Abstract

Studying the biodiversity and multifunctionality relationships of the Hobq Desert shrub ecosystem and its response to environmental factors is crucial for ecological restoration in the region. In this study, we examined variations in biodiversity and ecosystem functioning along a precipitation gradient within the Hobq Desert shrub ecosystem. Using machine learning, we evaluated the predictive contributions of species richness and phylogenetic diversity to ecosystem multifunctionality (EMF) and applied structural equation modeling to analyze the direct and indirect impacts of biotic and environmental factors on multifunctionality. Our findings showed that species richness had a significant positive effect on EMF (p < 0.05), while phylogenetic diversity exhibited a relatively weaker influence, which was statistically non-significant (p = 0.257). Furthermore, species richness was identified as a stronger predictor of both individual ecosystem functions and EMF. Precipitation seasonality had a significant negative effect on EMF, indirectly influencing it through its impact on species richness. These findings highlight the essential role of species richness in maintaining ecosystem functioning within desert shrub ecosystems and emphasize the importance of effective biodiversity management, including both targeted conservation efforts and broad-scale ecological restoration, for preserving EMF under global climate change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Environmental conditions are fundamental determinants of plant community diversity, composition, and ecosystem functioning (EF) at the global scale1. These influences are particularly pronounced in arid and semi-arid regions, where limited water and nutrient availability impose severe constraints on biodiversity and ecological processes. Desert ecosystems, which cover approximately 12% of the Earth’s terrestrial surface and support 6% of the global population2, are highly sensitive to climate and land-use changes; even minor disturbances can trigger disproportionately large impacts on biodiversity and ecosystem functioning3. Given their ecological fragility, understanding how biodiversity–ecosystem functioning (BEF) relationships respond to environmental variability is critical for predicting ecosystem resilience and informing conservation and restoration strategies in drylands.

Biodiversity plays a central role in regulating EF, influencing key ecological processes such as primary productivity, nutrient cycling, and carbon storage4,5,6,7. Early BEF studies focused primarily on taxonomic diversity—particularly species richness (SR)—with consistent evidence showing that higher species numbers tend to enhance EF4,8,9,10. However, SR does not capture evolutionary relationships among coexisting species and may therefore underestimate functional differences within communities11. Phylogenetic diversity (PD), which incorporates the evolutionary history of species, has been proposed as a more informative predictor of EF12,13. Nonetheless, empirical evidence remains inconclusive, with some studies suggesting that SR outperforms PD14, especially in arid environments15. These inconsistencies underscore the importance of jointly evaluating multiple dimensions of biodiversity to improve our understanding of BEF relationships, particularly in water-limited systems.

In addition, ecosystem functioning is inherently multidimensional. Assessing biodiversity effects based on a single function may underestimate its ecological importance. To address this limitation, the concept of ecosystem multifunctionality (EMF) has been introduced to capture the simultaneous performance of multiple ecosystem functions16. Recent studies have shown that biodiversity tends to be more strongly associated with EMF than with individual functions17. However, the strength and direction of biodiversity–ecosystem multifunctionality (BEMF) relationships vary across environmental gradients, suggesting that both biotic and abiotic factors modulate these interactions18,19. Despite growing interest, few studies have explicitly examined how environmental drivers shape BEMF relationships20. Moreover, most existing studies have relied on observational data or focused on single environmental variables18,21,22,23, limiting our understanding of the complex pathways through which biodiversity and environmental conditions jointly affect EMF. In desert ecosystems, environmental factors such as precipitation, temperature, and soil pH are key regulators that may influence EMF directly or indirectly via their effects on biodiversity15,24.

The Hobq Desert, China’s seventh-largest desert, is located in the transitional zone between arid and semi-arid climates and serves as a strategic component of the national “three key areas and four belts” ecological security framework25. Over recent decades, extensive ecological restoration programs have markedly improved vegetation cover and ecosystem stability. Nevertheless, the interrelationships among species diversity, phylogenetic diversity, and ecosystem functioning in shrub-dominated systems remain poorly understood, constraining the development of targeted conservation and management strategies.

To address these gaps, this study investigates how SR, PD, and environmental factors jointly influence EMF in the Hobq Desert shrubland. Specifically, we assess five key ecosystem functions—aboveground productivity, soil organic carbon, total nitrogen, available phosphorus, and available potassium—and evaluate the regulatory roles of climatic and edaphic variables. We apply machine learning techniques to quantify the predictive power of SR and PD, and employ structural equation modeling (SEM) to disentangle their direct and indirect effects on EMF.

This study addresses two core questions: (1) Which dimension of plant diversity better predicts EMF? (2) How do biodiversity and environmental factors interact to influence EMF? We propose two hypotheses: (H1) Both SR and PD positively contribute to EMF, with SR being the stronger predictor based on previous desert studies; and (H2) environmental factors, particularly mean annual precipitation (MAP) and soil pH, mediate biodiversity–EMF relationships. Specifically, higher MAP is expected to promote biodiversity and EMF, whereas increased pH may suppress SR and associated functions.

