Abstract

While overall survival has been extensively studied in amyloidosis, less attention has been given to patient-centered measures that integrate morbidity and mortality. Days Alive and Out of Hospital (DAOH) is an emerging metric that captures both aspects and has potential utility in the evaluation of disease impact.To describe DAOH in patients with wild-type transthyretin amyloidosis (ATTRwt) and explore factors associated with DAOH.Retrospective cohort study used the Institutional Registry of Amyloidosis database of the Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires (2015–2023). All patients with ATTRwt amyloidosis enrolled in the registry and affiliated with the health maintenance organization of the hospital were included. DAOH were estimated at 1, 3 and 5 years. Associations between DAOH and risk factors were evaluated.61 cases were included. The median age was 83 years, and 89% were male. Median (IQR) DAOH were 365 (353–365), 998 (553–1094) and 1314 (740–1769) days for 1, 3, and 5 years, respectively. Atrial fibrillation was associated with lower DAOH.DAOH is a simple, reproducible metric. Our findings highlight the importance of considering morbidity, not just mortality, in patients with ATTRwt amyloidosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Amyloidosis is a heterogeneous group of rare systemic disorders caused by the extracellular deposition of misfolded protein fibrils, which progressively accumulate in tissues and organs, leading to dysfunction. The clinical presentation varies widely depending on the type of precursor protein and the organ involvement1. The most common types include light-chain amyloidosis (AL), hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis (ATTRv), and wild-type transthyretin amyloidosis (ATTRwt)2.

ATTRwt amyloidosis is increasingly recognized as a cause of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) in older adults, particularly in men over 65 years3. It is characterized by progressive myocardial infiltration by transthyretin-derived fibrils, resulting in ventricular wall thickening, diastolic dysfunction, and restrictive cardiomyopathy. Patients often present with signs of heart failure and arrhythmias, particularly atrial fibrillation4. Despite improvements in diagnostic tools, diagnosis is frequently delayed until advanced stages, when cardiac involvement is already significant and prognosis is poor5,6,7.

Epidemiological studies suggest that ATTRwt amyloidosis may be underdiagnosed. Its prevalence among patients with HFpEF ranges between 5 and 16%8,9,10. Despite advancements in diagnostic techniques and therapeutic options, survival remains limited, with a median overall survival ranging from 3 to over 5 years11,12. Additionally, patients with ATTRwt amyloidosis experience significant morbidity, with hospitalization rates estimated between 61 and 78% within the first-year post-diagnosis13.

Traditional outcomes in amyloidosis studies, such as survival or hospitalization, may not fully capture the complexity of disease. In this context “Days Alive and Out of Hospital” (DAOH) has emerged as a patient-centered outcome measure designed to assess both mortality and morbidity by measuring the number of days a patient is alive and not hospitalized within a defined follow-up period14,15. This outcome has been used in perioperative medicine and cardiovascular trials, but its application in amyloidosis remains less explored14,15,16,17.

The aim of this study is to evaluate DAOH as a comprehensive measure of disease impact in patients with ATTRwt amyloidosis and to identify clinical variables associated with lower DAOH, focusing on atrial fibrillation, heart failure hospitalizations and National Center of Amyloidosis (NAC) staging.

Methods

This is a retrospective closed cohort study using a hospital-based population sample from the Institutional Amyloidosis Registry database from Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires. The registry, established in 2010 by the Amyloidosis Study Group, includes all patients diagnosed with any type of amyloidosis who receive care at the Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires. Additionally, the hospital has its own Health Maintenance Organization (HMO), which provides integrated care across all settings and ensures complete clinical follow-up through a unified electronic health record system.

Study population

We included adult patients (≥ 18 years) diagnosed with wild-type transthyretin amyloidosis (ATTRwt) between January 1, 2015, and December 31, 2023. All patients were affiliated with the hospital’s Health Maintenance Organization (HMO), ensuring complete inpatient and outpatient follow-up through a unified electronic health record system. Patients were excluded if they had other forms of amyloidosis (e.g., hereditary ATTR or AL amyloidosis).

