Abstract

Low back injuries are globally prevalent among construction workers, leading to significant economic burdens. Despite various intervention strategies, their effectiveness remains uncertain. This study evaluates a lightweight active soft back exosuit (SV Exosuit) against a passive rigid exosuit (IX BACK) to assess muscle activity and usability. Fifteen healthy participants performed bending and lifting tasks under three conditions: no exosuit, with SV Exosuit, and with IX BACK. Electromyographic (EMG) signals from back extensors were collected, and subjective feedback was obtained using the NASA task load index (NASA-TLX). Results showed that the active exosuit significantly reduced mean and peak EMG levels, while the passive exoskeleton exhibited modest reductions, particularly during unloaded tasks. EMG pattern analysis indicated peak activity occurring within 30–40% of the motion cycle, with IX BACK causing delays in bending without load due to resistance. Overall, both devices alleviated muscle strain, with SV Exosuit providing superior support during loaded tasks. The findings suggest that SV Exosuit’s lightweight and effective design make it a preferable option for construction tasks, highlighting the need for further research on its application in real-world settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Construction workers typically perform prolonged heavy-labored tasks, leading to a high incidence of low back injuries1. Safety records indicate that low back injuries are reported in 12% to 56% of construction workers2,3. The prevalence of low back injuries in the construction industry imposes a significant financial burden on both workers and employers, encompassing direct expenses for treating injuries and indirect costs due to early retirement and absenteeism of impaired workers4. For example, Carregaro et al.5 reported that Brazil spends approximately USD $500 million for annual low back pain (LBP) treatment, and Alonso-García and Sarría-Santamera6 presented that Spain costs over EUR €6,500 million per year for work losses by LBP. However, mitigating low back injuries in the construction industry remains challenging, as awkward working postures and excessive physical demand are inevitable due to the reliance on manual handling and the sophisticated working environment.

Biomechanical studies demonstrate that improper lifting techniques amplify lumbar spine bending moments by approximately 75% compared to proper squat lifting techniques7. This mechanical overload significantly increases the probability of exceeding critical tissue tolerance thresholds, thereby elevating injury risk8. Consequently, in response, industry practitioners have implemented various intervention strategies, such as using cameras and sensors to track and recognize risky activities9,10 and training workers to adopt postures that minimize low back strain10. Nevertheless, the effectiveness of these strategies remains uncertain. For instance, on construction sites, the prevalent clutter, occlusions, and changing lighting conditions can affect the ability of the camera to recognize the workers’ activities11,12. For wearable sensors, previous studies suggested that the complex and awkward postures in the construction activities limit sensor attachment, making the optimal number and location of sensors for activity recognition not applicable13,14. Additionally, safety training has shown limited impact on workers’ safety self-efficacies and outcome expectancies15,16.

Recently, the use of back exosuits, or known as back exoskeletons or back-support exoskeletons (BSEs), has gained attention as an effective solution to prevent low back injuries. Exoskeleton, also known as exoskeleton suit or exosuit, is a type of wearable robot that provides support or protection to the wearer during activities. These devices can be classified as active or passive according to the types of actuators used to provide assistive torques or forces. Passive back exosuits employ passive actuators, such as springs located at hips or elastic bands on the back, storing energy during trunk bending and releasing it to provide supportive torque/force during lifting. In contrast, active back exosuits generate supportive force through actuators powered by external sources, such as batteries. The types of active actuators vary based on the source of power generation source, including electric motors, hydraulic actuators and pneumatic actuators. These actuators are controlled by a control system, enabling them to provide force assistance when needed without impeding regular motions17. As supported by external power generating actuators, active back exosuits commonly can provide higher assistive forces than passive suits. For instance, active back exosuits reduce back muscle loads by 25% to 41%, while passive suits reduce by 16–18%18,19,20. However, active devices are usually limited by their heavy weights21. Exoskeletons can also be classified as rigid and soft based on the design for force transmission. Rigid designs contain stiff components that are heavier and bulkier, making the designs harder to don and usually constrain joint movements22,23. Soft designs usually employ textile-based soft materials, and the designs present lighter and easier to don22,23.

Back exosuits can also be categorized based on the specific supporting body region, and the examples include ShoulderX (SUITX by Ottobock, Emeryville, California, United States) for shoulder support, Laevo Flex (Laevo Exoskeletons, Delft, Netherlands) and StreamEXO24 for low back support, HAL (Cyberdyne Inc., Ibaraki, Japan) for lower limb support, and XO (Sarcos Corporation, Salt Lake City, United States) for whole-body support. Specifically, back exosuits help reduce low back loading during heavy lifting tasks by applying external force to the trunk, with studies showing a reduction of 10–40% in back muscle loads18,25, and wearing these exosuits could potentially reduce the risk of low back disorders by approximately 20%26.

Despite the potential benefits of back exosuits for industrial workers including construction workers, several critical limitations were caused by the supporting strategy, and the corresponding design may hinder wider applications in practice. One limitation is that as the back load is transferred to other body parts by the exosuits, the chest, upper legs, and arms regions are usually reported to perceive increased discomfort27. Also, many passive back exosuits transfer forces from actuators to the trunk using rigid mechanical frames, which may hinder natural body motions of wearers28, and this hindrance potentially increases heart rate and skin temperature during performing tasks29. Though active back exosuits generally better adapt the wearer and provide greater assistive forces than the passive19, they usually rely on the batteries for power supply, the motors for the generation of the assistive force, and the rigid mechanical components and gears to transfer the assistive force30. These make the active back exosuits much heavier than passive. For example, passive back exosuits like BackX (SuitX by Ottobock SE and Co. KGaA, Duderstadt, Germany) and Laevo v2.56 (Laevo Exoskeletons, Delft, Netherlands) weigh 3.0 kg, while active back exosuits like Cray X (German Bionic, Augsburg, Germany) and XoTrunk31 respectively reaches 7.0 kg and 8.0 kg19,32. Further, the high cost of active exosuits contributes to low adoption rates in practice. Considering these limitations, rigid active exoskeletons are impractical for occupational environments due to excessive mass and bulk21. Soft passive variants provide much lower support than rigid passive, making the torque generation inadequate for construction lifting demands26,33. Rigid passive and soft active designs are viable exoskeleton solutions for construction settings.

To enable widespread adoption of back exosuits in construction environments, developing lightweight, flexible designs with active support capabilities is critical, and developing a soft active exosuit is a way to achieve these goals. A promising approach for soft active exosuit involves pneumatic artificial muscles (PAMs), which offer advantages for wearable assistive devices. For example, PAMs showed satisfactory compliance to the body structure and the user’s activity while provided sufficient force generation capacity ranging from 100 to 800 N in a designed way34. Additionally, PAMs presented relatively high power-to-weight ratio that reaches 400 to 1000 W/kg35. The authors of the current study previously designed and developed a lightweight active soft back exosuit utilizing eight PAMs that are positioned parallel to the center of the back and connected to the shoulders and hips via straps21. Each PAM can produce a contraction force of up to 116 N, responding to the user’s trunk movement. The device weighs only 1.91 kg, and the preliminary evaluations indicate that this new soft back exosuit can reduce back extensor muscle activations by 13.0–37.0%21.