By explicitly testing these hypotheses, this study aims to enhance the understanding of BEMF relationships in arid shrub ecosystems and provide theoretical support for their conservation and management.

Materials and methods

Study area and sites sampled

The Hobq Desert is located in the southwestern region of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, China, with geographic locations of 107°00′ − 111°30′E latitude and 39°15′ − 40°45′N longitude. The Hobq Desert is distributed mainly throughout the northern part of the Ordos Plateau and spans the three administrative districts of Hangjin Banner, Dalat Banner and Jungar Banner in Ordos city, Inner Mongolia, with an area of approximately 18,600 square kilometers26. The Hobq Desert features a typical temperate continental arid monsoon climate characterized by large temperature fluctuations, with extreme temperatures ranging from − 30.5 °C to 38.1 °C. Annual precipitation varies between 150 and 400 mm, while annual evaporation ranges from 2100 to 2955 mm. Precipitation decreases progressively from east to west, with the majority occurring in July and August27. The soils in the area are mainly wind-sand soils, and the main plant species in the area are Artemisia ordosica, Agriophyllum pungens, and Corispermum candelabrum28.

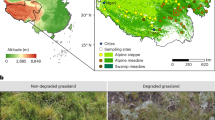

The Hobq Desert exhibits a distinct east-to-west precipitation gradient (Fig. 1a). To investigate this gradient, we selected 10 sites across the region that had been ungrazed for at least three years prior to the study (Fig. 1a), ensuring that recent grazing activities did not confound biodiversity and ecosystem function relationships. All sites were located on flat terrain to minimize topographic effects, and site selection considered soil properties to ensure they were representative of the region’s dominant soil types. Extreme conditions, such as highly saline or severely degraded soils, were avoided to prevent potential biases in ecosystem multifunctionality. While historical grazing intensity prior to exclusion was not quantified, sites were chosen from areas with minimal anthropogenic disturbance beyond the controlled exclusion period, allowing us to focus on the natural variability in biodiversity and environmental drivers.

Study area, field sampling sites, and sample plot settings. The map was created using QGIS version 3.40 (QGIS Development Team; https://qgis.org/).

We selected 100 m × 100 m areas in the centre of each site to visually select areas with relatively homogeneous environments, this plot size is consistent with previous studies in arid and semi-arid ecosystems, ensuring sufficient spatial coverage while capturing vegetation heterogeneity and soil variability29,30. Five 10 m × 10 m shrub samples were set up at the four corners and diagonal intersections of the 100 m × 100 m area, and one 1 m × 1 m herb sample was set up at the diagonal intersection of each shrub sample (Fig. 1b). Vegetation surveys were conducted during the 2019 growing season (July to August) by counting the individuals of each species at each sample site to assess species abundance. All recorded plant species and their taxonomic information are summarized in Table S1.

Data collection

Climatic data, including mean annual temperature (MAT), mean annual precipitation (MAP), and precipitation seasonality (PS), were obtained from the WorldClim database (www.worldclim.org), a global high-resolution dataset31. These variables are critical for understanding ecosystem structure and function in dryland regions32showed minimal correlation at our study sites, and provided a detailed characterization of the climatic conditions.

At each site, five ecosystem functions linked to the cycling and storage of carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus were measured: aboveground biomass (AGB) per unit area, total nitrogen (TN), soil organic carbon (SOC), soil available phosphorus (AP), and soil available potassium (AK)33,34. The plants in each shrub and herbaceous sample plot were mowed flush and oven-dried at 60 °C for 48 h until reaching a constant weight to determine the AGB. The drying temperature of 60 °C was selected to effectively remove moisture while preventing potential organic matter degradation, ensuring accurate biomass measurement, as commonly applied in ecological studies. At each survey site, five 10-cm-deep soil samples were randomly collected using a soil sampler, combined into composite samples, air-dried, and passed through a 2-mm sieve for analysis. SOC was measured using the potassium dichromate oxidation method35, TN analyzed with an elemental analyzer (Various MACRO cube, Germany), AP was determined using the molybdenum-antimony colorimetric method, and AK was measured using the flame photometer method36. Also, soil pH was measured as an environmental factor affecting ecosystem functions. Although precipitation is the primary water input in desert ecosystems, soil moisture availability also plays a crucial role in ecosystem functions. However, given the high temporal variability of soil moisture in arid environments, a single measurement during the survey period would not adequately represent long-term soil moisture conditions. Therefore, we used MAP as a proxy for water availability across sites.