Diagnosis of ATTRwt amyloidosis was established based on a compatible clinical presentation—defined as septal wall thickness greater than 12 mm on echocardiography along with at least one clinical “red flag” (e.g., bilateral carpal tunnel syndrome, biceps tendon rupture, or heart failure in ≥ 65 years). This suspicion was confirmed by a positive bone scintigraphy (Perugini Grade 2 or 3), absence of monoclonal protein (normal kappa/lambda free light chain ratio), and negative TTR gene mutation testing18. Baseline disease severity was also assessed using the NAC staging system, which combines NT-proBNP and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). Patients were classified as Stage I if NT-proBNP was < 3000 pg/mL and eGFR ≥ 45 mL/min/1.73m2, Stage II if only one of the two markers was abnormal, and Stage III if both thresholds were exceeded12.

Follow-up

All included patients were followed from the date of diagnosis of ATTRwt amyloidosis until death or a predefined follow-up interval of 1, 3, or 5 years (corresponding to 365, 1095, or 1825 days), whichever occurred first.mPatients who died before completing the predefined follow-up intervals were included in the DAOH analyses. In such cases, days not alive were subtracted from the potential follow-up time, as per DAOH methodology. In contrast, patients who were still alive at the end of the study period but had not yet completed the full follow-up duration—due to recent diagnosis—were excluded from the corresponding DAOH analyses. This is because DAOH cannot be reliably calculated in survivors without complete follow-up data. There were no exclusions due to administrative censoring, changes in insurance coverage, or missing data.

Outcomes

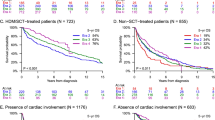

The primary outcome was DAOH at 1, 3, and 5 years. For the estimation, the following measures were considered: 1) Potential follow-up time: From the date of diagnosis to 365 (DAOH at 1 year) or 1095 (DAOH at 3 years) or 1826 days (DAOH at 5 years); 2) Hospital length of stay during the potential follow-up time; 3) Number of days of death: Total days from the date of death until the end of potential follow-up time. Then, the days of hospitalization and/or days death were subtracted from the potential follow-up time. An example is shown in Fig. 1.

Examples of DAOH calculations. Caption: Two examples of DAOH calculations for a potential follow-up time of 365 days (1-year DAOH) are shown. Figure A shows the DAOH for a patient who required two hospitalizations during the potential follow-up time. Figure B shows the DAOH for a patient who required two hospitalizations and also died during the potential follow-up time.

Secondary outcome was the DAOH considering, in addition to the days of hospitalization, the days that the patient visited the hospital for outpatient care, either scheduled or on call, and left before 24 h. Additionally, we explored the association between DAOH atrial fibrillation, prior hospitalization for heart failure and NAC stage. All data were extracted from the Institutional Amyloidosis Registry and by review of the electronic medical records. This was not missing data.

Statistical analysis

Numerical variables were reported as medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) or means and standard deviations (SD) as appropriate. Categorical variables were presented as absolute and relative frequencies. The association between DAOH and clinical variables was assessed using the Wilcoxon test. We used the Kruskal–Wallis test to compare DAOH across NAC stages (I, II, III) at 1, 3, and 5 years. Analyses were conducted using Stata 16 (StataCorp LLC).

For assistance with writing, and editing, we used ChatGPT (Chat Generative Pre-trained Transformer), developed by OpenAI. Specifically, we employed the GPT-4o version, accessed via the official web platform https://chat.openai.com.