While the developed soft active back exosuit may have comparative advantages over existing rigid passive exosuits due to its innovative design and active support mechanisms, it is necessary to evaluate its performance and usability by comparing it with existing passive exosuits in a controlled setting. Previous studies have employed different methods to evaluate and compare the performances of back exoskeletons. For example, Imamura, et al.36, Bianco et al.37 and Heydari et al.38 evaluated the exoskeletons through comparing the effects on the low back joints and muscles by biomechanical simulations. Yet simulation models are commonly simplified with reduced muscle groups and sometimes with neglected limb motions37, reducing the accuracy of the models. Moreover, the precision of the models remain hard to verify, as the joint and muscle forces are internal forces and are difficult to directly measure. Van Harmelen et al.39 and Imamura et al.36 examined the exoskeletons through measuring the supportive torque or force provided. However, provided support is dependent on the wearer’s build40, as torque is the product of the force vector and the position vector applied by the force. Bianco et al.37 and Schmalz et al.41 investigated the devices by measuring the variations of the metabolic cost, but metabolic cost can be affected by many other factors such as task intensity, health condition, impedance of non-portable equipment, and food and nicotine intake42,43. Heydari et al.38, Alemi et al.44, Schmalz et al.41, and Lei et al.21 assessed the exoskeletons by comparing the variation of the electromyographic (EMG) signals of the muscles. Though EMG could not represent the applied muscle force, this signal can inform the activation level of the muscle45,46, and it is commonly used for exoskeleton validation47. Many studies also employ subjective feedback, surveys, questionnaires, and interviews as supplementary evaluation of exoskeleton21,48,49,50.

While existing research has extensively validated passive exoskeletons in isolation, and multiple review studies have attempted comparative performance analyses, the inconsistent evaluation conditions in experimental methodologies, particularly in testing protocols and lifting tasks, impede meaningful cross-model comparisons17,47,50,51,52,53,54,55,56. For illustration, Wehner57 had subjects lift objects weighing 10 lb and 30 lb using a squat lifting method, while Imamura, et al.36 required subjects to bend forward while holding a 6 kg weight. Heydari et al.38 had subjects maintain their trunks at three bending angles (0°, 30°, and 60°) with varying loads (0 kg, 5 kg, and 15 kg). In terms of muscle activity evaluation, different studies collected EMG data from various muscle groups. Heydari et al.38 collected the EMG from lumbar and thoracic erector spinae and latissimus dorsi, while Alemi58 collected from iliocostalis lumborum and longissimus thoracis. The inconsistency in the experimental conditions highlights the need for a direct comparison of the developed exosuit with existing passive models for further validation to determine relative advantages.

Given that soft active back exosuit is relatively novel in the construction domain, practitioners may encounter challenges in selecting the appropriate type of back exosuit compared to the traditional passive and rigid back exoskeletons. This difficulty arises from their unfamiliarity with these products and budget constraints limiting their ability to experiment, and the existing studies provide limited information for their refence. From a practitioner’s perspective, comparing the functional performance and usability of the back exosuits would facilitate better decision making regarding the selection of appropriate exoskeleton types for construction workers. Additionally, this comparison would provide valuable insights into further improving the design of the back exosuits. While some prior studies have compared back exoskeletons within a general industrial context19,59,60, it is essential to recognize that construction sites are typically complex and dynamic61. Additionally, LBP is the most prevalent work-related musculoskeletal disorder among construction workers2,3. Therefore, back exoskeletons designed for manual repetitive lifting tasks in construction settings warrant separate examination to accurately evaluate their performance and implications. Moreover, as elaborated in the previous paragraph, though numerous back exoskeletons have undergone individual evaluation21,47,53,54, the heterogeneity of experimental conditions across studies precludes meaningful cross-study comparisons. Furthermore, though conventional types of back exosuit such as rigid passive and rigid active have been compared in some studies19,32, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, no prior work has directly compared soft active exosuits against rigid passive designs. Consequently, a controlled, side-by-side comparison between the innovative soft active and a conventional rigid passive back exosuit under identical construction-relevant conditions is therefore necessary to objectively quantify performance difference and provide evidence-based selection guidelines for practitioners. The findings offer valuable reference information for industrial practitioners, enabling them to make informed decisions regarding the selection of back exosuit types and contributing to the future design and development of these technologies.

Building on this foundation, this study aims to employ empirical experimentation to conduct a comparative evaluation of the soft active back exosuit previously developed by Lei et al.21, SV Exosuit, against an existing commercially available rigid passive back exosuit, IX BACK (Ottobock SE & Co., Duderstadt, Germany), assessing both performance and usability metrics under controlled conditions. Based on the results, this study analyzes the comparative advantages of SV Exosuit over IX BACK, while also discussing the remaining challenges and ways to improve the design. According to the independent evaluations conducted by previous studies, it is claimed that both selected back exosuits significantly reduced back muscle activities during lifting tasks21,62,63, and SV Exosuit provided larger maximum supportive torque (about 54 Nm)21 than IX BACK (about 49 Nm)39. Based on these previous results, this study hypothesized that when performing identical tasks, both back exosuits significantly reduce back muscle activities. This study also hypothesized that SV Exosuit reduces back muscle activities more pronouncedly than IX BACK under identical conditions.

Methodology

Participants

A convenience sample of 15 healthy young participants (11 males and 4 females) were voluntarily recruited in this study, with a mean (standard deviation, SD) age, body mass, and height of 26.87 (4.12) years, 73.00 (13.06) kg, 175.00 (8.00) cm. The sample size was determined based on a-priori power analysis referencing the EMG dataset reported in a previous study21, indicating that fewer than 10 participants would provide a minimum statistical power of 0.8 with a significance level α of 0.05. Given that males constitute over 80% of the construction workforce64, our participant pool reflects this industry gender distribution, with male subjects comprising the study majority. Participants were not trained to perform labor-intensive work and were unfamiliar with any kind of back-support device. Selection criteria included: (a) no history of pathological low back pain, and (b) no injuries or disorders that could impact their ability to perform trunk lifting tasks. These criteria were set as the compared devices aim to prevent low back injury rather than assist with rehabilitation, ensuring that any injuries or medical histories did not influence task performance or experimental results. This study was approved by the Departmental Research Committee (HSESC) of The Hong Kong Polytechnic University (HSESC reference number: HSEARS20231012009) and was conducted in compliance with the ethical standards and institutional guidelines. All participants provided written informed consent prior to experiments.

Compared back-support devices

This study compared two distinct back-support exosuits: SV Exosuit developed by our team and the IX BACK exosuit from SUITX by Ottobock. SV Exosuit is an active and soft back exosuit based on PAMs (Fig. 1a), and the details of this device were introduced in the previous section. The compressed gas supplied to the PAMs was provided at the maximum pressure of 0.9 MPa in this study.

SV Exosuit was previously designed and developed by the authors21. Eight PAMs are positioned parallel to the center of the back and connected to the shoulders and hips via straps. A portable air pump supplies compressed gas to inflate and contract the PAMs, mimicking muscle contraction and providing assistive forces during lifting. Each PAM can produce a contraction force of up to 116 N, responding to the user’s trunk movement data collected from a wearable inertial measurement unit (IMU). The IMU continuously monitors trunk flexion angles, while an embedded microcontroller implements real-time posture classification. When forward bending the upper body (i.e. the bending angle is over 60°), the control system activates pneumatic supply to the artificial muscles, inducing PAM contraction. When returning the upper body to upright posture (i.e. the bending angle is below 20°), the system vents compressed gas to facilitate PAM relaxation. The air pump and control system run on a replaceable battery that is estimated to last at least 8 h. The exosuit weighs 1.91 kg with dimension of 42 (height) × 20 (width) × 8 (depth) cm. The design has been further integrated the exosuit into a safety vest for the convenience of construction workers, replacing the air pump with a bottle of compressed CO2 for quicker response (Fig. 1a). To distinguish the updated design from the previous, here we refer to the updated design as SV (safety vest) Exosuit.

