Abstract

Sex differences in performance and pacing in triathlon have been studied for IRONMAN triathlons (3.8 km swimming, 180 km cycling and 42.195 km of running) and ultra-triathlons (i.e. Double-, Triple-, Quintuple- and Deca Iron ultra-triathlons) corresponding to 2x, 3x, 5x and 10x the IRONMAN triathlon distance. However, no study has to date investigated the sex difference in performance and pacing in the longest triathlon held in history, the Triple Deca Iron ultra-triathlon covering 114 km of swimming, 5,400 km of cycling and 1,266 km of running. A total of 14 triathletes (10 men and four women) competed in the 2024 Triple Deca Ultra Triathlon in Desenzano del Garda, with four men and three women officially finishing the race within the time limit. The data were analyzed to investigate performance differences across disciplines (i.e. swimming, cycling, and running), pacing strategies and sex differences. Variability was assessed using each discipline’s coefficient of variation (CV). The relation-ships between CV and overall rankings were examined using linear regression analysis. Men were faster in swimming (12.4%), cycling (24.8%) and running (8.5%). Cycling showed the greatest pacing variability, while running exhibited steadier pacing, with more consistent athletes performing better overall, reflecting the unique endurance challenges of this segment. Overall, men were faster than women in all split disciplines, with the highest sex difference in cycling and the smallest in running. The analysis revealed significant differences in both cycling and running times among athletes. The variability in cycling times indicates diverse pacing strategies and endurance levels, while the running times further highlight the individual performance dynamics of the athletes. The results illustrate how variability in pacing affects cumulative performance and final rankings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There is an ongoing debate about whether women would be able to outperform men in ultra-endurance performance1. While women have lower muscle strength, a smaller heart and blood volume, and a lower hematocrit, they exhibit a greater muscle oxidative capacity and a better lipid metabolism2,3,4,5. These physiological differences may account for women’s superior performance in endurance events, which rely heavily on aerobic metabolism, compared to shorter events that are more dependent on anaerobic metabolism. In some instances, women were able to win ultra-endurance races ahead of all men6. Large studies with data analyses from ultra-endurance races have shown, however, that there is a gap between women and men, where men were faster but women are able to reduce the gap to men1,7,8.

For example, in trail-running of different race distances, the sex difference decreased with increasing race distance, but the fastest men were always faster than the fastest women7. However, the kind of the endurance discipline might be a decisive factor about whether women can outperform men. In ultra-cycling distances from 100, 200, 400 and 500 miles, men were faster than women in 100- and 200-mile races, but not in 400- and 500-mile races9. While women competing in ultra-endurance events were able to keep up with men in cycling but not in running, the question of the role of sex on performance in another sport discipline such as swimming remains. Indeed, a comprehensive analysis of successful finishers of the ‘Triple Crown of Open Water Swimming’ (Catalina Channel Swim, English Channel Swim, and Manhattan Island Marathon Swim) from 1875 to 2017 showed that women were ~ 0.06 km/h faster than men10. Potential explanations for the better performance of women in open-water long-distance swimming could be the rather low water temperatures and female body characteristics such as a better buoyancy and a higher body fat percentage, besides a better fat oxidation3,11,12. Regarding the sex difference in cycling where women were able to keep up with men in 400- and 500-mile races, lower body mass and better fat oxidation might be decisive for female performance3,12.

Triathlon combines the three disciplines of swimming, cycling, and running in that order, and provides an optimal model to study the role of sex on performance during different exercise modes. Sex differences in triathlon races have been investigated for different race distances such as the Olympic distance12,13, or the IRONMAN distance12,14 triathlon.

In general, the sex difference in both Olympic and IRONMAN distances narrowed over the years and varied by both the discipline itself and the length of a discipline. In elite Olympic distance triathletes, the sex difference in running performance was greater in the Olympic distance (~ 14%) than in IRONMAN distance (~ 7%) triathlon. For non-elite IRONMAN triathletes, the sex difference in swimming (~ 12%) was smaller than in cycling (~ 15%) and running (~ 18%)15. At longer distances, a study investigating sex differences from the IRONMAN to the Double Deca Iron ultra-triathlon (76 km swimming, 3,600 km cycling, 844 km running) showed that the sex differences for the three fastest finishers ever for swimming, cycling, running and overall race times for all distances from the IRONMAN to the Double Deca Iron ultra-triathlon were ~ 27.0%, ~ 24.3%, ~ 24.5%, and ~ 24.0%, respectively. Although women reduced the sex difference in the shorter long-distance triathlon distances such as the IRONMAN distance, the sex gap widened in the longer triathlon distances such as the Double and the Triple Iron ultra-triathlon16.