Ethical approval and consent

This study protocol relied on a limited, secondary data set and was approved by the Comité de Ética de Protocolos de Investigación of the Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires (IRB) under number 7980, which waived the requirement for informed consent. This research was conducted in compliance with ethical principles consistent with national and international regulatory standards for human health research, in accordance with National Ministerial Resolution No. 1480/2011, Law 3301/09 of the Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, the Declaration of Helsinki, and in compliance with ICH E6 Good Clinical Practice Standards. This study is retrospective in nature, and the requirement for informed consent was waived by the Comité de Ética de Protocolos de Investigación of the Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Results

Participants

Among 114 eligible patients, 61 met the inclusion criteria. Of the 61 subjects, the total was analysed for DAOH at 1 year, while 35 met the follow-up criteria for DAOH at 3 years, and 15 for DAOH at 5 years.

Baseline characteristics

Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of the patients included in the study. The median age was 83 years (IQR 80–87), and 89% (n = 54) were male. Atrial fibrillation was present in 52% (n = 32) of the cohort, while 72% (n = 44) had a diagnosis of congestive heart failure (CHF), and 39% (n = 24) and had prior hospitalizations due to CHF. The median Charlson Comorbidity Index score was 5 (IQR 4–7). The ejection fraction was preserved in most patients. According to the revised National Amyloidosis Centre (NAC) staging, 38% (n = 23) of patients were classified as Stage I, 42% (n = 26) as Stage II, and 20% (n = 12) as Stage III.

Regarding therapeutic interventions, 59 patients (97%) received supportive care for congestive heart failure and, 33 (54%) specific pharmacological treatment for amyloidosis, of which 30 (91%) received doxycycline-ursodeoxycholic acid and 3 (9%) tafamidis. Tafamidis was initiated as part of standard clinical care after regulatory approval, at a dose of 61 mg.

Main results

Table 2 summarizes DAOH for the cohort at different follow-up intervals. The median DAOH was 365 (353–365) days at 1 year, 998 (553–1094) days at 3 years, and 1314 (740–1769) days at 5 years. When outpatient visits were included, DAOH estimates declined significantly, suggesting persistent healthcare engagement beyond hospitalization.

Table 3 presents DAOH at 1, 3, and 5 years according to comorbidities and NAC staging. Atrial fibrillation was associated with lower DAOH at all time points, reaching statistical significance when outpatient care was considered. Prior hospitalizations for heart failure were associated with lower DAOH at 1 year but did not reach statistical significance at longer follow-ups. DAOH was also analyzed according to NAC stage. At 1 and 5 years, statistically significant differences were observed across stages when outpatient visits were included, while no differences were found at 3 years.

Thirty-one patients (51%) had died at 1 year, twenty-five (71%) at 3 years, and ten (67%) at 5 years of follow-up. Table 4 shows a complementary analysis comparing healthcare utilization among patients who were alive versus deceased at each time point. Deceased patients consistently showed more hospitalizations and longer hospital stays, particularly at 1 and 3 years. No significant differences were observed at 5 years.

Discussion

Our study introduces DAOH as a meaningful outcome metric in ATTRwt amyloidosis. Unlike traditional survival endpoints, DAOH captures both morbidity and mortality, offering a more comprehensive assessment of disease impact. The observed association between atrial fibrillation and reduced DAOH aligns with prior studies linking atrial fibrillation to worse cardiovascular outcomes in amyloidosis19.

Our findings underscore the significant healthcare needs of patients with ATTRwt amyloidosis. While patients achieved a median of 365 days out of the hospital in the first year and 998 days in the third year when considering only hospital stays longer than 24 h, when outpatient visits were considered, there was a notable decrease in DAOH. This highlights that while patients may evade hospitalization for certain periods, their persistent need for healthcare underscores the importance of comprehensive and coordinated care.

To date, we have identified only one previous study that utilized DAOH as a measure of health outcomes in patients with amyloidosis. Rubin et al. examined DAOH among patients with cardiac involvement due to AL and ATTR amyloidosis, starting from the time of their first hospitalization and excluding those who had never been hospitalized16. Consequently, their overall results are lower than those reported in our study. This comparison highlights the potential of DAOH as a valuable metric for assessing patient outcomes across different amyloidosis subtypes and healthcare settings.