IX BACK is a passive and rigid back exosuit designed to support the back during lifting tasks. It comprises two shoulder straps, a chest pad, a waist strap, two thigh pads, two torque generators positioned adjacent to the hips, and two force transmission rods located at the back (Fig. 1b). When the wearer bends down, the weight of the trunk is transferred through the force transmission rods to the torque generators, where the torsional spring within the torque generator stores energy. When the wearer lifts up, this stored energy is released to compensate for the muscle force needed. As approximately half of construction jobs involve lifting objects weighing between 19.5 and 25.5 kg19,65, and the rate of LBP among workers performing these tasks (59–75%) is notably higher among those lifting lighter loads (12–48%)65, a back exosuit for construction workers is expected to support lifting at least 20 kg. Prior research has confirmed enhanced task performance and favorable user acceptance of IX BACK, making it suitable for dynamic construction environments involving about 20 kg loads33. Additionally, IX BACK provides relatively higher supportive torque than the commercial passive rigid back exosuits that are widely investigated26,39. The relatively higher support and prior wide validation justify IX BACK as a benchmark for this comparative assessment. The adjustable supportive torque of IX BACK was set to the high gear in this study. The weights and the dimensions of these two devices are presented in Table 1.

Experimental design

Before performing the tasks, the maximum voluntary contraction (MVC) of each back extensor was collected for EMG normalization. During the MVC trial, participants were positioned prone on a mat with counter-pressure applied at the upper back, pelvis, and ankles. From this position, they were instructed to extend their upper body against resistance with maximal effort66. A three-minute break was provided after the MVC trial to minimize the effect of muscle fatigue.

Repeated measures experimental design was used to evaluate the effects of SV Exosuit and IX BACK on lifting performance. Participants completed two sessions in alternate design, one session involved bending the trunk down without bending the knees, and the other session involved lifting the trunk up. Each session was performed without any load (0 kg) with 10 repetitions, as well as holding a 25 kg load (46 length × 34 width × 26 height cm) in hands with 10 repetitions. When lifting with the load, participants were required to raise it to the level of their knees (approximately raise 55 cm)67. Standardized postures and activities were implemented because the study objective necessitated controlled comparison of back exoskeleton effects on muscular activation patterns. A 25 kg load was selected to simulate typical construction lifting tasks, reflecting the common 19.5–25.5 kg weight range observed in practice (as mentioned in Section “Compared back-support devices”). Participants repeated the sessions across three conditions—without any assistive device (no exo), with SV Exosuit (with active exosuit), and with IX BACK (with passive exoskeleton). To minimize sequence effects, the condition sequence was randomized for each participant. A five-minute break was provided between each condition to minimize the effects of muscle fatigue68.

Data collection and analysis

Surface EMG (sEMG) signals were collected from the back extensors to evaluate their activity levels during the experimental tasks. EMG assessment of lumbar musculature serves as the primary outcome measure of the exoskeleton’s efficacy, given its established correlation with musculoskeletal injury risk during occupational exertion69,70,71,72. In this study, sEMG electrode pairs made of Ag/AgCl (SE-00-S/50, Ambu BlueSensor, Denmark) were attached to the skin surface of the back extensors (as shown in Fig. 2). The back extensors, specifically, longissimus erector spinae, were identified and electrodes were placed in accordance with SENIAM guidelines73. Specifically, surface electrodes were positioned 2-finger-width lateral to the L1 spinous process, aligned parallel to the muscle fiber orientation.

A built-in amplifier with a common mode rejection ratio (CMRR) over 100 dB and amplification of 800 with active band pass filter between 10 and 500 Hz was used to amplify the collected EMG signals. A data acquisition (DAQ) component (USB-6001, NATIONAL INSTRUMENTS CORP., Austin, Texas, USA) was employed to record the EMG signals, which was simultaneously read and stored through NI LabVIEW (LabVIEW 2021 (64-bit), NATIONAL INSTRUMENTS CORP., Austin, Texas, USA) at a sampling rate of 1 kHz. Given that the tasks in this study involved dynamic activities, the collected EMG data were normalized to reduce the inter-individual variability. The EMG signals were normalized to the percentage of the maximum EMG of each participant74 and presented as MVC%. The peak and mean EMG values were averaged across all participants for analysis.

To assess the subjective perception of task-related workload, this study employed NASA task load index (NASA-TLX) questionnaire that allows individual ratings for mental demand (MD), physical demand (PD), temporal demand (TD), performance (P, higher score for less successful), effort (E), and frustration (F)75. Participants filled out a NASA-TLX questionnaire to provide summary feedback on their task performance after completing each condition.

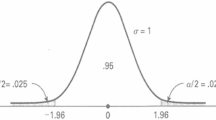

The collected EMG data were segmented according to bending and lifting motion phases, defined by kinematic event timing. Next, the data were summarized as the average mean EMG across all subjects during each session (either bend down or lift up), and the averages under different conditions were statistically compared. Similarly, the averages of the peak EMG were compared using the same method as the mean EMG. To further investigate EMG variation between different conditions, the collected EMG curves during the same session were normalized from a time frame to a cycle frame and grouped together to observe variations in EMG patterns. The subjective ratings for each item under different conditions were averaged and statistically compared to observe the relationship between subjective feedback and exosuit condition. For statistical comparisons, the normality of the collected data was first examined using Shapiro–Wilk normality test76. Paired comparisons were performed using Wilcoxon signed-rank test for non-normally distributed groups77, which included the means and peaks of EMG, and using paired t-test for normally distributed groups78, which included the items of subjective feedback. A Mann–Whitney U test was employed to conduct pairwise comparisons of anthropometric measurements and EMG outcomes between male and female participants79, enabling further investigation of gender-related differences. Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons was applied when appropriate78. The statistical analyses were performed in MATLAB (R2024a, MathWorks Inc., Natick, Massachusetts, USA) with a significance level α < 0.05.

Results

Performance evaluation by back muscle activity test

Figure 3a presents the average mean EMG of the back extensors across four sessions, namely bend down without load (0 kg), lift up without load (0 kg), bend down with load (25 kg), and lift up with load (25 kg), under the three conditions, which are no exo, with active exosuit, and with passive exoskeleton. The corresponding statistical results are shown in Table 2. Overall, with active exosuit, the mean EMG was observed to be significantly reduced during all sessions except for bend down, with the reduction rates ranging between 23.57% and 32.04%. With passive exoskeleton, the mean EMG was significantly reduced in the sessions with 25 kg load (17.11–33.81%). Although not significant, there was a trend toward decreased mean EMG in the lift-up session without load (14.17%). These results confirm the effectiveness of both exosuits to reduce mean back muscle activity when lifting and lowering objects weighing up to 25 kg.

