Abstract

Many biobanks store biological samples and use them for various analyses, including proteomics. Therefore, it is necessary to consider the denaturation of target proteins during long-term storage. We analyzed 16-year-old cryopreserved serum samples using the SomaScan platform, a novel proteomic assay, to determine whether adiponectin and resistin concentrations were consistent with those measured in our previous studies using a different platform. The results suggested that long-term cryopreserved serum samples could be used for future studies of at least adiponectin and resistin, which are closely related to the pathophysiology of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and other metabolic diseases. Therefore, 7,289 SomaScan-assayed circulating proteins were compared between 20 men and 20 women aged ≥ 50 to determine sex differences. In total, 20 serum proteins showed significant sex differences. Of these, proteins that showed a more than two-fold difference in concentration between sexes contained heterodimeric forms of gonadotropic proteins such as CGA|FSHB, CGA|CGB3|CGB7, and CGA|LHB, which are the biologically active forms of these hormones. The present study is the first to report the possibility of using long-term cryopreserved serum samples for the SomaScan assay, and the results show that the SomaScan assay may be useful for analyzing sex differences focusing on gonadotropic hormones.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Biological sex differences influence the signs and symptoms of age-related diseases in addition to inherent physical features. For example, the incidence of ischemic heart disease, the leading cause of death, increases rapidly in women after menopause1,2. In addition, women have higher rates of atypical angina symptoms (e.g., jaw pain and nausea) than men2,3,4and this potential diagnostic gap caused by sex differences may be contributing to increased mortality among women due to cardiovascular disease5. Similarly, there are biological sex differences in both the prevalence and symptom progression rate of Alzheimer’s disease6,7. Although the increasing life expectancy of women is considered a major reason for the high prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease, endocrinological changes associated with aging and lifestyle are a contributing factor8,9,10,11. Furthermore, there are several disparities in the aging trajectory between men and women12. Therefore, when considering sex differences in pathophysiology, it is imperative to understand how biological sex has an underlying effect at the foundation of disease onset during aging.

Almost all body cells are in contact with the blood, and many of them release some of their contents into the bloodstream through exocytosis or cell death (e.g., necrosis and apoptosis). Therefore, circulating proteins are recognized as potential biomarkers, and their fluctuations reflect physiological dynamics, aging, and organ dysfunction13. Proteomics has evolved dramatically in recent decades through the development of bioinformatics and innovations in measurement technology. To fundamentally understand biological systems, it is important to measure blood proteins over a dynamic range employing the greatest quantitative precision possible. In addition to liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry14,15,16affinity-based measurement technology is the most common method used to measure blood proteins, and it is becoming widely used. However, the SomaScan assay is a multiplex affinity-based proteomics platform that partially overcomes limitations, such as the dynamic range, of conventional methods using nucleic acid binders17,18. Indeed, a recent large-scale study using the SomaScan assay revealed novel age-related signatures and pathways that were not previously anticipated19 between men and women, and the results provided deeper insights into age-related fluctuations in plasma protein molecules caused by sex differences. However, this large-scale study consisted of Europeans and Americans19and the proteomic signature of biological sex differences in Asian ethnicities remains unclear. Therefore, we aimed to identify circulating protein concentrations in men and women of Asian ethnicities.

As blood samples are one of the easiest biological samples that can be collected, many biobanks store blood samples for a wide range of uses, including proteome analyses20,21. However, although these are important resources for bioinformatics, the storage period may potentially affect measurement results20,21,22and the effects of the storage period have not been adequately investigated using the SomaScan assay compared to those using conventional proteomics platforms. We previously measured serum adiponectin and plasma resistin concentrations through enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), a conventional immunoassay method23,24and measurements of these proteins using ELISA and SomaScan assay have been found to match with high accuracy25. These available ELISA-measured data prior to long-term cryopreservation prompted us to evaluate whether these stored serum samples could be reliably used with the SomaScan assay, a novel proteomics platform. Therefore, in addition to identifying circulating protein concentrations in men and women of Asian ethnicities, we also evaluated the use of long-term cryopreserved samples in the SomaScan assay.