Diversity and multifunctionality assessment

All analyses were conducted using R Statistical Software (v4.2.3)37. Species descriptions were standardized based on the surveyed species lists using the Flora of China (http://www.iplant.cn/frps) and the Plant List (http://www.theplantlist.org/)3. The phylogeny of the recorded species was built with the “V.PhyloMaker2” package38 and visualized using the “ggtree” package39 (Fig. S1). We calculated SR and PD via the ‘picante’ package40, which represents different dimensions of biodiversity at each site. Ecosystem multifunctionality at each site was calculated using the mean method, which involves averaging the Z scores of six ecosystem functions, offering a simple and interpretable measure of the ability to maintain multiple functions concurrently41.

Statistical analysis

We used a general linear model to analyze patterns of diversity, single ecosystem functioning, and ecosystem multifunctionality along a precipitation gradient, treating MAP as a continuous predictor, aiming to observe their changes across the gradient. Model residuals were tested for normality, and when assumptions were not met, non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis tests were applied.

To determine which dimension of plant diversity (species or phylogeny) is a stronger predictor of ecosystem functioning in the Hobq Desert, we analyzed the correlations between biotic and environmental factors and ecosystem functioning using Spearman correlation, with statistical analyses conducted in SPSS 27 software (IBM., Chicago, IL, USA).

We subsequently applied machine learning to generate Partial Dependence Plots (PDPs) and Individual Conditional Expectation (ICE) curves to evaluate how SR and PD influence individual ecosystem functions and EMF. PDPs illustrate the marginal effect of a focal variable (SR or PD) on predicted outcomes while averaging over the influence of other predictors. ICE curves, in contrast, display the prediction trajectory for each individual observation, offering insights into prediction heterogeneity42. During computation, MAP, PS, MAT, and soil pH were held constant at their respective means to reduce confounding effects and isolate the independent contributions of SR and PD.

A conceptual framework illustrating the hypothesized causal relationships among climate factors, soil pH, biodiversity metrics, and ecosystem multifunctionality (Fig. S2) was developed to guide model specification. To explore the direct and indirect effects of biodiversity and environmental factors on ecosystem EMF, we constructed a SEM using AMOS 28 (Amos Development Corporation, Crawfordville, FL, USA). The initial model included SR, PD, MAP, PS, MAT, and soil pH as predictors of EMF. Model refinement involved sequentially removing non-significant pathways based on regression weights, while retaining all predictor variables to preserve theoretical completeness. Model selection was guided by the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). Model fit was assessed using the chi-square test (χ²), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the comparative fit index (CFI), and the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), with thresholds following widely accepted SEM standards43 (RMSEA < 0.08; CFI > 0.90). To ensure the robustness of parameter estimation, multicollinearity among environmental predictors was examined using pairwise correlation coefficients, all of which were below 0.80, indicating acceptable levels of collinearity.

Results

Changes in biodiversity, individual ecosystem functions and EMF

There were significant differences in biodiversity, individual ecosystem functioning, and EMF under the influence of the MAP gradient (Table S2). SR, PD, SOC, and TN significantly increased with increasing MAP (Fig. 2a, b, d and e), and AK and AP significantly decreased with increasing MAP (Fig. 2f and g). Neither AGB nor EMF showed significant correlations with MAP (Fig. 2c and h).

The impact of precipitation on diversity, individual ecosystem functions and EMF. a, species richness (SR); b, phylogenetic diversity (PD); c, aboveground biomass (AGB); d, soil organic carbon (SOC); e, total soil nitrogen (TN); f, soil active phosphorus (AP); g, soil active potassium (AK); h, ecosystem multifunctionality (EMF).

Predictive effects of species richness and phylogenetic diversity on single ecosystem functions and ecosystem multifunctionality

SOC and TN were significantly positively correlated with SR and PD and significantly negatively correlated with MAT and soil pH, whereas the opposite was true for AP and AK (Fig. 3). AGB increased with increasing SOC, which was positively correlated with TN (Fig. S3), but did not significantly correlate with other factors (Fig. 3). EMF had a greater positive correlation with SR than with PD and was significantly negatively correlated with PS; furthermore, no significant regression relationships were identified between EMF and MAT or soil pH (Fig. 3).

Machine learning-based generation of PDPs and ICEs revealed that SR exhibited a consistently positive association with all single ecosystem functions and EMF, whereas the effects of PD were more variable, particularly at higher diversity levels (Fig. 4). Overall, SR demonstrated a more stable and stronger relationship with single ecosystem functions and EMF across the diversity gradient compared to PD (Fig. 4).

Partial dependence plots (PDPs) and individual conditional expectation (ICE) curves showing the effects of species richness (SR) and phylogenetic diversity (PD) on individual ecosystem functions and ecosystem multifunctionality (EMF). Panels a-l correspond to model-predicted responses of: (a, b) aboveground biomass (AGB); (c, d) soil organic carbon (SOC); (e, f) soil total nitrogen (TN); (g, h) soil available phosphorus (AP); (i, j) soil available potassium (AK); and (k, l) EMF. In each panel, the solid blue line represents the smoothed PDP, the grey shaded area indicates the 95% confidence interval, and the dashed lines show ICE curves for individual observations.