The reduction rate with the active exosuit was generally higher than with passive exoskeleton in the lift up sessions. This indicates that the proposed active exosuit more effectively reduces the effort and fatigue of wearer’s back muscles compared to the investigated passive exoskeleton. Previous studies have suggested that active exosuits typically achieve greater muscle activity reduction than passive ones19,80. This is likely due to the greater supportive force or torque provided by active exosuits19,32. However, during the bend down session with the load, the passive exoskeleton demonstrated a relatively greater reduction in EMG than the active exosuit. Potential reason is that the investigated passive exoskeleton provides high supportive torque even at small trunk bending angle (reaches 40% of the maximum supportive torque when the bending angle is within 20°–40°)39, while the active exosuit in current study provides supportive force only when the trunk bending angle is over 60°. The tradeoff in support timing means that while passive exosuits offers early support, it may also impede movement28,33. In the bend down session with load and the lift up sessions with passive exosuit, the mean EMG did not increase, likely due to the load helping to counteract the resistance from the passive exoskeleton, with little adverse effects on the lift up session. These trends align with the implications of movement impediment noted during bend down without load. For active exosuits, the timing of support is influenced by the control algorithm and system, but early support (trunk bending angle < 60°) is likely limited, especially when the user is holding weight19. Optimizing the timing for support warrants further investigation and could guide future designs of active back exoskeletons.

Figure 3b presents the average peak EMG of the back extensors in the corresponding four sessions. Overall, the peak EMG was significantly reduced when performing tasks both without and with load while wearing active exosuit. In contrast, significant reduction in peak EMG were observed only during tasks with load when wearing passive exoskeleton. Though not statistically significant, the passive exoskeleton showed a trend toward reduced peak EMG during lifting up without load. Notably, the trend of increasing the peak EMG in bend down session without load when wearing passive exoskeleton (6.79%) was also observed, which reinforces the effects of movement impediment previously stated. The peak EMG was reduced by 26.04–31.64% with active exosuit across all conditions and was reduced by 16.62–17.33% with passive exoskeleton when performing with load. In terms of bending down and lifting up with 25 kg load, the results presented in the current study confirm the effectiveness of both exosuits to reduce the peak back muscle activity. As it was found that peak EMG is synchronous with peak muscle–tendon stretch, and greater stretch leads to greater risk of muscle and joint injuries71,72, the reduced peak EMG in current study suggests that both exosuits reduced the risk of low back injury during repetitively lifting weight. Furthermore, the peak EMG was consistently lower with active exosuit than with passive exoskeleton, suggesting that the proposed active exosuit greater reduces the risk of back injury than the investigated passive exoskeleton. Additionally, significant gender differences were limited to height (males: 180.0 ± 5.8 cm; females: 165.0 ± 4.4 cm; p < 0.05), with no significant between-group difference was observed in average mean and peak EMG or body weight.

To further investigate the effects of the exosuits on EMG variation during the tasks, the EMG curve under each condition was normalized in time by the percent of motion cycle. The compared EMG curves are presented on Fig. 4. Most peaks of the EMG curves were observed within the range of 30–40% of the motion cycle. As the lumbar erector spinae, or the back extensor, reaches the highest muscle activity at a trunk flexion angle of about 45°81, this angle is likely reached within 30–40% of the motion cycle, explaining the observed peak of the EMG curve in this range. Three expectations were observed in the results: a delay in bend down without load when wearing passive exoskeleton (50–60%), and two advances respectively in lift up without load when not wearing exosuit (20–30%) and lift up with load when wearing active exosuit (20–30%). For the delayed case, it can be deduced that during early trunk bending (20°–40°), the passive exoskeleton provides relatively high supportive torque (40% of maximum supportive torque)39. Therefore, the wearer needs to exert greater effort to overcome this torque, leading to a prolonged early stage of bending down and a delayed peak in the EMG curve, as well as an increase in EMG level. When lifting without wearing an exosuit, subjects likely needed to apply considerable muscle force to initial movement or break the balanced state of the trunk82. Compared to lifting up without weight when not wearing exosuit, the peaks of lift up with weight when not wearing exosuit as well as wearing passive exoskeleton delayed to 30–40% of the motion cycle. This delay may be because of the early stage (0–30% of the motion cycle), subjects are only lifting their trunk while grabbing the weight without actually lifting it. When they begin lifting the weight (30–40% of the motion cycle), the EMG increase continuously until the peak is reached, leading to peak delay compared to lift up without weight. As during lifting up process, the supportive torque of the passive exoskeleton is decreasing39, and it results in a lower EMG level of lift up with load when wearing passive exoskeleton during the early stage (0–30% of the motion cycle) than not wearing exosuit, and ultimately reaching a peak at a similar stage as not wearing exosuit. In contrast, the peak for lifting up with load while wearing the active exosuit occurred earlier (20–30% of the motion cycle). Since the supportive force of the active exosuit is less related to the trunk bending angle, it is plausible that the supportive force remains substantial at this stage, allowing the force required to lift up at 30–40% of the motion cycle to be compensated by the active exosuit’s support.

Usability evaluation by subjective measurements

The results of the subjective ratings for each item of NASA-TLX are displayed in Fig. 5. Overall, the differences between conditions for each item were not statistically significant. Although not statistically significant, trends were observed, indicating increases or decreases in item scores with the use of exosuits. For mental demand (MD), scores showed trends of decrease with both the active exosuit and passive exoskeleton, suggesting that subjects felt more confident performing tasks with the back exosuit. The variation in mental demand scores may relate to peak shifts in EMG patterns during the tasks, indicating that these shifts could influence mental load. However, the relationship between EMG patterns and mental load is not well-studied, indicating a need for further research. Physical demand (PD) scores were similar across the three conditions. This consistency may be attributed to the relatively heavy 25 kg load, along with the tasks lasting a considerable duration, which could make subjects less sensitive to physical effort. The higher physical demand and poorer performance (P) observed with passive exoskeleton compared to no exo might be due to the movement impediment effects mentioned in section “Performance evaluation by back muscle activity test”.

Discussion

The current study compares two back exosuits from two representative types, namely SV Exosuit proposed by the authors that is active and soft and IX BACK that is passive and rigid. SV Exosuit (2.06 kg) is lighter than half the weight of IX BACK (4.47 kg). The storage size of SV Exosuit is significantly smaller than that of IX BACK. The lighter weight and compact size of SV Exosuit imposes less additional burden and retains accessibility and maneuverability in confined or intricate workspaces often encountered in construction settings. The study involved tasks of bending down and lifting up, both with and without a 25 kg load under three conditions, namely no exo, with active exosuit, and passive exoskeleton. The effects of these two devices on task effectiveness and usability were compared. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, it is the first study to compare the performances of a soft active back exosuit and a rigid passive back exosuit under identical experimental conditions, providing valuable reference for potential users and practitioners in product selection.

Effects on muscular activity

Effectiveness was assessed by comparing the mean and peak EMG variations during task performance with and without the back exosuits. The results of the mean EMG confirm the effectiveness of both exosuits to reduce mean back muscle activity when lifting and lowering objects weighing up to 25 kg. Considering the reduced mean EMG is usually regarded as an indicator of muscle fatigue and effort reduction69,83, it is suggested that both exosuits applied in current study significantly lessen user effort when repetitively lifting and bending down with a 25 kg load. The reduced mean EMG percentages align with previous studies, which reported mean EMG reductions of 10% to 57% during similar tasks with various exoskeletons44,67,84,85. In our prior study, subjects were asked to bend down and lift up wearing our proposed exosuit without holding weight, and showed mean EMG reductions of 13.02–37.02%21, similar to current findings. Variations between the results can stem from several factors. On the one hand, the sEMG electrodes were attached to not exactly the same positions. Compared to the previous study that investigated two pairs of muscles, the current study streamlined the experiment procedure to focus on one pair of muscles building on prior findings demonstrating similar activation trends across the two pairs of muscles21,86. On the other hand, the subjects in the previous study were required not to bend their knees when performing the tasks, while the current study allowed them to perform as they prefer out of safety consideration, as 25 kg can cause a heavy load to the low back. In the current study, if the subject prefers to use their leg muscles when lifting up, the expected back muscle force might be shared by leg muscles, and the EMG reduction provided by the exosuit is thus less significant. Previous research also noted that compared to bending the trunk, squatting shows much higher discomfort in the legs (about 16.7% greater for upper leg and about 75% greater for lower leg) and significantly lower discomfort in the low back (about 87.5% lower)27. Further study is still needed for the influence of back exosuit on the variations in leg muscle activity during lifting tasks.