Methods

Study design and participants

This cross-sectional observation study was designed as a part of the Kita-Nagoya Genomic Epidemiology (KING) study [ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00262691]23,24,26,27. The candidates were 1,876 individuals (887 men and 989 women) who participated in the KING study in 2007 and whose circulating adiponectin and resistin concentrations were measured in our previous studies23,24 using a latex turbidometric immunoassay (Otsuka Pharmaceutical Corporation, Osaka, Japan)23 and ELISA kit (LINCO Research, St Charles, MS, USA)24respectively. We matched men and women by age completely, and a total of 40 Japanese participants (20 men and 20 women) were eventually selected as the study participants. All 40 participants were ≥ 50 years old, and the mean age (standard deviation [SD]) was 64.9 (6.4) years old.

All serum samples used in this study had been stored at -80℃ since centrifuging whole blood from the KING study participants in 2007 (approximately 16-years). These whole blood samples were collected from the veins of participants who had fasted overnight. In the present study, the stored serum samples of the selected 40 participants were used for proteome analysis. As noted above, those serum samples were thawed and refrozen only once for adiponectin measurement.

Serum proteomics measurements

We used the SomaScan Discovery platform V4.1 (SomaLogic Inc., Boulder, CO, USA), which is based on slow off-rate modified single-stranded DNA aptamers (SOMAmers) binding to specific target proteins. SOMAmers exhibit high specificity and affinity for proteins and minimize nonspecific binding interactions because of their slow dissociation rates. Previous studies have reported high assay reproducibility and low technical variability with the SomaScan assay18,28. The abundance of each protein was derived from the relative fluorescence units (RFU) detected from each fluorescent dye. All serum samples were analyzed using the same version of the SomaScan assay and processed in a single batch to ensure consistency and to minimize potential batch effects. To account for sample-specific variability and distributional differences, proteomic data were normalized using adaptive normalization by maximum likelihood.

Statistical analysis

All statistical calculations were performed using R software (ver. 4.3.2, http://www.r-project.org/). During pre-processing, all RFU values of serum proteins were log2-transformed to approximate a normal distribution, and biological sex data were converted to a binary dummy variable (man: 1, woman: 0). The age-adjusted mean difference of log2 RFU values in serum protein between men and women was represented by the logarithm of fold change (FC = men/women).

Initially, we checked the quality of the 16-year cryopreserved samples using circulating protein data from the SomaScan assay and from our previous studies reporting serum adiponectin and plasma resistin concentrations23,24. Specifically, we evaluated the sample stability by comparing the concentrations of two proteins—adiponectin (measured by ELISA in serum) and resistin (measured by ELISA in plasma)—originally quantified from peripheral blood collected from the same individuals, with those measured 16 years later using SomaScan. Importantly, the blood samples themselves were identical; only the storage duration and measurement methods differed. We calculated Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients to evaluate the correlation between SomaScan assay data in 2023 and those from previous immunoassay measurements.

We then performed a multiple linear regression analysis to assess age-adjusted sex differences in serum protein concentrations measured by the SomaScan assay. This linear regression model included each log2 RFU value of serum protein as a dependent variable (Y), and biological sex and age as independent variables (X). P-values were adjusted using the Benjamini–Hochberg method29setting the significance threshold at a false discovery rate (FDR) = 0.05. We also evaluated the association between age and sex-differential serum protein concentrations detected by the abovementioned analysis. For each group of men and women, a simple linear regression analysis was performed with each log2 RFU value as Y and age as X, to assess whether the serum protein concentrations changed with age as a continuous variable at the significance level (α) = 0.05.

Results

Sample quality evaluation: Correlation between SomaScan assay and previous measurements of adiponectin and resistin

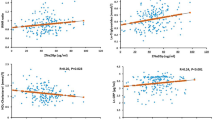

The SomaScan assay was conducted according to the standardized quality control processes (e.g., calibration and normalization) of SomaLogic Inc., with the remaining 7,596 measured proteins. Of these, 307 proteins not of human origin were not included in our analysis, and a total of 7,289 protein data points were included. Previous immunoassay data were combined with the SomaScan assay dataset, and the correlation between the previous immunoassays of adiponectin and resistin and the SomaScan assay measurements was obtained (Fig. 1). Serum concentrations of adiponectin in the same individuals at different measurement time points and assay methods were highly correlated (rs = 0.920, p = 5.38 × 10− 17). Despite the differences between the serum and plasma samples, the serum resistin and plasma resistin measurements using the SomaScan assay and ELISA were also highly correlated (rs = 0.713, p = 2.43 × 10− 7).

(a) Correlation between serum adiponectin concentrations measured by the SomaScan assay and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; Spearman’s correlation coefficient [rs] = 0.920, p = 5.38 × 10− 17). (b) Correlation between serum resistin concentrations measured by the SomaScan assay and plasma resistin concentration measured by ELISA (rs = 0.713, p = 2.43 × 10− 7).

