bond strength between the profiled steel and concrete with a higher volumetric stirrup ratio are greater than those with a lower volumetric stirrup ratio. For example, before undergoing F–T cycles, the bond strength of a specimen with a volumetric stirrup ratio of 1.2% is 1.08 (1.21) times that of a specimen with a volumetric stirrup ratio of 0.8% (0.4%). This is because the presence of stirrups provides lateral restraint for the interface between steel and concrete. The confining effect of stirrups increases the lateral pressure on the concrete, which helps resist crack formation and reduces the likelihood of debonding. This confinement effect indirectly improves the slip resistance between steel and concrete, leading to increased bond strength. After 100 F–T cycles, the bond strength of the specimen with a 1.2% volumetric stirrup ratio is 1.03 (1.06) times that of the specimen with a 0.8% (0.4%) volumetric stirrup ratio.

According to the research findings of Guo9 the bond strength between profiled steel and concrete with a volumetric stirrup ratio of 0.4% was 82.7% of that with a 1.2% before undergoing F–T cycling. However, after 100 F–T cycles, the bond strength between the profiled steel and concrete with a volumetric stirrup ratio of 0.4% reached 94.3% of that with a volumetric stirrup ratio of 1.2%. This discovery reveals a significant difference in the bond strength between steel and concrete with different volumetric stirrup ratios before and after undergoing F–T cycles. After F–T cycling, specimens with a higher volumetric stirrup ratio exhibited a greater reduction in bond strength than did those with a lower volumetric stirrup ratio. Yao et al.39 used a similar experimental method to explore the relationship between the thickness of the steel protective layer (60 mm, 90 mm, and 120 mm) and the bond strength of concrete after undergoing 100 F–T cycles. The research results show that as the number of F–T cycles increases, the bond strength of specimens with a protective layer thickness of 60 mm, 90 mm, and 120 mm decreases to 80.1%, 80.1%, and 87.3% of their original values, respectively. This phenomenon indicates that an increase in the thickness of the steel protective layer can effectively mitigate the damage caused to concrete specimens by F–T cycling.

Bond stress-slip curve

The measured bond stress-slip curves of steel embedded in concrete at different F–T cycles are shown in Fig. 11. Specifically, Fig. 11a shows the bond stress-slip curves obtained from this study for profiled steel embedded in concrete, while Fig. 11b shows the curves obtained from the literature9corresponding to the specimen marked with “#” in Table 2. A curve in Fig. 11b is obtained by averaging three specimens with the same number of F–T cycles. The bond stress-slip curves in Fig. 11 indicate that, after F–T cycles, both steel-reinforced concrete and recycled concrete exhibit similar behavior to untreated steel-reinforced concrete. Similar results have also been reported in the literature45. The impact of F–T cycling on the bond performance between profiled steel and concrete is evident in the bond stress-slip curves. These changes occur across different phases: microslip, internal cracking, push-out, decline, and residual.

(1) Before F–T cycling, the microslip phase of the bond stress-slip curve shows that when a small thrust is applied at the loading end of the profiled steel, the slip is not significant, and the curve maintains an approximately linear relationship. After the F–T cycles, the slope of this linear segment changes slightly, and the length of the bond stress-slip curve becomes shorter. (2) During the internal cracking stage, as the applied thrust increases, the free end of the steel begins to slip, indicating that the adhesion between the steel and concrete is approaching exhaustion. With further F–T cycles, slip can be observed even with the application of a smaller force. (3) Subsequently, the slip increases significantly, and the rising part of the bond stress slip curve exhibits nonlinear characteristics.4) With F–T cycling, during the bond stress-slip stage of profiled steel, when the applied thrust reaches the peak load, multiple longitudinal splitting cracks appear in the thinnest area of the concrete cover. With the F–T cycles, the peak load decreases, while the peak slip amount increases. 5) In the stage of bond stress-slip reduction before F–T cycles, the thrust applied to the specimen rapidly decreases, and the slip amount of the steel increases until the steel is completely pushed out and the loading stops. Under F–T cycling, the stress decreases more gradually. 6) During the residual phase of the bond stress‒slip, although the applied thrust decreases compared to the peak load, the slip amount significantly increases.