Relationships among plant diversity, environmental factors and EMF

The final SEM explained 68% of the variation in EMF and exhibited a good fit to the data (χ² = 5.76, p > 0.05; RMSEA = 0.048; CFI = 0.970; TLI = 0.956), indicating no significant missing paths among unconnected variables (Fig. 5).

Structural equation model (SEM) showing the direct and indirect effects of climatic and edaphic variables on ecosystem multifunctionality (EMF) through biodiversity components. The model includes climate factors (precipitation seasonality [PS], mean annual precipitation [MAP], mean annual temperature [MAT]), soil pH, and biodiversity metrics (species richness [SR], phylogenetic diversity [PD]) as predictors of EMF. Solid arrows represent significant paths (p < 0.05); dashed arrows denote nonsignificant paths. Standardized path coefficients are shown alongside each arrow, with arrow widths scaled proportionally to their absolute values. The R² value is shown next to EMF. Model fit indices: χ²/df = 1.364, CFI = 0.970, RMSEA = 0.048.

Among the predictors, SR had a significant direct positive effect on EMF (β = 0.679, p < 0.05). In contrast, PS showed a direct negative effect on EMF (β = −0.736, p < 0.05). In addition, MAP, PS, and soil pH indirectly influenced EMF via their effects on SR, highlighting the mediating role of biodiversity in linking environmental variability to ecosystem functioning. Although PD and MAT were retained in the model, their effects on EMF were not statistically significant.

Discussion

Although ecosystem multifunctionality is essential for sustainable desert ecosystem development, a clear understanding of how biotic and environmental factors affect ecosystem multifunctionality is lacking. Although environmental factors play a key role in biodiversity, how they directly or indirectly affect ecosystem multifunctionality remains largely unknown. Here, we argue that SR is a better predictor of EMF than PD is in desert ecosystems and that environmental factors (MAP, PS, MAT, and soil pH) directly or indirectly mediated by SR significantly modulate BEMF relationships in desert ecosystems.

Impacts of precipitation on single ecosystem functions and EMF

Precipitation triggers alterations in multiple ecosystem functions, such as plant productivity and nutrient cycling, thereby exerting broad influences on ecosystem functioning15,44. Desert ecosystems are particularly sensitive to changes in precipitation patterns, with both their structure and function responding strongly to shifts in water availability. Consistent with previous studies, our results show that natural precipitation gradients effectively explain variations in SR45,46. In particular, higher precipitation supports the establishment of more drought-intolerant species, leading to increased community PD47.

However, we did not observe significant positive correlations between precipitation and either AGB or EMF (p > 0.05). The weak response of AGB to precipitation may reflect the effects of nutrient-poor soils and multiple co-limiting factors that constrain plant productivity in arid environments48. Additionally, Zhu et al. reported that increased precipitation can reduce shrub dominance by promoting herbaceous plant growth49so in communities where A. ordosica is dominant, this compositional shift may offset net gains in biomass. Furthermore, a large scale assessment of terrestrial ecosystem functioning showed that the first principal component, which represents maximum productivity, explained only part of the total functional variation (71.8% of the spatial variance and 39.3% of the dominant variance), suggesting that productivity alone may not fully represent multifunctionality50.

Despite the absence of a significant correlation between AGB and precipitation in this study, we observed consistent changes in soil nutrient status along the precipitation gradient: SOC and TN increased, while AP and AK decreased. These patterns were likely influenced by biomass-related processes, such as enhanced plant growth and organic matter input under higher water availability. Prior research suggests that precipitation can stimulate belowground biomass and litterfall, contributing to soil carbon and nitrogen accumulation51,52. In contrast, the reduction in AP and AK may result from increased leaching of soluble nutrients under higher precipitation, a process commonly observed in arid and semiarid regions53. This highlights the complexity of precipitation–function relationships and suggests that EMF responses to precipitation may be decoupled from aboveground productivity due to alternative nutrient-mediated pathways.

Species richness and phylogenetic diversity as predictors of ecosystem functioning

Biodiversity has been widely shown to enhance ecosystem multifunctionality by promoting key ecological processes such as productivity and nutrient cycling54,55. In this study, PDP and ICE provided further insights into how SR and PD influence EMF. Machine learning modeling results demonstrated that SR exhibited a consistently positive association with all single ecosystem functions and EMF, whereas PD showed more variability, particularly at higher diversity levels. This suggests that while SR plays a more stable role in maintaining multiple ecosystem functions.

The observed patterns align with the majority of studies emphasizing the pivotal role of biodiversity in driving EMF8,10. Biodiversity enhances the ability of ecosystems to maintain multiple functions by increasing the likelihood of functionally complementary species coexisting, thereby stabilizing ecosystem processes across temporal and spatial scales56,57. Our machine learning modeling results reinforce this perspective, showing that as SR increases, EMF consistently improves, reflecting the strong functional complementarity among species.