For the reduction rate of the mean EMG, a similar study observed a mean EMG reduction of 12–18%, which is relatively lower than the results of the current study87. One possible reason is that the lifted weight in their study was 10 kg that is lighter than 25 kg used in the current study. It appears that within a certain weight range, heavier loads may lead to more significant support effects from back exoskeletons. This trend is observed in the current study, where with active exosuit, the reduced mean EMG in lift up with load (27.81%) was greater than without (23.57%), and with passive exoskeleton, the reduced mean EMG in lift up with load (17.11%) was also greater than without (14.17%). A similar trend is also found in a previous study, which reported the reduced mean EMG of performing tasks with 15 kg load (23.2—30%) is greater than without load (12.9–20.3%)38. The impact of lifted weight on the supportive force of back exoskeletons requires further exploration.

Both SV Exosuit and IX BACK reduced mean and peak EMG during the tasks with 25 kg load, indicating effective support in reducing the wearer’s effort and the risk of low back injuries. SV Exosuit demonstrated greater reductions in mean and peak EMG in most sessions, suggesting superior support for heavy lifting. However, during the bending down session with load, IX BACK showed a greater reduction in mean EMG, possibly due to its high early-stage support during trunk bending (trunk bending angle between 20° and 40°)39. In sessions without load, the trend of insignificantly increased mean and peak EMG with IX BACK suggests that its generated torque may impede the wearer’s regular movements, particularly when performing tasks without load. This observation aligns with previous studies28,33,88 indicating the impeding effects of passive exoskeletons. The early support from IX BACK likely contributes to this impediment, highlighting the need for optimization of the relationship between supporting force and bending angle in passive exosuits. Furthermore, EMG curve comparisons revealed that during the bending down session without load, the occurrence of EMG peaks was generally delayed with IX BACK. This delay implies that the torque generated by IX BACK prolongs the initial bending phase, requiring greater effort and time to overcome the torque. Such prolonged early stages may result from wearers’ difficulties in adapting to the exosuit89, indicating a potential need for proper training and adaptation periods to enhance the efficiency of passive back exosuits. Future studies should explore optimal training and adaptation periods.

Several factors can contribute to the results of the EMG curves. The delayed peak in bend down without load when wearing IX BACK may result from users not being accustomed to the back exoskeleton89, indicating that proper adaptation or training is necessary to improve exoskeleton efficiency and user experience. The EMG curves can also be affected by the changes in hip and knee angles. These angles can be influenced by the back exosuit throughout the lifting cycle90, affecting trunk movement during the cycle. Further study is needed to investigate the relationship between trunk motion, EMG patterns, and supportive torque or force.

The variation in EMG can be significantly influenced by the supportive torque provided by the back exosuits. Previous research indicates that SV Exosuit can deliver approximately 54 Nm of supportive torque21, and IX BACK can provide nearly 49 Nm of supportive torque39. This difference may help explain the observed reduction in EMG in the current experiment. However, supportive torque is influenced by numerous factors, including the adjustable supporting gear, misalignment between the device and the wearer, performance discrepancies of the device between flexion and extension, and the control strategy or torque–angle curve21,39,91. Yet existing studies offer limited information on this topic. For the two exosuits compared in this study, SV Exosuit primarily lacks a torque–angle curve because its control strategy is not based on angle, whereas the IX BACK lacks torque performance data under various supporting gear conditions39. This gap suggests that further investigation into the force or torque curves of the back exosuits could provide valuable insights into their differences in support. Additionally, the physique and gender of the wearer can be potential reasons affecting the EMG variation. Though the heights of male participants were significantly higher than female, no significant gender-related difference was revealed in EMG outcomes. This finding may be explained by several biomechanical and methodological factors. Firstly, while morphological differences exist between males and females92, EMG signals primarily reflect muscle activation instead of muscle force45,46, potentially attenuating observable gender effects. This result aligns with a previous finding that shows no significant gender differences in trunk extensor EMG during similar tasks22. Secondly, since back exosuits provide supportive forces mainly at shoulders and thighs, upper body segment lengths likely influence exosuit efficacy more substantially than total body height. Further study is needed to investigate the effects. Moreover, the sample sizes are modest and imbalanced between the gender groups and might affect statistical power. Future research to investigate how the physique and gender of the wearer influence exoskeleton performance will be valuable. Overall, considering weight, size, effects on muscle activity reduction, and movement impediment effects, SV Exosuit is likely to provide better support for workers involved in lifting tasks in construction environments compared to IX BACK.

Effects on usability

For the scores of the subjective evaluation, the differences between conditions for each item were not statistically significant. Similarly, a previous research did not find significant differences in subjective ratings among conditions of no exo, with Cray X (an active back exosuit), and with IX BACK in tasks involving object lifting93. This may be because the ratings were based on the effect of the exosuit on the tasks both with and without load, making it challenging for subjects to provide an overall evaluation when combing sessions with and without load. Additionally, the participant cohort lacked representation of experienced construction workers, potentially limiting the usability evaluation. Future studies should consider these factors when conducting subjective evaluations. Moreover, subjective evaluation is related to cognitive load, which might show different trend from objective measurement like EMG93,94. The relationship between task difficulty and perceived cognitive load requires further investigation.

Limitations and future directions

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. The comparison was limited to two back exosuits. The results, particularly regarding usability, may not generalize to other devices. The effects of the other types of back exosuits (i.e. rigid active and soft passive exosuits) may also provide additional information for cross comparison between types of devices. Evaluating additional exoskeletons would enable more comprehensive insights.

The study focused on the effects of the back exosuits on symmetric lifting, and these devices may have different performances with asymmetric lifting. Additionally, the effects on other non-lifting activities such as walking, stair climbing, and squatting were not considered, and investigation with these activities can provide valuable information for further investigation, especially in terms of user usability. Furthermore, exploring how adaptation periods for back exosuits affect task performance, as well as variations in adaptation across different devices, could be fruitful areas for future study. Therefore, field studies are required to evaluate real-world applicability.

The modest sample size and participants’ lack of specialized construction experience limited the subjective usability assessments. Since construction tasks are diverse and workers adopt different strategies to perform the tasks, the workers can have different usability assessments. The usability assessments can also be varied when wearing the device for longer working duration and period. Recruiting industrial practitioners to perform long-term tests can provide enhanced usability assessment.