Under F–T cycles, the volume of water in steel-reinforced concrete specimens changes during freezing and thawing, leading to internal damage within the steel-reinforced concrete structures46. As the number of F–T cycles increases, this internal damage expands and progresses. Consequently, a shorter length of the micro-slip section in the bond stress-slip curve indicates that the internal structure of the steel-reinforced concrete specimen becomes relatively loose. Both the freezing of water and the melting of ice crystals cause changes in the internal stress of the steel-reinforced concrete specimen, which can lead to cracking and eventual failure. An increase in F–T cycles decreases the peak load in the bond stress-slip curve corresponding to the slip stage. Jin et al.47 developed a physical model to simulate the internal microstructure of concrete and used an equivalent circuit model to analyze electrochemical impedance spectroscopy results. The findings demonstrated that F–T cycles promote crack propagation within the concrete, leading to a decrease in continuous path resistance, as confirmed by microscopic observations using environmental scanning electron microscopy.

Relationship between bond strength and number of F–T cycles

In order to optimize seismic design and achieve economic balance, combined with experimental results analysis, the bond strength between profiled steel and concrete after different F–T cycles is represented as follows:

For specimens with a profiled steel anchorage length of 400 mm:

For specimens with a profiled steel anchorage length of 560 mm:

where τ is the bond strength and N is the number of F–T cycles. Obtain the correlation coefficient r2 through multiple responses to the experimental data; for specimens with a profiled steel anchorage length of 400 mm, the r2 for the bond strength expression is 1.0, and for specimens with a profiled steel anchorage length of 560 mm, the r2 for the bond strength expression is 0.9.

Discussion

The adhesive strength between steel shapes and concrete is analogous to that between round steel bars and concrete, consisting of the following two components: (1) the chemical adhesion force between profiled steel and concrete, and (2) the frictional force between the contact surface of profiled steel and that of concrete. Furthermore, the variability in bond strength is influenced by multiple factors, with the mechanical properties of concrete specimens being the most significant, particularly their splitting tensile strength.

For profiled steel concrete specimens, F–T cycling can cause microdamage to the concrete, which loosens the internal structure of the concrete. As a result, the mechanical properties such as compressive strength, tensile strength, and splitting tensile strength of concrete specimens decrease to varying degrees, and the chemical bonding force between steel and concrete decreases or even disappears. This weakened internal structure reduces or eliminates the chemical bond between the profiled steel and the concrete. The degradation of bonding performance in the interfacial transition zone (ITZ) between steel and concrete under F–T cycles is the result of both physical deterioration and chemical erosion. As the temperature decreases, the static water pressure generated by the freezing and expansion of pore water and the osmotic pressure generated by the migration of unfrozen water cause the continuous propagation and interconnection of interface microcracks, thereby weakening the chemical bonding force and friction force between the steel and concrete. In addition, the freezing of water can cause changes in the alkaline environment within the micropores, coupled with osmotic pressure, leading to further destabilization of the ITZ structure. The synergistic effect of physical expansion and chemical reaction is the main reason for the attenuation of bond strength in steel-reinforced concrete.

Therefore, when the anchorage length of the steel section remains unchanged, the bond strength between the steel section and the concrete shows a decreasing trend with the increase of F–T cycles. The softening of concrete caused by repeated F–T cycles increases the concrete strain under the same pull-out load, resulting in greater bond slip at peak load48. Hence, F–T cycling affects the mechanical performance of concrete specimens at the macroscale and alters the interaction mechanism between profiled steel and concrete at the microscale. The scientific findings of this study reveal that F–T cycles significantly impact the bonding performance at the steel-concrete interface by causing damage and degradation to the concrete’s internal microstructure. Specifically, F–T cycles loosen the internal structure of the concrete, reducing its compressive, tensile, and splitting tensile strengths, which in turn reduces both the chemical bonding force and the frictional force between the steel and concrete. As the number of F–T cycles increases, these effects become more pronounced, resulting in a gradual reduction in bond strength and an increase in bond slip. These findings provide theoretical guidance for the durability design of steel–concrete structures in F–T environments.

Optimizing the durability of steel-concrete structures in cold regions involves multiple strategies. For concrete, improving the mix design by incorporating admixtures such as fly ash, silica fume, or polypropylene fibers can help reduce permeability, increase F–T resistance, and improve bond strength. A lower water-to-cement ratio and higher cement content can also enhance F–T durability. For steel, surface treatments such as galvanization or corrosion-resistant coatings can mitigate the effects of F–T cycles on the steel-concrete interface. Additionally, increasing the reinforcement ratio or enhancing the steel’s mechanical properties—such as using high-strength steel or corrosion-resistant steel—can further improve the overall durability of the structure.