In contrast, the effect of PD on EMF was less predictable. Our findings suggest that a sustained increase in PD may have contrasting effects on EMF depending on ecological context. Greater evolutionary divergence in a community implies a higher probability of resource partitioning, which can increase resource use efficiency. However, higher PD may also intensify interspecific competition by introducing functionally diverse species that compete for similar resources58, potentially weakening the dominance of A. ordosica—a key species contributing to EMF through selection effects, when PD increases, competitively weaker species with divergent functional strategies may establish and persist, diluting the contribution of dominant species like A. ordosica to ecosystem functioning59. This supports findings that in resource-limited environments, functional convergence among dominant species is critical for maintaining ecosystem processes, whereas excessive diversification may disrupt stabilizing selection effects60,61.

Taken together, our results indicate that while SR consistently enhances EMF, PD’s effects are more context-dependent, shaped by species interactions, resource availability, and competitive dynamics. Moreover, high SR and PD do not necessarily maximize all functions simultaneously62. Evaluations of global restoration projects indicate that even after decades, ecosystems only partially recover their functions63, suggesting that SR and PD alone cannot fully explain variations in EMF. Thus, multiple biodiversity attributes, including FD, should be integrated into future research to disentangle their effects on EMF64,65.

Effects of biotic and environmental factors on EMF

This study highlights the direct and indirect influences of climatic factors and soil pH on the multifunctionality of desert ecosystems, underscoring the critical role of climate and edaphic properties in shaping and driving changes in ecosystem functions. Ecosystem functioning is strongly modulated by environmental conditions and the diversity and characteristics of species within ecological communities66. Climate and soil properties are particularly influential in arid ecosystems under ongoing global environmental change7. Although rising temperatures can exert both positive and negative effects on ecosystem functioning67,68, and ecosystems may remain functionally stable within specific temperature thresholds69, our results showed that MAT had no significant effect on EMF. This may be explained by the relatively moderate and irregular temperature variation in the study region, which does not exceed the physiological tolerance of dominant desert species.

Among the climatic drivers, water availability emerged as a key limiting factor, particularly its temporal variability. Xu et al. emphasized that seasonal and interannual variability in precipitation plays a critical role in controlling community biomass accumulation70, while Ye et al. found that increased interannual precipitation variability reduced grassland productivity on the Tibetan Plateau71. Consistent with these findings, our results indicate that PS had a significant direct negative effect on EMF, likely due to increased climatic instability limiting resource availability and plant productivity.

In contrast to the direct effects of PS, MAP influenced EMF through an indirect pathway. In our model, MAP had a significant negative effect on soil pH, suggesting that increased precipitation may promote soil acidification in arid regions72. Soil pH, in turn, exhibited a significant negative effect on SR, this is consistent with findings that soil pH is typically negatively correlated with richness at low latitudes73. In addition to this pH-mediated effect, MAP also exerted a direct positive influence on SR, likely reflecting the facilitative role of water availability in promoting plant establishment and coexistence. Together, these results reveal that MAP enhances SR through both direct and edaphic-mediated pathways, and given the strong positive effect of SR on EMF, this dual mechanism illustrates how long-term precipitation regimes shape multifunctionality via cascading biotic and abiotic processes.

While MAP served as a proxy for water input in this study, it may not fully capture the dynamics of soil moisture, which more directly governs microbial activity, nutrient turnover, and plant water uptake. Due to its high temporal variability in arid environments, which is driven by rapid evaporation and infiltration, soil moisture may introduce additional uncertainty into patterns of ecosystem functioning. Incorporating direct measurements of soil moisture in future studies would provide more accurate insights into its regulatory role in biodiversity–function relationships and help disentangle the effects of precipitation quantity versus water availability on EMF.

Limitations and future directions

While our study provides valuable insights into the relationships among biodiversity, environmental factors, and EMF, it is important to acknowledge several limitations. First, the analysis is based on observational data, which restricts the ability to infer causality. Although SEM allows for the examination of direct and indirect relationships among variables, it cannot establish causal links without experimental validation. In addition, the study relied on data collected from a single year across ten sites, which may not capture interannual variation or broader spatial heterogeneity in BEMF relationships. In particular, water availability, especially soil moisture, varies substantially across time and space, potentially influencing plant resource acquisition and ecosystem processes in ways that cannot be fully explained by precipitation patterns alone.

Moreover, while species richness showed a consistent positive effect on EMF, the influence of PD appeared to be more context-dependent, likely due to functional convergence among arid-adapted species. However, our study did not incorporate FD, which limits our ability to fully disentangle the mechanisms underlying BEMF relationships. Functional traits such as specific leaf area, root morphology, or tissue nutrient content mediate key ecological processes and should be included in future studies to provide deeper mechanistic insights74,75. Integrating FD with taxonomic and phylogenetic diversity would allow for a more comprehensive understanding of how biodiversity supports ecosystem multifunctionality under different environmental conditions.