Pacing is also an important aspect of endurance performance in general and also of ultra-triathlon performance17. A study investigating pacing in ultra-triathlons, including Double Iron, Triple Iron, Quintuple Iron and Deca Iron ultra-triathlons held between 1985 and 2018, showed that there were differences in pacing between sexes and at different race distances18. Regarding the race distance, athletes invested less time in swimming and cycling in the longer race distances, but more time in running as the race distance increased18. Regarding the sex, women invested more time in cycling and less time in running in both Double and Triple Iron ultra-triathlons18.

The question now arises as to whether women might be able to outperform men in even longer triathlon distances and whether and where differences in pacing between women and men exist. In the autumn of 2024, the longest official triathlon in history was held as a race with the Triple Deca Iron ultra-triathlon covering 114 km swimming, 5,400 km cycling, and 1,266 km running (www.ultratriathlonitaly.com/). The objective of this study was to analyze the race with the first aim of a potential sex difference in performance and the second aim of a potential sex difference in pacing. Although one might assume that women might be able to outperform men in even longer ultra-distances, our hypotheses were that (i) men would be faster in all three split disciplines and (ii) there would also be a sex difference in pacing in that men will exhibit more pacing variability than women.

Method

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kanton St. Gallen, Switzerland, with a waiver of the requirement for informed consent of the participants as the study involved the analysis of publicly available data (EKSG 01/06/2010). The study was conducted in accordance with the recognized ethical standards according to the Declaration of Helsinki adopted in 1964 and revised in 2013.

Competition characteristics

The Triple Deca Iron ultra-triathlon started on September 1, 2024 with a 114 km swim in a 50 m pool ‘I Borghi di Lugana’ south of Desenzano at Lake Garda in Northern Italy. The race was held for the first time in history. During swimming, laps were recorded electronically and manually. Due to a malfunction in the electronic chip system during swimming, the manual records were used. Each swimmer had a personal lap counter writing down the time for each 100 m. After the swim, the athletes changed in transition zone 1 at the swimming pool to the cycling split and had to make a transfer by cycling and supported by their crew to the ‘Parco Le Ninfee’, where the cycling course officially started. The athletes had to ride a transfer of ~ 4 km to the cycling course, where they had to complete a total of 782 laps of ~ 7 km. The cycling course was described as 95% flat, but the athletes had to cover an altitude of ~ 1,000 m per IRONMAN distance, resulting in ~ 30,000 m of altitude for the 5,400 km in cycling. After the last cycling lap, the athletes had to make the transfer back to ‘Parco Le Ninfee’ to start the run. The run course started immediately near the finish of the cycling course at the pool of the ‘Parco Le Ninfee’. The run course was mere flat, on grass, dirt, and sand. They had to complete 1,186 running laps of 1.067 km to achieve the distance of 1,266 running km. The athletes were allowed to be supported by their own crew in providing nutrition and equipment in all split disciplines. Nutrition was also provided by the organizer. Support crews were not allowed to pace the athletes. Drafting was forbidden in cycling. At the cycling course, the athletes had to build up a tent for their crew and to make rests. The same was then at the running course. For swimming, the lap times were recorded manually and the final swim time was provided. Lap times in cycling and running were recorded electronically using a chip system (www.raceresult.com/).

Participants

A total of 14 triathletes (10 men and 4 women) signed in for the Triple Deca Iron ultra-triathlon. Upon the start of the race, one man did not start. From the remaining nine men, five dropped out during the swim. Of the four women, one also dropped out during the swim. The remaining four men and three women finished the race within the time limit.

Data set and data preparation

The race data with split times and lap times for swimming, cycling, and running were obtained from the official race website of the ‘Ultra Triathlon Italy’ (www.ultratriathlonitaly.com/). The split times for swimming, cycling, and running were recorded for each athlete.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed to investigate performance differences across disciplines (swimming, cycling, and running), pacing strategies and sex differences. Descriptive statistics, including means and standard deviations, were computed for overall performance and segment times. Variability was assessed using the coefficient of variation (CV) of each discipline. Inferential statistical methods were applied to identify significant differences. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used for comparisons between individual athletes, and Mann-Whitney U tests were performed to examine sex differences in performance times and consistency. Relationships between CV and overall rankings were explored using linear regression analysis. All analyses were performed using statistical software (IBM, SPSS v.26), with the significance level set at <0.05. Plots were created using Python libraries, primarily Matplotlib for visualization and Pandas for data organization. Boxplots, scatter plots and bar charts were generated to illustrate performance metrics, variability, and group.