In terms of interface optimization design, the development of intelligent transition layer materials may become an important research direction. By precisely controlling the porosity and ITZ structure, directional dissipation of F–T stress fields can be achieved. The confining effect of these materials helps reduce crack propagation at the interface. Moreover, antifreeze protective coatings offer not only passive protection but also the potential for dynamic adaptation to environmental changes. Intelligent coatings that adjust interface permeability according to temperature and humidity fluctuations could further mitigate the negative effects of F–T cycles. However, the long-term adhesion and self-healing efficiency of such coatings at extremely low temperatures require further experimental validation, particularly regarding performance degradation mechanisms under F–T cycles.

In the future, machine learning techniques can be employed to build a predictive framework for bond strength degradation between H-shaped steel and concrete under F–T cycles. Inspired by Mojtahedi et al.49relevant input parameters—such as the number of F–T cycles, anchorage length, and volumetric stirrup ratio—can be used to predict bond strength and slip behavior. Algorithms such as support vector machine (SVM), random forest (RF), and multilayer perceptron (MLP) may be adopted to develop the models. The experimental dataset can be divided into training, validation, and test subsets to ensure model accuracy and generalizability. A sensitivity analysis can also be conducted to identify the most influential parameters affecting bond degradation. Once trained and validated, the model could be used to predict interfacial performance under various environmental and structural conditions, providing a reliable reference for durability-based design and maintenance planning in cold-region engineering.

Conclusion

Based on experimental research, it was observed that the bond strength between H-shaped steel and concrete progressively decreased with increasing F–T cycles. After 50 cycles, specimens with anchorage lengths of 380 mm and 560 mm retained 82.2% and 84.7% of their initial strength, respectively, with a more pronounced reduction observed in the shorter anchorage length. Specimens with a 0.8% volumetric stirrup ratio and shorter anchorage lengths (380 mm) exhibited a shift in failure mode from splitting to push-out failure after 100 and 200 cycles, a trend that was also observed in specimens with longer anchorage lengths. A higher stirrup ratio (1.2%) consistently led to better bond performance than a lower stirrup ratio (0.4%), both before and after F–T exposure. Bond stress-slip curves revealed that the peak bond stress decreased and the slip at peak load increased with more F–T cycles. A regression model was developed to quantify the degradation trend, providing a useful tool for long-term performance prediction.

In summary, this study quantitatively evaluated the degradation of steel–concrete bond strength under F–T exposure, revealed the influence of stirrup ratio and anchorage length on bond performance, and proposed a degradation model to support durability-based design. These findings provide a technical reference for the safety and longevity assessment of composite structures in cold climates.

Future research should focus on optimizing the steel–concrete interface, such as enhancing surface roughness or applying antifreeze coatings. Moreover, investigating different concrete types, admixture combinations, and environmental factors (e.g., humidity and temperature) would contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of bonding behavior. Integrating microstructural analysis with numerical simulation is also encouraged to further elucidate the damage mechanisms under F–T action.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable.

References

Chen, Z. et al. Cyclic performance of middle partially encased composite braces. J. Constr. Steel Res. 212, 108250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcsr.2023.108250 (2024).

Li, W. et al. Early-age bond behavior of deformed bars in concrete subjected to bilateral pressures. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 35, 04023235. https://doi.org/10.1061/JMCEE7.MTENG-15179 (2023).

Chen, Y., Zhang, S. & Chen, Z. Experimental study on steel reinforced concrete T-section beam subjected to pure torsion and combined action of bending-torsion. Structures 46, 1000–1015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2022.10.109 (2022).

El-Sayed, T. A. et al. Structural behavior of ultra-high strength concrete columns reinforced with basalt bars under axial loading. Int. J. Concr Struct. Mater. 17 (43). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40069-023-00600-9 (2023).

Lai, B. L., Yang, L. & Xiong, M. X. Numerical simulation and data-driven analysis on the flexural performance of steel reinforced concrete composite members. Eng. Struct. 247, 113200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2021.113200 (2021).

