Abstract

The WHO declared monkeypox a global health emergency due to its rapid spread. In response, the FDA authorized emergency use of the Jynneos vaccine despite its adverse effects, while smallpox antivirals, repurposed for monkeypox treatment, have shown limited efficacy, highlighting the need for better therapeutics that are biocompatible, less toxic, and more accessible. Tea bioactives, known for their antiviral properties, were evaluated using an in silico approach to target viral enzymes: polymerase holoenzyme and methyltransferase. A total of 68 bioactives, mainly polyphenols from tea, were analyzed through molecular docking. Among them, digalloylprocyanidin B2, TSB, and NTF showed the lowest binding energies of -9.6441 kcal mol−1, -9.1740, kcal mol−1, and − 9.1563 kcal mol−1, respectively against the polymerase holoenzyme, while TSA, TF, and TF3 exhibited the binding energies of -10.2649 kcal mol−1, -9.5998 kcal mol−1, and − 9.0857 kcal mol−1, respectively for methyltransferase. The compounds showed stronger binding than reference drugs. MDS (100 ns) using Desmond software showed that top-ranked ligand complexes were more stable than unbound proteins and reference drug complexes. MM-GBSA calculations revealed greater stability with the polymerase holoenzyme than methyltransferase. Further in vitro and in vivo studies are needed to confirm their inhibitory effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Monkeypox (MP) is a zoonotic disease caused by the monkeypox virus (MPXV), which is closely related to the variola virus that causes smallpox1. MPXV was first identified in 19582 in lesions of non-human primates and was later confirmed in humans in 19703. In May 2022, a major outbreak of MPXV began in the United Kingdom, with the first confirmed case reported on May 7 in a traveler from Nigeria4. This 2022 epidemic spread rapidly across the globe, leading to over 86,000 confirmed cases in 110 countries, including 103 countries that had no previous history of the disease1,5. In response to the escalating situation, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the monkeypox outbreak a “public health emergency of international concern” on July 23, 20226.

MPXV is an enveloped double-stranded DNA virus that belongs to the Poxviridae family, specifically the Chordopoxvirinae subfamily, Orthopoxvirus genus, and MPXV species7. The MPXV genome consists of approximately 197 kb of linear double-stranded DNA, containing around 190 non-overlapping open reading frames (ORFs) longer than 180 nucleotides2. The central coding region, spanning approximately 56,000 to 120,000 nucleotides, is highly conserved, while the variable terminal regions are made up of inverted terminal repeats (ITRs) that contribute to host-virus interactions8. The central region contains genes critical for viral entry, replication, and maturation, while the terminal regions house at least four ORFs2. Notably, despite being a DNA virus, MPXV completes its entire life cycle within the cytoplasm of infected cells. MPXV can enter host cells either by fusion with the plasma membrane or through endocytosis, with at least 16 proteins in the viral membrane playing a role in the entry process9. Following entry, the virus triggers early gene transcription, and viral DNA replication occurs at specialized perinuclear sites called viral factories10,11.

The MPXV replicative holoenzyme consists of the catalytic polymerase F8, a heterodimeric processivity factor made up of A22, and the uracil-DNA glycosylase E4. This complex plays a crucial role in the replication of the viral genome12,13,14. In parallel, MPXV must also protect itself from innate immunity. Methyltransferase is central to cap formation, allowing the virus to mask its genome and evade the host’s immune defenses, making it appear as though it originates from the host. The cap is also essential for stabilizing the mRNA. The cap formation process involves the coordinated actions of RNA-triphosphatase, RNA guanylyltransferase, and guanine-N7-methyltransferase, culminating in the generation of the Cap-0 structure15.

Polymerase holoenzyme and methyltransferase have been targeted as key therapeutic approaches for treating MP infections. Cidofovir and its derivative, brincidofovir, have been utilized to manage MP diseases, but the emergence of drug resistance due to mutations in the DNA polymerase has created significant challenges in controlling these infections16,17,18. Similarly, sinefugin has been employed as an inhibitor of methyltransferase19. In addition to these drugs, the Jynneos vaccine has been administered to control MP disease outbreaks20. Despite these interventions, both the drugs and the vaccine are associated with notable side effects, and their overall efficacy has not met expectations. Consequently, there is an urgent need to develop alternative therapeutic options that offer high biocompatibility, low toxicity, and broad accessibility to more effectively manage and contain MP outbreaks.

The development of plant-based drugs has gained significant momentum due to the rich availability and structural diversity of bioactive compounds. In this study, the tea plant (Camellia sinensis L.) was chosen as a natural candidate to explore the inhibitory potential of its bioactive constituents against key proteins of MPXV. In addition to its favorable biocompatibility, minimal toxicity, and wide availability, tea is a rich source of biologically active polyphenols, including catechins, flavonoids, anthocyanins, and phenolic acids21. These compounds are known for their extensive health benefits, including anticancer22antioxidant23anti-inflammatory24antimicrobial25anti-cardiovascular26and anti-diabetic properties27. Recent studies have demonstrated the impressive antiviral activity of tea bioactives against a variety of viruses, such as influenza, HIV, HBV, HCV, HSV, and RSV28,29,30,31. Furthermore, synergistic interactions between tea bioactives and FDA-approved antiviral drugs have been observed, especially in the treatment of RNA viruses like HCV30. Given these promising benefits, tea bioactives, particularly polyphenols, were subjected to molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations (MDS) to investigate their potential as inhibitors against two key MPXV proteins: polymerase holoenzyme and methyltransferase.

Molecular docking is a cost-effective and time-efficient method that enables rapid virtual screening of large compound libraries, predicts binding affinities with high throughput, and provides valuable insights for lead optimization. In contrast, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations offer a dynamic, time-resolved perspective on molecular interactions, capturing the flexibility and conformational changes of both proteins and ligands. By exploring the stability, dynamics, and behavior of molecules over time and under various environmental conditions, MD simulations provide a deeper understanding of molecular interactions. Together, these complementary techniques were strategically applied to identify the most potent inhibitors among tea bioactives against the target proteins of MPXV, offering a robust approach for effective drug discovery.

Methodology

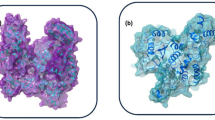

Preparation of proteins

Crystal structures of two monkeypox virus proteins methyltransferase VP39 (PDB ID: 8CEV)32 and polymerase holoenzyme (PDB ID: 8HG1)33 at resolution of 2.14 Å and 2.80 Å, respectively were selected and retrieved from the proteins data bank (https://www.rcbs.org). Both proteins were prepared using MOE software34. Initially, water molecules and attached ligands were removed using the MOE SEQ window. Missing amino acid residues were identified and repaired using Modeler software35. Any remaining structural deficiencies were corrected through the MOE structural preparation window. The 3D structures were protonated and partial charges were assigned using the Gasteiger (PEOE) forcefield. The energy of both proteins was minimized using the Amber14 forcefield specifically designed for amino acids and proteins. Active sites in both proteins were identified by applying the site finder tool embedded in MOE software. After preparation, both proteins were obtained in a ready-to-dock format.

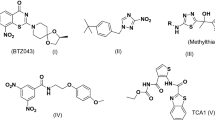

Preparation of ligands database

A total of 68 tea bioactive compounds, known for their antiviral and medicinal properties, were selected for this study36,37. In addition, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved methyltransferase inhibitors such as decitabine, clofarabine, and 5-azacitidine along with polymerase holoenzyme medications namely, cidofovir and brincidofovir were selected as reference compounds. The 3D SDF files for these compounds were obtained from PubChem (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). For compounds not available in the database, their structures were drawn using ChemDraw software (https://resources.perkinelmer.com/lab-solutions/resources/docs/app_chemdraw.html). The prepared database was processed using MOE software. All structures were prepared by assigning partial charges and adding missing protons. Subsequently, all compounds were also subjected to energy minimization and optimization using MOE software. Finally, all prepared structures were converted to.mol format and integrated into the MOE database.