Although atrial fibrillation was associated with lower DAOH at all timepoints, statistical significance was only observed when outpatient care was included in the calculation. When considering hospitalizations alone, a non-significant trend was observed at 1 and 3 years, with no apparent differences at 5 years. Since DAOH explicitly incorporates mortality—by subtracting days not alive from the potential follow-up time—this pattern is unlikely to reflect survivor bias. A more plausible explanation is the progressive loss of statistical power over time, as fewer patients contribute to DAOH estimates at longer follow-up intervals. This is because only patients diagnosed early enough can reach the 3- or 5-year timepoints. Consequently, the reduction in sample size may obscure persistent associations in the long term. Similarly, although we observed a trend toward lower DAOH in patients with more advanced NAC stages, particularly at 1 year, these differences became less apparent over time. At 5 years, the small and unbalanced number of patients with complete follow-up in each NAC category substantially limits both statistical power and interpretability. Accordingly, results from the 5-year analysis should be considered exploratory.

The low frequency of tafamidis use in our cohort could reflect barriers such as delayed drug availability and cost limitations. Additionally, since our analysis focused exclusively on first-line treatments, tafamidis initiated later in the disease course may not have been captured, which could have further contributed to the observed low prevalence.

Finally, our findings show that deceased patients experienced a higher number of hospitalizations and longer cumulative hospital stays compared to survivors, particularly during the early years following diagnosis. This suggests that the lower DAOH observed in this subgroup is not solely explained by reduced survival time but also by increased healthcare utilization in the period leading up to death. This pattern aligns with the so-called “revolving door” phenomenon described in older adults with chronic illnesses, where frequent hospital admissions precede death and reflect progressive clinical decline. Although these results should be interpreted cautiously due to the small sample size in long-term analyses, they support the value of DAOH as a metric that captures both disease burden and healthcare intensity.

One limitation of our study is its retrospective design and single-centre setting, which may affect generalizability. However, the standardized and systematic use of the electronic medical record in our hospital minimizes this risk. Importantly, there were no losses to follow-up for patients enrolled in the registry, ensuring robust data collection.

Conclusions

DAOH is a novel and practical measure of healthcare utilization. Its implementation in clinical trials and routine practice could provide a more holistic understanding of disease progression and treatment impact. Future studies should validate DAOH in larger, multicentre cohorts and explore its predictive value for long-term clinical outcomes.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to our commitment to data confidentiality. Our study focuses on patients with a rare disease (ATTRwt amyloidosis) and has a small sample size in an 8-year cohort. The data include information that could reveal identifiable treatment patterns, as well as data on sex, age, solid organ transplant, and mortality, which could allow identification of individual patients, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Gillmore, J. D. & Hawkins, P. N. Pathophysiology and treatment of systemic amyloidosis. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 9, 574–586 (2013).

Ravichandran, S., Lachmann, H. J. & Wechalekar, A. D. Epidemiologic and survival trends in amyloidosis, 1987–2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 1567–1568 (2020).

Gilstrap, L. G. et al. Epidemiology of cardiac amyloidosis-associated heart failure hospitalizations among fee-for-service medicare beneficiaries in the United States. Circ. Heart Fail. 12, e005407 (2019).

García-Pavía, P., Tomé-Esteban, M. T. & Rapezzi, C. Amyloidosis. Also a heart disease. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 64, 797–808 (2011).

Maurer, M. S. et al. Expert consensus recommendations for the suspicion and diagnosis of transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis. Circ. Heart Fail. 12, e006075 (2019).

Rozenbaum, M. H. et al. Impact of delayed diagnosis and misdiagnosis for patients with transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy (ATTR-CM): A targeted literature review. Cardiol. Ther. 10, 141–159 (2021).