Zhang, J. et al. push-out tests of interfacial bond slip between H-shaped steel and ultra-high performance concrete. Structures 57, 105268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2023.105268 (2023).

Elmy, M. H. & Nakamura, S. Static and seismic behaviours of innovative hybrid steel reinforced concrete Bridge. J. Constr. Steel Res. 138, 701–713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcsr.2017.08.025 (2017).

Zhuang, B. et al. Study on the composite mechanism of large rubber-sleeved stud connector. Constr. Build. Mater. 211, 869–884. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.03.303 (2019).

Guo, Y. Study on bond slip behavior of steel reinforced concrete after freeze-thaw cycle effect. Master’s thesis, Ningbo University (in Chinese) (2018).

Wang, X. et al. Effect of concrete cover on the bond-slip behavior between steel section and concrete in SRC structures. Constr. Build. Mater. 229, 116855. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.116855 (2019).

Zhang, L. et al. Bond-slip behavior between reactive powder concrete and H-shaped steel. J. Constr. Steel Res. 210, 108058. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcsr.2023.108058 (2023).

Ming, M. et al. Experimental study on the bond-slip behavior and stress transfer mechanism between shaped steel and high-performance fiber-reinforced concrete. Structures 34, 5013–5028. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2021.09.014(2021).

Wang, C. et al. Bond behavior between section steel and concrete in partially encased composite structural members. Constr. Build. Mater. 400, 132521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.132521 (2023).

Wang, W. H. et al. Tests on the steel-concrete bond strength in steel reinforced concrete (SRC) columns after fire exposure. Fire Technol. 53, 917–945. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10694-016-0610-6( (2017).

Wang, X. et al. Shear transfer mechanism of perforated web connection for concrete encased steel structures. Eng. Struct. 252, 113418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2021.113418 (2022).

Lin, Y. et al. Bond-slip properties and constitutive model of corroded H-shaped steel and concrete after freeze–thaw cycles. Structures 64, 106628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2024.106628 (2024).

Bai, L. et al. Experimental study on the bond behavior between H-shaped steel and engineered cementitious composites. Constr Build. Mater 196, 214–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.11.117 (2019).

Ju, Y., Shen, T. & Wang, D. Bonding behavior between reactive powder concrete and normal strength concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 242, 118024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.118024 (2020).

Majdi, Y., Hsu, C. T. T. & Punurai, S. Local bond–slip behavior between cold-formed metal and concrete. Eng. Struct. 69, 271–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2014.03.025 (2014).

Zhang, L. et al. Axial compressive behavior of steel-reinforced reactive powder concrete short columns. Structures 46, 433–444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2022.10.073 (2022).

Berthet, J. F., Yurtdas, I. & Delmas, Y. Evaluation of the adhesion resistance between steel and concrete by push out test. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 31, 75–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijadhadh.2010.11.004 (2011).

Liu, C. et al. Experimental study on bond slip behavior between section steel and RAC in SRRC structures. Constr. Build. Mater. 175, 104–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.04.120 (2018).

Azad, A., Sheikh, M. N. & Hai, F. I. A critical review of the mechanisms, factors, and performance of pervious concrete to remove contaminants from stormwater runoff. Water Res. 121101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2024.121101 (2024).

Zhang, Y. et al. Permeability of concrete and correlation with microstructure parameters determined by 1H NMR. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 4969680. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/4969680 (2020).

Xie, H. et al. Analytical model for two-dimensional contaminant transport in a cut-off wall and aquitard system. J. Hydrol. 643, 131951. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2024.131951 (2024).

Mostafazadeh, F., Kilanehei, F. & Hassanlourad, M. Experimental investigation of contaminant transport through saturated porous media under groundwater flow. Amirkabir J. Civ. Eng. 52, 23–26. https://doi.org/10.22060/ceej.2018.14655.5709 (2020).

Lee, J. M. et al. Numerical modeling of chloride transport in concrete under cyclic exposure to chloride. Materials 15, 5966. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15175966 (2022).

Speck, O. & Speck, T. An overview of bioinspired and biomimetic self-repairing materials. Biomimetics 4, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics4010026 (2019).

Wong, P. Y. et al. Advances in microbial self-healing concrete: A critical review of mechanisms, developments, and future directions. Sci. Total Environ. 947, 174553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.174553 (2024).