Conclusion

This study provides comparative information on a soft active exosuit previously developed by the authors, SV Exosuit, and a commercially available rigid passive exoskeleton, IX BACK. SV Exosuit weighs 2.06 kg, less than half the weight of IX BACK (4.47 kg), and has a more compact storage size. Both devices significantly reduced mean and peak EMG during bending down and lifting with the 25 kg load, confirming their effectiveness in weightlifting. The reduced mean EMG indicates that both back exosuits assist in decreasing the wearer’s effort in lifting tasks with the load, while the reduced peak EMG suggests a lowered risk of low back injuries. Notably, SV Exosuit demonstrated greater reductions in mean and peak EMG compared to IX BACK, indicating its superior capacity to alleviate the wearer’s effort and further mitigate the risk of low back injuries. The peak shift in the EMG curve while bending down without load indicates the potential movement impediment of IX BACK. Overall, considering weight, size, effectiveness of muscle activity reduction, and movement impediment effects, SV Exosuit is likely to provide better support for workers involved in lifting tasks in construction environments compared to IX BACK. Future research should investigate muscle activity variations in other major body parts involved in lifting tasks, such as the abdomen, thighs, and hips, while using back exosuits. Additionally, comparing the force curves of these two devices, exploring the effects of adaptation periods on task performance, and assessing their performance in real construction sites will be valuable directions for future studies.

Data availability

Some or all data that supports the findings of this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Adhikari, B. et al. Factors associated with low back pain among construction workers in Nepal: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 16, e0252564. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252564 (2021).

Chung, J. W. Y. et al. A survey of work-related pain prevalence among construction workers in Hong Kong: A case-control study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16081404 (2019).

Jeong, S. & Lee, B.-H. The moderating effect of work-related musculoskeletal disorders in relation to occupational stress and health-related quality of life of construction workers: A cross-sectional research. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 25, 147. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-024-07216-4 (2024).

Botelho, J. et al. Economic burden of periodontitis in the United States and Europe: An updated estimation. J. Periodontol. 93, 373–379. https://doi.org/10.1002/JPER.21-0111 (2022).

Carregaro, R. L. et al. Low back pain should be considered a health and research priority in Brazil: Lost productivity and healthcare costs between 2012 to 2016. PLoS ONE 15(4), e0230902. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0230902 (2020).

Alonso-García, M. & Sarría-Santamera, A. The economic and social burden of low back pain in Spain: A national assessment of the economic and social impact of low back pain in Spain. Spine 45, E1026–E1032. https://doi.org/10.1097/brs.0000000000003476 (2020).

Dolan, P., Earley, M. & Adams, M. A. Bending and compressive stresses acting on the lumbar spine during lifting activities. J Biomech 27, 1237–1248. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9290(94)90277-1 (1994).

Di Natali, C., Buratti, G., Dellera, L. & Caldwell, D. Equivalent weight: Application of the assessment method on real task conducted by railway workers wearing a back support exoskeleton. Appl. Ergon. 118, 104278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2024.104278 (2024).

Antwi-Afari, M. F., Li, H., Umer, W., Yu, Y. & Xing, X. Construction activity recognition and ergonomic risk assessment using a wearable insole pressure system. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 146, 04020077. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0001849 (2020).

Subedi, S. & Pradhananga, N. Sensor-based computational approach to preventing back injuries in construction workers. Autom. Constr. 131, 103920 (2021).

Luo, H. et al. Convolutional neural networks: Computer vision-based workforce activity assessment in construction. Autom. Constr. 94, 282–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2018.06.007 (2018).

Tian, W. et al. A review of smart camera sensor placement in construction. Buildings 14, 3930 (2024).

Sherafat, B. et al. Automated methods for activity recognition of construction workers and equipment: State-of-the-art review. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 146, 03120002. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0001843 (2020).

Wang, M., Chen, J. & Ma, J. Monitoring and evaluating the status and behaviour of construction workers using wearable sensing technologies. Autom. Constr. 165, 105555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2024.105555 (2024).

Nykänen, M. et al. Implementing and evaluating novel safety training methods for construction sector workers: Results of a randomized controlled trial. J. Safety Res. 75, 205–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsr.2020.09.015 (2020).

Hussain, R. et al. Conversational AI-based VR system to improve construction safety training of migrant workers. Autom. Constr. 160, 105315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2024.105315 (2024).

Baldassarre, A. et al. Industrial exoskeletons from bench to field: Human-machine interface and user experience in occupational settings and tasks. Front Public Health 10, 1039680. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1039680 (2022).

Walter, T., Stutzig, N. & Siebert, T. Active exoskeleton reduces erector spinae muscle activity during lifting. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2023.1143926 (2023).

Poliero, T., Fanti, V., Sposito, M., Caldwell, D. G. & Natali, C. D. Active and passive back-support exoskeletons: A comparison in static and dynamic tasks. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 7, 8463–8470. https://doi.org/10.1109/LRA.2022.3188439 (2022).

Fanti, V. et al. Multi-exoskeleton performance evaluation: Integrated muscle energy indices to determine the quality and quantity of assistance. Bioengineering 11, 1231 (2024).

Lei, T. et al. Lightweight active soft back exosuit for construction workers in lifting tasks. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 150, 04024073. https://doi.org/10.1061/JCEMD4.COENG-14490 (2024).

Raghuraman, R. N., França, B. D., Jessica, A. & Srinivasan, D. Age and gender differences in the perception and use of soft vs. rigid exoskeletons for manual material handling. Ergonomics 67, 1453–1470. https://doi.org/10.1080/00140139.2024.2338268 (2024).

Mohamed Refai, M. I., Moya-Esteban, A., van Zijl, L., van der Kooij, H. & Sartori, M. Benchmarking commercially available soft and rigid passive back exoskeletons for an industrial workplace. Wearable Technol. 5, e6. https://doi.org/10.1017/wtc.2024.2 (2024).

Di Natali, C. et al. From the idea to the user: A pragmatic multifaceted approach to testing occupational exoskeletons. Wearable Technol. 6, e5. https://doi.org/10.1017/wtc.2024.28 (2025).

Poliero, T. et al. Applicability of an active back-support exoskeleton to carrying activities. Front. Robot. AI https://doi.org/10.3389/frobt.2020.579963 (2020).

Zelik, K. E. et al. An ergonomic assessment tool for evaluating the effect of back exoskeletons on injury risk. Appl. Ergon. 99, 103619. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2021.103619 (2022).

Golabchi, A., Jasimi Zindashti, N., Miller, L., Rouhani, H. & Tavakoli, M. Performance and effectiveness of a passive back-support exoskeleton in manual material handling tasks in the construction industry. Constr. Robot. 7, 77–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41693-023-00097-4 (2023).

Luger, T., Bär, M., Seibt, R., Rieger, M. A. & Steinhilber, B. Using a back exoskeleton during industrial and functional tasks—effects on muscle activity, posture, performance, usability, and wearer discomfort in a laboratory trial. Hum. Factors 65, 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/00187208211007267 (2023).

Bennett, S. T. et al. Usability and biomechanical testing of passive exoskeletons for construction workers: A field-based pilot study. Buildings 13, 822 (2023).

Preethichandra, D. M. G. et al. Passive and active exoskeleton solutions: Sensors, actuators, applications, and recent trends. Sensors 24, 7095 (2024).

Sposito, M. et al. Exoskeleton kinematic design robustness: An assessment method to account for human variability. Wearable Technol. 1, e7. https://doi.org/10.1017/wtc.2020.7 (2020).

Okunola, A., Akanmu, A. A. & Yusuf, A. O. Comparison of active and passive back-support exoskeletons for construction work: Range of motion, discomfort, usability, exertion and cognitive load assessments. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 14, 582–598. https://doi.org/10.1108/SASBE-06-2023-0147 (2025).