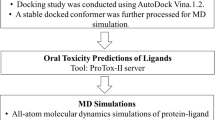

Molecular docking study

Molecular docking of tea bioactives against the target proteins was performed using MOE Dock. The active sites within the protein structures were accurately identified, and dummy atoms were strategically placed to represent the binding sites. The identified active sites of both proteins are provided in the supporting materials. During molecular docking, specific parameters were carefully set: Re-scoring function: London dG, Placement: Triangle Matcher, Retain: 30, Refinement: Force Field, and Re-scoring 2: London dG38,39. The docking process was conducted under the assumption of a rigid receptor, with the protein structure held fixed throughout the docking procedure. To analyze the binding modes and interactions, thirty poses for each ligand were selected using the London dG function40. Docking results were evaluated based on negative S scores, which indicate favorable binding affinities, and low root mean square deviation (RMSD) values. The 2D and 3D structures of the protein-ligand complexes with the lowest S scores were saved and analyzed to characterize the specific nature of the interactions.

Molecular dynamics simulation study

To gain a deeper understanding of the mechanistic insights and validate the docking results, the structures of protein-ligand complexes involving the top-ranked ligands (polymerase holoenzyme-digalloylprocyanidin B2, polymerase holoenzyme-TSB, polymerase holoenzyme-NTF, methyltransferase-TSA, methyltransferase-TF, and methyltransferase-TF3) were subjected to 100 ns MDS using Desmond software developed by Schrödinger LLC41. Each protein-ligand complex was solvated individually using the TIP3P water model, and the OPLS 2005 force field42,43 was applied to model both the protein and ligand. Physiological conditions, including a 0.154 M NaCl solution, were maintained at 310 K temperature and 1 atm pressure to ensure charge neutrality across the system. Energy minimization was performed for 100 ps to relax the system. Subsequent MD simulations were performed in an orthorhombic box with buffer dimensions of 10 Å × 10 Å × 10 Å, employing an NPT ensemble44 at 300 K and 1 atm pressure for 100 ns. The simulation was conducted in steps of 50 ps. To maintain the system’s temperature and pressure, the Nose-Hoover thermostat45 and Martyna-Tobias-Klein barostat46 were utilized, respectively. The Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method was employed to compute long-range electrostatic interactions with a grid spacing of 0.8 Å. Detailed interactions between the ligands and proteins were analyzed using the Simulation Interaction Diagram tool in the Desmond package. The results were further examined based on key parameters such as RMSD and root mean square fluctuation (RMSF), protein-ligand contacts, 2D summaries of protein-ligand interactions, and ligand property trajectories.

MM-GBSA calculations

To acquire an in-depth understanding of the molecular interactions between the proteins and ligands, binding free energies (Gbind) were calculated using the MM/GBSA (Molecular Mechanics/Generalized Born Surface Area) approach, facilitated by the thermal_mmgbsa.py Python script from Schrödinger. The VSGB solvent model47OPLS 2005 force field42,43and rotamer search algorithm48 were applied to precisely estimate the binding free energies. These calculations were performed using data from the last 20 ns of the MD production run, sampled at 100 ps intervals. The production run was carried out at a constant temperature of 300 K and pressure of 1 atm throughout all intervals. The total free energy binding was calculated using the following equation:

Where dGbind = binding free energy, dGcomplex = free energy of the complex, dGprotein = free energy of the target protein, and dGligand = free energy of the ligand.

Results and discussion

Molecular docking analyses

Molecular docking is a computational technique used to analyze the complex structures formed by the interactions between two or more molecules. Its main purpose is to predict the 3D conformation of a ligand within the binding site of the target molecule. The docking results for 68 bioactive compounds from tea, evaluated against the polymerase holoenzyme and MTase, are presented and discussed in detail as follows:

Interactions analysis with polymerase holoenzyme

Docking results indicate that all bioactives interacted with the polymerase holoenzyme. Based on binding energy, the three top-ranked compounds—digalloylprocyanidin B, NTF, and TSB—demonstrated binding energies of −9.6441 kcal mol−1, −9.1740 kcal mol−1, and − 9.1563 kcal mol−1, respectively. Seven compounds, including digalloylprocyanidin B, NTF, TSB, TF3, TF, TSA, rutin, TSF, TF2b, and procyanidin, exhibited binding energies lower than that of the reference drug brincidofovir, which showed a binding energy of −8.2497 kcal mol−1. The binding energies of the bioactives to the reference drug are provided in Table 1 and their graphical representation is shown in Fig. 1.

The interaction analysis of the three top-ranked ligands with the polymerase holoenzyme is provided in Table 2, and their graphical representation is shown in Fig. 2. These interactions are discussed below:

Digalloylprocyanidin B2 demonstrated the strongest interactions (thirteen) with the active site of the target protein. These included seven hydrogen bonds: two with Asn665 and one each with Tyr806, Tyr658, Lys661, Ser552, and Asn55; a carbon-hydrogen bond with Ser552; three pi-anion interactions with Glu792, Glu790, and Asp753; and two pi-cation bonds with Lys661 and Arg634. TSB, the second most potent bioactive compound, formed a total of fifteen interactions. These interactions included nine hydrogen bonds, with each catalytic residue—Asn551, Leu553, Asp753, Lys661, Ser754, and Tyr806—forming one hydrogen bond, while Asp549 formed two hydrogen bonds. Asn551 also formed a carbon-hydrogen bond. Asp753 and Asp549 established three and one pi-anion bonds, respectively, while Arg634 and Lys661 each formed one pi-cation bond. NTF, another tea bioactive, formed thirteen interactions with the target protein. These included six hydrogen bonds: two with Arg634 and one each with Ser552, Lys661, Ser754, and Asp751; three pi-anion bonds, two with Asp753 and one with Asp549; and two pi-cation bonds with Lys661. Additionally, two pi-donor hydrogen bonds with Asn665 and Thr752 were observed.

The F8 polymerase consists of five domains: the N-terminal, exonuclease, palm, finger, and thumb domains. The active site of the polymerase holoenzyme is formed by several key residues, including Arg634, Lys661, Ile662, and Asn665 from the finger domain, as well as Asp549, Tyr550, Asn551, Asp753, and Tyr806 from the palm domain49. The finger domain undergoes a conformational rotation of approximately 17º, positioning the positively charged residues Arg634 and Lys661 close to the active site, where they facilitate interactions with deoxythymidine triphosphate (dTTP)33.

The docking results reveal that the three top-ranked ligands form significant interactions with key catalytic residues, including Arg634, Lys661, and Asn665, within the finger domain. Digalloylprocyanidin B2 interacts with these catalytic residues—Asn665, Lys661, and Arg634—via hydrogen bonds and pi-cation interactions. Similarly, TSB forms hydrogen bonds and pi-cation interactions with Lys661 and Arg634. NTF establishes hydrogen bonds with Arg634. The finger domain, which facilitates the movement of the DNA template and primer during replication, may be disrupted by the interaction of its critical catalytic residues with the top-ranked ligands.

Similarly, substantial interactions were observed between the three top-ranked ligands and residues Asp549, Asn551, Ser552, Leu553, Asp751, Thr752, Asp753, Ser754, Glu790, Glu792, Tyr795, and Tyr806 within the palm domain. Digalloylprocyanidin B2 interacts with residues Asn551, Ser552, Asp753, Glu790, Glu792, and Tyr806 through hydrogen bonds, a carbon-hydrogen bond, and pi-anion interactions. In a similar manner, TSB forms hydrogen bonds, pi-anion, and pi-cation interactions with catalytic residues Asp549, Asn551, Leu553, Asp753, Ser754, Tyr795, and Tyr806. NTF forms hydrogen bonds and pi-anion interactions with amino acids such as Asp549, Ser552, Asp751, Thr752, Asp753, and Ser754. Notably, the aspartate residues Asp549 and Asp753 in the palm domain are particularly crucial, as they play a key role in facilitating the entry of the incoming dTTP triphosphate tail. However, the interactions between these residues and the top ligands could potentially hinder this essential step.