Algaifi, H. A. et al. Bio-inspired self-healing of concrete cracks using new B. pseudomycoides species. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 12, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2021.03.037 (2021).

Akbarpour, A. & Mahdikhani, M. Effects of natural zeolite and sulfate environment on mechanical properties and permeability of cement-bentonite cutoff wall. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 27, 1165–1178. https://doi.org/10.1080/19648189.2022.2075940 (2023).

Akbarpour, A., Mahdikhani, M. & Moayed, R. Z. Effects of natural zeolite and sulfate ions on the mechanical properties and microstructure of plastic concrete. Front Struct. Civ. Eng. 16(1), 86–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11709-021-0793-x (2022).

Akbarpour, A., Mahdikhani, M. & Ziaie Moayed, R. Mechanical behavior and permeability of plastic concrete containing natural zeolite under triaxial and uniaxial compression. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 34 (2), 04021453. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0004093 (2022).

Akbarpour, A., Volz, J. & Vemuganti, S. An experimental study incorporating carbon fiber composite bars and wraps for concrete performance and failure insight. J. Compos. Sci. 8(5), 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs8050174 (2024).

Xiao, Q. et al. Capillary water absorption performance and damage constitutive model of recycled concrete under freeze–thaw action. Constr. Build. Mater. 353, 129120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.129120 (2022).

Yan, F., Lin, Z. & Yang, M. Bond mechanism and bond strength of GFRP bars to concrete: A review. Compos. Part. B Eng. 98, 56–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2016.04.068 (2016).

Ma, Z., Zhu, F. & Ba, G. Effects of freeze-thaw damage on the bond behavior of concrete and enhancing measures. Constr. Build. Mater. 196, 375–385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.11.041 (2019).

Liu, K. et al. Bond behavior between deformed steel bars and recycled aggregate concrete after freeze–thaw cycles. Constr. Build. Mater. 232, 117236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.117236 (2020).

Yao, Z. et al. Experimental study on bond-slip behavior between shaped steel and concrete in SRC structures after freezing and thawing. J. Ningbo Univ. 36, 49–56 (2023). (in Chinese).

GB 175–2007. Common Portland Cement. National Standard of the People’s Republic of China, 3–4 (2007) (in Chinese).

GB/T50081-2019. Standard for test methods of physical and mechanical properties of concrete. National Standard People’s Repub. China (2019). (in Chinese).

GB/T 50082 – 2009. Standard for test method of long-term performance and durability of ordinary concrete. National Standard People’s Repub. China (2009). (in Chinese).

Xie, M. et al. Stochastic damage constitutive relationship of steel-reinforced concrete bond-slip. Shock Vib. 5553188. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/5553188 (2021).

Li, Y. L. et al. Damage characteristics and constitutive model of concrete under uniaxial compression after freeze–thaw damage. Constr. Build. Mater. 354, 128171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.128171 (2022).

Ji, X. & Song, Y. Mechanism of bond degradation between concrete and plain steel bar after freezing and thawing. J. Build. Struct. 32, 70–74 (2011). (in Chinese).

Luo, S. et al. Impact of freeze–thaw cycles on the long-term performance of concrete pavement and related improvement measures: A review. Materials 15, 4568. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15134568 (2022).

Jin, M. et al. Characterization of internal damage of concrete subjected to freeze-thaw cycles by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. Constr. Build. Mater. 152, 702–707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.07.039 (2017).

Shang, H., Zhao, T. & Cao, W. Bond behavior between steel bar and recycled aggregate concrete after freeze–thaw cycles. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol 118, 38–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2015.06.008(2015).

Fazel Mojtahedi, S. F. et al. Prediction of stress-dependent soil water retention using machine learning. Geotech Geol. Eng 42, 3939–3966. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10706-024-02767-8(2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors are very grateful to the anonymous reviewers and editors for their thoughtful review comments andsuggestions which have significantly improved this paper. This study was financially supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Sichuan Province under Grant No. 2022NSFSC0430.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.J.L., S.H.J.and S.Y.Z. wrote the main manuscript text and S.G. prepared all figures and tables. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, Y., Jiang, S., Zhong, S. et al. Bond behaviour between H-shaped steel and concrete after freeze-thaw cycles. Sci Rep 15, 29417 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14424-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14424-y