Govaerts, R. et al. The impact of an active and passive industrial back exoskeleton on functional performance. Ergonomics 67, 597–618. https://doi.org/10.1080/00140139.2023.2236817 (2024).

Zhu, M., Do, T. N., Hawkes, E. & Visell, Y. Fluidic fabric muscle sheets for wearable and soft robotics. Soft Rob. 7, 179–197. https://doi.org/10.1089/soro.2019.0033 (2020).

Kalita, B., Leonessa, A. & Dwivedy, S. K. A Review on the development of pneumatic artificial muscle actuators: Force model and application. Actuators 11, 288 (2022).

Imamura, Y., Tanaka, T., Suzuki, Y., Takizawa, K. & Yamanaka, M. Analysis of trunk stabilization effect by passive power-assist device. J. Robot. Mechatron. 26, 791–798. https://doi.org/10.20965/jrm.2014.p0791 (2014).

Bianco, N. A., Franks, P. W., Hicks, J. L. & Delp, S. L. Coupled exoskeleton assistance simplifies control and maintains metabolic benefits: A simulation study. PLoS ONE 17, e0261318. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261318 (2022).

Heydari, H., Hoviattalab, M., Azghani, M. R., Ramezanzadehkoldeh, M. & Parnianpour, M. Investigation on a developed wearable assistive device (WAD) in reduction lumbar muscles activity. Biomed. Eng. Appl. Basis Commun. 25, 1350035 (2013).

Van Harmelen, V., Schnieders, J. & Wagemaker, S. Measuring the amount of support of lower back exoskeletons. Laevo White Paper (2022).

Bergmann, L. et al. Lower limb exoskeleton with compliant actuators: Design, modeling, and human torque estimation. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 28, 758–769. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMECH.2022.3206530 (2023).

Schmalz, T. et al. A passive back-support exoskeleton for manual materials handling: Reduction of low back loading and metabolic effort during repetitive lifting. IISE Trans. Occup. Ergon. Human Factors 10, 7–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/24725838.2021.2005720 (2022).

Postol, N. et al. The metabolic cost of exercising with a robotic exoskeleton: A comparison of healthy and neurologically impaired people. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 28, 3031–3039. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNSRE.2020.3039202 (2020).

Malcolm, P., Derave, W., Galle, S. & De Clercq, D. A simple exoskeleton that assists plantarflexion can reduce the metabolic cost of human walking. PLoS ONE 8, e56137. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0056137 (2013).

Alemi, M. M., Geissinger, J., Simon, A. A., Chang, S. E. & Asbeck, A. T. A passive exoskeleton reduces peak and mean EMG during symmetric and asymmetric lifting. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 47, 25–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jelekin.2019.05.003 (2019).

Monteiro-Oliveira, B. B. et al. Use of surface electromyography to evaluate effects of whole-body vibration exercises on neuromuscular activation and muscle strength in the elderly: A systematic review. Disabil. Rehabil. 44, 7368–7377. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2021.1994030 (2022).

Alcan, V. & Zinnuroğlu, M. Current developments in surface electromyography. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 53, 1019–1031 (2023).

Ali, A., Fontanari, V., Schmoelz, W. & Agrawal, S. K. Systematic review of back-support exoskeletons and soft robotic suits. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2021.765257 (2021).

Mitterlehner, L., Li, Y. X. & Wolf, M. Objective and subjective evaluation of a passive low-back exoskeleton during simulated logistics tasks. Wearable Technol. 4, e24. https://doi.org/10.1017/wtc.2023.19 (2023).

Behjati Ashtiani, M. et al. Understanding the drivers of and barriers to adopting passive back- and arm-support exoskeletons in construction: Results from interviews and short-term field testing. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 107, 103732. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ergon.2025.103732 (2025).

Kuber, P. M., Abdollahi, M., Alemi, M. M. & Rashedi, E. A systematic review on evaluation strategies for field assessment of upper-body industrial exoskeletons: Current practices and future trends. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 50, 1203–1231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10439-022-03003-1 (2022).

Okunola, A., Afolabi, A., Akanmu, A., Jebelli, H. & Simikins, S. Facilitators and barriers to the adoption of active back-support exoskeletons in the construction industry. J. Safety Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsr.2024.05.010 (2024).

Al-Khiami, M. I., Lindhard, S. M. & Wandahl, S. Integrating exoskeletons in the construction sector: A systematic review of empirical evaluation tools and future directions. Eng. Constr. Arch. Manage. https://doi.org/10.1108/ECAM-05-2024-0563 (2024).

Gonsalves, N., Akanmu, A., Shojaei, A. & Agee, P. Factors influencing the adoption of passive exoskeletons in the construction industry: Industry perspectives. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 100, 103549. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ergon.2024.103549 (2024).

Zhu, Z., Dutta, A. & Dai, F. Exoskeletons for manual material handling—A review and implication for construction applications. Autom. Constr. 122, 103493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2020.103493 (2021).

Ahmad, J., Fanti, V., Caldwell, D. G. & Di Natali, C. Framework for the adoption, evaluation and impact of occupational Exoskeletons at different technology readiness levels: A systematic review. Robot. Auton. Syst. 179, 104743. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.robot.2024.104743 (2024).

Crea, S. et al. Occupational exoskeletons: A roadmap toward large-scale adoption. Methodology and challenges of bringing exoskeletons to workplaces. Wearable Technol. 2, e11. https://doi.org/10.1017/wtc.2021.11 (2021).

Wehner, M. Lower extremity exoskeleton as lift assist device (University of California, 2009).

Alemi, M. M. Biomechanical assessment and metabolic evaluation of passive lift-assistive exoskeletons during repetitive lifting tasks. Virginia Tech. (2019).

Cardoso, A. et al. Assessing the short-term effects of dual back-support exoskeleton within logistics operations. Safety 10, 56 (2024).

Lamers, E. P., Soltys, J. C., Scherpereel, K. L., Yang, A. J. & Zelik, K. E. Low-profile elastic exosuit reduces back muscle fatigue. Sci Rep 10, 15958. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-72531-4 (2020).

Mäki, T. & Kerosuo, H. Site managers’ daily work and the uses of building information modelling in construction site management. Constr. Manag. Econ. 33, 163–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/01446193.2015.1028953 (2015).

Ciccarelli, M. et al. in 2024 20th IEEE/ASME International Conference on Mechatronic and Embedded Systems and Applications (MESA). 1–8.

Gonsalves, N. J., Ogunseiju, O. O., Akanmu, A. A. & Nnaji, C. A. Assessment of a passive wearable robot for reducing low back disorders during rebar work. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 26, 936–952 (2021).

Statista. Share of female employees in the construction industry in the United States from 2002 to 2024, https://www.statista.com/statistics/434758/employment-within-us-construction-by-gender/ (2025).

Ismaila, O. et al. Manual lifting task methods and low back pain among construction workers in the southwestern Nigeria. Global J. Res. Eng. 13, 419–434 (2013).

Kim, H. K., Hussain, M., Park, J., Lee, J. & Lee, J. W. Analysis of active back-support exoskeleton during manual load-lifting tasks. J. Med. Biol. Eng. 41, 704–714. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40846-021-00644-w (2021).

Madinei, S., Alemi, M. M., Kim, S., Srinivasan, D. & Nussbaum, M. A. Biomechanical assessment of two back-support exoskeletons in symmetric and asymmetric repetitive lifting with moderate postural demands. Appl. Ergon. 88, 103156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2020.103156 (2020).