Interactions analysis with methyltransferase

Interaction analyses indicate that all bioactive compounds interacted with methyltransferase. Based on binding energy, the top three compounds—TSA, TF, and TF3—demonstrated binding energies of −10.2649 kcal mol−1, −9.5998 kcal mol−1, and − 9.0857 kcal mol−1, respectively. Ten compounds, including TSA, TF, TF3, TF2, TSF, TF2b, rutin, digalloylprocyanidin B, TSB, and epitheaflagallin 3-O-gallate, exhibited binding energies lower than − 8.0000 kcal mol−1. Table 3 presents the binding energies of the bioactives compared to the reference drug, with their graphical representation displayed in Fig. 3.

The interaction details of the three top-ranked ligands with the methyltransferase are summarized in Table 4, while their graphical representation is illustrated in Fig. 4. A detailed discussion of these interactions is provided below:

TSA exhibited the lowest binding energy among the analyzed compounds, forming 13 interactions with the target protein. Specifically, it established seven hydrogen bonds with the residues Tyr22, Tyr36, Gln39, Gly68, Glu147, and Ser205. In addition, six carbon-hydrogen bonds were observed with Gly38, Lys41, Arg143, and Arg177. Similarly, TF displayed ten interactions with the methyltransferase protein, including seven hydrogen bonds with residues Glu25, Gly38, Gln39, Glu147, Ala206, and Arg143. Furthermore, three carbon-hydrogen bonds were documented with residues Pro71, Pro202, and Ser205. Likewise, TF3 formed twelve interactions with the target protein, of which six were hydrogen bonds with Glu25, Leu34, Tyr36, Arg143, Glu147, and Lys175. Additionally, six carbon-hydrogen bonds were formed with Gly38, Lys41, Arg177, and Pro202.

The methyltransferase structure showcases a mixed α/β fold featuring a central β-sheet formed by β2-β10 strands that adopt a distinctive J-like shape. Stabilization of this central sheet involves interactions with helices α1, α2, α6, and α7 on one side, while α3 and α7 contribute from the other side. Bridging these opposing sides are α5, β1, and β11. The methyltransferase S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) binding pocket has two ends: one borders the RNA binding pocket and serves to place SAM for the methyltransferase activity. The opposite end is unoccupied holding a network of water molecules bonded together by H-bonds32.

TSA forms hydrogen bonds and carbon-hydrogen bonds with Gly38, Gln39, and Lys41 of the α1-helix. In addition, a hydrogen bond is formed with Glu147 in the α2-helix, while a carbon-hydrogen bond is established with Arg177 in the α4-helix and another carbon-hydrogen bond with Arg143 in the β6-sheet. Furthermore, TSA interacts with multiple sidechain residues, including Tyr22, Tyr36, Gly68, and Ser205, through hydrogen bonds. Similarly, TF forms a hydrogen bond with Gly38 and Gln39 in the α1-helix, a hydrogen bond with Glu147 in the α2-helix, and a hydrogen bond with Arg143 in the β6-sheet. Additionally, TF establishes both hydrogen bonds and carbon-hydrogen interactions with the sidechain residues Glu25, Pro71, Pro202, Ser205, and Ala206. Similarly, TF3 forms carbon-hydrogen bonds with Gly38 and Lys41 in the α1-helix, a hydrogen bond with Glu147 in the α2-helix, as well as both hydrogen bonds and carbon-hydrogen bonds with Lys175 and Arg177 in the α4-helix. Additionally, TF3 establishes a hydrogen bond with Arg143 in the β6-sheet. It also generates hydrogen bonds and a carbon-hydrogen bond with the sidechain residues Glu25, Leu34, Tyr36, and Pro202. Our top ligands demonstrate particular interactions with these residues surrounding the methyltransferase SAM binding pocket inhibiting the methyltransferase reaction. Additionally, our top ligands occupied the RNA binding pocket limiting the formation of the RNA cap which is crucial for innate immunity because innate immunity sensors are capable of identifying uncapped RNA50.

Molecular dynamics simulation analysis

The docking results were validated by subjecting both bound proteins (protein-ligand complexes of the three top-ranked ligands and reference drugs) and unbound proteins to 100 ns MDS. The trajectories were recorded and are explained as follows:

RMSD analysis of top complexes of polymerase holoenzyme

The RMSD plots for the bound proteins (protein-ligand complexes of the three top-ranked ligands) of polymerase holoenzyme are shown in Fig. 5.

The RMSD plot for the polymerase holoenzyme-digalloylprocyanidin B2 complex exhibited mean deviations of the Cα atoms below 3.5 Å. Initial fluctuations were observed up to 10 ns, after which the protein reached stability at 45 ns, maintaining equilibrium with an average RMSD of 2.3 Å. Between 45 ns and 60 ns, the RMSD showed fluctuations in the range of 2.5 to 3.5 Å. After 60 ns, the RMSD curve achieved stable equilibrium, with an average value of 3.2 Å.

Similarly, during the first 40 ns, the ligand RMSD curve exhibited significant fluctuations, suggesting that the ligand temporarily dissociated from the protein’s active site. From 40 ns to 58 ns, the RMSD curve stabilized with an average value of 2.4 Å, indicating re-binding of the ligand to the active pocket. Subsequently, the RMSD fluctuated between 2.4 and 3.8 Å, with an average value of 3.4 Å till the end of the simulation.

In the case of polymerase holoenzyme-TSB complex, Cα atoms exhibited mean deviations below 4.0 Å except for a brief period from 70 ns to 90 ns when fluctuations exceeded 4.0 Å. Between 20 ns to 42 ns, the protein RMSD curve stabilized with an average value of 2.4 Å, inferring the formation of a stable protein-ligand complex. Subsequently, the curve showed fluctuations ranging from 2.6 Å to 4.5 Å till the end of the simulation. During the first 22 ns, the ligand RMSD curve stabilized with an average value of 1.8 Å, indicating the binding of the ligand to the protein’s active site. From 23 ns to 100 ns, the ligand RMSD exhibited significant fluctuations, ranging from 2.0 to 4.5 Å.

The RMSD analysis of the polymerase holoenzyme-NTF complex showed mean deviations of the Cα atoms below 3.0 Å. During the first 25 ns, the protein RMSD curve fluctuated between 2.2 Å and 3.6 Å. From 26 ns to 100 ns, the protein RMSD curve exhibited significant equilibration, stabilizing with an average value of 2.7 Å, indicating the stability of the protein-ligand complex. Similarly, the ligand RMSD curve fluctuated for the first 30 ns, after which it reached equilibrium with an average RMSD of 2.7 Å, suggesting the binding of the ligand to the protein’s active site.

To further investigate the stability of the protein-ligand complexes formed by the three top-ranked ligands, their RMSD trajectories were compared with those of both the unbound polymerase holoenzyme and the polymerase holoenzyme-brincidofovir complex of the reference drug brincidofovir. The RMSD trajectory of the unbound polymerase holoenzyme showed that the unbound protein remained stable within the range of 1.8–2.6 Å up to 40 ns. A significant rise in the RMSD (up to 5 Å) was observed between 40 ns and 60 ns, after which the unbound protein regained equilibrium within the range of 3.0-3.6 Å for the remainder of the simulation (Figure S1).

Similarly, for the first 30 ns, the RMSD curve of the polymerase holoenzyme-brincidofovir complex fluctuated between 2.0 Å and 4.5 Å. Between 41 ns and 100 ns, the RMSD stabilized, averaging 4.2 Å (Figure S1). A comparison of the RMSD trajectory of the unbound polymerase holoenzyme with those of the complexes formed by the top-ranked ligands reveals the absence of the large peak (5 Å) in the unbound protein trajectory upon binding with all three ligands, indicating enhanced stability of the complexes. Moreover, small deviations of less than 3.0 Å were consistently observed throughout the 100 ns simulation for the top-ranked ligand complexes, while the reference drug complex exhibited larger deviations of 4.2 Å, further suggesting that the complexes with the three top-ranked ligands are more stable than the polymerase holoenzyme-brincidofovir complex.

RMSD analysis of top complexes of methyltransferase

The RMSD graphs of bound proteins (protein-ligand complexes of the three top-ranked ligands) of MTase are presented in Fig. 5.