Sex differences in serum protein concentrations

In the age-adjusted linear regression models, we evaluated the sex differences in serum protein concentrations (see Additional file 1 for details), and created volcano and MA plots of the results (Fig. 2). We found 20 serum proteins with significant sex differences (FDR < 0.05): nine of these were higher in men, and 11 were higher in women (Fig. 2a). These significant serum proteins were not at extremely high or low concentration ranges compared to all serum proteins (Fig. 2b). Of the significant serum proteins, the top three with the greatest sex differences were heterodimers: glycoprotein hormone α chain/follitropin subunit β (CGA|FSHB), glycoprotein hormone α chain/choriogonadotropin subunit β3/choriogonadotropin subunit β7 (CGA|CGB3|CGB7), and glycoprotein hormone α chain/lutropin subunit β (CGA|LHB). The serum concentrations of this gonadotropic hormone were more than twofold higher in women than in men (log2 (FC) < -1.0, Table 1). However, the RFU measurements of each β subunit of gonadotropic hormone did not differ between sexes (Table 1) when SOMAmer, which can recognize only the β subunit, was used.

(a) Volcano plot differentiating serum protein concentrations between men and women. Blue and red dots represent concentrations significantly higher in men and women, respectively. The horizontal green line indicates p-value = 0.05. (b) MA plot illustrating the association between serum protein concentrations and sex. Serum protein concentrations and sex represent the logarithm of fold change and the mean logarithm of relative fluorescence units.

However, sex differences in serum concentrations of the nine proteins with higher serum concentrations in men than in women were all less than two-fold (Table 1); the top three serum proteins with higher concentrations in men were β-defensin 104 (DEFB104A), matrix metalloproteinase-3/stromelysin-1 (MMP3), and prostate-specific antigen/kallikrein-related peptidase 3 (PSA/KLK3).

In each male and female group, the 11 and nine serum proteins with sex differences were evaluated to determine whether these were associated with age (Table 2). No serum protein concentration with a significant sex difference was associated with age, except neurotrimin (NTM, p = 0.039) and V-set immunoglobulin domain-containing protein 4 (VSIG4, p = 0.020).

Discussion

The present study investigated the possibility of using long-term cryopreserved serum samples with proteomics techniques and sex differences in circulating proteins in East Asians using their long-term cryopreserved samples. In the sample quality evaluation, we used ELISA-measured concentrations of adiponectin and resistin, both of which have been previously reported to be associated with their respective gene polymorphisms23,24. The serum concentration of adiponectin measured previously23 was almost identical to that measured by the SomaScan assay in the present study (rs = 0.920, p = 5.38 × 10− 17). In the evaluation of resistin measurements, a certain degree of correlation was confirmed between previous measurements24 and those using the SomaScan assay, although the correlation was not as high as that observed with adiponectin. One reason for the difference in this correlation is that resistin measurements were conducted using plasma samples in previous studies, whereas adiponectin measurements were made using serum samples. Given the different protein signatures of plasma and serum20it is possible that our long-term cryopreserved samples experienced minimal degradation and retained the potential to analyze their partial proteomic information. Our study presents evidence that long-term cryopreserved serum samples can at least be used in future studies of adiponectin, which is closely related to the pathophysiology of diabetes30cardiovascular disease31other metabolic diseases32.

Considering these results, a proteome analysis was performed using the long-term stored cryopreservation samples of the same 40 elderly Japanese participants, to evaluate sex differences in the serum protein concentrations. In women, serum concentrations of CGA|FSHB, CGA|CGB3|CGB7, and CGA|LHB (i.e., gonadotropic hormones) were more than two-fold higher than those of men, and these results were consistent with those of a large study involving other ethnic groups19. While menopausal status was not directly assessed in this study, the observed sex differences in gonadotropin levels may reflect expected physiological differences in older adults. Notably, regression analyses did not show significant age-related variation within this age composition, which aligns with prior literature suggesting that gonadotropin concentrations stabilize several years after menopause33,34,35,36. However, as menopausal status was not documented, these interpretations should be made with caution. Furthermore, the SomaScan platform measures heterodimeric forms of gonadotropins such as CGA|FSHB, CGA|CGB3|CGB7, and CGA|LHB, which represent the biologically active forms of these hormones. This contrasts with assays that detect individual subunits and may not reflect functional hormone concentrations. The ability to quantify intact heterodimers enhances the interpretability of proteomic data and highlights the utility of SomaScan for investigating physiologically relevant hormonal patterns. However, there were no differences between the serum concentrations of subunits of these heterodimer gonadotropins between men and women using the SomaScan assay. Therefore, the feasibility of measuring solely subunits in long-term cryopreserved serum samples using the SomaScan assay requires further investigation. In addition, our study showed that serum levels of DEFB104A, MMP3, and PSA/KLK3 were higher in males than in females. According to the Human Protein Atlas (Version: 24.0; https://www.proteinatlas.org/), both DEFB104A and PSA/KLK3 are highly expressed in male-specific organs such as the epididymis and prostate. Additionally, higher serum concentrations of MMP-3 have been reported in men than in women in healthy populations37which is consistent with our present findings.