Additionally, while the mean z-score method provides a useful, standardized measure of EMF, it may obscure potential trade-offs between individual ecosystem functions. Future studies could explore complementary approaches, such as using multivariate EMF indices or function weighted averaging, to more precisely capture how biodiversity supports multiple functions. Expanding the spatial and temporal scope of research, combined with the use of remote sensing and long-term monitoring (e.g., of soil moisture and functional traits), will also be critical for assessing how biodiversity and environmental drivers jointly shape EMF across diverse arid and semi-arid ecosystems. Comparative studies across multiple dryland systems will further help evaluate the generality and transferability of patterns observed in the Hobq Desert.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated the distinct effects of species richness and phylogenetic diversity on multifunctionality in the desert shrub ecosystem. In the Hobq Desert, species richness proved to be a significantly stronger predictor of EMF than phylogenetic diversity, indicating that species diversity plays a key role in driving shrub ecosystem functioning in this region. In addition, climatic factors, especially changes in annual precipitation, indirectly regulate EMF by influencing species richness. Although the relationship between ecosystem multifunctionality and diversity is intricate and influenced by multiple biotic and environmental factors, the findings of this study highlight the pivotal role of species diversity in sustaining ecosystem functioning, particularly under the pressures of climate change.

This study also demonstrated that species diversity and phylogenetic diversity can jointly enhance ecosystem multifunctionality to some extent, despite phylogenetic diversity occasionally exhibiting a negative effect on EMF. Future research should focus on the distinct contributions of multidimensional biodiversity to ecosystem functioning, particularly the regulatory roles of functional diversity and phylogenetic diversity. Moreover, greater attention is needed on the interactive effects of climate change on biodiversity and EMFs to inform more holistic ecosystem management and conservation strategies.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Poorter, L. et al. Biodiversity and climate determine the functioning of Neotropical forests. Global Ecol. Biogeogr. 26, 1423–1434 (2017).

Tariq, A. et al. Plant root mechanisms and their effects on carbon and nutrient accumulation in desert ecosystems under changes in land use and climate. New. Phytol. 242, 916–934 (2024).

Li, Z. et al. Shallow tillage mitigates plant competition by increasing diversity and altering plant community assembly process. Front Plant. Sci 15:1409493(2024).

Tilman, D., Lehman, C. L. & Thomson, K. T. Plant diversity and ecosystem productivity: theoretical considerations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 94, 1857–1861 (1997).

Grime, J. P. Benefits of plant diversity to ecosystems: immediate, filter and founder effects. J. Ecol. 86, 902–910 (1998).

Wang, S. & Loreau, M. Biodiversity and ecosystem stability across scales in metacommunities. Ecol. Lett. 19, 510–518 (2016).

Yan, P. et al. The essential role of biodiversity in the key axes of ecosystem function. Global Change Biol. 29, 4569–4585 (2023).

Tilman, D. et al. Diversity and productivity in a Long-Term grassland experiment. Science 294, 843–845 (2001).

Tilman, D., Isbell, F. & Cowles, J. M. Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 45, 471–493 (2014).

D’Andrea, R. et al. Reciprocal Inhibition and competitive hierarchy cause negative biodiversity-ecosystem function relationships. Ecol. Lett. 27, e14356 (2024).

Karanth, K. P., Gautam, S., Arekar, K. & Divya, B. Phylogenetic diversity as a measure of biodiversity: pros and cons. J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 116, 53–61 (2019).

Steudel, B. et al. Contrasting biodiversity–ecosystem functioning relationships in phylogenetic and functional diversity. New. Phytol. 212, 409–420 (2016).

Wang, X. et al. Phylogenetic diversity drives soil multifunctionality in arid montane forest-grassland transition zone. Front. Plant. Sci. 15, 1344948 (2024).

Venail, P. et al. Species richness, but not phylogenetic diversity, influences community biomass production and Temporal stability in a re-examination of 16 grassland biodiversity studies. Funct. Ecol. 29, 615–626 (2015).

Hu, Y. et al. Species diversity is a strong predictor of ecosystem multifunctionality under altered precipitation in desert steppes. Ecol. Indic. 137, 108762 (2022).

Manning, P. et al. Redefining ecosystem multifunctionality. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2, 427–436 (2018).

Mori, A. S., Isbell, F. & Cadotte, M. W. Assessing the importance of species and their assemblages for the biodiversity-ecosystem multifunctionality relationship. Ecology 104, e4104 (2023).

Van Der Plas, F. Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning in naturally assembled communities. Biol. Rev. 94, 1220–1245 (2019).

Zhou, G. et al. Stand Spatial structure and microbial diversity are key drivers of soil multifunctionality during secondary succession in degraded karst forests. Sci. Total Environ. 937, 173504 (2024).

Pichon, N. A. et al. Nitrogen availability and plant functional composition modify biodiversity-multifunctionality relationships. Ecol. Lett. 27, e14361 (2024).