For the methyltransferase-TSA complex, the RMSD plot displayed fluctuations in both the protein and ligand. The Cα atoms of the methyltransferase-TSA complex showed a mean deviation of less than 4.0 Å. The protein reached equilibrium after 15 ns, stabilizing within a range of 3.0–4.0 Å, with an average RMSD of 3.5 Å. The ligand RMSD curve similarly stabilized within the 3.0–4.0 Å range over the 100 ns simulation, maintaining an average RMSD of 3.5 Å.

Similarly, the RMSD plot for the methyltransferase-TF complex revealed that the Cα atoms exhibited mean deviations of less than 2.9 Å. The protein RMSD showed fluctuations during the initial 25 ns, ranging between 1.9 and 3.0 Å, before stabilizing with an average RMSD of 2.7 Å. This stable phase was maintained throughout the 100 ns simulation. The ligand RMSD remained consistent from 5 ns to 25 ns, with an average RMSD of 1.8 Å. After 25 ns, the ligand RMSD stabilized within a range, maintaining an average value of 2.7 Å. The RMSD plot indicates that both the protein and ligand reached equilibrium below 3.0 Å after 25 ns, suggesting the formation of a stable protein-ligand complex.

Similarly, the RMSD plot for the methyltransferase-TF3 complex demonstrated that the Cα atoms in the MTase-TF3A complex exhibited a mean deviation of less than 3.0 Å. The plot showed minor fluctuations during the initial 20 ns, after which the RMSD stabilized with an average value of 2.7 Å for the remainder of the simulation. The ligand RMSD remained stable at 1.8 Å between 5 ns and 28 ns, followed by a brief fluctuation at 28 ns. After this fluctuation, the ligand RMSD stabilized within the 1.8-3.0 Å range, maintaining an average RMSD of 2.7 Å. These results suggest that the methyltransferase-TF3A complex remained stable throughout the simulation period.

To further assess the stability of the protein-ligand complexes of the three top-ranked ligands, both the unbound protein (methyltransferase) and the protein-ligand complex (methyltransferase-clofarabine) of the reference drug clofarabine were subjected to 100 ns MDS. During the initial 10 ns, fluctuations were observed in the RMSD plot of the unbound protein, ranging from 2.5 to 3.8 Å. Following this, the curve stabilized, with an average RMSD of 3.5 Å with minor fluctuations till the end of the simulation (Figure S1). Similarly, the RMSD plot for the methyltransferase-clofarabine complex showed fluctuations between 2.0 Å and 3.5 Å during the first 10 ns, after which it reached equilibrium, maintaining an average RMSD of 3.5 Å with minor fluctuations observed at various intervals (Figure S1).

The methyltransferase-TF and methyltransferase-TF3 complexes exhibit greater stability than the unbound protein and the methyltransferase-clofarabine complex, as both of the former achieve equilibrium at a lower RMSD value of 2.7 Å, whereas the unbound protein and methyltransferase-clofarabine complex stabilize at a higher RMSD value of 3.5 Å. Similarly, the stability of the methyltransferase-TSA complex is comparable to that of the unbound protein and methyltransferase-clofarabine complex, as all three reach equilibrium at an RMSD value of 3.5 Å. In conclusion, all three complexes demonstrate stability throughout the 100 ns simulation. However, the methyltransferase-TF and methyltransferase-TF3 complexes exhibit superior stability, as indicated by their smaller deviations, which remain below 3.0 Å, in contrast to the methyltransferase-TSA complex.

RMSF of top complexes of polymerase holoenzyme

RMSF analysis offers valuable insights into the residue-specific stability of proteins during molecular dynamics simulations (MDS). In this study, the polymerase holoenzyme complexes with three ligands—digalloylprocyanidin B2, TSB, and NTF—showed varying degrees of fluctuation in their RMSF values. Figure 6 presents the RMSF plots for the polymerase holoenzyme complexes with the three top-ranked ligands.

In the polymerase holoenzyme-digalloylprocyanidin B2 complex, RMSF values exhibited fluctuations across different residue ranges. From the first residue to residue 650, RMSF remained between 0.8 and 2.4 Å, with a significant peak observed at residues 310–340, reaching up to 4.0 Å. Beyond residue 650 to 1006, RMSF values stayed within the 0.8-4.0 Å range. Residues interacting with the ligand were marked by green vertical bars. Notably, the majority of active site residues—such as Asn551, Ser552, Arg634, Tyr658, Lys661, Asn665, Gly669, Asp751, Asp753, Lys804, and Tyr806, which were in contact with digalloylprocyanidin B2—showed RMSF values within the 0.8-2.0 Å range.

In the polymerase holoenzyme-TSB complex, RMSF values ranged from 0.8 to 3.2 Å for most residues, with occasional fluctuations reaching up to 5.6 Å between residues 310 and 340. Residues interacting with the ligand were indicated by green vertical bars. Active site residues, including Asn549, Asn551, Ser553, Arg634, Asp654, Tyr658, Lys661, Asp751, Asp753, Ser754, Glu792, Tyr795, Tyr806, Asn825, and Lys826, generally exhibited lower RMSF values, typically ranging from 0.8 to 1.8 Å.

For the polymerase holoenzyme-NTF complex, RMSF values exhibited minimal fluctuations, remaining mostly within the 0.6-3.0 Å range. However, some fluctuations were observed between residues 300–330 and 900–920, where RMSF values reached up to 4.8 Å. Active site residues, including Gly530, Asp549, Ser552, Lys661, Asn665, Asp751, Thr752, Asp753, and Ser754, showed consistent RMSF values, typically ranging from 0.6 to 1.8 Å, as indicated by the green vertical bars representing the protein residues involved in ligand interactions. Overall, the RMSF analysis suggests that the active site residues, marked by the green bars, exhibit minimal fluctuations, indicating the formation of stable protein-ligand complexes.

RMSF of top complexes of methyltransferase

Figure 6 displays the RMSF plots for the methyltransferase complexes with the three highest-ranked ligands. In the methyltransferase-TSA complex, the RMSF analysis reveals varying degrees of flexibility across different regions. For the first 140 residues, the RMSF values remained relatively low, ranging from 0.5 to 2.5 Å, indicating minimal fluctuation and structural stability. However, residues between 140 and 150 and 210–220 exhibited larger fluctuations, with RMSF values increasing to between 0.5 and 3.7 Å, suggesting increased flexibility in these regions. Beyond these fluctuations, the remaining residues displayed a stable range of 0.5 to 1.8 Å. Residues interacting with the ligand were highlighted with green vertical bars, and these residues—such as Glu25, Ser26, Ala27, Asn28, Glu29, and Lys32—showed fluctuations exceeding 2.0 Å. Meanwhile, the catalytic residues, including Glu119, Ser203, Tyr204, Arg244, Asn245, Glu257, and Asp259, exhibited slight fluctuations with RMSF values around 1.8 Å, indicating moderate flexibility while maintaining functional stability.

In the methyltransferase-TF complex, the RMSF values showed generally low fluctuations. Most residues had RMSF values within the range of 0.5 to 3.0 Å, indicating that they remained relatively stable during the simulation. However, residues 1–25 exhibited slightly higher fluctuations, with RMSF values ranging from 0.5 to 4.2 Å, suggesting a moderate degree of flexibility in this region. Specific amino acids, including Glu25, Lys32, Lys33, Leu34, Gln37, Gly38, Gln39, Arg143, and Glu147, showed RMSF values between 3.0 and 4.5 Å. These residues exhibit higher fluctuations, suggesting that they have weaker interactions with the ligand and are less structurally stable. In contrast, residues such as Ala70, Pro202, Ser203, Ser205, Ala206, and Asp259 displayed lower fluctuations of around 1.2 Å, indicating strong and stable interactions with the ligand.