Furthermore, we identified NTM and VSIG4 as circulating proteins whose serum concentrations increase with age in men and women, respectively. NTM is a cell adhesion molecule closely related to neural connectivity and neurite outgrowth, and it is also expressed at high levels primarily in the olfactory bulb, neural retina, dorsal root ganglia, and spinal cord38. Recent genome-wide association studies have reported that four SNPs located within intron 1 of the NTM gene are associated with late-onset Alzheimer’s disease39. VSIG4 is highly expressed on tissue resting macrophages, the giant red pulp progenitor cells derived from fetal liver Kupffer cells, and is closely related to opsonophagocytosis of pathogens and the subsequent inflammatory response process40,41,42. VSIG4 is associated with insulin resistance and the epithelial-mesenchymal transition of kidney tubular cells under hyperglycemia43,44. Although our proteomic study was small-scale, it provided important insights into differences between the sexes with age in East Asian populations, particularly regarding neurological and immunological aspects.

However, our study has several limitations: first, the sample quality evaluation was performed only for resistin and adiponectin. Thus, we should be cautious when evaluating other serum proteins outside the nanogram to microgram per milliliter order range of the easily catabolized magnitude, especially those present in trace amounts. Second, the effects of remelting and refreezing were not considered in the possibility of using the long-term cryopreserved samples presented in this study. To quantitatively assess time-dependent serum protein degradation and the impact of repeated freeze–thaw cycles, future longitudinal studies using samples stored for varying durations are necessary. Third, in the exploratory analyses assessing the relationship between age and serum protein levels that showed sex differences, statistical significance was evaluated based only on nominal p-values without adjustment for multiple testing. As such, these results should be interpreted with caution and cannot support definitive conclusions. Finally, the sample size of this study was relatively small, and there was no validation dataset. To test the robustness of our results, it is necessary to apply them to another long-term sample from a population different from that in the present study. Consistency with another assay method also needs to be confirmed in the future.

Conclusions

Despite the limitations, the present study is the first to report the possibility of using long-term cryopreserved serum samples in the SomaScan assay, a novel proteomics platform. Many biobanks have stored numerous biospecimens; therefore, our results could contribute to the successful utilization of their sample properties. In addition, we identified heterodimer gonadotropic hormones as protein markers that were present at more than twice the serum concentration in elderly Japanese women compared with that in elderly Japanese men.

Data availability

Availability of Data and Materials: All data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.

Change history

12 December 2025

The original online version of this Article was revised: The Equal contribution statement for Authors Ruriha Beppo and Yuki Ohashi was missing. The correct information now accompanies the original Article.

References

Gordon, T., Kannel, W. B., Hjortland, M. C. & McNamara, P. M. Menopause and coronary heart disease. The Framingham study. Ann. Intern. Med. 89, 157–161. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-89-2-157 (1978).

DeVon, H. A. & Zerwic, J. J. Symptoms of acute coronary syndromes: Are there gender differences? A review of the literature. Heart Lung. 31, 235–245. https://doi.org/10.1067/mhl.2002.126105 (2002).

Dey, S. et al. Sex-related differences in the presentation, treatment and outcomes among patients with acute coronary syndromes: the global registry of acute coronary events. Heart 95, 20–26. https://doi.org/10.1136/hrt.2007.138537 (2009).

Eastwood, J. A. et al. Anginal symptoms, coronary artery disease, and adverse outcomes in black and white women: The NHLBI-sponsored women’s ischemia syndrome evaluation (WISE) study. J. Womens Health (Larchmt). 22, 724–732. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2012.4031 (2013).

Bairey Merz, C. N. Sex, death, and the diagnosis gap. Circulation 130, 740–742. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.011800 (2014).