Allan, E. et al. Land use intensification alters ecosystem multifunctionality via loss of biodiversity and changes to functional composition. Ecol. Lett. 18, 834–843 (2015).

Jing, X. et al. The links between ecosystem multifunctionality and above- and belowground biodiversity are mediated by climate. Nat. Commun. 6, 8159 (2015).

Liu, Y. R. et al. Identity of biocrust species and microbial communities drive the response of soil multifunctionality to simulated global change. Soil Biol. Biochem. 107, 208–217 (2017).

Zheng, J. et al. Biodiversity and soil pH regulate the recovery of ecosystem multifunctionality during secondary succession of abandoned croplands in Northern China. J. Environ. Manage. 327, 116882 (2023).

Fu, B., Liu, Y. & Meadows, M. E. Ecological restoration for sustainable development in China. Natl. Sci. Rev. 10, nwad033 (2023).

Ren, M., Chen, W. & Wang, H. Ecological policies dominated the ecological restoration over the core regions of Kubuqi desert in recent decades. Remote Sens. 14, 5243 (2022).

Han, Q. et al. Water balance characteristics of the Salix shelterbelt in the Kubuqi desert. Forests 15, 278 (2024).

Chen, P. et al. Ecological restoration intensifies evapotranspiration in the Kubuqi desert. Ecol. Eng. 175, 106504 (2022).

Zhang, L. et al. Effects of grazing disturbance of Spatial distribution pattern and interspecies relationship of two desert shrubs. J. Res. 33, 507–518 (2021).

Jiang, L. M. et al. Different contributions of plant diversity and soil properties to the community stability in the arid desert ecosystem. Front. Plant. Sci. 13, 969852 (2022).

Le Bagousse-Pinguet, Y. et al. Phylogenetic, functional, and taxonomic richness have both positive and negative effects on ecosystem multifunctionality. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 116, 8419–8424 (2019).

Maestre, F. T. & Quero, J. L. It is getting hotter in here: determining and projecting the impacts of global environmental change on drylands. Philos. T R Soc. B. 367, 3062–3075 (2012).

Liu, C. et al. Drought is threatening plant growth and soil nutrients of grassland ecosystems: A meta-analysis. Ecol. Evol. 13, e10092 (2023).

Qian, J. et al. The advantage of afforestation using native tree species to enhance soil quality in degraded forest ecosystems. Sci. Rep. 14, 20022 (2024).

Uddin, M. J. et al. Soil organic carbon dynamics in the agricultural soils of Bangladesh following more than 20 years of land use intensification. J. Environ. Manage. 305, 114427 (2022).

Bogunovic, I., Pereira, P. & Brevik, E. C. Spatial distribution of soil chemical properties in an organic farm in Croatia. Sci. Total Environ. 584–585, 535–545 (2017).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R v4.3.2. Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL (2023). https://www.R-project.org/

Jin, Y. & Qian, H. V. PhyloMaker2: an updated and enlarged R package that can generate very large phylogenies for vascular plants. Plant. Divers. 44, 335–339 (2022).

Xu, S. et al. Ggtree: A serialized data object for visualization of a phylogenetic tree and annotation data. iMeta 1, e56 (2022).

Zhou, Y. et al. Species richness and phylogenetic diversity of seed plants across vegetation zones of Mount kenya, East Africa. Ecol. Evol. 8, 8930–8939 (2018).

Byrnes, J. E. K. et al. Investigating the relationship between biodiversity and ecosystem multifunctionality: challenges and solutions. Methods Ecol. Evol. 5, 111–124 (2014).

Goldstein, A. & Pitkin, E. Kapelner,Adam, Bleich, Justinand Peeking Inside the Black Box: Visualizing Statistical Learning With Plots of Individual Conditional Expectation. J. Comput. Graphical Stat. 24, 44–65 (2015).

Kline, R. B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modelingvol. 1 (Guilford, 2012).

Zhang, S., Chen, Y., Zhou, X. & Zhang, Y. Climate and human impact together drive changes in ecosystem multifunctionality in the drylands of China. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 193, 105163 (2024).

Yang, H. et al. Plant community responses to nitrogen addition and increased precipitation: the importance of water availability and species traits. Global Change Biol. 17, 2936–2944 (2011).

Zuo, X. et al. Observational and experimental evidence for the effect of altered precipitation on desert and steppe communities. Global Ecol. Conserv. 21, e00864 (2020).

Li, D., Miller, J. E. D. & Harrison, S. Climate drives loss of phylogenetic diversity in a grassland community. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116, 19989–19994 (2019).

Eskelinen, A. & Harrison, S. P. Resource colimitation governs plant community responses to altered precipitation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112, 13009–13014 (2015).

Zhu, Y. et al. Increased precipitation attenuates shrub encroachment by facilitating herbaceous growth in a Mongolian grassland. Funct. Ecol. 36, 2356–2366 (2022).

Migliavacca, M. et al. The three major axes of terrestrial ecosystem function. Nature 598, 468–472 (2021).