Results

Performance breakdown in swimming, cycling, running, and overall times

Figure 1 present a comprehensive summary of the cumulative performance times in an ultra-triathlon, broken down into swimming, cycling, and running split times, and overall race times. The swimming split times (Fig. 1A) ranged from 67.98 h (1st man in swimming) to 98.47 h (4th man in swimming) in men; for the women, 94.46 h (1st women in swimming) and 95.78 h (3rd women in swimming). The cycling split (Fig. 1B) showed the greatest variability, with times ranging from 400.73 h (1st man in cycling) to 446.95 h (4th man in cycling) for men; for the women, ranging between 443.75 h (1st women in cycling) and 535.90 h (3rd women in cycling). This reflects significant differences in cycling endurance among participants. In the running split (Fig. 1C), the 1 st placed woman displayed a consistent pacing, completing it in 403.59 h, while the 3rd placed woman recorded a longer time of 433.88 h. For the men, the 1 st concluded in 362.29 h and the 4th in 408.57 h. Overall race times (Fig. 1D) highlight the 1 st placed man in cycling and running as the fastest overall finisher, completing the event in 862.59 h, followed by the 2nd (887.96 h), 3rd (904.52 h) and 4th (926.65 h) men, then the 1 st, 2nd, and 3rd women.

The mean times for men and women across swimming, cycling, and running revealed consistent sex differences. In swimming, men averaged 84.9 h, while women averaged 95.4 h, with an absolute difference of 10.5 h (12.4%). In cycling, men averaged 419.5 h, and women averaged 523.6 h, showing the largest sex difference of 104.1 h (24.8%). In running, men recorded an average time of 387.0 h, compared to 420.0 h for women, resulting in an absolute sex difference of 33.0 h (8.5%).

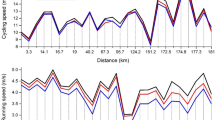

The distribution of the cycling hours (Fig. 2A) among the participants highlights notable performance trends. The boxplot for the cycling hours indicates that the 1 st placed man demonstrates a relatively consistent performance, with a median time comparable to that of the 2nd placed man and the 3rd placed man. However, the 1 st placed man exhibits slightly less variability compared to participants such as the 1 st placed woman and 3rd placed woman, whose distributions display wider interquartile ranges and outliers, reflecting greater fluctuations in cycling performance. Similarly, the run hours boxplot (Fig. 2B) highlights that the 1 st placed male runner maintained a steady performance, with a median time slightly below that of the 2nd placed woman and 1 st placed woman. The variability of the 1 st placed male runner’s performance remains moderate compared to others, with participants like the 3rd placed woman and the 1 st placed woman again showing broader distributions and outliers, suggesting more variability in their running segments

Table 1 summarizes the number of laps (N), minimum and maximum values per lap, mean, and standard deviation for cycling and running lap times. For the cycling split, the mean time based on 5,476 laps was 14:02:38:11 ± 5:14:39:37 dd: hh: mm: ss, ranging from a minimum of 13:17:46:25 dd: hh: mm: ss to a maximum of 27:01:46:00 dd: hh: mm: ss. Men completed the cycling split on average faster compared to women. Table 1 presents the lap times for both cycling and running splits across different participant groups: For the total sample, the average cycling split time was 14 days, 2 h and 38 min and the average running split time was 32 days, 0 h, and 47 min, with both segments exhibiting substantial variation as reflected by the high standard deviations. When broken down by sex, men had slightly faster average split times than women in both cycling (13 days, 3 h vs. 15 days, 9 h) and running splits (30 days, 1 h vs. 34 days, 15 h). Among men, the 1 st placed participant had the fastest split times in both cycling (13 days, 12 h) and running (30 days, 3 h) segments, with progressively slower times observed in subsequent ranks. Similarly, the 1 st placed woman had faster average times (14 days, 6 h for cycling and 32 days, 10 h for running) than their lower-ranked counterparts. A notable trend was the higher variability in split times for women, especially in the 3rd placed group, where the standard deviation was particularly high, indicating a wider performance spread. Overall, these results highlight the performance differences across sexes and ranks, as well as the considerable variability in split times within each group.

Group comparisons

The Kruskal-Wallis test revealed a statistically significant difference in cycling time (Fig. 3A) across athletes (H(2) = 9.73, p =.032). Also, statistically significant differences in running time (Fig. 3B) across the categories of athletes were noted (H(2) = 20.45, p <.001).

A significant difference in cycling time was observed between sex categories (H(1) = 183.417, p <.001; Fig. 4A), indicating a distinct performance gap. Similarly, running time differed significantly between sex categories (H(1) = 1318.130, p <.001; Fig. 4B), further reinforcing the influence of sex-related physiological and biomechanical factors on endurance performance.