Fisher, D. W., Bennett, D. A. & Dong, H. Sexual dimorphism in predisposition to alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 70, 308–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2018.04.004 (2018).

Barth, C., Crestol, A., de Lange, A. G. & Galea, L. A. M. Sex steroids and the female brain across the lifespan: insights into risk of depression and alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 11, 926–941. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(23)00224-3 (2023).

Morrison, J. H., Brinton, R. D., Schmidt, P. J. & Gore, A. C. Estrogen, menopause, and the aging brain: how basic neuroscience can inform hormone therapy in women. J. Neurosci. 26, 10332–10348. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3369-06.2006 (2006).

Rocca, W. A., Grossardt, B. R. & Shuster, L. T. Oophorectomy, menopause, Estrogen treatment, and cognitive aging: Clinical evidence for a window of opportunity. Brain Res. 1379, 188–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2010.10.031 (2011).

Dhana, K. et al. Healthy lifestyle and life expectancy with and without alzheimer’s dementia: Population based cohort study. BMJ 377, e068390. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2021-068390 (2022).

Arenaza-Urquijo, E. M. et al. Sex and gender differences in cognitive resilience to aging and alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 20, 5695–5719. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.13844 (2024).

Ostan, R. et al. Gender, aging and longevity in humans: an update of an intriguing/neglected scenario paving the way to a gender-specific medicine. Clin. Sci. (Lond). 130, 1711–1725. https://doi.org/10.1042/CS20160004 (2016).

Oh, H. S. et al. Organ aging signatures in the plasma proteome track health and disease. Nature 624, 164–172. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06802-1 (2023).

Ichibangase, T. & Imai, K. Development and application of FD-LC-MS/MS proteomics analysis revealing protein expression and biochemical events in tissues and cells. Yakugaku Zasshi. 135, 197–203. https://doi.org/10.1248/yakushi.14-00213-2 (2015).

Shibata, H. et al. A Non-targeted proteomics newborn screening platform for inborn errors of immunity. J. Clin. Immunol.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10875-024-01821-7 (2024).

Kato, C. et al. Proteomic insights into extracellular vesicles in ALS for therapeutic potential of ropinirole and biomarker discovery. Inflamm. Regen. 44, 32. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41232-024-00346-1 (2024).

Gold, L., Walker, J. J., Wilcox, S. K. & Williams, S. Advances in human proteomics at high scale with the SOMAscan proteomics platform. N Biotechnol. 29, 543–549. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbt.2011.11.016 (2012).

Candia, J. et al. Assessment of variability in the SOMAscan assay. Sci. Rep. 7, 14248. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-14755-5 (2017).

Lehallier, B. et al. Undulating changes in human plasma proteome profiles across the lifespan. Nat. Med. 25, 1843–1850. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-019-0673-2 (2019).

Hsieh, S. Y., Chen, R. K., Pan, Y. H. & Lee, H. L. Systematical evaluation of the effects of sample collection procedures on low-molecular-weight serum/plasma proteome profiling. Proteomics 6, 3189–3198. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmic.200500535 (2006).

Luque-Garcia, J. L. & Neubert, T. A. Sample Preparation for serum/plasma profiling and biomarker identification by mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A. 1153, 259–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chroma.2006.11.054 (2007).

Pieragostino, D. et al. Pre-analytical factors in clinical proteomics investigations: Impact of ex vivo protein modifications for multiple sclerosis biomarker discovery. J. Proteom. 73, 579–592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jprot.2009.07.014 (2010).

Tanimura, D. et al. Relation of a common variant of the adiponectin gene to serum adiponectin concentration and metabolic traits in an aged Japanese population. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 19, 262–269. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2010.201 (2011).

Asano, H. et al. Plasma resistin concentration determined by common variants in the resistin gene and associated with metabolic traits in an aged Japanese population. Diabetologia 53, 234–246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-009-1517-2 (2010).

Rooney, M. R. et al. Comparison of proteomic measurements across platforms in the atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) study. Clin. Chem. 69, 68–79. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinchem/hvac186 (2023).

Nakatochi, M. et al. The ratio of adiponectin to homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance is a powerful index of each component of metabolic syndrome in an aged Japanese population: results from the KING study. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 92, e61–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2011.02.029 (2011).

Nakatochi, M. et al. Epigenome-wide association study suggests that SNPs in the promoter region of RETN influence plasma resistin level via effects on DNA methylation at neighbouring sites. Diabetologia 58, 2781–2790. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-015-3763-9 (2015).