Wang, X. et al. Spatial variability of soil organic carbon and total nitrogen in desert steppes of china’s Hexi corridor. Front Environ. Sci 9:761313 (2021).

Zhu, X. et al. Changes of soil carbon along precipitation gradients in three typical vegetation types in the Alxa desert region, China. Carbon Balance Manage. 19, 19 (2024).

Medina-Roldán, E. et al. Precipitation controls topsoil nutrient buildup in arid and semiarid ecosystems. Agriculture-london 14, 2364 (2024).

Schmitz, O. J. Species in ecosystems and all that jazz. PLOS Biol. 16, e2006285 (2018).

Schuldt, A. et al. Biodiversity across trophic levels drives multifunctionality in highly diverse forests. Nat. Commun. 9, 2989 (2018).

Craven, D. et al. Multiple facets of biodiversity drive the diversity–stability relationship. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2, 1579–1587 (2018).

Thomsen, M. S. et al. Heterogeneity within and among co-occurring foundation species increases biodiversity. Nat. Commun. 13, 581 (2022).

Loiola, P. P. et al. Invaders among locals: alien species decrease phylogenetic and functional diversity while increasing dissimilarity among native community members. J. Ecol. 106, 2230–2241 (2018).

Larkin, D. J. et al. Evolutionary history shapes grassland productivity through opposing effects on complementarity and selection. Ecology 104, e4129 (2023).

Fox, J. W. & Vasseur, D. A. Character convergence under competition for nutritionally essential resources. Am. Nat. 172, 667–680 (2008).

Cadotte, M. W. Functional traits explain ecosystem function through opposing mechanisms. Ecol. Lett. 20, 989–996 (2017).

Diaz, S. et al. The plant traits that drive ecosystems: evidence from three continents. J. Veg. Sci. 15, 295–304 (2004).

Moreno-Mateos, D. et al. The long-term restoration of ecosystem complexity. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 4, 676–685 (2020).

Hector, A. & Bagchi, R. Biodiversity and ecosystem multifunctionality. Nature 448, 188–190 (2007).

Capmourteres, V. & Anand, M. Conservation value: a review of the concept and its quantification. Ecosphere 7, e01476 (2016).

Bruelheide, H. et al. Global trait–environment relationships of plant communities. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2, 1906–1917 (2018).

Gampe, D. et al. Increasing impact of warm droughts on Northern ecosystem productivity over recent decades. Nat. Clim. Change. 11, 772–779 (2021).

Fang, Z. et al. Global increase in the optimal temperature for the productivity of terrestrial ecosystems. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 1–9 (2024).

García, F. C., Bestion, E. & Warfield, R. Yvon-Durocher, G. Changes in temperature alter the relationship between biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. PNAS 115, 10989–10994 (2018).

Xu, F. W. et al. Seasonality regulates the effects of resource addition on plant diversity and ecosystem functioning in semi-arid grassland. J. Plant. Ecol. 14, 1143–1157 (2021).

Ye, J. S., Reynolds, J. F., Sun, G. J. & Li, F. M. Impacts of increased variability in precipitation and air temperature on net primary productivity of the Tibetan plateau: a modeling analysis. Clim. Change. 119, 321–332 (2013).

Huang, X. et al. Acidification of soil due to forestation at the global scale. Ecol. Manage. 505, 119951 (2022).

Pärtel, M. Local plant diversity patterns and evolutionary history at the regional scale. Ecology 83, 2361–2366 (2002).

Cadotte, M. W. The new diversity: management gains through insights into the functional diversity of communities. J. Appl. Ecol. 48, 1067–1069 (2011).

Laliberté, E. & Legendre, P. A distance-based framework for measuring functional diversity from multiple traits. Ecology 91, 299–305 (2010).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Jirong Qiao for her valuable assistance in the grammatical proofreading of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region “Unveiling the List of Commanders” Project (2024JBGS0019), the Science and Technology Highland Construction Project (CAFYBB2024ZA007-02), the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region “Unveiling the List of Commanders” Project (2024JBGS0021), the Scientific Research Capacity Enhancement Project of Inner Mongolia Academy of Forestry Sciences (2024NLTS01 and 2024NLTS03), the Key Special Project for the Action of “Revitalizing Inner Mongolia through Science and Technology” (2022EEDSKJXM003), and the Natural Science Foundation of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (2024QN03025).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zihao Li: Conceptualization, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing. Zhuofan Li: Investigation, Data Curation, Project administration. Xiaowei Gao: Investigation, Data Curation. Guangyu Hong: Investigation, Data Curation. Xiaojiang Wang: Resources, Supervision. Long Hai: Writing - Review & Editing, Funding acquisition. Runhong Gao: Writing - Review & Editing. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Z., Li, Z., Gao, X. et al. Species richness is an important mediator of multifunctionality changes in Hobq desert shrub ecosystem. Sci Rep 15, 29152 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14521-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14521-y