Figure 5 illustrates the CV for cycling and running lap times across participants, highlighting their consistency in performance. Lower CV values reflect a greater consistency, while higher values indicate a greater variability in performance. Across all participants, the CV for cycling times was consistently higher than for running times, suggesting that cycling performance exhibited a greater variability than running. Among the athletes, the 3rd placed woman overall demonstrated the most consistent performance with the lowest combined CV. In contrast, the 4th placed man overall showed the highest combined CV, indicating the least consistent performance. These trends suggest that consistency in both segments, particularly in cycling, may contribute significantly to overall competitive performance.

The analysis of the relationship between the CV and rank revealed a negative correlation, where lower CV values, indicating a higher consistency, were associated with better rankings (Fig. 6A). The 1 st placed man overall had one of the lowest combined CVs (~ 25.84%), while the 4th placed man overall exhibited the highest combined CV (~ 29.30%). Cycling performance showed greater variability than running, as cycling CVs were consistently higher across participants. Athletes with lower cycling CVs, such as the 3rd placed woman, demonstrated improved rankings despite not achieving top positions overall. Overall, consistent performance across segments positively impacted competitive standings in the ultra-triathlon event. A linear regression analysis was conducted to evaluate the relationship between the combined CV and the rank in the ultra-triathlon event (Fig. 6B). The model revealed a slightly negative relationship (=−0.247), indicating that lower CV values (higher consistency) were associated with better rankings. However, this relationship was not statistically significant (=0.75), likely due to the small sample size (=7), which limits the statistical power. The regression plot illustrated the trend showing the variability of rank as a function of CV, but additional data and further analysis would be required to confirm this relationship.

Relationship between participant rank and combined coefficient of variation in cycling and running. (A) Correlation between rank and combined coefficient of variation. The scatter plot shows the relationship between participant rank (y-axis) and their combined coefficient of variation (%) for cycling and running (x-axis). (B) Regression analysis: rank vs. combined coefficient of variation. The scatter plot illustrates the relationship between participant rank (y-axis) and their combined coefficient of variation (%) for cycling and running (x-axis), with a regression line included.

Discussion

This study investigated the sex differences in split and overall performances as well as the sex differences in cycling and running performance in the longest ultra-triathlon in history with the hypotheses that sex differences would exist. The main findings were (i) men were faster than women in all split disciplines, with the highest sex difference in cycling and the smallest in running and (ii) cycling showed the greatest pacing variability, while running exhibited steadier pacing, with more consistent athletes performing better overall.

Sex differences in split times

The analysis demonstrated significant differences in the split times for swimming, cycling, and running between women and men. Men consistently achieved faster times in all three split disciplines, which can be attributed to differences in both endurance performance and pacing strategies. The sex differences were 12.4% in swimming, 24.8% in cycling and 8.5% in running. Overall, women had higher mean times in all segments, with the cycling displaying the most significant variation in absolute and percentage terms. Therefore, we can confirm our hypothesis that men were faster than women. Men were faster than women even though this was the longest triathlon distance ever although it was argued that women might be faster than men in ultra-long distances. This observation is consistent with recent research by Hunter and Senefeld19, who found that men outperformed women in many physical capacities such as speed, strength, and power, particularly after male puberty. Furthermore, there is a consensus that these sex differences are due to anatomical and physiological differences20.

Regarding sex differences in triathlon races, among the top ten IRONMAN triathletes who participated in IRONMAN Hawaii between 1981 and 2007, men were faster than women, with sex differences of 9.8 ± 2.9% in swimming, 12.7 ± 2.0% in cycling and 13.3 ± 3.1% in running14. The sex differences between IRONMAN and Triple Deca Iron ultra-triathletes might be due to the length of the event. A study investigating the sex difference in swimming (7.8 km), cycling (360 km) and running (84 km) of 1,591 men and 155 women finishing a Double Iron ultra-triathlon between 1985 and 2012 showed that men were 5.1 ± 5.0% faster in swimming, 8.3 ± 3.5% faster in cycling and 4.2 ± 3.4% faster in running21. It seems that already increasing to two times the classical IRONMAN distance showed that men were considerably faster in cycling and the sex difference was smallest in running.

It is a general belief in science that men are faster than women in endurance sports1,22 where this sex difference is mainly due to biological differences1,22,23. An important aspect regarding triathletes and specialists for single endurance disciplines is the fact that ultra-endurance triathletes are not similar to ultra-endurance swimmers24, ultra-endurance cyclists25 or ultra-endurance runners26 regarding anthropometry and training. Furthermore, ultra-distance triathletes such as Triple Iron ultra-triathletes are also different compared to IRONMAN triathletes27. Obviously, ultra-endurance triathletes competing in the very long races are a highly selected population. A successful somatotype of an ultra-distance triathlete seems to be a triathlete who is smaller but heavier than an IRONMAN triathlete and with a higher body mass index, with shorter limbs and higher limb circumferences than an IRONMAN triathlete27. An ultra-triathlete seems to be smaller and more compact than an IRONMAN triathlete.