In the methyltransferase-TF3 complex, the RMSF values showed fluctuations in the range of 0.6 to 3.7 Å for residues 10–30. After this region, the RMSF values remained relatively stable, ranging from 0.5 to 2.0 Å up to residue 300, with slight increases in fluctuation (0.5 to 3.0 Å) observed between residues 140–150. Specific residues, including Glu25, Glu29, Lys32, and Leu34, exhibited RMSF values above the 3.0 Å, indicating higher fluctuations. These residues likely experience weaker interactions with the ligand and are less stable within the complex. In contrast, residues such as Pro202, Ser203, Asn240, Arg244, Asn245, Glu257, and Asp259 displayed lower RMSF values around 1.5 Å, suggesting they are more rigid and engaged in strong, stable interactions with the ligand.

Protein-ligand contacts in polymerase holoenzyme complexes

To gain a comprehensive understanding of the stability of the protein-ligand complexes, a detailed analysis of four key interaction types—hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic interactions, ionic bonds, and water bridges—was conducted. This analysis was supported by ligand-receptor histograms and stacked bar charts, which were used to normalize the interaction frequencies over the entire simulation trajectory.

In the interaction analysis of the polymerase holoenzyme-digalloylprocyanidin B2 complex (Fig. 7a), digalloylprocyanidin B2 was found to establish H-bonds with several residues in the polymerase holoenzyme including Asn665, Thr668, Gly669, Asp751, Asp753, Thr752, Lys804 and Lys826. Additionally, hydrophobic interactions were observed involving Tyr528, Tyr554, Lys661, Leu670, Lys804, and Kys826. The formation of water bridges was also noted in conjunction with hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic contacts. Ionic bonds were observed with Tyr658, Lys661, Tyr668, and Lys804. Notably, specific residues such as Lys804, Asp751, and Asn665 exhibited an interaction fraction value of 1.0, indicating their engagement in interactions throughout 100 ns simulation, whereas Gly669, Asp753, and Lys826 had an interaction fraction value of 0.50.

The interaction histogram comprises two panels: the top panel illustrates the total explicit contacts between the ligand and protein, while the bottom panel outlines the individual residues contributing to these contacts, represented by a dark orange line (Figure S2). Approximately, 12 contacts were reported for polymerase holoenzyme-digalloylprocyanidin B2 complex over 100 ns MDS, as shown in the top panel. Residues such as Asp751, Asn665, Asp753, and Lys804, indicated by darker orange lines, were involved in more than one specific contact with digalloylprocyanidin B2. Furthermore, Asp751 was found to engage in hydrogen bonding interactions for 59% of the simulation duration, whereas Asn665, Thr752, and Lys804 contributed to hydrogen bonding at rates of 20%, 22%, and 26%, respectively. Asp753 was involved in water bridge interactions for approximately 22% of the simulation time (Figure S3). Protein-ligand contacts results display that digalloylprocyanidin B2 formed H-bond with the catalytic key residue Asn665 from the finger domain, and Asp753 from the palm domain. The ligand remained bound to Asn665 and Asp753 for 100 ns and 50 ns of the MDS, respectively. Similarly, these key residues, Asn665 and Asp753, were also involved in more than one contact with the ligand. These findings support the docking results and provide insight into the potential interactions of the ligand with the specific catalytic residues of the protein over the 100 ns MDS.

In the polymerase holoenzyme-TSB complex, a complex network of interactions was elucidated, highlighting key interactions that significantly influence the molecular stability and dynamics of the system. H-bonds were established by the following residues: Glu339, Lys340, Asp654, Asn665, Asp753, Glu792, Tyr806, and Asn825. Additionally, hydrophobic interactions were observed involving Lys340, Tyr658, Lys661, and Lys826. Water bridges were detected in conjunction with hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic contacts. Ionic contacts were also noted with Lys340, Arg634, and Asn665. Notably, residues such as Lys340, Asp654, Tyr658, Lys661, Asp753, Glu792, Asn825, and Lys826 exhibited an interaction fraction value exceeding 1.0, indicating their involvement in complex formation during 100 ns MDS (Fig. 7b). Nearly, 18 contacts were documented for polymerase holoenzyme-TSB complex during the simulation period, as shown in the top panel (Figure S4). The bottom panel indicates that residues such as Lys340, Asp654, Tyr658, Asp753, Glu792, Tyr806, Asn825, and Lys826, marked with darker orange bands, exhibited more than one specific contact with TSB (Figure S3).

Further examination of specific interaction patterns reveal that Glu339, Lys826, Lys340, Tyr658, Asp654, Lys661, Glu792, Asp751, and Ser552 formed H-bonds with TSB, contributing 47%, 80%, 20%, 51%, 57%, 24%, 43%, 21% and 20%, respectively. Additionally, Ser338, Asp753, and Asp654 were involved in hydrogen bonding and contributed 21%, 28%, and 20%, respectively, while interacting with water molecules (Figure S5).

The protein-ligand contact results show that the ligand interacted with catalytic residues of both domains: finger domain (Arg634, Lys661, and Asn665) and the palm domain (Asp753 and Tyr806). Asp753 formed more than one contact with the ligand. Lys661 and Asp753 remained in contact with the ligand throughout the simulation time. These findings provide a mechanistic insight into the interaction pattern of ligand with the important catalytic residues of the active site of the protein.

For the polymerase holoenzyme-NTF complex, the interaction histogram reveals several interaction types. H-bonds were formed by residues such as Asn665, Asp753, Gly530, Lys661, Tyr658, and Tyr668, signifying their active participation in stabilizing the protein-ligand interactions. Furthermore, hydrophobic interactions were observed with residues Tyr554, Tyr668, and Lys826, contributing to the binding interface. Water bridges were identified in conjunction with H-bonds and hydrophobic contacts, with residues Asp751, Thr752, Asp549, and Arg634, enhancing the complexity of the interaction network. An interaction fraction value of 01 was recorded for Asn665, whereas Asp753, Tyr668, and Gly530 maintained an interaction fraction values of 0.8, demonstrating their consistent contacts with NTF during the simulation (Fig. 7c). The upper panel of the interaction timeline histogram highlighted specific contacts with residues Asn665, Tyr668, Asp753, and Gly530, which are prominently represented by a dark orange shade, underscoring their significant involvement (Figure S6).

A detailed analysis of hydrogen bonding patterns reveals that Asp753 formed hydrogen bonds for approximately 70% of the simulation time, whereas Gly330 contributed to hydrogen bonding interactions for 58% of the time. Asp751, Tyr668, and Lys661 also participated in hydrogen bonding with rates of 22%, 40%, and 20%, respectively, often involving water molecules (Figure S7). These results demonstrate that the ligand interacts with key catalytic residues, including Arg634, Lys661, Asn665, and Asp753. Residue Asn665 remained in contact with the ligand throughout the simulation time, whereas Asp753 maintained contact with ligand for 80% of the simulation period. The interactions of key residues (Arg634, Lys661, Asn665, and Asp753) play a crucial role in stabilizing the protein-ligand complex.

Protein-ligand contacts in methyltransferase complexes

In the context of the methyltransferase-TSA complex histogram (Fig. 8a), H-bonds were identified involving several residues, including Glu25, Ser26, Ala27, Asn28, Glu29, Glu119, Ser203, Arg244, Asn245, and Glu257. Furthermore, hydrophobic contacts were established with residues Ala27, Ala31, and Tyr204. Water bridges were formed concurrently with H-bonds and hydrophobic interactions. Notably, residues such as Glu25, Ser26, Ala27, Glu29, and Ala31 exhibited interaction fraction values of 1.0, indicating their consistent presence throughout the simulation.

The protein-ligand interaction histogram comprises two panels that collectively illustrate the overall interactions between the ligand and protein. The top panel (Figure S8) highlights residues such as Glu25, Glu29, Glu119, Ala27, and Asn245, which are depicted by a dark orange shade, underscoring their robust interactions with the ligand over the entire simulation time. Additionally, residues Glu119, Glu29, Glu25, Ser26, Tyr204 and Ala31 contributed to hydrogen bonding interactions at rates of 33%, 34%, 94%, 23%, 35%, and 29%, respectively (Figure S9). Protein-ligand contact results display that the ligand establishes various types of interactions (H-bond, hydrophobic, and water bridges) with several protein residues. These interactions are crucial for the stability of the complex, further demonstrating the significance of these residues in maintaining the integrity of the methyltransferase-TSA complex.