Kim, C. H. et al. Stability and reproducibility of proteomic profiles measured with an aptamer-based platform. Sci. Rep. 8, 8382. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-26640-w (2018).

Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery Rate - a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R Stat. Soc. B. 57, 289–300. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x (1995).

Fasshauer, M., Bluher, M. & Stumvoll, M. Adipokines in gestational diabetes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2, 488–499. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70176-1 (2014).

Peng, J., Chen, Q. & Wu, C. The role of adiponectin in cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 64, 107514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carpath.2022.107514 (2023).

Straub, L. G. & Scherer, P. E. Metabolic messengers: Adiponectin. Nat. Metab. 1, 334–339. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42255-019-0041-z (2019).

Weiss, G., Skurnick, J. H., Goldsmith, L. T., Santoro, N. F. & Park, S. J. Menopause and hypothalamic-pituitary sensitivity to Estrogen. JAMA 292, 2991–2996. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.292.24.2991 (2004).

Sowers, M. R. et al. Follicle stimulating hormone and its rate of change in defining menopause transition stages. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 93, 3958–3964. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2008-0482 (2008).

Randolph, J. F. Jr. et al. Change in follicle-stimulating hormone and estradiol across the menopausal transition: effect of age at the final menstrual period. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 96, 746–754. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2010-1746 (2011).

Santoro, N., Roeca, C., Peters, B. A. & Neal-Perry, G. The menopause transition: Signs, symptoms, and management options. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 106, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgaa764 (2021).

Ribbens, C. et al. Increased matrix metalloproteinase-3 serum levels in rheumatic diseases: Relationship with synovitis and steroid treatment. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 61, 161–166. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.61.2.161 (2002).

Struyk, A. F. et al. Cloning of neurotrimin defines a new subfamily of differentially expressed neural cell adhesion molecules. J. Neurosci. 15, 2141–2156. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-03-02141.1995 (1995).

Liu, F. et al. A genomewide screen for late-onset alzheimer disease in a genetically isolated Dutch population. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 81, 17–31. https://doi.org/10.1086/518720 (2007).

Langnaese, K., Colleaux, L., Kloos, D. U., Fontes, M. & Wieacker, P. Cloning of Z39Ig, a novel gene with immunoglobulin-like domains located on human chromosome X. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1492, 522–525. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0167-4781(00)00131-7 (2000).

van Lookeren Campagne, M., Wiesmann, C. & Brown, E. J. Macrophage complement receptors and pathogen clearance. Cell. Microbiol. 9, 2095–2102. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00981.x (2007).

Li, Y. et al. Therapeutic modulation of V set and Ig domain-containing 4 (VSIG4) signaling in immune and inflammatory diseases. Cytotherapy 25, 561–572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcyt.2022.12.004 (2023).

Luo, Z. et al. CRIg(+) macrophages prevent gut microbial DNA-Containing extracellular Vesicle-Induced tissue inflammation and insulin resistance. Gastroenterology 160, 863–874. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2020.10.042 (2021).

Gong, E. Y. et al. VSIG4 induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition of renal tubular cells under high-glucose conditions. Life (Basel). https://doi.org/10.3390/life10120354 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank all study participants.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, including Grant-in-Aid for Transformative Research Areas (22H04923), Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research(B) (21H03206, 23K24608, 24K02690), and Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research(C) (20K10514), by grants from Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) under Grant Numbers JP21wm0425013 and JP24wm0625301, and by grants from center for research, education, and development for healthcare life design (C-REX), Nagoya (or Gifu) University, Japan. Suzuken Memorial Foundation and the Gout and Uric Acid Foundation of Japan (grant number: #23–081) also supported this study financially. The funders played no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, reporting, or the decision to submit for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MN, KY, FK, TK, MK, TM, MY, and SI contributed to the conception or design of the study. RB, YO, and MN performed data analysis and interpreted the results. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and agrees to be personally accountable for the individual’s contributions and to ensure that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work, even one in which the author was not directly involved, are appropriately investigated and resolved, including with documentation in the literature if appropriate.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and its protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Jichi Medical University (approval #23–097) and Nagoya University, School of Medicine (approval #2020-0047). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants at the beginning of the KING study, and participants could discontinue participation at any point during the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Beppo, R., Ohashi, Y., Yamamoto, K. et al. Evaluation of serum samples in long cryopreservation for SomaScan proteomics and sex differences in elderly Japanese adults. Sci Rep 15, 29849 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14464-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14464-4