Looking at the sex difference in ultra-endurance specialists (i.e. ultra-swimmers, ultra-cyclists, ultra-runners), women can swim faster than men in open-water long-distance swimming28,29. In ultra-endurance cycling, men are faster than women30,31,32,33 where the sex differences are ~ 20% in the Race Across AMerica (RAAM) considering one of the longest ultra-cycling races in the world33. However, women were not slower than men in shorter ultra-cycling races such as 400- and 500-miles races9. In ultra-running, men were always faster than women in all ultra-marathon race distances from the shortest to the longest34,35,36. Overall, women can be faster than men in some specific ultra races in specific single disciplines, but not in races with combined disciplines such as an ultra-long triathlon race covering 30 times the full IRONMAN distance.

Variability in pacing in the split disciplines

The analysis highlighted distinct patterns in performance across cycling and running splits. Running showed a steady pacing, with consistent athletes (i.e. even pacing) performing better overall. The results emphasized how variability in pacing impacted cumulative performance and final rankings. The analysis revealed significant differences in both cycling and running times among athletes. The variability in cycling times indicated diverse pacing strategies and endurance levels, while the running times further highlighted the athletes’ individual performance dynamics. The CV highlighted performance consistency across cycling and running. Lower CV values indicated a higher consistency, which correlated with better rankings. Cycling exhibited more variability compared to running across participants. Although a regression analysis suggested a slightly negative relationship between CV and rank, the results were not statistically significant, emphasizing the need for further data to solidify these trends.

A potential explanation for the high variability in cycling could be the change in altitude. Overall, the athletes had to complete 782 cycling laps of ~ 7 km with ~ 45 m of altitude change per lap, leading to ~ 30,000 m of changes in altitude for the 5,400 cycling kilometers. In contrast, the running course was rather flat, so there was less variability in running. Little is known in the scientific literature about pacing variability in very long ultra-endurance races37. Overall, the length of a race17,38 and the performance level of the athlete17 seemed to have an influence on pacing variability. A potential explanation for the differences in pacing variability between cycling and running could be anthropometric and physiological differences between women and men22,23. Women with a lower body mass might have an advantage in climbing hills compared to men where men with a higher body mass might have in contrast an advantage in the descents of a cycling course. Regarding the physiological aspects, women with a greater fatigue resistance, a greater substrate efficiency, and a lower energetic demand might have an advantage in longer races although men have a higher muscular strength22,23.

A study investigating 969 finishers (849 men, 120 women) in 46 ultra-triathlons (e.g., Double-, Triple-, Quintuple- and Deca Iron ultra-triathlons) showed that different pacing patterns were observed by event and performance level17. In Double and Triple Iron ultra-triathlon, the faster athletes paced more evenly with less variation than moderate or slower athletes17. The variation in pacing speed increased with the length of a race17. In longer ultra-triathlon distances, such as Quintuple and Deca Iron ultra-triathlon, there was no significant difference in pacing variation between faster, moderate, and slower athletes17. A study investigating the influence of performance level and sex on pacing in a shorter (56.3 km) ultra-trail running race showed that pacing variability (CV%) was higher in high-level finishers, thus showing a greater ability to adapt their pace to the course profile than low-level finishers39. A study investigating pacing in time-limited ultra-marathons of different durations reported that finishers in the 24-hour events showed the most variable pacing40. And a study investigating pacing among the most successful runners in the 161-km Western States Endurance Run (WSER) showed that the mean CV of running speed was lower for the winners than for the other top-5 finishers and that CV of running speed was related to finish time for the 10 fastest finish times at the WSER. Overall, the fastest race times are achieved when running speed fluctuations are limited41.

Sex differences in ultra-endurance performance

Men were faster than women in all split disciplines where the sex differences were 12.4% in swimming, 24.8% in cycling and 8.5% in running. It is well-known that the men-to-women performance gap in traditional endurance sport such as marathon running remains at ~ 10%22,23. In ultra-endurance performance, the disparity has been reported as low as 4% despite the markedly lower number of women and women can even outperform men in cold-water long-distance swimming22. These specific performance differences for weight bearing and non-weight bearing exercises are most likely explained by anthropometric and physiological differences between women and men where men have a higher body mass, a higher muscle mass, a greater strength and a greater aerobic capacity and where women in turn have a greater fatigue resistance, a greater substrate efficiency, less muscle fatigability, a faster recovery and lower energetic demands22,23. Psychological aspects should, however, also be considered42,43. For example, in marathon running, women exceeded men on the motivational scales for weight concern, affiliation, psychological coping, life meaning, goal achievement and self-esteem and they scored lower on competitive motivation44,45. This might be similar in ultra-marathon running46.