In the case of the methyltransferase-TF complex histogram (Fig. 8b), H-bonds were established with specific residues, including Glu29, Ala31, Lys32, Lys33, Leu34, Glu147, Tyr204, Glu207 and Asp259, demonstrating their active role in stabilizing interactions. Hydrophobic contacts were also observed with residues Val30, Lys33, Lys175, and Pro202, which contributed to the hydrophobic aspect of the protein-ligand binding interface. Moreover, water bridges were identified along with H-bonds and hydrophobic interactions, adding complexity to the interaction network. Ionic bonds were noted with residues Lys41, Arg140, Lys175, and Arg177. Notably, several residues, such as Lys32, Leu34, Glu147, and Asp259, exhibited interaction fraction values greater than 0.8, indicating their consistent participation in complex formation during the simulation time.

The top panel of the methyltransferase-TF complex timeline histogram (Figure S10) highlights specific contacts with residues such as Asp259, Glu147, Leu34, Lys32, and Lys33, depicted in dark orange shades to signify their notable interactions over the simulation trajectory. This was further supported by the bottom panel, which provides details of hydrogen bonding contributions. Asp259, Lys32, and Lys33 consistently formed H-bonds at rates of 53%, 69%, and 23%, respectively, throughout the simulation. Additionally, Glu147 participated in H-bond interaction, accounting for 25% of these interactions, often involving water molecules (Figure S11). These results show that the ligand forms H-bond and hydrophobic interactions with Glu147 from α2 region and Lys175 from α4 region. Catalytic residues, Glu147 and Lys175 along with other important residues such as Glu29, Val30, Ala31, Lys32, Lys33, Leu34, Lys41, Arg140, Lys175, Arg177, Pro202, Tyr204, Glu207, and Asp259, interact with the ligand, contributing to the complex stability.

The methyltransferase-TF3 interaction histogram (Fig. 8c) reveals a variety of interaction types that contribute to the stability of the complex. Key residues, including Glu25, Ala31, Lys32, Gln37, Glu257, and Asp259, formed H-bonds, playing a crucial role in stabilizing the protein-ligand interactions. Hydrophobic interactions were facilitated by residues such as Met1, Ala31, Lys32, Arg244, and Tyr260, contributing to the hydrophobic binding interface between the protein and the ligand. Additionally, water bridges were observed alongside hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions, with Asn240 and Lys241 further enriching the interaction network. Ionic interactions were also present, particularly with residues Lys33 and Ser203. Notably, Glu25, Glu29, Lys32, Ser203, Arg244, Glu257, and Asp259 exhibited interaction fraction values of 1.0, indicating their consistent involvement in interactions with TF3 throughout the simulation, which significantly contributes to the overall stability of the complex.

The methyltransferase-TF3 interaction histogram offers valuable insights into the specific residues involved in ligand binding. The dark orange band in Figure S12 highlights key residues, including Asp259, Arg244, Lys32, Ser203, and Glu25, which exhibited strong and sustained interactions with the ligand throughout the simulation. Further analysis in Figure S13 illustrates the extent of hydrogen bonding contributions by individual residues. Met1, Glu25, Glu29, Ala31, Gln37, and Asp259 formed consistent hydrogen bonds at rates of 49%, 54%, 20%, 32%, 28%, and 72%, respectively. Additionally, Ser203, Asn240, Arg244, and Glu257 contributed to hydrogen bonding interactions at rates of 27%, 56%, 34%, and 27%, often involving water molecules. These findings demonstrate that H-bonds, hydrophobic interactions, and water bridges form critical contacts between the ligand and several catalytic residues of the protein, collectively ensuring the stability of the complex throughout the simulation.

Ligand properties of polymerase holoenzyme complexes

Figures 9, S14, and S15 illustrate the properties of digalloylprocyanidin B2, TSB, and NTF, respectively, during the 100 ns simulation.

The RMSD analysis for digalloylprocyanidin B2 shows that the ligand experienced minimal fluctuations up to 20 ns, after which it stabilized, maintaining a consistent range of 0.8–1.6 Å for the remainder of the simulation. The Radius of Gyration (rGyr) values initially ranged from 5.7 to 6.0 Å up to 30 ns, followed by some fluctuations that kept it between 5.6 and 5.9 Å until 70 ns. Beyond 70 ns, rGyr fluctuated between 5.7 and 6.1 Å. Intramolecular hydrogen bonding (Intra-HB) analysis reveals the formation of hydrogen bonds within the ligand, which were present both at the beginning and end of the simulation. The Molecular Surface Area (MolSA), calculated with a 1.4 Å probe radius, remained relatively stable in the range of 635–660 Ų throughout the simulation. Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA) showed fluctuations up to 30 ns, followed by stabilization within the range of 445–455 Ų, with only minor fluctuations until the end of the 100 ns simulation. Similarly, the Polar Surface Area (PSA) fluctuated between 660 and 680 Ų up to 50 ns, after which it stabilized within the range of 660–700 Ų from 50 ns to 100 ns.

The RMSD analysis for TSB shows that the value stabilized and remained within the range of 1.6–2.4 Å until 60 ns. Following this period, fluctuations occurred within the range of 1.5–1.7 Å from 60 ns to 70 ns, after which the RMSD stabilized again, maintaining a range of 1.8–2.4 Å from 70 ns to 100 ns. The rGyr values for TSB remained largely stable, fluctuating between 4.90 and 5.10 Å throughout the simulation, with a brief fluctuation observed between 50 ns and 65 ns. Intra-HB analysis reveals the presence of a single hydrogen bond within the ligand until 70 ns, after which no hydrogen bonds were detected. MolSA calculations showed that the ligand reached equilibration, maintaining values within the range of 550–570 Ų throughout the simulation. SASA values exhibited fluctuations between 300 and 350 Ų during the first 20 ns, followed by a broader range of 320–400 Ų until 60 ns. After 60 ns, SASA remained relatively stable, fluctuating between 250 and 350 Ų for the remainder of the simulation. PSA ranged between 600 and 630 Ų up to 30 ns, after which it stabilized within the range of 630–660 Ų for the duration of the simulation.

The RMSD analysis for NTF indicates that its value stabilized at 30 ns and remained consistently within the range of 0.5-1.0 Å, with only minor fluctuations for the remainder of the simulation. The rGyr values also stabilized at 35 ns and stayed within the range of 4.60–4.75 Å for the rest of the simulation period. Intra-HB analysis shows that a hydrogen bond persisted within the ligand throughout the entire simulation. MolSA calculations showed fluctuations until 30 ns, after which they stabilized and remained within the range of 445–450 Ų for the remainder of the 100 ns simulation. SASA values fluctuated until 30 ns, then stabilized within the range of 280–320 Ų for the duration of the simulation. PSA values were unstable up to 25 ns but then stabilized within the range of 425–435 Ų until the simulation’s conclusion. These results indicate that the top-ranked ligands—digalloylprocyanidin B2, TSB, and NTF—demonstrate stability throughout the 100 ns MD simulation.

Ligands properties of methyltransferase complexes

Figures 10, S16, and S17 depict the properties of TSA, TF, and TF3, respectively, over the course of the 100 ns simulation.

The RMSD analysis of the ligand in the methyltransferase-TSA complex shows that it reached equilibrium at around 3.0 Å, maintaining stability for most of the simulation after an initial fluctuation. The rGyr of the ligand remained within the range of 5.5–5.8 Å throughout the simulation, with minimal fluctuations. Intra-HB analysis reveals that no hydrogen bonds were formed within the ligand molecule for most of the simulation. MolSA calculations showed fluctuations, with values consistently ranging between 650 and 670 Ų throughout the entire simulation. SASA values fluctuated until 30 ns, after which they stabilized and remained between 400 and 510 Ų for the rest of the simulation. Similarly, PSA values exhibited some variation but stayed within the range of 700–750 Ų throughout the entire simulation.