Gillmore, J. D. et al. Nonbiopsy diagnosis of cardiac transthyretin amyloidosis. Circulation 133, 2404–2412 (2016).

Magdi, M. et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of transthyretin amyloidosis in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Dis. 12, 102–111 (2022).

AbouEzzeddine, O. F. et al. Prevalence of transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. JAMA Cardiol. 6, 1267–1274 (2021).

García-Pavía, P. et al. Prevalence of transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: The PRACTICA study. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. (Engl. Ed). 78, 301–310 (2025).

Chacko, L. et al. Echocardiographic phenotype and prognosis in transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis. Eur. Heart J. 41, 1439–1447 (2020).

Gillmore, J. D. et al. A new staging system for cardiac transthyretin amyloidosis. Eur. Heart J. 39, 2799–2806 (2018).

Re Kawada, T. et al. Incidence rate of hospitalization and mortality in the first year following initial diagnosis of cardiac amyloidosis in the US claims databases. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 37(8), 1275–1281 (2022).

Fanaroff, A. C. et al. Days alive and out of hospital: Exploring a patient-centered, pragmatic outcome in a clinical trial of patients with acute coronary syndromes. Circ Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcome. 11, e004755 (2018).

Ariti, C. A. et al. Days alive and out of hospital and the patient journey in patients with heart failure: Insights from the candesartan in heart failure: assessment of reduction in mortality and morbidity (CHARM) program. Am. Heart J. 162, 900–906 (2011).

Rubin, J., Teruya, S., Helmke, S., De Los Santos, J. & Alvarez MS Maurer, J. Days alive and outside of hospital from diagnosis of transthyretin vs light chain cardiac amyloidosis. Amyloid 26, 4–5 (2019).

Moonesinghe, S. R. et al. Systematic review and consensus definitions for the standardised endpoints in perioperative medicine initiative: Patient-centred outcomes. Br. J. Anaesth. 123, 664–670 (2019).

Garcia-Pavia, P. et al. Diagnosis and treatment of cardiac amyloidosis: A position statement of the ESC working group on myocardial and pericardial diseases. Eur. Heart J. 42, 1554–1568 (2021).

Chamberlain, A. M., Redfield, M. M., Alonso, A., Weston, S. A. & Roger, V. L. Atrial fibrillation and mortality in heart failure: a community study. Circ. Heart Fail. 4, 740–746 (2011).

Acknowledgements

Elsa M. Nucifora, Patricia B. Sorroche, Erika B. Brulc, María S. Sáez, Diego Pérez de Arenaza, Eugenia Villanueva and Santiago Decotto, for their contribution in the Institutional Amyloidosis Registry.

Funding

This work was supported by Pfizer (Grant number 88792339).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MV contributed to the conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, validation, writing -original draft, review and editing. T E contributed to the conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, validation, writing -original draft, review and editing. MAA contributed to the conceptualization, investigation, validation, writing review and editing. AS contributed to investigation, formal analysis, writing -original draft. FEH contributed to investigation, formal analysis, writing -original draft. MLP-M contributed to conceptualization, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, supervision, validation, writing review and editing. MC contributed to conceptualization, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, supervision, validation, writing -original draft, review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study protocol relied on a limited, secondary data set and was approved by the Comité de Ética de Protocolos de Investigación of the Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires (IRB) under number 7980, which waived the requirement for informed consent. This research was conducted in compliance with ethical principles consistent with national and international regulatory standards for human health research, in accordance with National Ministerial Resolution No. 1480/2011, Law 3301/09 of the Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, the Declaration of Helsinki, and in compliance with ICH E6 Good Clinical Practice Standards. This study is retrospective in nature, and the requirement for informed consent was waived by the Comité de Ética de Protocolos de Investigación of the Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vaena, M., Aguirre, M.A., Epstein, T. et al. Days alive and out of hospital in patients with wild type transthyretin amyloidosis: cohort study. Sci Rep 15, 30396 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14526-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14526-7