Practical applications and limitations

This study offers important practical applications, such as the use of strategies that reduce performance variability, especially in cycling and running, to improve overall performance. In addition, it highlights the need for personalized training, considering the differences between segments and between sexes. The CV is indicated as a useful metric to monitor consistency and to guide race strategies. On the other hand, some limitations should be considered. One limitation is that we have not considered sleep times. Athletes participating in such a race might follow a different tactic with slower or longer rest periods, which could have a considerable impact on overall performance. External factors, such as weather conditions and nutritional strategies, were not included in the analysis. We did not consider support and nutrition, both of which have a considerable influence on ultra-endurance performance. In addition, environmental conditions such as precipitation, temperature and wind were not considered. Lap times in swimming were not recorded electronically and, therefore, unfortunately not available for analysis. The small sample size of four men and three women who finished the race within the time limit limits the generalization of the results.

Conclusion

In summary, men were faster in swimming, cycling, and running, with the sex difference being greatest in cycling. Cycling showed the greatest pacing variability, reflecting the unique endurance challenges of this segment. Running, on the other hand, exhibited steadier (even) pacing, with consistent athletes performing better overall. The results illustrate how variability in pacing affects cumulative performance and final rankings. The analysis revealed significant differences in both cycling and running times among athletes. The variability in cycling times indicates diverse pacing strategies and endurance levels, while the running times further highlight the individual performance dynamics of the athletes.

Data availability

Availability of Data and Materials For this study, we have included official results and split times from the official race website (www.ultratriathlonitaly.com/). The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Millard-Stafford, M., Swanson, A. E. & Wittbrodt, M. T. Nature versus nurture: have performance gaps between men and women reached an asymptote?? Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 13 (4), 530–535. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2017-0866 (2018). Epub 2018 May 14. PMID: 29466055.

Besson, T. et al. Sex Differences in Endurance Running. Sports Med. ;52(6):1235–1257. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-022-01651-w. Epub 2022 Feb 5. PMID: 35122632.

Tarnopolsky, M. A. Sex differences in exercise metabolism and the role of 17-beta estradiol. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 40 (4), 648–654 (2008).

Cardinale, D. A. et al. Superior intrinsic mitochondrial respiration in women than in men. Front. Physiol. 9, 1133 (2018).

Ansdell, P. et al. Physiological sex differences affect the integrative response to exercise: acute and chronic implications. Exp. Physiol. 105 (12), 2007–2021 (2020).

Beating male athletes while breastfeeding. Why do women win ultra-endurance events? (2025). https://www.givemesport.com/87978976-beating-male-athletes-while-breastfeeding-why-do-women-win-ultra-endurance-events, accessed January 5.

Le Mat, F. et al. Running Endurance in Women Compared to Men: Retrospective Analysis of Matched Real-World Big Data. Sports Med. ;53(4):917–926. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-023-01813-4. Epub 2023 Feb 21. PMID: 36802328.

Sandbakk, Ø., Solli, G. S. & Holmberg, H. C. Sex differences in World-Record performance: the influence of sport discipline and competition duration. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 13 (1), 2–8. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2017-0196 (2018). Epub 2018 Jan 2. PMID: 28488921.

Baumgartner, S., Sousa, C. V., Nikolaidis, P. T. & Knechtle, B. Can the performance gap between women and men be reduced in Ultra-Cycling? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 17 (7), 2521. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072521 (2020). PMID: 32272640; PMCID: PMC7177769.

Nikolaidis, P. T. et al. Sex difference in open-water swimming-The triple crown of open water swimming 1875–2017. PLoS One. 13 (8), e0202003. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202003 (2018). PMID: 30157202; PMCID: PMC6114520.

Knechtle, B. et al. Sex differences in swimming Disciplines-Can women outperform men in swimming? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 17 (10), 3651. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103651 (2020). PMID: 32456109; PMCID: PMC7277665.

Stevenson, J. L., Song, H. & Cooper, J. A. Age and sex differences pertaining to modes of locomotion in triathlon. Med Sci Sports Exerc. ;45(5):976 – 84. (2013). https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e31827d17eb. PMID: 23247717.

Rüst, C. A., Lepers, R., Stiefel, M., Rosemann, T. & Knechtle, B. Performance in olympic triathlon: changes in performance of elite female and male triathletes in the ITU world triathlon series from 2009 to 2012. Springerplus 2, 685. https://doi.org/10.1186/2193-1801-2-685 (2013). PMID: 24386628; PMCID: PMC3874286.