The RMSD analysis of TF reveals distinct stability patterns. The RMSD value remained stable within the range of 0.6-1.0 Å until 80 ns, with a noticeable fluctuation between 35 and 45 ns, where it reached 1.0-1.4 Å. After this fluctuation, the RMSD value stabilized again at 1.8 Å. The rGyr values fluctuated between 4.95 and 5.10 Å until 80 ns, followed by further fluctuations before stabilizing in the range of 4.80–4.95 Å. Intra-HB analysis shows that H-bonds were consistently present within TF throughout the entire simulation. MolSA values remained stable between 445 and 456 Ų for the first 80 ns, after which they fluctuated within the range of 440–450 Ų for the remainder of the simulation. SASA values fluctuated throughout the simulation, initially stabilizing at 30 ns within the range of 200–300 Ų until 70 ns. Following a brief fluctuation, SASA stabilized again within the range of 140–200 Ų. PSA values showed fluctuations between 440 and 455 Ų until 80 ns, before stabilizing between 435 and 445 Ų for the remainder of the simulation.

RMSD analysis of TF3 indicates its stability within a narrow range of approximately 1.0 Å, with minor fluctuations observed between 0.9 and 1.6 Å throughout the simulation. The rGyr values showed fluctuations at two specific points, around 20 ns and 50 ns, before stabilizing within the range of 5.3–5.5 Å for the remainder of the simulation. Intra-HB analysis reveals consistent formation of H-bonds throughout most of the simulation, with an increased frequency of bond formation towards the later stages. MolSA values remained steady, fluctuating between 600 and 630 Ų throughout the entire simulation. SASA values primarily remained in the range of 240–300 Ų, with brief fluctuations observed at 40 ns and 90 ns. PSA values showed minor fluctuations, varying between 610 and 650 Ų, with a brief dip between 15 and 20 ns. Overall, this analysis provides valuable insights into the stability and dynamics of TF3 during the simulation. These results suggest that ligands like TSA, TF, and TF3 remain stable throughout the simulation period.

Estimation of binding free energy

The MM-GBSA method is frequently used to evaluate the binding energy of ligands to protein molecules51. It also establishes a significant relationship between experimental and predicted binding energies. The influence of additional non-bonded interaction energies, as well as the binding free energy of the top three complexes was evaluated. Gbind is governed by non-bonded interactions such as Gbind Coulomb, Gbind Packing, Gbind H-bond, Gbind Lipo, and Gbind vdW. The average binding energy was primarily influenced by the Gbind vdW, Gbind Lipo, and Gbind Coulomb energies across all types of interactions. MM-GBSA binding energies for proteins-ligand complexes are given in Table 5. The binding free energies for the polymerase holoenzyme-digalloylprocyanidin B2, polymerase holoenzyme-TSB, and polymerase holoenzyme-NTF complexes were recorded as −21.40 kcal mol−1, −36.96 kcal mol−1, and − 39.96 kcal mol−1, respectively. In comparison, the docking studies reported binding energies of −9.6441 kcal mol−1, −9.1740 kcal mol−1, and − 9.1563 kcal mol−1for these complexes, respectively. For the methyltransferase-TSA, methyltransferase-TF, and methyltransferase-TF3 complexes, the binding free energies were − 6.55 kcal mol−1, −16.40 kcal mol−1, and − 6.51 kcal mol−1, respectively, while the docking binding energies were − 10.2649 kcal mol−1, −9.5998 kcal mol−1, and − 9.0857 kcal mol−1, respectively. The docking results do not align with the MM-GBSA binding energies in both cases. However, based on MM-GBSA binding energies, the polymerase holoenzyme-digalloylprocyanidin B2, polymerase holoenzyme-TSB, polymerase holoenzyme-NTF complexes are considered stable complex systems. In these complexes, Van der Waals and Coulombic interactions play a major role in stabilizing the ligand-protein complex. Furthermore, digalloylprocyanidin B2, TSB, and NTF establish stable hydrogen bonds with the polymerase holoenzyme, as indicated by the dGbind H-bond interaction values.

Conclusions

In this study, tea bioactives, renowned for their potent antiviral properties, demonstrate remarkable binding affinities with the target proteins of MPXV. Among the tested bioactives, digalloylprocyanidin B2, TSB, and NTF exhibited the lowest binding energies of −9.6441 kcal mol−1, −9.1740 kcal mol−1, and − 9.1563 kcal mol−1, respectively, against the polymerase holoenzyme, showcasing their strong inhibitory potential. Similarly, TSA, TF, and TF3 displayed the highest binding affinities, with binding energies of −10.2649 kcal mol−1, −9.5998 kcal mol−1, and − 9.0857 kcal mol−1, respectively, against methyltransferase. Notably, these top-performing bioactives surpassed reference antiviral drugs in their binding affinities, highlighting their promising therapeutic potential. In contrast, MM-GBSA calculations for the polymerase holoenzyme-digalloylprocyanidin B2, polymerase holoenzyme-TSB, and polymerase holoenzyme-NTF complexes yielded binding free energies of −21.40 kcal mol−1, −36.96 kcal mol−1, and − 39.96 kcal mol−1, respectively. For the methyltransferase-TSA, methyltransferase-TF, and methyltransferase-TF3 complexes, the corresponding binding free energies were − 6.55 kcal mol−1, −16.40 kcal mol−1, and − 6.51 kcal mol−1. While the docking binding energies are not entirely aligned with the MM-GBSA results, the MM-GBSA analysis indicates that the polymerase holoenzyme forms more stable protein-ligand complexes with the top-ranked ligands compared to methyltransferase. In conclusion, these top-ranked ligands exhibit significant potential as therapeutic agents for MP infection, effectively inhibiting target proteins through the formation of stable protein-ligand complexes. In addition to their promising inhibitory effects against MPXV, these compounds exhibit excellent biocompatibility, widespread availability, and low toxicity, positioning them as more favorable alternatives to conventional antiviral drugs. To further confirm their efficacy, additional studies employing in vitro and in vivo models are strongly recommended.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and itssupplementary information files].

References

Bunge, E. M. et al. The changing epidemiology of human monkeypox—A potential threat? A systematic review. PLOS Negl. Trop. Dis. 16 (2), e0010141 (2022).

Kugelman, J. R. et al. Genomic variability of Monkeypox virus among humans, Democratic Republic of the congo. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 20 (2), 232–239 (2014).

Kumar, N., Acharya, A., Gendelman, H. E. & Byrareddy, S. N. The 2022 outbreak and the pathobiology of the Monkeypox virus. J. Autoimmun. 131, 102855 (2022).

Vivancos, R. et al. Community transmission of Monkeypox in the united kingdom, April to May 2022. Euro. Surveill. 27 (22), 2200422 (2022).

2022–2023 Mpox Outbreak Global Map. Accessed January 26, (2025). https://archive.cdc.gov/#/details?url=https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/mpox/response/2022/world-map.html

WHO Director-General declares. mpox outbreak a public health emergency of international concern, Accessed January 26, (2025). https://www.who.int/news/item/14-08-2024-who-director-general-declares-mpox-outbreak-a-public-health-emergency-of-international-concern

Moore, M. J., Rathish, B. & Zahra, F. Mpox (Monkeypox) [Updated 2023 May 3]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; Jan- (2024). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK574519/

Alkhalil, A. Inhibition of Monkeypox virus replication by RNA interference. Virol. J. 6, 1–10 (2009).

Moss, B. Membrane fusion during poxvirus entry. Semin. Cell Biol. 60, 89-96 (2016).

Greseth, M. D. & Traktman, P. The life cycle of the vaccinia virus genome. Annu. Rev. Virol. 9 (1), 239–259 (2022).

Moss, B., Poxvirus, D. N. A. & Replication Cold Spring Harb Perspect. Biol. 5, a010199 (2013).

Stanitsa, E. S., Arps, L. & Traktman, P. Vaccinia virus uracil DNA glycosylase interacts with the A20 protein to form a heterodimeric processivity factor for the viral DNA polymerase. J. Biol. Chem. 281 (6), 3439–3451 (2006).

Tarbouriech, N. et al. The vaccinia virus DNA polymerase structure provides insights into the mode of processivity factor binding. Nat. Commun. 8 (1), 1455 (2017).