Park, J.-H., Madigan, M. L., Kim, S., Nussbaum, M. A. & Srinivasan, D. Wearing a back-support exoskeleton alters lower-limb joint kinetics during single-step recovery following a forward loss of balance. J. Biomech. 166, 112069. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2024.112069 (2024).

Goršič, M., Song, Y., Dai, B. & Novak, D. Evaluation of the HeroWear Apex back-assist exosuit during multiple brief tasks. J. Biomech. 126, 110620. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2021.110620 (2021).

Chung, J. et al. Lightweight active back exosuit reduces muscular effort during an hour-long order picking task. Commun. Eng. 3, 35. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44172-024-00180-w (2024).

Franettovich Smith, M. M. et al. Gluteus medius activation during running is a risk factor for season hamstring injuries in elite footballers. J. Sci. Med. Sport 20, 159–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2016.07.004 (2017).

Higashihara, A., Nagano, Y., Ono, T. & Fukubayashi, T. Relationship between the peak time of hamstring stretch and activation during sprinting. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 16, 36–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2014.973913 (2016).

SENIAM. Recommendations for sensor locations in trunk or (lower) back muscles, http://seniam.org/erectorspinaelongissimus.html (1999).

Ghazwan, A., Forrest, S. M., Holt, C. A. & Whatling, G. M. Can activities of daily living contribute to EMG normalization for gait analysis?. PLoS ONE 12, e0174670. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0174670 (2017).

La Bara, L. M. A., Meloni, L., Giusino, D. & Pietrantoni, L. Assessment methods of usability and cognitive workload of rehabilitative exoskeletons: A systematic review. Appl. Sci. 11, 7146 (2021).

Melo, M. S. P. D., Neto, J. G. D. S., Teixeira, J. M. X. N., Gama, A. E. F. D. & Teichrieb, V. in 2019 21st Symposium on Virtual and Augmented Reality (SVR). 170–177 (2019).

Kneisz, L. et al. Objectivation of laryngeal electromyography (LEMG) data: Turn number vs. qualitative analysis. Eur. Archiv. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 277, 1409–1415. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-020-05846-7 (2020).

Huang, H.-Y., Lin, J.-J., Guo, Y. L., Wang, W.T.-J. & Chen, Y.-J. EMG biofeedback effectiveness to alter muscle activity pattern and scapular kinematics in subjects with and without shoulder impingement. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 23, 267–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jelekin.2012.09.007 (2013).

Freitas, M. L. B., Junior, J. J. A. M., La Banca, W. F. & Stevan, S. L. Study of the relevance of gender in the classification of hand gestures by electromyography-based recognition systems. Res. Biomed. Eng. 37, 361–373. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42600-021-00145-4 (2021).

Madinei, S., Alemi, M. M., Kim, S., Srinivasan, D. & Nussbaum, M. A. Biomechanical evaluation of passive back-support exoskeletons in a precision manual assembly task: “Expected” effects on trunk muscle activity, perceived exertion, and task performance. Hum Factors 62, 441–457. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018720819890966 (2020).

Chen, Y.-L., Hu, Y.-M., Chuan, Y.-C., Wang, T.-C. & Chen, Y. Flexibility measurement affecting the reduction pattern of back muscle activation during trunk flexion. Appl. Sci. 10, 5967 (2020).

Lynn, C. W., Cornblath, E. J., Papadopoulos, L., Bertolero, M. A. & Bassett, D. S. Broken detailed balance and entropy production in the human brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118, e2109889118 (2021).

Kermavnar, T., de Vries, A. W., de Looze, M. P. & O’Sullivan, L. W. Effects of industrial back-support exoskeletons on body loading and user experience: An updated systematic review. Ergonomics 64, 685–711. https://doi.org/10.1080/00140139.2020.1870162 (2021).

Alemi, M. M., Madinei, S., Kim, S., Srinivasan, D. & Nussbaum, M. A. Effects of two passive back-support exoskeletons on muscle activity, energy expenditure, and subjective assessments during repetitive lifting. Hum. Factors 62, 458–474. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018720819897669 (2020).

Baltrusch, S. J. et al. SPEXOR passive spinal exoskeleton decreases metabolic cost during symmetric repetitive lifting. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 120, 401–412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-019-04284-6 (2020).

Reimeir, B., Calisti, M., Mittermeier, R., Ralfs, L. & Weidner, R. Effects of back-support exoskeletons with different functional mechanisms on trunk muscle activity and kinematics. Wearable Technol. 4, e12. https://doi.org/10.1017/wtc.2023.5 (2023).

Schmalz, T. et al. A passive back-support exoskeleton for manual materials handling: Reduction of low back loading and metabolic effort during repetitive lifting. IISE Trans. Occup. Ergon. Hum. Factors 10, 7–20 (2022).

Baltrusch, S. J., van Dieën, J. H., van Bennekom, C. A. M. & Houdijk, H. The effect of a passive trunk exoskeleton on functional performance in healthy individuals. Appl. Ergon. 72, 94–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2018.04.007 (2018).

Park, H., Kim, S., Nussbaum, M. A. & Srinivasan, D. Changes in kinematics and muscle activity when learning to use a whole-body powered exoskeleton for stationary load handling. Proc. Human Factors Ergon. Soc. Annu. Meeting 66, 273–274. https://doi.org/10.1177/1071181322661218 (2022).

Poliero, T. et al. in Proceedings of the 14th PErvasive Technologies Related to Assistive Environments Conference 210–217 (Association for Computing Machinery, Corfu, Greece, 2021).

Mallat, R., Khalil, M., Venture, G., Bonnet, V. & Mohammed, S. in 2019 Fifth International Conference on Advances in Biomedical Engineering (ICABME). 1–4 (2019).

Hori, Y. et al. Gender-specific analysis for the association between trunk muscle mass and spinal pathologies. Sci. Rep. 11, 7816. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-87334-4 (2021).

Okunola, A., Akanmu, A., Jebelli, H. & Afolabi, A. Assessment of active back-support exoskeleton on carpentry framing tasks: Muscle activity, range of motion, discomfort, and exertion. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 107, 103716. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ergon.2025.103716 (2025).

Akanmu, A., Okunola, A., Jebelli, H., Ammar, A. & Afolabi, A. Cognitive load assessment of active back-support exoskeletons in construction: A case study on construction framing. Adv. Eng. Inform. 62, 102905. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aei.2024.102905 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledged the first authorship of Mr. Ting Lei and the co-correspondences of Dr. Joon Oh Seo and Dr. Kelvin Heung of this manuscript.

Funding

The authors acknowledged Shenzhen-Hong Kong-Macau S&T Program (Category C) (Grant No. SGDX20201103095203031), Hong Kong Chief Executive’s Policy Unit Public Policy Research Funding Scheme (PPRFS, Grant No. 2023.A6.242.23C), and internal funds from The Hong Kong Polytechnic University for funding this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.H. and T.L. conceived of the presented idea. K.L. improved the device and prepared for the experiment. K.L. and J.X. carried out the experiment. T.L. processed the data. H.L., J.S., and K.H. collected fundings for this study. T.L. wrote the manuscript under the supervision of J.S. and K.H. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript. All authors provided critical feedback and helped shape the research, analysis and manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lei, T., Liang, K., Xu, J. et al. Effects on muscular activity and usability of soft active versus rigid passive back exoskeleton during symmetric lifting tasks. Sci Rep 15, 29839 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14500-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14500-3