Lepers, R. Analysis of Hawaii ironman performances in elite triathletes from 1981 to 2007. Med Sci Sports Exerc. ;40(10):1828-34. (2008). https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e31817e91a4. PMID: 18799994.

Lepers, R. Sex difference in triathlon performance. Front. Physiol. 10, 973. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2019.00973 (2019). PMID: 31396109; PMCID: PMC6668549.

Rüst, C. A., Rosemann, T. & Knechtle, B. Performance and sex difference in ultra-triathlon performance from ironman to double deca iron ultra-triathlon between 1978 and 2013. Springerplus 3, 219. https://doi.org/10.1186/2193-1801-3-219 (2014). PMID: 24877030; PMCID: PMC4035499.

Stjepanovic, M. et al. Changes in pacing variation with increasing race duration in ultra-triathlon races. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 3692. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-30932-1 (2023). PMID: 36878948; PMCID: PMC9986668.

Sousa, C. V., Nikolaidis, P. T. & Knechtle, B. Ultra-triathlon-Pacing, performance trends, the role of nationality, and sex differences in finishers and non-finishers. Scand J Med Sci Sports. ;30(3):556–563. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.13598. Epub 2019 Nov 26. PMID: 31715049.

Hunter, S. K. & Senefeld, J. W. Sex differences in human performance. J Physiol. ;602(17):4129–4156. doi: 10.1113/JP284198. Epub 2024 Aug 6. PMID: 39106346 (2024).

Hunter, S. K. et al. The biological basis of sex differences in athletic performance: consensus statement for the American college of sports medicine. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 55 (12), 2328–2360 (2023). Epub 2023 Sep 28. PMID: 37772882.

Sigg, K. et al. Sex difference in double iron ultra-triathlon performance. Extrem Physiol. Med. 2 (1), 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-7648-2-12 (2013). PMID: 23849631; PMCID: PMC3710139.

Tiller, N. B. et al. Do Sex Differences in Physiology Confer a Female Advantage in Ultra-Endurance Sport? Sports Med. ;51(5):895–915. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-020-01417-2. Epub 2021 Jan 27. PMID: 33502701.

Bassett, A. J. et al. The Biology of Sex and Sport. JBJS Rev. ;8(3):e0140. (2020). https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.RVW.19.00140. PMID: 32224635.

Knechtle, B., Baumann, B., Knechtle, P., Wirth, A. & Rosemann, T. A comparison of anthropometry between ironman triathletes and ultra-swimmers. J. Hum. Kinetics. 24, 57–64 (2010).

Rüst, C. A., Knechtle, B., Knechtle, P., Wirth, A. & Rosemann, T. A comparison of anthropometric and training characteristics among recreational male Ironman triathletes and ultra-endurance cyclists. Chin J Physiol. ;55(2):114 – 24. doi: 10.4077/CJP.2012.BAA013. PMID: 22559736 (2012).

Gianoli, D. et al. Comparison between recreational male Ironman triathletes and marathon runners. Percept Mot Skills. ;115(1):283 – 99. (2012). https://doi.org/10.2466/06.25.29.PMS.115.4.283-299. PMID: 23033763.

Knechtle, B., Knechtle, P., Rüst, C. A. & Rosemann, T. A comparison of anthropometric and training characteristics of Ironman triathletes and Triple Iron ultra-triathletes. J Sports Sci. ;29(13):1373-80. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2011.587442. Epub 2011 Aug 11. PMID: 21834654 (2011).

Knechtle, B., Rosemann, T. & Rüst, C. A. Women cross the ‘catalina channel’ faster than men. Springerplus 4, 332. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-015-1086-4 (2015). PMID: 26180752; PMCID: PMC4495100.

Knechtle, B., Rosemann, T., Lepers, R. & Rüst, C. A. Women outperform men in ultradistance swimming: the Manhattan Island Marathon Swim from 1983 to 2013. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. ;9(6):913 – 24. (2014). https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2013-0375. PMID: 24584647.

Salihu, L., Rüst, C. A., Rosemann, T. & Knechtle, B. Sex Difference in Draft-Legal Ultra-Distance Events - A Comparison between Ultra-Swimming and Ultra-Cycling. Chin J Physiol. ;59(2):87–99. (2016). https://doi.org/10.4077/CJP.2016.BAE373. PMID: 27080464.

Scholz, H., Sousa, C. V., Baumgartner, S., Rosemann, T. & Knechtle, B. Changes in sex difference in Time-Limited Ultra-Cycling races from 6 hours to 24 hours. Med. (Kaunas). 57 (9), 923. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57090923 (2021). PMID: 34577846; PMCID: PMC8469116.