Choi, W. S. et al. How a B family DNA polymerase has been evolved to copy RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 117(35), 21274–21280 (2020).

Ramanathan, A., Robb, G. B. & Chan, S-H. mRNA capping: biological functions and applications. Nucleic Acids Res. 44 (16), 7511–7526 (2016).

Smee, D. F., Sidwell, R. W., Kefauver, D., Bray, M. & Huggins, J. W. Characterization of wild-type and cidofovir-resistant strains of camelpox, cowpox, monkeypox, and vaccinia viruses. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46 (5), 1329–1335 (2002).

Baker, R. O., Bray, M. & Huggins, J. W. Potential antiviral therapeutics for smallpox, Monkeypox and other orthopoxvirus infections. Antivir Res. 57 (1–2), 13–23 (2003).

Quenelle, D. C. & Kern, E. R. Treatment of vaccinia and Cowpox virus infections in mice with CMX001 and ST-246. Viruses 2 (12), 2681–2695 (2010).

Pugh, C. S., Borchardt, R. T. & Stone, H. O. Sinefungin, a potent inhibitor of virion mRNA(guanine-7 methyltransferase, mRNA(nucleoside-20 -)methyltransferase, and viral multiplication. J. Biol. Chem. 253 (12), 4075–4077 (1978).

Kriss, J. L. et al. Receipt of First and Second Doses of JYNNEOS Vaccine for Prevention of Monkeypox - United States. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 71(43),1374-1378 (2022).

LIczbiński, P. & Bukowska, B. Tea and coffee polyphenols and their biological properties based on the latest in vitro investigations. Ind. Crops Prod. 175, 114265 (2022).

Chattopadhyay, S. et al. Tumor-shed PGE2 impairs IL2Rγc-signaling to inhibit CD4+ T cell survival: regulation by theaflavins. PLoS One, 4(10), e7382, 1-10 (2009).

Zhong, R. Z. et al. Effect of tea catechins on regulation of cell proliferation and antioxidant enzyme expression in H2O2-induced primary hepatocytes of goat in vitro. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 97 (3), 475–484 (2013).

Seong, K-J. et al. Epigallocatechin-3 gallate rescues LPS-impaired adult hippocampal neurogenesis through suppressing the TLR4-NF-jB signaling pathway in mice. Korean J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 20 (1), 41–51 (2016).

Renzetti, A., Betts, J. W., Fukumoto, K. & Rutherford, R. N. Antibacterial green tea catechins from a molecular perspective: mechanisms of action and structure–activity relationships. Food Funct. 11 (11), 9370–9396 (2020).

Li, D. et al. Effects and mechanisms of tea regulating blood pressure: evidences and promises. Nutrients 11 (5), 1115 (2019).

Liu, Z., Chen, Q., Zhang, C. & Ni, L. Comparative study of the anti-obesity and gut microbiota modulation effects of green tea phenolics and their oxidation products in high-fat-induced obese mice. Food Chem. 367, 130735 (2022).

Song, J. M., Lee, K. H. & Seong, B. L. Antiviral effect of catechins in green tea on influenza virus. Antivir Res. 68 (2), 66–74 (2005).

Liu, S. et al. Theaflavin derivatives in black tea and Catechin derivatives in green tea inhibit HIV-1 entry by targeting gp41. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1723 (1–3), 270–281 (2005).

Chowdhury, P. et al. The aflavins, polyphenols of black tea, inhibit entry of hepatitis C virus in cell culture. PLoS One. 13 (11), e0198226 (2018).

Yang, Z. F. et al. Comparison of in vitro antiviral activity of tea polyphenols against influenza A and B viruses and structure–activity relationship analysis. Fitoterapia 93, 47–53 (2014).

Silhan, J. et al. Discovery and structural characterization of Monkeypox virus methyltransferase VP39 inhibitors reveal similarities to SARS-CoV-2 nsp14 methyltransferase. Nat. Commun. 14 (1), 2259 (2023).

Peng, Q. et al. Structure of Monkeypox virus DNA polymerase holoenzyme. Science 379 (6627), 100–105 (2023).

Molecular Operating Environment (MOE). 2020.09. Chemical Computing Group ULC, 910–1010 Sherbrooke St. W., Montreal, QC H3A 2R7, Canada, (2020).

Šali, A. & Blundell, T. L. Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of Spatial restraints. J. Mol. Biol. 234 (3), 779–815 (1993).

Samanta, S. Potential bioactive components and health promotional benefits of tea (Camellia sinensis). J. Am. Nutr. Assoc. 41 (1), 65–93 (2022).

Luo, Q., Luo, L., Zhao, J., Wang, Y. & Luo, H. Biological potential and mechanisms of tea’s bioactive compounds: an updated review. J. Adv. Res. 65, 345–363 (2024).

Scholz, C., Knorr, S., Hamacher, K. & Schmidt, B. DOCKTITE-A highly versatile Step-by-Step workflow for covalent Docking and virtual screening in the molecular operating environment. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 55 (2), 398–406 (2015).

Jain, A. N. Scoring functions for protein-ligand Docking. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 7 (5), 407–420 (2006).

Desmond Molecular Dynamics System. Schrödinger Release 2020-1; D. E (Shaw Research, 2020).

Maestro-Desmond Interoperability Tools; Schrödinger: New York, (2020).

Shivakumar, D. et al. Prediction of absolute solvation free energies using molecular dynamics free energy perturbation and the OPLS force field. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 6 (5), 1509–1519 (2010).

Kaminski, G. A., Friesner, R. A., Tirado-Rives, J. & Jorgensen, W. L. Evaluation and reparametrization of the OPLS-AA force field for proteins via comparison with accurate quantum chemical calculations on peptides†. J. Phys. Chem. B. 105, 6474–6487 (2001).

Shinoda, W. & Mikami, M. Rigid-body dynamics in the isothermal-isobaric ensemble: a test on the accuracy and computational efficiency. J. Comput. Chem. 24 (8), 920–930 (2003).

Martyna, G. J., Klein, M. L. & Tuckerman, M. Nose-hoover chains- the canonical ensemble via continuous dynamics. J. Chem. Phys. 97, 2635–2643 (1992).

Martyna, G. J., Tobias, D. J. & Klein, M. L. Constant pressure molecular dynamics algorithms. J. Chem. Phys. 101, 4177–4189 (1994).

Li, J. et al. The VSGB 2.0 model: a next generation energy model for high resolution protein structure modeling. Proteins 79 (10), 2794–2812 (2011).

Gordon, D. B., Hom, G. K., Mayo, S. L. & Pierce, N. A. Exact rotamer optimization for protein design. J. Comput. Chem. 24 (2), 232–243 (2003).

Li, Y., Shen, Y., Hu, Z. & Yan, R. Structural basis for the assembly of the DNA polymerase holoenzyme from a Monkeypox virus variant. Sci. Adv. 9 (16), eadg2331 (2023).

Thoresen, D. et al. The molecular mechanism of RIG-I activation and signaling. Immunol. Rev. 304 (1), 154–168 (2021).

Godschalk, F., Genheden, S., Söderhjelm, P. & Ryde, U. Comparison of MM/GBSA calculations based on explicit and implicit solvent simulations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15 (20), 7731–7739 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Department of Chemistry, Islamia College, Peshawar, KP, Pakistan for the provision of all facilities needed to execute the project. The authors are also thankful to Universidade Federal de Pelotas—UFPel, Pelota, RS, Brazil for providing support to perform this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.M. Methodology, Literature survey, Data curation. K.K. Writing the manuscript, Conceptualization, and Supervision. A.K. Methodology, Data curation. H.U.R. Writing – review & editing, Validation, Software. A.U.J. Formal analysis, Software. T.S. Reviewing and editing of the original draft, Formal analysis. N.A. Data curation, conceptualization, software.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mumtaz, M., Khan, K., Khan, A. et al. Inhibition of monkeypox polymerase holoenzyme and methyltransferase using bioactive compounds of black tea: a computational approach. Sci Rep 15, 34639 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14583-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14583-y