Rüst, C. A., Rosemann, T., Lepers, R. & Knechtle, B. Gender difference in cycling speed and age of winning performers in ultra-cycling - the 508-mile Furnace Creek from 1983 to 2012. J Sports Sci. ;33(2):198–210. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2014.934705. Epub 2014 Jul 4. PMID: 24993112 (2015).

Rüst, C. A., Knechtle, B., Rosemann, T. & Lepers, R. Men cross America faster than women–the race across America from 1982 to 2012. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 8 (6), 611–617. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.8.6.611 (2013). Epub 2013 Feb 20. PMID: 23434612.

Knechtle, B. et al. Do women reduce the gap to men in ultra-marathon running? Springerplus 5 (1), 672. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-016-2326-y (2016). PMID: 27350909; PMCID: PMC4899381.

Zingg, M. A. et al. Will women outrun men in ultra-marathon road races from 50 Km to 1,000 Km? Springerplus 3, 97. https://doi.org/10.1186/2193-1801-3-97 (2014). PMID: 24616840; PMCID: PMC3945434.

Zingg, M. A., Knechtle, B., Rosemann, T. & Rüst, C. A. Performance differences between sexes in 50-mile to 3,100-mile ultramarathons. Open. Access. J. Sports Med. 6, 7–21 (2015). PMID: 25653567; PMCID: PMC4309798.

Cuk, I., Markovic, S., Weiss, K. & Knechtle, B. Running variability in Marathon-Evaluation of the pacing variables. Med. (Kaunas). 60 (2), 218. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60020218 (2024). PMID: 38399506; PMCID: PMC10890654.

Kerhervé, H. A., Cole-Hunter, T., Wiegand, A. N. & Solomon, C. Pacing during an ultramarathon running event in hilly terrain. PeerJ 4, e2591. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.2591 (2016). PMID: 27812406; PMCID: PMC5088578.

Corbí-Santamaría, P., Herrero-Molleda, A., García-López, J., Boullosa, D. & García-Tormo, V. Variable pacing is associated with performance during the OCC® Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc® (2017–2021). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 20 (4), 3297. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043297 (2023). PMID: 36833992; PMCID: PMC9962197.

Deusch, H., Nikolaidis, P. T., Alvero-Cruz, J. R., Rosemann, T. & Knechtle, B. Pacing in Time-Limited ultramarathons from 6 to 24 Hours—The aspects of age, sex and performance level. Sustainability 13 (5), 2705. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052705 (2021).

Hoffman, M. D. Pacing by winners of a 161-km mountain ultramarathon. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. ;9(6):1054-6. (2014). https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2013-0556. Epub 2014 Mar 19. PMID: 24664982.

Méndez-Alonso, D., Prieto-Saborit, J. A., Bahamonde, J. R. & Jiménez-Arberás, E. Influence of psychological factors on the success of the Ultra-Trail runner. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 18 (5), 2704. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052704 (2021). PMID: 33800167; PMCID: PMC7967426.

Brace, A. W., George, K. & Lovell, G. P. Mental toughness and self-efficacy of elite ultra-marathon runners. PLoS One. 15 (11), e0241284. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241284 (2020). PMID: 33147236; PMCID: PMC7641431.

Nikolaidis, P. T., Chalabaev, A., Rosemann, T. & Knechtle, B. Motivation in the Athens classic marathon: the role of sex, age, and performance level in Greek recreational marathon runners. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 16 (14), 2549. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16142549 (2019). PMID: 31319497; PMCID: PMC6678471.

Waśkiewicz, Z. et al. What motivates successful marathon runners?? The role of sex, age, education, and training experience in Polish runners?. Front. Psychol. 10, 1671. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01671 (2019). PMID: 31402886; PMCID: PMC6669793.

Gerasimuk, D. et al. Age-Related differences in motivation of recreational runners, marathoners, and Ultra-Marathoners. Front. Psychol. 12, 738807. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.738807 (2021). PMID: 34803819; PMCID: PMC8604017.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Beat Knechtle collected the data and drafted the manuscript, Luciano Bernardes Leite and Pedro Forte performed the statistical analysis and drafted methods and results sections, Marilia Santos Andrade, Pantelis T. Nikolaidis, Volker Scheer, Sasa Duric, Ivan Cuk, and Thomas Rosemann helped in drafting the final version. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Knechtle, B., Leite, L.B., Forte, P. et al. Sex-specific differences in performance and pacing in the world’s longest triathlon in history. Sci Rep 15, 28688 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14578-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14578-9